CHAPTER 82 Domestic Violence

Although the term domestic violence may be broadly interpreted to include child and elder abuse, in this chapter it refers to violence that occurs in the context of an intimate relationship. Similar terms for this phenomenon include battering, partner violence, spouse abuse, and wife-beating. Domestic violence is a pattern of intentionally violent, coercive, or controlling behaviors by a current or previously intimate partner of the victim. The violence is a means toward the goal, which is to assert and to maintain power and control over the victim.1 This behavioral pattern may encompass humiliation, emotional torment, economic control, social isolation, and sexual assault, as well as threatened and actual physical injury. Because the majority of domestic violence involves male perpetrators in heterosexual relationships,2,3 this chapter will use the convention of female pronouns for victims and male pronouns for perpetrators. This is not to imply the totality of the problem, which includes male victims and female batterers, as well as violence in same-sex relationships.

There is neither societal stratum nor current or past civilization shown to be exempt from domestic violence. This endemic affliction has grave and extensive public health implications, not the least of which are the physical injury, physical and mental disability, and possible death of the abused. The societal costs of domestic violence include health care expense, lost wages, and decreased or lost productivity, as well as the generational implications of, and the long-term effects on, children who witness such violence.3–5 Studies of routine screening have shown that detection, though necessary, is not sufficient for successful intervention.6–9 Despite improved provider awareness, attitudes, stereotypes, time constraints, a sense of futility, and perceived lack of resources remain barriers to detection.10,11 Victims live with shame, fear, limited (and often highly controlled) resources, and a perpetrator-distorted sense of reality, which serve as deterrents to disclosure. The danger is real. If not handled well, disclosure and detection may seriously increase the victim’s risk: a victim who leaves has a 75% greater risk (than those who stay) of being murdered by her batterer.12

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Although controversy exists,13–16 a large national survey3 demonstrated that domestic violence in the United States affects women six times as often as men, with approximately 4.5 million annual episodes of abuse perpetrated against women by an intimate partner or a former partner. Female victims experience a mean of 3.4 assaults per year, which translates to 1.5 million American women assaulted by an intimate partner yearly, or a victimization rate of 44.2 per 1,000 women. Most (85%) episodes of domestic violence involve men who abuse their female partners. In fact, women are more likely to be assaulted, raped, or murdered by a current or previous male partner than by a stranger (72.1% versus 10.6%). While American men experience more pervasive violence, they are more likely to be assaulted by a stranger (56.2%) than by an intimate female partner or previous partner (16.6%). The difference in the rates of partner abuse experienced by women versus men escalates with the severity of violence, with women being 7 to 14 times more likely to be beaten up, choked, or threatened with a firearm or drowning. An estimated 30% to 50% of married couples experience some instance of physical violence. Although not as extensively studied, same-sex couples appear to have rates of violence similar to their heterosexual counterparts.17,18 When women are violent toward their male partners, it is often, though not always, in the setting of self-defense, and less likely to cause physical injury.3 Domestic violence has a recurrent and escalating pattern, with spousal murder accounting for approximately 1 out of 10 homicides (11%). Approximately one-third of female homicide victims are murdered by a current or former intimate partner.19

Much is known about the prevalence of abused women in various medical settings. In the emergency department (ED), 11% of women seen for any cause are in abusive relationships,20 although only 2% of women seen in the ED may seek treatment for abuse-related acute trauma.21 Among women seen emergently for non–motor vehicle trauma, the prevalence of intimate partner abuse may be as high as 40%. The lifetime prevalence of abuse in women seen in the ED may be over 50%.20 For women being seen in a general medical setting, 14% to 28% may be victims of domestic violence,22,23 while 7% to 16% of those obtaining routine prenatal care have been victimized.24–26 In the pediatric setting, more than half of the mothers of abused children are themselves being abused.27

Psychiatrists have an even greater opportunity and challenge to ascertain and to address the needs of abused women, who account for one-fourth of all women treated at emergency psychiatric services, one-third of all women who attempt suicide,28 one-half of all women in outpatient psychiatric care, and almost two-thirds of women on inpatient psychiatric units.29

RISK FACTORS FOR VICTIMS AND PERPETRATORS

Psychiatrists, as well as other health care providers, should maintain a high level of suspicion regardless of the patient’s socioeconomic, educational, professional, ethnic, racial, or religious affiliation. Domestic violence is the great equalizer; it respects no such boundaries.30

However, certain women (and couples) are at greater risk,2,31 and they deserve heightened sensitivity and scrutiny. Table 82-1 lists some of these features. Young women (in their teens and twenties), especially if single (divorced or separated) or pregnant, are more likely to be abused by a current or former partner. Filing a restraining order, especially a temporary restraining order, further increases the risk.32 This act of independence may fuel the abuser’s need to assert his domination and control. A woman may be “poor” because her abuser controls (and limits) the financial and other resources available to her. Abused women often turn to drugs or to alcohol (for an escape, and to tolerate or numb their experience of abuse). Drug or alcohol use by a woman’s partner may also increase her risk, as his irritability, irrationality, and disinhibition increase. The presence of an excessively jealous (controlling, easily angered) or possessive partner,12 especially one who seems overly involved in the woman’s medical visit, or refuses to leave the examination or interview room, should significantly raise the clinician’s level of suspicion.31

Table 82-2 lists some of the other traits found to correlate with men at increased risk of injuring their partners.33 It is not surprising that men with an antisocial personality disorder are overly represented among violent perpetrators. However, it may be less intuitive that young men, especially with limited financial means and education, are also at increased risk. Depression is also associated with increased violence in men.34

Table 82-2 Risk Factors for Violence in Male Perpetrators

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF VICTIMS

The only unifying feature of victims of domestic violence is the existence of a partner who is violent. All segments of the population are represented. No previctimization personality type has been defined or identified to predispose a person to be abused. However, the repeated abuse experience often leads to a pattern of behavior that appears character disordered. Persistent emotional badgering, physical abuse, or sexual assault may result in intense shame and an overwhelming sense of worthlessness and incompetence. When such women seek medical attention, especially when accompanied by their batterer, they often seem dependent and overly passive. They frequently do not look abused, or have injuries or obvious evidence of battering. They may have vague physical or behavioral complaints. They may be seen as “somatic” and emotionally unstable.35 (Such a woman may fare even less well in the legal arena.)

In fact, an abused woman may be entirely dependent on her abuser. Social isolation serves to cut off any outside contact or support, including, and especially, from the victim’s own family of origin or long-time friends. Humiliating economic control and deprivation further restrict her independence and increase her vulnerability. Living with chronic fear and threats may be even more detrimental than the actual physical abuse.1 While a victim may find ways to endure, dissociate, or numb the physical pain and fear, threats to her children, family, or pets5 may be continually unbearable. Even total submission may seem a reasonable price to pay to keep those she cares about safe. Such passive, dependent, and submissive behavior is the result of repeated abuse, not a predisposing condition. In fact, it is the goal, not the cause, of the abuse.1

Certain psychiatric disorders are more commonly associated with domestic violence.34,36 Drug and alcohol use and addiction disorders are more common among victims of abuse. Eating disorders are also associated with domestic violence.31 Not surprisingly, depression and anxiety are frequent co-morbidities.34 Of women seen in emergency settings, those with current or past partner abuse are more than three times as likely to have made a suicide attempt.20 Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), with the associated hyperarousal, flashbacks, and nightmares, is especially common in, though not limited to, victims who also have a childhood history of abuse.37 This syndrome may go unrecognized when the patient does not volunteer the traumatic precipitant, which underscores the need for astute pattern recognition skills. Various chronic pain syndromes (including headaches, pelvic pain, intractable abdominal pain, and musculoskeletal problems) are also associated with domestic violence.35,38,39

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF PERPETRATORS

There may be shared cultural and developmental experiences that predispose to certain personality traits, but perpetrators of domestic violence are not limited to any particular segment of society. However, just as the impact of violence shapes the pattern of victim behavior and appearance, there is an identifiable pattern of behavior, experience, and style in those who have become violent in their intimate relationships (Table 82-3).

Table 82-3 Perpetrator Patterns of Experience, Traits, and Behaviors

Perpetrator family histories frequently reveal violence in which the perpetrator was either a witness or a victim.40 The personal histories of violent men suggest a pattern of violence in previous relationships. Often young and poorly educated, batterers may be immature,2,33 dependent, and needy, with an easily shattered sense of competence, worth, and self-esteem. Perpetrators tend not to be assertive in direct and positive ways, but to feel intensely inadequate, and thus jealous and untrusting of their partners. Any suggestion of autonomy is seen as an affront and as intolerable.12 They may rely on alcohol or drugs (or both) to bolster their sense of worth or power.2,3,41–43 They may, in turn, blame such intoxication for their loss of control when violence occurs (although victims often negate this association, and suggest that the violence is independent of use or intoxication).33

In terms of disclosure and responsibility, perpetrators have a pattern of concealment, denial, and blaming.44 Socially charming and engaging, and extremely cognizant of outward appearances, the batterer often appears grounded and reliable while portraying the victim as emotionally unbalanced and exaggerating. With the victim, the perpetrator will often downplay the extent, frequency, or damage of the abuse. The perpetrator may, as mentioned, blame the effects of intoxication. A form of abuse in and of itself, the perpetrator may blame the victim for provoking or deserving the abuse.

THE NATURE OF VIOLENT RELATIONSHIPS

The recognizable pattern in the development of abusive relationships is replete with overtures of caring and exceptional thoughtfulness. The initial lack of violence or irritability offers no omen to the unaware partner. During this nonassaultive prodrome, the future perpetrator may be inordinately attentive, calling the future victim multiple times a day, accompanying her to health care appointments, dropping her off at work and waiting to pick her up afterward. He may offer financial support, spend money on her, or even provide housing. This assistance gradually leads to control over the victim’s finances and outside contacts, including family and friends, and even professional interactions.45 The perpetrator’s control engenders the victim’s growing dependence and isolation.

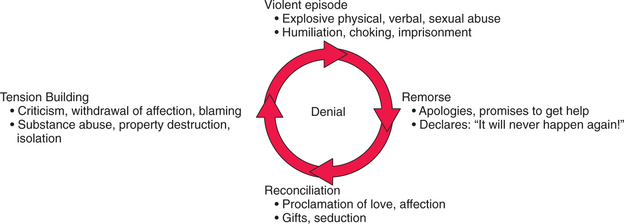

It is often some major life event for the couple46 (such as marriage, pregnancy, or birth) that triggers the first violent episode. (It may also be some form of recognition [e.g., professional advancement] of the victim that “provokes” the initial violence.) Couples generally respond with shock and revulsion, followed by a firm belief and commitment that this is an isolated, never-to-be-repeated incident. However, a pattern of repetitive, often predictable, and escalating violence ensues47 (Figure 82-1). Extreme remorse and reconciliation typically follow each act of violence. The perpetrator demonstrates his profuse contrition with outpourings of gifts and professions of love and affection. The victim is often sorry for the perpetrator’s “pain” and feels guilty for having provoked him. Both insist, and often believe, it will never happen again. This phase of reconciliation is followed by a period of growing tension that ultimately concludes in another violent eruption.31 Some victims experience such dread and terror during this insidious tension-building phase that they choose to provoke the violence to end their mounting anticipatory anxiety. As the violence continues, it escalates in both frequency and severity. Physical acts, such as pushing and shoving, may progress to punching, kicking, or burning. Domestic violence may involve forced sexual acts or the use of drugs or alcohol. The abuse may become life-threatening, especially with the introduction of weapons (such as clubs and knives). The presence or use of a gun obviously poses an even greater risk of lethality.3,19

This physical escalation is accompanied by emotional abuse calculated to further both the perpetrator’s control and dominance and the victim’s dependence and submission. Emotional abuse encompasses verbal and behavioral tactics (such as humiliation, intimidation, threats, and coercion). The abuser may purposely embarrass, berate, or humiliate the victim in front of others, including her children, family, friends, business associates, or even strangers. He may call her names and “put her down” to promote her sense of guilt and self-deprecation. He may attempt to manipulate her sense of reality to make her fear she is going crazy. Humiliating tactics also include treating her like a servant, forcing her to beg (e.g., for food, money, or access to clothing, physical needs, or bodily functions), and demanding illegal or demeaning behaviors, including sexual acts. Certain gestures or expressions may be purposefully linked to fearful consequences so that the look or gesture will in itself intimidate the victim and promote an ongoing dread of delayed consequences.1 Other intimidating strategies include reckless driving, brandishing weapons, destroying the victim’s property, or abusing her pets. Besides the threat of the violence itself, victims may be further terrorized by threats of abandonment, destitution, murder, legal action, deportation, psychiatric commitment, loss of (or harm to) their children, or harm to family. They may also be threatened with responsibility for the perpetrator’s suicide if they consider leaving. These coercive tactics underscore the victim’s reticence to leave what outwardly appears to be an untenable situation.

Children are both complications in, and casualties of, violent partner relationships. Suspicions of child abuse or witnessed abuse are reportable in most states, yet such reports may put the victim at increased risk. Children may be “drafted” by the perpetrator to join in the humiliation and the verbal abuse. They may be used as pawns to relay messages. Her children’s safety, or her access to them (e.g., loss of custody, visitation, or kidnapping), may be used as threats to keep the victim compliant within the relationship. While the effects of child abuse are not the topic of this chapter, there are known links between domestic partner abuse and child abuse that suggest they co-occur and may perpetuate the cycle of family violence.4–6,37,48

The nature of violent relationships hints at the myriad reasons victims stay in them. The physical and emotional damage of repetitive battering, the intermittent reinforcement of the cyclic dynamic, the true lack of resources, and the perceived and real danger keep victims from leaving. Continual berating leads to acceptance of the batterer’s conviction of the victim’s worthlessness. Victims come to believe they deserve their mistreatment and they should expect no better. Victims may feel not only humiliated, but ashamed, responsible, and guilty.46 They are isolated from family and friends, whom they may have helped drive away to quell the batterer’s suspicions and jealousy, in hopes of decreasing the tensions that inevitably lead to the next episode of violence. In fact, they are isolated from all outside contacts: medical, legal, professional, social, and community. Victims are without financial resources, because such dependence gives the perpetrator ultimate control. They may have been prevented from working or made to turn all earnings, money, and other assets over to the abuser. The fear of indigence, homelessness, and inability to care for oneself or one’s children is grounded in reality. A victim who has tried unsuccessfully to leave in the past will be unlikely to risk another attempt, especially if she experienced disbelief or lack of assistance from those who might have helped: family, police, medical or legal professionals, or social agencies. And finally, the remorse, affection, and avowals of reform after the explosive violence fuel the victim’s hope for change. Many victims do not want the relationship to end; they want to end the abuse.49

EVALUATION

Every psychiatric and every general medical assessment should include brief screening questions about violence. For reasons that should now be clear, many patients are wary of offering such information, but will respond truthfully to empathic probing. Both men and women should be asked whether they have experienced violence, either as a victim or a perpetrator. As this becomes more widely recognized as part of a general survey, patients are more accustomed to these questions and less likely to take offense. If that is not yet the case, a qualifying statement can be made first, such as the following: “There are certain questions that are part of a full evaluation that I ask all patients.” Asking “Have you been hit, kicked, punched, or otherwise hurt by someone within the past year? If so, by whom?” has been shown to identify over 70% of women in violent relationships, as identified by more extensive inventories.50 Questions about sexual assault and violence in past relationships are also important for both their effects on the patient and their predictive value. Women are more likely to be sexually assaulted by current or past partners than by strangers and are at increased risk if they have a history of assault. This questioning should be carried out in a straightforward, nonjudgmental fashion, in a private setting. Asking such questions in front of the perpetrator not only inhibits an honest response, but endangers the victim. In the case of non–English-speaking patients, intimates, family, or friends should never serve as interpreters.

Disclosure of current or previous abuse should trigger questions about the first episode, the worst episode, and the last episode.49 Children in the family require inquiry about whether they have witnessed or experienced violence. Most states have mandatory reporting requirements for physicians who suspect child abuse or neglect; this includes the witnessing of partner abuse. Patients should be informed about the potential need to file such a report.

In cases of violence, the medical record requires especially careful and thorough documentation31; it is the repository of medical evidence. An empathic general physician, knowledgeable and sensitive about issues of abuse, should conduct and record a complete physical examination, including a screening neurological examination for any focal findings or evidence of repetitive head trauma. Descriptions of injuries (including signs of sexual trauma) should be accompanied by explanatory drawings, diagrams, or photographs. Extra precautions may be necessary to maintain the patient’s privacy, safety, and confidentiality, especially in small or tight-knit community settings.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The broad spectrum of psychiatric disorders seen in victims of domestic violence may be triggered, worsened, or complicated by the abuse situation.34 After the initial outburst of violence, victims may have adjustment disorders. General ized anxiety may be triggered by the tension-building phase of the abuse cycle. Those victims genetically predisposed to anxiety may experience panic attacks or panic disorder (as the advent of domestic violence is certainly a major life event). Response to past trauma may be rekindled, exacerbating or inducing PTSD. Dissociative disorders are more common in victims who have also experienced childhood physical abuse or sexual trauma.37 Depression may develop, worsen, become treatment-resistant, or be associated with psychotic symptoms. Eating disorders are prevalent in abuse victims. Alcohol and drugs may be part of the coercion and abuse, or addiction may develop as victims seek to tolerate the violence or numb the pain. Victims may also suffer the effects of acute head injury or mental disorders caused by repetitive head trauma.

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

Treatment starts with detection, because no intervention can occur until the abuse is identified. RADAR49 (Table 82-4) is an acronym designed to remind physicians to screen, recognize, and treat abuse.

Source: Massachusetts Medical Society Committee on Violence, B. Herbert (chair), 2004.

A detailed and thoughtful safety plan considers the victim’s assets, supports, defenses, experience, function, and responsibilities.31,49 What immediate money and other financial resources are available to her? Who (e.g., family, friends, social, community, or legal agents) are the victim’s social supports? How has she coped or what strategies have been useful for her? What were the outcomes of any past attempts to leave or to alter the abuse cycle? How well is she currently functioning at home, at work, or elsewhere? Are there children, pets, or elders in the home, and are they also at risk? Details of the plan include mobility of all involved, access to phone and car, a safe destination, and timing. The plan may also include a safety contact person who will initiate such predetermined actions as calling the police if the victim does not arrive as planned at the safe destination. Women whose abuse encompasses sexual assault must also plan for prevention, detection, and treatment of sexually transmitted diseases or pregnancy.

Benzodiazepines and other sedating medications are relatively contraindicated in the treatment of victims who can ill afford further dulling or impairment in their ability to anticipate, to react, to flee, or to protect themselves (and their children). Addiction and diversion may also be issues, but of less importance.

1 Strauchler O, McCloskey K, Malloy K, et al. Humiliation, manipulation, and control: evidence of centrality in domestic violence against an intimate partner. J Fam Violence. 2004;19:339-354.

2 Brookoff D, O’Brien KK, Cook CS, et al. Characteristics of participants in domestic violence. JAMA. 1997;277:1369-1373.

3 Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Full report of the prevalence, incidence and consequences of violence against women: research report. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice, 2000. NCJ 183781

4 Bair-Merritt MH, Blackstone M, Feudtner C. Physical health outcomes of childhood exposure to intimate partner violence: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2006;117:278-290.

5 Becker F, French L. Making the links: child abuse, animal cruelty and domestic violence. Child Abuse Rev. 2004;13:399-414.

6 Nelson HD, Nygren P, McInerney Y, Klein J. Screening women and elderly adults for family and intimate partner violence: a review of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:387-396.

7 Ramsey J, Richardson J, Carter YH, et al. Should health professionals screen women for domestic violence? Systematic review. BMJ. 2002;325:314-318.

8 Rhodes KV, Drum M, Anliker E, et al. Lowering the threshold for discussions of domestic violence; a randomized controlled trial of computer screening. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1107-1114.

9 Chuang CH, Liebschutz JM. Screening for intimate partner violence in the primary care setting: a critical review. J Clin Outcomes Mgt. 2002;9:565-571.

10 Waalen J, Goodwin MM, Spitz AM, et al. Screening for intimate partner violence by health care providers. Barriers and interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19:230-237.

11 Rodriguez MA, Bauer HM, McLoughlin E, Grumbach K. Screening and intervention for intimate partner abuse: practices and attitudes of primary care physicians. JAMA. 1999;282:468-474.

12 Wilson M, Daly M. Spousal homicide risk and estrangement. Violence Vict. 1993;8:3-16.

13 Tolan P, Sorman-Smith D, Henry D. Family violence. Annu Rev Psychol. 2006;57:557-583.

14 Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2000;126:651-680.

15 Kimmel M. “Gender symmetry” in domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:1332-1363.

16 Field CA, Caetano R. Intimate partner violence in the US general population: progress and future directions. J Interpers Viol. 2005;20:463-469.

17 National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs (NCAVP): Annual report on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender domestic violence, 1998.

18 National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs (NCAVP): Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender domestic violence: 2003 supplement, 2003.

19 US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Homicide trends in the US. Intimate homicide, 2004. Available at www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/homicide/intimates.htm.

20 Abbott J, Johnson R, Koziol-McLain J, Lowenstein SR. Domestic violence against women: incidence and prevalence in an emergency department population. JAMA. 1995;273:1763-1767.

21 Dearwater SR, Coben JH, Campbell JC, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner abuse in women treated at community hospital emergency departments. JAMA. 1998;280:433-438.

22 Freund KM, Blackhall LJ. Identifying domestic violence in primary care practice. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:44-46.

23 Sethi D, Watts S, Zwi A, et al. Experience of domestic violence by women attending an inner city accident and emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2004;21:180-184.

24 Webster J, Holt V. Screening for partner violence: direct questioning or self-report? Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:299-303.

25 Gazmarian JA, Lazorick S, Spitz AM, et al. Prevalence of violence against pregnant women. JAMA. 1996;275:1915-1920.

26 Martin S, Mackie L, Kupper LL, et al. Physical abuse of women before, during and after pregnancy. JAMA. 2001;285:1581-1584.

27 McKibben L, DeVos E, Newberger E. Victimization of mothers of abused children: a controlled study. Pediatrics. 1989;84:532-535.

28 Stark E. Killing the beast within: woman battering and female suicidality. Int J Health Services. 1995;25:43-64.

29 Reade J. Approach to domestic violence. In: Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, editors. The MGH guide to psychiatry in primary care. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998.

30 Zachery MJ, Mulvihill MN, Burton WB, Goldfrank LR. Domestic abuse in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:796-803.

31 Bullock KA, Schornstein SL. Improving medical care for victims of domestic violence. Hosp Physician. 1998:42-58.

32 Holt VL, Kernic MA, Lumley T, et al. Civil protection orders and risk of subsequent police-reported violence. JAMA. 2002;288:589-594.

33 Kyriacou DN, Anglin D, Talliaferro E, et al. Risk factors for injury to women from domestic violence. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1892-1898.

34 Ehrensaft MK, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Is domestic violence followed by an increased risk of psychiatric disorders among women but not among men? A longitudinal cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:885-892.

35 Rubin JJ. Psychosomatic pain: new insights and management strategies. South Med J. 2005;98:1099-1110.

36 Golding JM. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: a meta-analysis. J Fam Violence. 1999;14:99-132.

37 McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, et al. Clinical characteristics of women with a history of childhood abuse. JAMA. 1997;277:1362-1368.

38 Nicolaidis C, Touhouliotis V. Addressing intimate partner violence in primary care: lessons from chronic illness management. Violence Vict. 2006;21:101-115.

39 Eisenstat SA, Bancroft L. Domestic violence. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:886-892.

40 Carr JL, VanDeusen KM. The relationship between family of origin violence and dating violence in college men. J Interpers Viol. 2002;17:630-646.

41 Leonard KE. Alcohol’s role in domestic violence: a contributing cause or excuse? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106(suppl 412):9-14.

42 Sharps PW, Campbell J, Campbell D, et al. The role of alcohol use in intimate partner femicide. Am J Addict. 2001;10:122-135.

43 Grisso JA, Schwarz DF, Hirschinger N, et al. Violent injuries among women in an urban area. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1899-1905.

44 Willis DG, Porche DJ. Male battering of intimate partners: theoretical underpinnings, intervention approaches, and implications. Nurs Clin North Am. 2004;39:271-282.

45 Swanberg JE, Logan TK, Macke C. Intimate partner violence, employment, and the workplace. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2005;6:286-312.

46 Arriaga XB, Capezza NM. Targets of partner violence: the importance of understanding coping trajectories. J Interpers Viol. 2005;20:89-99.

47 Walker LE. The battered woman syndrome. New York: Springer, 1984.

48 Wolfe DA, Crooks CV, Lee V, et al. The effects of children’s exposure to domestic violence: a meta-analysis and critique. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2003;6:171-187.

49 Massachusetts Medical Society Committee on Violence, Alpert EJ, Herbert B. Partner violence, how to recognize and treat victims of abuse: a guide for physicians and other health care professionals, ed 4, Waltham, MA: Massachusetts Medical Society, 2004.

50 Feldhaus KM, Kaziol-McLain J, Amsbury HL, et al. Accuracy of 3 brief screening questions for detecting partner violence in the emergency department. JAMA. 1997;227:1357-1361.