CHAPTER 6. Patients’ rights to and in health care

L earning objectives

▪ Discuss the relationship between patients’/clients’ rights and moral rights.

▪ Consider the right to health and health care and:

• discuss the right to health

• discuss the right to health care and at least four senses in which it can be claimed

• outline some controversial arguments raised both for and against the right to health care

• explain why an economic framework is morally inadequate for deciding issues of health care justice.

▪ Consider the right to make informed choices and:

• outline the doctrine of informed consent

• explore the notion of the ‘sovereignty of the individual’ and its implications for informed consent practices

• examine critically the five analytical components of informed consent

• discuss critically at least five common objections raised against the right to give an informed consent

• discuss critically the right of competent patients to refuse nursing care.

▪ Examine the notion of competency and its implications for patients with impaired decision-making capacity.

▪ Discuss critically the notion of ‘surrogate decision-making’ in the case of rational incompetence.

▪ Discuss the nature and moral implications of paternalism in nursing and health care.

▪ Consider the right to confidentiality and:

• state the International Council of Nurses’ position on confidentiality

• outline the moral basis and requirements of the principle of confidentiality

• discuss briefly the conditions under which demands to keep information confidential may be justly overridden.

▪ Discuss critically the right to dignity.

▪ Discuss critically the right to be treated with respect.

▪ Discuss critically the right to cultural liberty.

I ntroduction

In 1996, in what has been described by media commentators as ‘the first case of its kind’ in North America, a patient sued his treating physician for ‘keeping him alive’ against his expressed wishes and for not offering him an ‘elective demise’ (Reed 1996: 14). The patient in this case was a 66-year-old man who had been diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a degenerative nerve disorder. Despite having made a ‘living will’ that clearly stated his wishes ‘not to be attached to a respirator’ should his condition deteriorate, the patient was nevertheless placed on an artificial life-support machine when he began experiencing breathing difficulties. As a result of this paternalistic medical decision, he was left totally dependent on 24-hour nursing care, depleted of his life-savings, and deprived of what he regarded as a ‘dignified death’ (Reed 1996: 14). The patient’s life expectancy was estimated at the time of the report to be 5–10 years.

A little over 1 year later, in New Zealand, a case of a very different kind unfolded. In this case, Rau Williams, a 63-year-old Maori man with early stage dementia and suffering a complication of diabetes, was denied kidney dialysis treatment on ‘economic grounds’ (Field 1997: 10). In keeping with national resource allocation guidelines in operation at the time, clinicians concluded that, since Mr Williams was unable to ‘co-operate with active therapy’ (he was unable to perform home dialysis independently), was unable to live independently (even though his family were willing to supervise him), and was not expected to derive more than 1 year of life benefit from dialysis, he was ‘unsuitable for entry on to the [dialysis] program’ (Manning & Paterson 2005: 686–7).

Outraged by the hospital’s decision not to treat their father, and in a desperate bid to secure life-saving treatment for him, Rau William’s family applied to the New Zealand Court of Appeal to intervene. The patient’s evidence was that he did not want to die, and enjoyed some quality of life while on dialysis ‘including pleasure from seeing his family’ (Manning & Paterson 2005: 687). The court determined, however, that the hospital managers ‘did not need to resume kidney dialysis treatment’ (Field 1997: 10). In reaching its decision, the court took the stance that it would be ‘inappropriate for the Court to attempt to direct a doctor as to what treatment should be given to a patient’ (Manning & Paterson 2005: 687). This decision reflected two issues:

first, a recognition that clinical judgment is beyond the expertise of the courts; and secondly, that a court should not make orders with consequences for the utilization of scarce resources since it lacks knowledge of the competing claims to those resources.

(Manning & Paterson 2005: 687)

In response to the case, the then associate Health Minister was reported to have said that ‘health rationing was now a fact of life’. It was subsequently observed that:

Although formal rationing has not previously been acknowledged here [New Zealand], from July every New Zealander referred for surgery in the public health system will be scored for points on clinical and social criteria to determine when they will be treated.

(Field 1997: 10)

Today, in New Zealand, there are no guarantees of access to publicly funded ‘none-core’ health services (Manning & Paterson 2005). Moreover, exclusions from even ‘core treatments’ on the grounds of age and disability are legally justified ‘provided there is an objective, evidential basis to justify [the] exclusions’ (Flood et al 2005: 638; see also Manning & Paterson 2005). The stance taken by New Zealand officials on this issue has earned them a reputation among some international experts as being ‘among the “leading bunch” in the move to explicit rationing’ (Manning & Paterson 2005: 683). Although politicians and health officials prefer to use the term ‘prioritising access’ to health care (rather than ‘rationalising’ or ‘limiting’ access to it), ‘justified discrimination’ in health care has become a poignant reality for New Zealanders (Flood et al 2005: 638; Manning & Paterson 2005).

In 2002, a major Australian newspaper reported on the assault and substandard care of an 87-year-old woman in a state government-run aged care facility (Miller 2002). The report stated that the woman was allegedly assaulted (by another resident) on at least four occasions, found smeared with faeces a number of times, and had had at least six falls resulting in injuries. The woman’s daughter is reported as also alleging that ‘some of the ward emergency buzzers were broken, the toilets were often found in a disgraceful condition’ and that she had seen ‘rats and mice on the ground floor of the aged care centre’ (Miller 2002: 3). The daughter is also reported as stating that ‘for months she complied with the hospital’s internal complaints procedures but abandoned it “when it proved itself to be a futile process” ’ (Miller 2002: 3).

These reports on treating patients against their will, denying patients life-saving treatment for economic reasons, and the provision of substandard care are just some among many examples of patients’ rights violations that can and do occur in health care contexts. Other examples of patients’ rights violations include: breaches of confidentiality, inadequate consent practices, not being treated with respect, and being stigmatised and discriminated against in health injurious and harmful ways. It is to examining patients’ rights and their implications for members of the nursing profession that this and the following chapters now turn.

T he issue of patients’ rights

People requiring or receiving health care are not, and never have been, obliged to be the passive recipients of unnegotiated care. Yet the more we examine the realities of health care practice and the way our health care institutions and services operate, the more apparent it becomes that the rhetoric surrounding the idealism of people’s rights to and in health care does not always match the reality. As the bioethics, legal, professional and lay literature, and our own everyday experience, make plain, people continue to be denied equitable access to both the quantity and quality of health care they need; they continue to be denied the opportunity to make informed choices about their care and treatment options; and they continue to be harmed physically, psychologically, spiritually and morally as a result of morally questionable practices in our health care services and institutions.

Over the past three decades, the issue of patients’ rights has received considerable attention both in Australia and overseas. There exists a vast body of literature on the subject (too numerous to list here), and there has been a proliferation of dramatised accounts of people’s ‘life stories’ on the matter both in books and films. There have also been significant policy and law reforms in the area of patients’ rights, for instance, in relation to:

▪ clarifying people’s common law right to refuse orthodox medical treatment

▪ the lawful appointment of ‘surrogate decision-makers’ (e.g. persons with medical power of attorney) in the case of patients who become incompetent to decide their own medical treatment options

▪ formulating ‘living wills’

▪ the right to an ‘assisted death’

▪ the establishment of clinical ethics committees (CECs) and ‘client support’ persons

▪ the establishment of statutory health services complaints mechanisms

▪ the role of a public advocate in the case of disagreement about treatment decisions

▪ the development of public consumer advocacy groups

▪ the establishment of national ethics committees and commissions.

Despite these important innovations, however, the area of patients’ rights remains problematic.

There is no denying that enormous progress has been made over the past three decades in regard to patients’ rights: violations are monitored more carefully; redress of violations is more substantial; and more effort is now being put into preventing patients’ rights violations from occurring (notably under the rubric of corporate risk/clinical risk management). Nevertheless it is evident that we still have a long way to go in order to ensure that the rights of patients are properly respected and protected in health care domains: dispute remains about who has rights to and in health care; there are disagreements about what rights patients can meaningfully and reasonably claim in certain contexts; there is a lack of certainty about who has corresponding duties to patients’ rights claims; and there is no consensus on how best to resolve disputes in cases where patients’ rights claims compete and conflict — particularly in contexts of diminished health care resources. Important questions remain of: How and what can we learn about the disputes and disagreements that remain concerning patients’ rights? How might we prevent patients’ rights from being violated in the domains in which we work? and How do those who have violated patients’ rights, and the patients whose rights have been violated, come to terms with the aftermath of those violations?

In 1990, the Consumers’ Health Forum (CHF) pointed out that the Australian legal system had not been responsive to protecting the needs of health care consumers. In its report on the Legal Recognition and Protection of the Rights of Health Consumers, CHF states (pp 1–2):

For some consumers the diversity of the Australian legal system has provided some benefits. Unfortunately, for the majority it has been far more effective in creating an inequitable and unresponsive legal maze. As it currently stands:

– there is no clear direction for consumers as to how they should act, how others should act, and what redress they have if things go wrong (their rights depend upon which State consumers live in or even whether they attend a public or private health facility); and

– the interests of bureaucrats and professional groups are better reflected in existing law than the interests of consumers and the community in such matters as information, participation, accountability and openness.

At the time of writing, these issues remain in need of attention. Although health law and ‘therapeutic jurisprudence’ are being increasingly recognised as a foremost area of legal practice, discourse and research in Australia, questions remain ‘about the legitimacy and coherence of health law’ and its ultimate impact on the health interests of individual consumers and communities alike (Freckelton & Petersen 2006: 3). In the case of the legitimating individual and community health as a fundamental objective, for instance, Australian courts, like their overseas counterparts, are generally reluctant to affirm a positive right to health care (Flood et al 2005). Although human rights discourse in Australian law is gaining increasing importance ‘in relation to matters of life, death and health’ (Freckelton 2006), its commitment to affirming consumers’ positive right to health care is at best dubious.

It can be seen then that the issue of patients’ (clients’) rights is of obvious importance to the nursing profession. If nurses are to respond effectively to this issue, however, they need to have knowledge and understanding of, first, what patients’ rights are, and second, how these rights can best be upheld. It is to advancing an understanding of these matters that this discussion will now turn.

W hat are patients’ rights?

To put it simply, patients’ or clients’ rights are a subcategory of human rights. Statements of patients’ or clients’ rights are merely statements about particular moral interests that a person might have in health care contexts and that require special protection when a person assumes the role of a patient or client. Referring to this particular set of interests in terms of ‘patients’ rights’ or ‘clients’ rights’ serves more the purposes of manageability than those of philosophy. For example, when the notion patients’ rights or clients’ rights is used, we know immediately what kind of context and what kind of rights claims are likely to be encountered. The notion of patients’ rights or clients’ rights in this instance immediately ‘sets the scene’, or identifies the domain of concern. In the case of human rights language, the scene that is set is much broader. Some might consider human rights language in health care contexts to be somewhat cumbersome to manage. This is not to say that it would be inappropriate to use the notion of human rights in health care contexts; quite the reverse. In many respects, using human rights language might be more compelling and more effective in drawing attention to and commanding respect of the deserving moral interests of people in health care domains.

It is perhaps important to clarify that patients’ rights statements tend to include a mixture of civil rights, legal rights and moral rights. Popular examples of patients’ rights include: a right to health care, a right to be informed, a right to participate in decision-making concerning treatment and care, a right to give an informed consent, a right to refuse consent, a right to have access to a qualified health interpreter, a right to know the name, status and practice experience of attending health professionals, a right to a second medical opinion, a right to be treated with respect, a right to confidentiality, a right to bodily integrity, a right to the maintenance of dignity, and many others. Many of these rights statements derive from the broader moral principles of autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence and justice, already discussed in this book. Unfortunately there is insufficient space here to discuss every type of patients’ right that has been formulated at some time or another. For the purposes of this discussion, attention is given to only six broad categories of rights, under which many other narrower rights claims fall. These category claims include the rights to health and health care, to make self-determining choices (informed consent), to confidentiality, to be treated with dignity, to be treated with respect and to cultural liberty.

T he right to health and health care

In keeping with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, all people have a right to health. The World Health Organization (WHO 2002a) has clarified that the right to health does not entail the right to be healthy, but the right to the highest attainable standard of health, as articulated in General Comment 14 of article 12 of the United Nations’ International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (United Nations CESCR 2000). This, in turn, has been interpreted as requiring governments and public authorities to ‘put in place policies and action plans which will lead to available and accessible health care for all in the shortest possible time’ (WHO 2002a: 9).

The right to health and health care is complex and controversial. As well as being a sensitive moral issue, it is also a highly charged political issue, as ongoing debates on population health and health care resource allocation make plain (see, e.g. Daniels 2006; Dyck 2005; Powers & Faden 2006).

Bioethicists have yet to find a happy medium between the many competing and conflicting views on the subject. Some philosophers argue that health and health care is something all people are equally entitled to, regardless of the cost. Where human life is at stake, they contend, decisions about health and health care should not be constrained by economic considerations (Brody 1986; Powers & Faden 2006). Moreover, in keeping with what is known as the ‘rescue principle’ which imposes a duty on individuals and communities to ‘save and rescue human life’ and to ‘prevent and avoid illness, injuries, and violations of human rights generally’ (Dyck 2005: 280), it is ‘intolerable when a society allows people to die who could have been saved by spending more money on health care’ (Beauchamp & Childress 2001: 246). If more money is required, the solution is relatively simple: redirect society’s resources — for example, away from gross expenditures on arsenals of arms and other life-threatening instruments of war; and towards improving health promotion and illness-injury prevention programs and towards redressing existing inefficiencies in the system (Dyck 2005: 317–21). In addition, attention should be given to containing costs of needed medical care by containing the risks of medical malpractice litigation and the related high costs of insurance premiums that are being built into and hence adding to the costs of medical services (Dyck 2005: 317–18).

Others argue that it is implausible and impossible to ensure ‘good health’ and to provide a high standard of health care to all persons equally. In the case of health care, at best, all that people can reasonably claim is a ‘decent minimum’ of health care, as measured in terms of the amount necessary to secure a minimally decent or ‘tolerable’ life (Sreenivasan 2007; Engelhardt 1986: 336; Buchanan 1984; Fried 1982). Some theorists further argue that having access to only a ‘decent minimum’ of health care is particularly compelling when it is considered that, since social determinants are a more reliable precursor of health — and that having universal access to health care as such does not necessarily ensure health — the assumed ‘equal right to a high standard of health care’ is not only unsustainable, but lacks sound moral justification (Sreenivasan 2007). Still others argue that there is no such thing as a right to health care. One philosopher even claims that it is immoral to speak of health care as a ‘right’ (Sade 1983), and another that the expression ‘a right to health care’ is nothing but a ‘dangerous slogan’ (Fried 1982).

Charles Fried (1982: 400) claims that the ‘impossible dilemma posed by the promise of a right to health care’ is really nothing more than a product of ‘our culture’s inability to face and cope with the persistent facts of illness, old age, and death’. He goes on to assert provocatively that (p 400):

Because we are little able to come to terms with the hazards which illness proposes, because the old are a burden and an embarrassment, because we pretend that death does not exist, we employ elaborate ruses to put these things out of the ambit of our ordinary lives.

Whether the right to health and health care is a bogus claim or a dangerous slogan or a cultural quirk will, however, depend very much on how the notions of ‘health’ and ‘health care’ are interpreted. There is room to suggest that criticism of the right to health care derives from the erroneous equation of ‘health care’ with ‘medical care’. Since medical care makes up only a small proportion of overall health care, it is obviously not synonymous with health care. Moreover, as the vast body of literature on the social determinants of health make plain, even if medical care was the major form of health care, it would not necessarily guarantee ‘good health’ (Wilkinson & Marmot 2003; Sreenivasan 2007). Once the notions of ‘health’ and ‘health care’ are understood in more holistic terms, the right to these things may not seem so outrageous or fraudulent or even culturally odd as a claim. Every culture has its way of promoting health and preventing ill-health, of dealing with sickness, illness, pain and suffering, and of caring for the ill and injured. However, not every culture embraces Western scientific medicine as the most effective way of dealing with health, sickness and related illness experiences. And thus not every culture is posed with the dilemma of economic restrictions on resource allocation. Once health and health care, in their more holistic and socially determined sense, are seen as an important means of promoting a person’s total (and not merely physical) wellbeing, it becomes increasingly difficult to deny that claims to it are valid and morally justified.

What makes a claim to health and health care compelling is precisely that, once it is accepted, it has the moral power to prescribe actions to relieve the distressing symptoms caused by illness and injuries, to promote human wellbeing (a moral end) and, indeed, to promote human life itself (also a moral end) (Powers & Faden 2006; see also Dyck 2005, Chapter 11‘Justice and nurture: rescue and health care as rights and responsibilities’). If we deny entitlements to health and health care, we must also deny entitlements to a range of other interests, including those of life, happiness and even the exercise of self-determining choices.

It is beyond the scope of this text to deal with the many arguments and counter-arguments raised in response to the question of whether people have a right to health and health care. What is of concern here is to clarify the nature of the claim to a right to health and health care, and what might be meant by such a claim.

People’s entitlement to receive health and health care first received global recognition with the signing of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights on 10 December 1948. Article 25 states:

Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and wellbeing of himself [sic] and his [sic] family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his [sic] control.

(United Nations 1978: 8)

It is worth noting here that the right to health and health care embodied by this statement extends far beyond a claim of mere medical care, and embraces a more holistic and socially determined interpretation of health and health care.

Since the signing of this declaration the question of the right to health and health care has taken on a new meaning, and has emerged largely as a result of what people perceive to be an ‘unjust or unfair state of affairs’ involving present structures of health and social care, which are seen as diminishing and even eliminating possibilities for the enhancement of the quality of human life and for human life itself (Powers & Faden 2006; Teays & Purdy 2001; McCullough 1983).

In speaking of the more specific right to health care, it is important to distinguish at least four different senses in which it can be claimed: that is, the right to equal access to health care; the right to have access to appropriate care; the right to quality care; and the right to safe care.

The right to equal access to health care

Access to health care refers to ‘whether people who are — or should be — entitled to health care services receive them’ (Emanuel 2000: 8). The right to equal access to health care raises questions of distributive justice and of how the benefits and burdens associated with health care service delivery ought to be distributed. It also raises questions of whether people or institutions can be found morally negligent for failing to provide equal access to health care for persons requiring it. Responses refuting this sense of a right to health care typically centre on such arguments as: ‘there is not a “bottomless pit” of health care resources, and somebody has to do without’.

Specifically, the ‘scarce resources, but unlimited wants’ argument tends to be constructed as follows:

1. the demand for health care has outstripped supply

2. this is fundamentally because health care resources are limited

3. different people have different health needs, and different views on how existing resources should be used to meet these needs

4. it is true that existing health care resources can be used in alternative ways

5. nevertheless, health care resources are limited, so it is not possible to satisfy everybody’s needs and wants (Beauchamp & Childress 2001; Dyck 2005; Teays & Purdy 2001).

The ultimate conclusion drawn from these premises — the ‘bottom line’, so to speak — is that, inevitably, choices will have to be made. In particular, borrowing from Sheehan and Wells (1985: 59), choices will have to be made about:

1. the conditions for which scarce resources should be made available

2. the priority with which given conditions should be treated.

It remains an open question, however, whether we have to accept the premises of this ‘scarce resources, but unlimited wants’ argument and, further, whether we have to accept its apparent ‘inevitable’ conclusions. It is far from clear that we do have to accept them — particularly when the politics of health and health care resource allocation are considered fully, including the vested and powerful interests that the whole health and health care economics debate is serving. Further, it is also open to serious question whether we are obliged to accept that economic principles ought to supplant morality as the ultimate test of conduct, as an economic rationalisation approach to health care dictates. Human life is not something that can be reduced, like an object, to mere economic worth, and as moral beings we ought to resist attempts to do so; if we do not resist, we risk seeing ‘worthless’ human beings (increasingly characterised as ‘unproductive burdens on society’) denied the health care entitlements they would otherwise be entitled morally to receive.

It is important to recognise that the issue of resource allocation goes far beyond the simple question of merely how to allocate dollars and cents. It involves much broader questions of how to measure quality of life, efficacy of health care and medical treatment, and quality of care, and of how to calculate cost-effectiveness, as well as complex socio-cultural questions pertaining to power, politics and profit (see David Lindorff’s controversial and provocative text Marketplace medicine: the rise of the for-profit hospital chains [1992]). Fundamentally, it also involves questions of how best to promote health, not merely access to health care services in ‘bricks and mortar’ hospitals (Faden & Powers 2006; Johnstone 2002b; Teays & Purdy 2001; Emanuel 2000).

Unless nurses address these other broader questions — both academically and professionally — they will never be in a position to offer a convincing account of why health care (whatever form this may take), not merely hospital or medical care, needs to be better recognised and why it must be more appropriately resourced. A strong stand must be taken on the need to recognise and to fund the promotion of health better (not just health care services), and there is considerable scope to suggest that it would be appropriate for the nursing profession to lead such a stand (see also Christensen et al 2001). More than this, the nursing profession has a moral obligation to lobby effectively for the community as a whole, and the individuals who comprise it, to have better access to the processes that promote health, not merely to hospital or medical care and related services (Johnstone 2002b; Christensen et al 2001).

The right to have access to appropriate care

The right to have access to appropriate care is a second sense in which a right to health care can be claimed. This sense raises important questions concerning the cultural competency and cultural safety of care (see Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS] 2001a, 2001b; Johnstone & Kanitsaki 2007a, 2007b; Papadopoulos 2006) as well as its ability generally to accommodate people’s personal preferences, health beliefs, health values and health practices. As examples given in Chapter 4 of this book have already shown, failing to provide health care in a culturally appropriate, responsive and informed manner can have harmful consequences (clinically, legally and morally) (see also Johnstone & Kanitsaki 2006b; Smedley et al 2003). Other examples given throughout this book will lend further weight to claims that failure to provide people with access to appropriate care can result in otherwise preventable adverse outcomes for both patients and health service providers alike.

Many other examples can be given here. The complementary therapy movement, for instance, has posed all sorts of new dilemmas for the scientific health professional, particularly in instances where patients prefer to try scientifically ‘ unproven’ vitamin or herbal remedies, meditation and other ‘alternative’ therapeutic agents for serious diseases, rather than risk the known and unpleasant side effects of more orthodox medical treatments. To some extent this type of problem has been overcome on account of alternative therapies being better researched, and more widely accepted by health professionals. Today, it is not uncommon for patients to receive a combination of orthodox and unorthodox treatments (e.g. performing surgery as well as administering vitamin and herbal therapies, or administering orthodox drugs as well as performing spinal manipulation, acupuncture and acupressure, facilitating meditation, and the like).

Another aspect of ‘appropriate care’ entails patients having access to people (lay folk and professional) of their own choosing. It also includes patients’ entitlements to seek a second medical opinion, to refuse a recommended medical therapy or folk therapy, to choose an alternative health therapy, to be surrounded by family and friends, to have unrestricted visiting rights, and to decline to be ‘ordered’ to do anything they do not wish to do (including getting out of bed, having a shower every day, and taking prescribed medication). As the Australian Consumers’ Association (1988: 16) pointed out long ago, patients do not need a doctor’s or nurse’s ‘permission’ (to be distinguished here from advice) for anything!

If nurses are to respond to this sense of a right to health and health care, they need to gain knowledge and understanding of their patients’ health beliefs and health practices and to negotiate ways in which these can be accommodated and met appropriately.

The right to quality care

A right to quality care is the third sense in which the right to health care can be claimed. This sense raises questions concerning the accountability, responsibility and competency of health professionals and health care providers, and about the standard of care that is actually delivered. Not only are practical and technical skills at issue here, but also attitudinal factors such as a health care provider’s attitude towards patients as human beings with needs and interests, who are entitled to participate in decision-making concerning their care. A claim to receive quality care also raises questions concerning what should be done in the case of the ‘impaired professional’— that is, someone who functions below an otherwise acceptable professional standard.

Quality health care as a right is an ambiguous and complex notion. Nevertheless, an attempt must be made to understand and use it in a meaningful way. This can be achieved by appealing to the agreed standards of the profession, experience, commonsense (e.g. concerning the distinctions that can be readily made between ‘quality care’ and ‘substandard care’), formal quality assurance processes, formal measures of patient outcomes, and the like. The task for the nursing profession is to ensure that health care delivery never falls to a level that compromises patient safety and wellbeing; nurses in many parts of the world have already demonstrated their willingness to ‘blow the whistle’ or to take strike action when patient safety is compromised by substandard conditions and resources (some examples of which will be considered in Chapter 13 of this book).

The right to safe care

It is generally accepted that all people receiving health care have the right to be safe (Kohn et al 2000; Sharpe 2004). This right has been interpreted to mean ‘the right to be kept free of danger or risk of injury while in health care domains’, which in turn has been further interpreted as entailing ‘a correlative duty on the part of health service providers to ensure that people who are receiving care are kept free of danger or risk of injury while receiving that care’ (Johnstone & Kanitsaki 2007c: 186; see also Johnstone 2007a, 2007b). These moral requirements are unremarkable in that they ‘reflect the well-established principle in health care of “do no harm” and the associated moral duty on the part of health care providers to avoid commissions and omissions that could otherwise result in preventable harm to patients’ (Johnstone 2007b: 82). Underpinning this stance is the universal recognition that ‘people generally have a special interest in their significant moral interests (e.g. to life, quality of life, dignity, respect) in not being harmed and that this special interest ought to be protected — provided this can be done without sacrificing other significant moral interests’ (Johnstone 2007b: 82).

The International Council of Nurses (ICN) regards patient safety as being ‘fundamental to quality health and nursing care’ and asserts that all nurses have a fundamental responsibility to ‘address patient safety in all aspects of care’, including (but not limited to) ‘informing patients and others about risk and risk reduction’, ‘advocating for patient safety’ and ‘reporting adverse events to an appropriate authority promptly’ (ICN 2002: 1). In keeping with the principles of a ‘system approach’ to human error management, the ICN explains:

Early identification of risk is key to preventing patient injuries, and depends on maintaining a culture of trust, honesty, integrity, and open communication among patients and providers in the health care system. ICN strongly supports a system-wide approach, based on a philosophy of transparency and reporting — not on blaming and shaming the individual care provider — and incorporating measures that address human and system factors in adverse events.

(ICN 2002: 1)

A noteworthy feature of the right to safe care is the impetus it is providing, via its encompassment in the new patient safety movement, for the development of a non-punitive systems approach to human error management in health care and to reducing the incidence and impact of preventable adverse events in patient care domains. Although the global push to improve patient safety is not without various tensions and controversies (see Johnstone 2007a, 2007b; Johnstone & Kanitsaki 2006a, 2007d; Sharpe 2004), it is unequivocally heralding a new global understanding, commitment and approach to the historical maxim of ‘do no harm’ and to designing and implementing better systems for reducing the incidence and impact of preventable adverse events and the harms that can and do result from these to all concerned (WHO 2005a, 2005b, 2006).

Challenges posed by the right to health care

It can be seen that all four senses of the right to health care pose a significant challenge to the nursing profession. As far as the right to equal access is concerned, nurses have much to contribute. Nurses know very well the areas in which access to health care has effectively been denied to people, and why (e.g. lack of appropriate resource allocation, inappropriate structuring of health care delivery, obstructive institutional policies and legal laws, cultural and language barriers). Despite their knowledge and experience in relation to these matters, however, nurses are not always included in the processes for deciding important policy or health resource allocation matters.

Nurses must directly participate in high-level decision-making concerning health care matters, an imperative already well argued for by Paul Gross (1985) over two decades ago. If nurses fail to influence policy and decision-making, the prospects for patients’ rights, not to mention the nursing profession’s ability to promote and protect these, will remain limited.

The right to health care, in the senses pertaining to appropriate, quality and safe health care, also poses significant challenges to the nursing profession, in terms not only of its own standards, but also of those applied in health care contexts generally. If the nursing profession is to succeed in providing appropriate nursing care (a subcategory of health care), it needs to pay careful and continuous attention to developing its curricula and to ensuring that its members are educationally prepared to meet and to respond to the needs of society, and in particular the needs of the culturally and individually diverse people comprising it. As well as this, the nursing profession must pay careful attention to developing reliable mechanisms for guiding its members in their attempts to deliver safe, quality, therapeutically effective, culturally competent and morally accountable care, and for censuring those of its members who fail to do so.

Nurses, individually and collectively, have a moral responsibility to respond to the demonstrable threats that are mounting against people’s rights to health and health care. How well they can and will succeed in fulfilling this responsibility, however, will depend on how they view justice and the demands it places on them. As Dyck (2005: 322) reminds us, ‘In the end, health care is one of the areas that test whether members of the community in question are aware of, and willing to meet, the moral demands of the moral requisites of community.’ Moreover, in the context of claims to a ‘decent minimum of health care’:

To ask what justice demands of us, to ask what we owe one another, is to ask what kind of community we aspire to be in our relations to one another, particularly when some among us are ill and otherwise in need. What we do about health care reflects what kind of community we are, and what we think ought to be done about health care reflects what kind of community we think we ought to be.

(Dyck 2005: 307–8)

Meanwhile, what we as nurses do about health care reflects what kind of profession we are, and what we think ought to be done about health care reflects what kind of profession we think we ought to be.

T he right to make informed decisions

The right of people (including ‘mature minors’ and the very old) to make informed decisions and to formally consent (or refuse to consent) to treatment in health care contexts is now widely recognised as a ‘basic ethical and legal precondition to conscientious medical practice’ and the conscientious provision of nursing care (Dickens & Cook 2004: 309; see also Alderson et al 2006; Derish & Vanden Heuvel 2000; Dickens & Cook 2005; Dudzinski & Shannon 2006a, 2006b; Forrester & Griffiths 2005; Kerridge et al 2005). Of all the patients’ rights which might be claimed in a given health care context, however, none is perhaps more challenging to the power, authority and sometimes the integrity of attending health professionals than the patient’s right to make informed choices about his or her care and treatment. This might help to explain why, despite the apparent success of the patients’ rights movement over the past few decades, the right of patients to give an informed consent to care and treatment continues to be problematic in some areas. For example, over the past 20 years I have conducted numerous workshops and seminars addressing ethical issues in nursing. Disturbingly, nurses attending these educational activities have consistently identified the following problems in relation to consent to treatment practices:

▪ patients signing consent forms without having any comprehension of what it is they are consenting to

▪ nurses assuming incorrectly that treating doctors have explained a recommended medical procedure or treatment to a patient/relatives before obtaining the patient’s consent

▪ relatives/chosen carers being upset at discovering that a recommended medical procedure had not been properly explained to a loved one before being performed

▪ signed consent forms being treated as generic; that is, as signifying a consent to ‘anything deemed necessary’ during the period of hospitalisation

▪ patients giving consent to a particular procedure being performed, only to discover later that a different procedure was performed without any ‘real choice’ being given (e.g. the patient may have consented to having laparoscopic surgery only; upon recovery, however, he or she finds that a more radical open surgical procedure has been performed)

▪ verbal consents being obtained from relatives/chosen carers over the telephone in situations which are not of a true ‘emergency’ nature (e.g. where there has been a last-minute cancellation from a private list and a bed has become vacant for a new elective surgery patient)

▪ consents being obtained from people of non-English-speaking backgrounds without the assistance of qualified health interpreters

▪ patients consenting to a procedure, knowing what the procedure involves, but having no knowledge of associated risks or potential adverse side effects of the procedure in question

▪ consent being obtained from patients after they have received a pre-medication or when they are under the influence of alcohol or other mind-altering drugs

▪ procedures performed without consent being obtained from the patient at all.

In disclosing these problems, the nurses have also expressed considerable distress at what they see as their inability ‘to do anything about the problem’.

The issue of informed consent has obvious implications for nurses, not least on account of them being at the forefront of receiving requests from patients and relatives for ‘information’. As well, nurses are at the forefront of being expected to take appropriate action when patients’ information needs are not being met and/or when their (the patients’) entitlements in regard to consent practices are unjustly violated. It is therefore important that nurses have a thorough understanding of the nature and function of informed consent, as well as their responsibilities as nurses in relation to facilitating a patient making informed choices about recommended care and treatment options and as are specified in their respective codes of ethics and conduct (see Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council [ANMC] 2008a, 2008b; ICN 2006). It is to exploring these two issues that this discussion will now turn.

What is informed consent?

The doctrine of informed consent, although having a profound ethical dimension, is essentially a legal doctrine developed partially out of recognition of the patient’s right to self-determination and partially out of the doctor’s duty to give the patient ‘information about proposed treatment so as to provide him or her with the opportunity of making an “informed” or “rational” choice as to whether to undergo the treatment’ (Robertson 1981: 102; see also Beauchamp & Childress 2001; Gert et al 1997; Kerridge et al 2005).

In distinguishing the differences between a legal and a moral approach to informed consent, Faden and Beauchamp (1986) explain that the legal law’s approach to informed consent ‘springs from pragmatic theory’, which focuses more on a doctor’s duty to disclose information to patients and not to injure them. By contrast, moral philosophy’s approach to informed consent ‘springs from a principle of respect for autonomy that focuses on the patient or subject, who has a right to make an autonomous choice’ (p 4).

Whether such a clear-cut distinction can be drawn between a legal and a moral approach to informed consent is a matter of some controversy, however. The moral demand to respect autonomy is clearly the prime motivator of the doctor’s duty to disclose information, and the moral principle of non-maleficence is the prime motivator of the doctor’s duty not to injure or harm patients. It seems that, while the moral and legal approaches to informed consent can be loosely distinguished, they are nevertheless inextricably linked. It is this linkage which highlights the other important functions, besides the promotion of patient autonomy, that the application of the doctrine of informed consent also serves, namely those of protecting patients, avoiding fraud and duress (i.e. as occurs when information is not disclosed), of encouraging self-scrutiny by health professionals, of promoting ‘rational’ and systematic moral decision-making, and of involving the public ‘in promoting autonomy as a general social value and in controlling biomedical research’ (Capron 1974; Gert et al 1997; Beauchamp & Childress 2001).

There is no question that consent practices have improved considerably over recent decades. Health professionals have increasingly recognised the benefits of ensuring that patients (and their proxies) are informed appropriately about their care and treatment options, and patients (and their proxies) are more willing to question the information that they have been provided in order to inform their choices and consent to treatment (Chaboyer 2000; Kerridge et al 2005; Tweeddale 2002). Nevertheless nurses continue to witness instances in which consent practices have been questionable and where patients’ rights to make informed choices have been violated. Patients who do not speak or read English proficiently are particularly vulnerable in this regard, as illustrated by the following case of a 66-year-old Greek-born woman (‘Mrs G’) who had been admitted to hospital for elective surgery to treat a kidney disorder (Kanitsaki 1992). In this case informed consent was not obtained. Describing the circumstances surrounding the failure to obtain an informed consent from this woman, Kanitsaki writes (1992: 2–3):

The morning of Mrs G’s operation arrived, and it was observed by the nurse who was to prepare her for theatre, that Mrs G’s consent form was not signed. The nurse reported this to the charge nurse who rang the relevant doctor to come and obtain Mrs G’s signature on the consent form. The surgical registrar arrived, and in an irritable tone asked ‘why this was not done the day before’. The nurse remarked that Mrs G only spoke a few words of English, and would need an interpreter to explain to her what she was signing and why. The doctor replied ‘I know. But I have no time to wait. It will be alright’. He then proceeded to instruct Mrs G how to sign the consent form. Mrs G sat up in bed, however, and looking puzzled, uttered ‘Me no understand. Me no understand.’ The doctor then proceeded to pick up Mrs G’s hand, placed a pen into it, and by holding and directing her hand, made a cross on the consent form. Once this was achieved, the doctor gently touched Mrs G’s hand and said ‘Good. Good.’ He then left the ward.

More recently a 2005 Australian study has suggested that, in some situations, because of not having access to qualified health interpreters, doctors sometimes rely on diagnostic testing (often subjecting patients to an unnecessary barrage of expensive diagnostic investigations) rather than direct diagnostic questioning of patients to find out what might be wrong with them. Consent practices in these situations were, at best, ‘dubious’. The study found that a testing rather than a communicative questioning approach to medical care was most likely to occur in situations where attending health professionals took the stance of treating patients ‘as if’ they were unconscious — sometimes referred to colloquially as ‘veterinary medicine’ (Johnstone & Kanitsaki 2005: 152).

One reason why consent practices in Australia and New Zealand are problematic relates to the model they are based on. Unlike the United States (US) and Canada, which use a reasonable patient standard (also called ‘reasonable person standard of disclosure’) model of consent (emphasising trespass and battery), Australia and New Zealand tend to use a reasonable doctor standard (also called ‘professional practice standard of disclosure’) model (emphasising negligence and malpractice) — although, following the High Court of Australia case of Rogers v Whittaker (1992), Australia has moved somewhere between the two, adopting a ‘subjective person standard’ (emphasising a ‘duty to disclose’ information that an individual patient may require (Kerridge et al 2005: 217–18; see also Russell 1987: 18). Understanding the difference between these three models is important to any debate on informed consent, and I will briefly outline them here. (For a more detailed discussion on the legal aspects of informed consent to medical treatment, see Andrews 1985; Dickens & Cook 2004; Faden & Beauchamp 1986; Forrester & Griffiths 2005; Kerridge et al 2005; Kirby 1995; Law Reform Commission of Victoria et al 1987).

In the reasonable doctor standard model of consent, a consensus of reasonable and established medical opinion provides the ‘objective’ measure. On the basis of this model, a doctor has the duty to use reasonable skill and may withhold information if, in the doctor’s opinion, its disclosure would be injurious to the patient. If patients are to successfully sue for damages on account of a failure to disclose information relevant to the consent process, they have to show, first, that the doctor failed to provide information and advice to a patient that accords with the ‘practice existing in the medical profession’ (Law Reform Commission of Victoria et al 1987: 8), and, second, that injury was suffered as a (causally) direct result of this negligence. In establishing whether the doctor did in fact use ‘reasonable skill’, the law would appeal to the reasonable doctor standard model and would ask what most or many reasonable and competent doctors in a given particular branch of medicine would do and say in such circumstances; that is, what would be considered ‘accepted medical practice’ in this situation? If there were conflict, the answer to this question would be sought from an expert medical witness, or witnesses, who would testify what they, as reasonable and competent doctors in a particular branch of medicine, would probably do or say in the circumstances under question.

For example, the question of whether a doctor should have disclosed to a patient a 0.1–0.2% risk of quadriplegia in cases involving cervical spinal surgery would ultimately be decided on the basis of whether other reasonable and competent doctors in the field usually disclose this information. If it could be established that other reasonable doctors do not disclose to their patients a 0.1–0.2% risk of quadriplegia in cases involving cervical spinal surgery, it is likely that a doctor who failed to disclose such information to a patient would not be found negligent or causally responsible for the patient’s injuries in the case of a material risk manifesting itself (such as quadriplegia).

In the reasonable patient standard model, on the other hand, the standard is set ‘by reference to hypothetical behaviour of adult, competent people in the sorts of situations which are presented to courts and other tribunals for decision’ (Law Reform Commission of Victoria et al 1987: 8). On the basis of this model, a doctor has the duty to disclose to the patient all the information necessary to making an intelligent and ‘rational’ choice (including information pertaining to small material risks). For example, consider the hypothetical case of a patient who has suffered the complication of quadriplegia following a cervical spinal fusion. Consider further that the patient claims that, had information been given about the associated risk of quadriplegia, the operation would never have been consented to in the first place. The famous Sidaway case provides an instructive example of this kind of situation (Law Reform Commission of Victoria et al 1987: 3–4, 37–9; Andrews 1985: 14). In the hypothetical case, the question of whether a doctor should have disclosed to the patient a 0.1–0.2% risk of quadriplegia in cases involving cervical spinal surgery would ultimately be decided on the basis of whether:

1. the information that was withheld was critical to the patient’s making an intelligent choice

2. the information would have caused the patient to make a different choice had she or he been informed of the associated risks before giving consent

3. the patient’s desire to know of the given associated material risks was consistent with the desires of a hypothetical reasonable and competent adult

4. the risk was considered to be severe (i.e. the injury, were it to occur, would be of a serious nature; quadriplegia in this instance is clearly ‘severe’ viz ‘of a serious nature’)

5. the probability of the risk occurring was high.

If it could be established, in this instance, that the patient would not have consented to the procedure, and that the patient’s declining to give consent would have been consistent with what a hypothetical reasonable and competent adult would do in a similar situation, then the patient’s original consent would be vitiated and the doctor would be found guilty of trespass and battery.

In the subjective person model, the standard is based on the requirement to tell ‘each individual patient exactly what they would wish to know’ [emphasis original] (Kerridge et al 2005: 218). According to this standard:

If a patient wants or would need certain information in order to make an informed decision that is congruent with her or her life-goals, then non-disclosure of such information may infringe upon personal autonomy.

(Kerridge et al 2005: 218)

The influence of this standard has been most evident in the High Court of Australia case of Rogers v Whittaker (1992), involving a 47-year-old woman who developed sympathetic opthalmia and who became completely blind after undergoing reparative eye surgery for a penetrating eye injury. This case is widely credited with representing the Australian position ‘not only in relation to the standards of the duty of care for health professionals, but also in relation to “whether the standards of care is a matter of medical judgment only”’ (Forrester & Griffiths 2005: 96). Evidence was given at the court hearing that the treating surgeon told the woman that the surgery would improve both her appearance and her vision; it was further revealed that the surgeon regarded the risk of sympathetic opthalmia as being so remote that he did not disclose it to her. The Court, however, took a different view and affirmed that health professionals (and the surgeon in this case) have a stringent duty to disclose information that an individual patient may require — including being warned about the material risks of given treatments — ‘even when the patient does not seek information through specific questions’ (Kerridge et al 2005: 218; see also Forrester & Griffiths 2005: 96). In North America a similar stance has been assumed with legal scholars arguing that, in addition to being given information about material risks, patients should also be given information on how to ask any additional questions that may occur to them during the ongoing process of their care (Dickens & Cook 2004: 313).

All models depend on the further consideration of a patient’s rational or legal competence — a matter that, rightly or wrongly, only the courts can decide (the question of patient competency will be considered later in this discussion).

Whatever the legal considerations and arguments for or against these models, from a moral point of view (and, indeed, a pragmatic point of view) neither is free of difficulties. For example, the reasonable doctor standard can be unreliable on account of doctors often being reluctant to testify against their colleagues. Commenting on Australia’s medical defence unions, Stephen Rice writes (1988: 124):

… the medical defence unions operating in Australia claim they do not object to their members testifying against colleagues. But they stress to members in newsletters: — ‘Avoid unnecessary criticism of the work or conduct of other practitioners.’

The reasonable patient and ‘subjective person’ standards, however, can also be unreliable. For example, who is to say what is to count as a ‘reasonable’ patient, hypothetical or otherwise? Is it realistic to believe and accept that an abstract ‘hypothetical reasonable and competent adult’ — divorced from any cultural, social, historical and spiritual context of living — is able to represent reliably and truthfully what an actual person whose ‘reasonableness’ is at issue would ultimately desire? What one patient or ‘subjective person’ might consider reasonable, another might equally reject; and vice versa. The case of Jehovah’s Witnesses and their well- recognised refusal to accept life-saving blood transfusions is a point in question. It is not difficult to imagine a ‘reasonable patient’ of the Jehovah’s Witness faith refusing a blood transfusion against an overwhelming body of public opinion that such a refusal was ‘unreasonable’ and even ‘mad’ or ‘idiotic’.

The case of children (mature minors) reasonably refusing burdensome medical treatment against adult opinion is another example. A particular example of this can be found in the controversial English case involving a 15-year-old girl who underwent a heart transplant by order of a British High Court. The girl did not want the transplant explaining ‘I would feel different with someone else’s heart — that is a good enough reason not to have a heart transplant, even if it saved my life’ (Boseley & Dyer 1999: 19). Treating doctors and the Court disagreed, however, and the girl’s wishes were overridden on the ‘reasonable’ grounds that the heart transplant would save her life.

In dealing with these and other difficulties, as well as with other more general objections which may be raised against the doctrine of informed consent, it is important not to lose sight of the various theoretical perspectives underpinning and justifying the right of people to make informed choices about their care and treatment. For instance, key to both the legal doctrine and moral right of informed consent is (1) the liberal democratic notion of the sovereignty of the individual, and (2) ethical principlism, considered under separate subheadings below.

Informed consent and the sovereignty of the individual

Informed consent rests heavily on the view that the individual is sovereign alias the sovereignty of the individual. This highly individualistic notion characterises the person (patient) as a solitary competent individual who possesses ‘a sphere of protected activity or privacy free from unwanted interference’; by this view, although ‘influence is acceptable’, coercion in any form is not (Kuczewski 1996: 30). Kuczewski explains that (p 30):

Within this zone of privacy, one is able to exercise his or her liberty and discretion. Within this protected sphere take place disclosure, comprehension, and choice, which express the patient’s right of self-determination … The person is opaque to others and therefore the best judge and guardian of his or her own interests. Although the physician may be the expert on the medical ‘facts’, the patient is the only individual with genuine insight into his [sic] private sphere of ‘values’. Because treatment plans should reflect personal values as well as medical realities, the patient must be the ultimate decision-maker.

One serious and significant implication of this view is that the patient’s family, friends and/or chosen carers (acknowledging here that not all patients have families or, if they do, desire the involvement of their families) are conceived ‘as comprising competing interests’; they are also seen as having no entitlements whatsoever in regard to any consent to medical treatment processes that the ‘sovereign individual’ might otherwise engage in (Kuczewski 1996). This may help to explain some of the tensions examined previously in Chapter 4 (pages 78, 80, 91) in regard to family members of traditional cultural backgrounds seeking active participation in consent to medical treatment processes and the reluctance by some doctors and nurses to involve these family members in such processes.

Bioethicists and clinicians (particularly palliative care physicians) are, however, rethinking their traditional opposition to the involvement of family or chosen carers in consent to treatment practices (Chaboyer 2000). There is increasing recognition that illness can seriously undermine the patient’s capacity to make prudent self-determined choices (autonomy) and to be an effective judge and guardian of his or her own self-interests. This has been matched by an increasing questioning of the traditional legalistic approach to informed consent that, among other things, presupposes that the values of the ‘sovereign individual’ are well developed, fixed and adequate to the task of choosing between difficult treatment options, and that all the chooser needs in order to make an informed choice is ‘information’ (Gert 2002; Kuczewski 1996).

Increasingly, as previously discussed in Chapter 4 of this book, family members and chosen carers are recognised as having a vital role to play in consent processes and care of loved ones. By being intimately acquainted with (‘knowing well’) the patient, family members or chosen carers are able to provide appropriate and meaningful feedback to their loved ones, and to generally assist in ‘reality checking’ their loved one’s choices and the values, beliefs (new and old), and deliberations influencing these choices. In sum, the involvement of family members and/or chosen carers in consent to treatment processes can play a vital role in restoring the otherwise diminished autonomy of their sick loved ones (Kuczewski 1996). Furthermore, by fulfilling this role, they are also able to strengthen the bonds of their relationship with the patient and with each other — in short, to express their care of and for each other.

Informed consent and ethical principlism

Informed consent also rests heavily on ethical principlism (discussed in Chapter 3 of this book), both for its content and justification as an action guide. The principles of particular importance here include those of:

▪ autonomy — which demands respect for patients as self-determining choosers, and justifies allowing them the option of accepting risks

▪ non-maleficence — which demands the protection of patients from battery, assault, trespass, exploitation and other harms that may result from inadequate or inappropriate consent processes (including the inadequate or inappropriate disclosure of information)

▪ beneficence — which demands the maximisation of patient wellbeing via consent processes

▪ justice — which demands fairness and that patients not be unduly or intolerably burdened by consent processes.

It should be noted that while autonomy is a value underlying the doctrine of informed consent it is not the value, nor an absolute value. As Faden and Beauchamp (1986: 18) point out, at best autonomy is only a prima-facie value, and to regard it as having overriding value would be both historically and culturally ‘odd’. This is not to say that autonomy does not have a significant place in a moral approach to informed consent. It merely means that it does not have a sole place, and can be justly restricted by other competing moral principles, such as those already mentioned.

Having now reviewed the function and theoretical underpinnings of informed consent, let us proceed critically to examine the constituents and nature of informed consent.

The elements of an informed and valid consent

It is generally recognised within bioethics that disclosure, comprehension, voluntariness, competence and consent itself form the analytical components of the concept of informed consent (Faden & Beauchamp 1986: 274).

Morally speaking, for a consent to be regarded as informed, it must satisfy a number of criteria, including those relating to the informational aspect of the consent and those relating to the giving of consent itself. Beauchamp and Childress (2001: 77–98) argue that for consent to be informed: there must be a disclosure of all the relevant information (including both benefits and risks); the patient must fully understand (comprehend) both the information which has been given and the implications of giving consent; the consent must be voluntarily given (i.e. the patient must be free of coercion or manipulation); and, lastly, the patient must be competent to consent (i.e. be both ‘rational’ and prudent). Faden and Beauchamp (1986: 54) argue along similar lines, and recommend what they believe are less ‘over demanding’ and plausible criteria, notably:

(1) a patient or subject must agree to an intervention based on an understanding of (usually disclosed) relevant information, (2) consent must not be controlled by influences that would engineer the outcome, and (3) the consent must involve the intentional giving of permission for an intervention.

It needs to be noted that patients frequently do not realise that in giving consent they are not merely acknowledging the receipt of information concerning a recommended medical treatment or procedure, but are also actually giving permission to an attending health professional to go ahead and perform the treatment or procedure in question.

Faden and Beauchamp’s (1986) foundational work and theory of informed consent is probably one of the most comprehensive to date, and one which, although written from the cultural perspective of the US, deserves to be given serious attention by those furthering the informed consent debate in Australia, New Zealand and other common law countries. As well as advancing their ethical theory, these authors also make a number of useful practical suggestions on how informed consent practices could be made more ‘workable’.

It should be noted that the doctrine of informed consent has been the subject of much controversy, most notably among health professionals. Common objections include:

▪ obtaining an informed consent is unacceptably time-consuming

▪ when patients are told the information they need to know, they forget it

▪ most patients do not want to know all the details of the risks and benefits associated with a recommended medical treatment or procedure, and forcing information on them would be just as paternalistic as withholding it

▪ most patients would not understand the information required to make an informed choice

▪ giving information to patients can be harmful (e.g. they might refuse a life-saving procedure or drug because of a negligible risk)

▪ informed consent is impractical and thus unworkable.

These and similar objections are, however, difficult to sustain in the face of research findings, anecdotes and professional experience. For example, it is well recognised that people in stressful and unfamiliar situations are vulnerable both to information overload and short-term memory loss. The stress of being admitted to hospital; of coping with feelings of pain, fear and anxiety; of being separated from the familiarity of one’s home, family and friends; the general disruption of one’s life, not to mention the effort required to adapt to a new (hospital) environment characterised by strange smells, sights, noises, tastes, routines, faces, procedures and sensations — may all contribute to lessening an individual’s capacity to pay attention to and to recall information that has been disclosed. It is thus understandable that patients might sometimes forget or have their capacity to understand the information that has been given to them compromised by these factors.

To complicate matters, health professionals seeking consent or giving information do not always manage their encounters with patients very well. Some use a hurried, uninterested and sometimes intimidating approach when seeking a patient’s consent. When seeking consent from a patient, health professionals may fail to give due attention to such things as: controlling their tone of voice, choosing a suitable time and place to approach the patient, ensuring privacy, using the appropriate body language and facial expressions, choosing the right words, avoiding complicated jargon, sitting at the patient’s level, being generally respectful, and so on.

When dealing with non-English-speaking patients, these problems are considerably worse. For example, health professionals may shout unnecessarily (a problem which also sometimes occurs when they are dealing with blind or physically handicapped people who nevertheless have perfect hearing), or they may use inappropriate body language and facial expressions, use the wrong intonations in speech, or use terms which cannot be readily interpreted into the patient’s spoken language.

As far as patients who do not want to know the details of an impending medical procedure are concerned, there are few who seem to fit into this category. In some instances patients have declined information (on the basis of personal and cultural health beliefs and practices), but even then only certain select pieces of information have been declined; in these instances, patients have not voiced a blanket and unconditional rejection of all relevant information. In many instances, what has superficially appeared to be a ‘refusal’ was in fact more a demand that the information be given in a culturally appropriate manner (see discussion in Chapter 4 of this book). If, however, patients do make an informed and authentic choice not to receive certain relevant pieces of information, and on reflection are not open to changing their minds about receiving the information in question, then to give this information to the patients would certainly count as a paternalistic act (the subject of ‘paternalism’ will be considered shortly below).

The objection that patients would not be able to understand the necessary information in order to make an intelligent and informed choice is also difficult to sustain. It is sometimes difficult to avoid the impression that the claim that a patient cannot understand is more an assumption than a matter of sound deliberation and determination. Buchanan (1978: 386), for example, argues that to assume a patient would not understand given information is to make a ‘dubious and extremely broad psychological generalisation’, which, of course, ordinary doctors and nurses are not particularly qualified to make. Faden and Beauchamp (1986) also argue that most patients are able to understand the information given to them, and, what is more, that a patient’s level of understanding can be ascertained and measured.

Even if patients do not fully understand the information given, this does not always imply that it is the fault of the patient. A patient’s inability to understand may be directly related to a doctor’s or a nurse’s inappropriate behaviour and communication (Roth et al 1983: 176). The onus then is on those seeking to obtain consent to improve their approach to patients, and to presume a patient’s ability to understand information rather than an inability to understand. On this point Muyskens (1982a: 119) argues:

as in a court of law in which one’s innocence is presumed until proven otherwise, the client’s ability to comprehend and understand what is going on and to be able to make judgments based on the data must be presumed until firm evidence establishes the contrary.

Just as there is no compelling evidence to suggest that patients would not understand information disclosed to them about a proposed medical or nursing procedure, there is no compelling evidence to suggest that patients would be unduly injured or harmed by disclosures. Bok (1980) has long contended that very few patients withdraw their consent when informed of material risks or other so-called ‘harmful’ pieces of information concerning a proposed medical procedure. She further contends that in fact ‘it is what patients do not know but vaguely suspect that causes them corrosive worry’ (Bok 1980: 234).

Buchanan (1978) is even more critical of the view that the disclosure of information material to a treatment decision may cause harm to patients, arguing that such a view reeks of nothing more than wide and unfounded ‘psychiatric generalisations’, which ordinary doctors and nurses are not qualified to make. He argues further that even qualified psychiatric specialists would probably find it very difficult to judge correctly whether a patient would be significantly harmed by disclosure.

The ‘information causing harm’ objection, of course, also ignores the point that, even if a patient refused to undergo a recommended medical procedure on the basis of information received about certain material risks, this is, after all, something which any competent patient is morally entitled to do — whatever the risks involved and regardless of what others might think of their refusal (see also Tweeddale 2002; Forrester & Griffiths 2005; Kerridge et al 2005). At best, all attending health professionals can morally do is to persuade patients non-coercively about the known benefits of undergoing a given medical procedure; but they are not entitled to interfere with the patient’s choice if such persuasion fails (Faden & Beauchamp 1986).

Even if critics concede that these objections cannot be sustained, the objection still remains that informed consent procedures are impractical because they are unrealistically and unacceptably time-consuming. It is likely that obtaining a voluntary consent (i.e. one free of coercive or manipulative influences) and informed consent from a patient will take more time than obtaining an involuntary and uninformed consent. Nonetheless, health professionals have a responsibility to take the time required to interact and communicate with their patients in a way that facilitates making informed choices and realising morally just outcomes. Moreover, there can be no excuse (except possibly in an emergency life-threatening situation) for denying patients the time needed to deal with an anxiety, to answer a worrisome question, or to be reassured. Patients must have sufficient time to make an adequate decision and must have sufficient time to contemplate viable and real alternatives; anything less may result in information overload and may undermine their ability to make voluntary and informed choices (Faden & Beauchamp 1986: 326).

In a culture so heavily dominated and constrained by considerations of ‘time’, it may be tempting to accept ‘time constraint’ as a valid reason for abrogating one’s moral responsibilities. This, however, is not acceptable morally. Moreover there are many ways in which the difficulties posed by time constraints can be overcome. One possible solution is to involve others (including lawful proxies, family and/or chosen carers) in the processes of transferring and sharing information with patients. While it is obviously and properly the responsibility of treating doctors to obtain informed consents to medical treatment from the patients they are treating, there is nevertheless considerable room to suggest that a collaborative approach to meeting patients’ information needs would contribute substantially to maximising the patients’ moral interests.

Rightly or wrongly, nurses already play a major, although unacknowledged, role in meeting patients’ information needs. This situation has arisen for many reasons, including the problem that treating doctors sometimes fail, for various reasons, to meet the information needs of their patients. In situations like this, an attending nurse is often the only immediately available person patients (and their families) have to turn to in order to obtain the information they want. Indeed, nurses are very often the ones whom patients ask directly about what to expect of a given or pending medical procedure or treatment. In such instances, nurses can find themselves in a very difficult situation — particularly if an attending doctor will not respond appropriately to a patient’s request for information. The nurses’ dilemma is compounded by the fact that they know they can contribute a great deal to allaying patient anxiety related to knowledge deficits concerning proposed and rendered medical care and treatment options, but do not have the legitimated authority to undertake this role. Thus, if and when they are giving information to patients about medical treatments, nurses know they are ‘taking a risk’, since this could be construed as ‘interfering with the physician–patient relationship’ — as, indeed, has happened in a number of high-profile legal cases (see Johnstone 1994).

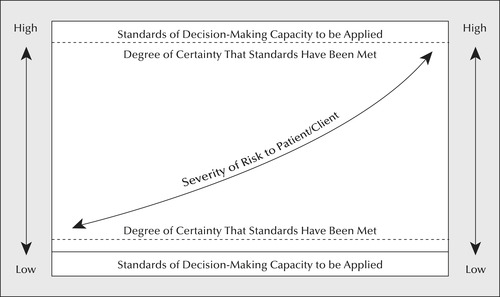

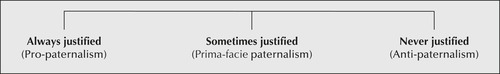

Studies have long shown that nurses can greatly assist patients in coming to understand their illness experience and physician directives given during medical consultations (Uyer 1986). One study also shows that the task of giving information to patients and satisfying patients’ information needs is ‘ impossible without systematic collaboration between medical and nursing staff’ (Engstrom 1986, emphasis added). It is clear that this is a matter which requires much greater attention than it has been given up until now with a view towards legitimating the role of nurses in meeting patients’ information needs.