CHAPTER 58 Organ Transplantation

OVERVIEW OF TRANSPLANTATION

Societal mores also impose limitations. The scarcity of cadaveric organs creates a mismatch between the number of patients who need transplantation and the number who can undergo transplantation. Currently, there are over 93,000 persons on the waiting list for a solid organ transplantation, but only 17,000 transplants were done between January and July of 2006.1 Some European countries follow the doctrine of “presumed consent” for postmortem donation, but the United States does not. In recent years, transplant centers have attempted to expand the donor pool by harvesting organs from persons who have been declared dead secondary to cardiac arrest (i.e., non–heart-beating donors) in addition to harvesting organs from persons who have been declared dead by neurological criteria (i.e., brain death). In response to this problem, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) created a committee to study ways in which the supply of transplantable organs can be increased. The committee’s report, released in May 2006, recommended the following: vigorous public education about organ donation; provision of more opportunities for registration as an organ donor; easier access to state donor registries; and renewed attention to improvement of organ procurement systems.2

Organ donation by living donors is an increasingly important potential source of transplantable kidneys, livers, and lungs. This is especially true in Japan where there are no defined criteria for determination of brain death and therefore few cadaveric organs are available for harvest.3 In the United States, living donors may be related to the recipient; unrelated but emotionally connected; or anonymous, altruistic strangers. In 2006, 4,252 transplanted kidneys came from deceased donors and 3,751 kidney transplants came from live donors. Parent-to-child liver transplantation (of the left lateral lobe) is an option, as is adult-to-adult transplantation of the right hepatic lobe. Living-lung donation is also an option for carefully selected candidates, but it requires a lower lobe from two different donors for each single potential recipient. The source of the donated organ, that is, from a deceased donor or living donor, does not affect recipient outcome.

Living organ donation raises several ethical questions: for example, “What is true informed consent regarding both short- and long-term risks for the donor?” and “Is the donor’s offer (be it from an emotionally connected or unrelated person) truly voluntary?” It is difficult to determine what level of risk is acceptable for a healthy, altruistic donor.4

Several retrospective studies of the long-term medical and psychological sequelae in living organ donors have been conducted. Short-term risks for live kidney donors include the morbidity secondary to surgery and anesthesia (e.g., bleeding and infection) and salary loss during the weeks of recovery. For kidney donors, long-term health risks include the development of microalbuminuria and the potential for renal failure in the remaining kidney. Approximately 0.1% of live kidney donors in the United States have been placed on the waiting list for a kidney transplant.5 To date, no deaths have resulted from living lobar lung donation, but donors do lose 15% to 20% of their total lung volume and often experience a decrease in exercise capacity.6 Adult-to-adult liver donation carries a significant degree of morbidity, and mortality rate estimates approach 1%. As of March 2003, there have been seven deaths among live partial-liver donors. In addition, two adult donors have required liver transplantation. This procedure is currently under investigation by the National Institute of Health (NIH) and the American College of Transplant Surgeons. Recent literature suggests that right lobectomy in a donor is less risky if the remnant liver volume is greater than 35% of the total liver volume.7 The long-term effects of giving up over half of one’s total liver volume are still unknown.

In the United States, the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), a nonprofit organization, endowed by Congress but reporting to the Department of Health and Human Services, regulates the allocation and distribution of donor organs. UNOS has two branches: the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (OPTN) and the Scientific Registry. The OPTN divides the country into 11 distinct geographical regions, and each region has its own waiting list. The length of time spent on the waiting list can differ among regions. Determination of priority is organ specific. For kidneys, the length of time on the waiting list is the primary determining factor, although full human leukocyte antigen (HLA) compatibility confers priority. Pediatric recipients (those patients age 12 and under) for kidneys and livers take priority over adults. The Lung Allocation Score (LAS) is a calculated score for patients over 12 years of age that represents severity of illness and the likelihood of a successful transplant outcome. That score, in addition to blood type and distance from the hospital where the donor organs are located, determines waiting-list placement for potential lung transplantation recipients. The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) is also a calculated score that predicts how urgently a patient over 12 years of age will need a transplant within the next 3 months. The only exception to the MELD system is a special category known as “Status 1.” Status 1 patients have suffered acute hepatic failure and might die within hours or days without a transplant. Tables 58-1 and 58-2 list the LAS and MELD criteria.

Table 58-1 Criteria for Lung Allocation Score (LAS)* (Age 12 and Older)

| Diagnosis Age Body mass index (BMI) Presence of diabetes New York Heart Classification of functional status Distance walked in 6 minutes Forced vital capacity (FVC) Pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) Creatinine Continuous oxygen requirement Requirement for ventilatory support |

* Adapted from United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS): www.unos.org.

Table 58-2 Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD)* (Age 12 and Older)

| Bilirubin (BR) Prothrombin time (international normalized ratio [INR]) Creatinine |

| Score ranges from 6-40 Represents urgency for need of transplant within 3 months of calculation |

* Adapted from United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS): www.unos.org.

PSYCHIATRIC EVALUATION OF THE TRANSPLANT PATIENT

Pretransplant Psychiatric Evaluation

There are no universally accepted guidelines for the psychiatric evaluation of potential candidates for organ transplanta tion and little reliable or predictive data regarding “suitability for transplantation.” Some centers routinely offer a face-to-face clinical interview with a mental health provider, whereas other centers administer formal psychological testing or offer a structured or semistructured interview. Transplant centers differ in their determination of who is an “acceptable” candidate and what degree of risk they are willing to assume. Common psychosocial and behavioral exclusion criteria include active substance abuse, active psychotic symptoms, suicidal ideation (with intent or plan), dementia, or a felony conviction. Relative contraindications include poor social supports with inability to arrange for pretransplant or posttransplant care, personality disorders that interfere with a working relationship with a transplant team, nonadherence to a medication regimen, and neurocognitive limitations8 (Table 58-3).

Table 58-3 Psychosocial Exclusion Criteria for Lung Transplantation

| Absolute Active substance abuse Active psychotic symptoms that interfere with function Suicidal ideation with intent or plan Dementia |

| Relative Poor social supports Personality disorders that cause interpersonal difficulties with members of the transplant team Nonadherence to medication regimen or to recommendations for procedures |

The issue of substance abuse in the pretransplant population is particularly important. Most transplant programs require 6 months to 1 year of sustained sobriety before initiation of the transplant evaluation, but selection criteria differ widely. In general, adult liver transplantation programs deem ongoing alcohol or drug use an absolute contraindication to transplantation.9 Some programs require patients to participate in a substance abuse counseling program in addition to Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) or Narcotics Anonymous (NA) as a prerequisite for listing if they appear to be at high risk for relapse. Cigarette smoking or any form of tobacco use is an absolute contraindication to lung transplantation. Patients must demonstrate 6 months to 1 year of abstinence from cigarettes and undergo random measurements of urinary cotinine and/or serum carboxyhemoglobin as part of the evaluation process. Liver transplantation programs have less stringent rules about tobacco use in potential recipients.10 In the end, individual transplant centers must determine what degree of risk they are willing to tolerate.

Pretransplant Psychiatric Disorders

Usually, there is a significant wait between the time of listing for transplant and the actual transplant itself. Many patients with heart failure must wait in a hospital’s intensive care unit (ICU) attached to a cardiac monitor or an intraaortic balloon pump (IABP). Years can go by while the patient with lung disease waits at home, sometimes far from a transplant center, becoming gradually sicker and more sedentary. The wait is stressful. A call from a member of the transplant team saying that an organ is available can come at any time or not at all. Sometimes a patient arrives at the hospital only to learn that the quality of the harvested organs is not good enough—the so-called “false start.” Loss of physical strength and productivity (with accompanying role change within the family or community) can lead to adjustment disorders and to depression.

The prevalence of major depression in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is unknown, but estimates range from 5% to 22%.11 Dialysis, disorders in endocrine function (such as hyperparathyroidism), and chronic anemia can also contribute to depression. The dialysis-disequilibrium syndrome with resultant cerebral edema, as well as uremia itself, can precipitate a change in mental status or even a frank encephalopathy. Patients with renal failure are prone to delirium from the accumulation of toxins (e.g., aluminum) or prescribed medications that are normally cleared through the kidney.

Patients with cardiac failure are also at risk for depression and delirium. These patients can spend long periods in the ICU awaiting transplantation with little contact with the world outside. Delirium can be caused by decreased cerebral blood flow, by multiple small ischemic events, or by IABP treatment.12 The development of the left ventricular assist device (LVAD) as a bridge to heart transplantation offers a chance for improved quality of life and functional status in this population.

TREATMENT OF THE PRETRANSPLANT PATIENT

The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are usually the first-line treatment of depressive disorders, given their benign side-effect profile and anxiolytic effects. For patients who also struggle to refrain from cigarette smoking, bupropion may be a good choice. Antidepressants are metabolized in the liver, and it is wise to use lower doses for patients with hepatic disease. In addition, there is some evidence to suggest that SSRIs can put patients at increased risk for upper gastrointestinal bleeding and therefore should be used with caution in patients with portal vein hypertension and with cirrhosis.13 SSRIs must also be used with caution in patients with resistant bacterial infections who require the antibiotic linezolid (a weak monoamine oxidase inhibitor [MAOI]) because of the risk of serotonin syndrome.14 With the exception of paroxetine, the SSRIs are well tolerated in patients with ESRD. Likewise, clearance of venlafaxine is reduced in renal failure and the metabolites of bupropion hydrochloride (which are excreted by the kidney) may accumulate and cause seizures in these vulnerable patients.11

Psychotherapy can also be an extremely important therapeutic intervention for patients approaching transplant. Even the relatively brief psychiatric pretransplant evaluation can serve as a good opportunity for patients to share their hopes and dreams for the future, as well as their fears of ongoing illness and of death either before or after transplant. Some psychiatrists will refer pretransplant patients to other mental health providers for therapy because they feel that they cannot maintain the patients’ confidentiality and continue to report to other members of the transplant team (personal communication, TransplantPsychiatry@googlegroups.com, 2006). Common issues raised in psychotherapy include grief over loss of productivity, guilt over dependent status, adaptation to changing role within the family and community, sexual dysfunction, cognitive slowing secondary to medication, and conflict between the reluctance to wish anyone ill and the desire for a deceased donor’s organ.

CARE OF THE POSTTRANSPLANT PATIENT

Short-term Care

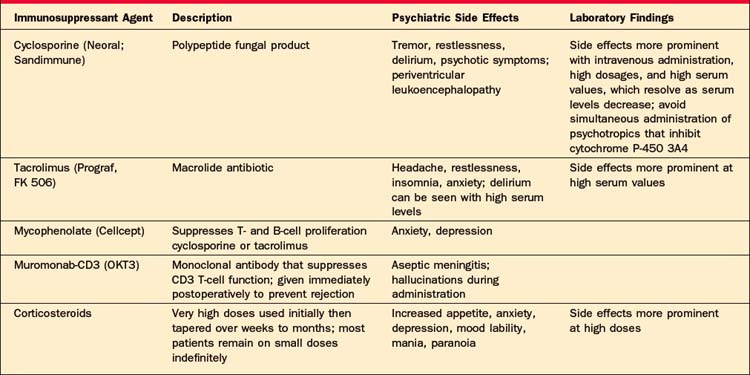

The hallmark of the early postoperative period for almost all transplant patients is delirium. The etiology can be multifactorial but usually represents a combination of medication effects or withdrawal states, metabolic changes, or infectious processes. Heart transplantation patients are at risk for intraoperative cerebral ischemia that may predispose them to delirium in the very early postoperative period. Lung transplantation patients may become hypoxic. All of the immunosuppressive medications can cause psychotic symptoms (such as paranoid delusions and auditory and visual hallucinations [with or without accompanying delirium]). Cyclosporine and tacrolimus can also cause a periventricular leukoencephalopathy that can manifest as an acute mental status change. High-dose steroids can also precipitate psychotic symptoms (Table 58-4).

Early symptoms of depression (e.g., mood changes, sleep disturbance, irritability, and poor concentration) may be secondary to medications (such as beta-blockers or steroids) or may represent a recurrence of a premorbid mood disorder. Sometimes, new symptoms of depression herald the development of infectious processes (such as cytomegalovirus [CMV] or Mycobacterium avium complex [MAC]). Treatment with the SSRIs can be helpful both for their antidepressant and anxiolytic effects.

PEDIATRIC TRANSPLANTATION

In 2006, pediatric patients accounted for approximately 7% (1,387) of all organ transplants done in the United States (19,719).1 Fifty percent of those transplants were for children between ages 11 and 17 years.

Pretransplant Evaluation

As with adults, there are no standardized tools to guide the psychiatric evaluation of children who face organ transplantation. Unlike with adults, however, the order and style of the interview depend on the child’s age and developmental stage. With a prepubertal child, it is appropriate to meet first with the parents or guardians to obtain a coherent, chronological history and to assess the parents’ understanding of the risks and benefits, as well as their history of compliance in obtaining care for their child. With an adolescent, it is helpful to interview the child alone, before speaking with the parents, in order to support his or her independence and wish for autonomy. Again, the psychiatric evaluation should address the following issues: presence of significant Axis I disorders (such as mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and learning disabilities) in the patient or in a caregiver; history of past or current substance abuse; relationship with caregivers; patient’s and family’s motivation for transplant; ability of the caregivers to comply with treatment recommendations (medication regimen and appointments); adequacy of social supports; and assessment of stressors within the family, such as marital discord or financial problems.

Posttransplant Care

Evidence suggests that the extent to which pediatric patients with life-threatening illnesses feel traumatized both by the procedure and by its sequelae correlates with the parents’ sense of stress.15 Parents’ perception of and reaction to the life-threatening nature of the illness, the surgical procedure, and the risks following the transplant can also affect the child’s risk for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Pediatric organ transplant recipients experience symptoms of PTSD at rates comparable to those of children with other life-threatening conditions. Interestingly, the likelihood of experiencing such symptoms (e.g., reexperiencing, having flashbacks, or manifesting avoidance) does not seem to be related to the type of organ transplant and is more common in those adolescents with relatively mild complications. This reinforces the “subjective” nature of both the parents’ and patients’ response to the traumatic event.16

In general, however, pediatric transplant patients do well. They feel better, return to school, and resume many of their activities. They do not demonstrate significant new psychopathology, although premorbid psychiatric illness may recur. Pediatric liver transplantation patients demonstrate significant neuropsychological deficits and developmental delays in intellectual and academic functioning, both before and after transplantation, thought to be related to the effect of chronic liver disease on the developing brain.17 Standard doses of immunosuppressive medication may also interfere with academic performance in vulnerable children (personal communication, September 2006), but this has not been systematically studied.

1 United Network for Organ Sharing Available at www.unos.org. (accessed October 28, 2006).

2 Childress JF. How can we ethically increase the supply of transplantable organs? Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(3):224-225.

3 Nudeshima J. Obstacles to brain death and organ transplantation in Japan. Lancet. 1991;338:1063-1066.

4 Surman OS. The ethics of partial-liver donation. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1038.

5 Ingelfinger JR. Risks and benefits to the living donor. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:447-449.

6 Prager LM, Wain JC, Roberts DH, Ginns LC. Medical and psychological outcome of living lobar lung transplant donors. ISHLT. 2006;25(10):1206-1212.

7 Kim SJ, Kim DG, Chung ES, et al. Adult living donor liver transplantation using the right lobe. Transplant Proc. 2006;38(7):2117-2120.

8 Dobbels F, Verleden G, Dupont L, et al. To transplant or not? The importance of psychosocial and behavioral factors before lung transplantation. Chronic Respiratory Disease. 2006;3:39-47.

9 Levenson JL, Olbrisch ME. Psychosocial screening and selection of candidates for organ transplantation. In: Trzepacz PT, DiMartini AF, editors. The transplant patient. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

10 Krahn LE, DeMartini AF. Psychiatric and psychosocial aspects of liver transplantation. Liver Transplantation. 2005;11(10):1157-1168.

11 Cohen LM, Tessier EG, Germaine MJ, Levy NB. Update on psychotropic medication use in renal disease. Psychosomatics. 2004;45:34-48.

12 Sanders KM, Stern TA, O’Gara PT, et al. Delirium during IABP therapy: incidence and management. Psychosomatics. 1992;33:35-44.

13 Weinrieb R, Auriacombe M, Lynch KG, et al. A critical review of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor–associated bleeding: balancing the risk of treating hepatitis C–infected patients. J Clin Psych. 2003;64:1502-1510.

14 Taylor JJ, Wilson JW, Estes LL. Linezolid and serotonergic drug interactions: a retrospective survey. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(2):180-187.

15 Stuber ML, Kazak AE, Meeske K, et al. Predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms in childhood cancer survivors. Pediatrics. 1997;100:958-964.

16 Mintzer LL, Stuber ML, Seacord D, et al. Traumatic stress symptoms in adolescent organ transplant recipients. Pediatrics. 2003;115:1640-1644.

17 Stewart SM, Hiltebeitel C, Nici J, et al. Neuropsychological outcome of pediatric liver transplantation. Pediatrics. 1991;87(3):367-376.