CHAPTER 8. Ethical issues associated with the reporting of child abuse

L earning objectives

▪ Define child abuse.

▪ Discuss critically the bases upon which child abuse and its prevention stands as an important moral issue not just for nurses, but for the community at large.

▪ Explore common ethical issues associated with the identification and prevention of child abuse.

▪ Examine critically the moral responsibilities of nurses and the broader nursing profession in regard to the mandatory and voluntary notification of child abuse.

I ntroduction

Historically, dating back to ancient times, children have suffered violence (been menaced, maimed and murdered) at the hands of adults (Johnstone 1999b). Today, the abuse of children constitutes one of the world’s most longstanding and tragic public health issues (World Health Organization [WHO] 2002b; WHO & International Society for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect [ISPCAN] 2006). Child abuse continues to occur in epidemic proportions and, despite global efforts to redress it, its incidence and negative impact continues to be largely under-recognised, under-reported and poorly addressed by governments across the globe (WHO 2001b: 2; see also Pinheiro 2006; WHO & ISPCAN 2006). Although child abuse and its adverse effects on the health and wellbeing of children (and the adults they become) are ‘more visible’ today, as noted by the WHO and the International Society for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (ISPCAN), the degree of this increased visibility ‘is far from sufficient’ (WHO & ISPCAN 2006: 1).

In 1999 the WHO estimated that globally over 40 million children aged 0–14 years suffer from abuse and neglect each year, and require health and social care (WHO 1999). The WHO further estimates that around 53000 children are murdered each year, and that between 73 million boys (7%) and 150 million girls (14%) under the age of 18 years are subjected to some form of sexual violence or forced sexual intercourse each year (WHO 2007a: 1). In some countries, it has been estimated that between 25% and 50% of children suffer severe and frequent physical abuse (including being beaten, kicked or tied up by parents) (WHO & ISPCAN 2006: 11). The burden of ill-health caused by child abuse-related injuries has been calculated to be ‘staggering in terms of cost and socio-economic development’ (WHO 1999). In the United States (US), for example, it has been conservatively estimated that the financial cost of child abuse is around $103.8 billion in value per year (Wang & Holton 2007).

Child maltreatment (literally the ‘wrong handling’ of children) and its harmful consequences can and ought to be prevented (WHO & ISPCAN 2006). As the United Nations (UN) has made clear:

no violence against children is justifiable, and all violence against children is preventable … whether accepted as ‘traditional’ or disguised as ‘discipline’. [emphasis original]

(Pinheiro 2006: 3)

Nurses, like others, have a strong professional, legal and moral obligation to take appropriate action to prevent child maltreatment and the burden of suffering that is so demonstrably associated with it. However, the nature and implications of this obligation requires critical examination in order to improve understanding of the conditions under which it might be held to be binding, and to ensure that it is fulfilled in a manner that genuinely maximises the moral interests of vulnerable children.

Historically, the problem of child maltreatment and protection has prompted a variety of responses at a social, political, legal and professional level (Johnstone 1999b). Notable among these has been the controversial introduction of contemporary mandatory (and permissive) reporting legislation. The introduction of this legislation has had important implications for the nursing profession as a whole as well as for individual nurses.

Today, the mandatory and voluntary reporting of child maltreatment constitutes an important ethical issue for members of the nursing profession, and for authorities formally charged with the legal responsibility of regulating nursing standards and practice. Despite this, the issue has received relatively little attention in the nursing (ethics) literature, and has received even less attention in mainstream child abuse, bioethics, jurisprudence and other related literature (see also Nayda 2002). Of particular concern, and the subject of this chapter, is the lack of attention given to examining the nature and implications of the (professional, legal and moral) obligation of nurses to report child maltreatment, and the ‘special issues’ this obligation may raise for individual members of the nursing profession. It is an important aim of this chapter to redress this oversight, and to identify and address key issues warranting attention by individual nurses, nurse registering authorities, professional nursing organisations, and others who are not nurses but whose work may involve liaison and collaboration with members of the nursing profession.

In the discussion to follow, attention will be given to providing a definition of child abuse, to providing a brief historical overview of the development of the modern child protection movement, to examining why child abuse constitutes a significant moral issue for members of the nursing profession and the community at large, and to addressing some of the key ethical issues raised by mandatory reporting requirements.

W hat is child abuse?

Incredibly, up until 1999, there was no internationally recognised operational definition of child abuse (Johnstone 1999b). This situation made the conduct of comparative research and scholarship on the incidence and impact of child abuse (in all its forms) very difficult — a situation that, in turn, added to the complexities of trying to get ‘good information’ about the problem and to inform the development and operationalisation of effective child protection policies and programs (WHO 2002b). Following the publication of a study by ISPCAN (published 2000), in which the definitions of child abuse from 58 countries were compared, this situation changed. In 1999, the WHO Consultation on Child Abuse Prevention drafted the following definition (now recognised as the universal definition of child abuse):

Child abuse or maltreatment constitutes all forms of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect or negligent treatment or commercial or other exploitation, resulting in actual or potential harm to the child’s health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power.

(WHO 1999)

In the process of formulating and adopting this definition, there has also emerged a much greater — and long overdue — appreciation of child abuse constituting an act of violence, which in turn has been defined as:

The intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against another person or against oneself or a group of people, that results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment or deprivation.

(WHO 1995)

This shift in thinking and attitude is now seeing a concerted effort, locally and globally, to end violence against children (Pinheiro 2006).

T he development of the modern child protection movement in N orth A merica

In the US, reported cases of child abuse date back to the 17th century. In 1655, for example, a master was convicted in a Massachusetts’ court and punished for the death of his 12-year-old apprentice (Watkins 1990: 500). Almost 200 years later, in Johnson v State (1840), ‘a Tennessee parent was charged with excessive punishment of a child’ (Watkins 1990: 500). In this case, the court held:

A parent has the right to chastise a disobedient child, but if he [sic] exceeds the bounds of moderation, and inflicts cruel punishment, he [sic] is a trespasser, and liable to indictment therefor[sic], the excess which constitutes the offence being, not a conclusion of law, but a question of fact for the determination of the jury.

( Johnson v State (1840), cited in Watkins 1990: 500)

It is also known that in the early 1820s, public authorities in New York recognised their duty to intervene in cases of child abuse (including parental cruelty and gross neglect). This, however, often resulted in children being indentured (i.e. placed into service or an apprenticeship) in conditions as bad or worse than those from which they had originally been removed (Folks 1902, cited in Watkins 1990: 500). The practice of indenture did not fade out until about 1875 following the passage of the 13th Amendment in 1867, which ended not only slavery but ‘involuntary servitude within the USA or any place subject to its jurisdiction’ (Watkins 1990: 500).

Significantly, laws which could be used to protect children from cruelty existed long before the date of the 13th Amendment being passed. As an early commentator on the care of destitute, neglected and delinquent children noted, during the 1800s, ‘laws for the prevention of cruelty to children were considered ample, but it was nobody’s business to enforce the laws’ (Folks 1902, cited in Watkins 1990: 501, emphasis added). Although American ‘state statutes were adopted after 1825 that established a public duty to intervene in cases of cruelty or neglect of children’, these were rarely enforced (Folks 1902; Thomas 1972, cited in Watkins 1990: 501). Further, these statutes stopped short of mandating ‘a responsibility to search out children at risk’ (Watkins 1990: 500). Significantly, it was not until after the landmark (and now legendary) Mary Ellen child abuse case of 1874 (described below) that this situation began to change, largely due to the establishment and development of a formal movement for the protection of children which was initiated as a result of the widespread publicity given to this case. A key feature of this movement was to make it ‘somebody’s business’ to enforce child protection laws.

T heM ary E llen case

The Mary Ellen case involved a small child (of approximately 10 years of age) who had been severely abused by her guardians since the time of her indenture in 1866. A visitor among the poor, Mrs Wheeler, received complaints about the child’s maltreatment and, when unable to get assistance from either the police, benevolent societies or charitable gentlemen, approached the president of the society for the Protection of Animals for assistance in gaining protection for the child against further cruelty by her guardians (Lewin 1994: 15; Watkins 1990: 501). The president of the society ultimately agreed to help and, with his assistance, the case was brought before the New York State Supreme Court. Mary Ellen is reported to have appeared in court ‘wrapped in a carriage blanket and wearing ragged garments. Her body was bruised, and she had a gash above her left eye and cheek where she had been struck with scissors’ (Lewin 1994: 15).

The court case was successful, the outcome of which resulted in Mary Ellen being placed in the protective care of Mrs Wheeler. Mary Ellen’s abusive female guardian, meanwhile, was convicted of criminal assault and sentenced to ‘one year in the Penitentiary at hard labour’ (Watkins 1990: 502). Following the publicity given to this case, the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NYSPCC) was formed in 1874 and ‘became the child protection and rescue model for several US states and foreign countries’ (Watkins 1990: 501; see also Lewin 1994: 15; Goddard 1996: 96). A century later, in 1976, the first international conference on child abuse was held in Geneva. Among other things, this conference increased the world’s understanding that the problem of child maltreatment was not just a local or a national one, but was unequivocally international in its scope (Fogarty & Sargeant 1989: 149).

D evelopment of the modern child protection movement in E ngland and A ustralia

The North American experience was to be influential in the development of the child protection movement in the United Kingdom, with the first Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children in England being established in 1883 and ultimately receiving Queen Victoria’s patronage in 1889 (Fogarty & Sargeant 1989: 17). Like its North American counterparts, this society aimed, among other things, to achieve specific child protection and rescue law reforms, which up until then had failed to be passed. For example, in the 1870s, attempts to introduce anti-cruelty legislation into the English parliament were ‘entirely rebuffed’ with the prime minister of the day, Lord Shaftesbury, defending:

the evils you state are enormous and indisputable, but they are so private, internal and domestic in character as to be beyond the reach of legislation, and the subject would not, I think, be entertained in either House of Parliament.

(cited in Fogarty & Sargeant 1989: 17)

Australia, as a colony of England, was very much influenced by British attitudes and political antipathy in dealing formally with the issue of cruelty to children (Renvoize 1993: 31; Fogarty & Sargeant 1989: 16–17). Of particular interest to this discussion is the situation in the Australian state of Victoria which was not exempt from the problem of child abuse. For example, in 1863, inquests into the deaths of children under 3 years of age found that approximately one-quarter had died as a result of causes ‘denoting neglect, ignorance or maltreatment’ (Gandevia 1978, cited by Goddard 1996: 10). Although child-specific welfare legislation was passed as early as 1864 (the Neglected and Criminal Children’s Act) and a Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Children (modelled on the British society) established in 1897, as Fogarty and Sargeant comment (1989: 16):

Throughout the 19th century the State displayed a deliberate reticence to intervene in family matters. Whereas factory legislation and educational developments increasingly took cognisance of the particular needs of children and there was legislation protecting animals against cruelty, there was a marked antipathy to protect children against maltreatment by their parents or custodians.

A notable example of this antipathy can be found in an argument that was advanced against a proposed Bill introduced into the Victorian parliament in 1891 and which was aimed at ‘making incest a criminal offence’ (Renvoize 1993: 31). In rejecting the passage of the Bill (which was later passed), it was argued ‘that it would be better that a few persons should escape than that such a monstrous clause as this should be placed upon the statute book in this colony’ (Renvoize 1993: 31). Later examples show that this antipathy persisted well into the 20th century. For example, between 1966 and 1968, concern about child maltreatment and protection in Victoria was again highlighted when two medical researchers, publishing in the Australian Medical Journal, recommended the introduction of mandatory reporting laws (Birrell & Birrell 1966, 1968). The government of the day, however, rejected this recommendation on grounds that it would ‘run counter to “welfare ideology” and could lead to hysteria and an urge to punish cruel parents’ (Hiskey 1980, cited in Mendes 1996: 27). In its stead, a system of voluntary reporting was recommended. A decade later, in 1986, a recommendation for mandatory reporting was again opposed by the government of the day, this time on grounds that ‘it was punitive rather than preventive and likely to lead to a large increase in false reports’ (Colyer 1986, cited in Mendes 1996: 27).

C hild abuse in the cultural context of A ustralia

Today, the issue of child maltreatment and the need for effective child protection services remains problematic and an ‘endless challenge’ in countries around the world, including Australia. According to the latest figures released by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), the number of child protection notifications between 1999 and 2005 has more than doubled from 107134 (for the period 1999–2000) to 252831 (for the period 2004–2005), with the number of substantiations also increasing (AIHW 2006: xiii). These figures have been interpreted by some as indicating that an ‘Australian child was harmed, or found likely to be harmed, every 11 minutes in 2004–2005’ (NAPCAN Foundation 2006). Worryingly, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are conspicuously over-represented in the child protection figures and systems reported.

It has long been evident that ‘the system’ of child protection in Australia — like its overseas counterparts — has not been able to cope with the increase in demands that have constantly been placed upon it. Despite a rise in the reporting of child abuse, significant numbers of children are still maimed and killed each year as a result of abuse received at the hands of their primary carers (AIHW 2006; Strang 1996). A troubling aspect of this scenario is that in Australia, as has been shown to be the case overseas, very often ‘the circumstances leading to the most serious cases of child abuse almost always were known to the authorities, but there was no intervention because no-one would take responsibility’ ( Monash Review 1986: 11, emphasis added). In 1996 these failures of the Australian child protection system were described by one critic as a ‘national tragedy’, and prompted calls by the then Chief Justice of the Family Court, Justice Alastair Nicholson, for the system to be investigated by a royal commission of inquiry (Milburn 1996: 3). This call has, however, been largely ignored at both a social and political level (Johnstone, 1999b, 1999c). Over a decade later, child protection authorities are still quoted in the Australian news media as stating that ‘child protection systems across the country [are] poorly monitored’ (Hannan 2006: 4) and that there is an urgent need for a national non-partisan, sustainable and integrated policy platform in the areas of child development and child protection (Gaughwin 2007: 13).

Important questions remain as to why there is such apathy, at all social, cultural, political and legal levels, to challenge and change the status quo. There are many reasons for this — including, but not limited to: the emotional sensitivities involved, the lack of understanding of the serious long-term health effects of child maltreatment (not to mention its economic costs as well), a lack of awareness of effective prevention strategies, and the ‘pervasive demand for immediate returns on public investments’ (WHO & ISPCAN 2006: viii). What, perhaps, also lies at the basis of this social and political inertia is an even more insidious moral inertia and a culpable lack of moral will to challenge and change the status quo. What will shift this moral inertia remains an open question. What is certain, however, is that this moral malaise will continue until it is recognised and understood that child maltreatment is most profoundly a moral problem and, as such, deserves a sustained and comprehensive moral response.

W hat makes child abuse a bona fide and significant moral issue?

Child abuse constitutes a significant moral problem and, as such, demands a substantial moral response. Reasons for this are outlined below.

As previously considered in Chapter 3 of this book, it is generally accepted that something involves a (human) moral/ethical problem where it has as its central concern:

▪ the promotion and protection of people’s genuine wellbeing and welfare (including their interests in not suffering unnecessarily)

▪ responding justly to the genuine needs and significant interests of different people

▪ determining and justifying what constitutes right and wrong conduct in a given situation.

Adjunct to these concerns is an additional consideration, namely, that people have a moral responsibility to not cause unnecessary harm to others and, where able, ought to come to the aid of those who are suffering and in distress. As Amato (1990) notes in his Victims and values: a history and a theory of suffering (p 175):

There is an elemental moral requirement to respond to innocent suffering. If we were not to respond to it and its claims upon us, we would be without conscience and, in some basic sense, not completely human. And without compassion for others and passion for the causes on behalf of human wellbeing, what is best in our world would be missing.

These considerations all apply in the case of child abuse. As can be readily demonstrated, the problem of child abuse fundamentally concerns:

▪ promoting and protecting the wellbeing and welfare of children at risk of harm because of the abuse and neglect by more powerful others

▪ protecting children from this harm, requiring a careful calculation and balancing of the needs and interests of ‘different people’; for example, the children themselves, their primary caregivers (who are often, although not always, the abusers), others (such as family, friends) who may also have an important relationship with the child, prospective notifiers (who may themselves sometimes experience negative outcomes — including violence and abuse — as a result of their interventions aimed at protecting children at risk), society as a whole and, not least, future generations (who may find themselves unwitting participants in the sequelae of intergenerational abuse)

▪ determining and justifying the ‘rightness’ and ‘wrongness’ of intervening or not intervening in a case of known or suspected child abuse.

Adjunct to these concerns is an additional consideration involving the moral responsibility people have to not cause unnecessary harm to children and, where able, to come to the aid of children who are suffering and in distress as a result of being maltreated and/or neglected by others.

Underscoring child abuse as a moral problem are a number of other important considerations revolving around the extraordinary vulnerability of children generally. Children are among the most vulnerable members of our community. For the most part, they are unable to protect themselves from the harms imposed on them by people more powerful than themselves. Invariably children have to rely on others for help if their wellbeing and welfare is to be safeguarded. It has long been recognised that without intervention and help offered by others, the abuse and neglect of children rarely stops (Child Protection Victoria 1993: 9; Goddard 1996). Historically, however, children have not always been able to rely on others (including benevolent citizens, health professionals and public officials) to intervene and help them (Johnstone 1999b). Nor have they been able to rely on legal law and its processes. As has been pointed out elsewhere, children have long been considered ‘different’ under law and stand as the ‘paradigmatic group excluded from traditional liberal rights’ otherwise accorded to and protective of autonomous adults (Minow 1990: 283).

Equally troubling, neither have children been able to rely on ethics/morality to protect them. Historically, as in the case of law, ethics has also treated children as ‘different’; specifically, as not deserving the moral respect otherwise accorded to rationally competent adults (usually men) and which, if accorded to children, could have resulted in ‘substantial [and unwanted] intrusion’ into the lives of parents (especially fathers) and guardians (male benefactors) (adapted from Schrag 1995: 357). Because of not being able to rely on others, law or ethics for help, children historically have remained at risk of and have experienced otherwise avoidable harms which, if experienced by adults, would have been (and would be) universally condemned, even by the most rudimentary of moral calculations, as being morally unacceptable.

In light of these and other considerations, it is manifestly evident not only that child abuse is a significant moral problem, but that it warrants a substantial moral response. To be effective this response must include moral initiative and action at an individual, group, community and state/territory level aimed at providing genuine presence (‘being there’) for the children who require the assistance of others in order to get the protection they need from a situation of potential or actual abuse and/or neglect.

T he problem of ambivalence towards the moral entitlements of children

In an attempt to redress the historical and legitimated vulnerability of children in the case of child abuse and neglect, governments have responded by enacting either mandatory or voluntary reporting laws obligating certain people (on either legal or moral grounds) to intervene by reporting known or suspected cases of child abuse to child protection services. This response has not been without controversy, however. Pivotal to the controversy have been variant moral beliefs, values and attitudes concerning what constitutes the morally most appropriate response to child abuse given the complexity of overlapping relationships, responsibilities and variant moral calculations that are inherent in any potential or actual child abuse situation. So intense has been this controversy that, in some instances, it has resulted in a significant and serious ‘backlash’ against child protection (see, e.g. Myers 1994).

While there is little disagreement among stakeholders in the child abuse debate that it is morally wrong for children to be harmed unnecessarily and that children should be protected from the harmful behaviours of others, there is considerable disagreement about the kinds of things that can and should be considered bona fide ‘harmful’ to children, the kinds of acknowledged harms that children ought to be formally protected from, and how best to protect children from the harms deemed both bona fide and unacceptable. Thus, while there may appear to be a social consensus about the moral unacceptability of child abuse, quite the reverse may be true. As Lantos (1995: 45) points out, an apparent consensus about child abuse may, paradoxically, ‘mask profound disagreements’ about the nature of child abuse and the apparent responsibilities of various parties (including parents/guardians, health professionals and government authorities) to intervene. Two poignant examples of this can be found in the tragic Australian child abuse cases respectively of Daniel Valerio and Cody Hutchings.

T he case of Daniel Valerio

On 8 September 1990, Daniel Valerio, a 2-year-old boy living in the State of Victoria, was bashed to death by his stepfather. During the inquest that followed, it was revealed that 21 professionals (including three general medical practitioners, a paediatrician, nurses, social workers, a psychologist, a community health worker, teachers and police) as well as neighbours and family friends had all observed bruising on Daniel Valerio’s body in the months leading up to his death (Farouque 1993a: 3; Garner 1993: 24; Goddard 1996: 174–5). Despite making these observations, no action was taken and, as a result, the child remained in an abusive situation. In July, before his death, Daniel Valerio was admitted to a local hospital for assessment and treatment of a large haematoma on his forehead and other bruises observed on his body, head and limbs. Despite suspicions about the nature of the boy’s injuries, the attending paediatrician, in consultation with a psychologist acting as a social worker at the hospital, ‘decided that there were not sufficient grounds to refer to protective services but that Daniel should be monitored’ (Goddard 1996: 174–5). Later it was also revealed that a family doctor had suspected the child was being abused a week before he died ‘but left it to the boy’s mother — a key suspect — to seek specialist medical advice’ (Farouque 1993b: 3). Upon autopsy, it was found that Daniel Valerio had sustained 104 external injuries, predominantly bruises, on his body (Farouque 1993a: 3; Garner 1993).

The Daniel Valerio case received widespread media attention around Australia and sparked public outrage. A burning question on many people’s lips was: How could this have happened? One commentator has since suggested that a possible reason for why the case ‘happened’ is because the professionals concerned were simply ‘not convinced of the need to act’ (Goddard 1996: 180). It was further contended that had a stranger (rather than a primary caregiver) been suspected of beating the child, ‘the responses of all the systems would have been entirely different’; quite probably the child would have received ‘immediate medical examination and treatment’ and the media would have reported the attack ‘and provided descriptions of the attacker’ (Goddard 1996: 180–1). Instead, Daniel Valerio’s case was met initially with silence and disbelief until it was too late.

T he case of Cody Hutchings

In March 2006, Cody Hutchings, a 5-year-old boy living in the State of Victoria, died after he had been repeatedly beaten with a heavy strap by his mother’s partner (Stuart John McMaster) over an 8-week period (Kissane & Rood 2007). On the day of his death, Cody Hutchings was struck up to 25 times. The campaign of violence that Cody Hutchings was subjected to left him with ‘massive injuries and covered in 160 bruises’ (Whinnett & Roberts 2007: 4).

In 2007, Stuart John McMaster was sentenced to 13 years jail (with a minimum term of 10 years) for the manslaughter of Cody Hutchings. This sentence, deemed by many commentators to be grossly inadequate, sparked community outrage and ‘commendable promises of political action’ (Silvester 2007: 9). In recognition of the inadequacy of the sentence, the Victorian State Government moved quickly and heralded its intention to create a new law ‘specifically for the crime of child killing’ (Whinnett & Roberts 2007: 4). Despite widespread support for the need to recognise ‘child killing’ as murder (not merely manslaughter) (Silvester 2007), response to the government’s proposal was mixed (Kissane & Rood 2007: 5). Critics highlighted the need to also have legislative provisions for ‘failure to protect’ children in abusive situations (Kissane & Rood 2007: 5). As one commentator reflected with reference to the fact that child killings often ended up as ‘manslaughter rather than murder’, with sentence being very low:

When Cody was dying … (McMaster) beat him day after day. I do think that it’s extraordinary that he inflicted so much damage … over such a long period and didn’t receive anything like the maximum. I can’t imagine what anyone would have to do to get the maximum if the repeated brutal assaults on Cody didn’t deserve it.

(Goddard — quoted in Kissane & Rood 2007: 5)

I s the ‘failure of the system’ to blame?

It has been suggested that the ‘failure of the system’ to be convinced of the seriousness of a child’s situation and the need to take protective action rests, in complicated ways, on a prevailing social–cultural ambivalence about violence towards children (Goddard 1996). In support of this claim, it is contended that violence towards children is often viewed, controversially, as being merely ‘discipline’ (and hence socially acceptable) when carried out at the hands of parents/guardians. This is perhaps most evident by the fact that ‘the hitting, punching, kicking or beating’ of children is socially and legally accepted in most countries in the world today and remains a ‘significant phenomenon’ in schools and other institutions (including penal institutions) dealing with young people (WHO 2002b). Although Sweden first outlawed corporal punishment in 1979, and other countries (e.g. Namibia, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Israel) have followed suit (WHO 2002b), and while corporal punishment has been banned in schools in Ethiopia, New Zealand, the Republic of Korea, Thailand and Uganda, currently only 2.4% of the world’s children are ‘legally protected from corporal punishment in all settings’ [emphasis added] (Pinheiro 2006: 12).

In Australia, there has been support at Federal government levels for the use of ‘physical punishment’ of students. The Federal Minister for Education, for example, was reported in 2007 as ‘leaving the door open for a return to physical punishment of students — backing autonomy for school principals to decide on its use’ (Schubert 2007: 1). The Federal Minister for Health was reported as also supporting the idea, stating that while he was not calling ‘for the return of the cane or the strap … there was a case for them’ (Schubert 2007: 1). He was further reported to have argued that ‘a lot of people think that sometimes you’ve got to be able to give [kids] a short, sharp shock’ and ‘it may well be that sometimes the only language that some kids understand is that kind of language’ (Schubert 2007: 1).

There are, however, other possible explanations for why the system is failing. For instance, there is much to suggest that the ‘failure of the system’ to intervene appropriately to protect children rests on something far deeper and more complex than an ambivalence about violence per se towards children. There are other underpinning ambivalences at play, including (and perhaps especially) an extraordinary social–cultural ambivalence about the moral status, moral interests and related moral entitlements of children and the correlative moral responsibilities these entitlements impose on others who come into contact with children (Johnstone 1999b). This ‘moral ambivalence’ has contributed to the ‘failure of the system’, by undermining the confidence of people in taking what Hoff (1982) calls ‘private moral initiative’ and ‘private benevolence’ (read individual moral action) needed to genuinely assist and protect children who are at risk.

If children were genuinely regarded as having moral status and significant moral interests deserving of protection (at least comparable to that otherwise enjoyed by adults), the world’s historical response to child maltreatment and protection may well have been very different. For instance, there may have been less of a tendency both privately and publicly to regard the moral interests of children as being subordinate to the interests of adults (in particular, parents). This, in turn, might have resulted in individuals (including professionals), groups, communities and governments responding more effectively to the problem of child maltreatment and protection than has historically been the case. And it might also have resulted in individuals, groups and communities positioning themselves better to break the cycle of intergenerational violence that has become so characteristic of contemporary societies everywhere. Instead, the problem of child abuse has foundered on a bedrock of moral malaise that, arguably, will not shift until there is a concerted effort at both an individual and collective level to challenge and change the status quo.

T he ethical implications of child abuse

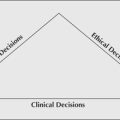

Whether driven by legal obligation or moral commitment, or both, a health care professional’s decision to report child abuse (or not report it, as the case may be) never occurs in a moral vacuum and is never free of moral risk. Even in the face of clinical certainty (insofar as this is possible) and the threat of legal and professional censure for non-compliance with mandatory reporting requirements (insofar as this is probable), there is always room to question: Should I report this particular case of known or suspected child abuse and/or neglect? Underpinning this question are the additional questions of: What are the possible consequences to the child of me reporting or not reporting this case? What are the possible consequences to the child’s family/caregivers of me reporting or not reporting this case? and What are the possible consequences to me of reporting or not reporting this case? Possible answers to these questions will depend, in varying degrees, upon an effective harm/benefit analysis of the situation.

T he moral demand to report child abuse

Child abuse (often used as ‘an “umbrella” term that covers a wide range of activities that harm children in some way’ [Goddard 1996: 28]), can take a number of forms, including physical, sexual, emotional and spiritual. It can also involve neglect, defined here as ‘the failure to provide the child with the basic necessities of life, such as food, clothing, shelter and supervision, to the extent that the child’s health and development are placed at risk’ (Child Protection Victoria 1993: 3). In some instances, all forms of abuse may overlap; for example, a child who is sexually abused is ipso facto abused physically, emotionally and spiritually as well (Renvoize 1993: 36).

Although historically there has been considerable disagreement about how child abuse can and should be defined (Johnstone 1999b; Goddard 1996; O’Hagan 1993), this is not sufficient to threaten strong moral arguments against child abuse and its intervention, as some have suggested (see, e.g. Lantos 1995: 43). Child abuse can be (and, as shown earlier, has been) defined in ways that unequivocally distinguishes it from other ‘acceptable’ behaviours directed at children (e.g. play, discipline, ‘character building’, education) and it is spurious to suggest otherwise. A key feature of child abuse (not carried by other behaviours directed at children) concerns the risk of non-accidental and culpable harm that it poses to a child’s genuine welfare and wellbeing. These risks are not merely speculative or imaginary, but substantive and known through the supportive findings of rigorous research, an increasing body of professional literature on the subject, and, not least, by the survivors of child abuse themselves who are increasingly coming forward to share their experiences by making their ‘stories’ public.

In all its forms, child abuse can cause significant and lasting harm to children and, ultimately, the adults they become. Borrowing from Archard (1993: 150): ‘A child may be harmed both as a child and as a prospective adult. The adult of the future can be harmed by what is now done to the child.’ It is this consequence of harm that makes child abuse and neglect morally objectionable. Understanding this, however, requires at least a rudimentary understanding of the notion of ‘harm’, the way it is linked to human welfare and wellbeing, and why it is morally compelling both not to cause harm and to prevent harm to others.

T he notion of harm and its link with the moral duty to prevent child abuse

As previously considered in Chapter 3 of this text, harm may be taken as involving the invasion, violation, thwarting or ‘setting back’ of a person’s significant welfare interests to the detriment of that person’s wellbeing (Feinberg 1984: 34; Beauchamp & Childress 1994: 193). Wellbeing, in turn, can include interests in:

continuance for a foreseeable interval of one’s life, and the interests in one’s own physical health and vigour, the integrity and normal functioning of one’s body, the absence of absorbing pain and suffering or grotesque disfigurement, minimal intellectual acuity, emotional stability, the absence of groundless anxieties and resentments, the capacity to engage normally in social intercourse and to enjoy and maintain friendships, at least minimal income and financial security, a tolerable social and physical environment, and a certain amount of freedom from interference and coercion.

(Feinberg 1984: 37)

The test for whether a person’s interests and wellbeing have been violated or thwarted rests on ‘whether that interest is in a worse condition than it would otherwise have been in had the invasion not occurred at all’ (Feinberg 1984: 34). For instance, if a person (e.g. a child, a young person or an adult survivor of child abuse) is left psychogenically distressed (e.g. emotionally unstable, anxious, depressed and/or suicidal) as a result of his/her abusive childhood experiences, our reflective commonsense tells us that this person’s interests have been violated and the person him/herself ‘harmed’. As the American philosopher Joel Feinberg (1984) explains, the violation of a person’s welfare interests renders that person ‘very seriously harmed indeed’ since ‘their ultimate aspirations are defeated too’.

P rotecting the interests of children as children and as prospective adults

It is generally recognised in contemporary bioethical thought that people ought not to cause harm to or impose risks of harm onto others. It is also accepted that people have a moral obligation to prevent harm to others if this can be done without sacrificing other important moral interests (Beauchamp & Childress 2001; Singer 1993). By this view, acts which violate the interests of others, or fail to prevent the interests of others being violated, are prima facie morally wrong. The abuse of children — and the failure to prevent it — clearly violates the interests of children (both as children and as prospective adults) and renders them seriously harmed. It is the profound risk of the harmful consequences of child abuse (at all stages of life), and the utter preventability of these consequences, that makes intervention in child abuse at all levels morally compelling. Failure to prevent this harm is morally wrong. Further, the moral unacceptability of child abuse is underscored when it is remembered that the harmful consequences of child abuse do not remain quarantined in a ‘lost and forgotten’ childhood which a person can leave behind upon entering adulthood. As Briere (1992: xvi) points out ‘in the absence of appropriate intervention, hurt children often grow to become distressed and symptomatic adolescents and adults’ — a morally significant and harmful outcome.

What is not always understood in this debate is that the negative effects of child abuse can be long term and sometimes devastating, affecting, in morally significant ways, not only the individuals who survive their traumatic childhoods, but those with whom they share relationships including family, friends, partners, co-workers, service providers and the community at large. Moreover there is now a substantial body of evidence that child abuse is strongly related to major adult illnesses — including ischaemic heart disease, cancers, chronic lung disease, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia and chronic pain syndromes (see, e.g. Briere 1992; Corby 2000; Dong et al 2004; Elliott 1993; Herman 1992; Loring 1994; Mullinar & Hunt 1997; Phillips & Frederick 1995; Porterfield 1993; Renvoize 1993; Rodgers et al 2004; Roy 1998; Terr 1994; Valent 1993; van der Kolk et al 1996; Wilson & Raphael 1993; WHO & ISPCAN 2006). Child abuse has also been strongly implicated in both short-term and long-term mental health problems including depression, anxiety, aggression, shame, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, suicide ideation, personality disorders, cognitive impairment, suicide and a range of psychiatric conditions (Rodgers et al 2004; Romito et al 2003; Roy 1998; WHO 2002b).

Research has also found that the physical and mental health consequences of childhood abuse can manifest in people up to 40 years after the first incident of abuse (Springer et al 2007). In cases of multiple forms of abuse (including psychological abuse, neglect and family dysfunction) the interrelated adverse health effects can be particularly onerous on survivors (Dong et al 2004). This is so, even for those who receive professional help in dealing with their child abuse issues. As one commentator notes:

Day to day, moment to moment, our feelings and perceptions of the world can change. No matter how long you have been ‘working’ on your abuse, or how you may feel that at last you can live your life rather than just exist, there are times when you can be overwhelmed quite unexpectedly with painful feelings and memories of your abuse. The ‘trigger’ can be a smell, a sound, a memory apparently from nowhere. Of this, one survivor says: ‘One day, one moment, you can believe that you are all right, that the world and the people in it are all right, and the next be right back down there in the pit of despair.’

(Longdon 1993: 59)

This ‘reality’ is exemplified by one adult survivor of child abuse, who writes:

The last seven years have been very difficult for me. For nearly two years I was unable to work, simply being traumatised by the memories that kept bombarding me. My ensuing depression put me in a psychiatric hospital for about eight months in total, and during that time I tried to end my life three times by taking overdoses, and continued to self-abuse by slashing myself. It took me eight years to complete a three-year university degree, as I had to keep dropping out when I had breakdowns.

(Mono 1997: 40)

These examples (which stand as just two among many [see others included in Mullinar & Hunt 1997]) show that adult survivors of child abuse can be seriously harmed (have their welfare interests and wellbeing violated) by their traumatic childhood experiences. The survivors quoted in these examples are plagued by painful feelings and memories of their past childhood abuse and, as a result, are thwarted in realising their ultimate aspirations, not least to be free of the ‘absorbing pain and suffering’ and ‘emotional instability’ that has come to characterise and burden their lives. This outcome is morally wrong and ought to have been prevented.

It might be objected here that many survivors of child abuse do not emerge from their traumatic childhood pasts as ‘damaged goods’ (Sanford 1990), do go on to live productive and satisfying lives (which indeed they do [see, e.g. Higgins 1994]), and therefore are no longer ‘harmed’ by their childhood abuse. While many survivors of child abuse do go on to live productive and satisfying lives, this is not sufficient to negate or to override the moral obligation to intervene and prevent child maltreatment. There are at least two reasons for this. First, maltreated children are still harmed as children by their traumatic experiences irrespective of their survival into adulthood. To deny the suffering of children — or at least to render this suffering as irrelevant — is to discriminate against them in morally unjust ways; it seems to be saying that the suffering of children does not count (or, at least, does not count as much as the suffering of adults) just because it is children who are suffering. This ‘adultist’ view is morally indefensible. Second, even if adults who have survived child abuse do go on to live productive and satisfying lives, this is not to say that they do not also suffer in unjustly burdensome ways as a result of their traumatic childhood pasts.

C onsiderations against the mandatory and voluntary notification of child abuse

Public policy requirements to report child abuse have historically been criticised and even rejected by a range of people including members of the medical profession, community support groups and, not least, members of the judiciary (e.g. Family Court judges) (Fogarty 1993; Fogarty & Sargeant 1989; Goddard 1996; MacNair 1992; Mendes 1996; Myers 1994). The grounds for this criticism and rejection have mostly been utilitarian in nature, involving a calculation of harms and benefits to: (1) the professional–client relationship; (2) parents and families of allegedly abused and neglected children; and, lastly (3) allegedly abused and neglected children themselves. Requirements to report child abuse and neglect have also been criticised, controversially, on civil libertarian grounds. Here arguments are advanced to the effect that requirements to report child abuse stand as a fundamental violation of parental rights to be free of state interference and to decide how best to raise their children (Archard 1993). As one commentator observes in relation to the alleged ‘dangers’ of children’s rights discourse, ‘taken literally, respect for children’s rights may permit substantial intrusion into parents’ lives’ (Schrag 1995: 356). These considerations are not unproblematic, however, and are themselves vulnerable to criticism. Consider the following.

T he professional–client relationship

Legitimised requirements to report child abuse and neglect have been viewed as being problematic primarily on grounds that they threaten the sanctity of the professional–client relationship by eroding professional discretion about: (1) duties of confidentiality; and (2) how best to deal with child abuse cases (e.g. by discretional and confidential counselling) (Goddard 1996; Lantos 1995; Lewin 1994; MacNair 1992; Quinn 1992). A related concern has been that legitimised reporting requirements can also shift and extend the boundaries of responsibility of the professional–client relationship; namely, to include not just the adult client but the child client as well. This is seen as potentially creating an intolerable tension between the possibly competing and conflicting interests of all stakeholders in question. For example, it could create for an attending health professional the moral dilemma of how best to uphold the interests of an abused child client without also violating the interests of an abusing adult client, and vice versa. It may well be that, in the end, it is not possible for the health professional to uphold the interests of both clients equally, prompting the question: What should I do?

Consequential to the shift in boundaries of responsibility, there is also a commensurate change in role for the health professional, namely, from that of clinician/healer/therapist to that of ‘statutory protector’. For some, this assumed role of ‘statutory protector’ could further threaten the therapeutic sanctity of the professional client relationship, begging the question of the moral acceptability of health care professionals functioning as the ‘eyes of the state’; that is, as agents of a ‘state surveillance’ system.

P arents and families

Legitimised requirements to report child mistreatment have also been criticised and rejected on grounds that these stand to seriously threaten the ‘liberal rights’ (to privacy and self-determination), welfare interests and wellbeing of parents and families (Archard 1993: 122–32). The risk of this happening is seen to be especially high in the case of false allegations being made, or where health care professionals are either ‘overly zealous’ or incompetent or impaired in performing their assessments of allegedly abused children and reporting their findings to child protection services. For example, health care professionals may be lacking in the necessary skills or may make the wrong judgments or, because of their own unresolved personal issues, are just not able ‘to come to terms fully with any abuse’ (Renvoize 1993: 152). Some critics contend that, in the ultimate analysis, the legitimated reporting of child abuse could result in parents and families being left stigmatised, embarrassed and even irreparably damaged — particularly if the family is ‘totally dismembered through termination of parental rights’ (Giovannoni 1982: 108; Lantos 1995: 44). Parents and families could, therefore, be harmed as a result of interventions by child protection services. This, in turn, could seriously harm the welfare interests and wellbeing of the children suspected of being mistreated by their parents and families, but who nevertheless remain dependent on them for care. In short, harmed parents/families could ipso facto result in harmed children.

A bused and neglected children

Perhaps among the most serious and troubling criticisms of all is the view that legitimated requirements to report child abuse may, paradoxically, cause further harm to abused children themselves (Goddard 1996; Lantos 1995; Lewin 1994; Miller & Weinstock 1987). The ‘harmfulness’ of the intervention, in this instance, is thought to derive from, and be compounded by, a number of processes:

▪ Through children being separated (sometimes prematurely) from their parents/primary caregivers and surrendered to ‘ambiguous substitute family arrangements’ (Giovannoni 1982: 108; Miller & Weinstock 1987: 162).

▪ Where separation and removal damages the child–parent/guardian relationship, not least through ‘interfering with the ability of abusing parents to deal with their problems and reintegrate their families’ (Miller & Weinstock 1987: 162). Further, if protective processes (e.g. court action) are unsuccessful, this could result in an abused child being returned ‘unprotected to an unbelieving family which might scapegoat them and blame them for all the disruption’ (Renvoize 1993: 152).

▪ Where protective services simply fail mistreated children, for example:

• where referrals and protective interventions are handled poorly (investigations may be delayed or be ineffective; children may be returned to violent and abusive homes and thus committed to a life of re-abuse, crime and/or death [Fogarty 1993; MacNair 1992])

• where mechanisms for securing child protection may themselves be traumatic and ‘abusive’ (legal processes [including police involvement and court proceedings] are, for example, characteristically intrusive and ‘adversarial’ in nature; media coverage is characteristically intrusive and can be harmfully ‘exposing’ and adversarial in nature) (Lewin 1994)

• where protective services are inadequate to meet the needs of mistreated children, resulting in increasing numbers of children being drawn into a child protection system that is ‘incapable of caring for them properly’ (e.g. as can occur in the case of a protective system plagued by budgetary constraints) (Fogarty 1993: 7).

Thus, in the final analysis, rather than promoting and protecting the welfare interests and wellbeing of abused and neglected children, mandatory and voluntary reporting requirements might block, thwart, intrude upon, set back, invade and violate these moral entitlements. In short, reporting requirements used as a child protection intervention may ultimately prove to be more harmful than the abuse itself.

R esponding to the criticisms

The question remains, however, of whether legitimated demands to report known and suspected cases of child abuse and neglect do stand to ‘adversely’ affect the nature and boundaries of the professional–client relationship, the ‘deserving’ interests of parents and families (and, it should be added, other abusing adults) and, not least, the interests of mistreated children. And, if so, what the moral implications of this might be. It is to briefly considering these questions that the remainder of this chapter will now turn.

T he problem of maintaining confidentiality

Reporting child abuse, unless consented to by both the abuser and the child (given the child is capable of giving consent), almost always involves a breach of confidentiality and privacy. A key reason health care professionals are reluctant to breach confidentiality concerns a fear that, if abusers cannot rely on or trust professional caregivers to keep secret abuse-related information disclosed in the professional–client relationship, then they (the abusers) may be discouraged from seeking help to remedy their abusive behaviours. In effect, legitimised reporting laws could ‘drive people underground’ (Goddard 1996: 98; MacNair 1992: 129). It is not clear, however, that this fear is sufficient to justify maintaining confidentiality in favour of an abusing adult. There are a number of reasons for this. The first of these concerns the very nature of the moral demand to maintain confidentiality itself.

Traditionally, as discussed in Chapter 6 of this book, the rule of confidentiality has demanded that information gained in the professional–client relationship ought to be kept secret even when its disclosure might serve a greater public good. Over time, however, real-life examples and moral theorising have repeatedly shown that treating the rule of confidentiality as being absolute is morally unjust, indefensible and unreasonable (Bok 1983, 1978). At best, maintaining confidentiality should be treated as only a prima-facie obligation. What this means is that while, as a general rule, confidentiality ought to be maintained in the professional–client relationship, there may sometimes be stronger moral reasons for overriding this obligation. An example here would be where an abusing adult discloses to an attending health care professional his or her intention to deliberately injure a child. A decision to disclose this information in order to warn and protect the intended child victim would be justified on grounds that it could help to prevent an otherwise avoidable harm from occurring.

Superficially, the disclosure of privileged information in the above example might appear to be in breach of a disclosing client’s ‘rights’ to confidentiality. However, confidentiality was never meant to stretch so far as to compel an attending health care professional to lie or to protect those who have no right to impose their malevolence on innocent victims — in this instance an innocent child (Bok 1978: 148). Borrowing from Bok (1978: 155), ‘only an overwhelming blindness to the suffering of those beyond one’s immediate sphere’ could justify the maintenance of absolute confidentiality in the case where innocent others are at risk of being harmed. Further, a client’s moral entitlements to have certain information about themselves kept secret are forfeited where the maintenance of confidentiality about their case stands to seriously impinge on the moral interests and wellbeing of innocent others. In this instance, morally constrained discretionary breaches of confidentiality are morally justified.

In the case of child abuse, there exists strong moral grounds (in addition to mandated legal requirements) for justifiably overriding an obligation of confidentiality that might otherwise be due to an abusing adult, and for discretionary disclosures to be made to appropriate people. In regard to the ‘possible harm’ that discretionary disclosures may cause to abusers (e.g. driving abusers ‘underground’ and discouraging them from seeking help; causing them to feel hurt, embarrassed and stigmatised; dismembering families; and so forth), this is not sufficient to justify the maintenance of absolute confidentiality. One reason for this is: it is not clear that discretionary disclosures will necessarily harm the welfare interests of abusers. The aim of protective interventions (of which the legitimated reporting of child abuse is a form) is to ‘protect children, not to punish abusers’ and to be ‘curative and remedial rather than punitive’ (Corby 2000; Fogarty 1993; Lewin 1994; Miller & Weinstock 1987; Scott & O’Neil 1996). Thus disclosures that are made to appropriate people stand to not only benefit an abused child, but also set in motion a process that could potentially assist the abuser as well. If the abuser is genuinely accepting of responsibility for his or her abusive behaviour towards children and is committed to rehabilitation, then the problem of competing demands to maintain confidentiality can be overcome by the health care provider negotiating the discretionary disclosure of privileged information gained in the professional–client relationship. If, however, an abuser is unwilling to accept responsibility for his or her abusive behaviour and is unwilling to give permission for a discretionary breach of confidentiality to the relevant authorities, the health care professional has an overriding moral obligation (and in some jurisdictions, is legally mandated) to take the action necessary to protect the interests of an at-risk child or children. Discretionary breaches of confidentiality are morally justified in these instances.

T he problem of statutory surveillance

Some claim that legitimised reporting requirements could exacerbate the problem of child abuse in another way; namely, by facilitating its ‘over-reporting’ (including a proliferation of false allegations being made about its incidence) (Goddard 1996: 98; Renvoize 1993; Miller & Weinstock 1987). This, it is contended, might result in ‘more children and families being drawn into a system which does not have the capacity to provide the necessary services to them’ (Fogarty 1993: 12). Furthermore, were health care professionals seen to be spearheading this ‘over-reporting’ through their surveillance role, this could result in a loss of community trust in service providers and, ultimately, ‘the system’ which, in turn, could work against an effective overall societal response to child abuse and neglect.

It is not clear, however, whether community trust in health care professionals would be eroded by a proliferation in the reporting of child abuse. For one thing, a proliferation in the reporting of child abuse may not necessarily be spurious. An increase in reporting could be directly linked to a genuine increase in the actual incidence of abuse which, in turn, can be further linked to increased professional and community awareness of what constitutes child abuse and its unacceptability (Corby 2000; Goddard 1996; Fogarty 1993). Thus, while being perplexed by an increase in the reporting of child abuse, the community might nevertheless be reassured that ‘the system’ is working and that children are being protected from unnecessary harm. Contrary to the claims made above, it might be a failure by health care professionals to report child abuse that risks undermining community confidence in their services, not the reverse. The Daniel Valerio case (cited earlier in this chapter) is an example of this.

P reserving the integrity of the professional–client relationship

Legitimated requirements to report child abuse do not necessarily threaten the sanctity or integrity of the professional–client relationship. If disclosures are handled in a morally, legally and clinically informed, culturally and clinically competent and sensitive manner, this need not involve a collapse of the boundaries between matters of clinical competence and legal and moral prescription/proscription, as some have suggested (Giovannoni 1982: 108). To the contrary. Legal and moral prescriptions/proscriptions in the case of child abuse can strengthen the bases and boundaries of clinical competence by reminding health care professionals to always consider carefully the precise impact that their acts and omissions can have on the lives of others (especially children both as children and as prospective adults), and to remain vigilant in regard to their capacity to harm as well as benefit those in their care.

U pholding the interests of parents, families and abused children

It is fully acknowledged that the act of reporting child mistreatment is one which is fraught with difficulties. It is further acknowledged, there are no guarantees that mistakes will not occur. But the risks of failing to intervene are equally if not more onerous. By not reporting instances of child mistreatment, there is a risk that abused and neglected children will be ‘left forgotten and invisible’ (Mullinar & Hunt 1997) and, without help, will go on to be symptomatic adults. There is an additional risk that, without intervention (whatever the risks), the sequelae of child mistreatment could ‘continue to wreak havoc generation after generation’ (Lord 1997). Appropriate intervention to prevent child abuse (of which reporting may be the first step) can make a significant contribution to breaking the cycle of intergenerational violence.

As suggested earlier, it is not necessarily the case that protective interventions (of which the legitimated reporting of child abuse is a form) will harm the deserving welfare interests of abusing parents and families. It needs to be remembered that a key aim of interventionist strategies is ‘to protect children, not to punish the abusers’, and, where able, to offer dysfunctional adults and families remediation. Thus appropriate interventions stand to not only benefit an abused child, but also to set in motion a process that could potentially assist and benefit abusers as well.

In the case of children, there is no denying that separation from a primary caregiver can be an extremely traumatic experience for a child — even when the primary caregiver is the abuser. While it might be assumed that an abused child would be ‘happy’ to get away from an abusive parent, this is not necessarily so. (There are many complex reasons for this which, regrettably, are beyond the scope of this present work to consider [see, e.g. van der Kolk 1996: 200].) And there is no denying that children can be — and have been — seriously harmed when protective interventions have ‘gone wrong’. It is acknowledged that children can be — and are — seriously harmed when the system fails them. What this instructs, however, is not the abandonment of protective services or components of it (e.g. reporting requirements). Rather, it highlights the need for protective processes to be improved. In summary, attention ought to be focused on improving — not removing — the systematic processes that have been put in place to help protect children from the harms of abuse and neglect.

T he importance of a supportive socio-cultural environment in child abuse prevention

In her classic work Trauma and recovery: the aftermath of violence — from domestic abuse to political terror, the American psychiatrist Judith Herman persuasively argues that (1992: 9):

In the absence of strong political movements for human rights, the active process of bearing witness inevitably gives way to the process of forgetting. Repression, dissociation, and denial are phenomena of social as well as individual consciousness.

Applied in the context of child abuse, there is room to suggest that without a strong political movement for children’s rights, the process of bearing witness (to child mistreatment) will likewise give way to a communal forgetting. The risk of forgetting is particularly great in an environment which is not supportive of nor encourages personal moral initiative and individual acts of benevolence (moral action) aimed at genuinely assisting and protecting children who are at risk.

Herman (1992: 8) contends that ‘without a supportive environment, the bystander usually succumbs to the temptation to look the other way’. Currently, the social and cultural environment in Australia (as well as overseas) is not generally supportive of child abuse prevention and, to some extent, even supports the position of the ‘morally passive bystander’. For many health care professionals located in this unsupportive environment, looking the other way may seem a preferable option to ‘becoming involved’ (Goddard 1996). This ‘not becoming involved’ might even be seen, controversially, as being a morally preferable option on grounds that it could help to avoid the otherwise unpredictable harmful consequences that can (and do sometimes) flow from intervening or becoming involved in a given child abuse/neglect case. What might not be appreciated, however, is that succumbing to the temptation to look the other way and to avoid involvement is not a morally neutral response. Just because health professionals may have done nothing actively to abuse a child (i.e. they may have merely witnessed evidence of possible abuse), this does not mean that they have avoided complicity in the harms to the child caused by his or her initial mistreatment. Borrowing from Joseph Fletcher (1973: 675) writing in another context, ‘Not doing anything is doing something; it is a decision to act every bit as much as deciding for any other deed.’ Thus, a decision to do nothing to intervene in the prevention of child abuse is every bit a decision nevertheless, and still stands as a link in the causal chain of events between an actual instance of abuse and the harm to the child that can and does follow from this abuse.

In their classic report on protective services for children in Victoria, Fogarty and Sargeant conclude that (1989: 52):

basically, the issue [of child abuse] is a public one and one in respect of which each section of the community can and should make a contribution. It would, we feel, be a fundamental mistake to believe that this community problem can be eliminated by a total concentration upon what the government can do for the community. The issue also is — what can the community and individual members of the community do for the state and the children within it? There is too great a tendency both generally and in relation to this particular matter to sit back and demand that the government do this or that but without appreciation of the wider responsibilities which are involved.

There are not, of course, any ‘quick fix’ solutions to the problem of child abuse and protection. But there is considerable scope to suggest that a lot more could be done at an individual, familial, group, community and state level to improve the status quo. Health care professionals have a particularly important role to play on account of them being in a prime position to discern and provide evidence of instances of child abuse and neglect, and to legitimately intervene to prevent these instances from continuing. Through their informed and morally judicious interventions, health care professionals could, in turn, make a significant difference to the lives and welfare interests of both abused children and abusing adults. Legitimated reporting requirements should, therefore, not be seen as an intrusion or a violation of the professional–client relationship, but as an opportunity to provide support and care to injured and distressed human beings (both children and adults alike).

A system of child protection is only as good as the people who are charged with — and who are willing to accept — the responsibilities of upholding it. All health care professionals have an obligation to become sufficiently informed about the clinical, legal, cultural and ethical dimensions of child abuse to enable them to competently participate in child protection and development processes. And there is small doubt that improving the education of health care professionals about child abuse and protection issues will prepare them to deal better with known or suspected child abuse cases. But, as Judith Herman (cited above) makes plain, commitment and education may not be enough; there also needs to be a supportive social environment and a deeply ingrained cultural commitment to preventing the harms of child abuse and neglect across the board.

It is readily acknowledged that ‘child maltreatment is not a simple problem with easy solutions’ (WHO & ISPCAN 2006: 65). Nonetheless, there are a number of strategies that can be implemented at a societal/community, relationship and individual level that would be conducive to the development of a supportive social–cultural environment that is protective of the needs and welfare of children. Notable among the various strategies recommended by global authorities are:

▪ implementing legal reform and human rights

▪ introducing beneficial social and economic policies

▪ changing cultural and social norms

▪ reducing economic inequalities

▪ reducing environmental risk factors

▪ parenting training programs

▪ educating children how to recognise and avoid potentially abusive situations (WHO & ISPCAN 2006: 35).

There has already been a significant move towards adopting a human rights approach to child protection and the prevention of child abuse. In 2006, for example, the UN released the findings of its first ever comprehensive global study on all forms of violence against children. The study is also reputed to be the first UN study ‘to engage directly and consistently with children, underlining and reflecting children’s status as rights holders, and their right to express views on all matters that affect them and have their views given due weight’ (Pinheiro 2006: 3). The release of the UN report is being credited with marking ‘a definitive global turning point’ in terms of the battle to end the justification of violence against children. Through the dedicated work of various international bodies like the WHO, the UN and ISPCAN, there is now a much greater recognition internationally that:

▪ ‘Every child has the right to health and a life free of violence’ (WHO & ISPCAN 2006: 1)

▪ there is a the gap in a human-rights-based commitment to preventing child abuse and investing in prevention policies and programs (WHO & ISPCAN 2006: vii).

Related to the latter point, there is also a much greater appreciation of why the link needs to be made between child maltreatment and human rights, notably that ‘a human rights approach can reinforce and build commitment towards the type of multidisciplinary public health actions that is necessary to prevent violence [against children]’ (WHO 2001b: 7).

In light of these trends, it is perhaps no coincidence that the UN (1989) Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) is, to date, the most widely ratified international human rights treaty and which has ‘set obligations for child protection, prevention of violence, as well as the right to health’ (WHO 2001b: 7).

C onclusion

This chapter has attempted to show that the issue of child maltreatment not only raises a number of important ethical issues, but is itself an important ethical issue. It has also attempted to show that health care professionals have a moral obligation to intervene in the prevention of child abuse and neglect and that this obligation rests on considerations of the welfare interests and wellbeing of children. And while it is acknowledged that the act of reporting child abuse and neglect is one which is fraught with difficulties, the risks of not reporting are equally if not more onerous — not just to abused children but to the community as a whole. In the ultimate analysis, and in support of Fogarty and Sargeant (1989) cited above, ‘each section of the community [including and perhaps especially health care professionals] can and should make a contribution’.

Children should not have to bear ‘silent and unacknowledged witness to their own suffering in many ways throughout their lives’ (Valent 1993: 4). Everyone has a moral responsibility (irrespective of legal law) to break the culture of silence that surrounds child abuse and which has been so effective in invalidating, marginalising and rendering as invisible its untoward effects. Unless this responsibility is accepted and acted upon at an individual and private level, children will remain at risk of the otherwise avoidable harms caused by child abuse and neglect. To fail in this responsibility is not only to fail the most vulnerable members of our society (children), but to fail ourselves and the community as a whole in which we share membership.

Child abuse does not only affect children, it affects us all. It is, therefore, up to each and every one of us (as co-participating members of a moral community) to do what we can in order to prevent it and the harms that flow insidiously from it. Preventing the harms of child abuse is not merely a charitable cause which people can choose to either support or not support. Rather it is an obligation supported by the deepest of ethical considerations and which is binding on all of us. The ultimate question, then, is not one of whether we ought to intervene in the prevention of child abuse, but how we may better intervene and achieve the desired moral outcomes of this intervention.

Case scenario 11

You are a registered nurse working in a paediatric unit. You have been assigned to care for a 12-year-old girl by the name of Christine who has been admitted for observations and investigation of a recent and severe bout of undifferentiated abdominal pain. Shortly after Christine’s admission, while assisting her to have a shower, you notice bruising on her arms and back. After asking her gentle probing questions, Christine confides in you that her mother beats her regularly. She further confides that the bruises on her arms and back are the result of a particularly vicious beating her mother had given her recently using a wooden coat hanger. She also discloses that some weeks earlier she had taken an overdose of aspirin to ‘try and make her mother stop beating her’, but that all her mother had done at the time was to laugh at her and tell her ‘how stupid she was’ and sent her to her room to ‘sleep it off’. Christine then begs you not to tell anyone, pleading, ‘If my mother finds out that I’ve told anyone, she will beat me up. It will be much worse for me.’

Concerned for Christine’s wellbeing and mindful of your statutory duty to report known or suspected cases of child abuse, you decide to seek advice from Christine’s consultant paediatrician. On doing so, the paediatrician tells you: ‘Christine is my patient, not yours. You are not to take this matter any further.’

Case scenario 2

You are working in a paediatric ward where two toddlers (who are sisters) have been hospitalised with extensive bruising to the face and head after being beaten by their mother’s de facto partner. One of the toddler’s face is so swollen, she cannot see. Both the mother and her partner are known drug users, who tested positive for amphetamines and opiates after the birth of their last child just 6 months ago. You also know that the mother’s partner has been convicted and jailed on three separate occasions for assaulting both the toddlers who have just been hospitalised as well as another toddler from another relationship. When the mother of the toddlers visit, you notice that the toddler’s 6-month-old brother is pale and has what looks like a bruise on his face — although you are not sure. Meanwhile, the toddlers’ grandmother (who has been visiting out of hours in order to avoid contact with her daughter), begs you to make sure that the toddlers ‘are not sent back to their parents’ home environment’. She expresses her deepest fear that ‘if the kids are sent back home something very terrible is going to happen to them’. She also confides in you that she is deeply worried about the other baby, who she suspects is also being beaten by her daughter’s partner. The toddlers gradually recover from their injuries and are ready to be discharged from hospital. Despite having reported the grandmother’s concerns to the health care team, you are shocked to learn that the government department responsible for child protection has approved that the toddlers be discharged back to their parents’ home environment, advising hospital staff that ‘the environment is conducive for their [the toddlers’] return to their parents’.

CRITICAL QUESTIONS

1. What are your moral and legal responsibilities in these cases?

2. In regard to the first case scenario, are you obliged to uphold Christine’s request for confidentiality to be maintained? And, are you obliged to honour the paediatrician’s directive in this case?

3. In regard to the second case scenario, are you obliged to accept the department’s position, or to take the matter further?

4. What actions should you take?

Endnote