CHAPTER 76 Seizure Disorders (Epilepsy)

OVERVIEW

Epilepsy is defined by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) as a “condition characterized by recurrent (two or more) epileptic seizures, unprovoked by any immediate identified cause.” An epileptic seizure is “a clinical manifestation presumed to result from an abnormal and excessive discharge of a set of neurons in the brain.”1

BRIEF HISTORY

The first recorded challenge of this interpretation appears at about 400 b.c. in the Hippocratic text, “On the Sacred Disease,” in which the author wrote that epilepsy was a disease involving the brain. However, the brain was not considered to be the site of origin of all epileptic seizures. Galen and others believed that although epilepsy involved the brain, involvement of other systems of the body was not seen as a secondary effect, but as the source of seizures themselves. For example, eclamptic seizures were believed to originate from the uterus.2

John Hughlings Jackson carried out observations crucial to the development of modern epileptology in the 1860s. In “Study of Convulsions,” he noted a certain order in the onset and spread of unilateral convulsions and concluded that focal origin of seizures was due to local pathology of a particular region of the brain.3 In the 1950s, a second model was proposed by a Canadian neurosurgeon, Wilder Penfield. Penfield found that some of his epileptic patients had seizures in which the electroencephalogram (EEG) revealed bilateral and symmetrical patterns. He proposed the centrencephalic model of epilepsy in which seizures originated in the central area of the brainstem.4

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

Epilepsy is the most common neurological disorder after strokes. Its incidence varies widely from country to country, but is estimated to be between 40 and 70 per 100,000 person-years in developed countries. Incidence of epilepsy is high during infancy, decreases to adulthood, but increases with advancing age.5,6

Most structural brain lesions increase the risk for seizures and epilepsy. Known risk factors for epilepsy include head trauma, cerebrovascular diseases, brain tumor, congenital or genetic abnormalities, infectious diseases, alcohol/drug use, and dementia. The risk of seizures from marijuana use is unclear.5,7,8

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Basic Mechanism and Genetics

Epileptic seizures are caused by abnormal, repetitive firing of neurons. Although multiple etiologies may result in these discharges, it is believed that three key elements are con tributory: neuronal membrane and ion channel characteristics; reduced action of the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA); and increased excitation through excitatory circuits through glutamate or other excitatory neurotransmitters.9,10 Absence seizures are believed to involve an abnormality in the circuitry between the thalamus and the cerebral cortex.11

Certain epileptic syndromes, both partial and generalized, follow single gene mendelian inheritance genetics. Since 1995, genetic discoveries have linked idiopathic epilepsies to mutations of voltage-gated channels, ligand-gated ion channels, and neurotransmitter receptors.12 Many other epilep-sies with genetic predispositions are likely due to complex multiple-gene inheritance patterns, and targeted pharmacological strategies have not yet emerged from these findings.

Pathology

Hippocampal sclerosis is the most common cause of recurrent partial epilepsy in adults. This is characterized macroscopically by shrinkage and induration, and histopathologically by pyramidal neuron loss and gliosis, most severely found in certain subregions of the hippocampus.13 Hippocampal sclerosis can be seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, and the presence of this abnormality portends good outcomes after epilepsy surgery in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE).

Malformation of cortical development is the most common structural pathological abnormality seen in pediatric epilepsy. Malformation may occur during neuroglial proliferation (e.g., as in cortical dysplasia), migration (heterotopia), or organization (polymicrogyria) of the cortex.14 These conditions are frequently associated with severe seizures and with developmental delays.

CLASSIFICATION OF SEIZURES AND EPILEPSIES

Classification of Seizures

The ILAE broadly classifies epileptic seizures into two groups (Table 76-1)15: focal (partial) seizures (i.e., those with an initial onset limited to one part of the brain); and generalized seizures (i.e., those with no discernible focus of onset). A third category consists of seizures that cannot be classified in these two categories.

Table 76-1 Clinical and Electroencephalographic Classification of Epileptic Seizures

Modified from Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy: Proposal for revised clinical and electro-encephalographic classification of epileptic seizures, Epilepsia 22(4): 489-501, 1981. Raven Press LTD, New York. © International League Against Epilepsy.

Classification of Epileptic Syndromes

An epileptic syndrome is an “epileptic disorder characterized by a cluster of signs and symptoms customarily occurring together” (Table 76-2).16 Epileptic syndromes are defined by a variety of characteristics, including the types of seizures encountered and the findings on the EEG and on neuroimaging tests. Syndromes are classified into localization-related (or focal, partial) epilepsies, generalized epilepsies, special syndromes, and epilepsies that do not fall into the preceding groups.

Table 76-2 The International Classification of Epilepsies and Epileptic Syndromes

Modified from Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy: Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes, Epilepsia 30(4):389-399, 1989. Raven Press LTD, New York. © International League Against Epilepsy.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATION OF SEIZURES

Generalized Seizures

Once the tonic stage ends, the patient enters the clonic phase, which is characterized by rhythmic jerking movements. Clonic movements have a high amplitude and a low frequency, unlike myoclonic movements, which are very brief, or tremors, which have a low amplitude and high frequency. In a generalized seizure, clonic movements are symmetrical, with the arms and legs moving in unison. Clonic arm movements generally have greater amplitude than clonic leg movements, and the trunk is usually uninvolved.

Partial Seizures

Simple Partial Seizures

Auditory seizures are produced by discharges in the anterior transverse temporal gyrus (Heschl’s convolution) and the superior temporal convolution. The patient reports tinnitus typically in the form of hissing, buzzing, or roaring sounds. Visual seizures, produced by discharges from the occipital focus, take the form of flickering lights or flashing colors (usually red or white), and are distinct from the “zig-zag” pattern of light sometimes reported by patients experiencing migraine. It is worth noting that nearly all epileptic patients have migrainous headaches and many migraine sufferers have abnormal EEGs. Despite the overlap between these two conditions, the visual features just described can help one distinguish migraines from simple partial seizures due to epilepsy.

SELECTED EPILEPSIES AND EPILEPTIC SYNDROMES

Temporal Lobe Epilepsy

TLE is the most common form of focal epilepsy in adults. Complex partial seizures arise from the mesial temporal region, for example, from the hippocampus, the parahippocampal gyrus, or the amygdala. The most common etiological factor associated with mesial TLE is the occurrence of prolonged febrile convulsions in childhood, which may predate the onset of afebrile seizures by many years.17,18 Childhood febrile convulsions are relatively common and few patients develop TLE as a result of them. However, prolonged febrile convulsions have been documented in a majority of patients with mesial TLE. The exact mechanism by which prolonged febrile convulsions generate hippocampal sclerosis remains unclear. Chromosomal abnormalities have been found in some familial cases of mesial TLE.19

Hippocampal atrophy may be seen on high-resolution MRI scans. Positron emission tomography (PET) scans show reduced uptake in radioactive glucose on the side of the pathology. Afflicted patients are often intractable to medical management, but can be effectively treated with surgical resection. Pathology often shows evidence of hippocampal sclerosis (see Pathology).

Idiopathic Generalized Epilepsy

Idiopathic generalized epilepsy (IGE) encompasses a number of specific syndromes that likely overlap each other. Common features among them include generalized seizures (absence, myoclonus, or tonic-clonic seizures), a characteristic EEG pattern (generalized spike-wave discharges), a genetic predisposition, and an otherwise normal neurological development. Although these patients have structurally normal MRI scans, there may be increased amounts of nonspecific abnormalities.20 Childhood absence epilepsy is most commonly seen; brief absence seizures occur, at times with great frequency (up to hundreds a day), starting between ages 4 and 10. They show a characteristic 3-Hz spike-wave discharge on the EEG. They are well controlled with medications. Most but not all patients become seizure-free. On the other hand, juvenile absence epilepsy starts somewhat later, after puberty. Absences are not as frequent, GTC seizures occur more often, and they typically require life-long therapy. The most common IGE is juvenile myoclonic epilepsy in which myoclonic and GTC seizures are the predominant patterns. This syndrome also requires life-long therapy.

Status Epilepticus

Status epilepticus is defined by the ILAE as continuous seizure activity, or two or more seizures without full recovery of consciousness for greater than 30 minutes.21 However, the length of a seizure before becoming labeled as status epilepticus has been challenged, and 5 minutes is likely a more clinically relevant time frame.22 The mortality rate in status epilepticus is very high, and as such, it should be considered a true emergency. As such, the ABCs (airway, breathing, and circulation) of emergency management should be emphasized. Immediate treatment consists of administration of intravenous (IV) lorazepam (0.1 mg/kg IV) followed by a loading dose of a medication available in IV form (phenytoin, levetiracetam, phenobarbital, or valproic acid) (Table 76-3). If seizures do not cease, a second agent should be added, and preparation for intubation and subsequent administration of continuous high-dose suppressive agents (e.g., propofol, midazolam, or pentobarbital) as well as monitoring with an EEG should be considered. Neurology consultation will be required in all instances.

EVALUATION OF SEIZURE DISORDERS

Clinical Examination

Patients should always be examined after a seizure to detect any evidence of asymmetry (e.g., weakness or twitching that is more pronounced in one arm than in the other). Such evidence would indicate a focal, rather than a generalized, seizure. Although the physical examination is almost always normal, a few signs may provide clues to the diagnosis. Since patients with epilepsy often have a history of brain lesions at an early age, the physician should look for evidence of hemiatrophy. For example, if a patient is asked to place his or her hands palm to palm, you may find that one hand is smaller than the other. In partial complex seizures, the physical expression of an emotional response may be asym metrical (e.g., a smile is almost always one-sided). In about 80% of patients with asymmetrical emotional responses or reflexes, the responsible brain lesion is in the hemisphere opposite the weaker side of the body.

Electroencephalogram

All patients with a new seizure or suspected seizure dis-order should obtain an EEG. The sensitivity of an EEG is relatively low (ranging from 30% to 50%) in detecting epileptiform abnormalities on a single EEG, but the yield may be increased (to 80% to 90%) by obtaining multiple EEGs, an ambulatory 24-hour EEG, or a sleep-deprived EEG.23–26 Hyperventilation and photic stimulation (flashing lights) during the EEG may further increase the yield of the EEG in limited circumstances.

Neuroimaging

MRI is the imaging modality of choice in patients with seizures. In addition to major structural abnormalities (such as brain tumors, abscesses, and strokes), an MRI scan may reveal more subtle structural abnormalities (such as hippocampal volume loss and asymmetry), seen typically in patients with TLE.27 Computed tomography (CT) has a more limited role in patients not suspected of having trauma, intracranial hemorrhage, increased intracranial pressure, or other similar catastrophic etiologies.

Because of difficulties in accurately localizing focal seizures, multiple other imaging modalities are used to complement EEG and MRI scans in patients with a seizure disorder, particularly in patients undergoing surgical evaluation. These include PET,28 single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT),29 and magnetoencephalography.30

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Nonepileptic Psychogenic Seizures

Nonepileptic psychogenic seizures (“pseudoseizures,” “psychogenic seizures”) represent a large and challenging subgroup of patients evaluated for a seizure disorder. They may represent up to 30% of patients with seizures refractory to traditional antiseizure medications.31 Most frequently, these seizures are a form of conversion disorder in which the patient produces these seizures without conscious effort and without an obvious secondary gain. Patients with nonepileptic psychogenic seizures frequently have an antecedent history of sexual or other psychological trauma,32,33 and they are much more likely to be female.34

Although preexisting risk factors and description of seizures (such as pelvic thrusting34) can be helpful in raising suspicion of a nonepileptic psychogenic seizures, conclusive diagnosis usually requires the use of video-EEG monitoring during which a typical episode is captured. Hyperkinetic frontal lobe seizures may mimic nonepileptic psychomotor seizures,35 leading to substantial difficulties in reaching the correct diagnosis in a small portion of patients.

Although excellent outcomes have anecdotally been reported if an underlying psychiatric conflict can be identified and resolved, these are often difficult to identify, and no definitive treatment exists for this condition. More than 70% of patients continue to have seizures chronically,32,36 a considerably higher rate than with patients with epileptic seizures. Unlike prevailing beliefs, the number of patients with nonepileptic psychogenic seizures and epileptic seizures is low.37

Other Conditions Mimicking Seizures

A variety of other paroxysmal disorders may mimic seizures. Syncope may induce transient cerebral hypoxia and may produce seizure-like activity (such as myoclonic jerks, head turns, and automatisms) in more than 10% of patients.38–40 Syncopal attacks are more often associated with feelings of light-headedness, sweating, and nausea, and are seen after prolonged periods of standing.38 Although syncopal attacks are relatively benign, especially in young individuals, additional testing, including a cardiac evaluation, should be strongly considered.

Migrainous phenomena may often mimic seizures in that they may be manifest as auras of visual disturbances, vertigo, migrating paresthesias, and other sensory disturbances, and speech difficulties, all of which may also be seen in partial seizures. These migraines may occur without headaches; rarely, a migraine may evolve into a seizure.41 Panic disorder may frequently mimic simple autonomic seizures. Common symptoms of autonomic arousal include nausea, tachycardia, hyperventilation, palpitations, and shaking. Panic attacks typically last longer than simple autonomic seizures. Features of sleep disorders (such as cataplexy and hypnagogic hallucinations in narcolepsy, bizarre behaviors in parasomnias, and periodic limb movement disorders) may readily be mistaken for seizure disorders.42

THERAPY OF SEIZURE DISORDERS

Historical Notes

Despite this promising beginning nearly 2,000 years ago, the treatment of seizure disorders remained in the “Dark Ages” until relatively recently. The dramatic seizures and interictal behavioral changes, which are seen particularly in patients with complex partial seizures, may account for the fear and superstitions that have impeded the scientific study of epilepsy.

Medical Treatment Consideration

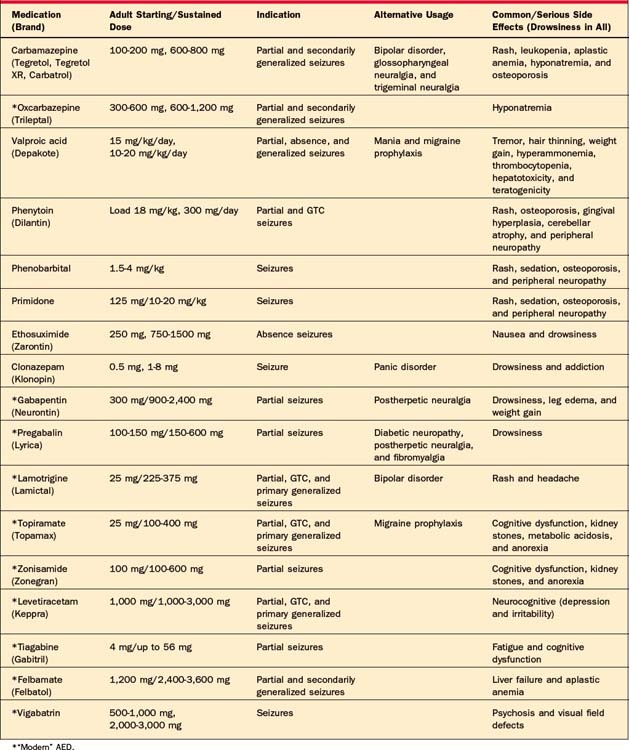

The most commonly used antiepileptic drugs are summarized on Table 76-4. The modern AEDs are not believed to be more efficacious in comparison to the “classical” AEDs, but they are likely better tolerated43; recent evidence suggests that the modern agents may be superior in some instances,44 while the “classical” drugs are preferable in other conditions.45

Basic treatment generally involves starting monotherapy with an AED and increasing its dosage until seizures are controlled or side effects become intolerable. If this occurs, monotherapy with a second medication should be considered; thereafter, a third medication or a combination of two should be considered. In most instances where medications will be effective, control will be achieved by the first or second medication initiated.46

The selection of AEDs, given the myriad of choices today, depends on multiple factors; it is not amenable to a dogmatic schema. Sometimes, one medication is clearly superior for a known seizure type (such as valproic acid for primary generalized seizures). Sometimes, an AED may aid in the treatment of concurrent medical conditions (such as lamotrigine for concurrent mood disorder or topiramate for headaches). More frequently, the effects of concurrent medical conditions (such as pregnancy or hepatic/renal failure) and the AEDs, as well as medication interactions, should be carefully evaluated (particularly in patients on chemotherapy). In patients who have had side effects (such as skin rashes or other allergic reactions to AEDs), the physician should select an AED with a more preferable side-effect profile.47 Especially with use of benzodiazepines, the addictive potential of an AED needs to monitored.

Surgery

Surgical management of epilepsy represents the only option for a cure for the 35% of patients with epilepsy who are intractable to medications.46 The greatest success has been achieved in patients with mesial TLE. A meta-analysis of these patients showed that two-thirds of patients were free of disabling seizures, and 85% had improved after surgery.48 A study that randomized patients for medical and surgical treatment revealed that patients who underwent surgery had both better control of their seizures and a better quality of life.49 Because of potential adverse effects on language and memory, and visual fields, in addition to the usual risks of vascular problems and infections, patients are carefully and thoroughly investigated by a multidisciplinary team involving neurologists, neurosurgeons, radiologists, neuropsychologists, and psychiatrists. In addition to the previously stated neuroimaging studies and standard EEGs, patients undergo an additional intracarotid sodium amytal (“Wada”) test,50 neuropsychological assessment, implantation with intracranial leads, and functional neuroimaging.

Surgery for extratemporal lobe epilepsy has been more challenging. Because the finding of a structural lesion is highly predictive of surgical success, neuroimaging has had a disproportionate importance in the evaluation of these patients. Even subtle cortical dysplasias may underlie refractory epilepsy or status epilepticus.51,52 More drastic surgeries (such as hemispherectomies or corpus callosotomies) may be performed for either curative or palliative purposes in severe epilepsy.

Vagus Nerve Stimulation

Although a relatively novel tool in the armamentarium of epileptologists, the antiepileptic effects of vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) have been known since the nineteenth century.53 VNS consists of a battery-powered coin-sized generator implanted in the chest that transmits pulses of electricity at regular intervals to the vagus nerve. The patient may provide additional stimulation at higher power with a hand-held magnetic device. Clinical trials have demonstrated that seizure frequency is reduced by at least 50% in up to one-third of patients.54 Contrary to use of medications, the effectiveness of the VNS appears to increase with time.55,56 However, few patients become seizure-free solely with VNS. Serious side effects are relatively rare, and common side effects (such as voice alterations) are well tolerated. Unlike the effects of medications, cognitive side effects of VNS are nonexistent. Some studies have shown that VNS is also effective for treatment-resistant depression.57

PSYCHIATRIC DISTURBANCES IN EPILEPSY

The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with epilepsy is high.

Depression

Depression is the most common co-existing psychiatric disturbance in patients with epilepsy, affecting up to 30% of patients, and likely a higher percentage in those with uncontrolled epilepsy.58,59 In patients with TLE, postictal depression that lasts for hours or days may occur.60 Transient postsurgical depression is seen in nearly half of patients undergoing temporal lobectomy.61 Depression occurs more commonly in patients with epilepsy than in neurologically normal subjects, although not necessarily more often than in persons with chronic neurological disease. More surprisingly, though, depression appears to be a risk factor for epilepsy, as studies have shown an increased incidence of depression before a first seizure.62 The existence of depression also predicts pharmacoresistance in epilepsy.63 Depression and epilepsy may share common neurobiological substrates (including serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine).62,64 Treatment of co-existing depression must be included in the comprehensive treatment of a seizure disorder.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the first-line treatment for depression in patients with epilepsy because of their low potential of lowering seizure threshold and the lack of interaction with the AEDs. Neither venlafaxine, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), nor mirtazapine, a norepinephrine agonist, appears to lower seizure threshold.65 Amoxapine, clomipramine, and bupropion should be avoided in patients with epilepsy. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and buspirone lower seizure threshold at higher doses.66

Psychosis

Psychosis may affect up to 7% of patients with epilepsy.58 Psychotic symptoms may occur during the ictal, postictal, or interictal phase,67 and are a common co-morbidity. Ictal psychosis is a rare phenomenon. Ictal and postictal psychosis are infrequent; a more common form is chronic interictal psychosis. An association of interictal psychosis with TLE has been suggested numerous times, but its relationship has yet to be elucidated. Psychosis related to epilepsy appears to have fewer negative symptoms and is more easily treated. A small number of patients may experience “forced normalization,” which describes the phenomenon in which periods of increased seizure activity alternate with periods of being seizure-free during which the patient has greater psychosis, despite normalization of the EEG.68

Certain psychotropic agents may lower the seizure threshold and even generate epileptic spikes on the EEG; these agents (including clozapine, chlorpromazine, and loxapine) should be avoided in patients with epilepsy. Haloperidol may carry the lowest risk of seizures; alternatives also include olanzapine, risperidone, and molindone.69 Surgical treatment of patients with TLE and chronic psychosis, with subsequent control of seizures, does not exacerbate psychosis by “forced normalization.”70 An adequate history is often sufficient to determine whether seizures and subsequent psychosis are due to chronic psychosis of epileptic disorders, or a manifestation of seizures due to psychotropic drugs.

Anxiety

The prevalence of anxiety in patients with epilepsy is high (ranging from 10% to 50%), but is more difficult to assess.71,72 Simple partial seizures may manifest as anxiety-like symptoms (e.g., fear and autonomic hyperactivity). Generalized anxiety disorder is most commonly seen in patients with epilepsy during the interictal period. Ideal treatment of interictal anxiety includes both nonpharmacological management (e.g., psychotherapy and stress reduction) and medications (e.g., SSRIs and benzodiazepines).

Memory

Subjective complaints of memory difficulty are a nearly universal complaint in patients with chronic epilepsy. Hippocampal damage is a known consequence of repeated convulsive seizures.73 It is likely that interictal epileptiform discharges detectable on the EEG cause progressive memory problems and cognitive dysfunction in patients with epilepsy.74 In addition, patients with chronic epilepsy are prescribed multiple antiepileptic medications, which further contributes to a decline in memory and cognition.

Interictal Personality Changes

Waxman and Geschwind75 described the following five personality changes associated with partial complex epilepsy: hypergraphia, hyperreligiosity, hyposexuality, aggressivity, and viscosity. The Russian author Fyodor Dostoyevsky is perhaps the best-known example of an epileptic with hypergraphia, which is the tendency to write prolifically.

Finally, some epileptic patients develop a personality trait Waxman and Geschwind75 called viscosity, meaning that the patients tend to be “sticky.” Some patients with TLE may call the physician every night, and, once they start talking, they will not stop. These five characteristic personality disturbances provide evidence that brain lesions can cause long-term changes in behavior.

SUPPORTIVE CARE AND LONG-TERM MANAGEMENT

The primary goal of reintegrating the patient with epilepsy as a productive member of society, both vocationally and socially, is not necessarily achieved by focusing on seizure control and treatment.76 Quality-of-life measures specifically tailored to the patient with epilepsy have been developed,77 and attention paid to individualized deficits in these types of measures will ultimately lead to greater patient satisfaction and medication compliance. Such comprehensive care of the patient requires a multidisciplinary approach, which, in addition to a neurologist, may include a psychiatrist, clinical social worker, and neuropsychologist.

1 Commission of Epidemiology and Prognosis. Guidelines for epidemiological studies on epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1993;34(4):592-596.

2 Temkin O. The falling sickness. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1971.

3 Jackson J. Selected writings of John Hughlings Jackson. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1931.

4 Penfield W, Jasper H. Epilepsy and the functional anatomy of the human brain. Boston: Little, Brown, 1954.

5 Sander J, Shorvon S. Epidemiology of the epilepsies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;61(5):433-443.

6 Hauser WAAJ, Kurland LT. Incidence of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures in Rochester, Minnesota: 1935-1984. Epilepsia. 1993;34(3):453-468.

7 Hauser WA, Kurland LT. The epidemiology of epilepsy in Rochester, Minnesota 1935 through 1967. Epilepsia. 1975;16:1-66.

8 Gordon E, Devinsky O. Alcohol and marijuana: effects on epilepsy and use by patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2001;42(10):1266-1272.

9 Prince D, Connors B. Mechanisms of interictal epileptogenesis. Adv Neurol. 1986;44:275-300.

10 Najm I, Moddel G, Janigro D. Mechanisms of epileptogenesis and experimental models of seizures. In: Wyllie E, editor. The treatment of epilepsy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.

11 Snead OC. Basic mechanisms of generalized absence seizures. Ann Neurol. 1995;37:146-157.

12 Berkovic SF, Scheffer IE. Genetics in human epilepsy. Curr Opin Neurol. 1997;10(2):110-114.

13 Babb T, Brown W, Pretorius J, et al. Temporal lobe volumetric cell densities in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1984;25(6):729-740.

14 Barkovich J, Kuzniecky R, Jackson G, et al. Classification system for malformations of cortical development. Neurology. 2001;57(12):2168-2178.

15 Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 1981;22(4):489-501.

16 Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Epilepsia. 1989;30(4):389-399.

17 Rocca W, Sharbrough F, Hauser W, et al. Risk factors for complex partial seizures: a population-based case-control study. Ann Neurol. 1987;21(1):22-31.

18 Falconer M, Serafetinides E, Corsellis J. Etiology and pathogenesis of temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Neurol. 1964;10:233-248.

19 Hedera P, Blair MA, Andermann E, et al. Familial mesial temporal lobe epilepsy maps to chromosome 4q13. 2-q21. 3. Neurology. 2007;68(24):2107-2112.

20 Betting LE, Mory SB, Lopes-Cendes I, et al. MRI reveals structural abnormalities in patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Neurology. 2006;67(5):848-852.

21 Treatment of convulsive status epilepticus. Recommendations of the Epilepsy Foundation of America’s Working Group on Status Epilepticus. JAMA. 1993;270(7):854-859.

22 Lowenstein DH, Bleck T, Macdonald RL. It’s time to revise the definition of status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 1999;40(1):120-122.

23 Chang B, Schomer DL. Ambulatory EEG monitoring. In Burgess R, Klem G, Luders H, editors: Fundamentals of EEG technology, ed 2, Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 2005.

24 Marsan CA, Zivin LS. Factors related to the occurrence of typical paroxysmal abnormalities in the EEG records of epileptic patients. Epilepsia. 1970;11(4):361-381.

25 Salinsky M, Kanter R, Dasheiff RM. Effectiveness of multiple EEGs in supporting the diagnosis of epilepsy: an operational curve. Epilepsia. 1987;28(4):331-334.

26 Ellingson RJ, Wilken K, Bennett DR. Efficacy of sleep deprivation as an activation procedure in epilepsy patients. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1984;1(1):83-101.

27 Cendes F, Andermann F, Gloor P, et al. MRI volumetric measurement of amygdala and hippocampus in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 1993;43(4):719-725.

28 Engel JJr, Kuhl DE, Phelps ME, et al. Interictal cerebral glucose metabolism in partial epilepsy and its relation to EEG changes. Ann Neurol. 1982;12(6):510-517.

29 O’Brien TJ, So EL, Mullan BP, et al. Subtraction ictal SPECT co-registered to MRI improves clinical usefulness of SPECT in localizing the surgical seizure focus. Neurology. 1998;50(2):445-454.

30 Knake S, Halgren E, Shiraishi H, et al. The value of multichannel MEG and EEG in the presurgical evaluation of 70 epilepsy patients. Epilepsy Res. 2006;69(1):80-86.

31 Benbadis SR, O’Neill E, Tatum WO, et al. Outcome of prolonged video-EEG monitoring at a typical referral epilepsy center. Epilepsia. 2004;45(9):1150-1153.

32 Lancman ME, Brotherton TA, Asconape JJ, et al. Psychogenic seizures in adults: a longitudinal analysis. Seizure. 1993;2(4):281-286.

33 Fiszman A, Alves-Leon SV, Nunes RG, et al. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a critical review. Epilepsy Behav. 2004;5(6):818-825.

34 Gates JR, Ramani V, Whalen S, et al. Ictal characteristics of pseudoseizures. Arch Neurol. 1985;42(12):1183-1187.

35 Saygi S, Katz A, Marks DA, et al. Frontal lobe partial seizures and psychogenic seizures: comparison of clinical and ictal characteristics. Neurology. 1992;42(7):1274-1277.

36 Reuber M, Pukrop R, Bauer J, et al. Outcome in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: 1 to 10-year follow-up in 164 patients. Ann Neurol. 2003;53(3):305-311.

37 Benbadis S, Agrawal V, Tatum W. How many patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures also have epilepsy? Neurology. 2001;57(5):915-917.

38 McKeon A, Vaughan C, Delanty N. Seizure versus syncope. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(2):171-180.

39 Lempert T, Bauer M, Schmidt D. Syncope: a videometric analysis of 56 episodes of transient cerebral hypoxia. Ann Neurol. 1994;36(2):233-237.

40 Lin JT, Ziegler DK, Lai CW, et al. Convulsive syncope in blood donors. Ann Neurol. 1982;11(5):525-528.

41 Milligan TA, Bromfield E. A case of “migralepsy,”. Epilepsia. 2005;46(suppl 10):2-6.

42 Liporace J, Sperling M. Simple autonomic seizures. In: Engel J, Pedley T, editors. Epilepsy: a comprehensive textbook. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1998.

43 French JA, Kanner AM, Bautista J, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of the new antiepileptic drugs I: treatment of new onset epilepsy: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee and Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2004;62(8):1252-1260.

44 Marson AG, Al-Kharusi AM, Alwaidh M, et al. The SANAD study of effectiveness of carbamazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, or topiramate for treatment of partial epilepsy: an unblinded randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9566):1000-1015.

45 Marson AG, Al-Kharusi AM, Alwaidh M, et al. The SANAD study of effectiveness of valproate, lamotrigine, or topiramate for generalised and unclassifiable epilepsy: an unblinded randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9566):1016-1026.

46 Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Early identification of refractory epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(5):314-319.

47 Arif H, Buchsbaum R, Weintraub D, et al. Comparison and predictors of rash associated with 15 antiepileptic drugs. Neurology. 2007;68(20):1701-1709.

48 Engel JJr, Wiebe S, French J, et al. Practice parameter: temporal lobe and localized neocortical resections for epilepsy: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology, in association with the American Epilepsy Society and the American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Neurology. 2003;60(4):538-547.

49 Wiebe S, Blume WT, Girvin JP, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of surgery for temporal-lobe epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(5):311-318.

50 Stroup E, Langfitt J, Berg M, et al. Predicting verbal memory decline following anterior temporal lobectomy (ATL). Neurology. 2003;60(8):1266-1273.

51 Kuzniecky R, Garcia J, Faught E, et al. Cortical dysplasia in temporal lobe epilepsy: magnetic resonance imaging correlations. Ann Neurol. 1991;29(3):293-298.

52 Palmini A, Andermann F, Olivier A, et al. Focal neuronal migration disorders and intractable partial epilepsy: a study of 30 patients. Ann Neurol. 1991;30(6):741-749.

53 Lanska DJ. J. L. Corning and vagal nerve stimulation for seizures in the 1880s. Neurology. 2002;58(3):452-459.

54 A randomized controlled trial of chronic vagus nerve stimulation for treatment of medically intractable seizures. The Vagus Nerve Stimulation Study Group. Neurology. 1995;45(2):224-230.

55 Ardesch JJ, Buschman HP, Wagener-Schimmel LJ, et al: Vagus nerve stimulation for medically refractory epilepsy: a long-term follow-up study, Seizure, 2007 (electronic prepublication).

56 Salinsky MC, Uthman BM, Ristanovic RK, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of medically intractable seizures. Results of a 1-year open-extension trial. Vagus Nerve Stimulation Study Group. Arch Neurol. 1996;53(11):1176-1180.

57 Rush AJ, George MS, Sackeim HA, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for treatment-resistant depressions: a multicenter study. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47(4):276-286.

58 Gaitatzis A, Trimble MR, Sander JW. The psychiatric comorbidity of epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2004;110(4):207-220.

59 Harden CL, Goldstein MA. Mood disorders in patients with epilepsy: epidemiology and management. CNS Drugs. 2002;16(5):291-302.

60 Lambert M, Robertson M. Depression in epilepsy: etiology, phenomenology, and treatment. Epilepsia. 1999;40(suppl 10):S21-S47.

61 Ring HA, Moriarty J, Trimble MR. A prospective study of the early postsurgical psychiatric associations of epilepsy surgery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;64(5):601-604.

62 Hesdorffer DC, Hauser WA, Annegers JF, et al. Major depression is a risk factor for seizures in older adults. Ann Neurol. 2000;47(2):246-249.

63 Hitiris N, Mohanraj R, Norrie J, et al. Predictors of pharmacoresistant epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2007;75(2-3):192-196.

64 Kanner AM, Balabanov A. Depression and epilepsy: how closely related are they? Neurology. 2002;58(8 suppl 5):S27-S39.

65 Yilmaz I, Sezer Z, Kayir H, et al: Mirtazapine does not affect pentylenetetrazole- and maximal electroconvulsive shock-induced seizures in mice, Epilepsy Behav, 2007 (electronic prepublication).

66 Barry J, Lembke A, Hyunh N. Affective disorders in epilepsy. In: Ettinger E, Kanner A, editors. Psychiatric issues in epilepsy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001.

67 Swinkels WA, Kuyk J, van Dyck R, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;7(1):37-50.

68 Landolt H. Serial electroencephalographic investigations during psychotic episodes in epileptic patients and during schizophrenic attacks. In: de Haas L, editor. Lectures on epilepsy. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1958.

69 McConnell H, Duncan D. Treatment of psychiatric comorbidity in epilepsy. In: McConnell H, Synder P, editors. Psychiatric comorbidity in epilepsy. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1998.

70 Reutens DC, Savard G, Andermann F, et al. Results of surgical treatment in temporal lobe epilepsy with chronic psychosis. Brain. 1997;120(pt 11):1929-1936.

71 Manchanda R, Schaefer B, McLachlan RS, et al. Psychiatric disorders in candidates for surgery for epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;61(1):82-89.

72 Scicutella A. Anxiety disorders in epilepsy. In: Ettinger A, Kanner A, editors. Psychiatric issues in epilepsy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001.

73 Parmar H, Lim SH, Tan NC, et al. Acute symptomatic seizures and hippocampus damage: DWI and MRS findings. Neurology. 2006;66(11):1732-1735.

74 Holmes GL, Lenck-Santini PP. Role of interictal epileptiform abnormalities in cognitive impairment. Epilepsy Behav. 2006;8(3):504-515.

75 Waxman SG, Geschwind N. The interictal behavior syndrome of temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32(12):1580-1586.

76 Schachter SC. Epilepsy: quality of life and cost of care. Epilepsy Behav. 2000;1(2):120-127.

77 Devinsky O, Vickrey BG, Cramer J, et al. Development of the quality of life in epilepsy inventory. Epilepsia. 1995;36(11):1089-1094.