CHAPTER 68 Managed Care and Psychiatry

OVERVIEW

—Noted economist Ariel Rubinstein, upon the awarding of the Nobel Prize to the economist John Nash in 19941

THE HISTORY OF MENTAL HEALTH CARE FINANCE IN THE UNITED STATES

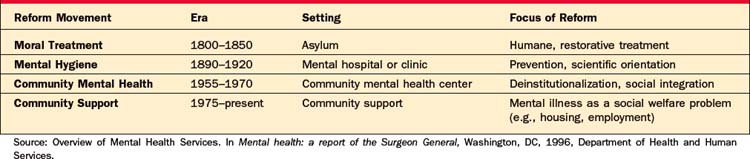

Throughout the history of the United States, social movements relating to the care of the mentally ill have altered the delivery and financing of MHC3 (Table 68-1). After the Revolutionary War, increasing urbanization led to the development of asylums for the mentally ill, most notably in Philadelphia (Pennsylvania) and Williamsburg (Virginia). Before the establishment of these state-run, state-financed psychiatric hospitals, local communities and families bore the brunt of the responsibility for caring for the mentally ill, initially through local almshouses (poorhouses) and then through more formalized financing methods. As the financial burden on localities increased over time, an effort was made to shift the costs of financing MHC to the states. A corollary goal supported by the psychiatric profession involved separating the financing of care for the mentally ill from local, charity-based indigent care.

A group of reformers (led by Horace Mann, among others) led the “moral treatment” movement, which advocated for the institutionalization of patients with the hopes that early treatment would lead to a resolution of their mental illness. The activist Dorthea Dix, in particular, was instrumental in lobbying state legislatures for the establishment of psychiatric hospitals. Eventually, each state developed its own asylum system in response to the movement. Over the course of the nineteenth century, asylums became overcrowded, and, as the promise of early intervention went largely unfulfilled, asylums became the permanent home to many chronically ill patients. Funding of asylums did not increase with the rise in the patient population. State and local governments were in conflict as to how to fund mental health services, with the latter often choosing to place the mentally ill in jail or in almshouses rather than pay for care at asylums.4 In the latter half of the nineteenth century, a new movement known as the “mental hygiene” movement sought to improve the conditions of patients in asylums. A number of federal laws, known as the State Care Acts, required states to pay for all asylum care, prompting localities to send an ever-increasing number of patients to asylums. Reformers from the National Committee on Mental Hygiene also advocated for treatment of mental illness in medical hospitals, as well as in outpatient settings, bringing MHC more into the medical model of care. This continued to be the case into the 1930s when a new method of private employer–based health insurance financing was born.5

THE RISE OF PRIVATE HEALTH INSURANCE

The current system of employer-based health insurance, while accidental in its conception, has become entrenched as the primary way by which health care is financed in this country. Until the 1930s, private individuals paid out-of-pocket for health care services on a fee-for-service basis.6 During the 1930s, nonprofit Blue Cross/Blue Shield (BCBS) health insurance plans were developed and, despite skepticism as to their viability, were successful. Once health insurance was shown by the BCBS plans to be a financially feasible endeavor, a number of private for-profit health insurance companies were founded. During World War II, when the government allowed employers to offer health insurance in lieu of wage increases, private health insurers grew in both size and number, with the number of covered individuals rising from 20.6 million to 142 million between 1940 and 1950.6 Coverage expanded even further and became more tightly linked to employment contracts when, in 1954, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) ruled that employer-based health insurance should not be considered as taxable income. While coverage was expanded for general medical care, MHC coverage was substantially more limited. Insurance policies did not include mental health services until after World War II, when insurers began covering some hospital-based psychiatric care. Before the deinstitutionalization movement (discussed in the next section), there was little incentive for private insurers to cover services that were already paid for through the public sector.7

THE COMMUNITY MENTAL HEALTH CENTER MOVEMENT AND DEINSTITUTIONALIZATION

In the 1950s, a third movement in United States MHC began, referred to as the Community Mental Health Center Movement. It was founded on the belief that, with the advent of new and improved pharmacological and somatic treatments, MHC was best delivered in the community. Movement advocates pointed to continued poor conditions in asylums as evidence that deinstitutionalization of patients would best serve their interests.5 Federal legislation in the early 1960s targeted federal funds for the development of community mental health centers (CMHCs) across the country. According to historian Gerald Grob, the deinstitutionalization of patients was not simply an en masse exodus from mental hospitals to the community, but rather a shift in emphasis from long-term care to management of more acute episodes, driven by the expansion of outpatient services through CMHCs.5

During this time, funding for MHC services became more complex. Services (such as medical care housing and meals that were at one time contained in mental hospitals) were no longer provided within a single context. Federal programs (such as the Social Security Disability Insurance [SSDI] program) would become increasingly important for providing financial support to the chronically mentally ill. Additionally, new public health insurance programs in the 1960s would further change the way MHC was financed.

INSURING MENTAL HEALTH CARE: MORAL HAZARD, ADVERSE SELECTION, AND THE RISE OF MANAGED BEHAVIORAL CARVE-OUTS

With the provision of MHC increasingly financed by public and private insurance plans over the latter half of the twentieth century, economic problems inherent in the structure of the health care market became increasingly evident. From the mid-1960s until the early 1990s, health costs increased by an annual rate of 4.1%8 compared with a 1.5% increase in the gross domestic product (GDP). Such a rise was believed to be largely due to both a rise in technological advances, such as new drugs and devices and a health insurance market that was ineffective and inefficient at rationing care (with the latter allowing ever-increasing usage and total costs brought on in part by the former). In order to understand the rise of managed care plans and their impact on mental health, it is crucial to understand the “basic science” of health insurance that leads to difficulties with financing care.

The main problem in financing medical care (both in the private and public sector) relates to the fact that the buyer-seller relationship is more complicated than with traditional goods.9 In a normal marketplace for a good or a service, a seller offers a product at a given price, and a buyer determines whether or not to buy the product. In health care, the seller (physician) usually determines whether or not the consumer (patient) should receive care while a third party (insurers) decides whether care will be paid for. Since patients, physicians, and insurers all have different incentives that often conflict, the market can become quite complicated and inefficient.

More specifically, two economic concepts have shaped the development of United States health insurance. Both are related to what economists term information asymmetries, where the insured are known to have more complete information about their health than their insurers do. The first concept is referred to as moral hazard.10 It states that individuals who obtain a product or service at no cost will consume more of it than if they paid a price for it. Much as the person who overeats at an all-you-can-eat buffet, this behavior affects the use of health care services (i.e., without any cost to themselves for health care services, individuals will use more than may be appropriate or necessary). The RAND health experiment in the 1970s showed that when individuals had copays for care, their utilization of medical services decreased without a decrease in health outcome.11 An example of how concerns over moral hazard have affected mental health financing relates to the coverage of psychotherapy. As psychotherapy is a relatively discretionary treatment on the part of providers and patients with few objectively measured end-points, full coverage of such treatment has been thought to cause over-utilization in the absence of shared costs by the patient.12 This idea of patients sharing costs as a way of controlling moral hazard–induced overuse was tested in the 1970s by the RAND health insurance experiment. Evidence from the RAND study showed that individuals tended to decrease their use of psychotherapy services at roughly double the rate of other medical services when faced with copayments; this suggested that the relative value of additional psychotherapy sessions was less than that of health-related services.11,13

The second concept that has shaped the development of our current health care system is known as adverse selection.14 Adverse selection occurs because individuals are usually more aware of their health status than are insurers. If an individual thinks that he is buying more insurance than he needs given his good health, he will choose to move to plans with lower benefits at a lower cost. As more healthy people leave a given plan, the average cost of insuring the (less healthy) people remaining in that plan becomes higher, thus making insurance premiums more expensive, causing yet more people to leave, eventually leading to a less than optimal market.

Adverse selection–related incentives are particularly strong in MHC. Numerous studies have shown that insurance plans with slightly better benefits have significantly higher utilization of MHC services, implying that people with mental illness seek out plans with better benefits.2 Evidence indicates that those with prior mental health service use are likely to have higher health spending in future years15 and tend to use other medical services at higher rates compared to otherwise similar individuals.15 Given that insurance companies lose money on such “high-utilizers” who cost more per person than they pay into a plan, a strong incentive exists to offer plans that have limited mental health benefits to discourage this particular group of high-utilizers from joining their plans.

MANAGED CARE AND THE RISE OF “CARVE-OUT” PLANS

The idea of rationing medical care through prepaid health insurance plans that would “manage care” of patients had been in existence since the nineteenth century.16 Such plans were usually through a group of physicians that would contract for the health care needs of groups of individuals, either in an industry or a locale. The rise of the Kaiser-Permanente health system in post–World War II California created the largest managed care organization; it enrolled half a million people within 10 years.

The idea of managed care received a big boost in the early 1970s when the Nixon administration, in response to repeated calls for health care reform due in large part to rising costs, passed legislation that supported the expansion of managed care.17 The term health maintenance organization (HMO) was coined to describe the plans that, while using different strategies, all offered specified plan services for a fixed premium. With the passage of the Managed Care Act of 1973, HMOs rose from 30 in 1970 to over 1,700 in 1976, eventually covering 90% of privately insured individuals in the this country.

While HMOs continued to grow in number and size, the coverage of MHC continued to lag behind other medical services. As mentioned in the previous section, insurers were reluctant to cover services that were already paid for by the government due to concerns about adverse selection. This aversion to covering MHC benefits was supported by the federal government’s experience with covering MHC benefits for its employees. In the early 1960s the Kennedy administration directed the United States civil service agency to begin offering mental health benefits at an equivalent level as general medical care in two nationally available Federal Employee Health Benefits (FEHB) Program health plans.18 Beginning in 1975, federal employee health plans were permitted to scale back their mental health benefits due to significant losses by those plans from MHC benefit coverage.19 By the late 1970s, the Blue Cross/Blue Shield high-option plan remained the only health plan that provided generous psychiatric coverage and was severely selected against for a number of years until it was permitted to make significant cuts in benefits in 1981. This episode prompted the general perception among policymakers and insurers that broad coverage for mental health was expensive and unpredictable due to issues relating to moral hazard and adverse selection.

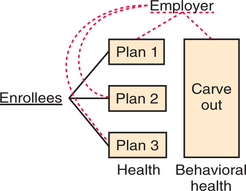

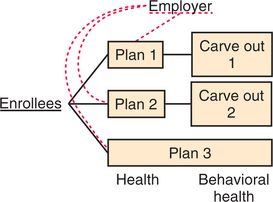

Managed care has continued to transform MHC financing over the last decade. With the evolution of managed care, business entities often referred to as “carve-outs” have emerged to manage the delivery of MHC. Both employers and health plans increasingly contracted with care carve-out firms to manage their mental health benefits. According to a 2002 survey, about 164 million individuals with health coverage were enrolled in some type of managed behavioral health program in 2002, totaling 66% of individuals with health insurance.20 The survey data indicate a substantial increase over the decade in enrollment in carve-outs from 70 million in 1993 to 164 million in 2002. Employers and health plans structure carve-out contracts in various ways. For example, a carve-out contract with an employer might be a risk-based or a non–risk-based contract (administrative services only); it might provide utilization review or case management services only; it might provide employee assistance program (EAP) services only; or it might contract to provide both managed behavioral health services and EAP services. Larger carve-out firms may market all of these separate services depending on the needs of a given purchaser. Figures 68-1 and 68-2 illustrate some of the more common carve-out formats.

Carve-out contracts have been touted as a strategy for improving the cost-effectiveness of behavioral health care. These firms use specialized expertise to assemble networks of mental health specialty providers willing to accept lower reimbursement rates, to identify evidence-based treatment protocols, and to use other managed care techniques (e.g., care management and utilization review) with the promise of reducing employer expenditures without sacrificing access to needed services. Observational studies of contracting with carve-outs have consistently produced evidence of substantial reductions in mental health and substance abuse costs even in the context of benefit expansion in both the private sector21–23 and the public sector.21,24–27 These studies have shown that most savings result from decreases in use and spending for inpatient care. Most often, the proportion of enrollees using outpatient care increased while the number of outpatient visits decreased with adoption of carve-outs. The evidence on how carve-outs affect quality of care is more ambiguous. To date, fewer studies have examined the effects of carve-outs on quality. Carve-outs do not appear to increase rates of rehospitalization.28,29 However, studies have produced mixed results on their effects on continuity of care,28,30 adherence to treatment guidelines,31,32 and clinical outcomes.33

A second rationale for contracting with carve-outs relates to employer concerns regarding the consequences of adverse selection. By “carving out” mental health benefits to a single specialty carve-out firm, an employer can eliminate the incentive among health plans to compete in avoiding enrollment of more expensive individuals with a need for mental health services. Under this arrangement, enrollees may be given a choice of health plan but are not given a choice of plan for the carved-out mental health services (see Figure 68-1). In this case, introduction of an employer-level carve-out can attenuate selection incentives. However, carving out will not have any impact on selection when contracting occurs at the health plan level. In this case, carve-outs are a component of a health plan’s business strategy and do not affect the plan’s incentives to avoid enrolling individuals with mental illness.

A common criticism of carve-outs is that these institutional arrangements fragment care in an already poorly integrated MHC delivery system. Common problems include challenges in coordinating care for patients with multiple conditions and the inability of primary care physicians to bill for providing mental health treatment when carve-outs are under contract to provide specialty mental health care services. Separate carve-out vendors and prescription drug budgets contribute to and reinforce tendencies to avoid using integrated approaches to treat patients with mental health conditions. Fragmentation may also create opportunities to shift costs. For example, carve-outs are often accused of encouraging greater use of pharmaceutical treatments that are treated as “off-budget” from a contractual standpoint. Another criticism of carve-outs is that these arrangements increase administrative costs. Estimates of increases in administrative costs due to these arrangements range from 8% to 20% of mental health benefit costs.2

RECENT TRENDS IN MENTAL HEALTH CARE FINANCING

Gross Spending on Mental Health Care

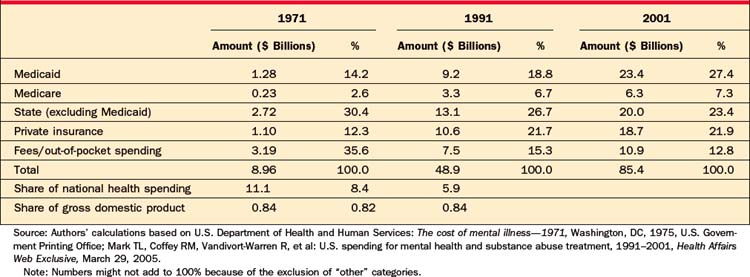

Total domestic spending on MHC in the United States in 2001 was $85.4 billion.34 MHC expenditures were estimated at 5.9% of total spending on health care and 0.84% of the GDP. Frank and Glied35 compared estimates of health care spending with those from 1971, controlling for changes in treatment over that period. They found that in 1971 total expenditures on MHC were $8.96 billion, 11.1% of the total spending on health and nearly twice as much as in 2001. MHC spending was still 0.84% of the GDP at that time.35

While total spending on MHC has stayed constant in terms of the GDP, relative spending on different treatment modalities has changed dramatically. Following on the heels of the CMHC movement and changes in financing, the number of institutionalized patients decreased from 433,000 people in 1971 to 170,000 in 2000. This shift in care affected financing of MHC, and the burden shifted from state governments to insurance-based mechanisms, both public and private. While the numbers of institutionalized patients fell, there was a sharp increase in MHC provided to noninstitutionalized patients. The number of United States citizens receiving MHC has increased by 50% since 1977. Total spending on noninstitutionalized patients has also increased.35

It is also important to note that many of the costs associated with long-term care of the chronically mental ill (such as housing and board) were transferred to other programs considered outside the realm of MHC. The expansion of public insurance programs such as Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), public housing, and food stamps in the 1970s helped cover the cost of community-based living for patients.

Sources of Health Care Expenditures

Almost 50% of MHC-related expenses in the United States in 2001 were paid for by public funding sources. Table 68-2 and Figure 68-2 describe and exhibit some of the major public funders of MHC (including Medicare, Medicaid, and non-Medicaid state spending programs). As shown in Table 68-2, federal sources of funding (Medicaid and Medicare) increased from 16.8% of total MHC spending in 1971 to over 34% in 2001, while state spending decreased from 30.4% in 1971 to 23.4% in 2001.34

PARITY AND THE FUTURE OF MENTAL HEALTH CARE IN THE UNITED STATES

Insurance parity has been the stated objective of mental health advocates since differences in mental and general health coverage first arose in the early days of private health insurance.36 Parity policies require health plans operating in the private health insurance market to provide an equivalent level of coverage for mental health and general health care. The case for parity has primarily been based on the fairness argument that insurance should not discriminate against those with mental illness.

Some health insurers and employers remain opposed to improving mental health insurance coverage due to concern about costs. Early research evidence from the 1970s and 1980s (before the introduction of managed care) supported employers’ concerns that covering outpatient mental health parity would “break the bank.”37 Early studies sought to understand whether and to what extent demand for outpatient MHC (with a focus on psychotherapy) differed from general medical care. A recent review article summarized the studies on demand response to cost-sharing provisions for outpatient mental health services published between 1981 and 1989. It noted that these studies supported the conclusion that higher cost-sharing for psychotherapy was justified. These early studies contrasted with a second generation of research conducted beginning in the late 1990s on mental health benefit expansions in the era of managed care. The second-generation studies did not find large mental health spending increases attributable to parity, and all studies that addressed risk-protection identified significant decreases in consumer out-of-pocket MHC spending under managed care. The absence of quantity increases due to parity across these studies is consistent with more recent actuarial estimates of the effect of parity on premiums.

These more recent studies provide evidence that parity implemented in the context of managed care would have little impact on mental health spending and would increase risk protection for those with mental health conditions. It is worth noting that comprehensive parity is not a panacea for all of the problems in MHC financing and delivery. Most notably, expanding benefits under parity may help but does not solve the problem of unmet need or ensure use of evidence-based medicine in MHC. As such, parity has often been described as a necessary but insufficient policy for advancing equitable, high-quality, and nondiscriminatory health insurance coverage for persons with mental health disorders.38

1 Nasar S. The lost years of a Nobel Laureate. New York Times. November 13, 1994.

2 Frank RG, McGuire T. Economics and mental health. In: Cuyler AJ, Newhouse JP, editors. Handbook of health economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2000.

3 Overview of Mental Health Services. In Mental health: a report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 1996.

4 Grob GN. Mental illness and American society, 1875-1940. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983.

5 Grob GN. The mad among us: a history of the care of America’s mentally ill. New York: Free Press, 1994.

6 Blumenthal D. Employer-sponsored health insurance in the United States—origins and implications. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(1):82-88.

7 Frank RG, Koyanagi C, McGuire T. The politics and economics of mental health parity laws. Health Affairs. 1997;16(4):108-120.

8 Chernew ME, Hirth RA, Cutler DM. Increased spending on health care: how much can the United States afford? Health Affairs. 2005;22(4):15-25.

9 Arrow KJ. Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care. Am Economic Review. 1963;53(5):941-973.

10 Pauly MV. The economics of moral hazard: comment. Am Economic Review. 1968;58(3 pt 1):531-537.

11 Manning WG, Wells K, Buchanan J, et al. Effects of mental health insurance: evidence from the Health Insurance Experiment. Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 1989.

12 McGuire TG. Financing and demand for mental health services. J Hum Resour. 1981;16(4):501-522.

13 Newhouse JP. Free for all? Lessons from the RAND Health Insurance Experiment. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993.

14 Sitglitz J, Rothschild M. Equilibrium in competitive insurance markets: an essay on the economics of imperfect information. Q J Economics. 1976;90(4):629-649.

15 Frank RG, Glazer J, McGuire TG. Adverse selection in mental health care. J Health Economics. 2000;19(6):829-854.

16 Tufts Managed Care Institute. A brief history of managed care, 1998. Available at www.thci.org/downloads/BriefHist.pdf.

17 Fox D. An overview of managed care. In Kongstvedt P, editor: The managed health care handbook, ed 3, Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen, 1996.

18 Hustead E, Sharfstein SS, Muszinski S, et al. Reductions in coverage for mental and nervous illness in the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program 1980-1984. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:181-186.

19 Hustead EC, Sharfstein SS. Utilization and cost of mental illness coverage in the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program. Am J Psychiatry. 1978;135:315-319.

20 Oss ME, Jardine EL, Pesare MJX. Open Minds yearbook of managed behavioral health and employee assistance program market share in the U.S. 2002-2003. Gettysburg, PA: Open Minds, 2004.

21 Burns BJ, Teagle SE, Schwartz M, et al. Managed behavioral health care: a Medicaid carve-out for youth. Health Affairs. 1999;18(5):214-225.

22 Ma CA, McGuire TG. Costs and incentives in a behavioral health care carve out. Health Affairs. 1998;17(2):53-69.

23 Grazier KL, Eselius LL, Hu TW, et al. Effects of a mental health carve-out on use, costs and payers: a four-year study. J Behav Health Serv Res. 1999;26(4):381-389.

24 Bloom JR, Hu TW, Wallace N, et al. Mental health costs and access under alternative capitation systems in Colorado. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(2):315-340.

25 Christianson JB, Manning W, Lurie N, et al. Utah’s Prepaid Mental Health Plan: the first year. Health Affairs. 1995;14(3):160-172.

26 Huskamp HA. Episodes of mental health and substance abuse treatment under a managed behavioral health care carve-out. Inquiry. 1999;36(2):147-161.

27 Frank RG, McGuire TG. Savings from a Medicaid carve-out for mental health and substance abuse care. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48(9):1147-1152.

28 Merrick E. Treatment of major depression before and after implementation of a behavioral health carve-out plan. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(11):1563-1567.

29 Sturm R. Tracking changes in behavioral health services: how have carve-outs changed care? J Behav Health Serv Res. 1999;26(4):360-371.

30 Dickey B, Norton EC, Normand SL, et al. Managed mental health experience in Massachusetts. New Dir Ment Health Serv. 1998;78:115-122.

31 Busch AB, Frank RG, Lehman AF. The effect of a managed behavioral health care carve-out on quality of care for Medicaid patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:442-448.

32 Busch SH. Specialty health care, treatment patterns and quality: a case study of treatment for depression. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(6):1583-1601.

33 Cuffel BJ, Bloom JR, Wallace N, et al. Two-year outcomes of fee-for-service and capitated medicaid programs for people with severe mental illness. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(2):341-359.

34 Mark TL, Coffey RM, Vandivort-Warren R, et al: U.S. spending for mental health and substance abuse treatment, 1991-2001, Health Affairs Web Exclusive, March 29, 2005.

35 Frank R, Glied S. Changes in mental health financing since 1971: implications for policymakers and patients. Health Affairs. 2006;25(3):601-613.

36 Reed L, Myers E, Scheidemandel P. Health insurance and psychiatric care: utilization and cost. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1972.

37 Barry CL, Frank RG, McGuire TG. The costs of mental health parity: still an impediment? Health Affairs. 2006;25(3):623-634.

38 Hennessy KD, Goldman H. Full parity: steps toward treatment equity for mental and addictive disorders. Health Affairs. 2001;20(4):58-67.