CHAPTER 77 Headache

OVERVIEW

Headache is one of the most common medical complaints; up to 90% of the general population has experienced tension-type headache, for example.1 Among pain conditions, recurrent headache disorders account for the bulk of lost work time and disability.2 Many headaches are self-treated, but headache is still a leading cause of emergency department (ED) and physician visits. Most people with recurrent troublesome headaches have tension-type, migraine, or cluster headaches. These are referred to as “primary headaches” in the widely used International Classification of Headache Disorders—II (Table 77-1).3 It is vitally important, however, that clinicians rule out life-threatening causes of headaches.

Table 77-1 International Headache Society Classification of Headache Disorders—II

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

The lifetime prevalence of the most common of headaches, the tension-type headache, is estimated at 30% to 80%,4 though most everyone has had this type of headache at one time or another.

Over 28 million Americans have migraines; half remain undiagnosed.5 Approximately 20% of women suffer from migraines, as opposed to 6% of men.6 Worldwide prevalence studies roughly mirror the United States data. Prevalence peaks during the average individual’s most productive years, from ages 25 to 55. The World Health Organization con-siders severe migraine to be among the four most disabling human conditions along with acute psychosis, dementia, and quadriplegia.

Chronic daily headache, a collective term that refers to primary headaches that occur more than 14 (or more than 15 as in the International Headache Society [IHS] classification) days per month for at least 3 months, shows a stable worldwide prevalence of about 4%,7 though there may be significant variation in the individuals who make up this group. Frequently, chronic daily headache may develop from preexisting migraines or tension-type headaches. Less commonly, the pattern may develop de novo (Table 77-2).8 Risk factors for chronic daily headache include female sex, low education level, medication overuse, a history of head or neck trauma, and cigarette smoking.7

Table 77-2 Conditions Associated with Chronic Daily Headaches

GENETICS

Multiple studies indicate a genetic influence in many of the primary headaches. The inheritance in migraine is likely multifactorial, and the odds ratio may increase proportionate to the severity of migraine in the proband but does not seem to relate to the type of headache. Anticipation is noted over generations, with a tendency toward earlier age of onset. Notwithstanding, less than 50% of migraine cases are thought to exhibit genetic influences,9 thus this is likely also a common sporadic condition.

In patients with a rare form of migraine, familial hemiplegic migraine, the responsible genetic defect results in calcium channel dysfunction (channelopathy) that is thought to explain the migraine symptoms in these patients. Familial hemiplegic migraine has been associated with two mutations. CACNA1A gene on chromosome 19 is affected in FHM1 and ATP1A2 on chromosome 1 is affected in FHM2.10 Though the first “migraine gene” has been uncovered and thus is a model for studying the genetic basis of migraine, translation of this information to the more common forms of migraine is still in process.

In tension-type headache, the high prevalence confounds the detection of a genetic influence. Nonetheless, studies of several large populations do suggest a complex multifactorial mode of inheritance in favor of a sporadic condition. A genetic influence is likely in cluster headache as well, though the exact mode is unclear, possibly an autosomal dominant mode with reduced penetrance or an autosomal recessive pattern.11

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

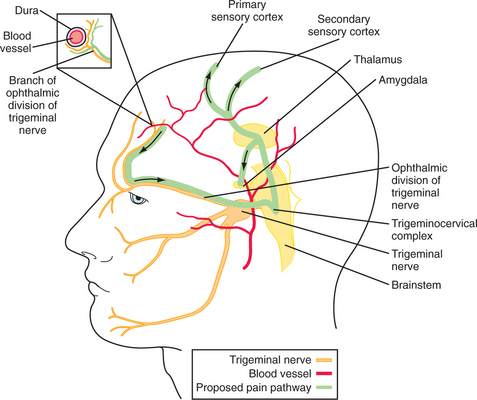

Except for the posterior fossa, which is supplied by the high cervical nerve roots, most head pain is mediated through the first division of the trigeminal nerve.12 Nociceptive C and A-delta fibers innervate the skin, periosteum, large vessels (arteries, veins, and sinuses) and meninges13 (Figure 77-1). Thus, pain may arise from any of these areas, yet not from the substance of the brain, which contains no nociceptive fibers. The cervical and trigeminal nociceptive information is distributed to the “trigeminocervical complex,” a large ipsilateral nuclear group spanning the trigeminal nucleus caudalis (rostrally) to the high cervical dorsal horn cells (caudally). Second-order pathways then cross from there and terminate in the thalamus; third-order pathways then bring the information to the cortex. Descending endogenous inhibitory pain systems may influence the incoming signals at the juncture between the first- and second-order neurons. This simplified scheme may mediate most, if not all, head pain no matter what the cause.

As to the cause of migraine specifically, dysfunction in these brainstem systems, possibly genetically determined, is one theory of migraine generation. Also, cortical spreading depression (CSD), originally described by Leao and now thought to be the mechanism of the aura in migraine, may result in local ionic and chemical changes that might sensitize perivascular trigeminal fibers that set off a cascade of changes to produce the clinical symptomatology of migraine with aura by way of the simplified scheme above.9 Included in this process, trigeminal neural impulses may subsequently “feed back” through various routes to the meninges leading to local release of neuropeptides (e.g., CGRP, substance P, and VIP) that can amplify and sustain the headache cascade, perhaps influencing the development of cutaneous skin hypersensitivity (allodynia) seen in some patients and perhaps also setting the stage for the development of a chronic headache pattern. Stimulation of nearby brainstem nuclei by this cascade may also explain some of the associated constitutional symptoms that are commonly seen in migraine.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

While most patients with dangerous headaches are treated in the ED, the psychiatrist who is familiar with the presentation of rare headache syndromes may be a life-saver. A host of conditions need to be considered when an individual complains of a headache. Differentiating among all potential causes of headaches can be daunting. The task can be made less difficult by ruling out dangerous causes of headaches (Table 77-3). Once this has been done the clinician can match the headache history to the headache syndrome.

AVM, Arteriovenous malformation; ICP, intracranial pressure; LP, lumbar puncture; N/V, nausea and vomiting; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Because the clinical features vary for the different causes of headache, taking the headache history is the most crucial aspect of the workup (Table 77-4).6 Identification of the life-threatening causes of headache can usually be done with a thorough history. Elucidation of such features of the pain as timing (e.g., acute or chronic), onset (e.g., sudden or insidious), duration, severity, location (e.g., unilateral, bilateral, including the neck or eyes), associated symptoms (e.g., visual changes, motor symptoms, nausea, diaphoresis, and anxiety), body position (e.g., after standing up or lying down), and setting (e.g., during sleep, at work, or after exercise) is important. The effects of medication, meals (including specific foods [such as chocolate]), substances (such as caffeine and alcohol), sleep, and exercise also offer important clues to the diagnosis. A family history of certain types of headaches may also shed light on the etiology. For patients with more than one type of headache, a separate history should be obtained for each type.

Table 77-4 Eliciting History: Questions to Ask Patients about Headaches

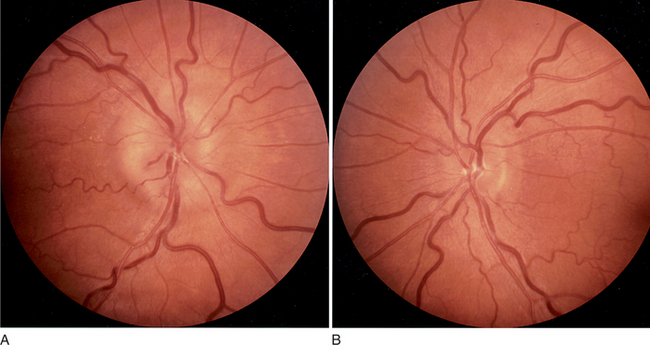

Physical examination of a patient with headache must include a full neurological examination, a funduscopic examination, and an examination of the head. Vital signs must also be assessed (as low or high blood pressure may be contributing factors). A fever may point toward a central nervous system (CNS) infection. The neurological examination will reveal any focal findings that may indicate a stroke or multiple sclerosis (MS). The funduscopic examination will search for signs of raised intracranial pressure (ICP), manifest by papilledema (Figure 77-2).14 Physical examination of the head will search for signs of trauma, and one should palpate for tenderness or masses, and listen over the temples and eyes for bruits that may signal the presence of an arterial-venous malformation. The neck must also be checked for rigidity.

Further testing may be indicated to evaluate etiologies suggested by the history and physical examination (Table 77-5). Imaging may be needed if a brain mass, stroke, or MS is suspected. Computed tomography (CT) scans are usually quicker and cheaper whereas magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more sensitive and expensive. A lumbar puncture (LP) can help evaluate infectious etiologies, subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), or ICP. In an elderly person with new-onset headache, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) suggests giant cell arteritis or temporal arteritis. Electroencephalography (EEG) and evoked responses have no particular role in primary headache diagnosis but may be helpful in sorting out several of the secondary headache causes.

Table 77-5 Ordering Laboratory and Other Tests

| Suspected Condition | Order |

|---|---|

| Acute stroke or bleed | CT |

| Aneurysm | MRA or CT angiogram |

| CVT | MRI and MRA or CT and CT angiogram |

| MS | MRI |

| Infection | LP |

| Temporal arteritis | ESR, CRP |

| Seizures | EEG |

| Carbon monoxide poisoning | Carboxyhemoglobin |

| CNS tumor | CT |

| Pheochromocytoma | 24-Hour urine metanephrine; abdominal CT |

CNS, Central nervous system; CRP, c-reactive protein; CT, computed tomography; CVT, cerebral venous thrombosis; EEG, electroencephalogram; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; LP, lumbar puncture; MRA, magnetic resonance angiogram; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MS, multiple sclerosis.

HEADACHE “RED FLAGS”

Historical features that may indicate a dangerous underlying cause for headache include the so-called “first and worst” headache, that is, the sudden onset of a de novo severe headache, possibly indicating an SAH often as a result of an aneurysmal bleed. Also known as a “thunderclap headache,” this pattern has been investigated in some detail, and there is a differential diagnosis beyond SAH, with both primary and secondary types described (Table 77-6). Some of these headaches are actually of benign origin with a negative evaluation; however, given the risks involved in missing an aneurysmal bleed, this pattern cannot be assumed to be benign and must be evaluated.

Headache associated with fever, chills, and change in mental status is of evident concern and not often confused with a primary headache syndrome. Similarly, a new-onset headache in a compromised individual (e.g., someone with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS]) or in someone with a concerning past medical history (e.g., with metastatic cancer) should also prompt concern.

TREATMENT

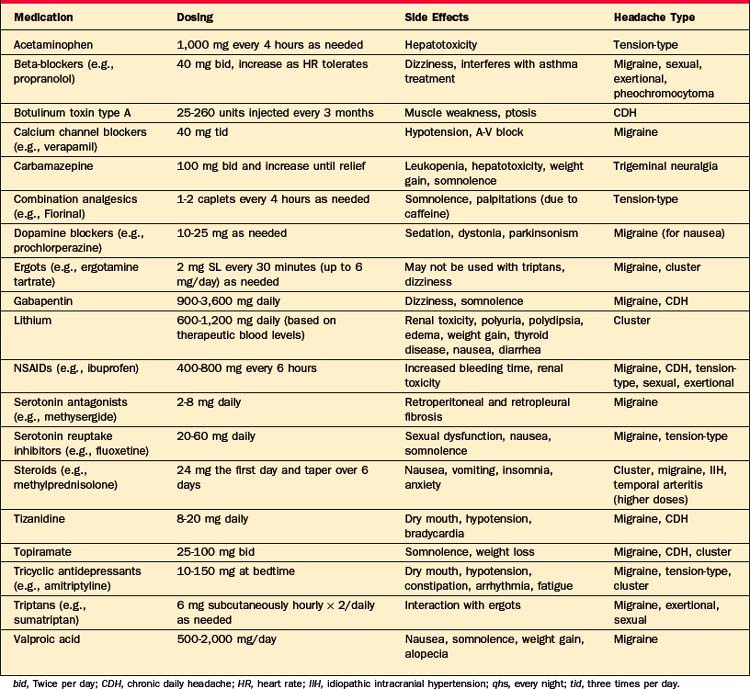

Specific treatment of headache depends on the underlying cause (see next section, Headache Syndromes: Clinical Features, Diagnosis, and Treatment), but some general rules apply. Symptomatic treatment of most types of headache begins with analgesics (such as acetaminophen and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]), and many medications can be used for multiple types of headaches (Table 77-7). Opiates are generally discouraged in the treatment of headaches, although for severe pain in a postsurgical setting they may be helpful in the short-term. In the treatment of chronic daily headaches, opiates have been unsuccessful, with nearly three-quarters of patients either lacking marked improvement or showing problematic drug behavior, such as dose violations.

HEADACHE SYNDROMES: CLINICAL FEATURES, DIAGNOSIS, AND TREATMENT

Primary Headaches

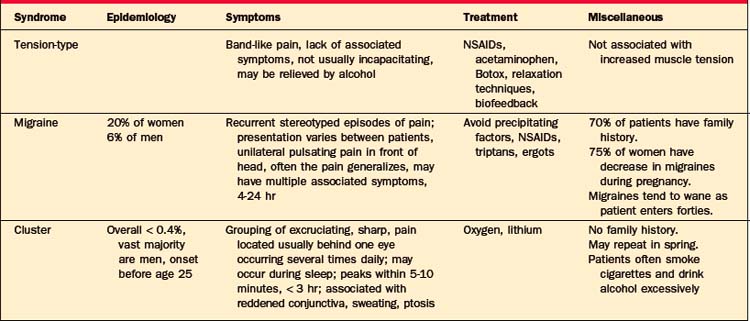

Most headaches are primary headaches: tension-type, mi-graine, or cluster headaches (Table 77-8). These are chronic recurring headaches for which there is no apparent structural abnormality.

Tension-Type Headaches

The designation may be a misnomer as recent studies have demonstrated that this type of headache is not reliably associated with increased muscle contractions or physiological tension.1 The mechanism of the headache may be related to hyper-excitability of afferent neurons from muscle or impairments in pain inhibitory systems. Tension-type headache is somewhat more common in women than in men. Pain is generally the main complaint; there is little associated photophobia, phonophobia, or hyperacusis.1 Nausea may be a complaint as well, but vomiting is rare.1 Patients usually describe the pain as bilateral, band-like, steady, and mild to moderate in intensity. Increased tenderness in the muscles of the head and the frontal, temporal, masseter, pterygoid, sternocleidomastoid, splenius, and trapezius muscles can sometimes be demonstrated with palpation using the second and third digits,4 but its absence does not rule out the disorder. Researchers may use a palpometer to measure muscle tenderness. Most patients can continue to function with tension-type headaches.

Treatment of tension-type headaches consists of reassurance and advice about treatment. Simple analgesics are used to treat individual headaches. The best evidence of effectiveness is for aspirin in doses of 500 to 1,000 mg; acetaminophen is less effective.15 Opioids and barbiturate-containing medications should be avoided as tolerance can develop with their use, which may lead to escalating doses and to dependence.

Prophylactic treatment is needed when headaches are disabling or frequent. Good evidence supports the use of amitriptyline, which is generally effective for headaches (used at doses lower than those needed to treat depression).16 Tizanidine may also be useful.16 Mirtazapine has also been shown to be effective.17 Open-label studies have suggested a possible benefit for botulinum toxin injections into the head and neck, but placebo-controlled trials show no benefit.16 Some evidence supports the use of biofeedback-assisted relaxation techniques, but evidence is lacking to support the use of physical therapy or acupuncture.

Migraine

Migraine headaches have been classified as vascular headaches, although recent evidence suggests that dysfunction of neurotransmitter systems (e.g., substance P, neurokinin A, and serotonin) are involved in the pathophysiology.5 Migraines are more common in women (occurring in up to 20% of women). The female-to-male ratio for migraines is 3:2. These headaches tend to run in families, with 70% of patients having a family history of migraines.5 Migraine symptomatology may be complex, but for an individual patient, headaches occur in a recurrent stereotyped manner.1 Migraine usually causes a unilateral pulsatile pain in the frontotemporal region or around the eye. In half of patients, the pain eventually spreads to both sides of the head.1 The pain may become dull and symmetrical, similar to that of a tension-type headache. Photophobia and phonophobia are common features. Autonomic dysfunction arises and includes slowed gastric emptying, nausea, and vomiting that can cause severe disability. The length of a headache can be greatly variable, but it usually lasts from 4 to 24 hours. Migraines may be precipitated by ingestion of certain foods (e.g., aged cheese, red wine, chocolate, and nuts), by skipping meals, by too little sleep, by too much sleep, and by psychological stress. Often, the weekends or the start of a vacation can precipitate a migraine.1 In women, migraines often begin at menarche and recur premenstrually. Contraceptive medication may worsen migraines in some women, while in others it may improve symptoms. Pregnancy offers relief from migraines in about three-fourths of women.1 Migraine symptoms often improve when patients reach their thirties and forties. Nocturnal migraines arise during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.1

Common migraines are those without an aura, while the classic migraine (which occurs in only about 15% of migraine sufferers) is preceded by an aura, usually a visual change (such as a field cut or scotoma, or flashing zig-zag lines [scintillations]).1 Auras (any transient neurological alteration) typically evolve over several minutes and can last up to an hour. Hallucinations (e.g., visual, olfactory, auditory, or gustatory), motor deficits (e.g., hemiparesis or hemiplegia), paresthesias (e.g., of the lips and hands especially), aphasia, perceptual impairments, anxiety, and depression are varieties of migraine auras.1 On rare occasions an aura may not be followed by a headache and it can mimic other neurological disorders (e.g., stroke, psychosis, or intoxication).1

Several theories to account for migraines have been discussed earlier in this chapter. In addition, symptoms of aura have been shown to coincide with decreases in regional cortical blood flow corresponding to the localization of neurological symptoms.5 Recent investigations have revealed that activated C-fibers release neuropeptides (such as substance P and neurokinin A), which then generate an inflammatory response within the meninges; this prolongs a headache.5 Other messenger systems involving nitric oxide and calcitonin gene–related peptide are also likely involved.5 In addition to this peripheral sensitization, there are likely central processes at work during headaches (such as the recruitment of previously non-nociceptive neurons).12 The painful nature of usually benign activities or stimuli (such as coughing) during a headache may be an example of this central sensitization.

Chronic Daily Headache

This term describes a fairly frequent clinical syndrome arising from a number of conditions all having in common the production of headache in an individual for 15 days a month or more. This pattern may begin de novo (new daily persistent headache) or as an unusual primary headache (hemicrania continua), but it is more commonly thought to reflect a transformation of migraine (a chronification of tension-type headache).1 Management is a challenge, and these patients make up the bulk of referrals in most headache clinics. Often with the daily presentation the actual headache characteristics become more drab, and less dramatic and distinct, compared with the intermittent migraine pattern. Prevention of this complication is one of the goals of early aggressive headache management. Other features of this headache type are as discussed earlier in this chapter.

Cluster Headaches

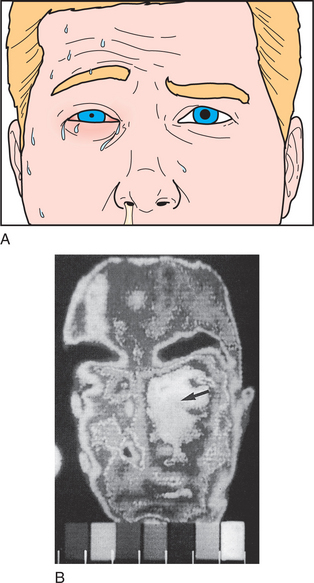

Cluster headaches are less common than are migraine or tension-type headaches; they are estimated to have a prevalence of less than 0.4%.6 The male-to-female ratio with cluster headaches is at least 5:1.6 There is usually no family history of such headaches.6 Risk factors include smoking and excessive alcohol intake. The onset is usually before age 25 and it may have a cyclical pattern that repeats in the spring. Cluster headaches often occur during REM sleep.1 The syndrome is named for the grouping of headaches—one to eight times daily for several weeks—with periods of month to years without headaches. The pain peaks within 5 to 10 minutes and can last up to 3 hours. The pain is strictly unilateral, described as sharp, excruciating, and non-throbbing, located around or below one eye or temporal region. Autonomic dysfunction manifests as injected conjunctiva, profuse sweating, facial flushing, ptosis, or miosis (Figure 77-3).1,9 Headaches may be triggered by the use of alcohol or tobacco.

Cluster headaches may be aborted by breathing 100% oxygen for 15 minutes.12 Vasoconstrictive medications and triptans are also helpful. Ergotamine tartrate 2 mg sublingually (SL), repeated every 30 minutes up to 6 mg in 24 hours, is advised. A steroid burst (such as a medrol dose pack) can also help. Choices for prophylactic medication include verapamil and lithium. Successful dosing for lithium is based on blood levels in the therapeutic range for the treatment of bipolar disorder. Response usually takes 3 weeks. Topiramate 100 mg twice a day has also shown some efficacy.18

Other Primary Headache Syndromes

Rarely, individuals develop sudden, severe headaches that begin with orgasm. Clearly, the clinician must exclude dangerous causes of secondary headaches, such as SAH or headaches due to a rise in ICP. Severe pain continues for more than 2 hours in one-fourth of patients and for as long as 24 hours in some.19 Orgasms cause a release of vasoactive substances (including serotonin, neurokinins, and catecholamines) that may cause vascular changes leading to pain. Treatment of orgasm-induced headaches includes long-term prophylaxis with propranolol. Triptans or indomethacin (25 to 100 mg) taken 30 minutes before initiation of sexual activity has also been effective in preventing headaches.19

Primary exertional headache is a pulsating headache that develops only during or after exercise. It can last 5 minutes to 48 hours.19 As with sexual headaches, dangerous causes of headache are important to exclude. Indomethacin and triptans have been helpful in preventing these types of headaches.19

SECONDARY HEADACHES

Structural causes should be evaluated if the patient’s headache pattern does not follow that of one of the primary headache syndromes, is accompanied by an abnormal neurological examination, is progressive, or is of acute onset. Discussed below are some of the dangerous causes of headache; they include trauma, cerebrovascular accidents, infections, and tumors. We will also discuss other common causes of headache (such as trigeminal neuralgia, temporal arteritis, and medication overuse headaches).

Posttraumatic Headache

Headache develops in over 80% of patients after head trauma.3 Nearly half of those who have suffered a concussion have headaches that last for up to 2 months after the injury.20 Headaches after trauma may be due to a number of factors, including acceleration and deceleration forces that can cause shear injury to neurons. Psychological, social, and medicolegal issues may also play a role. Nausea, vomiting, dizziness, vertigo, depression, and anxiety can accompany the headaches. The headaches often begin within 2 weeks of the injury and may resemble migraine or tension-type headaches.

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

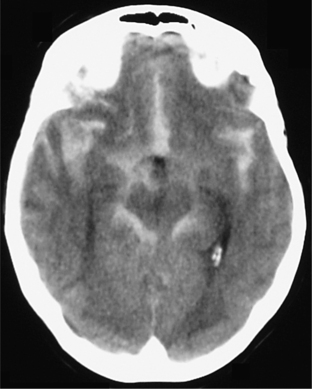

A “thunderclap headache” is the classic description of the presentation of SAH, but there are other causes of an excruciating and sudden headache (see Table 77-6). SAH is caused by rupture of the wall of a cerebral aneurysm or of a cerebrovascular malformation (Figure 77-4).9 The fatality rate with SAH is nearly 50%, and half of the survivors have severe deficits.3 The most common site of such a rupture is the circle of Willis. The sudden onset (reaching its peak within a minute) of a severe headache is the most common presentation, and it is often associated with nuchal rigidity. SAH often occurs during exertion (e.g., exercise, sexual intercourse, or straining on the toilet). Initially, there may be fever, nausea, vomiting, seizures, lethargy, and even coma. Focal neurological deficits and retinal hemorrhages point toward SAH. Diagnosis can usually be made on seeing blood on a noncontrast CT or in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) during an LP. Occasionally, SAH may be the result of vascular leaks from the pathological vessel, or sentinel bleeds, and the presentation is not quite as dramatic. At times no cause can be found to explain a documented SAH and in these patients the prognosis appears to be benign. Risk factors for SAH include head trauma, thrombocytopenia, use of warfarin or heparin, clotting factor deficiency, cocaine use, and ingestion of tyramine while taking a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI). Treatment of SAH and intracranial bleeds depend on their etiology, location, and symptoms. Neurosurgery consultation is indicated for larger bleeds that may cause compression and herniation. Evacuation of the bleed may be considered. Supportive care includes prevention of increases in ICP that may cause herniation, while avoiding hypotension that could cause ischemia. Use of the calcium channel blocker nimodipine improves outcomes in SAH.

Aneurysm

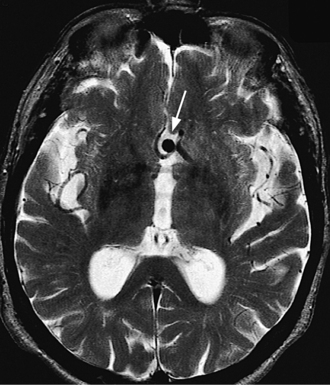

Headache, likely attributed to either sentinel bleeds or local compression, is present in 18% of those with an unruptured cerebral aneurysm3 (Figure 77-5).21 This can be an important and potentially life-saving warning considering the morbidity and mortality rates of SAH. The classic presentation of an enlarging posterior communicating cerebral artery aneurysm is severe posterior orbital pain associated with third nerve palsy and a blown pupil. Between 2% and 9% of autopsies reveal Berry aneurysms; half of them are detected in the circle of Willis.22

Intracranial Mass Lesions

Brain tumors and subdural hematomas (SDHs) may cause headaches that initially may be confused with tension-type headaches when the headache symptoms are mild, bilateral, and dull. They may worsen as ICP rises while coughing, straining, or bending over, or during REM sleep. Objective evidence of increased ICP (such as papilledema) may not be evident until late in the course. Similarly, localizing findings on neurological examination may not be apparent, though subtle cognitive and personality changes are usually seen. Chronic SDH can be a cause of a fluctuating headache accompanied by confusion and lethargy (Figure 77-6).21 Headache is found in over 80% of those with chronic SDHs.3 SDHs develop more commonly in the elderly, in those who are anticoagulated, and in alcoholics. Brain tumors are also seen more in those over age 50.

Ischemic Stoke

Seventeen percent to 34% of patients with ischemic stroke complain of headache.3 The presence of focal neurological deficits helps differentiate the headache of a stroke from primary headaches. The pain is usually mild to moderate. The complaint of headache is more often seen with basilar territory than carotid strokes.

Cerebral Venous Thrombosis

Thrombosis of the cerebral veins and sinuses causes swelling of cerebral veins and reduces absorption of CSF. The increased pressure in the skull leads to infarcts and to hemorrhages. The condition can be fatal. Headache is the most common symptom of cerebral venous thrombosis occurring in over 90% of cases and is often the initial complaint.23 In 90% of cases additional neurological symptoms (such as seizures, encephalopathy, papilledema, or focal deficit) develop.3 Cerebral venous thrombosis is more likely to affect young adults and children. In adults, 75% of cases are women, and are exacerbated by use of hormonal contraception, head trauma, or ear and sinus infections.23 Treatment usually involves anticoagulation with heparin in the hospital and oral anticoagulation for an extended period as an outpatient.

Pheochromocytoma

Fifty percent to 80% of those with pheochromocytomas have paroxysmal headache with or without elevated blood pressure.3 The headache from pheochromocytoma can be frontal or occipital and may be constant or pulsating. The headache is associated with other symptoms of increased catecholamines: sweating, flushing, anxiety, paresthesias, and chest or abdominal pain. The episodes last less than 15 minutes in half of patients and last less than an hour in 70%.3 The diagnosis is made with a 24-hour urine collection that measures the catecholamine breakdown product, metanephrine. Treatment is usually surgical removal of the adrenal tumor. Alpha- and beta-blockers are used preoperatively to control symptoms.

Acute and Chronic Meningitis

Acute meningitis manifests as a severe, rapid-onset headache associated with fever, neck stiffness, photophobia, and malaise. This condition often occurs as an epidemic in young adults in areas of relative confinement (such as military barracks or college dormitories). Acute meningitis is usually caused by Meningococcus or Pneumococcus.1

Chronic meningitis causes a continuous dull headache, accompanied by signs of systemic illness, typically with cognitive decline. Chronic meningitis can cause irritation and compromise cranial nerve (CN) function (creating, for example, blurred or double vision [CN III, CN IV, and CN VI], facial palsy [CN VII], or hearing impairment [CN VIII]).1 An LP shows elevated white blood cells (WBCs), low glucose, and elevated levels of protein. Chronic meningitis is caused most often by Cryptococcus, but Lyme disease and fungal infections are also potential culprits. Having a compromised immune system (e.g., having AIDS, being elderly, receiving treatment with steroids) is a risk factor for the development of chronic meningitis.

Treatment of meningitis involves administration of the appropriate antibiotic and supportive care (including intravenous fluids, antipyretics, anticonvulsants, and bed rest) as needed. Nearly a third of patients suffer prolonged headaches (more than 3 months) after bacterial meningitis.1

Encephalitis

CNS infection causes headache through release of toxins by the infective agent, swelling of the brain, and meningeal irritation. Sporadic encephalitis is most often caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV), which has a predilection for the inferior surfaces of the frontal and temporal lobes.24 Herpes encephalitis commonly causes fever, confusion, somnolence, and, because of its localization to the temporal lobes, partial complex seizures and amnesia.1 An LP reveals elevated WBCs. HSV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of CSF makes the diagnosis in 95% of cases.3 An MRI may reveal inflammation of the inferior surfaces of the temporal and frontal lobes. Treatment is with acyclovir or valacyclovir. Other causes of encephalitis include arbovirus and mumps.1

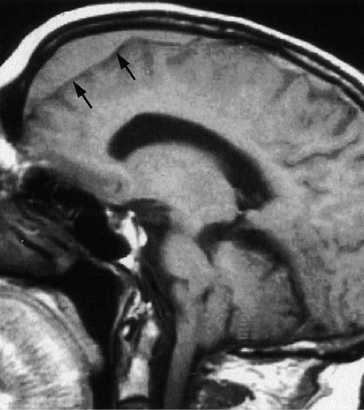

Temporal Arteritis

Temporal arteritis manifests almost exclusively in patients over age 55 years with a constant, but dull, headache over one or both temples. Jaw claudication (increasing jaw pain on chewing) is rare, but it was once considered pathognomic for the condition.1 In advanced cases, the temporal arteries can be red and tender (Figure 77-7).9 Often there are systemic signs (such as low-grade fever, malaise, and weight loss) and there may be joint pain or other signs of rheumatoid disease, and visual loss, including amaurosis fugax. Blindness as a result of ophthalmic artery occlusion and ischemia from cerebral artery occlusion can lead to serious and permanent complications. An ESR above 40 is present in over 90% of cases.1 An elevation of both ESR and C-reactive protein (CRP) has a specificity of 97%.25 A biopsy of the temporal artery that shows a focal granulomatous arteritis with giant cells is the definitive test, but is often unnecessary. Risk factors for temporal arteritis include age over 55 years and a history of polymyalgia rheumatica. Although the cause is unknown, the condition is associated with inflammation of the temporal and other medium to large cerebral and extracerebral arteries. Histologically, a focal granulatomatous arteritis with giant cells is seen. Temporal cell arteritis is treated with high-dose steroids to prevent blindness or other stroke syndromes. Prednisone (75 mg/day) should be initiated as soon as the clinical diagnosis is made.9 When symptoms have resolved and the ESR has returned to normal, prednisone should be tapered to 10 mg/day. The patient’s symptoms and ESR should be monitored closely for 1 to 2 years.

Trigeminal Neuralgia

Patients who suffer from trigeminal neuralgia, also known as tic douloureux, experience sharp pain along one of the three divisions of the trigeminal nerve, most commonly the V2 division.1 Stimulation of the affected area often triggers the pain. This can be by brushing the teeth, eating, touching the affected area, or drinking cold water. The pain is often described as “shocks” of severe pain that last 20 to 30 seconds; shocks do not occur during sleep. The pain begins after age 60, usually the result of a blood vessel pressing against the trigeminal nerve root as it emerges from the brainstem. Tumors of the cerebellopontine angle can also produce tic douloureux. The elderly and those with MS are more likely to suffer from trigeminal neuralgia. Carbamazepine is an effective treatment for trigeminal neuralgia,1 though surgery may be necessary to remove a tumor that presses on the trigeminal nerve. Injection of an anesthetic at the root of the trigeminal nerve can also stop the pain. Other options include placement of a barrier between an aberrant blood vessel and the trigeminal nerve root, as well as gamma knife lesions in the nerve root.1

Medication-Overuse Headaches

Frequent and consistent use of medications used for the treatment of pain can lead to chronic daily headaches. Such a pattern of use may disrupt the normal pain pathways that exacerbate headache syndromes. Perturbations in normal vasoconstriction may also contribute. Implicated medications include barbiturates, benzodiazepines, ergots, triptans, narcotics, and, least likely, NSAIDs.1 Evidence suggests that patients who overuse triptans experience medication overuse headaches faster and with lower doses than patients who use analgesics or ergots.26 Patients who overuse triptans are more likely to have daily migraine-like symptoms, while those overusing analgesics or ergots typically have daily tension-type headaches.26 Patients’ headaches rarely respond to preventive or prophylactic measures if the patient is overusing abortive treatments. If the patient is overusing narcotics, avoidance of opiate withdrawal may play a role in the medication overuse. Substance-withdrawal and medication-overuse headaches often need to be treated by tapering the substance or medication (or a similar substance) as an inpatient or outpatient detoxification. A short course of steroids (such as 60 mg of prednisone for 5 days) may also help. Up to 75% of patients improve when drug overuse is discontinued.4

CONCLUSION

Headache is a common complaint that psychiatrists hear from their patients. Despite their high prevalence, headaches can be disabling. Treatment of headaches depends on their etiology. While the comprehensive headache workup may be overwhelming, the patient can be best served by first ruling out the dangerous causes of headaches. Being familiar with the patterns of headaches will help the psychiatrist recognize and treat most headache syndromes (Table 77-9).27–33

| Cause | Comments |

|---|---|

| Carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning | CO, an odorless, colorless gas produced by the incomplete combustion of carbon-based fuel, contributes to approximately 5,000 to 6,000 accidental deaths per year. CO binds to hemoglobin with 200 times the affinity of oxygen, thus impairing cellular respiration. Exposure to CO causes cerebral vasodilation. Severe exposures are associated with tachycardia, dysrhythmias, seizures, myocardial infarction, and coma. During the winter, patients who live in poorly ventilated facilities develop mild symptoms of chronic low-level CO exposure (such as headache, nausea, and dizziness). The symptoms abate when the person is out of the house. Upper levels of normal for carboxyhemoglobin are 3% in nonsmokers and 10% in smokers.27 |

| Cervical spondylosis | Cervical spondylosis is seen in half of 50-year-olds and 70% of 70-year-olds, most often involving cervical vertebrae C6. Degenerative disease of the intervertebral discs and synovial joints may cause a compression of emerging spinal nerves. The pain can be referred to the occipital area, but it may also radiate to the front of the head. However, according to the International Headache Society (IHS), there is no association between cervical spondylosis and headache.3 |

| Cold-induced headaches | Exposure of the head, or passage of a cold substance on the soft palate, can cause a sudden band of pain across the forehead that peaks within a minute. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography has revealed decreased mean flow velocities in the middle cerebral artery in two patients experiencing the so-called “ice cream headache,” compared to a control who did not experience a headache after eating ice cream.28 Vasoconstriction is theorized to be important to the pathogenesis. Ice cream headaches stop within 2-5 minutes of removal of the cold substance. Similar headaches have been reported with cold exposure and cryosurgery. |

| Earache | Pain in the ear is most often the result of acute infection of the outer ear canal or the middle ear. Ear pain, however, can be referred to other areas of the head because small sensory branches from the mandibular, facial, vagus, and upper cervical nerves reach the outer ear. The epithelium of the inner ear is innervated by the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves. |

| Hemodialysis headache | Cerebral edema during dialysis may cause headaches usually described as a mild to moderate bilateral headache of a pressing/tightening quality that begins during hemodialysis. In some patients, the headache progresses to a more severe throbbing headache associated with symptoms of both migraine and tension-type headaches.3 Restlessness accompanying the headache may represent what some authors have called the dialysis disequilibrium syndrome.29 Other features of the syndrome include nausea, emesis, blurring of vision, myoclonus, confusion, and seizures. Hemodialysis headache usually abates within 2-5 hours. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors have been proposed as helpful. Caffeine-withdrawal headaches may be precipitated by dialysis as caffeine is removed. |

| Hypothyroidism | Hypothyroidism is more common in women and those taking lithium. The mechanism of headache is unknown. Thyroid hormone replacement is the treatment. |

| Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) | IIH, also known as pseudotumor cerebri or benign intracranial hypertension, is manifested by a headache in 75%-95% of patients. The pain is a dull, generalized headache that worsens with coughing or straining. Women of childbearing age are at risk for IIH; it has an annual incidence of 21 in 100,000. Irregular menses are often reported. Papilledema is out of proportion to symptoms. Typically there are no mental status or personality changes, though visual deficits and sixth nerve palsy may be seen. Persistent papilledema can lead to blindness. An LP may show an opening pressure over 400 mm H2O, though > 250 mm H2O is considered elevated in obese individuals (> 200 mm H2O is the cutoff in the nonobese). An MRI must be done to rule out other causes of increased ICP, such as a mass or SVT. Cerebral edema and decreased absorption of CHF are hypothesized to contribute to the cause of IIH. The headache of IIH responds to serial LPs. Weight reduction can also lower ICP. Medications (such as diuretics or the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, acetazolamide [starting at 200 mg bid and increasing to 1000-1250 mg/day]) can reduce ICP as well. Topiramate, an anticonvulsant that inhibits carbonic anhydrase, has been associated with weight loss and may be beneficial. A short course (2-6 weeks) of steroids (up to 1 mg/kg) may be necessary in severe cases. Shunt placement is reserved for refractory cases.30 |

| Lumbar puncture (LP) headache | The removal of CSF during an LP causes headaches, perhaps due to the reduction in the brain’s protective fluid. The pain is worse when sitting up or turning the head rapidly. There may be accompanying neck pain or nausea. The patient should lie down and the LP site should be checked for leakage. |

| Medication-induced headaches | Various medications may cause or exacerbate headache syndromes. Nitric oxide (NO) donors (the so-called “hot dog headache”) such as isosorbide dinitrate, nitroprusside, and nitroglycerine, likely because of their vasodilating properties, can cause headaches.3 Cytokines used in the treatment of immune dysfunction and cancers commonly cause headaches associated with other symptoms of systemic illness (e.g., malaise, irritability, and muscle aches). Commonly prescribed psychiatric medications that are most often associated with headaches are atropine, buspirone, cyclosporine, disulfiram, gabapentin, lithium, naltrexone, nicotine, stimulants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).31 Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) in combination with certain foods or medications can cause headaches that indicate a dangerous hypertensive crisis or cerebral hemorrhage. |

| Myofascial pain | Inflammation of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles can produce occipital pain, especially when tender nodules within the muscles are compressed. |

| Positional headaches | Orthostasis often causes headaches that occur on arising, and progressively worsen during the day; they are relieved by lying down. Accompanying complaints often include nausea, vomiting, dizziness, photophobia, tinnitus, anorexia, and malaise. Head-shaking and jugular compression often worsen the symptoms. Medication-induced orthostasis is the most common cause, but SDH, SAH (with vasospasm), third-ventricle colloid cysts, and sinus disease are other causes.3 Patients who are taking medications (such as tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs], antipsychotic drugs, and antihypertensive medication) that block alpha1-adrenergic receptors are at risk for orthostasis and for positional headaches. |

| Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) | PRES is a rare radiological finding. MRI scans show evidence of bilateral posterior cerebral edema. The syndrome is associated with medical illness, including hypertensive encephalopathy, eclampsia, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and treatment with immunosuppressive agents.32 |

| Sinus disease | Maxillary sinusitis is a common cause of facial or head pain. Acute sinusitis manifests with cough, purulent nasal discharge, and sinus tenderness. A fever may be present. Acute sinusitis can manifest as a thunderclap headache.33 |

| If symptoms are prolonged, a chronic sinusitis may be diagnosed. For some chronic sinusitis infections, endoscopic surgery may be necessary to clear passages. | |

| Systemic illness | Headache is often a symptom of systemic illness, such as influenza or sepsis. There are usually other signs and symptoms of the sickness syndrome, including fatigue, fever, nausea, and cough. The headache improves as the underlying illness resolves. |

1 Kaufman DM. Clinical neurology for psychiatrists, ed 5. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2001.

2 Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, et al. Lost productive time and cost due to common pain conditions in the US workforce. JAMA. 2003;290(18):2443-2454.

3 International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders. 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(suppl 1):1-150.

4 Welch KMA. A 47-year-old woman with tension-type headaches. JAMA. 2001;286(8):960-966.

5 Siow HC, Silberstein SD. Migraine. In: Schiffer RB, Rao SM, Fogel BS, editors. Neuropsychiatry. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.

6 Baldassano C, Stern TA. The patient with headache. In Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, editors: Massachusetts General Hospital guide to primary care psychiatry, ed 2, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

7 Wiendels NJ, Knuistingh Neven A, Rosendaal FR, et al. Chronic frequent headache in the general population: prevalence and associated factors. Cephalgia. 2006;26:1434-1442.

8 Wiendels NJ, van Haestregt A, Knuistingh Neven A, et al. Chronic frequent headache in the general population: comorbidity and quality of life. Cephalgia. 2006;26:1443-1450.

9 Lance JW, Goadsby PJ. Mechanism and management of headache, ed 7. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2005.

10 Low N, Singleton A. Establishing the genetic heterogeneity of familial hemiplegic migraine. Brain. 2007;130(2):312-313.

11 Gordon CD. Cluster headache and other autonomic cephalgias. In: Loder EW, Martin VT, editors. Headache. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians, 2004.

12 Cutrer FM, Bhasin P. Headache. In Ballantyne J, editor: The Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of pain management, ed 2, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

13 Brenner GJ. Neural basis of pain. In Ballantyne J, editor: The Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of pain management, ed 2, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

14 Friedman DI. Headache. In: Schapira AHV, Byrne E, editors. Neurology and clinical neuroscience. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2007.

15 Steiner TJ. Evaluation and management of headache in primary care. Expert Rev Neurother. 2004;4(3):425-437.

16 Mathew NT. The prophylactic treatment of chronic daily headache. Headache. 2006;46(10):1552-1564.

17 Bendtsen L, Jensen R. Mirtazapine is effective in the prophylactic treatment of chronic tension-type headache. Neurology. 2004;62:1706-1711.

18 Capobianco DJ, Dodick DW. Diagnosis and treatment of cluster headache. Semin Neurol. 2006;26(2):242-259.

19 Cutrer FM, Boes CJ. Cough, exertional, and sex headaches. Neurol Clin North Am. 2004;22:133-149.

20 Denninger JW, Norris ER, Samuels MA. Headache. In Stern TA, Herman JB, editors: Psychiatry update and board review, ed 2, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

21 Yock DH. Magnetic resonance imaging of CNS disease: a teaching file, ed 2. St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

22 Minyard AN, Parker JC. Intracranial saccular (berry) aneurysm: a brief overview. South Med J. 1997;90(7):672-677.

23 Stam J. Thrombosis of the cerebral veins and sinuses. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(17):1791-1798.

24 Aldea S, Joly LM, Roujeau T, et al. Postoperative herpes simplex virus encephalitis after neurosurgery: case report and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(7):96-99.

25 Eberhardt RT, Dhadly M. Giant cell arteritis: diagnosis, management, and cardiovascular implications. Cardiol Rev. 2007;15(2):55-61.

26 Limmroth V, Katsarava Z, Fritsche G, et al. Features of medication overuse headache following different acute headache drugs. Neurology. 2002;59:1011-1014.

27 Kao LW, Nañagas KA. Toxicity associated with carbon monoxide. Clin Lab Med. 2006;26:99-125.

28 Sleigh JW. Cerebral vasoconstriction may have a role. BMJ. 1997;315:609.

29 Alessandri M, Massanti L, Geppetti R, et al. Plasma changes of calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P in patients with dialysis headache. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:1287-1293.

30 Skau M, Brennum J, Gjerris F, Jensen R. What is new about idiopathic intracranial hypertension? Cephalalgia. 2005;26:384-399.

31 Levenson JL, editor. Textbook of psychosomatic medicine. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2005.

32 Kur JK, Esdaile JM. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome—an underrecognized manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(11):2178-2183.

33 McGeeney BE, Barest G, Grillone G. Thunderclap headache from complicated sinusitis. Headache. 2006;46(3):517-520.

Dodick DW. Chronic daily headache. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(2):158-165.

Murray CJL, Lopez AD. The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, anfactors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996.

Saper JR, Lake AEIII, Hamel RL, et al. Daily scheduled opioids for intractable head pain: long-term observations of a treatment program. Neurology. 2004;62:1687-1694.