CHAPTER 78 Pain

OVERVIEW

Pain, as determined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), is “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage.”1 This chapter will describe the physiological aspects of pain transmission, pain terminology, and pain assessment; discuss the major classes of medications used to relieve pain; and outline the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric conditions that often affect patients with chronic pain.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Psychiatric co-morbidity (e.g., anxiety, depression, personality disorders, and substance use disorders [SUDs]) afflicts those with both non–cancer-related and cancer-related pain. Epidemiological studies indicate that roughly 30% of those in the general population with chronic musculoskeletal pain also have depression or an anxiety disorder.2 Similar rates exist in those with cancer pain. In clinic populations, 50% to 80% of pain patients have co-morbid psychopathology, including problematic personality traits. The personality (i.e., the characterological or temperamental) component of negative affect has been termed neuroticism, which may be best described as “a general personality maladjustment in which patients experience anger, disgust, sadness, anxiety, and a variety of other negative emotions.”3 Frequently, in pain clinics, maladaptive expressions of depression, anxiety, and anger are grouped together as disorders of negative affect, which have an adverse impact on the response to pain.4

Rates of substance dependence in chronic pain patients are also elevated relative to the general population, and several studies have found that 15% to 26% of chronic pain patients have a co-morbid substance (e.g., illegal drugs or prescription medications) dependence disorder.5 Prescription opiate addiction is a growing problem that affects approximately 5% of those who have been prescribed opiates for chronic pain (although good epidemiology studies are lacking). Other chapters in this textbook focus more specifically on SUDs. This chapter will concentrate on those with affective disorders and somatoform disorders in the setting of chronic pain.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF PAIN TRANSMISSION

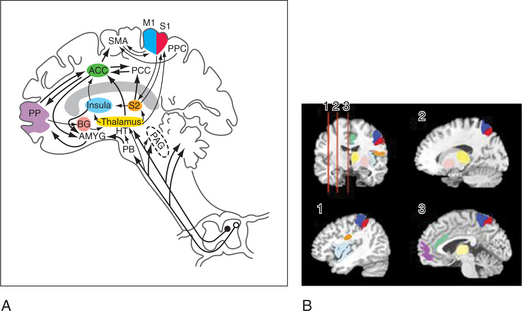

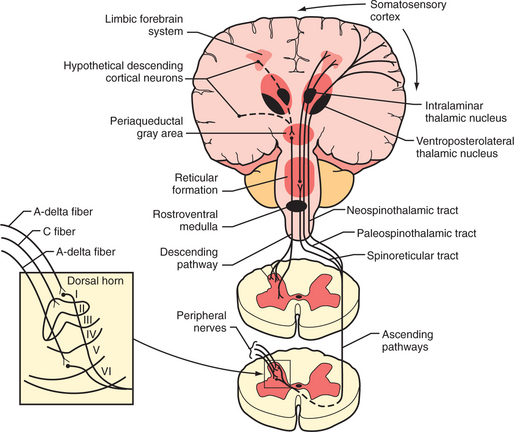

Tissue injury stimulates the nociceptors by the liberation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), protons, kinins, and arachidonic acid from the injured cells; histamine, serotonin, prostaglandins, and bradykinin from the mast cells; and cytokines and nerve growth factor from the macrophages. These substances and decreased pH cause a decrease in the threshold for activation of the nociceptors, a process called peripheral sensitization. Subsequently, axons transmit the pain signal to the spinal cord, and to cell bodies in the dorsal root ganglia (Figure 78-1). Three different types of axons are involved in the transmission of pain from the skin to the dorsal horn. A-β fibers are the largest and most heavily myelinated fibers that transmit awareness of light touch. A-Δ fibers and C fibers are the primary nociceptive afferents. A-Δ fibers are 2 to 5 mcm in diameter and are thinly myelinated. They conduct “first pain,” which is immediate, rapid, and sharp, with a velocity of 20 m/sec. C fibers are 0.2 to 1.5 mcm in diameter and are unmyelinated. They conduct “second pain,” which is prolonged, burning, and unpleasant, at a speed of 0.5 m/sec.

Figure 78-1 Schematic diagram of neurological pathways for pain perception.

(From Hyman SH, Cassem NH: Pain. In Rubenstein E, Fedeman DD, editors: Scientific American medicine: current topics in medicine, subsection II, New York, 1989, Scientific American. Originally from Stern TA, Herman JB, editors: Psychiatry update and board preparation, 2004, McGraw-Hill.)

A-Δ and C fibers enter the dorsal root and ascend or descend one to three segments before synapsing with neurons in the lateral spinothalamic tract (in the substantia gelatinosa in the gray matter) (see Figure 78-1). Second pain transmitted with C-fibers is integrally related to chronic pain states. Repetitive C-fiber stimulation can result in a progressive increase of electrical discharges from second-order neurons in the spinal cord. NMDA receptors play a role when prolonged activation occurs. This pain amplification is related to a temporal summation of second pain or “wind-up.” This hyperexcitability of neurons in the dorsal horn contributes to central sensitization, which can occur as an immediate or as a delayed phenomenon. In addition to wind-up, central sensitization involves several factors: activation of A-beta fibers and lowered firing thresholds for spinal cord cells that modulate pain (i.e., they trigger pain more easily); neuroplasticity (a result of functional changes, including recruitment of a wide range of cells in the spinal cord so that touch or movement causes pain); convergence of cutaneous, vascular, muscle, and joint inputs (where one tissue refers pain to another); or aberrant connections (electrical short-circuits between the sympathetic and sensory nerves that produce causalgia). Inhibition of nociception in the dorsal horn is functionally quite important. Stimulation of the A-Δ fibers not only excites some neurons, but it also inhibits others. This inhibition of nociception through A-Δ fiber stimulation may explain the effects of acupuncture and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS).

The lateral spinothalamic tract crosses the midline and ascends toward the thalamus. At the level of the brainstem more than half of this tract synapses in the reticular activating system (in an area called the spinoreticular tract), in the limbic system, and in other brainstem regions (including centers of the autonomic nervous system). Another site of projections at this level is the periaqueductal gray (PAG) (Figure 78-2), which plays an important role in the brain’s system of endogenous analgesia. After synapsing in the thalamic nuclei, pain fibers project to the somatosensory cortex, located posterior to the Sylvian fissure in the parietal lobe, in Brodmann’s areas 1, 2, and 3. Endogenous analgesic systems involve endogenous peptides with opioid-like activity in the central nervous system (CNS) (e.g., endorphins, enkephalins, and dynorphins). Different opioid receptors (mu, kappa, and delta receptors) are involved in different effects of opiates. The centers involved in endogenous analgesia include the PAG, the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), the amygdala, the parabrachial plexus (in the pons), and the rostral ventromedial medulla.

The descending analgesic pain pathway starts in the PAG (which is rich in endogenous opiates), projects to the rostral ventral medulla, and from there descends through the dorsolateral funiculus of the spinal cord to the dorsal horn. The neurons in the rostral ventral medulla use serotonin to activate endogenous analgesics (enkephalins) in the dorsal horn. This effect inhibits nociception at the level of the dorsal horn since neurons that contain enkephalins synapse with spinothalamic neurons. Additionally, there are noradrenergic neurons that project from the locus coeruleus (the main noradrenergic center in the CNS) to the dorsal horn and inhibit the response of dorsal horn neurons to nociceptive stimuli. The analgesic effect of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) is thought to be related to an increase in serotonin and norepinephrine that inhibits nociception at the level of the dorsal horn, through their effects on enhancing descending pain inhibition from above.

CORTICAL SUBSTRATES FOR PAIN AND AFFECT

Advances in neuroimaging have linked the function of multiple areas in the brain with pain and affect. These areas (e.g., the ACC, the insula, and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex [DLPFC]) form functional units through which psychiatric co-morbidity may amplify pain and disability (see Figure 78-2). These areas are part of the spinolimbic (also known as the medial) pain pathway,6 which runs parallel to the spinothalamic tract and receives direct input from the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. The interactions among the function of these areas, pain perception, and psychiatric illness are still being investigated. The spinolimbic pathway is involved in descending pain inhibition (which includes cortical and subcortical structures), whose function may be negatively affected by the presence of psychopathology. This, in turn, could lead to heightened pain perception. Coghill and colleagues7 have shown that differences in pain sensitivity between patients can be correlated with differences in activation patterns in the ACC, the insula, and the DLPFC. The anticipation of pain is also modulated by these areas, suggesting a mechanism by which anxiety about pain can amplify pain perception. The disruption or alteration of descending pain inhibition is a mechanism of neuropathic pain, which can be described as central sensitization that occurs at the level of the brain, a concept supported by recent neuroimaging studies of pain processing in the brains of patients with fibromyalgia.8 The ACC, the insula, and the DLPFC are also laden with opioid receptors, which are less responsive to endogenous opioids in pain-free subjects with high negative affect.9 Thus, negative affect may diminish the effectiveness of endogenous and exogenous opioids through direct effects on supraspinal opioid binding.

INTERACTIONS BETWEEN PAIN AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

The majority of patients with chronic pain and a psychiatric condition have an organic or physical basis for their pain. However, the perception of pain is amplified by co-morbid psychiatric disorders, which predispose patients to develop a chronic pain syndrome. This is commonly referred to as the diathesis-stress model, in which the combination of physical, social, and psychological stresses associated with a pain syndrome induces significant psychiatric co-morbidity.4 This can occur in patients with or without a pre-existing vulnerability to psychiatric illness (e.g., a genetic or temperamental risk factor). Regardless of the order of onset of psychopathology, patients with chronic pain and psychopathology report greater pain intensity, more pain-related disability, and a larger affective component to their pain than those without psychopathology. As a whole, studies indicate that it is not the specific qualities or symptomatology of depression, anxiety, or neuroticism, but the overall levels of psychiatric symptoms that are predictive of poor outcome.10 Depression, anxiety, and neuroticism are the psychiatric conditions that most often co-occur in patients with chronic pain, and those with a combination of pathologies are predisposed to the worst outcomes.

PAIN TERMINOLOGY

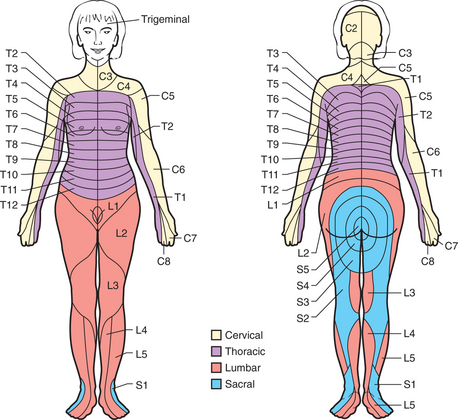

Chronic pain (i.e., pain that persists beyond the normal time of healing or lasts longer than 6 months) involves different mechanisms in local, spinal, and supraspinal levels. Characteristic features include vague descriptions of pain and an inability to describe the pain’s timing and localization. It is usually helpful to determine the presence of a dermatomal pattern (Figure 78-3), to determine the presence of neuropathic pain, and to assess pain behavior.

Figure 78-3 Schematic diagram of segmental neuronal innervation by dermatomes.

(From Hyman SH, Cassem NH: Pain. In Rubenstein E, Fedeman DD, editors: Scientific American medicine: current topics in medicine, subsection II, New York, 1989, Scientific American. Originally from Stern TA, Herman JB, editors: Psychiatry update and board preparation, 2004, McGraw-Hill.)

Myofascial pain can arise from one or several of the following problems: hypertonic muscles, myofascial trigger points, arthralgias, and fatigue with muscle weakness. Myofascial pain is generally used to describe pain from muscles and connective tissue. Myofascial pain results from a primary diagnosis (e.g., fibromyalgia) or, as more often is the case, a co-morbid diagnosis (e.g., with vascular headache or with a psychiatric diagnosis).

ASSESSMENT OF PAIN

The evaluation of pain focuses first on five questions: (1) Is the pain intractable because of nociceptive stimuli (e.g., from the skin, bones, muscles, or blood vessels)? (2) Is the pain maintained by non-nociceptive mechanisms (i.e., have the spinal cord, brainstem, limbic system, and cortex been recruited as reverberating pain circuits)? (3) Is the complaint of pain primary (as occurs in disorders such as major depression or delusional disorder)? (4) Is there a more efficacious pharmacological treatment? (5) Have pain behavior and disability become more important than the pain itself? Answering these questions allows the mechanism(s) of the pain and suffering to be pursued. A psychiatrist’s physical examination of the pain patient typically includes examination of the painful area, muscles, and response to pinprick and light touch (Table 78-1).

Table 78-1 General Physical Examination of Pain by the Psychiatrist

| Physical Finding | Purpose of Examination |

|---|---|

| Motor deficits |

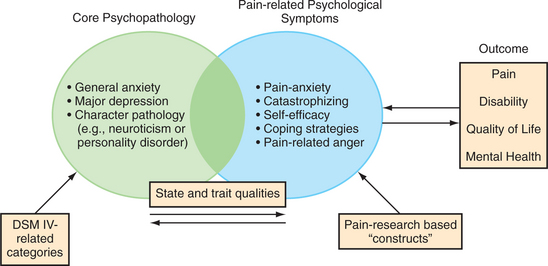

CORE PSYCHOPATHOLOGY AND PAIN-RELATED PSYCHOLOGICAL SYMPTOMS

In patients with chronic pain, heightened emotional distress, negative affect, and elevated pain-related psychological symptoms (i.e., those that are a direct result of chronic pain, and when the pain is eliminated, the symptoms disappear) can all be considered as forms of psychopathology and psychiatric co-morbidity, since they represent impairments in mental health and involve maladaptive psychological responses to medical illness (Figure 78-4). This approach melds methods of classification from psychiatry and behavioral medicine to describe the scope of psychiatric disturbances in patients with chronic pain. In pain patients the most common manifestations of psychiatric co-morbidity involve one or more core psychopathologies in combination with pain-related psychological symptoms. Unfortunately, not all patients and their symptoms fit neatly into DSM categories of illness.

Pain-related anxiety (which includes state and trait anxiety related to pain) is the form of anxiety most germane to pain.11 Elevated levels of pain-related anxiety (such as fear of pain) also meet DSM-IV criteria for an anxiety disorder due to a general medical condition. Since anxiety straddles both domains of core psychopathology and pain-related psychological symptoms, the assessment of anxiety in a patient with chronic pain (as detailed below) must include a review of manifestations of generalized anxiety as well as pain-specific anxiety symptoms (e.g., physiological changes associated with the anticipation of pain).

Poor coping skills (often involving passive responses to chronic pain [e.g., remaining bed-bound] and mistakenly assuming that chronic pan is indicative of ongoing tissue damage), catastrophization (with cognitive distortions that are centered around pain), and low self-efficacy (i.e., with a low estimate by the patient of what he or she is capable of doing) are linked with pain-related psychological symptoms and behaviors.12 Poor copers employ few self-management strategies (such as using ice, heat, or relaxation strategies). A tendency to catastrophize often predicts poor outcome and disability, independent of other psychopathology, such as major depression. The duration of chronic pain and psychiatric co-morbidity are each independent predictors of pain intensity and disability. High levels of anger (which occur more often in men) can also explain a significant variance in pain severity.13

PAIN AND CO-MORBID PSYCHIATRIC CONDITIONS

Virtually all psychiatric conditions are treatable in patients with chronic pain, and the majority of patients who are provided with appropriate treatment improve significantly. Many physicians who treat pain patients often do not realize that this is the case. Of the disorders that most frequently afflict patients with chronic pain, major depression and anxiety disorders are the most common; moreover, they have the best response to medications. Whenever possible, medications that are effective for psychiatric illness and that have independent analgesic properties should be used. Independent analgesia refers to the efficacy of a pain medication (such as a TCA for neuropathic pain), which is independent of its effect on mood.14

Major Depression

Symptoms

Major depressive disorder (MDD) can be diagnosed by DSM-IV or similar research criteria in approximately 15% of those who suffer from chronic pain and in 50% of patients in chronic pain clinics. Recurrent affective illness, a family history of depression, and other psychiatric conditions (e.g., anxiety or substance use disorders) are often present. MDD can be distinguished from situational depression (also termed demoralization or an adjustment disorder with depressed mood) by the triad of persistently low mood, neurovegetative symptoms, and changes in self-attitude that last at least 2 weeks.15 It may be important to distinguish which neurovegetative signs (such as sleep abnormalities) are the result of pain and which are the result of depression. However, given the high rate of co-morbid depression in chronic pain patients, it is prudent to err on the side of attributing neurovegetative symptoms to depression, particularly if they are accompanied by changes in mood or self-attitude. MDD is a serious com plication of persistent pain; if not treated effectively it will reduce the effectiveness of all pain treatments. Even low levels of depression (“subthreshold depression”) may worsen the physical impairment associated with chronic pain, and it should be treated.

Medication Treatment

There is some evidence that pain patients with MDD are more treatment-resistant, particularly when their pain is not effectively managed.16 In general, the first-line agent for a patient in pain is an agent with independent analgesic properties. Among the antidepressants these include the TCAs and SNRIs (duloxetine and venlafaxine). Each has shown efficacy in a variety of neuropathic pain conditions. The details of prescribing a specific antidepressant are covered elsewhere in this text.

Anxiety Disorders

Symptoms

Anxiety disorders encompass a broad spectrum of disorders (including generalized anxiety disorder [GAD], panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder [OCD], and posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]). In addition, pain-related anxiety is the primary manner in which anxiety disorders are manifest in those with chronic pain.11 Anxiety is prevalent in chronic pain clinics, with 30% to 60% of the patients experiencing pathological anxiety.17 Among the anxiety disorders, GAD is the condition that most often afflicts pain patients. More than 50% of patients with anxiety disorders also have a current or past history of MDD or another psychiatric disorder. Alcohol and substance abuse commonly accompany chronic pain; consequently, recognition and treatment of co-morbid depression and substance abuse are critical to long-term treatment outcome.

In pain patients, situational (state) anxiety may be centered on the pain itself and its negative consequences (pain-anxiety). Patients may have conditioned fear, believing that activities will cause uncontrollable pain, causing avoidance of those activities. Pain may also activate thoughts that a person is seriously ill.11 Questions such as the following can be helpful: “Does the pain make you panic? If you think about your pain, do you feel your heart beating fast? Do you have an overwhelming feeling of dread or doom? Do you experience a sense of sudden anxiety that overwhelms you?”

Treatment

Overall, CBT demonstrates the best treatment outcomes for anxiety disorders, including pain-specific anxiety in chronic pain patients. Further improvement can be obtained with relaxation therapy, meditation, and biofeedback. Physical therapy by itself, with no other psychological treatment, is an effective therapy for addressing the fear of pain (termed kinesiophobia, the fear of movement because of pain). A flexibility program addresses muscle disuse (which by itself creates pain) and imparts several psychological insights: activity and function can be improved, despite high levels of pain; it is more meaningful to be active with pain than to remain inactive with pain; and fear of pain and reinjury can be dimin ished. Antidepressants are effective, but many need to be used at higher doses than are typically prescribed for depression. Anxiolytics (such as benzodiazepines and buspirone) are most useful in the initial stages of treatment. However, the side effects and potential for physiological dependency make them a poor choice for long-term treatment.

Antidepressants

Antidepressants may take 2 to 4 weeks until improvement is noted. To improve compliance, escalation of doses must be slow, because anxious patients tolerate side effects poorly. Antidepressants reduce the overall level of anxiety and prevent anxiety or panic attacks, but they have no role in the treatment of acute anxiety. Among antidepressants the SSRIs are most effective. Effective doses are often higher than those used for depression. Of the SNRIs, both venlafaxine and duloxetine have demonstrated efficacy in GAD.18,19

Somatoform Disorders

Classification

The somatoform disorders comprise a group of disorders in which complaints and anxiety about physical symptoms are the dominant features. These complaints exist in the absence of sufficient organic findings to explain the extent of a person’s pain. Most often there is a physical basis (including functional pathology, such as neuropathic pain) for at least a portion of the pain complaints, in which symptom-reporting is magnified by somatizing. Somatization is best thought of as a process. The spectrum of somatization includes amplification of symptoms, which entails “focusing upon the symptoms, racking with intense alarm and worry, extreme disability, and a reluctance to relinquish them.”20 Pain-related psychological symptoms amplify pain perception and disability. Hence, there is a tremendous overlap between the somatoform component of a chronic pain syndrome and other psychiatric co-morbidities. Four somatoform disorders may involve pain: somatization disorder, conversion disorder, hypochondriasis, and pain disorder (with or without a physical basis for pain). Somatoform disorders without any physical basis for pain are estimated to occur in 5% to 15% of patients with chronic pain who receive pain treatment.21

Symptom Presentation

Among somatizers, pains in the head or neck, epigastrium, and limbs predominate. Visceral pains from the esophagus, abdomen, and pelvis are associated with a high rate of psychiatric co-morbidity, particularly somatoform disorders, which can be challenging to diagnose.22 Missed ovarian cancers, neuropathic pain following inflammatory disorders, and referred pain are often overlooked because of the nonspecific presentations of visceral pain. Sufferers from somatoform disorders often have painful physical complaints and excessive anxiety about their physical illness. The most common co-morbid conditions among somatoform-disordered pain patients are MDD and anxiety disorders. Patients with somatization disorder consume health care resources at nine times the rate of the average person in the United States.

GENERAL PRINCIPALS OF MULTIMODAL ANALGESIA

Major Medication Classes

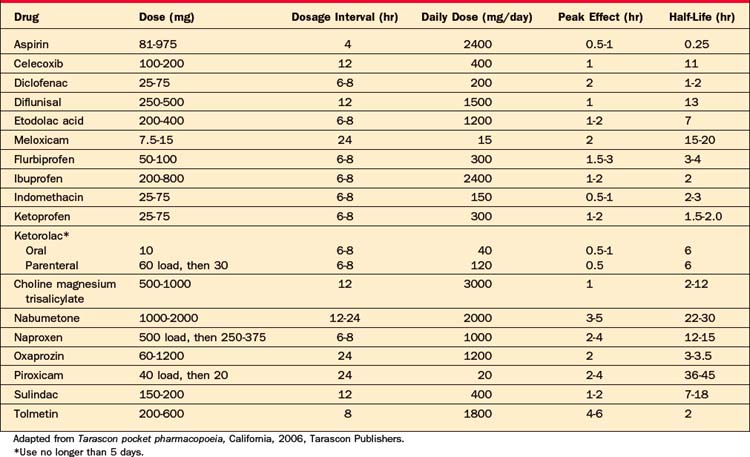

Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are useful for acute and chronic pain (such as pain due to inflammation, muscle pain, vascular pain, or posttraumatic pain). NSAIDs are generally equally efficacious (whether they are nonselective or COX-2 inhibitors) and they have similar side effects, but there is great individual variability in response across the different NSAIDs (Table 78-2). Ketorolac (up to 30 mg every 6 hours) intramuscularly (IM) or intravenously (IV) followed by oral dosing has a rapid onset and a high potency, enabling it to be substituted for morphine (30 mg of ketorolac is equivalent to 10 mg of morphine). It should be used for no more than 5 days.

Tricyclic Antidepressants

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are one of the primary medications used to treat neuropathic pain syndromes; TCAs have both independent analgesic properties and effects as adjuvant agents. A series of studies by Max and others14 have illustrated the analgesic properties of TCAs, which are independent of their effects on improving depression. TCAs have been shown to be effective for the pain associated with diabetic neuropathy, for chronic regional pain syndromes, for chronic headache, for post-stroke pain, and for radicular pain. While the early studies were done with amitriptyline and desipramine, subsequent studies have confirmed that other TCAs also have equivalent analgesic properties. Of note, the typical doses for the analgesic benefit of TCAs (25 to 75 mg) are lower than the doses generally used for antidepressant effect (150 to 300 mg). Nevertheless, there is a dose-response relationship for analgesia, and some patients benefit from a TCA used in the traditional antidepressant dose range, in conjunction with blood level monitoring. A TCA and an anticonvulsant are often combined for the treatment of chronic pain, and this combination facilitates treatment of mood disorders. Since pain patients are frequently on a variety of medications that may potentially increase TCA serum levels, the value of blood level monitoring, even at low doses, cannot be understated.

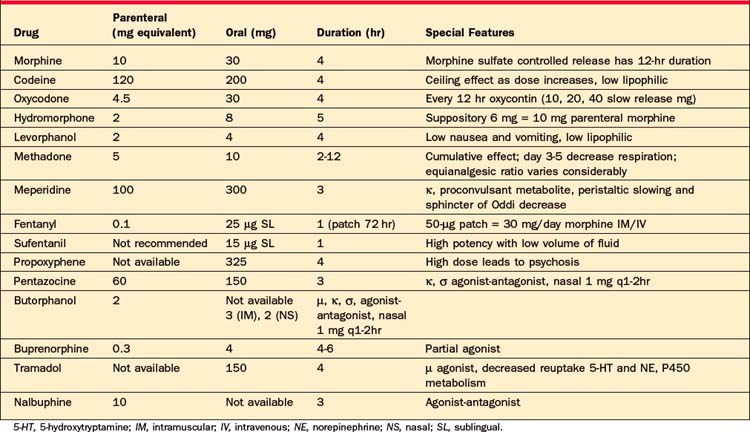

Opioids

Acute, severe, and unremitting pains in cancer patients, as well as non–cancer-related chronic pain, which have been refractory to other medication modalities typically requires treatment with opioids. At times, opioids are the most effective treatment for chronic, nonmalignant pain, such as the pain associated with postherpetic neuralgia, degenerative disorders, and vascular conditions. Nociceptive pain and absence of any co-morbid drug abuse have been associated with long-term opioid treatment efficacy. Morphine is often the initial opioid of choice for acute and chronic pain because it is well known to most physicians and has a good safety profile. Beyond these starting points, the basic principles of opioid treatment are outlined in Tables 78-3 and 78-4.

Tramadol deserves special mention because it does have weak mu-opioid receptor activity, but it is not classified as a controlled substance in the United States. It also has SNRI properties. Its analgesic mechanism is unknown, but it is thought to enhance descending pain inhibition. Tramadol should not be prescribed concurrently with SSRIs because of a unique interaction that results in a dramatic reduction in seizure threshold. Caution should be taken when prescribing it with other medications (such as bupropion, TCAs, and neuroleptics) that also lower the seizure threshold.

1 IASP Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain terms: a list with definitions and notes on usage. Pain. 1979;6(3):249-252.

2 Von Korff M, Crane P, Lane M, et al. Chronic spinal pain and physical-mental comorbidity in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Pain. 2005;113(3):331-339.

3 Walker EA, Keegan D, Gardner G, et al. Psychosocial factors in fibromyalgia compared with rheumatoid arthritis: II. Sexual, physical, and emotional abuse and neglect. Psychosom Med. 1997;59(6):572-577.

4 Fernandez E. Interactions between pain and affect. In Anxiety, depression, and anger in pain. Dallas: Advanced Psychological Resources; 2002.

5 Strain EC. Assessment and treatment of comorbid psychiatric disorders in opioid-dependent patients. Clin J Pain. 2002;18(4 suppl):S14-S27.

6 Sprenger T, Valet M, Boecker H, et al. Opioidergic activation in the medial pain system after heat pain. Pain. 2006;122:63-67.

7 Coghill RC, McHaffie JG, Yen YF. Neural correlates of interindividual differences in the subjective experience of pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100(14):8538-8542.

8 Gracely RH, Petzke F, Wolf JM, Clauw DJ. Functional magnetic resonance imaging evidence of augmented pain processing in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(5):1333-1343.

9 Zubieta JK, Ketter TA, Bueller JA, et al. Regulation of human affective responses by anterior cingulate and limbic mu-opioid neurotransmission. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(11):1145-1153.

10 Nelson D, Novy D. Self-report differentiation of anxiety and depression in chronic pain. J Pers Assess. 1997;69(2):392-407.

11 McCracken L, Gross RT, Aikens J, Carnrike CLJr. The assessment of anxiety and fear in persons with chronic pain: a comparison of instruments. Behav Res Ther. 1996;34(11):927-933.

12 Keefe FJ, Rumble ME, Scipio CD, et al. Psychological aspects of persistent pain: current state of the science. J Pain. 2004;5(4):195-211.

13 Turk DC, Monarch ES. Biopsychosocial perspective on chronic pain. In: Turk DC, Gatchel R, editors. Psychological approaches to pain management. New York: Guilford Press, 2002.

14 Max MB, Lynch SA, Muir J. Effects of desipramine, amitriptyline and fluoxetine on pain in diabetic neuropathy. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1250-1256.

15 McHugh P, Slavney P. The perspectives of psychiatry. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

16 Gallagher RM, Verma S. Managing pain and co-morbid depression: a public health challenge. Semin Clin Neuropsych. 1999;4(3):203-220.

17 Koenig T, Clark MR. Advances in comprehensive pain management. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1996;19(3):589-611.

18 Thase ME, Entsuah AR, Rudolph RL. Remission rates during treatment with venlafaxine or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178(3):234-241.

19 Goldstein DJ, Lu Y, Detke MJ, et al. Duloxetine vs. placebo in patients with painful diabetic neuropathy. Pain. 2005;116:109-118.

20 Barsky AJ. Patients who amplify bodily sensations. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91(1):63-70.

21 Sigvardsson S, von Knorring A, Bohman M. An adoption study of somatoform disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41(9):853-859.

22 McDonald J. What are the causes of chronic gynecological pain disorders? APS Bulletin. 1995;5(6):20-23.