Arterial Puncture

Arterial Puncture

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• An arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis measures the pH and the partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) and carbon dioxide (PaCO2). ABG samples are also analyzed for oxygen saturation (SaO2) and for bicarbonate (HCO−3) values. These analyses are done primarily to evaluate a patient’s oxygenation status, acid-base balance, and ventilation.3,5 Additional laboratory tests (e.g., ammonia and lactate levels) can be performed on arterial blood samples.

• Patient indications for ABGs vary and include patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and pneumonia. ABG analysis frequently is performed on patients in shock, receiving cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), or experiencing changes in respiratory therapy or status.3,5

• Knowledge of principles of aseptic technique is necessary.

• Knowledge is needed of the anatomy and physiology of the vasculature and adjacent structures.

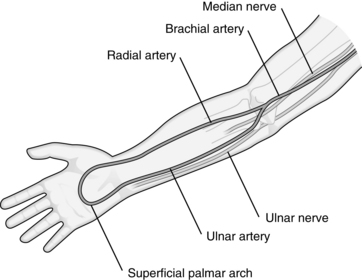

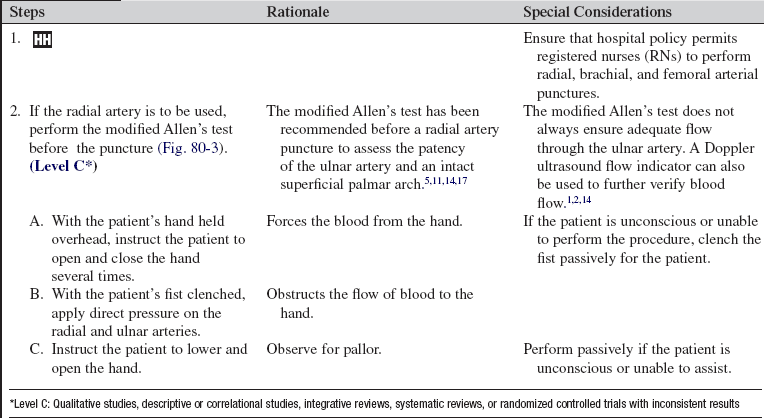

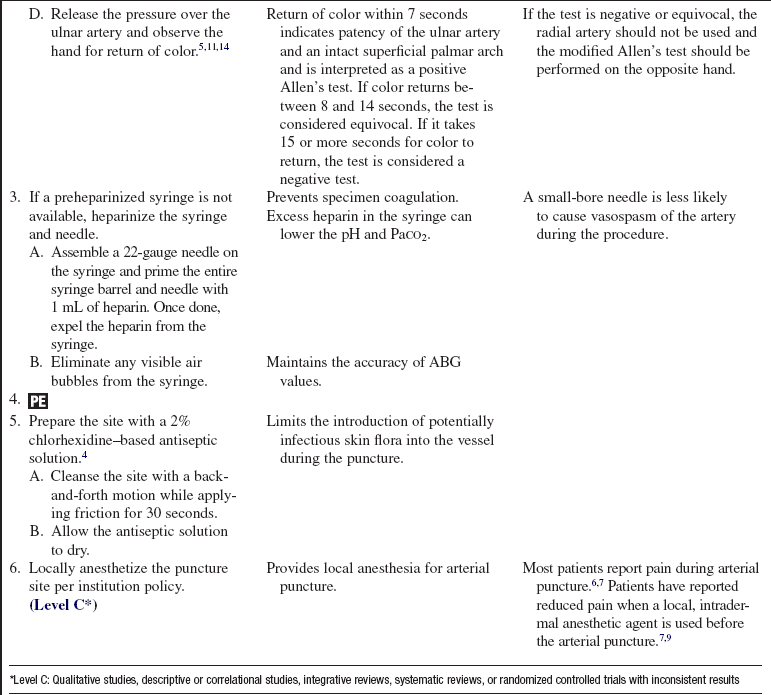

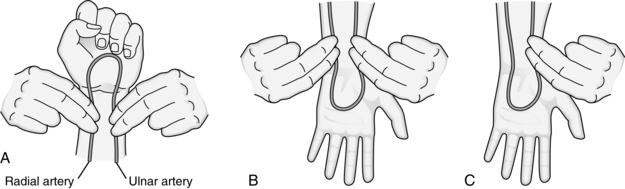

• The brachial artery is a continuation of the axillary artery in the upper extremity. It bifurcates just below the elbow (Fig. 80-1). From the bifurcation, the ulnar artery moves down the forearm on the medial side and the radial artery on the lateral side.20

• The preferred artery for arterial puncture is the radial artery. Although this artery is smaller than the ulnar artery, it is more superficial and can be more easily stabilized during the procedure.6 The use of the brachial artery is a safe and reliable alternative site for arterial puncture.16

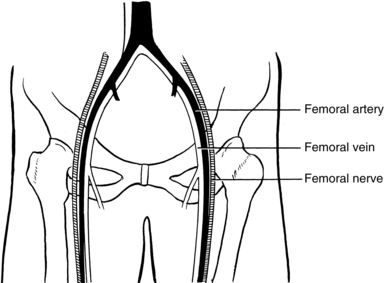

• At times, the femoral artery is used for arterial puncture. The use of this artery can be technically difficult because of the proximity of the artery to the femoral vein (Fig. 80-2).

• Arterial cannulation is considered for patients who need frequent arterial blood samples, continuous arterial pressure monitoring, or evaluation of vasoactive medication therapy (see Procedures 61 and 62).5

• The most common complications associated with arterial puncture include pain, vasospasm, hematoma formation, infection, hemorrhage, and neurovascular compromise.5,9,16,19

• Site selection proceeds as follows:

Use the radial artery as first choice. The radial artery is small and easily stabilized as it passes over a bony groove located at the wrist (see Fig. 80-1).

Use the radial artery as first choice. The radial artery is small and easily stabilized as it passes over a bony groove located at the wrist (see Fig. 80-1).

Use the brachial artery as second choice, except in the presence of poor pulsation from shock, obesity, or sclerotic vessel (e.g., because of previous cardiac catheterization). The brachial artery is larger than the radial artery. Hemostasis after arterial puncture is enhanced by its proximity to bone if the entry point is approximately 1.5 inches above the antecubital fossa (see Fig. 80-1).

Use the brachial artery as second choice, except in the presence of poor pulsation from shock, obesity, or sclerotic vessel (e.g., because of previous cardiac catheterization). The brachial artery is larger than the radial artery. Hemostasis after arterial puncture is enhanced by its proximity to bone if the entry point is approximately 1.5 inches above the antecubital fossa (see Fig. 80-1).

Use the femoral artery in the case of cardiopulmonary arrest or altered perfusion to the upper extremities. The femoral artery is a large superficial artery located in the groin (see Fig. 80-2). It is easily palpated and punctured. Complications related to femoral artery puncture include hemorrhage and hematoma because bleeding can be difficult to control; inadvertent puncture of the femoral vein because of the close proximity of the vein to the artery; infection because aseptic technique in the groin area is difficult to maintain; and limb ischemia if the femoral artery is damaged.

Use the femoral artery in the case of cardiopulmonary arrest or altered perfusion to the upper extremities. The femoral artery is a large superficial artery located in the groin (see Fig. 80-2). It is easily palpated and punctured. Complications related to femoral artery puncture include hemorrhage and hematoma because bleeding can be difficult to control; inadvertent puncture of the femoral vein because of the close proximity of the vein to the artery; infection because aseptic technique in the groin area is difficult to maintain; and limb ischemia if the femoral artery is damaged.

EQUIPMENT

• One prepackaged ABG kit that contains the following:

One 20-gauge to 25-gauge, 1-inch to 1.5-inch hypodermic needle (note: longer needles are needed for brachial and femoral artery puncture)

One 20-gauge to 25-gauge, 1-inch to 1.5-inch hypodermic needle (note: longer needles are needed for brachial and femoral artery puncture)

One 1- to 5-mL preheparinized (if available) syringe with a rubber stopper or cap

One 1- to 5-mL preheparinized (if available) syringe with a rubber stopper or cap

One 1-mL ampule of sodium heparin, 1:1000 concentration (if preheparinized syringe is not available)

One 1-mL ampule of sodium heparin, 1:1000 concentration (if preheparinized syringe is not available)

2% chlorhexidine–based antiseptic solution

2% chlorhexidine–based antiseptic solution

• Appropriate laboratory form, specimen label

• One pair of nonsterile examination gloves and eye protection

• 1% lidocaine (without epinephrine), 1-mL, or eutectic mixture of local anesthetics (EMLA) cream

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the reason for the arterial puncture to the patient and family.  Rationale: Clarification of information is an expressed patient and family need and helps to diminish anxiety, enhance acceptance, and encourage questions.

Rationale: Clarification of information is an expressed patient and family need and helps to diminish anxiety, enhance acceptance, and encourage questions.

• Describe the overall steps of the procedure, including the patient’s role in the procedure.  Rationale: This explanation decreases patient anxiety, enhances cooperation, and provides an opportunity for the patient to voice concerns and prevents accidental movement during the procedure.

Rationale: This explanation decreases patient anxiety, enhances cooperation, and provides an opportunity for the patient to voice concerns and prevents accidental movement during the procedure.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Determine the need for arterial cannulation versus puncture.  Rationale: Repeated arterial punctures increase patient discomfort and the risk for complications.

Rationale: Repeated arterial punctures increase patient discomfort and the risk for complications.

• Assess for factors that influence ABG measurements, including anxiety, endotracheal suctioning, nebulizer treatment, change in oxygen therapy/ventilator settings, patient positioning, body temperature, metabolic rate, and respiratory rate.  Rationale: These conditions or therapies can alter blood gas analysis.

Rationale: These conditions or therapies can alter blood gas analysis.

• Assess the patient’s current anticoagulation therapy, known blood dyscrasias, and pertinent laboratory values (e.g., platelets, partial thromboplastin time [PTT], prothrombin time [PT], and international normalized ratio [INR]) before the procedure.  Rationale: Anticoagulation therapy, blood dyscrasias, or alterations in coagulation studies could prolong hemostasis at the puncture site and increase the risk for hematoma formation or hemorrhage.

Rationale: Anticoagulation therapy, blood dyscrasias, or alterations in coagulation studies could prolong hemostasis at the puncture site and increase the risk for hematoma formation or hemorrhage.

• Assess the patient’s allergy history (e.g., lidocaine, antiseptic solutions, tape).  Rationale: Assessment decreases the risk for allergic reactions.

Rationale: Assessment decreases the risk for allergic reactions.

• Assess the patient’s past surgical history (e.g., use of radial artery for coronary artery bypass surgery, fistulas, or shunts).  Rationale: Arterial puncture should be avoided in extremities affected by these conditions.

Rationale: Arterial puncture should be avoided in extremities affected by these conditions.

• Ascertain the patient’s nondominant hand, if possible.  Rationale: A complication to the nondominant hand may have fewer consequences.

Rationale: A complication to the nondominant hand may have fewer consequences.

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that the patient and family understand preprocedural teaching. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Perform a preprocedure verification and time-out, if non-emergent.  Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

• If the patient is receiving oxygen or mechanical ventilation, check that the current therapy has been underway for at least 20 to 30 minutes before obtaining ABGs.5,8,11,14,18  Rationale: Accurate laboratory results are achieved, which is most important in patients with an abnormal ventilation/perfusion ratio.14

Rationale: Accurate laboratory results are achieved, which is most important in patients with an abnormal ventilation/perfusion ratio.14

• Position the patient appropriately.  Rationale: Positioning enhances the accessibility to the insertion site and promotes patient comfort.

Rationale: Positioning enhances the accessibility to the insertion site and promotes patient comfort.

Assist the patient to a semirecumbent position.

Assist the patient to a semirecumbent position.  Rationale: A position of comfort decreases anxiety and may facilitate respiratory effort.

Rationale: A position of comfort decreases anxiety and may facilitate respiratory effort.

Elevate and hyperextend the wrist. A small rolled towel may be placed under the wrist for support.

Elevate and hyperextend the wrist. A small rolled towel may be placed under the wrist for support.  Rationale: This action moves the artery closer to the skin surface, making the artery easier to palpate.

Rationale: This action moves the artery closer to the skin surface, making the artery easier to palpate.

Palpate for the presence of a strong radial pulse.

Palpate for the presence of a strong radial pulse.  Rationale: Identification and localization of the pulse increases the chance of a successful arterial puncture.

Rationale: Identification and localization of the pulse increases the chance of a successful arterial puncture.

Assist the patient to a semirecumbent position.

Assist the patient to a semirecumbent position.  Rationale: A position of comfort decreases anxiety and may facilitate respiratory effort.

Rationale: A position of comfort decreases anxiety and may facilitate respiratory effort.

Elevate and hyperextend the patient’s arm. A small pillow may be placed under the arm for support.

Elevate and hyperextend the patient’s arm. A small pillow may be placed under the arm for support.  Rationale: This action increases accessibility for puncture.

Rationale: This action increases accessibility for puncture.

Rotate the patient’s arm and palpate for the presence of a strong brachial pulse.

Rotate the patient’s arm and palpate for the presence of a strong brachial pulse.  Rationale: Identification and localization of the pulse increase the chance of a successful arterial puncture.

Rationale: Identification and localization of the pulse increase the chance of a successful arterial puncture.

Assist the patient to a supine, straight-leg position.

Assist the patient to a supine, straight-leg position.  Rationale: This position provides the best position for localizing the femoral artery pulse.

Rationale: This position provides the best position for localizing the femoral artery pulse.

Palpate for the presence of a strong femoral pulse.

Palpate for the presence of a strong femoral pulse.  Rationale: Identification and localization of the pulse increase the chance of a successful arterial puncture.

Rationale: Identification and localization of the pulse increase the chance of a successful arterial puncture.

References

![]() 1. Abu-Omar, Y, et al. Duplex ultrasonography predicts safety of radial artery harvest in the presence of an abnormal Allen test. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004; 77:116–119.

1. Abu-Omar, Y, et al. Duplex ultrasonography predicts safety of radial artery harvest in the presence of an abnormal Allen test. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004; 77:116–119.

2. Barone, JE, Madlinger, RV. Should an Allen Test be performed before artery cannulation. J Trauma. 2006; 61:468–470.

3. Carlson KK, ed. Advanced critical care nursing. St Louis: Saunders, 2009.

![]() 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. MMWR. 2002; 51(RR-10):1–31.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. MMWR. 2002; 51(RR-10):1–31.

5. Chernecky CC, Berger BJ, eds. Laboratory tests and diagnostic procedures, ed 5, St Louis: Saunders, 2008.

![]() 6. Flynn JC, ed. Procedures in phlebotomy, ed 3, St Louis: Saunders, 2004.

6. Flynn JC, ed. Procedures in phlebotomy, ed 3, St Louis: Saunders, 2004.

![]() 7. Giner, J, et al. Pain during arterial puncture. Chest. 1996; 110:1443–1445.

7. Giner, J, et al. Pain during arterial puncture. Chest. 1996; 110:1443–1445.

![]() 8. Hess, D, et al. The validity of assessing arterial blood gases 10 minutes after an Fio2 change in mechanically ventilated patients without chronic pulmonary disease. Respir Care. 1985; 30:1037–1041.

8. Hess, D, et al. The validity of assessing arterial blood gases 10 minutes after an Fio2 change in mechanically ventilated patients without chronic pulmonary disease. Respir Care. 1985; 30:1037–1041.

9. Hudson, TL, Dukes, SF, Reilly, K. Use of local anesthesia for arterial punctures. Am J Crit Care. 2006; 15:595–599.

![]() 10. Hussey, VM, Poulin, MV, Fain, JA. Effectiveness of lidocaine hydrochloride on venipuncture sites. AORN J. 1997; 66:472–475.

10. Hussey, VM, Poulin, MV, Fain, JA. Effectiveness of lidocaine hydrochloride on venipuncture sites. AORN J. 1997; 66:472–475.

11. Intravenous Nurses Society. Infusion nursing standards of practice. J Infus Nurs. 2006; 29(1S):S1–S90.

![]() 12. Joly, LM, et al. Topical lidocaine-prilocaine cream (EMLA) versus local infiltration of anesthesia for radial artery cannulation. Anesth Analg. 1998; 87:403–406.

12. Joly, LM, et al. Topical lidocaine-prilocaine cream (EMLA) versus local infiltration of anesthesia for radial artery cannulation. Anesth Analg. 1998; 87:403–406.

![]() 13. Lander, J, et al, Evaluation of a new topical anesthetic agent. a pilot study. Nurs Res 1996; 45:50–52.

13. Lander, J, et al, Evaluation of a new topical anesthetic agent. a pilot study. Nurs Res 1996; 45:50–52.

![]() 14. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Procedures for the collection of arterial blood specimens. approved standard H11-A4. ed 4. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA, 2004.

14. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Procedures for the collection of arterial blood specimens. approved standard H11-A4. ed 4. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA, 2004.

![]() 15. Nott, M, Peacock, J, Relief of injection pain in adults. EMLA cream for 5 minutes before venipuncture. Anaesthesia 1990; 45:772–774.

15. Nott, M, Peacock, J, Relief of injection pain in adults. EMLA cream for 5 minutes before venipuncture. Anaesthesia 1990; 45:772–774.

![]() 16. Okeson, GC, Wulbrecht, PH. The safety of brachial artery puncture for arterial blood sampling. Chest. 1998; 14:748–751.

16. Okeson, GC, Wulbrecht, PH. The safety of brachial artery puncture for arterial blood sampling. Chest. 1998; 14:748–751.

17. Oettle, AC, et al. Evaluation of Allen’s test in both arms and arteries of left and right-handed people. Surg Radiol Anat. 2006; 28:3–6.

![]() 18. Sherter, CB, et al. Prolonged rate of decay of arterial Po2 following oxygen breathing in chronic airway obstruction. Chest. 1975; 67:259.

18. Sherter, CB, et al. Prolonged rate of decay of arterial Po2 following oxygen breathing in chronic airway obstruction. Chest. 1975; 67:259.

19. Siegel, JD, et al, and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/pdf/guidelines/Isolation2007.pdf, 2007 [retrieved October 10, 2008].

20. Thibodeau, GA, Patton, KT. Anatomy and physiology,, ed 6. St Louis: Mosby; 2007.

![]() 21. Tran, NQ, Pretto, JJ, Worsnop, CJ. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of topical amethocaine in reducing pain during arterial puncture. Chest. 2002; 122:1357–1360.

21. Tran, NQ, Pretto, JJ, Worsnop, CJ. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of topical amethocaine in reducing pain during arterial puncture. Chest. 2002; 122:1357–1360.