CHAPTER 55 Catatonia, Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome, and Serotonin Syndrome

CATATONIA

Definition

The catatonic syndrome comprises a constellation of motor and behavioral signs and symptoms that often occurs in relation to neuromedical insults. Structural brain disease, intrinsic brain disorders (e.g., epilepsy, toxic-metabolic derangements, infectious diseases), a variety of systemic disorders that affect the brain, and idiopathic psychiatric disorders (such as affective and schizophrenic psychoses) have each been associated with catatonia. Catatonia was first named and defined in 1847 by Karl Kahlbaum, who published a monograph that described 21 patients with a severe psychiatric disorder.1 This was among the first studies in the area of mental illness to use the symptom-based approach of Sydenham to diagnose disorders without a known etiopathogenesis.

Kahlbaum believed that patients with catatonia passed through several phases of illness: a short stage of immobility (with waxy flexibility and posturing), a second stage of stupor or melancholy, a third stage of mania (with pressured speech, hyperactivity, and hyperthymic behavior), and finally, after repeated cycles of stupor and excitement, a stage of dementia.1

Kraepelin,2 who was influenced by Kahlbaum, included catatonia in the group of deteriorating psychotic disorders named “dementia praecox.” Bleuler3 adopted Kraepelin’s view that catatonia was subsumed under severe idiopathic deteriorating psychoses, which he renamed “the schizophrenias.”

Nevertheless, catatonia was strongly linked with schizophrenia until the 1990s, and until fairly recently catatonia could only be diagnosed as a schizophrenia in an obvious nosological error. Thanks in large part to the work of Fink and Taylor,4 the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), now includes new criteria for mood disorders with catatonic features and for catatonic disorder secondary to a general medical condition, as well as for the catatonic type of schizophrenia.5 Catatonia, whether a consequence of medical illness, major depression, mania, a mixed affective disorder, or schizophrenia, is diagnosed when the clinical picture includes at least two of the following five features: motoric immobility (as evidenced by catalepsy [including waxy flexibility] or stupor); excessive motor activity (that is apparently purposeless and not influenced by external stimuli); extreme mutism or negativism (that is characterized by an apparently motiveless resistance to all instructions or by the maintenance of a rigid posture against attempts to be moved); peculiarities of voluntary movement (such as the voluntary assumption of an inappropriate or bizarre posture, stereotyped movement, prominent mannerism, or grimace); or echolalia (or echopraxia).

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

The rate of catatonia in the general psychiatric population varies according to study design and diagnostic criteria. Nevertheless, prospective studies on patients hospitalized with acute psychotic episodes place the incidence of catatonia in the 7% to 17% range.6 In patients who suffer from mood disorders, rates have ranged from 13% to 31% over the last century. Catatonia appears commonly in those with bipolar disorder.7 Others at particular risk include patients with mixed manic episodes and those with severe mood disorders.6 Some have contended that the incidence of catatonia has diminished in schizophrenia, but here too diagnostic and study design variations make this interpretation problematic.

Catatonia is a nonspecific syndrome associated with a variety of etiologies.6 Neuromedical “organic” etiologies account for 4% to 46% of cases in various series. This underscores the need for a thorough neuromedical workup when catatonic signs are present. Personality disorders or conversion disorder is cited as etiologic in from 4% to 11% of catatonia cases. Catatonia is idiopathic in 4% to 46% of cases in various case series.

Subtypes

Several subtypes of catatonia have been described. Catatonic withdrawal is characterized by psychomotor hypoactivity, whereas catatonic excitement is characterized by psychomotor hyperactivity. These presentations may alternate during the course of a catatonic episode. Kraepelin identified a “periodic” catatonia (with an onset in adolescence) characterized by intermittent excited states, followed by catatonic stupor and a remitting and relapsing course.8 In the 1930s this disorder was further described as lethal catatonia, distinguished by the rapid onset of a manic delirium, high temperatures, catatonic stupor, and a mortality rate in excess of 50%.

A dominant gene effect in families with periodic catatonia has been noted, with more parents than siblings afflicted.9 The disease locus maps onto chromosome 15q15 in families with periodic catatonia.9 However, in one family the locus was on chromosome 22q13, with WKL1 as the associated gene.10 This gene codes for a cation channel protein found in limbic and dorsal striatal tissue, suggesting that mesolim-bic and nigrostriatal changes may be involved in periodic catatonia.

Mann and co-workers11 reviewed the literature on lethal catatonia and found that cases from the preneuroleptic era classically began with 8 days of intense, uninterrupted motor excitement; it was fatal in more than three out of four cases. Afflicted patients were often bizarre and violent, refused to eat, and manifested intermittent mutism, posturing, catalepsy, and rigidity that alternated with excitement. Thought was disorganized, speech was incoherent, and delusions and hallucinations were present. When hyperactive they were febrile, diaphoretic, and tachycardic. This stage would be followed by exhaustion, characterized by stupor and by high temperatures.

For Kraepelin, lethal catatonia was a syndrome with various neuromedical and psychiatric etiologies; Mann and co-workers’11 review of 292 cases since 1960 supports this concept. Sixty percent of patients who received neuroleptics died. The “classic” hyperactive form of catatonia was found in two-thirds of the cases. High fever, altered consciousness, autonomic instability, anorexia, electrolyte imbalance, cyanosis, and associated catatonic signs (e.g., posturing, stereotypies, and mutism) were present from the early stages; stupor typically followed, but it was the initial manifestation in nearly one-third of patients. Once stupor and rigidity emerged, patients were clinically indistinguishable from those with NMS.12

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Signs and symptoms of the catatonic syndrome are outlined in Table 55-1 (the Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale). Catatonia may be caused by a host of syndromes (Table 55-2).13 Efforts should of course be made to identify the etiology of catatonia and to treat it if possible.

| Catatonia can be diagnosed by the presence of 2 or more of the first 14 signs listed below. | |

The full 23-item Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS) measures the severity of 23 signs on a 0-3 continuum for each sign. The first 14 signs combine to form the Bush-Francis Catatonia Screening Instrument (BFCSI). The BFCSI measures only the presence or absence of the first 14 signs, and it is used for case detection. Item definitions on the two scales are the same.

From Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, et al: Catatonia I. Rating scale and standardized examination, Acta Psychiatr Scand 93:129-136, 1996.

Table 55-2 Potential Etiologies of the Catatonic Syndrome

| Primary Psychiatric |

| Acute psychoses Conversion disorder Dissociative disorders Mood disorders Obsessive-compulsive disorder Personality disorders Schizophrenia |

| Secondary Neuromedical |

| Cerebrovascular |

| Other Central Nervous System Causes |

| Akinetic mutism Alcoholic degeneration and Wernicke’s encephalopathy Cerebellar degeneration Cerebral anoxia Cerebromacular degeneration Closed head trauma Frontal lobe atrophy Hydrocephalus Lesions of thalamus and globus pallidus Narcolepsy Parkinsonism Postencephalitic states Seizure disorders Surgical interventions Tuberous sclerosis |

| Neoplasm |

| Angioma Frontal lobe tumors Gliomas Langerhans’ carcinoma Paraneoplastic encephalopathy Periventricular diffuse pinealoma |

| Poisoning |

| Coal gas Organic fluorides Tetraethyl lead poisoning |

| Infections |

| Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome Bacterial meningoencephalitis Bacterial sepsis General paresis Malaria Mononucleosis Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis Tertiary syphilis Tuberculosis Typhoid fever Viral encephalitides (especially herpes) Viral hepatitis |

| Metabolic and Other Medical Causes |

| Acute intermittent porphyria Addison’s disease Cushing’s disease Diabetic ketoacidosis Glomerulonephritis Hepatic dysfunction Hereditary coproporphyria Homocystinuria Hyperparathyroidism Idiopathic hyperadrenergic state Multiple sclerosis Pellagra |

| Idiopathic |

| Peripuerperal Systemic lupus erythematosus Thrombocytopenic purpura Uremia |

| Drug-Related |

| Neuroleptics (typical and atypical); clozapine and risperidone (all neuroleptics have been associated) |

| Nonneuroleptic |

| Alcohol Antidepressants (tricyclics, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and others) Anticonvulsants (e.g., carbamazepine, primidone) Aspirin Disulfiram Metoclopramide Dopamine depleters (e.g., tetrabenazine) Dopamine withdrawal (e.g., levodopa) Hallucinogens (e.g., mescaline, phencyclidine, and lysergic acid diethylamide) Lithium carbonate Morphine Sedative-hypnotic withdrawal Steroids |

| Stimulants |

| Amphetamines, methylphenidate, and possibly cocaine |

Most common medical conditions associated with catatonic disorder from literature review done by Carroll BT, Anfinson TJ, Kennedy JC, et al: Catatonic disorder due to general medical conditions, J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 6:122-133, 1994.

From Philbrick KL, Rummans TA: Malignant catatonia, J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 6:1-13, 1994.

Fortunately, while no one test can confirm the diagnosis of catatonia, some studies (e.g., the electroencephalogram [EEG], neuroimaging of the brain, optokinetic and caloric testing) may help identify the etiology. A personal and family history of psychiatric illness is important although not diagnostic. Research on regional cerebral blood flow has shown basal ganglia asymmetry (with left-sided hyperperfusion), hypoperfusion in the left medial temporal area, and decreased perfusion in the right parietal cortex. During working memory tasks and with emotional-motor activation, the orbitofrontal cortex appears to be altered in several cases studied with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).14

The specific number and nature of the signs and symptoms required to make a diagnosis of catatonia remains controversial. Lohr and Wisniewski15 proposed that one or more cardinal features (including catalepsy, positivism [such as seen in automatic obedience], and negativism), and two of the other features should be present to diagnose catatonia. Rosebush and colleagues16 suggested that catatonia was present when three cardinal features (e.g., immobility, mutism, and withdrawal [with refusal to eat or drink]) or when two cardinal features and two secondary characteristics were present.

Taylor17 contended that even one cardinal characteristic conveys as much clinical confidence (in the diagnosis and treatment) as the presence of seven or eight characteristics. The evidence does not support a relationship among the number of catatonic features, the diagnosis, and response to treatment. Fink and Taylor4 later considered that a minimum of two classic symptoms was sufficient to diagnose the syndrome, and more recently, Bush and colleagues18 developed a rating scale and guidelines for the diagnosis of catatonia. They found that two or more signs identified all of their patients with catatonia. Their standardized examination method is consistent with the DSM-IV criteria for catatonia (Table 55-3).

Table 55-3 Standardized Examination for Catatonia

|

The method described here is used to complete the 23-item Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS) and the 14-item Bush-Francis Catatonia Screening Instrument (BFCSI). Item definitions on the two scales are the same. The BFCSI measures only the presence or absence of the first 14 signs.

|

|

| Procedure

3. The arm should be examined for cogwheeling. Attempt to reposture and instruct the patient to “keep your arm loose.” Move the arm with alternating lighter and heavier force.

4. Ask the patient to extend his or her arm. Place one finger beneath his or her hand and try to raise it slowly after stating, “Do not let me raise your arm.”

|

|

| Activity level | Waxy flexibility |

| Abnormal movements | Gegenhalten |

| Abnormal speech | Mitgehen |

| Echopraxia | Ambitendency |

| Rigidity | Automatic obedience |

| Negativism | Grasp reflex |

From Fricchione G, Bush G, Fozdar M, et al: Recognition and treatment of the catatonic syndrome, J Intensive Care Med 12:135-147, 1997.

Pathophysiology

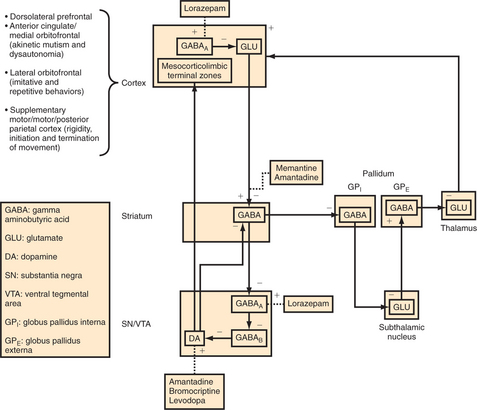

Catatonia is thought to reflect a disruption in basal ganglia thalamocortical tracts (including the motor circuit [rigidity], the anterior cingulate/medial orbitofrontal circuit [akinetic mutism and perhaps through lateral hypothalamic connections hyperthermia and dysautonomia], and the lateral orbitofrontal circuit [imitative and repetitive behaviors]) (Figure 55-1).19 Such disruption may lead to a relative state of hypodopaminergia in these circuits through reduced flow in the medial forebrain bundle, the nigrostriatal tract, and the tuberoinfundibular tract. DA activity in the dorsal striatum and in the ventral striatum and paralimbic cortex is thus reduced perhaps secondary to reduced GABAA inhibition of GABAB substantia nigra (SN) and ventral tegmentum (VTA) interneurons. This would lead to a dampening of DA outflow, whereas activation at GABAA through use of agonists, such as lorazepam, would indirectly disin-hibit DA cell activity.20,21 Another possible site of pathophysiology involves reduced GABAA inhibition of frontal corticostriatal tracts leading to NMDA changes in the dorsal striatum and indirectly in the SN and VTA.20 Multiple etiologies, if they affect the basal ganglia, thalamus, or paralimbic or frontal cortices, will have the potential to cause these neurotransmitter alterations that will disrupt basal ganglia thalamocortical circuits, leading to the phenomenology of catatonia.

Management and Treatment

Whatever its etiology, catatonia is accompanied by significant morbidity and mortality rates from systemic complications. In addition, many of the physical illnesses responsible for catatonia can be hazardous, causing many complications (Table 55-4). Thus, timely diagnosis and treatment are essential. If a neurological or medical condition is found, treatment for that specific illness is indicated. Occasionally psychiatric therapies will be used to treat catatonia as a secondary behavioral manifestation of a medical illness. For example, lorazepam has been found to be effective in certain cases of catatonia secondary to medical illness, and it has become the first-line treatment for catatonia regardless of etiology, as discussed later.16 Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been used to treat lupus patients with catatonia22 and other secondary catatonias and remains the most effective treatment for catatonia.23 Two or three ECT treatments are usually sufficient to lyse the catatonic state in routine cases, though a course of four to six treatments is usually given to prevent relapse, and ten to twenty treatments are sometimes needed in difficult cases. Fatality rates of 50% or more were the rule before the introduction of ECT.24

Table 55-4 Some Medical Complications Associated with Catatonia

| Simple Nonmalignant Catatonia |

| Aspiration Burns Cachexia Dehydration and its sequelae Pneumonia Pulmonary emboli Thrombophlebitis Urinary incontinence Urinary retention and its sequelae |

| Malignant Catatonia |

| Acute renal failure Adult respiratory distress syndrome Cardiac arrest Cheyne-Stokes respirations Death Dysphagia due to muscle spasm Disseminated intravascular coagulation Electrocardiographic abnormalities Gait abnormalities Gastrointestinal bleeding Hepatocellular damage Hypoglycemia (sudden and profound) Intestinal pseudo-obstruction Laryngospasm Myocardial infarction Myocardial stunning Necrotizing enterocolitis Respiratory arrest Rhabdomyolysis and sequelae Seizures Sepsis Unresponsiveness to pain |

Modified from Philbrick KL, Rummans TA: Malignant catatonia, J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 6:1-13, 1994.

Intravenous (IV) amobarbital also leads to rapid resolution in some patients with catatonic stupor.25 However, these effects tend to be short-lived.

Neuroleptics have been frequently used to treat catatonia. In addition to the variable response of catatonia to these drugs, neuroleptics may complicate matters; their use also has precipitated catatonic reactions and NMS.12 At times higher doses of antipsychotics are used to treat psychosis and agitation, but it may worsen catatonia. Moreover, among the 292 patients with malignant catatonia reviewed by Mann and colleagues,11 78% of those solely treated with a neuroleptic died, compared with an overall mortality rate of 60%.

In 1983, both Lew and Tollefson26 (reporting on the usefulness of IV diazepam) and Fricchione and colleagues27 (reporting on the benefit of IV lorazepam given to patients in neuroleptic-induced catatonic states [including NMS]) suggested the use of IV benzodiazepines in primary psychiatric catatonia.

Bush and colleagues28 studied the use of lorazepam and ECT in the treatment of catatonia. With a drug distribution that is less rapid and less extensive, a relatively high plasma level can be maintained, thus prolonging the clinical benefit of IV lorazepam.29 A switch to regular doses of lorazepam or diazepam maintains the therapeutic effect. Lorazepam given orally or via nasogastric tube in a daily dose of 6 to 20 mg has also been used effectively. Diazepam (10 to 50 mg/day) and clonazepam (1 to 5 mg/day) also have been used successfully, as has midazolam.29 If lorazepam is unsuccessful, ECT should be considered.29

In a study of lorazepam treatment for NMS, rigidity and fever abated in 24 to 48 hours, whereas secondary features of NMS dissipated within 64 hours (without adverse effects).30

Philbrick and Rummans13 reviewed 18 cases of malignant catatonia; 11 out of 13 patients treated with ECT survived, whereas only 1 out of 5 not treated with ECT survived. In terms of NMS, 39 cases of ECT treatment have been reported; 34 of them improved. The message is clear—when a patient has malignant catatonia of any type, ECT should be used expeditiously. Muscle relaxants, calcium channel-blockers, carbamazepine, anticholinergics, lithium, thyroid medication, stimulants, and corticosteroids have each been anecdotally associated with resolution of catatonia.13 Adrenocorticotropic hormone and corticosteroids also have been reported to work in cases of lethal catatonia.11 Dopaminergic agents, such as bromocriptine and amantadine, have been used successfully in NMS.31 In a retrospective review of 734 cases, Sakkas and colleagues32 concluded that these agents and the muscle relaxant dantrolene led to improvement; bromocriptine and dantrolene also were associated with a significant reduction in the mortality rate. However, in a prospective study of 20 patients, Rosebush and colleagues33 found that bromocriptine and dantrolene were not efficacious.

In 1985, when it was suggested that psychogenic catatonia and neuroleptic-induced catatonia (including NMS) shared a common pathophysiology, use of specific dopaminergic or GABA-ergic drugs in psychogenic catatonia untreated by neuroleptic medication also was suggested.21 Accordingly, it is of interest that oral bromocriptine was used successfully for catatonia that preceded neuroleptic exposure.34

Catatonia secondary to schizophrenia may be less responsive to lorazepam. In these patients, IV amantadine (available in Europe) and more recently memantine have shown some effectiveness in isolated cases, suggesting NMDA antagonist therapeutics in this condition.35,36

Even if lorazepam has been helpful in lysing the catatonic state, the patient will often still be left with psychotic symptoms and may eventually need antipsychotic medications. A reasonable approach is to try an atypical neuroleptic while maintaining the patient on lorazepam as a buffer against reemergence of catatonia. If the catatonia has been malignant as in NMS, a waiting period of approximately 2 weeks is justified, although there are no systematic studies confirming this. Indeed, rechallenging a patient who has had NMS with an antipsychotic is controversial. Most investigators suggest that antipsychotics should not be given until at least 2 weeks after an episode of NMS has resolved and that rechallenge should be with an atypical or with a typical neuroleptic of a lower potency. Table 55-5 reviews management principles of catatonia.

Table 55-5 Principles of Management of Catatonia

Modified from Philbrick KL, Rummans TA: Malignant catatonia, J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 6:1-13, 1994.

Prognosis and Complications

In patients with catatonia, the long-term prognosis is fairly good in almost half the cases.37 Those with an acute onset, depression, or a family history of depression have a better prognosis.38 Periodic catatonias have good short- and long- term prognoses. Neuromedically-induced catatonias vary in prognosis in relation to their particular etiologies. Treatment with ECT offers a good short-term prognosis for most catatonias, and maintenance ECT may often improve long-term prognosis.

See Table 55-4 for medical complications associated with simple and malignant catatonias.

NEUROLEPTIC MALIGNANT SYNDROME

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Estimates of the risk for NMS have varied widely (from 0.02% to more than 3%). Different diagnostic criteria, survey techniques, population susceptibilities, prescribing habits, and treatment settings all contribute to the variance. In one center with a large number of patients treated with antipsychotics, 1 out of every 500 to 1,000 patients was thought to develop NMS.39 Age and gender do not appear to be reliable risk factors, though young adult males may be more prone to extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). The fact that NMS occurs around the world suggests that environmental factors are not significant predictors. While NMS can occur in association with any disorder treated with a neuroleptic, certain conditions may elevate the risk of NMS. A history of catatonia is a major risk for progression to the malignant catatonia of NMS. Schizophrenia, mood disorders, neuromedical “organic” brain disorders, alcoholism, and substance abuse disorders have each been associated with NMS. The period of withdrawal from alcohol or sedative-hypnotics may increase the risk of NMS due to aberrant thermoregulation and autonomic dysfunction. Agitation, dehydration, and exhaustion may also increase the risk for NMS. Basal ganglia disorders (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, Wilson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and tardive dystonia) are thought to place patients at increased risk. Low serum iron appears to be a state-specific finding in NMS, and patients with low serum iron in the context of catatonia may be at greater risk for NMS if placed on neuroleptic medications. A history of NMS conveys the risk of recurrence, with up to one-third of patients having a subsequent episode when rechallenged. High-potency neuroleptics have been thought to produce an elevated risk and more intense cases of NMS. Clozapine, for example, may cause NMS with significantly less rigidity. Nevertheless, use of atypicals does cause NMS. It should be noted that withdrawal from antiparkinsonian agents or lorazepam has been reported to cause NMS-like states. Studies have not supported any particular genetic predisposition, although case reports have implicated an association with CYP2D6.39

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Philbrick and Rummans13 suggested using the term malignant catatonia rather than lethal catatonia (since not all cases are lethal) to describe critically ill cases marked by autonomic instability or hyperthermia (in contradistinction to cases of simple, nonmalignant catatonia). The causes of malignant catatonia are the same as those of simple catatonia. Pernicious catatonia has also been used to describe this catatonic variant.40

Neuroleptics have been viewed as potential causes because NMS is considered a severe form of neuroleptic-induced catatonia. NMS is a syndrome associated with the use of neuroleptics and characterized by autonomic dysfunction (with tachycardia and elevated blood pressure), rigidity, mutism, stupor, and hyperthermia (associated with diaphoresis), sometimes in excess of 42° C. Hyperthermia is reported in 98% of cases.39 The rigidity can become “lead-pipe” in nature. Parkinsonian features, including cogwheel rigidity, may be present. NMS (most often in the setting of atypical antipsychotic use) may occur without rigidity or other EPS or creatine phosphokinase (CPK) elevation. Mental status changes occur in 97% of cases.39 Most often the NMS patient will be in a catatonic state akin to akinetic mutism; such patients may be alert, delirious, stuporous, or comatose. Diagnostic criteria for NMS are found in Table 55-6,41 and their overlap with features of catatonia are displayed in Table 55-7.

Table 55-6 Diagnostic Criteria for Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

| Treatment with neuroleptics within 7 days of onset (2-4 weeks for depot neuroleptics) |

| Hyperthermia (≥ 38° C) |

| Muscle rigidity |

| Five of the following: |

Adapted from Caroff SN, Mann SC, Lazarus A, et al: Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: diagnostic issues, Psychiatr Ann 21:130-147, 1991.

Table 55-7 Catatonia and Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome: Associated Features

| NMS | Catatonia | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Signs | ||

| Hyperthermia | Yes | Often |

| Motor rigidity | Yes | Yes |

| Mutism | Yes | Yes |

| Negativism | Often | Yes |

| Altered consciousness | Yes | Yes |

BP, Blood pressure; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; NMS, neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

EEGs are abnormal in roughly half of cases, most often with generalized slowing that is consistent with encephalopathy.39 In contrast, computed tomography (CT) of the brain and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies are normal in 95% of NMS cases.39

In 1991 Rosebush and Mazurek22 found decreased levels of serum iron in NMS and suggested a role for lowered iron stores in the reduction of DA-receptor function.

Most commonly NMS develops over a few days, often beginning with rigidity and mental status changes followed by signs of hypermetabolism. The course is usually self-limited, lasting from 2 days to 1 month (once neuroleptics are stopped and supportive measures are begun).39 Persistent cases are usually secondary to use of depot neuroleptics and ECT is highly effective in these cases. Although the mortality rate has been reduced through better recognition and management, there is still an approximately 10% risk of death.39 Myoglobinuric renal failure may have long-term consequences.

SEROTONIN SYNDROME

Definition

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter involved in many psychiatric disorders. As serotonin levels increase, adverse central nervous system (CNS) effects and toxicity may arise. Heightened clinical awareness is necessary to prevent and to intervene when a toxic syndrome secondary to serotonin excess emerges. Serotonin syndrome (SS), as it is called, most commonly occurs as a result of an interaction between serotonergic agents and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). Signs of SS include mental status changes (e.g., confusion, anxiety, irritability, euphoria, and dysphoria), gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and incontinence), behavioral manifestations (e.g., restlessness and agitation), neurological findings (e.g., ataxia or incoordination, tremor, myoclonus, hyperreflexia, ankle clonus, and muscle rigidity), and autonomic nervous system abnormalities (e.g., hypertension, hypotension, tachycardia, diaphoresis, shivering, sialorrhea, mydriasis, tachypnea, and hyperthermia).42–44

Epidemiology

The incidence of SS is unknown. There are no data to suggest that gender differences confer any particular vulnerability to the syndrome. Given the overlap of symptoms with NMS, SS is often mistaken for it and thus may be underreported. The existence of the syndrome in varying degrees also may confound its recognition, as can unawareness on the part of the majority of physicians.44 SS most often occurs in individuals being treated with psychotropics for a psychiatric disorder. It occurs in about 14% to 16% of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) overdose patients.45

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Based on his review of 38 cases, Sternbach46 proposed the first operational definition of the syndrome in humans. According to this schema, diagnosis requires the following three criteria: an increase in, or addition of, a serotonergic agent to an established medication regimen (in addition to least three of the following features: mental status changes, agitation, myoclonus, hyperreflexia, diaphoresis, shivering, tremor, diarrhea, and incoordination); other etiologies need to be ruled out; and a neuroleptic must not have been started or increased in dosage before the onset of the signs and symptoms previously listed.

Based on a review of other diagnostic criteria, Keck and Arnold42 modified Sternbach’s criteria to include mental status changes, agitation, restlessness, myoclonus, hyperreflexia, diaphoresis, tremor, shivering, incoordination, autonomic nervous system dysfunction, hyperthermia, and muscle rigidity. Most recently the so-called Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria were proposed.47 If a patient has been exposed to a serotonergic drug within the past 5 weeks and spontane ous clonus emerges, the patient has SS. If there is inducible clonus or ocular clonus plus either agitation or diaphoresis, SS is present. If there are tremor and hyperreflexia, SS can be diagnosed. If there are hypertonicity and temperature greater than 38° C and either ocular or inducible clonus, SS is present. This approach to SS diagnosis is hoped to be more sensitive to serotonin toxicity and less prone to produce false-positive cases.

The most common drug interactions associated with SS include MAOI-SSRI, MAOI–tricyclic antidepressant, and MAOI-venlafaxine combinations. In general, when an SSRI is used in combination with an MAOI, an SS is more likely to occur. Drugs associated with SS are included in Table 55-8.

| Enhanced Serotonin Synthesis |

| l-Tryptophan |

| Increased Serotonin Release |

| Cocaine Amphetamines Fenfluramine Dextromethorphan Meperidine 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “ecstasy”) Sibutramine |

| Serotonin Agonists |

| Buspirone Dihydroergotamine (DHE) Lithium Meta-chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP) Sumatriptan Trazodone |

| Inhibited Serotonin Catabolism |

| Isocarboxazid Moclobemide Phenelzine Selegiline Tranylcypromine |

| Inhibited Serotonin Reuptake |

| Amitriptyline Bromocriptine Clomipramine Desipramine Dextromethorphan Fenfluramine Fluoxetine Fluvoxamine Imipramine Meperidine Mirtazapine Nefazodone Nortriptyline Paroxetine Pethidine Sertraline Tramadol Trazodone Venlafaxine |

Modified from Keck PE, Arnold LM: The serotonin syndrome, Psychiatr Ann 30:333-343, 2000, p 336.

Pathophysiology

From both animal and human studies, the role of 5-HT has been implicated in the pathogenesis of SS. Nucleus raphe serotonin nuclei (located in the midbrain and arrayed in the midline down to the medulla) are involved in mediating thermoregulation, appetite, nausea, vomiting, wakefulness, migraine, sexual activity, and affective behavior. Ascending serotonergic projections are likely to play a role in the presentation of SS, particularly in the development of hyperthermia, mental status, and autonomic changes. The 5-HT2A45 and 5-HT1A receptors appear to be overactive in this condition, which has led some to use 5-HT1A antagonists in the management of the SS. There also appears to be CNS norepinephrine overactivity. This is clinically significant since clinical outcomes may be associated with hypersympathetic tone.44 The roles of catecholamines and 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptor interactions are unclear, as are the contributions of glutamate, GABA, and DA.

Management and Treatment

Benzodiazepine management of agitation, even when mild, is essential in the SS. This is because benzodiazepines, such as diazepam and lorazepam, can reduce autonomic tone and temperature and thus may have positive effects on survival.44 Physical restraints should be avoided if at all possible because muscular stress can lead to lactic acidosis and to elevated temperature.

Specific 5-HT receptor antagonism has occasionally been advocated for the treatment or prevention of the symptoms associated with SS. Cyproheptadine, a 5-HT2A antagonist, has been recommended.44 Mirtazapine, a 5-HT3 and 5-HT2 antagonist, has also been used in a small number of cases. For hypertension, nitroprusside and nifedipine, and for tachycardia, esmolol, have been advocated.44 Since the rise in temperature is muscular in origin, antipyretics are of no use in SS, and paralytics are required when fever is high.

Prognosis and Complications

In SS, rhabdomyolysis is the most common and serious complication; it occurs in roughly one-fourth of cases.39 Generalized seizures occurred in approximately 10%, with 39% of these patients dying. Myoglobinuric renal failure accounted for roughly 5% of medical complications, as did diffuse intravascular coagulation (DIC). In those with DIC, nearly two-thirds died.

1 Kahlbaum K. Catatonia. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973. (translated by Y Levy and T Priden)

2 Kraepelin E: Dementia praecox and paraphrenia (facsimile edition), Huntington, NY, 1971, RE Krieger Publishing (translated by RM Barclay; edited by CM Robertson).

3 Bleuler E. Dementia praecox and the group of schizophrenia. New York: International University Press, 1950. (translated by J Zinkin)

4 Fink M, Taylor MA. Catatonia: a separate category in DSM IV? Integrative Psychiatry. 1991;7:2-5.

5 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, ed 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1994.

6 Caroff SN, Mann SC, Campbell EC, Sullivan KA. Epidemiology. In: Caroff SN, Mann SC, Francis A, Fricchione GL, editors. Catatonia: from psychopathology to neurobiology. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004.

7 Braunig P, Kruger S, Shugar G. Prevalence and clinical significance of catatonic symptoms in mania. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39:35-46.

8 Kraepelin E;ed 8 Psychiatrie;vol 3; 1913, Johann Ambrosius Barth Leipzig, Germany 806

9 Stober G, Saar K, Ruschendorf F, et al. Splitting schizophrenia: periodic catatonia-susceptibility locus on chromosome 15q15. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:1201-1207.

10 Meyer J, Huberth A, Ortega G, et al. A missense mutation in a novel gene encoding a putative cation channel is associated with catatonic schizophrenia in a large pedigree. Mol Psychiatry. 2001;6:302-306.

11 Mann SC, Caroff SN, Bleier HR, et al. Lethal catatonia. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:1374-1381.

12 Caroff S. The neuroleptic malignant syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 1980;41:79-83.

13 Philbrick KL, Rummans TA. Malignant catatonia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;6:1-13.

14 Northoff G. Neuroimaging and neurophysiology. In: Caroff SN, Mann SC, Francis A, Fricchione GL, editors. Catatonia: from psychopathology to neurobiology. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 2004.

15 Lohr JB, Wisniewski AA. Catatonia. In: Lohr JB, Wisniewski AA, editors. The neuropsychiatric basis of movement disorders. Baltimore: Guilford Press, 1987.

16 Rosebush PI, Hildebrand AM, Furlong BG, et al. Catatonic syndrome in a general psychiatric inpatient population: frequency, clinical presentation, and response to lorazepam. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51:357-362.

17 Taylor MA. Catatonia: a review of a behavioral neurologic syndrome. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1990;3:48-72.

18 Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, et al. Catatonia I. Rating scale and standardized examination. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93:129-136.

19 Mann SC, Caroff SN, Fricchione GL, Campbell EC, Greenstein RA. Malignant catatonia. In: Caroff SN, Mann SC, Francis A, Fricchione GL, editors. Catatonia: from psychopathology to neurobiology. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004.

20 Fricchione G, Bush G, Fozdar M, et al. Recognition and treatment of the catatonic syndrome. J Intensive Care Med. 1997;12:135-147.

21 Fricchione GL. Neuroleptic catatonia and its relationship to psychogenic catatonia. Biol Psychiatry. 1985;20:304-313.

22 Rosebush PI, Mazurek MF. Serum iron and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Lancet. 1991;338:149-151.

23 Clothier JL, Pazzaglia P, Freeman TW. Evaluation and treatment of catatonia (letter). Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:553-554.

24 Fink M. Catatonia. In: Trimble M, Cummings J, editors. Contemporary behavioral neurology. Oxford: Butterworth/Heinemann, 1997.

25 Dysken MW, Kooser JA, Haraszti JS, Davis JM. Clinical usefulness of sodium amobarbital interviewing. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36:789-794.

26 Lew TY, Tollefson G. Chlorpromazine-induced neuroleptic malignant syndrome and its response to diazepam. Biol Psychiatry. 1983;18:1441-1446.

27 Fricchione GL, Cassem NH, Hooberman D, Hobson D. Intravenous lorazepam in neuroleptic induced catatonia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1983;3:338-342.

28 Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, et al. Catatonia: II. Treatment with lorazepam and electroconvulsive therapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93:137-143.

29 Fink M, Bush G, Francis A. Catatonia: a treatable disorder, occasionally recognized. Direct Psychiatry. 1993;13:1-7.

30 Francis A, Chandragiri S, Rizvi S: Lorazepam therapy of the neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, May 30-June 4, 1998, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

31 Caroff SN, Mann SC. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Med Clin North Am. 1993;77:185-202.

32 Sakkas P, Davis JM, Hua J, et al. Pharmacotherapy of neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Psychiatr Ann. 1991;21:157-164.

33 Rosebush PI, Stewart T, Mazurek MF. The treatment of neuroleptic malignant syndrome: are dantrolene and bromocriptine useful adjuncts to supportive care? Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:709-712.

34 Mahmood T. Bromocriptine in catatonic stupor. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:437-438.

35 Northoff G, Lins H, Boker H, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist amantadine in febrile catatonia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19:484-486.

36 Thomas C, Carroll BT, Maley JT, et al. Memantine in catatonic schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:656.

37 Levenson JL, Pandurangi AK. Prognosis and complications. In: Caroff SN, Mann SC, Francis A, Fricchione GL, editors. Catatonia: from psychopathology to neurobiology. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004.

38 Morrison JR. Catatonia: prediction of outcome. Compr Psychiatry. 1974;15:317-324.

39 Mann SC, Caroff SN, Keck PE, Lazarus A. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and related conditions, ed 2. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2003.

40 Kalinowsky LB. Lethal catatonia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:1106-1107.

41 Caroff SN, Mann SC, Lazarus A, et al. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: diagnostic issues. Psychiatr Ann. 1991;21:130-147.

42 Keck PE, Arnold LM. The serotonin syndrome. Psychiatr Ann. 2000;30:333-343.

43 Reddick B, Stern TA. Catatonia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and serotonin syndrome. In Stern TA, Herman JB, editors: Psychiatry update and board preparation, ed 2, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

44 Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1112-1120.

45 Isbister GK, Bowe SJ, Dawson A, Whyte IM. Relative toxicity of selective serotonin uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in overdose. J Toxicol Clin Toxical. 2004;42:277-285.

46 Sternbach H. The serotonin syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:705-713.

47 Dunkley EJC, Isbister GK, Sibbritt D, et al. The Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria: simple and accurate diagnostic rules for serotonin toxicity. Q J Med. 2003;96:635-642.

Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1112-1120.

Caroff SN, Mann SC, Francis A, Fricchione GL, editors. Catatonia: from psychopathology to neurobiology. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004.

Fricchione G, Bush G, Fozdar M, et al. Recognition and treatment of the catatonic syndrome. J Intensive Care Med. 1997;12:135-147.

Gelenberg AJ. The catatonic syndrome. Lancet. 1976;1:1339-1341.

Mann SC, Caroff SN, Keck PE, Lazarus A. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and related conditions, ed 2. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2003.

Philbrick KL, Rummans TA. Malignant catatonia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;6:1-13.

Sternbach H. The serotonin syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:705-713.

Taylor MA. Catatonia: a review of a behavioral neurologic syndrome. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1990;3:48-72.