Respiratory Emergencies

Edited by Anne-Maree Kelly

6.1 Upper respiratory tract

Weng Hoe Ho and Ken Ooi

Introduction

The upper respiratory tract extends from the mouth and nose to the carina. It comprises a relatively small area anatomically, but is of vital importance. The majority of presentations are not life threatening, however, those that are require immediate evaluation or treatment.

Emergent conditions are those likely to compromise the airway. Protection and maintenance of airway, breathing and circulation (the ABCs) take precedence over history taking, detailed examination or investigations. Possible causes of airway obstruction are listed in Table 6.1.1.

Table 6.1.1

Causes of upper airway obstruction

Altered conscious state

Head injury

Cerebrovascular accident

Drugs and toxins

Metabolic – hypoglycaemia, hyponatraemia, etc.

Foreign bodies

Infections

Tonsillitis

Peritonsillar abscess (quinsy)

Epiglottitis

Ludwig’s angina

Other abscesses and infections

Trauma

Blunt or penetrating trauma resulting in oedema or haematoma formation

Uncontrolled haemorrhage

Thermal injuries

Inhalation burns

Neoplasms

Larynx, trachea, thyroid

Allergic reactions

Anaphylaxis

Angioedema

Anatomical

Tracheomalacia – congenital or acquired (secondary to prolonged intubation)

Other congenital malformations

Acute on chronic causes

Patients with chronic narrowing of the airway (e.g. due to tracheomalacia) may present worsening obstruction with an acute upper respiratory tract illness or injury

Non-urgent presentations include rash or facial swelling not involving the airway, sore throat in a non-toxic patient and complaints that have been present for days or weeks with no recent deterioration. Pharyngitis and tonsillitis are common causes for presentation in both paediatric and adult emergency practice.

Triage and initial evaluation

Initial evaluation should be aimed at differentiating those patients needing urgent management to prevent significant morbidity and mortality from those needing less urgent treatment. Triage must be based on the chief complaint and on vital signs since the same clinical presentation may result from a range of pathologies. For example, stridor can be due to trauma, infection, drug reactions or anatomical abnormalities, such as tracheomalacia.

Symptoms and signs of airway obstruction include dyspnoea, stridor, altered voice, dysphonia and dysphagia. Evidence of increased work of breathing includes subcostal, intercostal and suprasternal retraction, flaring of the nasal alar as well as exhaustion and altered mental state. The presence of these signs may vary with age and accompanying conditions. Cyanosis is a late sign.

Further examination will be directed by the presenting complaint and initial findings and includes:

Upper-airway obstruction

Upper-airway obstruction may be acute and life threatening or may have a more gradual onset. It is essential that the adequacy of the airway is assessed first. Any emergency interventions that are required to maintain the airway should be instituted before obtaining a detailed history and examination. This may range from relieving the obstruction to providing an alternative airway.

Pathology

Obstruction may be physiological with the patient unable to maintain and protect an adequate airway due to a decreased conscious state. Despite the plethora of possible causes, the initial treatment of securing the airway is the same regardless of the cause. Mechanical obstruction may be due to pathology within the lumen (aspirated foreign body), in the wall (angio-oedema, tracheomalacia) or by extrinsic compression (Ludwig’s angina, haematoma, external burns). Obstruction may be due to a combination of physiological and mechanical causes. A summary of potential causes of upper airway obstruction is provided in Table 6.1.1.

Clinical investigations

Investigations are secondary to the assessment of and/or provision of an adequate airway. Once the airway has been assessed as secure, the choice of investigations is directed by the history and examination.

Endoscopy

Direct laryngoscopy by an experienced operator is the single most important manoeuvre in patients with acute upper airway obstruction. It may concurrently form part of the assessment, investigation or treatment. By visualizing the laryngopharynx and upper larynx, the cause of the obstruction can be seen. Any foreign bodies may be removed or, if necessary, a definitive airway, such as an endotracheal tube, introduced. In the case of the stable patient with an incomplete obstruction, this should only be attempted when there are full facilities available for intubation and provision of a surgical airway. It may be more appropriately deferred until expert airway assistance is available.

Bronchoscopy may be required to assess the trachea and distal upper airway but it is not part of the initial resuscitation. In the stable patient, it is more appropriate to transfer the patient to the operating suite or ICU for this procedure.

Blood tests

Some blood tests may be useful in guiding further management. These include full blood count, arterial blood gases and blood cultures. Those required will be guided by the clinical presentation. Initial treatment in the emergency department should not await their results.

Imaging

Neck X-rays

A lateral soft tissue X-ray of the neck is sometimes helpful once the patient has been stabilized. Metallic or bony foreign bodies, food boluses or soft tissue masses may be seen. A number of subtle radiological signs have been described for epiglottitis (Table 6.1.2).

Table 6.1.2

Radiological findings in adult epiglottitis

| The ‘thumb’ sign | Oedema of the normally leaf-like epiglottis resulting in a round shadow resembling an adult thumb. The width of the epiglottis should be less than one-third the anteroposterior width of C4. In adults with epiglottitis, the width of the epiglottis is usually>9 mm |

| The vallecula sign | Progressive epiglottic oedema resulting in narrowing of the vallecula. This normally well-defined air pocket between the base of the tongue and the epiglottis may be partially or completely obliterated |

| Swelling of the aryepiglottic folds | |

| Swelling of the arytenoids | |

| Loss of the vallecular air space | |

| Prevertebral soft tissue swelling | The width of the prevertebral soft tissue should be less than half the anteroposterior width of C4 |

| Hypopharyngeal airway widening | The ratio of the width of the hypopharyngeal airway to the anteroposterior width of C4 should be less than 1.5 |

Computed tomography

In the patient with a mechanical obstruction, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck and upper thorax may be helpful in diagnosing the cause of the obstruction as well as the extent of any local involvement. It may aid in planning further management, especially if surgical intervention is indicated, for example for a retrothyroid goitre or head and neck neoplasm.

Treatment

Management initially consists of securing the airway. This is discussed in more detail elsewhere in this book, but simple interventions include chin lift or jaw thrust and an oropharyngeal airway. More sophisticated procedures, such as the laryngeal mask or endotracheal tube insertion or surgical airway, may be required.

A surgical airway is rarely necessary in the emergency department, although it is important that equipment is available and that the techniques have been practised. These include needle insufflation and cricothyrostomy. A number of commercial kits, such as the Mini-trach II and the Melker Emergency Cricothyroidotomy Catheter Set, are available. Further management will depend on the underlying cause.

Further treatment will be dictated by the underlying pathology.

Foreign body airway obstruction

Foreign body aspiration is often associated with an altered conscious state, for example in alcohol or drug intoxication, cerebrovascular accident (CVA) or dementia. Elderly patients with dentures are at increased risk.

Laryngeal foreign bodies are almost always symptomatic and are more likely to cause complete obstruction than foreign bodies below the epiglottis. Foreign bodies in the oesophagus are an uncommon cause of airway obstruction but, if lodged in the area of the cricoid cartilage or the tracheal bifurcation, they can compress the airway causing partial airway obstruction. Oesophageal foreign bodies may also become dislodged into the upper airway.

Treatment

In the management of incomplete airway obstruction with adequate gas exchange, care should be taken not to convert partial obstruction into complete obstruction by overzealous intervention.

Awake laryngoscopy can be performed to visualize the foreign body and remove it. The management of complete airway obstruction depends on the conscious level of the patient.

In conscious patients, the Heimlich manoeuvre (or abdominal thrust) is one recommended technique for dislodgement of a foreign body. The rescuer stands behind the patient placing clenched fists over the patient’s upper abdomen well clear of the xiphisternum. A short sharp upward thrust is made to force the diaphragm up and expel the foreign body. There is a risk of injury to internal organs and thus should only be done by rescuers who have been trained in the technique. Chest thrusts may be more effective in obese patients if the rescuer is unable to encircle the patient’s abdomen. Chest thrusts may also be used in children or in pregnant women. Patients who are asymptomatic after uncomplicated removal of a foreign body should be observed for a time in the emergency department and if they remain well may be discharged home.

In the unconscious patient direct laryngoscopy should be performed before bag/valve/mask ventilation. This prevents the foreign body from being moved from a supraglottic to an intraglottic position. If no foreign body is visualized, the patient should be intubated and ventilated. If the patient cannot be ventilated due to airway resistance, the endotracheal tube should be advanced maximally. This aims to convert a complete tracheal obstruction to a main stem bronchus obstruction. The foreign body can then be removed in the operating theatre.

Blunt trauma

Laryngotracheal trauma is rare, comprising 0.3% of all trauma presenting to emergency departments. The upper airway is relatively protected against trauma since the larynx is mobile and the trachea is compressible and because the head and mandible act as shields. Blunt trauma may be difficult to diagnose as external examination may be normal and there may be distracting head or chest injuries.

Mechanisms of injury

‘Clothes-line injuries’ involve cyclists or other riders hitting fences or cables. Direct trauma from assaults, sporting equipment or industrial accidents also occurs. Suicide attempts by hanging may cause traumatic injuries to the neck as well as airway obstruction due to the ligature. ‘Dashboard injuries’ occur when seatbelts are not worn, with sudden deceleration resulting in hyperextension of the neck and compression of the larynx between the dashboard and cervical spine.

Pathology

The most common laryngeal injury is a vertical fracture through the thyroid cartilage. Fractures of the hyoid bone and cricoid cartilage also occur and may be found in cases of manual or ligature strangulation. The cricothryoid ligament and the vocal cords may be ruptured and the arytenoids dislocated. Complete cricotracheal transection may occur. Up to 50% of patients sustaining significant blunt airway trauma have a concurrent cervical spine injury.

Clinical features

Tracheal or laryngeal injury should be suspected if aphonia, hoarseness, stridor, dysphagia or dyspnoea occur. Patients may present with complete obstruction or may deteriorate rapidly after arrival. There may be minimal external evidence of injury or the larynx may be deformed or tender and there may be subcutaneous emphysema. It is important to check for associated head, chest and cervical spine injuries.

Clinical investigations

Endoscopy

Both laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy may be required. This should be performed in the operating theatre, as urgent surgical intervention may be indicated.

Imaging

Plain X-ray

X-rays should only be considered if the patient is stable with adequate ventilation. Lateral soft-tissue X-rays of the neck may provide information about airway patency, subcutaneous or soft-tissue emphysema and fractures of the hyoid and larynx. Elevation of the hyoid bone indicates cricotracheal separation. Plain X-rays may also confirm the presence of a foreign body. Cervical spine X-rays should be considered due to the association between upper airway injuries and cervical spine injuries. Chest X-rays may show signs of trauma and subcutaneous or mediastinal emphysema.

CT

CT of the neck is useful in assessing the extent of injuries to larynx, oesophagus, cervical spine and adjacent structures but should only be considered once the patient is stabilized.

A classification system for severity of blunt upper airway injury based on endoscopic and radiological findings has been developed (Table 6.1.3).

Table 6.1.3

Grading of blunt laryngeal injury

| Grade | Endoscopic and radiological findings |

| I | Minor laryngeal haematoma without detectable fracture |

| II | Oedema, haematoma or minor mucosal disruption without exposed cartilage, or non-displaced fractures on CT |

| III | Massive oedema, tears, exposed cartilage, immobile cords |

Treatment

Airway management with protection of the cervical spine is essential. Fibreoptic bronchoscopic intubation is preferable to minimize complications, such as laryngeal disruption, laryngotracheal separation or creating a false tracheal lumen. Cricothyrostomy is relatively contraindicated due to the altered anatomy. Emergency tracheostomy may even be required, ideally performed in the operating theatre. Early ENT involvement is important and indications for surgical exploration include airway obstruction requiring tracheostomy, uncontrolled subcutaneous emphysema, extensive mucosal lacerations with exposed cartilage as identified on bronchoscopic or laryngoscopic examination, vocal cord paralysis and grossly deformed, multiple or displaced fractures of the larynx, thyroid cartilage or cricoid cartilage.

Prognosis

Mortality rates depend on the location of the injury, ranging from 11% for isolated fractures of the thyroid cartilage to 50% for injuries involving the cricoid cartilage, bronchi or intrathoracic trachea. Asphyxiation is the most common cause of death in blunt laryngeal trauma.

Penetrating trauma

Mechanism

Penetrating injuries may be secondary to assault or to sporting or industrial accidents. Other causes include eroding head and neck malignancies or post-radiotherapy. A focused history is mandatory.

Clinical features

Penetration of the airway should be suspected if there is difficulty breathing, hoarseness or change in voice, stridor, pain on speaking, subcutaneous emphysema, haemoptysis or bubbling from the wound. Penetrating airway injury is often associated with great vessel or pulmonary injuries. Uncontrolled haemorrhage may lead to exsanguination as well as compromising the airway and requires prompt surgical intervention.

Clinical investigation

As for blunt trauma (see above).

Treatment

Airway management with protection of the cervical spine is essential. Airway management is as for blunt trauma (see above). Early involvement of relevant surgical specialties is a priority.

Thermal injury

Pathology and pathophysiology

Burns may affect the airway by way of facial and perioral swelling, laryngeal oedema or constricting circumferential neck burns. Smoke inhalation occurs in about 25% of burn victims and may cause bronchospasm, retrosternal pain and impaired gas exchange.

Clinical features

External examination may show evidence of burns. Carbonaceous material in the mouth, nares or pharynx suggests the possibility of upper airway thermal injury. If the patient presents with stridor or hoarseness, early intubation is essential because of the danger of increasing airway oedema and rapid progression to airway obstruction. Smoke inhalation may be associated with carbon monoxide poisoning and, in the setting of domestic or industrial fires, cyanide poisoning should also be considered.

Clinical investigations

Endoscopy

Endoscopy includes both laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy, performed in the operating theatre, as urgent surgical intervention may be required.

Imaging

Chest X-ray may show evidence of burn- associated acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Infections

Introduction

Infections may involve the upper respiratory tract directly or adjacent structures. They range from the common and trivial to the rare and potentially life threatening. Croup and epiglottitis usually occur in children, but may be seen in adults. Acute respiratory infections are the most frequent reason for seeking medical attention in the USA and are associated with up to 75% of total antibiotic prescriptions there each year. Unnecessary antibiotic use can cause a number of adverse effects including allergic reactions, gastrointestinal upset, yeast infections, drug interactions, an increased risk of subsequent infection with drug resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae and added costs of over-treatment.

Non-specific upper airway infections

Upper airway infections are generally diagnosed clinically. Symptom complexes where the predominant complaint is of sore throat are labelled pharyngitis or tonsillitis and, where the predominant symptom is cough, bronchitis. Acute respiratory symptoms in the absence of a predominant sign are typically diagnosed as ‘upper-respiratory-tract infections’.

Each of these syndromes may be caused by a multitude of different viruses and only occasionally by bacteria. Most cases resolve spontaneously within 1–2 weeks. Bacterial rhinosinusitis complicates about 2% of cases and should be suspected when symptoms have lasted at least 7 days and include purulent nasal discharge and other localizing features. High-risk patients for developing bacterial rhinosinusitis or bacterial pneumonia include infants, the elderly and the chronically ill. Treatment should be symptomatic only. Antibiotic treatment does not enhance illness resolution nor alter the rates of complications.

Pharyngitis/tonsillitis

Sore throat is one of the top 10 presenting complaints to emergency departments in the USA. The differential diagnosis is large and includes a number of important conditions (Table 6.1.4).

Table 6.1.4

Differential diagnosis of sore throat in the adult

Infective pharyngitis

Bacterial: Group A beta-haemolytic streptococcus most common pathogen. Diphtheria should be considered in patients with membranous pharyngitis

Viral: including Epstein–Barr virus and herpes simplex virus

Traumatic pharyngitis (exposure to irritant gases)

Non-specific upper respiratory tract infection

Quinsy (peritonsillar abscess)

Epiglottitis

Ludwig’s angina

Parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal abscesses

Gastro-oesophageal reflux

Oropharyngeal or laryngeal tumour

Pharyngitis has a wide range of causative viral and bacterial agents, most of which produce a self-limited infection with no significant sequelae. Group A beta-haemolytic streptococcus (Strep. pyogenes) (GABHS) is responsible for 5–15% of cases of pharyngitis in adults and, rarely, can trigger post-infectious syndromes of post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis and acute rheumatic fever.

Clinical investigations

Clinical diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis is unreliable. Clinical prediction rules have been developed to help identify patients in whom evaluation with a throat culture or rapid antigen-detection test (RADT) is warranted. The most reliable clinical predictors for GABHS are the Centor criteria. One point each is allocated for the features of tonsillar exudate, tender anterior cervical lymphadenopathy or lymphadenitis, absence of cough and history of fever>38°C. One point is deducted for age>45 years. For a score of 0–1, no further testing or antibiotics is recommended. For scores of 2–3, further testing is recommended with antibiotics only given to patients with positive RADT or cultures. For a score of 4, empirical antibiotic treatment and/or further testing are advised.

Rapid antigen tests have sensitivities ranging between 65 and 97%. Throat cultures take 2–3 days and may give false-positive results from asymptomatic carriers with concurrent non-GABHS pharyngitis. Serological testing is not useful in the acute treatment of pharyngitis but is useful in the diagnosis of rheumatic fever.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends throat cultures for children and adolescents with appropriate clinical criteria (fever, tonsillar exudates, tender cervical lymphadenopathy, absence of cough) but negative rapid antigen test. Adults with a negative RADT will not require cultures due to a lower incidence of GABHS pharyngitis and lower risk of rheumatic fever. Testing is not recommended for patients with clinical features suggestive of a viral aetiology (e.g. cough, oral ulcers, rhinorrhoea and hoarseness).

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is an uncommon cause of pharyngitis and may be asymptomatic. It is seen in persons who practice receptive oral sex. N. gonorrhoeae pharyngitis is important to diagnose correctly both for appropriate treatment and because of the need to trace and treat contacts.

HIV is an unusual cause of pharyngitis but should be considered in high-risk populations. The acute retroviral syndrome may present with an Epstein–Barr virus mononucleosis-like syndrome.

Treatment

Timely use of appropriate antibiotics prevents the development of acute rheumatic fever, decreases the duration of symptoms and decreases the incidence of suppurative complications, such as otitis media and peritonsillar abscesses. However, empirical antibiotic treatment on the basis of symptoms alone results in overuse of antibiotics, increased costs and an increased rate of side effects from antibiotics. Antibiotics have not been shown to decrease the incidence of post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, which is related to the subtype of streptococcus.

First-line antibiotics include oral penicillin V, amoxicillin, cephalexin, clindamycin or clarithromycin for 10 days or a single dose of intramuscular penicillin G.

For uncomplicated pharyngeal gonorrhoea, ceftriaxone 125 mg IM as a single dose is the recommended treatment. Consideration should be given to concomitant treatment for Chlamydia if this has not been ruled out.

Most patients with pharyngitis are managed as outpatients. Airway compromise is rare as the nasal passages provide an adequate airway. Some patients who are toxic or dehydrated may need admission for IV hydration and antibiotics. Penicillin or amoxicillin remain the drugs of choice for streptococcal pharyngitis. Regarding adjuvant corticosteroid therapy, a recent Cochrane review of patients with pharyngitis treated with antibiotics concluded that those with adjuvant corticosteroid therapy were three times more likely to experience complete resolution of their sore throat symptoms by 24 hours compared to those taking placebo. In addition, corticosteroids improved the time to onset of symptom relief and the time to complete resolution of symptoms. Adverse events, relapse rates and recurrence rates were not different for corticosteroid compared to placebo groups.

Quinsy/peritonsillar abscess

Epidemiology and pathology

Peritonsillar infections occur between the palatine tonsil, its capsule and the pharyngeal muscles. Peritonsillar cellulitis may progress to abscess formation. Cellulitis responds to antibiotics alone, but differentiating between the cellulitis and abscess and identifying those who require drainage may be difficult. Peritonsillar abscesses occur most commonly in males between 20 and 40 years of age.

Clinical features, investigations and complications

Symptoms include progressively worsening sore throat (usually unilateral), fever and dysphagia. On examination, the patient may have a muffled ‘hot potato’ voice, trismus, drooling, a swollen red tonsil with or without purulent exudate and contralateral deviation of the uvula.

Clinical features do not always differentiate between quinsy and peritonsillar cellulitis. In such situations, imaging (e.g. CT), needle aspiration or trial of IV antibiotics help to differentiate between them.

Complications include airway obstruction and lateral extension into the parapharyngeal space.

Treatment

Antibiotic therapy should include cover for GABHS, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae and respiratory anaerobic species (Fusobacterium, Peptostreptococcus and Bacteroides). Appropriate antibiotics include penicillin V or clindamycin for patients allergic to penicillin.

Needle aspiration in experienced hands can be useful but has a 12% false-negative rate and carries the risk of damaging the carotid artery. Formal surgical drainage or tonsillectomy may be necessary.

Ludwig’s angina

Peripharyngeal ‘space’ infections have become rare in the post-antibiotic era but, of these, Ludwig’s angina or cellulitis of the submandibular space remains the most common. It was first described by Wilhelm Fredrick von Ludwig in 1836 and, at that time, was usually fatal because of rapid compromise to the airway. With prompt treatment, including IV antibiotics, the mortality rate has declined to less than 5%.

Pathogenesis and pathology

Ludwig’s angina is classically bilateral. Infection may spread rapidly into adjacent spaces including the pharyngomaxillary and retropharyngeal areas and the mediastinum. Ludwig’s angina is related to dental caries involving the mandibular molars or it may be associated with peritonsillar abscess, trauma to the floor of the mouth or mandible and recent dental work.

Cultures are usually polymicrobial and include viridans streptococci (40.9%), Staph. aureus (27.3%), Staph. epidermidis (22.7%) and anaerobes (40%), such as Bacteroides species.

Clinical features

Clinical features include toothache, halitosis, neck pain, swelling, fever, dysphagia and trismus.

Treatment and disposition

Treatment necessitates admission and careful airway management. This may include endotracheal intubation as abrupt obstruction can occur. Surgical drainage is indicated if the infection is suppurative or fluctuant.

The antibiotics of choice are high-dose penicillin plus metronidazole or clindamycin which should be administered IV.

Other abscesses

Parapharyngeal abscesses

Parapharyngeal abscess involves the lateral or pharyngomaxillary space. Presentation and treatment are similar to Ludwig’s angina, from which they may develop. As well as the complications of Ludwig’s angina, including airway obstruction and spread to contiguous areas, there is the added risk of internal jugular vein thrombosis and erosion of the carotid artery which has a mortality of 20–40%.

Retropharyngeal abscess

Retropharyngeal abscesses are more common in children below 5 years of age. In adults, they often result from foreign bodies or trauma. Presenting symptoms and signs include fever, odynophagia, neck swelling, drooling, torticollis, cervical lymphadenopathy, dyspnoea and stridor.

Lateral neck X-rays show widening of the prevertebral soft tissues and sometimes a fluid level. CT of the neck may help in determining the extent and in differentiating an abscess from cellulitis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), if available, is more sensitive than CT in assessing soft-tissue infections of the head and neck but demonstrates cortical bone poorly. Treatment requires admission, airway management, IV antibiotics and may include surgical drainage.

Epiglottitis

Epidemiology and pathology

Epiglottitis is becoming an adult disease although, in adults, there is significantly less risk to the airway than in children. The incidence of adult epiglottitis has remained relatively stable at 1–4 cases per 100 000 per year with a mortality of 7%. This may change over the next 10–20 years as vaccinated children grow into adolescents and adults.

Acute adult epiglottitis is often referred to as supraglottitis because inflammation is not confined to the epiglottis, but also affects other structures, such as the pharynx, uvula, base of tongue, aryepiglottic folds and false vocal cords.

H. influenzae has been isolated in 12–17% of cases and the high rate of negative blood cultures may reflect viral infections or prior treatment with antibiotics in cases that present late. Strep. pneumoniae, H. parainfluenzae and herpes simplex have also been isolated. Epiglottitis may also occur following mechanical injury, such as ingestion of caustic material, smoke inhalation and following illicit drug use (smoking heroin).

Clinical features

Sore throat and odynophagia are the most common presenting symptoms. Other symptoms include fever and muffled voice. Drooling and stridor are infrequent. Factors shown to be associated with an increased risk of airway obstruction include stridor, dyspnoea, preferred upright posture and short duration of symptoms.

Clinical investigations

A number of X-ray changes have been described in epiglottitis which are listed in Table 6.1.2.

Treatment

Antimicrobial therapy should provide cover against H. influenzae B, Strep. pneumoniae, beta-haemolytic streptococci and Staph. aureus. Third generation cephalosporins (ceftriaxone or cefotaxime) and antistaphylococcal agents active against methicillin-resistant Staph. aureus (MRSA) (e.g. clindamycin) should be used.

The role of steroids and nebulized or parenteral adrenaline (epinephrine) in airway management is controversial. Most adults can be treated conservatively without the need for an artificial airway.

6.2 Asthma

Anne-Maree Kelly and Wee Yee Lee

Introduction

Asthma is a major health problem worldwide, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality. The prevalence of asthma varies significantly between regions across the world. In Australasia, New Zealand and the UK, it is thought to affect about 20% of children and 10% of adults. Sufferers tend to present to emergency departments when their usual treatment plan fails to control symptoms adequately. The respiratory compromise caused can range from mild to severe and life threatening. For these patients, the main role of the emergency care is therapeutic. Other reasons for patients with asthma to attend emergency departments (EDs) include having run out of medication, having symptoms after a period of being symptom and medication free and a desire for a ‘second opinion’ about the management of their asthma. For this smaller group, the primary role is one of educating about the disease, of planning an approach to the current level of asthma symptoms and of referral to appropriate health professionals, e.g. respiratory physicians or general practitioners.

Epidemiology

Asthma is a major health problem in many countries, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality. Data from the Global Initiative for Asthma suggest that more than 300 million people in the world are currently affected by asthma. The cost in terms of long-term medications and lost school and work days is difficult to quantify, but would run to millions of dollars annually. Australasia, the UK and North America have a greater prevalence of asthma than the Middle East and some Asian countries. There is also considerable geographical variation in severity, with Australasia reporting the highest proportion of severe disease. The reason for this geographical variation is unclear, but may relate in part to ethnicity, rural versus metropolitan environment and air pollution. A number of epidemiological studies suggest that the prevalence and severity of asthma is slowly increasing worldwide.

Aetiology, pathophysiology and pathology

Asthma is characterized by hyperreactive airways and inflammation leading to episodic, reversible bronchoconstriction in response to a variety of stimuli. It is a complex immunologically-mediated disease. There is strong evidence that it is inherited, although no single gene is directly implicated. A polygenic basis is likely to account for asthma’s wide clinical spectrum.

Studies suggest that asthma sufferers may have abnormal immunological systems, innately hypersensistive airways and abnormal airway repair mechanisms. Environmental factors interact with this system to produce clinical disease.

Triggers of the immunological response (e.g. an extrinsic allergen, viral respiratory tract infection, pollutants, occupational exposures, emotion, exercise and drugs, such as aspirin and β-blockers) result in an exaggerated inflammatory response with activation of cell types including mast cells, eosinophils, basophils, Th-2 cells and natural killer cells. This leads to the release of primary mediators, including histamine and eosinophilic and neutrophilic chemotactic factors and secondary mediators, including leukotrienes, prostaglandins, platelet-activating factor, interleukins and cytokines. These result in bronchoconstriction via direct and cholinergic reflex actions, increased vascular permeability (resulting in oedema) and increased mucous secretions.

Studies suggest that airway remodelling occurs in asthma sufferers resulting in airways that are more hypersensitive than previously. It is postulated that this structural remodelling results in loss of lung function and loss of complete reversibility.

Clinical assessment

The aims of clinical assessment are confirmation of the diagnosis, assessment of severity and identification of complications.

History

Asthma is characterized by episodic shortness of breath, often accompanied by wheeze, chest tightness and cough. Symptoms may be worse at night, which is thought to be due to variations in bronchomotor tone and bronchial reactivity. Attacks may progress slowly over days or rapidly over minutes. Atypical presentation includes cough and decreased exercise tolerance.

Features suggesting an increased risk of life-threatening asthma include a previous life-threatening attack, previous intensive care admission with ventilation, requiring three or more classes of asthma medication, heavy use of β-agonists, repeated emergency department attendances in the last year and having required a course of oral corticosteroids within the previous 6 months. Behavioural and psychosocial factors have also been implicated in life-threatening asthma including non-compliance with medications, monitoring or follow up, self-discharge from hospital, frequent GP contact, psychiatric illness, denial, drug or alcohol abuse, obesity, learning difficulties, employment or income problems and domestic, marital or legal stressors. These should be sought in order to assess risk more accurately and plan management.

Examination

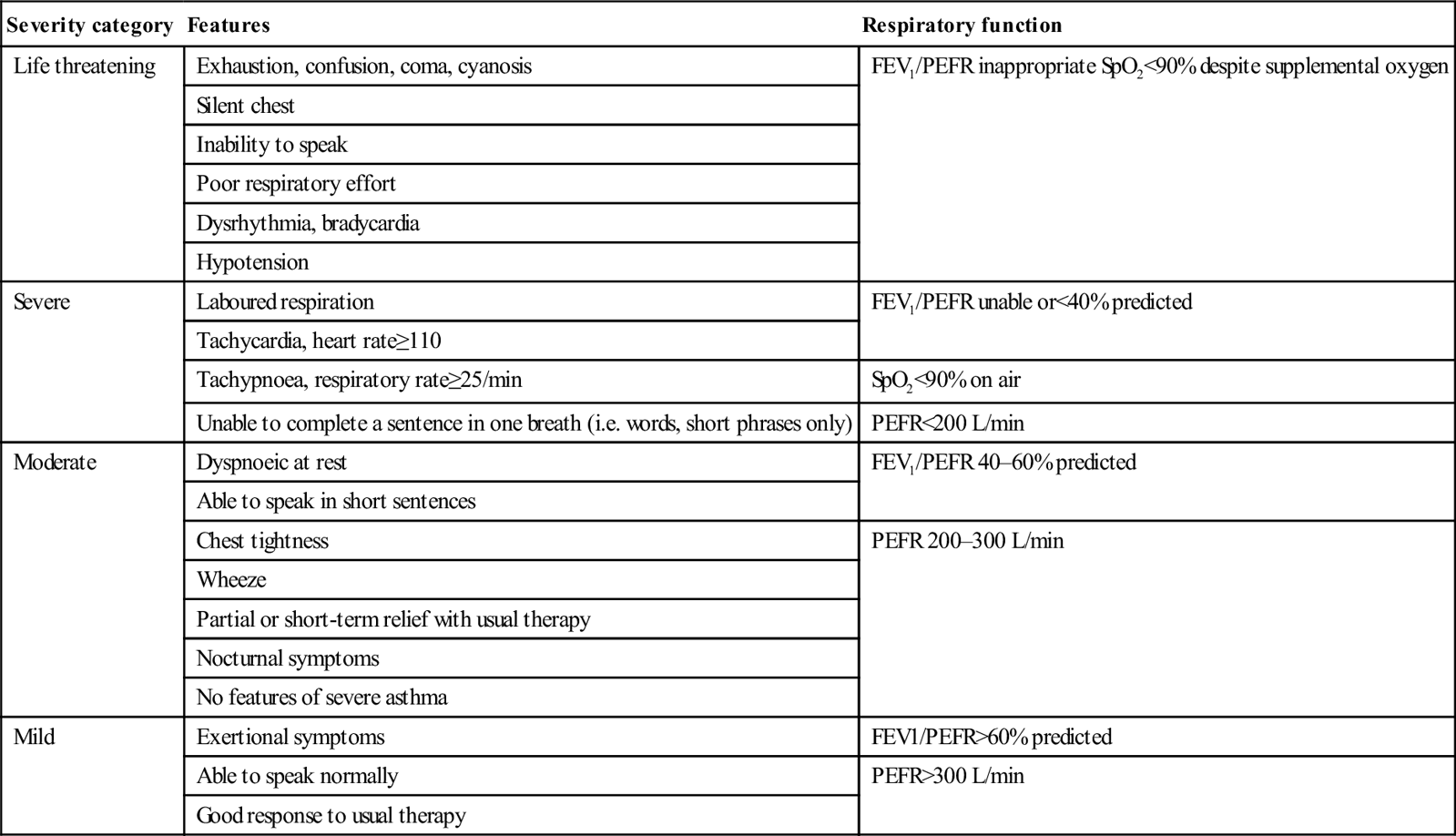

Physical findings vary with the severity of the attack and may range from mild wheeze and dyspnoea to respiratory failure. Findings indicative of more severe disease include an inability to speak normally, use of the accessory muscles of respiration, a quiet or silent chest on auscultation, restlessness or altered level of consciousness, oxygen saturation on room air of<93% and cyanosis. Clinical features are a good guide to the severity of attacks. Features of the major severity categories are summarized in Table 6.2.1. Pulsus paradoxus has been abandoned as an indicator of severity.

Table 6.2.1

Categorization of asthma severity based on clinical features

| Severity category | Features | Respiratory function |

| Life threatening | Exhaustion, confusion, coma, cyanosis | FEV1/PEFR inappropriate SpO2<90% despite supplemental oxygen |

| Silent chest | ||

| Inability to speak | ||

| Poor respiratory effort | ||

| Dysrhythmia, bradycardia | ||

| Hypotension | ||

| Severe | Laboured respiration | FEV1/PEFR unable or<40% predicted |

| Tachycardia, heart rate≥110 | ||

| Tachypnoea, respiratory rate≥25/min | SpO2<90% on air | |

| Unable to complete a sentence in one breath (i.e. words, short phrases only) | PEFR<200 L/min | |

| Moderate | Dyspnoeic at rest | FEV1/PEFR 40–60% predicted |

| Able to speak in short sentences | ||

| Chest tightness | PEFR 200–300 L/min | |

| Wheeze | ||

| Partial or short-term relief with usual therapy | ||

| Nocturnal symptoms | ||

| No features of severe asthma | ||

| Mild | Exertional symptoms | FEV1/PEFR>60% predicted |

| Able to speak normally | PEFR>300 L/min | |

| Good response to usual therapy |

Modified from Guidelines for Emergency Management of Adult Asthma, Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians, British Guideline on the Management of Asthma (SIGN) and Asthma Management Handbook (NAC) with permission.

Clinical investigations

Mild to moderate asthma

For mild and moderate asthma, investigations should be limited to pulmonary function tests (PEFR or FEV1). A chest X-ray is only indicated if examination of the chest suggests pneumothorax or pneumonia. Arterial blood gases are not useful in this group of patients.

Severe asthma

Assessment should include an assessment of PEFR if possible.

Chest X-ray

For severe asthma, a chest X-ray is necessary as localizing signs in the chest may be hard to detect.

Blood gas analysis

Blood gas analysis may be useful if the oxygen saturation is less than 92% on room air at presentation, if improvement is not occurring as expected and if the patient appears to be tiring. For those with severe asthma, arterial blood gases may show:

Blood gas analysis may also be helpful if intubation is being considered because of worsening respiratory failure. That said, their impact taken early in management is minimal and they should never be considered ‘routine’. There is increasing evidence that venous blood gases can accurately screen for arterial hypercarbia. Given the accuracy of pulse oximetry, venous blood gas analysis may be adequate for detecting acidosis and hypercarbia, avoiding significant discomfort for patients.

Blood tests

Full blood examination is usually not useful, as a mild-to-moderate leucocytosis may be present in the absence of infection. Electrolyte measurements may show a mild hypokalaemia, particularly if frequent doses of β-agonists have been taken.

Treatment

The emergency management of acute asthma varies according to severity, as defined by the clinical parameters above. The principles are to ensure adequate oxygenation, reverse bronchospasm and minimize the inflammatory response.

Mild asthma

Mild attacks are managed using inhaled β2-adrenergic agonists, such as salbutamol, by metered dose inhaler (MDI) or spacer, the commencement of inhaled corticosteroids if the patient is not already taking them and education about the disease and the proposed management and follow-up plan.

Moderate asthma

Patients with moderate attacks may require oxygen therapy titrated to achieve oxygen saturation in excess of 92%. The mainstays of therapy are inhaled β2-adrenergic agents (by MDI with a spacer or nebulizer) and systemic corticosteroids. The dosage of salbutamol is 5–10 mg by nebulizer or eight puffs by MDI and spacer, every 15 minutes for three doses. Corticosteroids are equally effective given by the oral or intravenous routes. The usual dose is 50 mg prednisolone orally or 250 mg hydrocortisone intravenously. Reassessment, including repeat pulmonary function tests, should occur at least 1 hour after the last dose of β2-agonist. This will guide further therapy and disposition decision making.

Patients with PEFR>70% best or predicted 1 hour after initial treatment may be discharged from the emergency department unless there are concerns about compliance or social circumstances, the patient has a history of brittle or near fatal asthma, discharge would occur overnight or the patient is pregnant. This group are likely to benefit from a longer period of observation and treatment, e.g. in an emergency observation or short stay unit. Those who fail to respond quickly usually require extended treatment. In these patients, the addition of ipratropium bromide (0.5 mg 4–6 hourly) may be considered, particularly in those taking long-acting β-agonists, in whom a degree of tolerance to bronchodilation with short-acting β2-agonists can occur.

For patients who are discharged, oral corticosteroids at a dose of 0.5–1 mg/kg/day, in addition to inhaled steroids at standard doses, should be continued for at least 5 days or until recovery. Oral steroids may then be withdrawn; tapering of dose is unnecessary.

Severe asthma

Patients should be managed in an area with close physiological monitoring.

Oxygen

Severe attacks require supplemental oxygen to achieve oxygen saturation in excess of 92%. Because of high respiratory rates, it is important to ensure adequate gas flow by the use of either a reservoir-type mask or a Venturi delivery system. High oxygen concentrations may be necessary.

Specific therapy

Patients should receive β2-agonist by nebulizer at the doses described above, plus oral or intravenous corticosteroids (e.g. prednisolone 50 mg daily orally or hydrocortisone 100 mg 6-hourly IV). Metered dose inhalers with spacers can be used in patients with exacerbations that are not life threatening. Continuous nebulization may be more effective than intermittent bolus nebulization in patients with poor response to initial therapy. There is no evidence of any difference in efficacy between salbutamol and terbutaline. Nebulized adrenaline (epinephrine) does not have significant benefit over selective agents. The addition of nebulized ipratropium (500 μg 2-hourly) is recommended. If patients fail to respond, an intravenous β2-agonist (e.g. salbutamol as a bolus of 250 μg followed by an infusion at 5–10 μg/kg/hour) and/or ventilatory support should be considered.

Ventilatory support

If ventilatory support is required for patients with an acceptable conscious state and airway protective mechanisms, non-invasive ventilation may be suitable. If the patient is unsuitable for or does not improve with non-invasive ventilation, endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation will be needed. Ketamine, which has been shown to be an effective bronchodilator, is the induction agent of choice. Care must be taken with ventilation, as severe air trapping can result in markedly raised intrathoracic pressure with cardiovascular compromise. A slow ventilation rate of 6–8 breaths/min with low volume ventilation and prolonged expiratory periods is recommended. To reduce the risk of barotrauma, permissive hypercapnia is allowed as long as adequate oxygenation is achieved.

Other agents

Magnesium

Magnesium can be administered IV or by nebulizer. It is postulated to have both bronchodilatory and anti-inflammatory effects.

With respect to IV magnesium, a Cochrane review suggests that there is no benefit from its use (in addition to standard therapy) in mild or moderate asthma, but that for severe asthma (FEV1<25% predicted) the addition of magnesium resulted in highly significant increases in FEV1 and reduced admission rates. No serious adverse reactions were noted in any of the studies.

The current recommendation is that a single dose of IV magnesium sulphate (1.2–2 g over 20 minutes) be considered in patients with:

Aminophylline

Although pooled studies and meta-analyses fail to show benefit in adults, there is anecdotal evidence that selected, rare patients who fail to respond to the above treatment may benefit from IV aminophylline (5 mg/kg loading dose over 20 minutes, followed by 0.3–0.6 mg/kg/h). It should not be used without specialist input and should be used with particular care in patients already taking oral xanthines at admission.

Leukotriene receptor antagonists

There is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation about the use of these agents in acute asthma.

Antibiotics

Routine prescription of antibiotics is not indicated.

Non-invasive ventilation (NIV)

In acute asthma, NIV has been shown to reduce airways resistance, bronchodilate, counter atelectasis, reduce the work of respiration and reduce the cardiovascular impact of changes in intrapleural and intrathoracic pressures caused by asthma. It does not, when used alone, improve gas exchange. An unrandomized study of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in combination with pressure support ventilation in patients with severe asthma found rapid correction of pH and improvement in ventilation at lower pressures than were necessary with mechanical ventilation. Other small studies also suggest that NIV may reduce the need for intubation in selected patients and result in faster improvement. NIV also appears to be associated with a lower risk of adverse events than endotracheal intubation. There are currently no guidelines governing the use of NIV in asthma, however, in suitable patients, a trial of NIV under closely supervised conditions would seem reasonable.

Heliox

Heliox is a blend of 70% helium and 30% oxygen. It has been postulated that it may have advantages in asthma because of its better gas flow dynamics. Small studies have had conflicting results and Cochrane review concluded that the existing evidence did not support the use of heliox in patients with acute severe asthma in the ED.

Ketamine

A potential benefit from cautious subinduction doses of ketamine in severe asthma has been suggested. The postulated mechanisms of action of ketamine in asthma are sympathomimetic effects, direct relaxant effects on bronchial smooth muscle, antagonism of histamine and acetylcholine and a membrane-stabilizing effect. There is only one randomized trial investigating the role of ketamine in acute asthma. It showed that, in doses with an acceptable incidence of dysphoria, ketamine did not confer benefit. For intubated patients, there is some preliminary evidence that ketamine infusion (bolus 1 mg/kg, followed by 1 mg/kg/h) may improve blood gas parameters. No outcome benefit has yet been demonstrated.

Anti-IgE therapy

Anti-IgE therapy (e.g. omalizumab) is used for severe chronic allergic asthma. Its role is the reduction of exacerbations. It has no role in acute management.

Disposition

Patients with mild disease can usually be discharged after treatment and the formulation of a treatment plan. For patients with moderate and severe asthma, bedside pulmonary function tests can be a useful guide to disposition decisions. Those with post-treatment PEFR>70% predicted/best after initial treatment can be discharged on appropriate therapy (see above). Those with PEFR 40–70% predicted/best require an extended period of observation and treatment (e.g. in an emergency observation unit) after which many will be suitable for discharge. Patients with life-threatening asthma or post-treatment PEFR<40% best/predicted require hospital admission. In addition, other factors should be considered in estimating the safety of discharge. These include history of a previous near-death episode, recent ED visits, frequent admissions to hospital, current or recent steroid use, sudden attacks, poor understanding or compliance, poor home circumstances and limited access to transport back to hospital in case of deterioration.

Indications for admission to an intensive care or high dependency unit include:

persisting or worsening hypoxia

persisting or worsening hypoxia

exhaustion/deteriorating respiratory effort

exhaustion/deteriorating respiratory effort

drowsiness, confusion, altered conscious state

drowsiness, confusion, altered conscious state

All discharged patients should have an asthma action plan to cover the following 24–48 hours, with particular emphasis on what to do if their condition worsens. They should also have a scheduled review, either in the hospital or with a general practitioner within that time. Discharge medications are as described above.

6.3 Community-acquired pneumonia

Mark Putland and Karen Robins- Browne

Introduction

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) represents a spectrum of disease from mild and self-limiting to severe and life threatening. The great majority of cases are treated in the community with oral antibiotics, many without radiological confirmation. In the emergency department, CAP is generally not a great diagnostic challenge but rather represents a challenge of separating the serious cases that require inpatient treatment and supportive care from the mild cases that can be managed with minimal expense to the community and minimal inconvenience to the patient at home. Infrequently, CAP presents with the need for urgent, life-saving interventions and critical care.

The chest X-ray (CXR) remains the gold standard diagnostic test for pneumonia. Ancillary tests including urinary antigen test (UAT), sputum and blood cultures, inflammatory markers, renal and liver function tests and blood counts have roles in selected cases. A rational approach to the use of pathology testing is required to avoid excess healthcare cost and to prevent inappropriate decisions based on spurious or misleading results.

Antibiotic management of CAP has changed little for some decades, although respiratory fluroquinolones, such as moxifloxacin and levofloxacin, have a role. In some patients, the emergence of drug resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae (DRSP) and community-acquired methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) present new challenges in management.

Recent years have seen the publication of comprehensive evidence-based guidelines from the British Thoracic Society (BTS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America and American Thoracic Society (IDSA/ATS) as well as similar documents from Japan, Sweden, Canada and other countries. The Australian Therapeutic Guidelines continue to provide up-to-date antibiotic guidelines for the Australian setting. There is mounting evidence that the use of a structured, guideline-based approach to CAP management improves mortality and that such guidelines should be adapted to local conditions.

Epidemiology

Rates of pneumonia are difficult to estimate due to issues of case definition and the fact that the majority of cases occur unstudied in the community. However, data from around the world suggest that the incidence is around 5–11/1000/year in 16–59 year olds and over 30/1000/year in those over 75 years old. Incidence of CAP requiring hospitalization in the UK is less than 5/1000/year and comprises probably less than 50% of CAP cases. On the other hand, CAP accounts for 8–10% of ICU medical admissions.

Rates of admission to ICU vary enormously around the world and probably represent resource availability and usage more than differences in disease severity. New Zealand studies report 1–3% of cases needing ICU while, in the UK, it is around 5% and, in Australia, 10%. Much higher percentages are reported from the USA.

The mortality rate of CAP treated in the community is thought to be very low: probably<1%. Mortality among hospitalized patients varies depending on health service but is around 5–10%. Mortality among patients admitted to ICU with CAP is much higher but the statistics are much more varied, again depending on ICU admission criteria. Mortality obviously varies with severity of disease (see the section below on severity assessment) and also with organism. Staph. aureus, Gram-negative bacilli (especially Pseudomonas), Burkholderia pseudomallei and Legionella spp. all carry a higher than baseline mortality while Mycoplasma and the Chlamydophila spp. have lower mortality.

Influenza and pneumonia (ICD codes J10-J18) account for 2.3% of all deaths in Australia and are a contributing cause in 13.3%.

Clinical features

Pneumonia should be suspected in patients with:

Many patients with these features, however, will not have pneumonia and certain groups of patients (particularly the elderly) may have pneumonia with few or none of these features.

A normal chest examination makes pneumonia less likely but does not rule it out. The classically described progression of chest examination findings is from crackles and reduced air entry in the first days, to dull percussion note and bronchial breathing which persists until resolution begins at around day 7–10 when crackles return. Fever is said to be persistent until a ‘crisis’ followed by resolution. The actual clinical reality may bear little resemblance to this. The presence of classical findings in the chest may precede radiological abnormality by several hours, particularly in pneumococcal pneumonia.

Much has been made of the role of the clinical syndrome as a predictor of aetiology but the evidence shows this to be unreliable. Previously ‘typical’ and ‘atypical’ pneumonia have been differentiated clinically but there is now a general consensus that these terms should be abandoned as they are misleading. The term ‘atypical organism’, however, has persisted as an umbrella term for the Chlamydophila spp., the Legionella spp. and Mycoplasma. With these caveats in mind, there are certain associations that should be considered (Table 6.3.1).

Table 6.3.1

Clinical features associated with specific organisms

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Increasing age

High fever

High acuity

Pleurisy

Bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia

Female

Diabetic

Alcoholic

COPD

Dry cough

Legionella

Young and previously healthy patient

Smoker

Multisystem illness (LFT abnormality, elevated CK, GIT upset, neurological disturbance)

More severe illness

Mycoplasma

Young and previously healthy patient

Antibiotic use prior to presenting to hospital

Isolated respiratory illness

Staph. aureus

IVDU

Severe illness

History of influenza

Gram-negative rods

Alcoholic

Nursing home resident

The term ‘community-acquired pneumonia’, as opposed to hospital-acquired pneumonia, is generally defined as pneumonia occurring in a patient who has not been an inpatient in hospital in the last 10 or 14 days. Patients with AIDS, cystic fibrosis, current chemotherapy or active haematological malignancy presenting with pneumonia should be considered to be presenting with a complication of their underlying condition rather than with CAP. The question of how to classify patients with pneumonia presenting from nursing homes remains unresolved. Nursing home status carries an increased mortality risk and an increased risk of both aspiration pneumonitis and of infection with Staph. aureus and aerobic Gram- negative bacilli.

Pathogenesis and aetiology

Most cases of CAP result from aspiration of flora from the upper respiratory tract, although Legionella spp. and Mycobacterium tuberculosis may be aspirated directly in aerosolized droplets suspended in the atmosphere. Haematogenous spread to the lung also occurs, for example from right-sided endocarditis.

Large volume aspiration of gastrointestinal and upper respiratory tract contents is normally prevented by a coordinated swallow and intact gag and cough reflexes; however, microaspiration occurs routinely in normal individuals during sleep. Aspirated matter is generally quickly cleared by the mucocilliary escalator and by periodic coughing.

Pathogens lodging on the lower respiratory mucosa meet with a fine layer of mucus, rich in secreted IgA that acts to prevent their adhesion and to activate other arms of the immune system. These defences may still be breached by the common organisms. Derangement of the defences allows ‘opportunistic’ organisms to cause infection, such as the Gram-negative rods, anaerobes, Staphylococcus and fungi.

Estimates of the rates of occurrence of various organisms implicated in CAP are difficult for several reasons. Isolation of a causative organism occurs in only around 40–70% of cases in hospital-based studies, less so in community-based ones and much less commonly in actual clinical practice (particularly in CAP treated in the community). The most common organism isolated in all settings and in all classes of CAP, Streptococcus pneumoniae (Strep. pneumoniae or pneumococcus), is one of the easiest to isolate whereas Chlamydophila pneumoniae and psitacii (formerly Chlamydia pneumoniae and psittaci) and the Legionella spp. present much greater difficulty, potentially skewing the data in favour of pneumococcus. There is a great deal of heterogeneity in the pneumonia studies with regard to underlying patient characteristics, setting, case definition, degree of diagnostic investigation and timing with relation to epidemics, which further complicates interpretation of the data.

Streptococcus pneumoniae

This encapsulated bacterium has previously been isolated from around 30% of cases of CAP in the community, hospital wards and ICU (50–60% of cases where a cause is found) and more commonly when highly sensitive methods are used for its detection. Recent studies have found lower rates, around 15% (or one-third of cases where a cause is found), which may be due to changing living conditions or pneumococcal vaccination programmes. In about 25% of cases, bacteraemia is identified and, in a few of these, there are other foci of invasive disease (such as meningitis).

Traditionally, this organism has been extremely sensitive to penicillin; however, DRSP is emerging around the world. Sensitivity is generally described by minimum concentration of antibiotic required to inhibit growth in vitro (MIC). MIC<0.1 mg/L represents a sensitive organism, MIC 0.1–1 mg/L represents intermediate sensitivity and MIC≥2 mg/L, higher level resistance. In Australia, approximately 12–20% of isolates express intermediate sensitivity to penicillin but only around 1% have high level resistance. There is considerable local variation in resistance pattern. Invasive strains (isolated from blood or CSF) tend to be more susceptible; 5% are intermediate or highly resistant in Australia. Rates in the UK are lower where less than 3% of pneumococcal bacteraemias are of intermediate or high penicillin resistance while, in Asia, resistance is much more common with 23% of isolates exhibiting intermediate sensitivity and 29% high level resistance, again with marked local variation. Blood levels achieved by giving 1 g amoxycillin orally 8-hourly or 1.2 g benzyl penicillin IV 6-hourly are sufficient to treat the sensitive and intermediate sensitivity strains. In fact, it is only strains with an MIC>4 mg/L that present a significant likelihood of treatment failure at these doses.

Macrolide resistance ranges from 15% in the UK to 92% in Vietnam. Again, invasive strains are less commonly resistant than non-invasive ones.

Multiple drug resistance is a problem with around 17% of Australian isolates demonstrating diminished sensitivity to two or more classes of antibiotic. While respiratory fluoroquinolone resistance remains rare in Australia and the UK, in countries where levofloxacin or moxifloxacin have been more extensively used resistance is already becoming a problem.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

These organisms are not strictly bacteria. They lack a cell wall and so are innately insensitive to beta-lactams but are treated by macrolides, tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones. They are fastidious in vitro and so diagnosis is generally by serological or complement fixation testing. Pneumonia due to Mycoplasma is most common in 5–20 year olds and is rare in the elderly and in the tropical north of Australia. A four-yearly cycle of winter epidemics (with the number of reports varying by a factor of 6–7) is well demonstrated in the UK and surveillance data from Australia suggests that the same phenomenon occurs. Mycoplasma accounts for perhaps 10–15% of cases of CAP. The disease is usually mild and probably self-limiting in adults, although patients with sickle cell disease or cold agglutinin disease are at risk of severe complications.

Legionella species

These aerobic Gram-negative bacilli are fastidious in culture. They occur in sources of lukewarm water, probably hosted by fresh water amoebae and are killed by temperatures above 60°C. Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1, L. pneumophila indeterminate serogroup and L. longbeachiae account for approximately equal shares of legionellosis in Australia. The genus causes a small percentage of cases of mild and moderate CAP (<5%) but is over-represented among severe cases causing 17.8% of cases in UK intensive care units. Outbreaks occur due to contaminated water in air conditioning cooling towers and water supplies and are a significant public health issue. The disease tends to be severe and is often a multisystem illness. Patients on long-term oral steroids are more susceptible but it is less common among the elderly.

Staphylococcus aureus

Staph. aureus, a Gram-positive coccus, is a commensal on the skin and in the oro- and nasopharynx and may reach the lung by aspiration or by haematogenous spread. It is over-represented in severe disease accounting for 25% of ICU pneumonia in the UK and is associated with a high mortality. It is almost universally resistant to penicillin but most cases are sensitive to flucloxacillin and dicloxacillin. CA-MRSA is an emerging problem. Staphylococcal pneumonia classically occurs following influenza and complicates two-thirds of cases of influenza pneumonia in the ICU.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

A comprehensive review of TB pathogenesis and treatment is beyond the scope of this chapter. The classical pattern of disease is for inhalation of the bacillus to lead to a chronic inflammatory reaction, usually in the right lower lobe, producing a walled off granuloma containing surviving organisms and giant macrophages which gradually becomes calcified. At some time in the future, often in the context of immunocompromise due to steroids, malignancy, HIV, malnutrition or old age, the disease reactivates and lobar pneumonia develops (typically in the right upper lobe). The disease is usually subacute in onset and relentless without treatment. The patient often suffers chronic cough, weight loss, fevers and fatigue. That said, TB presents in many and varied ways and a high index of suspicion should be maintained. The patient with pulmonary TB and a productive cough presents a significant infection control and public health risk and respiratory isolation must be initiated while the diagnosis is confirmed.

Other important organisms

Non-typable Haemophilus influenzae is a rare cause of mild CAP and is uncommon in young patients. Although it is associated with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), it is no more common as a cause of CAP in COPD patients than in the general population. It does, however, become more common with increasing severity of pneumonia and increasing age. Less than 25% of isolates are beta-lactamase producing, others are susceptible to aminopenicillins (and somewhat less so, to benzyl-penicillin). Moraxella catarrhalis has similar antibiotic susceptibilities and is less common than Haemophilus. Second-generation cephalosporins, tetracyclines or the combination of amoxycillin and clavulanate is adequate if amoxycillin alone fails.

Chlamydophila (formerly Chlamydia) pneumoniae causes a mild illness and there is some doubt about its role as a pathogen at all. It is sensitive to macrolides and tetracyclines.

Burkholderia pseudomallei occurs in the soil in the tropical north of Australia and in South-East Asia. Infection with it (melioidosis) typically causes a severe pneumonia, although any organ may be affected. Fifty per cent of cases are bacteraemic which is associated with 50% mortality. It makes up 25% of cases of bacteraemic pneumonia in tropical Australia (4% of all pneumonia presentations to hospital and 18% of cases where a cause is found). It is a problem mainly during the monsoon season and risk factors include diabetes mellitus, renal failure, chronic lung disease, alcoholism, long-term steroid use and excess kava intake. It is somewhat sensitive to third-generation cephalosporins, although better treated with ceftazidime or carbapenems. It is intrinsically resistant to aminoglycosides. The Gram-negative rod Acinetobacter baumanii occurs in a similar area, time of year and group of people and also causes severe pneumonia. It is much less common but the case fatality rate is similar. It is generally treated with aminoglycosides. Expert consultation should be sought.

Influenza A and B are common causes of pneumonia in adults. Disease may be mild, moderate or severe. Co-infection with Staph. aureus is a well-described complication. Clinical and radiological differentiation from bacterial pneumonia is unreliable and diagnosis is made usually with viral studies on nasopharyngeal or bronchial aspirates or on serological testing after convalescence.

Anaerobic organisms are generally aspirated in patients with poor dentition. Edentulous patients are thus protected and these organisms are actually rare in aspiration pneumonia among nursing home patients.

The Gram-negative rods are a varied group of opportunistic agents which all carry a high risk of severe pneumonia and mortality. They are more common in nosocomial pneumonia than CAP. They include Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Serratia spp. and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Emergence of antibiotic resistance during treatment is a particular problem with Pseudomonas and antibiotics from two classes should be used concurrently if infection is proven or highly likely.

Associations between particular risk factors and particular organisms in CAP patients are weak and it is important to remember that routine questioning about risk factors is likely to be misleading. For example, despite the well-known association between Chlamydophila psittaci and sick parrots, 80% of patients with psittacosis have no history of bird contact. Stronger associations are those between Staph. aureus and influenza, between Staph. aureus and intravenous drug use (IVDU) and between Legionella and travel. Workers in the animal handling and slaughtering industries are at risk of infection with Coxiella burnetii (Q fever). Awareness of any local epidemics is important, particularly outbreaks of Mycoplasma or legionellosis.

Prevention

Prevention of pneumonia in the first world centres on vaccination for influenza and pneumococcus. In developing regions, the provision of adequate nutrition and housing is more important. Legionellosis is avoided by appropriate design and maintenance of air-conditioning and water supply systems in large buildings.

It is worth noting that aspiration pneumonia is not prevented by the use of nasogastric or PEG feeding tubes.

Differential diagnosis

The clinical syndrome of pneumonia is non-specific and the differential diagnosis is broad. CXR findings of lobar infiltrate, however, narrow the possibilities significantly. Underlying malignancy should always be considered, especially in older patients with a history of smoking. Pulmonary embolus (PE) is less likely in the presence of a lobar infiltrate but this should be differentiated from the wedge-shaped opacification of a pulmonary infarction due to PE. Bi-basal pneumonia can be very difficult to distinguish from left ventricular failure, especially in the elderly patient in whom clinical signs and white cell count can be unreliable. CXR changes may be pre-existing, such as in localized fibrosis from radiotherapy or when there has been a recent pneumonia with opacification yet to resolve. Aspiration pneumonitis should be differentiated from pneumonia as antibiotic therapy is less likely to be of benefit. The main indicators are on history (neurological deficit, loss of consciousness, choking while eating or vomiting in the patient with diminished airway reflexes), although most episodes go unwitnessed.

Complications

Pleural effusion and empyema

Pleural effusion is a fairly common occurrence in hospitalized patients with CAP, occurring in 36–57% of admitted patients. Effusion detectable on CXR is an indicator of severity, especially if bilateral. Persistent fever raises the likelihood of an effusion. The majority of effusions resolve with antibiotic treatment but empyema requires drainage. As effusion and empyema are radiologically indistinguishable, any significant effusion should be aspirated. Cloudy fluid, WCC>100 000/mm3, glucose<2.2 mmol/L, pH<7.2, or organisms on Gram stain indicate empyema and the need for drainage. Aspiration will also provide a specimen for aetiological diagnosis, although the yield is not high.

Abscess

Lung abscess is a rare complication, most common in the alcoholic, debilitated or aspiration pneumonia patient. Some will respond to antibiotics but drainage is often required. Staph. aureus, anaerobes and Gram-negatives are more likely culprits and polymicrobial infection is common. Tuberculosis should be considered in any patient with a cavitating lesion.

Severe sepsis syndromes

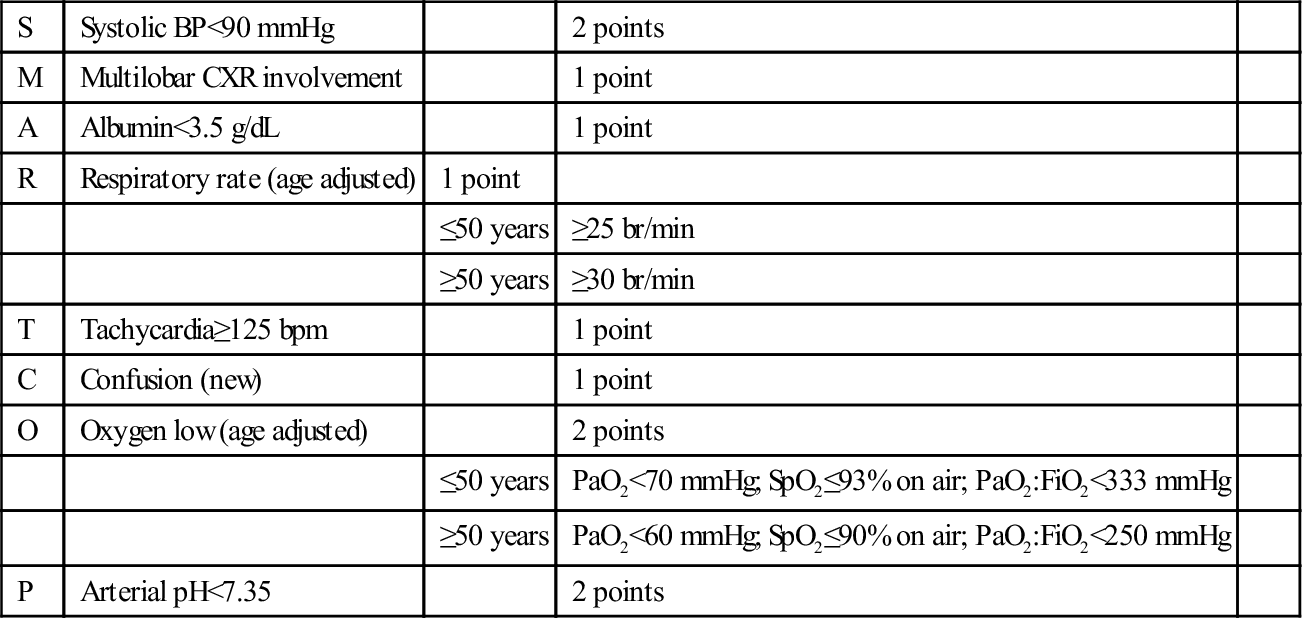

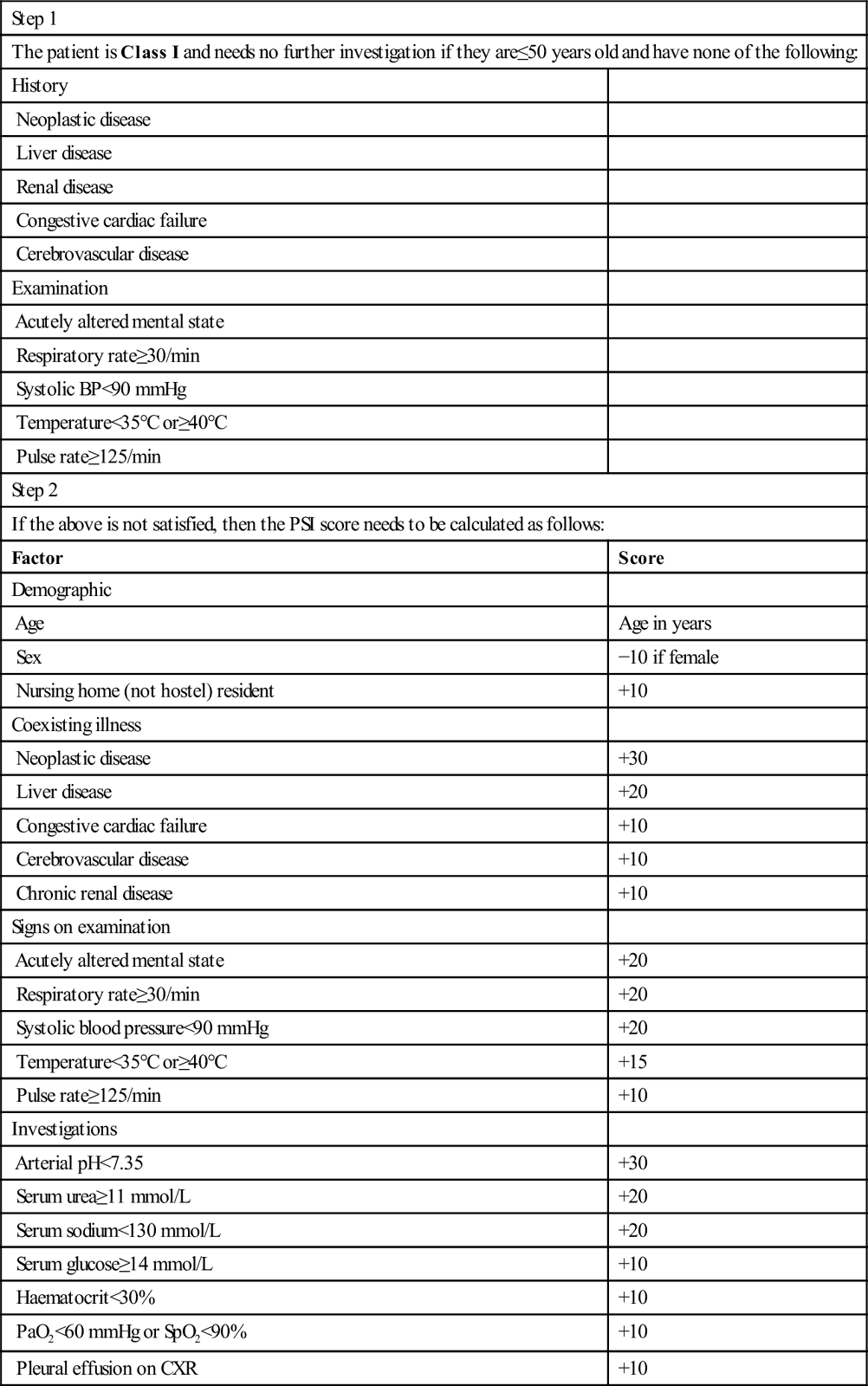

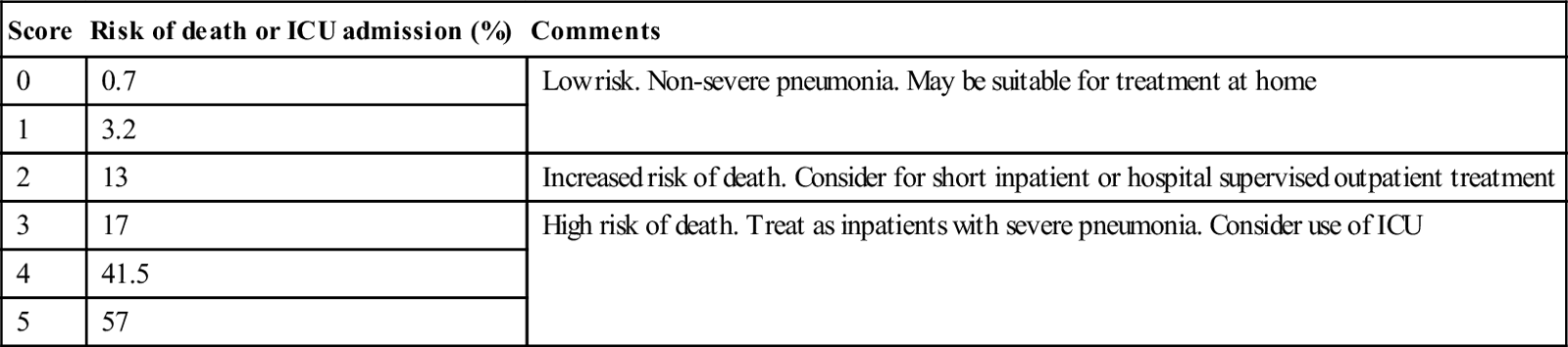

Severe sepsis syndromes are a relatively common occurrence in CAP. Approximately 40% of hospitalized patients develop non-pulmonary organ dysfunction, with 28% having evidence of it at presentation. Septic shock develops in 4–5% of cases and is manifest at presentation in just under half of these. The Pneumonia Severity Index (see below) correlates with the likelihood of severe sepsis and the SMART-COP score (see below) predicts the need for inotropic and respiratory support.

Respiratory failure

Respiratory failure is a common reason for ICU admission in CAP. In patients with moderate to severe disease, a widened A–a gradient can be detected with PCO2 being depressed as the patient increases minute volume to compensate for failure of gas exchange. As severity increases, the PCO2 will return to normal as the patient tires and PO2 will fall. Type II respiratory failure generally occurs late.

Renal failure

Renal failure may occur in any case of severe CAP, but is particularly associated with legionellosis. Multiorgan failure may occur as a result of severe sepsis.

Clinical investigations

Imaging

Chest X-ray

Presence of a new infiltrate on CXR remains central to the diagnosis of pneumonia. Diagnosis without CXR is shown to be unreliable, although a normal chest examination makes the diagnosis unlikely.

CXR has proven to be an unreliable indicator of aetiology, however, some clues may be found. Mycoplasma is less likely in the presence of homogeneous shadowing but is suggested by lymphadenopathy. Multilobar infiltrates and pleural effusions make bacteraemic streptococcal pneumonia more likely, while a multilobar infiltrate with pneumatocoeles, cavitation and pneumothorax is suggestive of Staph. aureus. Klebsiella tends towards the right upper lobe but the described association between this agent and a bulging horizontal fissure is unsupported by evidence.

Tuberculosis should always be considered in cases of upper lobe infiltrate, especially in the presence of a Ghon focus or calcified nodule, usually found in the right lower lobe.

Clues to severity may be found on the CXR (see below).

The role of the repeat CXR is unclear. The rate of improvement is quite variable. It is slower with increasing age, presence of co-morbidity, multilobar infiltrates and Strep. (especially bacteraemic) or Legionella as pathogens. Legionella, in fact, is characterized by worsening radiological appearance after admission. The role of a convalescent film is likewise unclear. Rates of underlying lung cancer vary and most cases are diagnosed on the acute film. Smokers over 50 years of age are particularly at risk and routine convalescent imaging should be considered in this group.

Computed tomography

Computed tomography (CT) currently has a limited role in diagnosis of pneumonia due to cost, radiation dose and lack of a clear benefit over plain CXR. In some cases, a diagnosis may be made on CT when another diagnosis is being excluded (e.g. CTPA for exclusion of pulmonary embolus).

General pathology

The roles of non-microbiological pathological testing in CAP are to help confirm the diagnosis, to assess severity, to identify complications and to screen for underlying or co-morbid conditions. The majority of previously well young people with non-severe pneumonia are unlikely to benefit from routine tests.

Full blood count

The full blood count is routine in the patient requiring hospitalization with pneumonia. Anaemia, thrombocytopaenia, severe leucocytosis and leucopaenia are all markers of severity (see below). Polycythaemia may indicate dehydration or underlying chronic hypoxia. A white cell count over 15 000 cells/mm3 is suggestive of bacterial cause (especially Strep. pneumoniae) but is insensitive and non-specific.

Urea and electrolytes

Urea, electrolytes and creatinine are also routinely measured in the hospitalized patient. Hyponatraemia (Na<130 mmol/L) and elevated urea (≥11 mmol/L) are proven markers of severe pneumonia. Acute renal impairment is a relatively common complication of severe pneumonia, while chronic renal failure is a risk factor for severe disease.

Liver function tests

Liver function tests frequently demonstrate some abnormality, although this may not change management. Chronic liver disease is a risk factor for severe pneumonia. Hypoalbuminaemia is a marker of severity.

Blood gas testing

Measurement of arterial blood gases has been common practice in patients hospitalized with pneumonia. Recent evidence demonstrates that a venous blood gas is acceptable for assessment of acid–base status and may be a valid screening tool for hypercapnoea. Transcutaneous oxygen saturation measurement (SpO2) is, likewise, an acceptable screening tool for hypoxia, although it becomes inaccurate when SpO2 is<90%.

Inflammatory markers

Measurement of C-reactive protein (CRP) remains contentious. The recent British Thoracic Society guidelines update concluded that ‘there is no clear consensus in the literature about value of CRP in differentiating between infective causes. There is no value of CRP in severity assessment’. At best, CRP may have a role in differentiation between exacerbation of COPD and pneumonia or non-infective causes and pneumonia in uncertain cases.

Serum procalcitonin, D-dimer, serum cortisol and other novel biomarkers have been found to correlate with severity of pneumonia but their discriminatory value and role, if any, remain undefined.

Testing for aetiology/microbiology

As discussed above, achieving an aetiological diagnosis in CAP is difficult, even in the research setting in tertiary referral centres.

Advantages of doing so include the opportunity to tailor therapy, to detect outbreaks such as Legionnaire’s disease, influenza or Mycoplasma and to identify resistant organisms. An emerging concern in recent years is that of bioterrorism which may be identified early due to reporting of aetiological diagnoses. A further consideration is the paucity of published data on the aetiology of pneumonia, particularly from Australia and New Zealand. Current knowledge depends heavily upon laboratory reports to surveillance authorities and ‘accumulated knowledge’ rather than scientific studies.

Disadvantages of an aggressive diagnostic approach are the cost compared to the low yield, the risk of inappropriate changes to therapy based on false-positive results from contaminants, the long lag time to get a result (particularly from culture and paired serology), the potential to delay treatment while specimens are obtained and the exposure of the patient to added unpleasant and invasive procedures (such as multiple venepunctures for blood culture). Moreover, it is uncommon for therapy to be streamlined even with microbiological diagnosis. The only randomized controlled trial comparing empiric to directed therapy found no benefit to a pathogen directed approach, although there was a small mortality benefit found in the ICU subgroup.

Sputum

Sputum can be collected for microscopy and for culture. The two should be considered separately as they are very different tests and are likely to be valuable in different settings. The value of sputum collection has been debated, however. Unfortunately, many patients are unable to produce sputum and waiting for them to do so may cause significant delays to antibiotic treatment.

Microscopy (generally with Gram stain, although Zeil-Neilsen stain for acid-fast bacilli should be requested if tuberculosis is suspected) can potentially provide useful guidance for empiric prescribing as well as an indication of whether the specimen is of sufficient quality for culture to be useful.

Sputum culture has a higher sensitivity than Gram stain and provides more definite identification, typing and sensitivity data; however, results are not available when treatment is started and colonization may be hard to distinguish from infection, particularly if Gram stain was negative or not performed. Special culture is indicated if Legionella or M. tuberculosis is to be identified.

Sensitivity of both microscopy and culture decline if antibiotic therapy has already started and, even under ideal conditions, neither is highly sensitive or specific.

Likewise, tuberculosis requires both special stains and culture media as well as prolonged culture time. Provision of good clinical details to the lab including suspected organism, timing of specimen and use of antibiotics is essential.

Blood culture