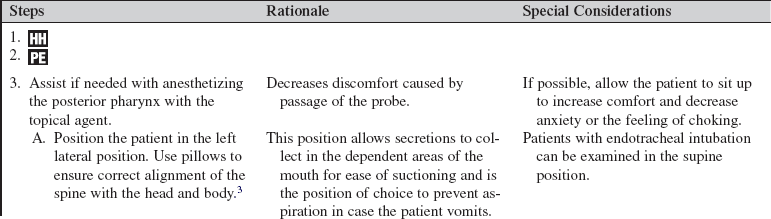

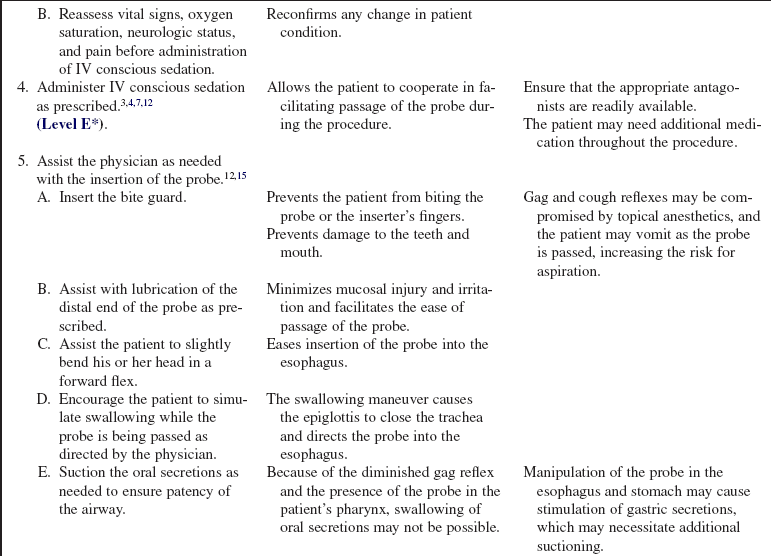

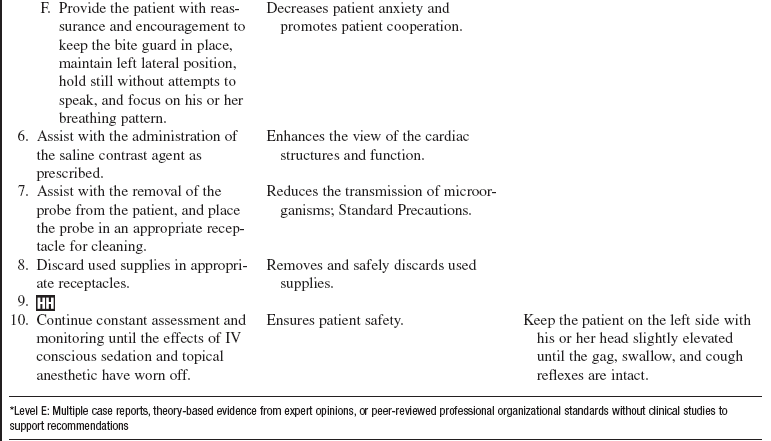

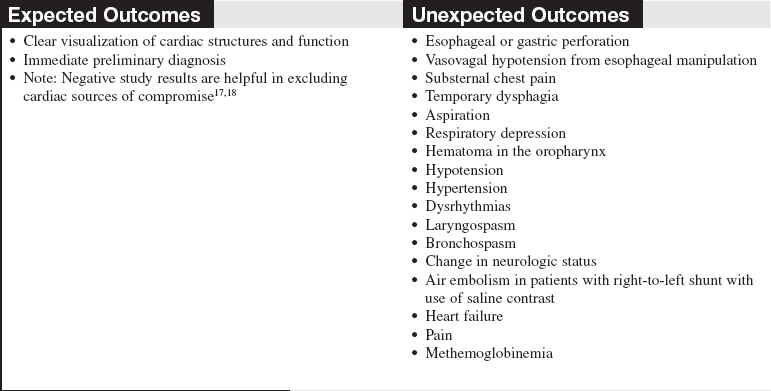

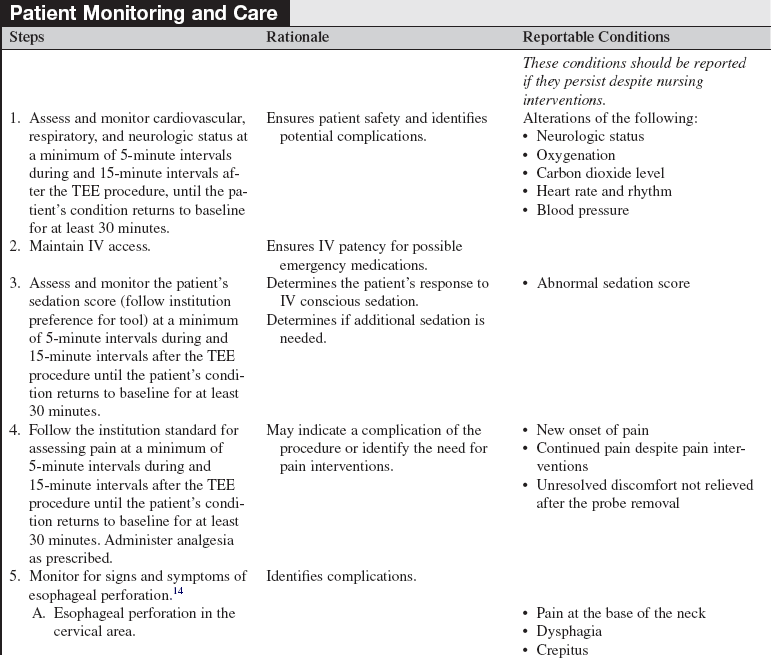

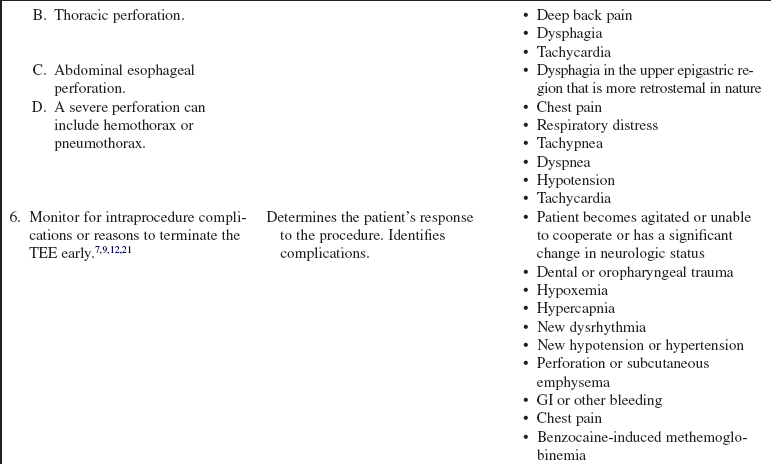

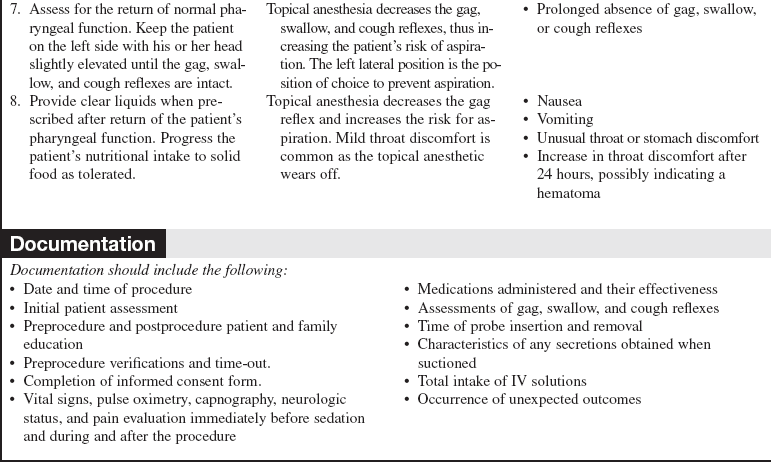

Transesophageal Echocardiography (Assist)

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Knowledge of cardiovascular anatomy and physiology is necessary.

• Knowledge of basic dysrhythmia recognition and treatment of life-threatening dysrhythmias is needed.

• Advanced cardiac life support knowledge and skills are necessary.

• A topical anesthetic is used in the oropharyngeal area; thus, the patient’s gag reflex may be diminished or absent, putting the patient at risk for aspiration.12,15

• It is essential to understand the institution’s intravenous (IV) conscious sedation guideline.

• Sedation can put the patient at risk for respiratory depression.3,5,15

• A fiberoptic probe with an ultrasound transducer is inserted through the mouth and into the esophagus just behind the heart (Fig. 79-1). The transducer located at the tip of the probe sends high-frequency sound waves toward the heart, which return as echoes. The echoes are converted, by computer, into moving images of the heart. The image is displayed on a screen and can be recorded on videotape or compact disk (CD), printed on paper, or sent electronically to a picture archiving communication system (PACS). This test is used to visualize structures of the heart and aorta that may not be seen with a standard transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) and to clarify structures, that may be otherwise poorly seen. The test may be performed as an outpatient or inpatient procedure or in the operating room.3,16,18

• Various modes of echocardiography are used to examine the heart, blood vessels, valve function, and blood flow. The three techniques are as follows17:

Motion-mode (M-mode) echocardiography: This is a one-dimensional echocardiogram that visualizes time, depth, and intensity. It looks like a tracing instead of a picture of the heart and is used to measure the exact size of the heart chambers.

Motion-mode (M-mode) echocardiography: This is a one-dimensional echocardiogram that visualizes time, depth, and intensity. It looks like a tracing instead of a picture of the heart and is used to measure the exact size of the heart chambers.

Two-dimensional (2-D) echocardiography: This shows the actual shape and motion of the different heart structures. These images represent “slices” of the heart in motion.

Two-dimensional (2-D) echocardiography: This shows the actual shape and motion of the different heart structures. These images represent “slices” of the heart in motion.

Doppler echocardiography: This assesses the flow of blood through the heart. The signals that represent blood flow are displayed as a series of black-and-white tracings or color images on the screen.

Doppler echocardiography: This assesses the flow of blood through the heart. The signals that represent blood flow are displayed as a series of black-and-white tracings or color images on the screen.

• Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) imaging is more risky than transthoracic imaging because of the insertion of the probe in the esophagus and the need for IV conscious sedation.4,16

• Indications for TEE are as follows:

Evaluation of (pre) clot formation in the heart, especially in the atria and appendages, in patients with an atrial dysrhythmia.3,6,15,18,20

Evaluation of (pre) clot formation in the heart, especially in the atria and appendages, in patients with an atrial dysrhythmia.3,6,15,18,20

Evaluation of spontaneous echocardiographic contrast or “smoke” presenting as dynamic echoes within the left atrium and appendage, which resembles swirling smoke in 2-D images. It is manifested by erythrocyte and platelet aggregates in regions of low blood flow; it has a significant correlation with previous embolic events and may serve as a marker for increased risk for embolism.3,6,15,18,20

Evaluation of spontaneous echocardiographic contrast or “smoke” presenting as dynamic echoes within the left atrium and appendage, which resembles swirling smoke in 2-D images. It is manifested by erythrocyte and platelet aggregates in regions of low blood flow; it has a significant correlation with previous embolic events and may serve as a marker for increased risk for embolism.3,6,15,18,20

TEE before cardioversion is advocated in patients in whom early cardioversion would be clinically beneficial. Patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing electrical cardioversion with short-term anticoagulation therapy have lower hemorrhagic complications. Cardioversion may be performed more safely, after only a short period of anticoagulant therapy, in patients without atrial cavity or appendage thrombus. with TEE. Cardioversion is delayed in patients at high risk with thrombus detected by TEE. Conventional treatment has been to give patients undergoing elective cardioversion therapeutic anticoagulation therapy for 3 weeks before and 4 weeks after cardioversion, to decrease the risk for thromboembolism.11,12,16

TEE before cardioversion is advocated in patients in whom early cardioversion would be clinically beneficial. Patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing electrical cardioversion with short-term anticoagulation therapy have lower hemorrhagic complications. Cardioversion may be performed more safely, after only a short period of anticoagulant therapy, in patients without atrial cavity or appendage thrombus. with TEE. Cardioversion is delayed in patients at high risk with thrombus detected by TEE. Conventional treatment has been to give patients undergoing elective cardioversion therapeutic anticoagulation therapy for 3 weeks before and 4 weeks after cardioversion, to decrease the risk for thromboembolism.11,12,16

Transient ischemic attack or stroke evaluation to rule out cardiac source of emboli and structure abnormalities (e.g., patent foramen ovale) or other abnormalities not identified before a neurologic event.3,15,16

Transient ischemic attack or stroke evaluation to rule out cardiac source of emboli and structure abnormalities (e.g., patent foramen ovale) or other abnormalities not identified before a neurologic event.3,15,16

Multiple factors may obstruct the penetration of the ultrasound beams from the transthoracic approach. Poor-quality TTE images can be found in patients with obesity, chronic obstructive lung disease, chest wall deformities, multiple chest trauma, and thick surgical chest dressings.3,15

Multiple factors may obstruct the penetration of the ultrasound beams from the transthoracic approach. Poor-quality TTE images can be found in patients with obesity, chronic obstructive lung disease, chest wall deformities, multiple chest trauma, and thick surgical chest dressings.3,15

Assessment of native cardiac valve defects, particularly of the mitral valve.1–3,15

Assessment of native cardiac valve defects, particularly of the mitral valve.1–3,15

Assessment of prosthetic cardiac valve function.3,15,16,18

Assessment of prosthetic cardiac valve function.3,15,16,18

Assessment of intracardiac foreign bodies, tumors, or masses.3,15,16,18

Assessment of intracardiac foreign bodies, tumors, or masses.3,15,16,18

Assessment of vegetative endocarditis and abscess.3,8,15,16

Assessment of vegetative endocarditis and abscess.3,8,15,16

Assessment of congenital heart defects.3,15,16,18

Assessment of congenital heart defects.3,15,16,18

The superior sensitivity and specificity of TEE for aortic disease, including aneurysm, dissection, atherosclerosis, mobile plaque, congenital aortic disease, pseudoaneurysm, and traumatic aortic disruption, make it the test of choice in many clinical situations.3,15,16,18

The superior sensitivity and specificity of TEE for aortic disease, including aneurysm, dissection, atherosclerosis, mobile plaque, congenital aortic disease, pseudoaneurysm, and traumatic aortic disruption, make it the test of choice in many clinical situations.3,15,16,18

Disease in the ascending and transverse aorta often necessitates a TEE for complete evaluation; however, a short portion of the distal ascending aorta and proximal transverse arch is usually not visible. This portion is a blind area because of the carina passing between the aorta and the esophagus.3,15,16,18

Disease in the ascending and transverse aorta often necessitates a TEE for complete evaluation; however, a short portion of the distal ascending aorta and proximal transverse arch is usually not visible. This portion is a blind area because of the carina passing between the aorta and the esophagus.3,15,16,18

TEE used in combination with stress test for the evaluation of patients with coronary artery disease. Transesophageal echocardiography–dobutamine stress echocardiography (TEE-DSE) has been reported to be highly accurate for detection of ischemia in patients with suspected coronary artery disease.19

TEE used in combination with stress test for the evaluation of patients with coronary artery disease. Transesophageal echocardiography–dobutamine stress echocardiography (TEE-DSE) has been reported to be highly accurate for detection of ischemia in patients with suspected coronary artery disease.19

Transesophageal atrial pacing stress echocardiography (TAPSE) is an efficient alternative to DSE for the detection of coronary artery disease. The heart rate can be rapidly increased, resulting in myocardial ischemia in regions supplied by stenosed coronary arteries. In contrast to TEE-DSE, termination of pacing results in nearly instantaneous restoration of the patient’s intrinsic heart rate.10

Transesophageal atrial pacing stress echocardiography (TAPSE) is an efficient alternative to DSE for the detection of coronary artery disease. The heart rate can be rapidly increased, resulting in myocardial ischemia in regions supplied by stenosed coronary arteries. In contrast to TEE-DSE, termination of pacing results in nearly instantaneous restoration of the patient’s intrinsic heart rate.10

Intraoperative guide to left ventricular function and intracardiac blood flow and evaluation of cardiac surgical repair.13

Intraoperative guide to left ventricular function and intracardiac blood flow and evaluation of cardiac surgical repair.13

Assessment of a donor heart for transplant.18

Assessment of a donor heart for transplant.18

Intracardiac shunt evaluation. Right-sided echocardiography saline contrast studies are performed to document an atrial septal defect or a patent foramen ovale and to increase the signal strength of the tricuspid regurgitant jet to allow a more accurate estimate of pulmonary artery pressures.18 Saline contrast for TEE is an IV injection of microbubbles formed by agitating a saline solution. This saline contrast results in a marked increase in echogenicity of the right-sided cardiac chambers.22

Intracardiac shunt evaluation. Right-sided echocardiography saline contrast studies are performed to document an atrial septal defect or a patent foramen ovale and to increase the signal strength of the tricuspid regurgitant jet to allow a more accurate estimate of pulmonary artery pressures.18 Saline contrast for TEE is an IV injection of microbubbles formed by agitating a saline solution. This saline contrast results in a marked increase in echogenicity of the right-sided cardiac chambers.22

Cardiac assessment in the interventional laboratory during percutaneous interventions, such as transcatheter closure for atrial septal defects and ventricular septal defects.16,18

Cardiac assessment in the interventional laboratory during percutaneous interventions, such as transcatheter closure for atrial septal defects and ventricular septal defects.16,18

Cardiac assessment during interventional procedures, such as balloon mitral valvuoplasty, nonsurgical reduction of the ventricular septum in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and transseptal catheterization for placement of a catheter during radiofrequeny ablation of cardiac dysrythmias.16,18

Cardiac assessment during interventional procedures, such as balloon mitral valvuoplasty, nonsurgical reduction of the ventricular septum in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and transseptal catheterization for placement of a catheter during radiofrequeny ablation of cardiac dysrythmias.16,18

Cardiac evaluation of left ventricular assist devices for optimal device performance, evaluation of hypoxemia, correct positioning of the cannula to optimize left ventricular filling, and determination of the patient’s ability to be weaned from the mechanical device.16,18

Cardiac evaluation of left ventricular assist devices for optimal device performance, evaluation of hypoxemia, correct positioning of the cannula to optimize left ventricular filling, and determination of the patient’s ability to be weaned from the mechanical device.16,18

Assessment of the critically ill patient as an alternative for the technically limited TTE study.

Assessment of the critically ill patient as an alternative for the technically limited TTE study.

Assessment of unexplained hypotension, volume status, suspected massive pulmonary embolism, unexplained hypoxemia, and complications of cardiothoracic surgery.17,18

Assessment of unexplained hypotension, volume status, suspected massive pulmonary embolism, unexplained hypoxemia, and complications of cardiothoracic surgery.17,18

• Contraindications to TEE can be divided into absolute and relative.

• Absolute contraindications are3,12,18:

Tumor of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract

Tumor of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract

Esophageal obstruction, stenosis, fistulae, or varices

Esophageal obstruction, stenosis, fistulae, or varices

A history of esophageal radiation or unresolved esophageal dilation

A history of esophageal radiation or unresolved esophageal dilation

Gastric volvulus or perforation

Gastric volvulus or perforation

• Relative contraindications are13:

• Antibiotics are no longer administered before the procedure in patients with a prosthetic valve. Echocardiography does not pose a risk for infection.23

EQUIPMENT

• Omniplane transesophageal probe

• Echocardiography machine (compatible with the probe)

• Constant low wall suction with connecting tubing and rigid pharyngeal suction tip catheter

• Water-soluble lubricant (institution-specific)

• Oxygen with both nasal prongs and mask available

• Topical anesthetic such as 2% or 4% lidocaine solution with an administration device (i.e., mucosal atomization device), 2% viscous lidocaine, or benzocaine spray (institution-specific)

• Premedications for sedation and appropriate reversal agents (as prescribed)

• IV insertion kit and IV setup with solution (usually 0.9% normal saline [NS] solution)

• Three-way stopcock and syringes for saline contrast injection (at least two 10-mL syringes with normal saline flush solution)

• Syringes for sedation medications (at least one 5-mL and one 10-mL)

• Tonsillar forceps and cotton balls with radiopaque string attached (institution-specific)

• Flashlight (to assess the oropharyngeal area, especially in the case of trauma)

• Disposable bite guard (may use the type with or without a strap to hold it in place)

• Continuous electrocardiographic (ECG) monitoring

• Continuous oximetric monitoring

• Automatic blood pressure cuff (with manual blood pressure cuff available for backup use)

• Pillow (to support/position neck when the patient lies on the left side during the procedure)

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the procedure and the indication for therapy and the patient’s role in the procedure.  Rationale: Information about the procedure increases patient cooperation and decreases patient and family anxiety and apprehension.

Rationale: Information about the procedure increases patient cooperation and decreases patient and family anxiety and apprehension.

• Ensure that the patient understands the preparation for the procedure, which includes nothing by mouth (NPO) after midnight, or a minimum of 6 to 8 hours. Before the test, the patient may take daily medications, with a sip of water, as prescribed by the physician.3,12  Rationale: Undigested material in the stomach increases the risk for aspiration. Missing a daily medication dose may not be advisable.

Rationale: Undigested material in the stomach increases the risk for aspiration. Missing a daily medication dose may not be advisable.

• Explain to the patient that the local anesthetic may make the tongue and throat feel swollen and that he or she may feel unable to swallow. The gag reflex will be inhibited by the local anesthetic and may last approximately 1 hour after administration. The patient may experience gagging or retching during the numbing process and during the initial passage of the probe.  Rationale: The explanation may assist in decreasing patient anxiety during the procedure.

Rationale: The explanation may assist in decreasing patient anxiety during the procedure.

• Explain that the patient will be sedated to decrease anxiety, to increase comfort, and for ease in passing the probe.  Rationale: This information may decrease patient and family anxiety.

Rationale: This information may decrease patient and family anxiety.

• Explain that the patient will be monitored closely during and after the procedure.  Rationale: The explanation assists in decreasing the patient and family anxiety.

Rationale: The explanation assists in decreasing the patient and family anxiety.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Confirm medications the patient has taken within the last 4 hours.  Rationale: Recent sedative, analgesic, and vasoactive medications may affect the patient’s tolerance and response to the medications given during the procedure.

Rationale: Recent sedative, analgesic, and vasoactive medications may affect the patient’s tolerance and response to the medications given during the procedure.

• Assess the patient’s baseline cardiac rhythm.  Rationale: The patient’s rhythm may have converted if the indication for the procedure was a dysrhythmia. Passage of a large-bore tube may cause vagal stimulation and bradydysrhythmias.

Rationale: The patient’s rhythm may have converted if the indication for the procedure was a dysrhythmia. Passage of a large-bore tube may cause vagal stimulation and bradydysrhythmias.

• Assess the patient’s baseline respiratory, hemodynamic, and neurologic assessment before anesthetizing the posterior pharynx and administering any sedative agents.  Rationale: Baseline assessment data provide information to use as a comparison for further assessment once medications have been administered.

Rationale: Baseline assessment data provide information to use as a comparison for further assessment once medications have been administered.

• Assess the patient’s baseline vital signs, oxygen saturation, and if applicable, carbon dioxide level.  Rationale: Close monitoring of vital signs and oxygenation during the procedure and comparison with baseline are essential to assess the patient’s tolerance of the procedure.

Rationale: Close monitoring of vital signs and oxygenation during the procedure and comparison with baseline are essential to assess the patient’s tolerance of the procedure.

• Assess the patient’s baseline pain characteristic, site, and severity.  Rationale: Baseline assessment data provide information to use as a comparison during and after the procedure.

Rationale: Baseline assessment data provide information to use as a comparison during and after the procedure.

• Assess the patient for a history of substance use.  Rationale: Substance use may affect the patient’s tolerance and response to the medications given during the procedure.

Rationale: Substance use may affect the patient’s tolerance and response to the medications given during the procedure.

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that the patient and family understand preprocedural teaching. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced. Patient and family anxiety is decreased.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced. Patient and family anxiety is decreased.

• Ensure that informed consent has been obtained.  Rationale: Informed consent is necessary before invasive procedures and the administration of conscious sedation. Informed consent protects the rights of the patient and makes a competent decision possible for the patient; however, in emergency circumstances, time may not allow the form to be signed.

Rationale: Informed consent is necessary before invasive procedures and the administration of conscious sedation. Informed consent protects the rights of the patient and makes a competent decision possible for the patient; however, in emergency circumstances, time may not allow the form to be signed.

• Perform a pre-procedure verification and time out, if non-emergent.  Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

• Ensure that the patient has not eaten for at least 6 to 8 hours before the procedure.  Rationale: Undigested material in the stomach increases the risk for aspiration.

Rationale: Undigested material in the stomach increases the risk for aspiration.

• Instruct the patient to void before the procedure.  Rationale: Voiding before the procedure minimizes disruption of the examination.

Rationale: Voiding before the procedure minimizes disruption of the examination.

• Initiate or continue ECG monitoring, apply an automatic blood pressure cuff, and initiate oxygen saturation monitoring and if prescribed, capnography.  Rationale: These measures allow for close cardiovascular and respiratory monitoring during the procedure. Follow institution standard regarding capnography monitoring.

Rationale: These measures allow for close cardiovascular and respiratory monitoring during the procedure. Follow institution standard regarding capnography monitoring.

• Ensure the IV access is in place and functional.  Rationale: IV access is needed to administer premedications and for possible emergency medications.

Rationale: IV access is needed to administer premedications and for possible emergency medications.

• Maintain IV infusion during the procedure.  Rationale: IV infusion maintenance ensures the IV is functioning and available should an emergency situation arise.

Rationale: IV infusion maintenance ensures the IV is functioning and available should an emergency situation arise.

• Have the patient remove any dentures or dental prostheses.  Rationale: Dentures may interfere with the safe passage of the transesophageal probe.

Rationale: Dentures may interfere with the safe passage of the transesophageal probe.

• Set up the suction system with the connecting tubing and a rigid pharyngeal suction tip attached and ready for use.  Rationale: This setup is necessary for suctioning the patient’s oral secretions during the procedure.

Rationale: This setup is necessary for suctioning the patient’s oral secretions during the procedure.

• Administer a small amount of supplemental oxygen if prescribed.  Rationale: Administration of oxygen may maintain adequate patient oxygenation during the procedure.

Rationale: Administration of oxygen may maintain adequate patient oxygenation during the procedure.

• Have a sedative (e.g., midazolam, diazepam) or analgesic (e.g., morphine sulfate, fentanyl) available (as prescribed) and administer when requested. Naloxone and flumazenil must be available for narcotic or sedative reversal.  Rationale: Sedatives and analgesics reduce patient anxiety, promote comfort, facilitate cooperation during the procedure, and decrease myocardial workload.

Rationale: Sedatives and analgesics reduce patient anxiety, promote comfort, facilitate cooperation during the procedure, and decrease myocardial workload.

• Have atropine available at the bedside.  Rationale: Atropine is necessary if a vagal reaction occurs with the insertion and passage of the transesophageal probe.

Rationale: Atropine is necessary if a vagal reaction occurs with the insertion and passage of the transesophageal probe.

• Have the saline contrast agent available if prescribed.  Rationale: The contrast agent enhances the ability to evaluate cardiac structures and function.

Rationale: The contrast agent enhances the ability to evaluate cardiac structures and function.

References

1. de Waroux JB, Pouleur, AC, Goffinet, C, et al, Functional anatomy of aortic regurgitation. accuracy, prediction -of surgical repairability, and outcome implications of transesophageal echocardiography. Circulation 2007; 116:-264–269.

2. Duran, CM, TEE. the ‘roadmap’ for mitral valve repair. J Heart Valve Dis 2006; 15:521–523.

![]() 3. Feigenbaum, H, Armstrong, WF, Thomas, R. Feigenbaum’s echocardiography. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004.

3. Feigenbaum, H, Armstrong, WF, Thomas, R. Feigenbaum’s echocardiography. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004.

![]() 4. Ferson, D, Thakar, D, Swafford, J, et al, Use of deep intravenous sedation with propofol and the laryngeal mask airway during transesophageal echocardiography. J Cardiothoracic Vasc Anesth 2003; 17:443–446.

4. Ferson, D, Thakar, D, Swafford, J, et al, Use of deep intravenous sedation with propofol and the laryngeal mask airway during transesophageal echocardiography. J Cardiothoracic Vasc Anesth 2003; 17:443–446.

![]() 5. Fu, ES, Downs, JB, Schweiger, JW, et al. Supplemental oxygen impairs detection of hypoventilation by pulse oximetry. Chest. 2004; 126:1552–1558.

5. Fu, ES, Downs, JB, Schweiger, JW, et al. Supplemental oxygen impairs detection of hypoventilation by pulse oximetry. Chest. 2004; 126:1552–1558.

6. Fuster, V, Ryden, LE, et al, ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation. a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation)developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2006; 114(7):e257–354.

7. Green, SM. Research advances in procedural sedation and analgesia. Ann Emerg Med. 2007; 49:31–36.

![]() 8. Harris, KM, Li, DY, L’Ecuyer, P, et al. The prospective role of transesophageal echocardiography in the diagnosis and management of patients with suspected infective endocarditis. Echocardiography. 2003; 20:57–62.

8. Harris, KM, Li, DY, L’Ecuyer, P, et al. The prospective role of transesophageal echocardiography in the diagnosis and management of patients with suspected infective endocarditis. Echocardiography. 2003; 20:57–62.

9. Kane, GC, Hoehn, SM, Behrenbeck, TR, et al, Benzocaine-induced methemoglobinemia based on the Mayo Clinic experience from 28,478 transesophageal echocardiograms. incidence, outcomes, and predisposing factors. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167:1977–1982.

10. Kobal, SL, Pollick, C, Atar, S, et al, Stress echocardiography in octogenarians. transesophageal atrial pacing is accurate, safe, and well tolerated. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2006; 19:1012–1016.

11. Maltagliati, A, Galli, CA, Tamborini, G, et al. Usefulness of transoesophageal echocardiography before cardioversion in patients with atrial fibrillation and different anticoagulant regimens. Heart. 2006; 92:933–938.

12. Marchiondo, K, Transesophageal imaging and interventions. nursing implications. Crit Care Nurse 2007; 27 :25–32.

13. Marymont, J, Murphy, GS, Intraoperative monitoring with transesophageal echocardiography. indications, risks, and training. Anesthesiol Clin 2006; 24:737–753.

Min, JK, Spencer, KT, Furlong, KT, et al, Clinical features of complications from transesophageal echocardiography. a single-center case series of 10,000 consecutive examinations. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2005; 18:925–929.

15. Oh, JK, Seward, JB, Tajik, AJ. The echo manual. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

![]() 16. Peterson, GE, Brickner, ME, Reimold, SC, Transesophageal echocardiography. clinical indications and applications. Circulation 2003; 107:2398–2402.

16. Peterson, GE, Brickner, ME, Reimold, SC, Transesophageal echocardiography. clinical indications and applications. Circulation 2003; 107:2398–2402.

![]() 17. Rose, DD. Transesophageal echocardiography as an alternative for the assessment of the trauma and critical care patient. AANA J. 2003; 71:223–228.

17. Rose, DD. Transesophageal echocardiography as an alternative for the assessment of the trauma and critical care patient. AANA J. 2003; 71:223–228.

Sengupta, PP, Khandheria, BK. Transoesophageal echocardiography. Heart. 2005; 91:541–547.

![]() 19. Siddiqui, TS, Stoddard, MF. Safety of dobutamine stress transesophageal echocardiography in obese patients for evaluation of potential ischemic heart disease. Echocardiography. 2004; 21:603–608.

19. Siddiqui, TS, Stoddard, MF. Safety of dobutamine stress transesophageal echocardiography in obese patients for evaluation of potential ischemic heart disease. Echocardiography. 2004; 21:603–608.

![]() 20. Singer, DE, Albers, GW, Dalen, JE, et al, Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy . Chest. 2004; 126(3):429S–456S.

20. Singer, DE, Albers, GW, Dalen, JE, et al, Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy . Chest. 2004; 126(3):429S–456S.

![]() 21. Soto, RG, Fu, ES, Vila, H, Jr., et al, Capnography accurately detects apnea during monitored anesthesia care. Anesth Analg . 2004; 99:379–382.

21. Soto, RG, Fu, ES, Vila, H, Jr., et al, Capnography accurately detects apnea during monitored anesthesia care. Anesth Analg . 2004; 99:379–382.

22. Trevelyan, J, Steeds, RP. Comparison of transthoracic echocardiography with harmonic imaging with transoesophageal echocardiography for the diagnosis of patent foramen ovale. Postgrad Med J. 2006; 82:613–614.

23. Wilson, W, Taubert, K A, Gewitz M, et al, American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group . Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2007; 116(15):1736–1754.

Ball, M. SGNA position statement. statement on the use of sedation and analgesia in the gastrointestinal endoscopy setting. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2003; 26(5):201–209.

Gilman, G, Nelson, JM, Murphy, AT, et al. The role of the nurse in clinical echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005; 18(7):773–777.

Hashimoto, S, Nakatani, S, Tanimura, M, et al. Usefulness of conscious sedation with midazoram during transesophageal echocardiographic examination. J Cardiol. 2004; 44(5):195–200.

Hoole, SP, Falter, F. Evaluation of hypoxemic patients with transesophageal echocardiography. Crit Care Med. 2007; 35(8 Suppl):S408–S413.

Jiminez, MA, Polena, S, Coplan, NL, et al. Methemoglobinemia and transesophageal echo. Proceed Western Pharmacol Soc. 2007; 50:134–135.

Mart CR, Parrish, M, Rosen, KL. Safety and efficacy of sedation with propofol for transoesophageal echocardiography in children in an outpatient setting. Cardiol Young. 2006; 16(2):152–156.

Miyake, M, Izumi, C, Takahashi, S, et al. Efficacy of transesophageal echocardiography in patients with cardiac arrest or shock. J Cardiol. 2004; 44(5):189–194.

Pino, RM. The nature of anesthesia and procedural sedation outside of the operating room. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2007; 20(4):347–351.

Porembka, DT. Importance of transesophageal echocardiography in the critically ill and injured patient. Crit Care Med. 2007; 35(8 Suppl):S414–S430.

Subramaniam, B, Talmor, D. Echocardiography for management of hypotension in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2007; 35(8 Suppl):S401–S407.