CHAPTER 79 Stroke

OVERVIEW

Definition

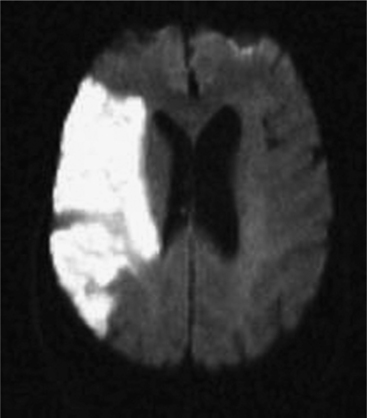

An understanding of stroke is important for psychiatrists for several reasons: it is common, effective treatment is predicated on early recognition, and significant neuropsychiatric sequelae often result from injury to brain parenchyma. Stroke is defined as the acute onset of a neurological deficit due to a cerebrovascular cause. Strokes may be categorized as ischemic (in which the deficit is caused by blockage of an arterial feeding vessel, which results in a lack of oxygen and metabolic nutrients to the affected territory [Figure 79-1]) or hemorrhagic (in which the deficit is caused by vessel rupture). Ischemic strokes occur roughly four times as often as hemorrhagic strokes. Ischemic strokes usually produce focal neurological deficits due to the cessation of blood flow to a specific territory of the brain. In contrast, hemorrhagic strokes, in addition to causing focal deficits, can cause more diffuse symptoms as a result of cerebral edema and an increase in intracranial pressure.

By convention, a stroke has occurred if the clinical deficit persists for longer than 24 hours or if a permanent deficit is seen on neuroimaging that directly correlates with the patient’s syndrome. A transient ischemic attack (TIA), in contrast, involves no permanent tissue damage. Classically, it has been described as a focal deficit that lasts less than 24 hours. However, most patients with a TIA have symptoms for a shorter duration, typically less than 45 minutes. Recognition of TIAs is essential, as they may be a harbinger of stroke. In one study, 10.5% of patients sustained a stroke in the 3 months following the diagnosis of a TIA.1

Anatomy of Cerebral Circulation

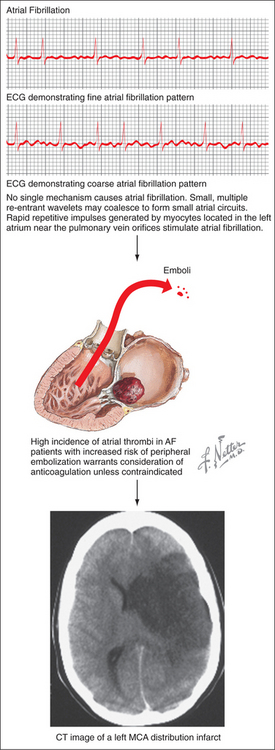

Strokes involve specific vessels of the cerebral circulation and result in focal neurological signs referable to the territory supplied by the affected vessels. Stroke syndromes can broadly be categorized into anterior (carotid) or posterior (vertebro-basilar) circulation phenomena (Figure 79-2). The anterior circulation includes branches of the internal carotid artery and the lenticulostriate arteries, which penetrate deep into the cerebral cortex. These vessels supply much of the cerebral cortex, the subcortical white matter, the basal ganglia, and the internal capsule. Symptoms of anterior circulation strokes depend on the hemisphere involved and the handedness of the patient. Manifestations include aphasia, apraxia, hemi-neglect, hemiparesis, sensory disturbances, and visual field defects. Specific deficits associated with the branches of the anterior circulation are listed in Table 79-1.

Figure 79-2 Circle of Willis showing arterial circulation of the brain.

(Reprinted from Netter Anatomy Illustration Collection, © Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.)

Table 79-1 Anterior and Posterior Circulation Stroke Syndromes

| Circulation | Vessel branch | Syndrome |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior | Anterior cerebral | Contralateral lower extremity paresis, mutism, apathy, pseudobulbar affect |

| Anterior | Middle cerebral | Contralateral hemiparesis, hemi-sensory loss, hemianopsia/quadrantanopsia, aphasia (dominant hemisphere), hemi-inattention (nondominant hemisphere) |

| Posterior | Posterior cerebral | Contralateral homonymous hemianopsia, alexia without agraphia (dominant hemisphere) |

| Posterior | Basilar | Coma, “locked in” syndrome, cranial nerve palsies, hemiparesis/quadriparesis, ataxia |

| Posterior | Vertebral | Lateral medullary (Wallenburg) syndrome, appendicular or truncal ataxia |

Data from Kaufman DM: Clinical neurology for psychiatrists, Philadelphia, 2001, Saunders/Elsevier, p 275.

The posterior circulation consists of a pair of vertebral arteries and a single basilar artery with their branches, including the posterior cerebral arteries (PCAs). These vessels supply the brainstem, the cerebellum, the thalamus, and parts of the occipital and temporal lobes. Symptoms may localize to the brainstem (including coma, vertigo, nausea, cranial nerve palsies, or ataxia). Specific syndromes associated with the branches of the posterior circulation are also listed in Table 79-1.

EPIDEMIOLOGY/RISK FACTORS

Epidemiology

Stroke is the third most common cause of death in the United States, following only heart disease and cancer.2 It is the most common disabling neurological disorder. Each year in the United States, over 700,000 new or recurrent strokes and over 160,000 deaths from stroke occur.3 Furthermore, stroke is a major cause of functional impairment: 15% to 30% of stroke survivors are considered permanently disabled.3

Risk Factors

Several major risk factors for stroke exist. Of these, age is the most important nonmodifiable risk factor; the risk of stroke more than doubles for each decade beyond age 55 years.4 Other nonmodifiable factors include gender (male > female), race (African Americans and Hispanics > European Americans), and genetic contributions.5–10 A number of modifiable stroke risk factors have also been identified. Hypertension is one of the most important, and it is an excellent target for both primary and secondary prevention. Other risk factors include prior stroke or TIA, atrial fibrillation (AF), diabetes mellitus (DM), excessive alcohol use, tobacco use, and hypercholesterolemia.11 In addition, newly identified risk factors for stroke include the metabolic syndrome and obstructive sleep apnea.11

Risk-Profile Generation

Patients at risk for stroke may be stratified according to a variety of risk factors, including advanced age, hypertension, smoking status, DM, hypercholesterolemia, history of cardiovascular disease, and electrocardiographic evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy or AF. One risk-profile model, the Framingham Stroke Profile, uses the Cox proportional-hazards method to generate an individual’s 10-year, gender-specific prediction of stroke risk.12 These and other models are important, as primary prevention efforts often focus on high-risk patients.

ISCHEMIC STROKE

Types

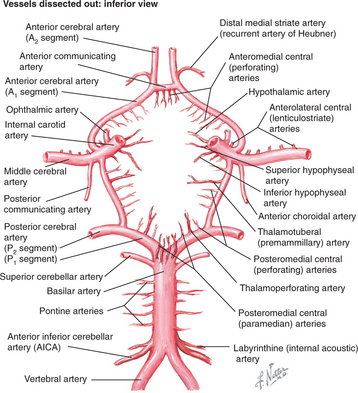

Several pathophysiological mechanisms lead to ischemic stroke: thrombosis, whereby a clot forms within an artery and blocks it; embolism, whereby a clot travels from a remote origin and lodges within an arterial vessel (Figure 79-3); or lipohyalinosis, whereby concentric narrowing of small penetrating arteries results in lacunar infarction. Thrombotic mechanisms cause about 20% of ischemic strokes, embolism causes about 20% of cases, and lacunar infarcts comprise an additional 25%.2 The remainder is caused by more rare conditions or by an undetermined etiology (i.e., “cryptogenic stroke”).

Examination

A careful history is a crucial first step in the management of a suspected acute ischemic stroke. The exact time of onset, to the minute if possible, is an essential data point, as some therapies for the management of acute stroke (such as thrombolysis) are only available within strict time frames. If the exact time of onset is not known, or if the patient was not witnessed at the time of symptom development, the time of onset by default becomes the time at which the patient was last seen to be neurologically normal. A history of similar symptoms, which may suggest a recent TIA or even a recent stroke, should also be ascertained. Essential components of the medical history include a history of cardiac problems, hypertension, DM, hypercholesterolemia, and use of tobacco or drugs. The medication list should be reviewed, especially if the patient is taking anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents. A thorough physical examination should follow, which should include the careful assessment of vital signs (including blood pressure [BP] measured in both arms). The examiner should auscultate the carotid arteries to assess for the presence of carotid bruits. Of note, a lack of a bruit may accompany a complete or an impending occlusion. Most important, a focused neurological assessment should be done with the aim of localizing the lesion supplied by the suspected vessel. Most stroke physicians use a standardized scale (such as the National Institutes of Health [NIH] Stroke Scale), which establishes a method of performing a rapid and focused evaluation and establishes standardized values for comparisons among stroke patients for treatment and research purposes.13

Treatment

Acute Management

In the acute setting, intravenous (IV) thrombolytic therapy with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) may significantly reduce both the short- and long-term sequelae of stroke. Rt-PA exerts its action by converting plasminogen to plasmin, which helps to dissolve fibrin-containing clots. This therapy, approved in 1996 by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) after a landmark 1995 trial by the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), demonstrated a benefit to patients administered rt-PA with acute stroke less than 3 hours old.14 Overall, patients in the rt-PA group were 30% more likely to show minimal or no disability at 3 months, and the mortality rate was not significantly different between treatment and placebo arms.14 The main adverse event was a significantly higher percentage of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage in the treatment arm, and this remains the most important drawback of this treatment.14 Although some trials have indicated a potential benefit for patients who receive rt-PA within 3 to 6 hours, these patients have a higher percentage of symptomatic parenchymal hemorrhages, and thus treatment outside of the 3-hour window is not recommended.15 Some specialized centers may perform intraarterial (IA) thrombolysis as well. However, this is currently of limited availability, and much of the work in this area is considered investigational.16 Another FDA-approved technique for use in acute stroke is the MERCI clot retrieval device, which allows for the mechanical retrieval of an acute thrombus within 8 hours.17 In general, all forms of thrombolytic therapy should be delivered in a dedicated stroke center, where hemodynamic parameters and neurological status may be monitored carefully, and where neurosurgical backup is available in the event that the patient suffers a hemorrhagic event.

Patients who are not considered candidates for thrombolysis should receive multimodal medical management. BP in the acute setting should not be lowered aggressively. Systolic BP in the range of 150 to 160 mm Hg is often tolerated, and it may help to provide additional blood flow to ischemic, but not yet infarcted, tissue (i.e., the “ischemic penumbra”). If a patient has received IV thrombolysis, however, there is a maximum allowable BP of 185/110 mm Hg. Appropriate agents should be used emergently to lower the BP if it exceeds these values. Antiplatelet therapy has also proven beneficial both in the acute setting and for secondary prevention. Anticoagulation, with heparin or Coumadin (or both), may be indicated in conditions that require ongoing anticoagulation (such as AF), but this carries the risk of hemorrhagic conversion of the ischemic infarct. The timing of anticoagulation must take into account the size and location of the stroke, the presence of any hemorrhagic conversion (even if asymptomatic), and the overall risk/benefit profile of the individual patient.

Primary Prevention

Several primary prevention measures have demonstrated efficacy. Control of hypertension is a crucial factor in the reduction of the incidence of stroke.11 A 1997 meta-analysis determined that the use of beta-blockers and diuretics were both effective in the prevention of stroke.18 Tight glucose control in DM is also recommended. Smoking cessation should be strongly encouraged. Unless contraindicated, anticoagulation for chronic conditions (such as AF with a history of thromboembolism) should be continued on a life-long basis. The role of aspirin and other antiplatelet agents in primary prevention has yet to be clarified. A randomized clinical trial of a large cohort of women demonstrated the benefits of aspirin for primary prevention in this population19; however, the benefit across low-risk populations has yet to be demonstrated.20,21 Last, statin therapy has lowered the risk of stroke in patients with known ischemic heart disease,22 but its impact on patients without known cardiac disease remains under study.23

Secondary Prevention

Antiplatelet therapy is a key component of secondary prevention. A 1994 meta-analysis demonstrated that the use of aspirin and other antiplatelet agents (such as clopidogrel) reduced the risk of recurrent nonfatal stroke by 31%.20 Other effective agents include aspirin plus extended-release dipyridamole.24 The use of aspirin in combination with clopidogrel is not recommended, given the lack of additional efficacy and the increased risk of bleeding.25 Control of hypertension is another crucial component of secondary prevention. There may be a particular benefit associated with use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers.26,27 Unless contraindicated, stroke caused by AF should be treated with oral anticoagulation (OAC), with a target international normalized ratio between 2.0 and 3.0.28 Patients should also be strongly encouraged to discontinue smoking. Lipid-lowering therapy has a proven benefit in secondary stroke prevention. A recent clinical trial demonstrated that use of statin therapy reduced the incidence of stroke and other cardiovascular events in patients with prior stroke or TIA.29 In addition, weight loss and increased physical activity should be encouraged in all patients, and moderate alcohol intake allowed.28 Last, carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic carotid stenosis is indicated,30 and it may be considered for patients with severe but asymptomatic disease as well.31 Carotid stenting is another modality that has shown promise in recent years. It is currently being studied in comparison to carotid endarterectomy and in high-risk patients who are considered unsafe for surgery.32

Prognosis

The extent of the deficit and the degree of functional impairment are important prognostic indicators. Negative prognostic factors also include advanced age and the presence of multiple medical co-morbidities. Approximately 80% of stroke patients achieve 1-month survival; however, only about 35% are alive 10 years after a stroke.33

HEMORRHAGIC STROKE

OVERVIEW

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

A subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) refers to bleeding that occurs beneath the arachnoid layer of the meninges. Nontraumatic SAH is most often due to the rupture of a previously undiagnosed saccular aneurysm. This may occur due to a developmental weakness of the vessel wall, and it may be associated with congenital disorders (such as polycystic kidney disease). Other causes of SAH include trauma, rupture of an arteriovenous malformation (AVM), hemorrhagic conversion of an ischemic stroke, primary intracerebral hemorrhage, or rupture of a mycotic aneurysm. SAH is associated with a high mortality rate: up to 45% of patients with this condition die within 30 days of the event.34

Intracerebral Hemorrhage

An intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) refers to a hemorrhage into the brain parenchyma, which may extend into the ventricles or the subarachnoid space. ICH most often occurs in the cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, thalamus, pons, and cerebellum. As in other forms of stroke, lesion location predicts distinct clinical syndromes. Hypertension is the most common etiology, and it is most commonly associated with deeper hemorrhages in the basal ganglia, brainstem, or cerebellum. ICH can also be caused by amyloid angiopathy (especially in elderly patients), coagulopathy, rupture of an AVM, hemorrhagic conversion of an ischemic stroke, recreational drug use, or trauma. These etiologies more commonly cause lobar locations of hemorrhage. ICH also has a notably high mortality rate, with only 38% of patients achieving a 1-year survival.35

Diagnosis

CT scanning is the preferred imaging modality for the detection of both SAH and ICH. Approximately 5% to 10% of SAHs will be undetectable by CT, due to technical limitations. In this case, if SAH is suggested by clinical history, a lumbar puncture should be performed to detect the presence of hemoglobin breakdown products (xanthochromia), which will appear less than 12 hours after the hemorrhage. Further imaging modalities include CTA or cerebral angiography, which may help to identify the aneurysm or other vascular abnormality, and Doppler ultrasound, which can monitor for the later development of cerebral vasospasm, which typically develops 5 to 14 days after the SAH. Routine laboratory testing includes a CBC, metabolic panel, and coagulation parameters. An ECG should also be performed. Typical findings that may accompany SAH include diffuse peaked T waves, a prolonged QT interval, and peaked P waves.36 A neurosurgical consultation is mandatory for further management.

Treatment

For SAH due to aneurysm rupture, current management includes neurosurgical clipping or endovascular coiling of the aneurysm to prevent rebleeding. The optimal approach remains under study. The landmark 2002 International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) study, which randomized 2,143 SAH patients to clipping or to coiling (in cases in which either was deemed feasible), demonstrated improved disability-free survival in the coiling group at 1 year.37 A follow-up study in 2005 of the same population demonstrated continued a survival benefit in the endovascular group for at least 7 years; however, the risk of rebleeding was slightly higher.38 Potential candidates for intervention may be graded according to clinical presentation, severity of hemorrhage, and estimated surgical risk.39 For SAH due to rupture of an AVM, surgical or endovascular correction may be attempted if the anatomy is favorable.

Patients with either SAH or ICH demand urgent attention for airway protection, hemodynamic management in an intensive care setting, and minimization of the sequelae of the initial hemorrhage. For SAH, interventions include bed rest with head of bed elevation to 15 to 20 degrees, careful use of mild sedating agents to control agitation, avoidance of hypotension, prophylactic prevention of vasospasm with calcium channel blockers, and seizure prophylaxis with antiepileptic medications for worse clinical grade patients. Any coagulopathy should be corrected. Hyponatremia due to cerebral salt wasting or the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) is common, and should be investigated and treated accordingly. Fluid restriction is contraindicated in patients with cerebral vasospasm after SAH. Many patients (especially those with hydrocephalus or a depressed level of consciousness) with SAH will require extraventricular drainage (EVD). If cerebral vasospasm develops, medical management typically includes “triple H” therapy, consisting of induced hypertension, hemodilution, and hypervolemia. With refractory vasospasm, direct intraarterial techniques (such as direct infusion of vasodilating medications or angioplasty of severely vasospastic vessels) may be necessary.

With ICH, emergency measures (such as hyperventilation and IV mannitol) to prevent herniation and further brain injury may be required, especially for those patients who may have significant cerebral edema, brainstem compression, or severe mass effect.40,41 Corticosteroids are not efficacious and are not indicated.42 The optimal approach for the management of BP is controversial. Current guidelines include the use of IV antihypertensive agents for patients with a mean arterial BP ≥ 130 mm Hg.41 Regarding neurosurgical intervention, a randomized trial of 1,033 patients with spontaneous ICH did not show overall benefit in the surgical evacuation over the conservative treatment groups.43 However, a neurosurgical approach with low rates of morbidity may still be considered in selected cases. These include cases of cerebellar hemorrhage, which may be more accessible to surgical intervention, and cases of young patients with life-threatening and more superficially located hematomas.41 Future treatments may involve early hemostatic therapy with agents such as recombinant activated factor VII to reduce the volume of hematoma.42

Prognosis

For SAH, survival rates depend in part on the patient’s age and neurological status, the time elapsed since the hemorrhage, co-morbidities, and other factors (such as degree of intracranial pressure). Approximately 50% of survivors have permanent brain injury from a ruptured aneurysm.33 If the SAH is due to an AVM, survival rates are in the range of 90%.33 For ICH, the prognosis depends on the volume of the hematoma, the site of involvement, the presence of coma, the age of the patient, and the presence of intraventricular blood.44–47

NEUROPSYCHIATRIC SEQUELAE OF STROKE

Neuropsychiatric sequelae, including changes in affect, behavior, and cognition, are seen in more than half of post-stroke patients, and may be linked to lesion location (Table 79-2). Although the neuropsychiatric effects of stroke are wide-ranging and variable, symptoms tend to cluster into several categories.

| Cortical Area | Potential Neuropsychiatric Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Frontal Lobes | |

| Orbitofrontal region | Disinhibition, personality change, irritability |

| Dorsolateral region | Executive dysfunction: poor planning, organizing, and sequencing |

| Medial region | Apathy, abulia |

| Left frontal lobe | Nonfluent (Broca’s) aphasia, poststroke depression (possibly) |

| Right frontal lobe | Motor dysprosody |

| Temporal Lobes | |

| Either side | Hallucinations (olfactory, gustatory, tactile, visual, or auditory), episodic fear, or mood changes |

| Left temporal lobe | Short-term memory impairment (verbal, written stimuli), fluent (Wernicke’s) aphasia (left temporoparietal region) |

| Right temporal lobe | Short-term memory impairment (nonverbal stimuli; e.g., music), sensory dysprosody (right temporoparietal region) |

| Left parietal lobe | Gerstmann’s syndrome (finger agnosia, right/left disorientation, acalculia, agraphia) |

| Right parietal lobe | Anosognosia, constructional apraxia, prosopagnosia, hemineglect |

| Occipital lobes | Anton’s syndrome (cortical blindness with unawareness of visual disturbance) |

Post-stroke Depression

Post-stroke depression (PSD) is one of the most common and well-studied phenomena in post-stroke patients. Up to 20% of stroke patients meet the criteria for PSD, and another 20% meet the criteria for minor depression.48–50 Risk factors for the development of PSD include prior major depression, pre-stroke functional impairment, social isolation (including living alone), and possibly female gender.51 An untreated episode of PSD may last for 9 months to 1 year. The etiology of PSD is unclear and may be multifactorial (e.g., related to the degree of disability or cognitive impairment, and perhaps to lesion location as well).52 Depression in this population may be difficult to diagnose for many reasons, including the fact that there is often an overlap of psychiatric and somatic symptoms (such as fatigue). Confounding neurological symptoms (such as expressive aprosodias and aphasia) may hinder a complete evaluation.

PSD has a major impact on functional status, and thus it should be treated actively.53 A full remission from PSD is difficult to achieve.54 However, both selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have proven useful in improving post-stroke mood.55–57 Additionally, low doses of stimulants possess a mild antidepressant quality that may also improve mood. However, as many stroke patients have concurrent cardiac risk factors (such as elevated BP or coronary artery disease [CAD] at baseline), these agents should be used with caution (Table 79-3). For severe depression that has not been alleviated by adequate trials of antidepressants, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been used successfully and safely.58 Nonpharmacological interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, are under investigation but have not proven to be more effective than the use of medication in this population.59

Table 79-3 Indications for Stimulant Use in Post-stroke Depression

Post-stroke Anxiety

Anxiety also commonly affects the post-stroke population. More than 25% of post-stroke patients meet the criteria for a generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), which commonly co-exists with major depression.60,61 SSRIs remain first-line treatment, as they may treat symptoms of both GAD and depression. Benzodiazepines should be used with particular caution, as they may produce disinhibition or signs of toxicity, such as ataxia and oversedation.

Post-stroke Mania

Post-stroke mania occurs much less commonly than PSD. Signs and symptoms are generally similar to those of a primary manic episode and include pressured speech, grandiosity, increase in goal-directed activity, and decreased need for sleep. Symptoms may be correlated with right-sided lesions, particularly in the orbitofrontal cortex and thalamus.62–64 Symptoms may improve with standard treatments for mania, including mood stabilizers (e.g., lithium, valproic acid, and carbamazepine) and atypical antipsychotics. However, there are few randomized clinical trials to demonstrate their benefit.64

Post-stroke Psychosis

Post-stroke psychosis is also uncommon; it is identified in approximately 1% to 2% of all post-stroke patients.65 Temporal lobe insults may predispose to psychosis in this population. Antipsychotics may alleviate some symptoms. However, some psychotic symptoms may arise as a consequence of complex partial seizure activity arising in the temporal lobe, and anticonvulsants, such as carbamazepine, would be the medication of choice in this setting.

Other Syndromes

In addition to the psychiatric syndromes listed previously, other syndromes are seen specifically in post-stroke patients. Catastrophic reactions may affect up to 20% of post-stroke patients.66,67 A mixture of anxiety, aggressive behavior, and compensatory boasting classically characterizes this syndrome. It may be related to lesions involving the anterior subcortical regions and left hemisphere.67,68 Risk factors include a family history of psychiatric illness. Pseudobulbar affect, also referred to as pathological emotional behavior, is a syndrome characterized by the outward emotional expression not correlating to the affect of the situation. SSRIs and TCAs may lead to some improvement in this disorder.69,70 Last, apathy, characterized by a notable lack of feeling or interest, is noted in approximately 20% of post-stroke patients and may co-exist with depression.71,72 It may be related to lesions in the posterior limb of the internal capsule72 and is notoriously difficult to treat.

1 Johnston SC, Gress DR, Browner WS, et al. Short-term prognosis after emergency department diagnosis of TIA. JAMA. 2000;284(22):2901-2906.

2 Albers GW, Amarenco P, Easton JD, et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: the 7th ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126:483-512S.

3 American Heart Association. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2004 update. Dallas: American Heart Association, 2003.

4 Wolfe PA, D’Agostino RB, O’Neal MA, et al. Secular trends in stroke incidence and mortality: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1992;23:1551-1555.

5 Brown RD, Whisnant JP, Sicks JD, et al. Stroke incidence, prevalence, and survival: secular trends in Rochester, Minnesota, through 1989. Stroke. 1996;27:273-380.

6 Sacco RL, Boden-Albala B, Gan R, et al. Stroke incidence among white, black, and hispanic residents in an urban community: the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:259-268.

7 Broderick JP, Brott TG, Kothari R, et al. The Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Stroke Study: preliminary first-ever and total incidence rates of strokes among blacks. Stroke. 1998;29:415-421.

8 Gorelick PB. Cerebrovascular disease in African Americans. Stroke. 1998;29:2656-2664.

9 Howard G, Anderson R, Sorlie P, et al. Ethnic differences in stroke mortality between non-Hispanic whites, Hispanic whites, and blacks: the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Stroke. 1994;25:2120-2125.

10 Rosamond WD, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, et al. Stroke incidence and survival among middle-aged adults: 9-year follow-up of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort. Stroke. 1999;30:736-743.

11 Goldstein LB, Adams R, Alberts MJ, et al. Primary prevention of ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council. Stroke. 2006;37:1583-1633.

12 Wolfe PA, D’Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, et al. Probability of stroke: a risk profile from the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991;22:312-318.

13 Brott T, Adams HP, Olinger CP, et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke. 1989;20:864-870.

14 The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581-1588.

15 Hacke W, Donnan G, Fieschi C, et al. Association of outcomes with early stroke treatment: pooled analysis of ATLANTIS, ECASS, and NINDS rt-PA stroke trials. Lancet. 2004;363(9411):768-778.

16 Furlan A, Higashida R, Wechsler L, et al. Intra-arterial prourokinase for acute ischemic stroke. The PROACT II Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282(21):2003-2011.

17 Gobin YP, Starkman S, Duckwiler GR, et al. MERCI 1: a phase 1 study of mechanical embolus removal in cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2004;35(12):2848-2854.

18 Psaty BM, Smith NL, Siscovick DS, et al. Health outcomes associated with antihypertensive therapies used as first-line agents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 1997;277(9):739-745.

19 Ridker PM, Cook NR, Lee IM. A randomized trial of low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1293-1304.

20 Anti-platelet Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative overview of randomized trials of anti-platelet therapy: 1. Prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged anti-platelet therapy in various categories of patients. BMJ. 1994;308:81-106.

21 Hart RG, Halperin JL, McBride R, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of stroke and other major vascular events: meta-analysis and hypotheses. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:326-332.

22 Pederson TR, Kjekshus J, Pyorala K, et al. Effect of simvastatin on ischemic signs and symptoms in the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:333-335.

23 Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Callahan AS, et al. Design and baseline characteristics of Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) Study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;16(4):389-395.

24 Forbes CD, European Stroke Prevention Study 2. Dipyridamole and acetylsalicylic acid in the secondary prevention of stroke. Int J Clin Pract. 1997;51(4):205-208.

25 Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, et al. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9431):331-337.

26 Chapman N, Huxley R, Anderson MG, et al. Effects of a perindopril-based blood pressure-lowering regimen on the risk of recurrent stroke according to stroke subtype and medical history: the PROGRESS Trial. Stroke. 2004;35:116-121.

27 Ibsen H, Olsen MH, Wachtell K, et al. Does albuminuria predict cardiovascular outcomes on treatment with losartan versus atenolol in patients with diabetes, hypertension, and left ventricular hypertrophy? The LIFE Study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:595-600.

28 Sacco RL, Adams R, Albers G, et al. Guidelines for prevention of stroke in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a statement for healthcare professions from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council on Stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:577-617.

29 Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Callahan A, et al. High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(6):549-559.

30 Barnett HJ, Taylor DW, Eliasziaw M, et al. Benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(20):1415-1425.

31 Chaturvedi S, Bruno A, Feasby T, et al. Carotid endarterectomy—an evidence-based review: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2005;65(6):794-801.

32 Yadav JS, Wholey MH, Kuntz RE, et al. Protected carotid-artery stenting versus endarterectomy in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(15):1493-1501.

33 Aminoff M. Clinical neurology, ed 2. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill, 2005.

34 Broderick JP, Brott TG, Duldner JE, et al. Initial and recurrent bleeding are the major causes of death following subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1994;25(7):1342-1347.

35 Dennis MS, Burn JP, Sandercock PA, et al. Long-term survival after first-ever stroke: the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project. Stroke. 1993;24:796-800.

36 Van der Bergh WM, Algra A, Rinkel GJ. Electrocardiographic abnormalities and serum magnesium in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2004;35(3):644-648.

37 International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) Collaborative Group. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1267-1274.

38 Molyneux AJ, Kerr RS, Yu LM, et al. for the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) Collaborative Group: International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a randomised comparison of effects on survival, dependency, seizures, rebleeding, subgroups, and aneurysm occlusion. Lancet. 2005;366:809-817.

39 Hunt WE, Hess RM. Surgical risk as related to time of interven-tion in the repair of intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1968;28:14-20.

40 Qureshi AI, Geocadin RG, Suarez JI, Ulatowski JA. Long-term outcome after medical reversal of transtentorial herniation in patients with supratentorial mass lesions. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:1556-1564.

41 Qureshi AI, Tuhrim S, Broderick JP, et al. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(19):1450-1460.

42 Mayer SA, Brun NC, Begrup K, et al. Recombinant activated factor VII for acute intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(8):777-785.

43 Mendelow AD, Gregson BA, Fernandes HM, et al. Early surgery versus initial conservative treatment in patients with spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral haematomas in the International Surgical Trial in Intracerebral Hemorrhage (STICH): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9457):387-397.

44 Lisk DR, Pasteur W, Rhoades H, et al. Early presentation of hemispheric intracerebral hemorrhage: prediction of outcome and guidelines for treatment allocation. Neurology. 1994;44:133-139.

45 Tuhrim S, Horowitz DR, Sacher M, et al. Validation and comparison of models predicting survival following intracerebral hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:950-954.

46 Vermeer SE, Algra A, Franke CL, et al. Long-term prognosis after recovery from primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2002;59:205-209.

47 Hemphill JC, Bonovich DC, Besmertis L, et al. The ICH score: a simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2001;32:891-897.

48 Astrom M, Adolfsson R, Asplund K. Major depression in stroke patients: a three year longitudinal study. Stroke. 1993;24:976-982.

49 Eastwood MR, Rifat SL, Nobbs H, et al. Mood disorder following cerebrovascular accident. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:195-200.

50 Robinson RG, Bolduc PL, Price TC. Two-year longitudinal study of poststroke mood disorders: diagnosis and outcome at one and two years. Stroke. 1987;18:837-843.

51 Ouimet MA, Primeau F, Cole MG. Psychosocial risk factors in poststroke depression: a systematic review. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46(9):819-828.

52 Whyte EM, Mulsant BH. Post-stroke depression: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and biological treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:253-264.

53 Robinson RG. Neuropsychiatric consequences of stroke. Annu Rev Med. 1997;48:217-219.

54 Hackett ML, Anderson CS, House AO. Management of depression after stroke: a systematic review of pharmacological therapies. Stroke. 2005;36:1092-1097.

55 Andersen G, Vestergaard K, Lauritzen L. Effective treatment of poststroke depression with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram. Stroke. 1994;25:1099-1104.

56 Wiart L, Petit H, Joseph PA, et al. Fluoxetine in early poststroke depression: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Stroke. 2000:1829-1832.

57 Lipsey JR, Robinson RG, Pearlson GD, et al. Nortriptyline treatment of poststroke depression: a double-blind study. Lancet. 1984;1:297-300.

58 Currier MB, Murray GB, Welch CC. Electroconvulsive therapy for poststroke depressed geriatric patients. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1992;4(2):140-144.

59 Lincoln NB, Flannaghan T. Cognitive behavioral therapy for depression following stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Stroke. 2003;34:111-115.

60 Castillo CS, Schultz SK, Robinson RG. Clinical correlates of early-onset and late-onset poststroke generalized anxiety. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1174-1179.

61 Astrom M. Generalized anxiety disorder in stroke patients: a three-year longitudinal study. Stroke. 1996;27:270-275.

62 Robinson RG, Boston JD, Starkstein SE, et al. Comparison of cortical and subcortical lesions in the production of post-stroke depression matched for size and location of lesions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:247-252.

63 Cummings JL, Mendez MF. Secondary mania with focal cerebrovascular lesion. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;141:172-178.

64 Starkstein SE, Mayberg HS, Berthier ML, et al. Secondary mania: neuroradiological and metabolic findings. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:652-659.

65 Rabins PV, Starkstein SE, Robinson RG. Risk factors for developing atypical (schizophreniform) psychosis following stroke. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1991;3:6-9.

66 Starkstein SE, Fedoroff JP, Price TR, et al. Catastrophic reaction after cerebrovascular lesions: frequency, correlates, and validation of a scale. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;5:189-194.

67 Carota A, Rossetti AO, Karapanayiotides T, et al. Catastrophic reaction in acute stroke: a reflex behavior in aphasic patients. Neurology. 2001;57:1902-1905.

68 Morrison JH, Molliver ME, Grzanna R. Noradrenergic innervation of the cerbral cortex: widespread effects of local cortical lesions. Science. 1979;205:313-316.

69 Robinson RG, Parikh RM, Lipsey JR, et al. Pathological laughing and crying following stroke: validation of measurement scale and double-blind treatment study. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:286-293.

70 Andersen G, Vestergaard K, Riis J. Citalopram for poststroke pathological crying. Lancet. 1993;342:837-839.

71 Starkstein SE, Fedoroff JP, Price TR, et al. Apathy following cerebrovascular lesions. Stroke. 1993;24(11):1625-1630.

72 Yudofsky SC, Shales RE. Essentials of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004.

Gilman S, Newman SN. Manter and Gatz’s essentials of clinical neuroanatomy and neurophysiology, ed 10. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 2003.

Goetz C. Textbook of clinical neurology, ed 2. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2000.

Huffman JC, Smith FA, Stern TA. Patients with neurological conditions. I. Seizures (including nonepileptic seizures), cerebrovascular disease, and traumatic brain injury). In: Stern TA, Fricchione GL, Cassem NH, et al, editors. Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of general hospital psychiatry. ed 5. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2004:457-477.

Kaufman D. Clinical neurology for psychiatrists, ed 5. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2001.

Mayer SA, Rincon F. Treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:662-672.

Schiffer RB, Rao SM, Fogel BS. Neuropsychiatry, ed 2. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.

Weiner W, Goetz C, editors. Neurology for the non-neurologist, ed 5, New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004.