CHAPTER 64 Chronic Mental Illness

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND MANIFESTATIONS

The prevalence of schizophrenia is 1%; the condition affects equal numbers of men and women. However, the rates vary by region, with higher rates among the urban poor (probably because of the movement of these patients toward urban areas where treatment is more available than it is in rural settings). The course of schizophrenia is variable; about 10% of patients who are diagnosed with schizophrenia become completely asymptomatic, about 20% remain severely disabled, and the remainder will have a fluctuating course.1 Maintenance of antipsychotic medications after the first episode of illness appears to decrease rates of relapse.2 Among patients with schizophrenia, about 10% commit suicide and 50% attempt it.3

Direct and indirect costs of schizophrenia in the United States have been estimated at more than $62 billion in 2002, with over $22 billion accounting for direct health care.4 Examples of non–health care costs include living expenses, lost productivity due to unemployment or early death from suicide, the cost for families to provide care, and costs for law enforcement and homeless shelters.

An individual’s ability to function depends on how symptoms impinge on his or her life. For example, auditory hallucinations, delusions, and paranoia may interfere with work and relationships as the patient incorporates co-workers or significant others into the delusional beliefs. Disorganized thought, language, and behavior may impair the patient’s ability to live independently, to participate in employment and social situations, or to access medical and psychiatric care on his or her own. Among some patients, agitation is a component of the disorganization that could potentially lead to dangerous situations for the patient or caregivers. Finally, negative symptoms of schizophrenia (including apathy, flattening of affect, poverty of thought and speech, social isolation, and neglect of hygiene) can also interfere with a patient’s ability to participate in daily activities and can alienate those around him or her.3

THE STIGMA OF CHRONIC MENTAL ILLNESS

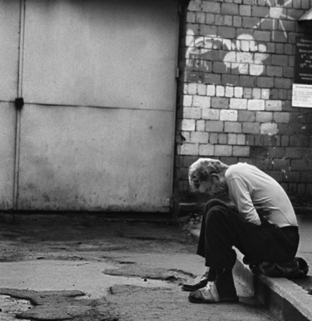

The individual who suffers from a chronic mental illness, such as schizophrenia, not only has to cope with the symptomatic aspects of his or her illness, but also suffers from the additional burden of being stigmatized by those around him or her (Figure 64-1). Goffman5 has defined stigma as “an attitude that is deeply discrediting” and describes that the stigma of mental illness is based on the belief that suffering from mental illness represents “a blemish on individual character.” Norman Sartorius,6 the former director of the Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse at the World Health Organization, and others have focused on stigma as the major obstacle world-wide to quality care and to improved quality of life for those with mental illness. Stigma leads to discrimination of individuals with mental illness; they become viewed as second-class citizens who are different, separate, or ostracized from society. Discrimination is manifest in many ways, including outright poor treatment by others, avoidance of care by those with mental illness (and their families), and a comparative lack of resources allocated to research and to clinical programs. Some attempts to mitigate the negative effects of stigma (such as educational programs) have been made, but stigma still remains a central issue for those with chronic mental illness.

THE COMMUNITY MENTAL HEALTH CARE SYSTEM

The way that our society views chronic mental illness and supports its treatment has changed dramatically in the United States over the past 200 years. The earliest public mental hospitals were built in the late 1700s as locations to house and care for the mentally ill.7 By 1903, 144,000 people were housed in public mental hospitals in the United States, and by 1955, this number had grown to 559,000.8

However, it was in the 1950s when newly created antipsychotic medications led to significant changes in psychiatric treatment that care could more easily be provided to chronically mentally ill patients in the community. New commitment laws and legal proceedings that restricted involuntary commitment and that endorsed patients’ rights to access care in the least restrictive setting led to more dramatic changes in hospitalization practices.9 In addition, there was a growing belief that treatment in the community would be more humane, and that hospitalization may actually contribute to the withdrawal and apathy associated with chronic mental illness.3,8 All of these factors contributed to a period of deinstitutionalization in which thousands of patients were released from mental hospitals in order to live and receive treatment in the community. In 1998, there were just over 57,000 people in psychiatric hospitals in the United States, a decrease of nearly 90% as compared to 1955.8

In the context of these changes, the federal Community Mental Health Centers Act of 1964 contributed to widespread changes in the availability of resources. Additional financial resources for patients included Supplementary Security Income (SSI), Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), and Medicare and Medicaid health insurance programs. One novel community program already in place before this period of deinstitutionalization was led by Erich Lindemann, and was based on a theory of broad community intervention to understand life crises, with the identification of families at risk, and the strengthening of community resources using a range of professionals (e.g., doctors, clergymen, and educators) to prevent morbidity and to promote healthier coping strategies.10 Lindemann played an important role in the creation of the community mental health system in Boston and encouraged a public health approach to illness prevention, in addition to the treatment available at the community mental health centers. However, some critics have argued that deinstitutionalization was not accompanied by adequate financial and community resources to provide the additional care that patients needed once they left the hospital environment.

One unfortunate effect of inadequate housing and access to treatment has been high rates of homelessness among the chronically mentally ill.8 Homeless adults have about 30 times the prevalence of schizophrenia or mania compared to matched housed samples; about one-fourth of the homeless population report a history of psychiatric hospitalization.11 In addition, the prevalence of schizophrenia is three times higher in jails than it is in the general population.12 These psychiatrically ill patients become institutionalized through the criminal justice system,13 which does not provide the best opportunity or environment for treatment. Some studies have demonstrated slightly increased rates of violence among patients with schizophrenia as compared to those in the general population.14,15 The increased risk of violence is thought to be related to delusional symptoms (e.g., paranoid beliefs that lead a patient to feel the need for retaliation against a person or group responsible for his or her symptoms) and substance abuse, but this has been debated, largely due to the stigmatizing effects of these data. There is some evidence that clozapine treatment may be associated with lower rates of violence and fewer arrests among patients with schizophrenia16,17; this finding warrants further study. Finally, there is evidence to suggest that patients with chronic mental illness suffer from significant medical co-morbidities and that their symptoms may limit them from gaining access to the appropriate medical care in the community.

MEDICAL CO-MORBIDITY

Compelling evidence reveals that individuals with chronic mental illness have higher rates of medical morbidity and mortality when compared with those in the general population. Patients with schizophrenia have a life expectancy of 57 years for men and 65 years for women, which is nearly 20% shorter than the life expectancy of people without mental illness.18 The Massachusetts Department of Mental Health review of client deaths in 2000 revealed a mortality rate for patients with severe mental illness that was three times higher than it was in the age-matched comparison group.19 Cardiovascular disease was the most significant contributor to the increase in deaths, followed by respiratory illnesses. The difference in mortality rate between the two populations was most notable for individuals in the 25- to 44-year-old age-group. In this age-group, cardiac deaths were more than sixfold higher than were age-matched comparison samples.19,20

Review of baseline data from the recent Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study also confirmed that patients with schizophrenia have a high prevalence of the metabolic syndrome,21,22 which is a known risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Factors such as poor diet, a sedentary lifestyle, and lower rates of compliance with medication may also play a role in the elevated rates of physical morbidity and mortality in the chronic mentally ill population.

Weight Gain and Obesity

Obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or greater, is a serious health concern associated with an increased risk for many diseases, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus [DM], dyslipidemia, stroke, and cardiovascular disease. Although the prevalence of obesity in the United States has increased dramatically over the past 20 years, individuals with severe mental illness are even more likely than those in the general population to be overweight or obese.23,24

Obesity also has important effects on patients’ self-image and regular use of prescribed medications.25 Weight gain is a significant side effect of medication that may reduce a patient’s adherence or lead to treatment discontinuation.26 Among the atypical antipsychotic medications, clozapine and olanzapine are associated with the most clinically significant weight gain, quetiapine and risperidone convey a moderate risk, and aripiprazole and ziprasidone are least likely to cause weight gain.27–30 Certain mood stabilizers and antidepressants (notably, amitriptyline, mirtazapine, paroxetine, valproic acid, and lithium) are also associated with weight gain.31

Diabetes Mellitus

Patients with chronic mental illness are at higher risk for developing type 2 diabetes than are those in the general population.32 A recent New York State study33 found that the prevalence of DM was 14.2% (between 2001 and 2002) among a cohort of 436 outpatients with schizophrenia. This is nearly double the prevalence (of 7.7%) among the general New York State population during the same period. Accumulating data link treatment with atypical antipsychotic drugs to an increased incidence of DM. Clozapine and olanzapine have the highest association, followed by quetiapine and risperidone.34–37 Weight gain does not appear to be necessary for development of type 2 DM in this population; studies show that clozapine and olanzapine induce an insulin resistance that occurs even in the absence of obesity or weight gain.37,38

Smoking

The prevalence of cigarette smoking is estimated to be as high as 85% in patients with schizophrenia and 60% to 70% in patients with bipolar disorder as compared to a rate of 23% in the general population.39,40 Patients with schizophrenia are also more likely to be classified as heavy smokers (defined as more than 25 cigarettes per day).41 One theory is that the high prevalence of smoking among patients with schizophrenia is due to self-medication with nicotine as a way to address the deficits in attention and cognition that are present in schizophrenia, since nicotine has been shown to improve sustained attention, memory, and information processing.42,43 Smoking may also decrease extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) (e.g., akathisia, dystonia, and parkinsonian symptoms) associated with use of antipsychotic medications, by decreasing medication serum levels via induction of hepatic metabolism. Another theory is that patients with schizophrenia may smoke heavily to overcome the marked dopamine receptor blockade that occurs with antipsychotic medications to help produce reward effects.41

Major obstacles to smoking cessation in this population include a sensitivity to nicotine withdrawal symptoms (e.g., anxiety, irritability, and decreased concentration and sleep), limited social support to encourage quitting, and being surrounded by others who smoke. Patients may also use smoking to cope with stress, anxiety, and depression. The most effective strategy for smoking cessation involves a combination of supportive, behavioral, and pharmacological therapy (including bupropion and nicotine replacement).44 It is important to keep in mind that smoking alters the metabolism of many medications through induction of the CYP 1A2 isoenzyme system. When patients cut back or stop smoking completely, certain medication levels (e.g., clozapine) should be closely monitored and doses lowered accordingly.

Infectious Disease

Patients with chronic mental illness are also at higher risk for contracting infectious diseases (including hepatitis B and C, tuberculosis, and human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection). Studies of mentally ill outpatients have found an HIV seropositivity rate of 3%, which is nearly eight times the overall rate in the United States population. Rates of hepatitis B and C were elevated fivefold and elevenfold, respectively.45,46 Risk factors among this population include a high incidence of drug use, impulsivity, high-risk sexual activity, homelessness, and poor knowledge about HIV transmission.

Side Effects of Medications

Patients with chronic mental illness frequently suffer from side effects of various medications, and those side effects must be balanced with the benefits of an increased ability to function and to participate in ADLs.47 Side effects of neuroleptics include sedation, anticholinergic symptoms (e.g., dry mouth and constipation), dystonia (e.g., involuntary muscle spasms of the tongue, neck, back, or eyes, or life-threatening laryngeal spasm), akathisia (i.e., motor restlessness), and parkinsonian symptoms (e.g., rigidity, tremor, and bradykinesia).

Long-term medication use may also have a negative effect on a patient’s medical health. The risk of developing tardive dyskinesia (TD) (i.e., involuntary choreiform movements most commonly of the mouth, tongue, or upper extremities) is about 4% to 5% per year of exposure to conventional neuroleptics, and is associated with older age and a history of parkinsonian side effects. Atypical antipsychotics tend to have a lower risk of TD. Agranulocytosis occurs in about 0.4% of patients after 1 year of clozapine use.48 Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (consisting of hyperthermia, autonomic instability, change in mental status, elevated creatine phosphokinase [CPK], and rigidity) is a rare, but potentially lethal, complication of neuroleptic use. Among patients with prominent mood symptoms, potential effects (e.g., hypothyroidism, renal insufficiency, and cardiac effects) of medications such as lithium or the more rare effects of carbamazepine (e.g., aplastic anemia and agranulocytosis) must be monitored over the long-term.47

Substance Abuse

According to data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study, about 47% of people with schizophrenia have met criteria for substance abuse or dependence (33.7% with an alcohol disorder and 27.5% for other drug disorder), as compared to a rate of 17% for those in the general population.49 Alcohol is the most commonly used substance among those with schizophrenia; abuse of cocaine and cannabis is also frequent.50

Drug abuse and alcohol abuse are associated with homelessness, violent behavior, and medical co-morbidity among the chronically mentally ill. There is some evidence to suggest that these patients will display more EPS51 and tend to be less compliant with prescribed medication.50,52 Cannabis abuse is associated with more frequent and earlier relapses of psychotic symptoms among patients with schizophrenia.53

ACCESS TO MEDICAL CARE

Patients with chronic mental illness often have difficulty obtaining appropriate medical and preventive care. Even when they are able to access care, these patients may not receive optimal treatment and tend to have worse clinical outcomes than those in the general population.54–57 There are clear systems barriers to the provision of care for patients with severe mental illness (including insurance issues and a fragmented health care delivery system). Symptoms (such as disorganization or paranoia) may limit the patient’s ability to discuss or understand a medical problem. In addition, lower rates of medication adherence and poor overall self-care reduce effectiveness and outcomes of medical treatment.

Multiple studies over the past several years have examined potential disparities in the medical system for people with mental illness as compared to those in the general population. One review by Sullivan and colleagues58 concluded that people with DM and co-occurring mental illness were less likely than patients with only DM to be hospitalized after an emergency department visit, and similar results for DM-related care were documented in several other studies.59,60 Data from the CATIE trial noted that patients with schizophrenia have low rates of treatment for DM, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.57 Nonwhite women with schizophrenia appear to be especially vulnerable since they had even lower rates of treatment for DM and hyperlipidemia than nonwhite men.

In contrast, three recent studies demonstrated that patients with schizophrenia received high-quality medical care for treatment of cardiac risk factors61 and DM.62,63 However, some authors have advised caution in generalizing from their results since the data were obtained from patients treated in the setting of a large, urban academic center.61 In addition, a study by Jones and colleagues60 found that patients from rural areas of Iowa were less likely than those in urban areas to receive high-quality DM care. Further investigation is warranted to help close the existing gaps in quality of physical health treatment and outcomes for patients with mental illness.

TREATMENT FOR CHRONIC MENTAL ILLNESS

Before deinstitutionalization, the state hospital system provided housing and treatment for the chronically mentally ill. Since treatment subsequently moved out of hospitals and into community health care centers, further work has been done to coordinate care for patients in their own communities (through a combination of pharmacological, psychotherapeutic, and psychosocial modalities). The Program for Assertive Community Living (PACT) model was first developed in 1975 in Madison, Wisconsin.64 The program was designed to provide intensive support for patients and families around the clock, 7 days per week. The treatment team coordinated care, worked with community agencies, and taught skills needed to live in the community to help patients avoid hospitalization. A randomized, controlled trial of the program demonstrated that the program reduced hospitalization rates and led to improvement in psychiatric symptoms.65

More recent attempts to improve on this model are generally referred to as Assertive Community Treatment (ACT). In these programs, a multidisciplinary team follows a small group of patients in the community, provides medication and therapy, teaches skills for daily living, and coordinates the use of community services for the individual’s needs. Some programs focus on decreasing hospitalization rates, while others prioritize an improved quality of life or employment. Some programs have specialized resources for patients with severe personality disorders, substance use disorders, legal issues, and homelessness. Many studies have demonstrated that ACT programs can be effective at reducing hospitalization rates66,67 and can also be cost-effective, particularly when patients with chronic mental illness have high baseline hospitalization rates.67,68

Specific discussion of the diagnosis and psychopharmacological treatment of schizophrenia and other chronic mental illnesses are covered extensively in other chapters of this textbook. In brief, the evaluation of a patient with chronic mental illness depends on a thorough psychiatric evaluation, a mental status examination, a physical examination, a review of the medical and psychiatric history, and contact with family or others who can provide history to arrive at a clear diagnosis and treatment plan. A multidisciplinary team should work together to create a goal-oriented plan with clear interventions and expected outcomes. In addition, treaters must work closely with primary care physicians to monitor and prevent medical illnesses.69

Antipsychotic medication is the foundation for the psychopharmacological treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Evidence suggests that early intervention with antipsychotic medications is associated with improved outcome.2,70 Side effects of the conventional antipsychotics (such as parkinsonian symptoms and akathisia), as well as limited improvement in negative symptoms, have led to the more consistent use of atypical antipsychotics as the first-line treatment for schizophrenia. Clozapine has been shown to be more effective than conventional neuroleptics in treatment-resistant patients.71 The use of long-acting injectable medications is also a reasonable alternative for patients who have frequent relapses due to medication noncompliance.

Nonpharmacological treatments include psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral treatment, and family therapy. Although psychodynamic psychotherapy alone is not a sufficient treatment for schizophrenia, there is some evidence to suggest that supportive forms of psychotherapy (when focused on coping skills, problem-solving, and medication compliance) do lead to improvements in symptoms.72 In addition, there is strong support for cognitive-behavioral approaches.73 One type of program emphasizes social skills and utilizes psychosocial group treatment,74 and the other focuses on individual treatment to decrease hallucinations and delusions by teaching the patient to reality-test his or her psychotic symptoms and practice strategies for coping with these symptoms.75 Family therapy includes various behavioral and psychoeducational interventions; these have been shown to decrease rates of psychotic relapse and hospitalization among patients with schizophrenia as compared to routine outpatient care in some studies.76

Less than 20% of chronically mentally ill patients hold jobs in the community.76 Supportive employment programs provide individualized placement and support and aim to help patients gain competitive employment. Though evidence is lacking with regard to promotion beyond entry-level positions, and program dropout rates are high, these programs have been more successful at increasing employment opportunities than standard group skills training or vocational rehabilitation.

THE RECOVERY MODEL

A relatively recent development in the treatment of those with chronic mental illness has been the elaboration of a recovery model.77 A somewhat contentious concept, the recovery model refers to a process of focusing on the experience of patients and how to help individuals achieve optimal function. Originally promoted by consumer advocacy groups, such as the National Association of the Mentally Ill (NAMI), the recovery model focuses on such issues as destigmatization, self-empowerment, autonomy, goal orientation, and instilling hope. In addition to pharmacotherapy, interven-tions may involve individual symptom management (often in a cognitive-behavioral framework), assertive community treatment, employment counseling, supported employment, family therapy and education, and adjunctive substance abuse treatment. Critics of the recovery model have pointed to a relative lack of outcome data (e.g., few patients recover completely from the symptoms of illness from a medical standpoint) while proponents argue that recovery describes a patient-centered process aimed at optimal individual function that does not assume remission or cure.

1 Breier A, Schreiber J, Dyer J, et al. National Institute of Mental Health longitudinal study of chronic schizophrenia: prognosis and predictors of outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:239-246.

2 Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(3):241-247.

3 Goff DC, Gudeman JE. The person with chronic mental illness. In Nicholi AM, editor: The Harvard guide to psychiatry, ed 3, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1999.

4 Wu EQ, Birnbaum HG, Shi L, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(9):1122-1129.

5 Goffman E. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1963.

6 Pickenhagen A, Sartorius N. Annotated bibliography of selected publications and other materials related to stigma and discrimination because of mental illness and intervention programmes fighting it. Geneva: World Psychiatric Association, 2002.

7 Grob GN. Mental institutions in America: social policy to 1875. New York: Free Press, 1973.

8 Lamb HR, Bachrach LL. Some perspectives on deinstitutionalization. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1039-1045.

9 Appelbaum PS. Least restrictive alternative revisited: Olmstead’s uncertain mandate for community-based care. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(10):1271-1280.

10 Satin DG. Erich Lindemann: the humanist and the era of community mental health. Proc Am Philos Soc. 1982;126(3):327-346.

11 Bierer MF, Lafayette JM. Approach to the homeless patient. In Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, editors: The Massachusetts General Hospital guide to primary care psychiatry, ed 2, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

12 Monahan J. “A terror to their neighbors”: beliefs about mental disorder and violence in historical and cultural perspective. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1992;20(2):191-195.

13 Teplin LA. Criminalizing mental disorder. The comparative arrest rate of the mentally ill. Am Psychol. 1984;39(7):794-803.

14 Link BG, Stueve A, Phelan J. Psychotic symptoms and violent behaviors: probing the components of “threat/control-override” symptoms. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33(suppl 1):S55-S60.

15 Swanson JW, Holzer CE, Ganju VK, et al. Violence and psychiatric disorder in the community: evidence from the epidemiologic catchment area surveys. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1990;41:761-770.

16 Frankle W, Shera D, Berger-Hershkowitz H, et al. Clozapine-associated reduction in arrest rates of psychotic patients with criminal histories. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(2):270-274.

17 Glazer W, Dickson R. Clozapine reduces violence and persistent aggression in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 3):8-14.

18 Newman SC, Bland RC. Mortality in a cohort of patients with schizophrenia: a record linkage study. Can J Psychiatry. 1991;36:239-245.

19 Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office of Health and Human Services Department of Mental Health (DMH): Mortality report 1998-1999, Boston, 2001.

20 Department of Mental Health Central Massachusetts Area Office: Morbidity study: medical illnesses of Central Massachusetts area DMH residential clients, Worcester, MA, 2001.

21 Meyer JM, Nasrallah HA, McEvoy JP, et al. The Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial: clinical comparison of subgroups with and without the metabolic syndrome. Schizophr Res. 2005;80(1):9-18.

22 McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: baseline results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophr Res. 2005;80(1):19-32.

23 Homel P, Casey D, Allison DB. Changes in body mass index for individuals with and without schizophrenia, 1987-1996. Schizophr Res. 2002;55:277-284.

24 Dickerson FB, Brown CH, Kreyenbuhl JA, et al. Obesity among individuals with serious mental illness. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(4):306-313.

25 Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller AL, et al. Physical health monitoring of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1334-1349.

26 Nasrallah HA. Metabolic findings from the CATIE trial and their relation to tolerability. CNS Spectra. 2006;11(7 suppl 7):32-39.

27 Allison DB, Mentore JL, Heo M, et al. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1686-1696.

28 Allison DB, Casey ED. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a review of the literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 7):22-31.

29 Bustillo JR, Buchanan RW, Irish D, et al. Differential effect of clozapine on weight: a controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:817-819.

30 Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, et al. Clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:255-262.

31 Drieling T, Biedermann NC, Scharer LO, et al: Psychotropic drug-induced change of weight: a review, Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr, February 16, 2006.

32 Dixon L, Weiden P, Delahanty J, et al. Prevalence and correlates of diabetes in national schizophrenia samples. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:903-912.

33 Citrome L, Jaffe A, Levine J, et al. Incidence, prevalence and surveillance for diabetes in New York state psychiatric hospitals, 1997-2004. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(8):1132-1139.

34 Henderson DC, Cagliero E, Gray C, et al. Clozapine, diabetes mellitus, weight gain, and lipid abnormalities: a five-year naturalistic study. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:975-981.

35 Sernyak MJ, Leslie DL, Alarcon RD, et al. Association of diabetes mellitus with use of atypical neuroleptics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(4):561-566.

36 Koller EA, Doraiswamy PM. Olanzapine-associated diabetes mellitus. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22:841-852.

37 Henderson DC, Cagliero E, Copeland PM, et al. Glucose metabolism in schizophrenia patients treated with atypical antipsychotics: a frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test and minimal model analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;67(5):789-797.

38 Newcomer JW, Haupt DW, Fucetola R, et al. Abnormalities in glucose regulation during antipsychotic treatment of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:337-346.

39 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of current cigarette smoking among adults and changes in prevalence of current and some day smoking: United States, 1996-2001. JAMA. 2003;289(18):2355-2356.

40 Hughes J. Prevalence of smoking among psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:993-997.

41 Kelly C, McCreadie R. Cigarette smoking and schizophrenia. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2000;6:327-331.

42 Dolan SL, Sacco KA, Termine A, et al. Neuropsychological deficits are associated with smoking cessation treatment failure in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;70(2-3):263-275.

43 Zammit S, Allebeck P, Dalman C, et al. Investigating the association between cigarette smoking and schizophrenia in a cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(12):2216-2221.

44 George TP, Vessicchio JC, Termine A, et al. A placebo controlled trial of bupropion for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:53-61.

45 Volavka J, Convit A, Czobor P, et al. HIV seroprevalence and risk behaviors in psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatry Res. 1991;39:109-114.

46 Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:31-37.

47 Henderson DC, Goff DC. Antipsychotic drugs. In: Stern TA, Herman JB, editors. Psychiatry update and board preparation. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000.

48 Alvir JM, Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, et al. Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. Incidence and risk factors in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(3):162-167.

49 Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. JAMA. 1990;264(19):2511-2518.

50 Dixon L. Dual diagnosis of substance abuse in schizophrenia: prevalence and impact on outcomes. Schizophr Res. 1999;35:S93-S100.

51 Potvin S, Pampoulova T, Mancini-Marie A, et al. Increased extrapyramidal symptoms in patients with schizophrenia and a comorbid substance use disorder. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(6):796-798.

52 Margolese HC, Malchy L, Negrete JC, et al. Drug and alcohol use among patients with schizophrenia and related psychoses: levels and consequences. Schizophr Res. 2004;67(2-3):157-166.

53 Linszen DH, Dingemans PM, Lenior ME. Cannabis abuse and the course of recent-onset schizophrenic disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(4):273-279.

54 Goff DC, Sullivan LM, McEvoy JP, et al. A comparison of ten-year cardiac risk estimates in schizophrenia patients from the CATIE study and matched controls. Schizophr Res. 2005;80(1):45-53.

55 Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, et al. Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2000;283:506-511.

56 Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Desai MM, et al. Quality of preventive medical care for patients with mental disorders. Med Care. 2002;40:129-136.

57 Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

58 Sullivan G, Han X, Moore S, et al. Disparities in hospitalization for diabetes among persons with and without co-occurring mental disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(8):1126-1131.

59 Frayne SM, Halanych JH, Miller DR, et al. Disparities in diabetes care: impact of mental illness. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2631-2638.

60 Jones LE, Clarke W, Carney CP. Receipt of diabetes services by insured adults with and without claims for mental disorders. Med Care. 2004;42:1167-1175.

61 Weiss AP, Henderson DC, Weilberg JB. Treatment of cardiac risk factors among patients with schizophrenia and diabetes. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(8):1145-1152.

62 Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, et al. Disparities in diabetes care in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1584-1590.

63 Dixon LB, Kreyenbuhl JA, Dickerson FB, et al. A comparison of type 2 diabetes outcome among persons with and without severe mental illnesses. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:892-900.

64 Stein LI, Test MA. Alternative to mental hospital treatment. I. Conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37:392-397.

65 Marx AJ, Test MA, Stein LL. Extrahospital management of severe mental illness: feasibility and effects of social functioning. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1973;29:505-511.

66 Udechuku A, Olver J, Hallam K, et al. Assertive community treatment of the mentally ill: service model and effectiveness. Australas Psychiatry. 2005;13(2):129-134.

67 Bond GR, Miller LD, Krumwied RD, et al. Assertive case management in three CMHCs: a controlled study. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39:411-418.

68 Dixon L. Assertive community treatment: twenty-five years of gold. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(6):759-765.

69 Goff DC, Cather C, Evins AE, et al. Medical morbidity and mortality in schizophrenia: guidelines for psychiatrists. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(2):183-194.

70 Loebel AD, Lieberman JA. Duration of psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:1183-1188.

71 Kane JM, Honigfeld G, Singer J, et al. Clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenics. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24(1):62-67.

72 Tarrier N, Beckett R, Harwood S, et al. A trial of two cognitive-behavioural methods of treating drug-resistant residual psychotic symptoms in schizophrenic patients: I. Outcome. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:524-532.

73 Penn DL, Mueser KT, Tarrier N, et al. Supportive therapy for schizophrenia: possible mechanisms and implications for adjunctive psychosocial treatments. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(1):101-112.

74 Liberman RP, Spaulding WD, Corrigan PW. Cognitive-behavioural therapies in psychiatric rehabilitation. In: Hirsch SR, Weinberger DR, editors. Schizophrenia. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Science, 1995.

75 Cather C. Functional cognitive-behavioural therapy: a brief, individual treatment for functional impairments resulting from psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(5):258-263.

76 Bustillo JR, Lauriello J, Horan WP, et al. The psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia: an update. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:163-175.

77 Andresen R, Oades L, Caputi P. The experience of recovery from schizophrenia: towards an empirically validated stage model. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2003;37(5):586-594.