Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the cardiovascular system, principles of cardiac conduction, and basic dysrhythmia interpretation is needed.

• Knowledge of basic functioning of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) and patient response to ICD therapy is needed.

• Knowledge of principles of defibrillation threshold, antidysrhthmia medications, alteration in electrolytes, and effect on the defibrillation threshold is necessary.

• Advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) knowledge and skills are needed.

• Clinical and technical competence related to use of the external defibrillator is necessary.

• Indications for ICD implantation, based on the 2008 American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/ Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) guidelines6:

Survivors of cardiac arrest as a result of ventricular fibrillation (VF) or sustained unstable ventricular tachycardia (VT)

Survivors of cardiac arrest as a result of ventricular fibrillation (VF) or sustained unstable ventricular tachycardia (VT)

Patients with structural heart disease and sustained VT

Patients with structural heart disease and sustained VT

Patients with syncope of undetermined origin with hemodynamically significant VT or VF at electrophysiology study (EPS)

Patients with syncope of undetermined origin with hemodynamically significant VT or VF at electrophysiology study (EPS)

Patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) less than or equal to 35%, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II or III

Patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) less than or equal to 35%, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II or III

Patients with LVEF less than 35% as a result of prior myocardial infarction (MI; more than 40 days after MI), NYHA class II or III; or LVEF less than 30%, NYHA function class I

Patients with LVEF less than 35% as a result of prior myocardial infarction (MI; more than 40 days after MI), NYHA class II or III; or LVEF less than 30%, NYHA function class I

Patients with nonsustained VT as a result of prior MI, LVEF less than 40%, with inducible VF or sustained VT at EPS

Patients with nonsustained VT as a result of prior MI, LVEF less than 40%, with inducible VF or sustained VT at EPS

Patients with unexplained syncope, significant left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, nonischemic DCM

Patients with unexplained syncope, significant left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, nonischemic DCM

Patients with sustained VT with normal or near-normal ventricular function

Patients with sustained VT with normal or near-normal ventricular function

Patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) or arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD), with one or more major risk factors for sudden cardiac death (SCD)

Patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) or arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD), with one or more major risk factors for sudden cardiac death (SCD)

Patients with long QT syndrome who are having syncope or VT while receiving beta blockers

Patients with long QT syndrome who are having syncope or VT while receiving beta blockers

Patients who are not hospitalized and await transplantation

Patients who are not hospitalized and await transplantation

Patients with Brugada syndrome, with either syncope or with documented VT that has not resulted in cardiac arrest

Patients with Brugada syndrome, with either syncope or with documented VT that has not resulted in cardiac arrest

Patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic VT with syncope or documented sustained VT on beta blocker therapy

Patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic VT with syncope or documented sustained VT on beta blocker therapy

Patients with cardiac sarcoidosis, giant cell myocarditis, or Chagas’ disease

Patients with cardiac sarcoidosis, giant cell myocarditis, or Chagas’ disease

Class IIb: May be considered in:

Class IIb: May be considered in:

Patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy with LVEF less than or equal to 35%, NYHA functional class I

Patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy with LVEF less than or equal to 35%, NYHA functional class I

Patients with long QT syndrome and risk factors for SCD

Patients with long QT syndrome and risk factors for SCD

Patients with syncope and advanced structural heart disease in whom thorough invasive and noninvasive investigations have failed to define a cause

Patients with syncope and advanced structural heart disease in whom thorough invasive and noninvasive investigations have failed to define a cause

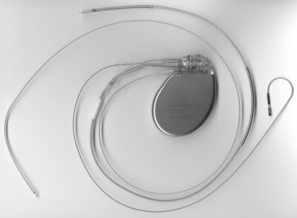

• The ICD system is composed of a pulse generator and a lead system. The pulse generator is titanium and contains the capacitors, circuitry, and a lithium battery (Fig. 50-1).

• Battery longevity may be greater than 6 years, depending on the number of times therapies are delivered and the frequency of pacing.5 The pulse generator is typically located in a pectoral subcutaneous pocket.

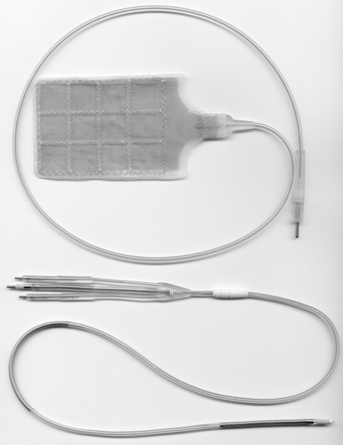

• The leads are insulated wires that sense the patient’s intrinsic rhythm and can pace or deliver therapies (Fig. 50-2). Leads are classified as atrial or ventricular, endocardial (transvenous) or epicardial (myocardial), unipolar or bipolar, and active or passive fixation.8 The lead systems may be single, double, or multiple.

• Leads may be attached to the heart via active or passive fixation. Active fixation leads use a screw, barb, or hook at the tip that is embedded into the myocardium to ensure stability of the lead. Passive fixation leads use tines or fins at the tip that allow the lead to attach to trabeculae of the myocardium.

• Most leads are endocardial (transvenous) leads and are inserted transvenously through the subclavian, cephalic, or axillary veins.

• Epicardial leads are less common but are used in special circumstances. Epicardial pacing leads may be placed on the outside of the left ventricular to provide biventricular pacing when coronary sinus placement of the LV lead has been unsuccessful. Epicardial patches may be placed on the outside of the heart, both anteriorly and posterior. Epicardial patches provide a greater surface area for defibrillation (See Fig. 50-2).

• All leads have a cathode (negative pole) and an anode (positive pole). A unipolar lead uses one conductor wire, with a distal electrode as cathode and the metal can as the anode. This configuration produces a large electrical circuit and a large pacing artifact on electrocardiography (ECG). Because of the large area covered, this configuration is susceptible to stimulation of chest muscles and also to electromagnetic interference. A bipolar lead uses two electrodes on the distal end of the lead to form the circuit. The cathode is located at the distal tip, and the anode several millimeters proximal to the tip. Because of the closer circuitry, a smaller pacing artifact is seen on ECG.

• All ICDs function as pacemakers. Some ICDs are also biventricular pacemakers. Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) paces the right and left ventricles together to establish synchrony in an effort to improve LV function. CRT is considered for patients with symptomatic heart failure, optimized medical therapy, LVEF less than 35%, and prolonged QRS duration of greater than 120 milliseconds.1 Biventricular pacing must be as close to 100% as possible for the greatest benefit. Biventricular pacing leads are placed in the right atrium, the right ventricle, and an epicardial vein on the surface of the left ventricle accessed through the coronary sinus.

• The ICD detects tachydysrhythmias, delivers antitachycardia pacing (ATP) or electrical therapy (shock), and provides bradycardia pacing. ATP attempts to convert monomorphic VT by pacing at a rate faster than the VT rate, thereby terminating the dysrhythmia. ATP is a painless way of treating VT, sometimes avoiding shock therapy altogether. The PainFree II trial demonstrated that compared with shocks, empirical ATP for fast VT was highly effective, equally safe, and, improved quality of life.17 Cardioversion is generally referred to as synchronized electrical therapy. Defibrillation is not synchronized and is generally used to convert ventricular dysrhythmias.

• The ICD therapies may be programmed from one to three zones. Typically, the zones are labeled as 1, VT, usually at slower VT rates of 140 to180 beats per minute (varies according to physician preference and patient situation); 2, fast VT, usually at rates in the range of 180 to 220 beats per minute or higher; and 3, VF for rates usually greater than 220 beats per minute. VT zones may be programmed for sequential therapies of ATP followed by electrical defibrillation if ATP is unsuccessful.

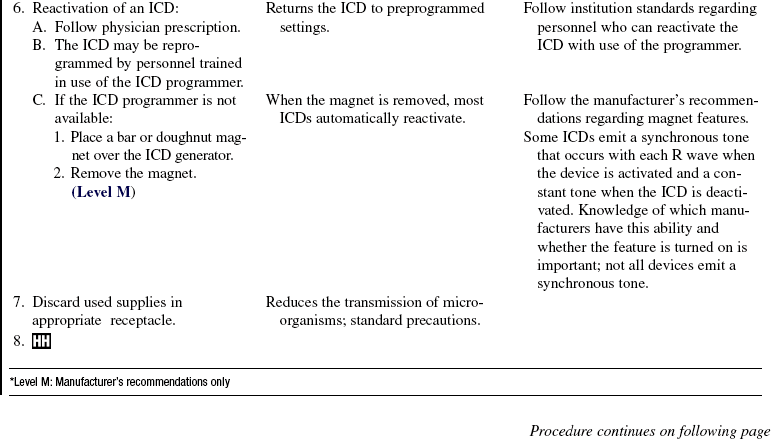

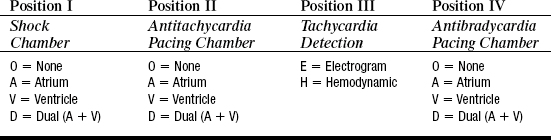

• A defibrillator code was developed in 1993 by the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology and the British Pacing and Electrophysiology Group to describe the capabilities and operation of ICDs. The defibrillator code is patterned after the pacemaker code; however, it has some important differences (Table 50-1).2 The defibrillator code offers less information about the ICD’s antibradycardia pacing function but more specific information about the shock functions.

Table 50-1

From Bernstein AD, et al., 1993. The NASPE/BPEG defibrillator code (NBD code). Pacing Clin Electrophysiol, 16, 1776, 1993.

• A magnet applied over an ICD disables the device therapies of ATP and electrical cardioversion/defibrillation but does not affect pacemaker function. The magnet is used during procedures that may cause electromagnetic interference (EMI). EMI from cautery devices, for example, may be improperly sensed as a tachydysrhythmia, causing inappropriate device shock. In most models, removal of the magnet restores normal ICD function. Some models, however, do not resume previous settings once the magnet is removed.9 Checking with the manufacturer before magnet use is best to determine the specific recommendations for each ICD. If a device programmer and trained personnel are available, device tachydysrhythmia detection and therapies can be disabled through the programmer for the duration of the procedure.

• Emotional adjustments vary with each patient and family. Patients may experience depression, anxiety, fear, and anger. Some patients view the device as an activity restriction, and others see it as a life-saving device that allows normal life to resume. Preimplantation psychologic variables, such as degree of optimism or pessimism, and an anxious personality style may place patients at a higher level of risk for difficulty adjusting to the ICD.13 Support groups may serve a vital role for ICD recipients who are anxious and for patients who may need additional support.10 Interventions to reduce psychologic distress and improve quality of life may reduce morbidity and mortality in these patients.3,11,12,15

• The option of ICD deactivation should be discussed before the device is implanted.18 Early discussions of device deactivation facilitate later discussions and are an important part of the informed consent process.

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Assess learning needs, readiness to learn, and factors that influence learning.  Rationale: This assessment allows the nurse to individualize teaching in a meaningful manner.

Rationale: This assessment allows the nurse to individualize teaching in a meaningful manner.

• Assess patient and family understanding of ICD therapy and the reason for its use.  Rationale: This assessment provides information regarding knowledge level and necessity of additional teaching.

Rationale: This assessment provides information regarding knowledge level and necessity of additional teaching.

• Provide information about the normal conduction system, such as structure of the conduction system, source of the heartbeat, normal and abnormal heart rhythms, symptoms of abnormal heart rhythms, and the potentially life-threatening nature of VT and VF.  Rationale: Understanding of the conduction system and dangerous dysrhythmias assists the patient and family in recognizing the seriousness of the patient’s condition and the need for ICD therapy.

Rationale: Understanding of the conduction system and dangerous dysrhythmias assists the patient and family in recognizing the seriousness of the patient’s condition and the need for ICD therapy.

• Provide information about ICD therapy, including the reason for the ICD, device operation, location of the device, types of therapy given by the device, risks and benefits of the device, and follow-up.  Rationale: Understanding of ICD functioning assists the patient and family in developing realistic perceptions of ICD therapy.

Rationale: Understanding of ICD functioning assists the patient and family in developing realistic perceptions of ICD therapy.

• Discuss postimplant incision care, including inspection of the incision and pocket. The incision is kept dry for several days after the procedure.  Rationale: The nurse or physician needs to know whether any of the following signs or symptoms of infection appear: redness, edema, warmth, drainage, and/or fever.

Rationale: The nurse or physician needs to know whether any of the following signs or symptoms of infection appear: redness, edema, warmth, drainage, and/or fever.

• Discuss postoperative activity. For the first 4 to 6 weeks after implant: 1, no lifting of the arm on the side of the ICD above the shoulder or extending the arm to back (including activities such as swimming, golfing, and bowling); 2, no lifting of items heavier than 10 lb; and 3, no excessive pushing, pulling, or twisting.  Rationale: The activity restrictions help to prevent new leads from dislodgment.

Rationale: The activity restrictions help to prevent new leads from dislodgment.

• Provide patients with an identification card (temporary cards are usually given to patients at the time of implant, and permanent cards are sent to patients by the manufacturer several weeks later). Encourage the patient to wear Medic Alert identification and to carry the identification card at all times.  Rationale: This identification ensures that appropriate information is available to anyone caring for the patient.

Rationale: This identification ensures that appropriate information is available to anyone caring for the patient.

• If patients are prescribed antidysrhythmic medication, stress the importance of continuing the medication.  Rationale: Antidysrhythmic medications suppress dysrhythmias and may limit potential ICD shocks.

Rationale: Antidysrhythmic medications suppress dysrhythmias and may limit potential ICD shocks.

• Discuss the need for patients to keep a current list of medications in their wallets.  Rationale: The patient or other family members should be prepared to provide necessary information to healthcare providers in an emergency situation.

Rationale: The patient or other family members should be prepared to provide necessary information to healthcare providers in an emergency situation.

• In select circumstances, the healthcare team may recommend that family members learn CPR.  Rationale: Family members may be more prepared for an emergency situation (e.g., if the ICD does not convert a life-threatening rhythm or the ICD malfunctions).

Rationale: Family members may be more prepared for an emergency situation (e.g., if the ICD does not convert a life-threatening rhythm or the ICD malfunctions).

• Educate patients and families about what to do for a device shock. The shock varies in intensity from mild to severe pain. If patients have received an isolated shock and are asymptomatic afterward, they should call their healthcare provider to determine further action (usually an appointment for device interrogation). If patients have received multiple shocks in a short period of time (within minutes to hours), or if they have had one shock and do not feel well, they should activate the emergency medical services (EMS) system by calling 911 to seek emergency evaluation at an emergency room.14  Rationale: Repeated shocks may indicate conditions that necessitate prompt treatment, such as electrolyte imbalance or ischemia. They may also indicate malfunction of the device sensing, which may occur with lead fracture.

Rationale: Repeated shocks may indicate conditions that necessitate prompt treatment, such as electrolyte imbalance or ischemia. They may also indicate malfunction of the device sensing, which may occur with lead fracture.

• Inform patients to call their healthcare provider if they hear an audible tone emitted from the device. An audible tone may indicate battery depletion or signal device parameter alerts (such as lead impedance out of normal range). Some devices use vibratory alerts in place of audible tones to signal an alert condition.  Rationale: The ICD should be interrogated to determine the reason for the tone and to ensure safe device function.

Rationale: The ICD should be interrogated to determine the reason for the tone and to ensure safe device function.

• Inform patients and families that family members are not harmed if they touch the patient when a shock is delivered.  Rationale: This information prepares the patient and family and may decrease anxiety.

Rationale: This information prepares the patient and family and may decrease anxiety.

• Driving restrictions vary from state to state and among physicians. Each patient should discuss plans for long trips and driving restrictions with the physician. Current guidelines prohibit anyone with an ICD from obtaining a commercial driver’s license.7  Rationale: These restrictions are intended to prevent motor vehicle accidents from sudden loss of consciousness while driving.

Rationale: These restrictions are intended to prevent motor vehicle accidents from sudden loss of consciousness while driving.

• Educate patients and families that the terms “elective replacement indicated” (ERI) and “end of life” (EOL) are used to describe the status of the battery. At ERI, the battery is able to function for approximately another 2 to 3 months. A generator change is done as soon as possible during that time period. At EOL, the generator must be changed promptly.  Rationale: This teaching prepares patients and families for generator changes, alleviates misunderstanding, and may decrease anxiety.

Rationale: This teaching prepares patients and families for generator changes, alleviates misunderstanding, and may decrease anxiety.

• Inform patients and family members about follow-up device checks or “interrogations.” Stress the importance of keeping these appointments. Devices are checked every 3 to 6 months (but may be more frequent if any issues arise that necessitate monitoring). Many follow-up checks are now done remotely, through internet-based systems. A transmitter device is mailed to the patient from the device manufacturer.  Rationale: Routine interrogation maintains optimal functioning of the ICD and alerts providers of dysrhythmias.

Rationale: Routine interrogation maintains optimal functioning of the ICD and alerts providers of dysrhythmias.

• Inform the patient and family of potential sources of EMI to the ICD. In the hospital, EMI include magnetic resonance imaging, diathermy, computed tomography, lithotripsy, electrocautery, radiation therapy, and nerve stimulators. Outside the hospital, these include handheld wands used by airport security, arc welders, large transformers or motors, antitheft devices at stores or libraries, cellular phones less than 6 inches away from the pulse generator, the antenna of an operating citizens’ band or ham radio, improperly grounded electrical equipment, and handheld tools less than 12 inches away from the pulse generator. Cellular phones should be positioned on the opposite side of device.16  Rationale: EMI can deactivate ICD therapies.

Rationale: EMI can deactivate ICD therapies.

• Explore the patient’s feelings about having an ICD. Approximately 30% to 50% of patients experience a degree of psychologic stress after implant.13 ICD support groups have been helpful to many.  Rationale: Acknowledging these stressors may alleviate the most common psychologic disturbances after ICD implantation, which include stress, anxiety, depression, and fear.

Rationale: Acknowledging these stressors may alleviate the most common psychologic disturbances after ICD implantation, which include stress, anxiety, depression, and fear.

• Inform patients to notify their physicians if the device begins to wear through the skin or the device site becomes reddened, warm, painful, or has discharge.  Rationale: These signs and symptoms identify problems (e.g., infection) that need additional medical care.

Rationale: These signs and symptoms identify problems (e.g., infection) that need additional medical care.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Assess the patient’s cardiac rate and rhythm.  Rationale: This assessment establishes baseline data.

Rationale: This assessment establishes baseline data.

• Presurgical instructions usually include withholding anticoagulation therapy as prescribed for several days before the procedure, maintaining nothing by mouth (NPO) for at least 8 hours before the procedure, and obtaining complete blood cell count (CBC), chemistries, prothrombin time (PT), and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) for baseline data.  Rationale: All these actions ensure patient safety to prevent complications such as excessive bleeding and aspiration.

Rationale: All these actions ensure patient safety to prevent complications such as excessive bleeding and aspiration.

• Assess the patency of the patient’s intravenous access.  Rationale: Intravenous access should be ensured for administration of prescribed medications.

Rationale: Intravenous access should be ensured for administration of prescribed medications.

• Administer antibiotics as prescribed.  Rationale: Antibiotics are administered to reduce infection from skin microorganisms such as Staphylococcus aureus (cause of early infection) and Staphylococcus epidermidis (cause of later infection).9

Rationale: Antibiotics are administered to reduce infection from skin microorganisms such as Staphylococcus aureus (cause of early infection) and Staphylococcus epidermidis (cause of later infection).9

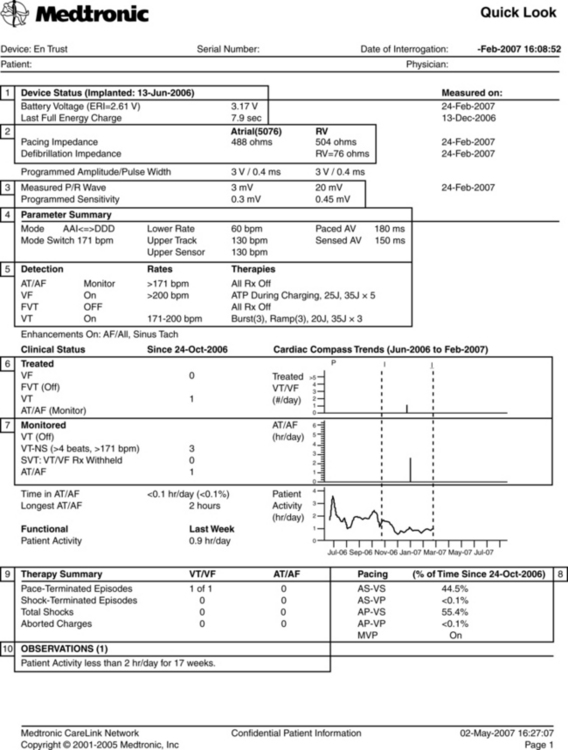

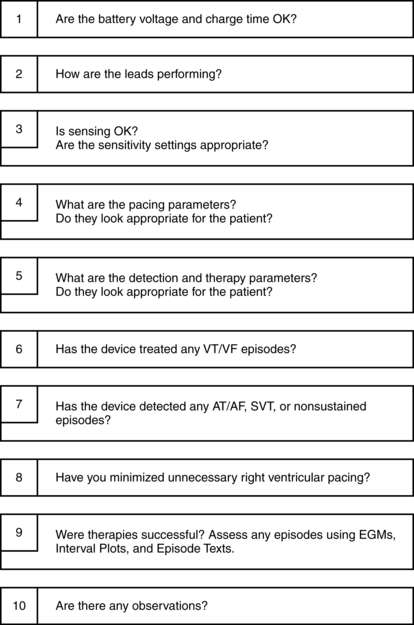

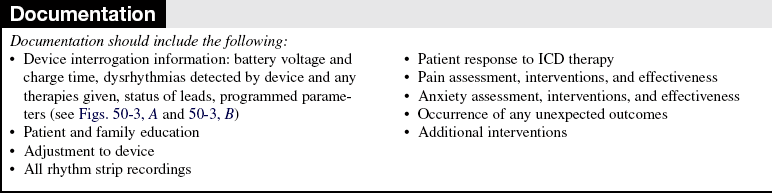

• Identify the manufacturer of the ICD and how it is programmed.  Rationale: Interrogation of the device provides important information: battery voltage and impedance, charge time, dysrhythmias detected by device (logbook) and any therapies given (ATP or shock), pacing and sensing thresholds, and impedances for all leads, percent of pacing and sensing in each chamber, and review of programmed parameters.19 Interrogation usually also reveals device and lead information (models and serial numbers), implant date, and implanting physician information. See Figure 50-3 for an example of an ICD interrogation report.

Rationale: Interrogation of the device provides important information: battery voltage and impedance, charge time, dysrhythmias detected by device (logbook) and any therapies given (ATP or shock), pacing and sensing thresholds, and impedances for all leads, percent of pacing and sensing in each chamber, and review of programmed parameters.19 Interrogation usually also reveals device and lead information (models and serial numbers), implant date, and implanting physician information. See Figure 50-3 for an example of an ICD interrogation report.

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that the patient and family understand pre-procedural teaching. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Ensure that informed consent has been obtained (before ICD insertion).  Rationale: Informed consent protects the rights of the patient and makes a competent decision possible for the patient.

Rationale: Informed consent protects the rights of the patient and makes a competent decision possible for the patient.

• Perform a pre-procedure verification and time out (before ICD insertion).  Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

• Provide analgesia or sedatives as prescribed and needed.  Rationale: Analgesia and sedatives promote comfort and may decrease anxiety.

Rationale: Analgesia and sedatives promote comfort and may decrease anxiety.

References

1. Abraham, WT, Yancy, CW, Cardiac resynchronization therapy. a practical guide for device optimization, part I. CHF 2006; 12:169–173.

![]() 2. Bernstein, AD, et al. The NASPE/BPEG defibrillator code (NBD code). Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1993; 16:1776.

2. Bernstein, AD, et al. The NASPE/BPEG defibrillator code (NBD code). Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1993; 16:1776.

3. Bostwick, JM, Sola, CL. An updated review of implantable cardioverter/defibrillators, induced anxiety, and quality of life. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007; 30(4):677–688.

![]() 4. Bubien, RS, et al. Defibrillation and resynchronization, AACN Clin Issues. 2004; 15(3):340–361.

4. Bubien, RS, et al. Defibrillation and resynchronization, AACN Clin Issues. 2004; 15(3):340–361.

5. Ellenbogen, KA, Wood, MA. Cardiac pacing & ICDs, ed 5. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2008.

6. Epstein, AE, et al, ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities. a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 Guideline Update for Implantation of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antitachydysrhythmia Devices) developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008; 51(21):e1–e61.

7. Esptein, AE, et al. Circulation. 2007; 115:1170–1176.

8. Hayes, DL, Asirvatham, SJ. Dictionary of cardiac pacing, defibrillation, resynchronization, and arrythmias, ed 2. Minneapolis, MN: Cardiotext Publishing, 2007.

9. McMullan, J, et al. Care of the pacemaker/implantable cardioverter-defibrillator patient in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2007; 25(7):1–13.

10. Myers, GM, James, GD. Social support, anxiety, and support group participation in patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008; 23(4):160–167.

11. Sears, SF, et al, Effective management of ICD patients psychosocial issues and patient critical eventsJ Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. epublication at printing/ahead of print, 2009.

12. Sears, SF, et al, State-of-the-art. anxiety management of patient with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Stress Health. 2008; 24(3):239–248.

![]() 13. Shea, J, et al, Quality of life issues in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. driving, occupation, and recreation. AACN Clini Issues. 2004; 15(3):89–478.

13. Shea, J, et al, Quality of life issues in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. driving, occupation, and recreation. AACN Clini Issues. 2004; 15(3):89–478.

![]() 14. Stevenson, WG, et al. Clinical assessment and management of patients with implanted cardioverter-defibrillators presenting to nonelectrophysiologists. Circulation. 2004; 110:3866–3869.

14. Stevenson, WG, et al. Clinical assessment and management of patients with implanted cardioverter-defibrillators presenting to nonelectrophysiologists. Circulation. 2004; 110:3866–3869.

15. Thomas, SA, et al. Quality of life and psychological status of patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Am J Crit Care. 2006; 15(4):389–398.

16. Trupp, RJ, Bubien, RS. Care of patients with implanted cardiac rhythm management devices. In: Moser DK, Riegel B, eds. Cardiac nursing: a companion to Braunwald’s heart disease. St Louis: Elsevier, 2008.

![]() 17. Wathen, MS, et al, Prospective randomized multicenter trial of empirical antitachycardia pacing versus shocks for spontaneous rapid ventricular tachycardia in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Pacing Fast Ventricular Tachycardia Reduces Shock Therapies (PainFREE Rx II) trial results. Circulation. 2004; 110(17):2591–2596.

17. Wathen, MS, et al, Prospective randomized multicenter trial of empirical antitachycardia pacing versus shocks for spontaneous rapid ventricular tachycardia in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Pacing Fast Ventricular Tachycardia Reduces Shock Therapies (PainFREE Rx II) trial results. Circulation. 2004; 110(17):2591–2596.

18. Wiegand, DL, Kalowes, P. Withdrawal of cardiac medications and devices. AACN Adv Criti Care. 2007; 18(4):415–425.

19. Wilkoff, BL, et al, HRS/EHRA expert consensus on the monitoring of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIEDs). description of techniques, indications, personnel, frequency and ethical considerations. Heart Rhythm. 2008; 5(6)

Abraham, WT, et al, for the MIRACLE Study Group. Cardiac resynchronization in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:1845–1853.

Bardy, GH, Lee, KL, Mark, DB, et al, for the Sudden Death -in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT) investigators. -Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:225–237.

Bristow, MR, Saxon, LA, Boehmer, J, et al, Comparison of Medical Therapy, Pacing, and Defibrillation in Heart -Failure (COMPANION) investigators. cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004; 350(21):2140–2150.

Buxton, AE, et al, for the Multicenter Unsustained Tachycardia Trial investigators. a randomized study of the prevention of sudden death in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 1999; 341:1882–1890.

Gura, MT, et al. North American Society of Pacing and -Electrophysiology standards of professional practice for the allied professional in pacing and electrophysiology. PACE. 2003; 26:127–131.

Kadish, A, Dyer, A, et al. Prophylactic defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2004; 350:2151–2158.

Moss, AJ, Zareba, W, et al. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:877–883.

Moss, AJ, et al, Improved survival with an implanted defibrillator in patients with coronary disease at high risk for -ventricular tachydysrhthmia. Multicenter Automatic -Defibrillator Implantation Trial investigators. N Engl J Med 1996; 335:1933–1940.

Mushlin, A, Jackson Hall WJ, Zwanziger, J, et al, the -MADIT investigators. The cost-effectiveness of automatic implantable cardiac defibrillatorsresults from MADIT. Circulation 1998; 97:2129–2135.

Sears, SF, et al. Quality of death and ICDs. PACE. 2006; 29:637–642.

St John Sutton MG, et al. Effect of cardiac resynchronization therapy on left ventricular size and function in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2003; 107(15):1985–1990.

Young, JB, Abraham, WT, Smith, AL, et al, Combined cardiac resynchronization and implantable cardioversion defibrillation in advanced chronic heart failure. the MIRACLE ICD trial. JAMA 2003; 289:2685–2694.

Wingate, S, Wiegand, D. End of life care in the critical care unit for patients with heart failure. Crit Care Nurse. 2008; 28(2):84–96.