CHAPTER 5. Moral problems and moral decision-making in nursing and health care contexts

L earning objectives

▪ Discuss the three distinguishing features of a moral problem.

▪ Explain why moral problems are different from other kinds of (non-moral) problems.

▪ Discuss the nature of the moral problems listed below and their possible implications in regard to the ethical practice of nursing:

• moral unpreparedness

• moral blindness

• moral indifference

• amoralism

• immoralism

• moral complacency

• moral fanaticism

• moral disagreement

• moral dilemmas

• moral stress, moral distress and moral perplexity.

▪ Define moral decision-making.

▪ Discuss critically the role that reason, emotion, intuition and life experience might play in moral decision-making.

▪ Discuss processes for dealing effectively with moral disputes.

▪ Explore a range of ‘everyday’ ethical issues that nurses might face in the course of providing nursing care to patients.

I ntroduction

A problem (from Late Latin problēma, meaning something that has been put forward or thrown forward) may be defined as ‘any thing, matter, person, etc, that is difficult to deal with, solve or overcome’ and as a puzzle or question that stands in need of a solution ( Collins Australian Dictionary 2005). A moral problem may be similarly defined, that is, as a moral matter or issue that is difficult to deal with, solve or overcome and which stands in need of a (moral) solution.

Nurses at all levels and in all areas of practice encounter moral problems during the course of their everyday professional practice. These problems range from the relatively ‘simple’ to the extraordinarily complex, and can cause varying degrees of perplexity and distress in those who encounter them. Whereas some moral problems may be relatively easy to resolve and may cause little if any distress to those involved, other problems may be extremely difficult or even impossible to resolve, and may cause a great deal of moral stress and distress for those encountering them.

Nurses, like other health professionals, have a stringent moral responsibility to be able to identify and respond effectively to the moral problems they encounter (whether ‘simple’ or ‘complex’), and, where able, to employ strategies to prevent them from occurring in the first place. In order to be able to do this, however, nurses must first be able to distinguish moral problems from other sorts of (non-moral) problems (e.g. legal and clinical problems), and to be able to distinguish different types of moral problems from each other. It is to advancing knowledge and understanding of the different kinds of moral problems that nurses might encounter in the course of their day-to-day practice — and how best to deal with them — that provides the focus for this chapter.

D istinguishing moral problems from other sorts of problems

All health professionals encounter a variety of problems in the course of their everyday practice, and nurses are no exception. Significantly, most of these problems probably have a moral dimension to them. It is important to clarify, however, that not all problems that have a moral dimension are moral problems per se. This raises the question: How are we to distinguish a bona fide moral problem from other kinds of (non-moral) problems? One clue to answering this question lies in the degree to which the moral dimension of a given problem might be deemed ‘weightier’ and thus prima facie as ‘overriding’ of the other dimensions of the problem, and the kinds of solutions that might be fruitfully employed to resolve the problem. Consider the following example.

A patient is in severe and intolerable pain due to not receiving pain medication. Nevertheless, while this is a problem and one which clearly has a moral dimension, it is not immediately evident that the problem is a ‘full-blown’ moral problem per se requiring moral analysis, debate and possibly the intervention of an ‘ethics expert’ or clinical ethics committee. Further analysis is required. It might be, for instance, that the patient’s pain management has, for some reason, been neglected. What is required in this instance is a competent and compassionate clinical assessment of the patient and the swift administration of needed analgesia. The problem may thus be correctly characterised as a ‘technical or practical problem’ requiring, and resolvable by, a ‘clinical solution’. It might also be, however, that the patient is in pain due to her refusing pain relief on religious grounds. In such an instance even the most competent and compassionate of clinical assessments will not necessarily result in the identification of a satisfactory solution to the problem of the patient’s pain since the obvious ‘clinical solution’ (i.e. of giving analgesia) is precluded by the moral demand to respect the patient’s autonomous wishes. The problem may thus be correctly characterised as a moral problem (not merely a clinical problem) since:

▪ the patient’s moral interest and wellbeing are at risk (if her autonomous wishes are respected, she will suffer the harm of intolerable pain; conversely, if her pain is alleviated by the administration of analgesia, she will suffer the harm of having her autonomous wishes violated)

▪ the nurses’ moral interests and wellbeing are at risk on account of the moral distress they experience at their genuine inability to maximise the patient’s moral interests in not suffering unnecessarily; and, finally,

▪ assistance is required to help attendant nurses to answer the question: What should we do?

To help clarify the basis upon which the above distinction has been made, the following framework is offered. It is generally accepted that something involves a (human) moral/ethical problem where it has as its central concern:

▪ the promotion and protection of people’s genuine wellbeing and welfare (including their interests in not suffering unnecessarily)

▪ responding justly to the genuine needs and significant interests of different people

▪ determining and justifying what constitutes right and wrong conduct in a given situation (Beauchamp & Childress 2001; Amato 1990; Frankena 1973).

The nursing profession is fundamentally concerned with the promotion and protection of people’s genuine wellbeing and welfare, and in achieving these ends, responding justly to the genuine needs and significant moral interests of different people. The nursing profession is, therefore, fundamentally concerned with ‘moral problems’ as well as other kinds of problems (e.g. technical, clinical, legal, and so forth).

In order to deal with moral problems appropriately and effectively it is evident that nurses need to know, first, what form a moral problem might take and how to recognise it; and, second, how best to decide when dealing with them. It is to answering these questions that this discussion now turns.

I dentifying different kinds of moral problems

The nursing literature has, to date, tended to focus predominantly on one type of moral problem; namely, the moral dilemma (also referred to as an ethical dilemma). While it is true that the moral/ethical dilemma is an important moral problem in nursing and health care domains, it needs to be clarified that it is by no means the only moral problem nurses (or others) will encounter when planning and implementing care. Indeed, there are at least ten different kinds of moral problems that can and do arise in nursing and health care contexts; these are:

If nurses are to respond effectively to the moral problems encountered in nursing and health care contexts, it is important that they understand the nature and implications of the different kinds of moral problems that can arise. It is to examining this issue further that the following discussion now turns.

M oral unpreparedness

The first type of moral problem to be considered here is that of general ‘unpreparedness’ to deal appropriately and effectively with morally troubling situations. What invariably happens here is that a nurse (or other health professional) enters into a situation without being sufficiently prepared to deal with the moral complexities of that situation specifically. The nurse (or other health professional) may lack the requisite moral knowledge, moral imagination, moral experience and moral wisdom otherwise necessary to be able to deal with the moral complexities of the situation at hand (this could also count as moral incompetence or moral impairment). When eventually faced with a particular moral problem, the nurse acts in bad faith by pretending that the situation at hand is one which can be handled ‘with one’s given moral apparatus’ (Lemmon 1987: 112). The room for moral error here is considerable.

To illustrate the seriousness of moral unpreparedness, consider the analogous situation of clinical unpreparedness. A nurse who is not educated in the complexities of, say, intensive care nursing, but who is nevertheless sent to ‘help out’ and care for a ventilated patient in intensive care, would not only be inadequate in this role, but could even be dangerous. Such a nurse might not have the learned skills necessary to detect the subtle changes in a sedated patient’s condition — changes indicating, for example, the need for more sedation, or the need to perform tracheal suctioning, or the need to increase the tidal volume of air flow or oxygen administration. Neither might this nurse be able to distinguish the many different alarms that can go off on the high-tech equipment being used to give full life support to the patient, or to detect any malfunctioning of this sophisticated equipment. Without these skills, a nurse working in intensive care would be likely to place the life and wellbeing of the patient at serious risk.

The argument of the seriousness of unpreparedness also applies to the complexities of sound ethical reasoning and ethical health care practice generally. Such a nurse, left to deal with a morally troubling situation, would not only be inadequate in that role but, as the intensive care example shows, his or her practice could be potentially hazardous. Without the learned moral skills necessary to detect moral problems and to resolve them in a sound, reliable and defensible manner, an unprepared nurse, no matter how well intentioned, could fail to correctly detect moral hazards in the workplace, and therefore fail to act or respond in a way that would prevent adverse moral outcomes from occurring.

The kinds of preventable adverse moral outcomes or ‘near misses’ that can occur as a result of nurses’ (and other allied health professionals’) moral unpreparedness to deal appropriately and effectively with moral problems in health care contexts are well documented in the nursing, bioethical, legal and other related literature. To give just one example, consider the notorious case of the Chelmsford Private Hospital in Sydney, Australia. In this case, many people were left permanently damaged and scarred — some even died — as a result of receiving deep sleep therapy (DST) prescribed by Dr Harry Bailey, a consultant psychiatrist, who later suicided in connection with the scandal that was eventually uncovered (Bromberger & Fife-Yeomans 1991; Rice 1988). It is now known that approximately one thousand patients were ‘treated’ with DST at this hospital. It is also known, as revealed as early as 1977 by the current affairs television program 60 Minutes, that many of these patients did not receive the standard of care and treatment they were entitled to receive. Among other things — including the deaths of seven people between 1974 and 1977 — the 60 Minutes program revealed that ‘recognised standard precautions for the safety of patients were not taken; and that patients received the treatment without their consent’ (Bromberger & Fife-Yeomans 1991: 142). In the Chelmsford Royal Commission that was eventually established in 1988 to ‘examine the provision of Deep Sleep Therapy and the administration of Chelmsford Private Hospital’, it was confirmed that:

The signature of some [consent] forms were obtained by fraud and deceit. Some were signed by people whose judgment was compromised by drugs. Some patients were even woken up from their DST [Deep Sleep Therapy] treatment to complete their authorisation. Other patients were treated contrary to their express wishes and some were treated despite the fact they had specifically refused the treatment.

(Commissioner Slattery, cited in Bromberger & Fife-Yeomans 1991: 171)

Nursing care was also seriously substandard. In one notable case, the nursing care had been so negligent that a patient developed severe decubitus ulcers between her knees, which became ‘glued’ together as though they had been skin-grafted. The former patient recalled:

I was having hallucinations about a lot of coloured ribbons and trying to climb out through them finding the world again. I woke up in a bath tub and two nurses were bathing me. I felt really dirty. One of the nurses said, ‘My God, look at her knees.’ I looked down and they were joined together. The nurses gently pulled them apart.

(Bromberger and Fife-Yeomans 1991: 94)

Bromberger and Fife-Yeomans (1991: 94) comment that the patient ‘still retains the scars on the inside of her knees’.

Another example of the substandard nursing care that was provided (or more to the point, not provided) can be found in the experiences of another patient, Barry Hart, outlined in the following statement read to the New South Wales Parliament in 1984:

Basic, commonsense nursing practice was ignored. Patients were sedated for ten days and given no exercise during this period. They were incontinent of faeces and urine most of the time and were left lying incontinent of faeces until they woke up.

There was no attempt to maintain a fluid balance. Patients wet the bed and remained lying in the urine until the sheets were changed. The staff made an approximation of whether the patients were actually passing urine (i.e. a fluid output) by seeing how wet the bed was.

(cited in Rice 1988: 47)

One of the troubling things about the whole Chelmsford scandal is that rumours about Dr Bailey’s unscrupulous practices had been circulating for years, yet nothing was done about it (Bromberger & Fife-Yeomans 1991: 176). Equally disturbing is the fact that it was not until 1988 — 24 years after the investigated death of the first ‘deep sleep’ patient, and only after ‘treatment’ had led to the deaths of 24 patients — that a Royal Commission was set up to investigate the allegations concerning the patient abuse that was subsequently proved to have occurred at Chelmsford Private Hospital (Bromberger & Fife-Yeomans 1991: 162). Significantly, in the Royal Commission of Inquiry that was conducted, and in the report on its findings, it was revealed that between 1963 and 1979 only two nurses took action in an attempt to expose the unscrupulous practices they had observed ( Report of the Royal Commission into Deep Sleep Therapy 1990: 127). There is room to speculate here that had nursing personnel been better prepared to recognise and respond effectively to violations of professional ethical standards, the trauma and suffering experienced by the patients at Chelmsford could have been reduced considerably, if not avoided altogether.

Not all adverse moral outcomes occurring in health care contexts are as ethically dramatic as those that occurred in the Chelmsford Private Hospital case, however. Preventable adverse moral outcomes can and do occur on a much more commonplace level in the health care arena, as examples to be given in the following chapters of this book will show.

M oral blindness

A second type of problem that nurses often encounter is that of what I shall call ‘moral blindness’. A morally blind nurse (or other health professional) is someone who, upon encountering a moral problem, simply does not see it as a moral problem. Instead, they may perceive it as either a clinical or a technical problem. A tendency by health professionals to sometimes ‘translate ethical issues into technical problems which have clinical solutions’ was recognised over three decades ago (Carlton 1978: 10), and persists in various forms to this day (the surgery ban on smokers, to be considered shortly in this section, is an example).

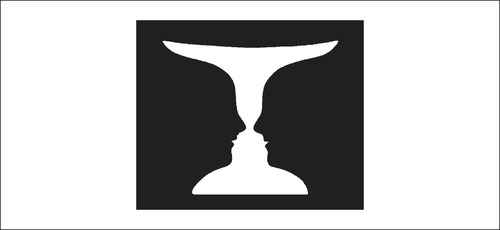

Moral blindness can be likened, in an analogous way, to colour blindness. Just as a colour-blind person fails to distinguish certain colours in the world, a morally blind person fails to distinguish certain ‘moral properties’ in the world. Perhaps a better example can be found by appealing to a set of imageries commonly associated with Gestalt psychology and theories on the nature of perception. What I particularly have in mind here are the two drawings which are popularly presented in psychology texts to demonstrate certain perceptual phenomena, including perceptual organisation and the influence of context on the way in which an object is perceived.

The first of these drawings (Figure 5.1) depicts what initially appears to be a white vase or goblet against a black background; after a more sustained glance, the drawing changes (or rather, one’s perception ‘shifts’) and what is perceived instead are two black facial profiles separated by a white space. Some people see the alternating vase–face images relatively quickly and easily, while others struggle to shake off what for them remains the dominant image (i.e. either the vase or the faces).

|

| Figure 5.1

(reproduced with permission from Atkinson R L, Atkinson R C & Hilgard E R [1983] Introduction to psychology, 8th edn. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York, p 139)

|

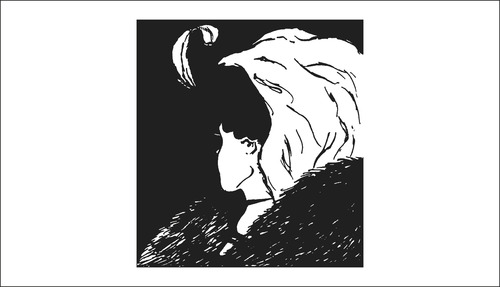

The second ambiguous drawing (Figure 5.2) depicts what can be seen as either an unsophisticated-looking old woman or a very sophisticated-looking young woman. As with the vase–face drawing, some people see the alternating old woman–young woman images relatively easily, while others literally get ‘stuck’ with a dominant perception of either the young woman or the old woman.

|

| Figure 5.2

(reproduced with permission from Atkinson R L, Atkinson R C & Hilgard E R (1983) Introduction to psychology, 8th edn. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York, p 139)

|

Psychologists claim, however, that people’s perceptions can be altered by context — in this instance, by showing photographs before the ambiguous drawings are viewed. They claim that, on an initial viewing of the second drawing, 65 per cent report seeing the young woman first. If subjects are shown photographs of an old woman before seeing the drawing, however, almost all see the old woman first. The same ‘reversals’ can be achieved by conditioning subjects with photographs to see the young woman first (Atkinson et al 1983: 147).

I am not here attempting to present an elaborate theory of moral perception but rather trying to illustrate what I believe is a common and potentially morally risky phenomenon in health care contexts: that of impaired moral perception. There is, I think, room to suggest that health professionals (including nurses) are sometimes so conditioned by the ‘clinical imagery’ (context) around them that, when they do encounter a bona fide moral problem, it tends to be perceived not as a moral problem, but as a clinical or a technical problem and, as such, one requiring a clinical solution, not a moral solution. Some health professionals have a healthy perception of the alternating moral–clinical images depicted by a given scenario; others, however, remain stuck with a dominant clinical image and do not see the alternative moral image, which for them is less discernible. One unfortunate consequence of this, is that technically correct decisions are sometimes made at the expense of morally correct decisions.

The extent to which clinical perceptions and judgments can dominate over moral perceptions and judgments can be illustrated by the once common practice of defending ‘Do Not Resuscitate’ (DNR) directives (also called ‘Not For Resuscitation’ or NFR directives) on hopelessly or chronically ill patients on medical grounds (‘medical indications’) alone. In the past many doctors and nurses perceived DNR directives as involving a clinical issue, not a moral issue, and, as such, one to be decided by doctors, not ethicists. The clinical–moral Gestalt problem became particularly clear to me at a nursing law and ethics conference in 1988. After presenting a paper on the nature and moral implications of DNR/NFR directives, I was approached by several registered nurses with what became a familiar and distressing comment: ‘My God! I had never thought about it [DNR/NFR] as a moral issue before … What have I done?’; other nurses wanted to challenge or attack the view that DNR/NFR directives involved moral considerations and moral decisions. The then state president (in Victoria) of the Australian Medical Association, Dr Bill McCubbery, was prompted to respond to the issue, and is reported as saying that ‘NFR decisions had to depend on professional judgment’ (Schumpeter 1988: 21).

Today there is a much greater recognition of the moral dimensions of DNR/NFR directives and the degree to which such directives are informed by moral considerations (see the discussion on DNR in Chapter 12 of this book). The once common view that DNR/NFR decisions are based ‘simply’ on medical concerns/indications (not ethical concerns) and are more a matter of ‘good medical judgment’ (rather than — or as well as — sound moral judgment) is rarely advanced in contemporary debate, at least not credibly. Nevertheless, this kind of thinking persists in regard to other issues. For example, in 2001, in a highly publicised surgery ban imposed on smokers by doctors in the Australian state of Victoria, surgeons were reported as defending their stance by arguing that:

Medical concerns, not moral judgments, were the bottom line in banning smokers from a range of life-saving treatments. [emphasis added]

(Chandler 2001)

The specific treatments banned, in this instance, were reported to include: artery by-passes, coronary artery grafts, lung reduction surgery and lung and heart transplants (Taylor 2001: 4). In 2004 and 2007 respectively, surgeons again defended their ‘right’ to refuse to operate on people who smoked cigarettes (Peters 2007; Peters et al 2004; see also rejoinder by Glantz 2007).

The issue of ‘moral blindness’ among nurses is an important one, since, as with the problem of moral unpreparedness, it could result in otherwise avoidable moral harms occurring. This problem is not insurmountable, however. Just as people can be ‘conditioned’ to see the old woman rather than the young woman in the ambiguous drawing shown in Figure 5.2, so too can nurses and allied health professionals be ‘conditioned’ (or rather educated) to see the moral dimension of an ambiguous scenario which can be perceived as involving either a moral problem or a clinical or technical problem. Arguably, the best way to achieve such a Gestalt moral shift in perception is by appropriate ethics education and reflective ethical practice.

M oral indifference

A third type of problem which nurses may encounter is that of ‘moral indifference’. Moral indifference is characterised by an unconcerned or uninterested attitude towards demands to be moral; in short, it assumes the attitude of: ‘Why bother to be moral?’ The morally indifferent person is someone who typically refrains from expressing any desire that certain acts should or should not be done in all comparable circumstances (Hare 1981: 185). An example of a morally indifferent nurse would be a nurse who is both unconcerned about and uninterested in alleviating a patient’s pain, or is unconcerned about or uninterested in the fact that a DNR directive or a directive to perform electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been given on an unconsenting patient, or is unconcerned about and uninterested in any form of violation of patients’ rights, for that matter. As well as this, a morally indifferent nurse would probably refrain from expressing a desire that anything should be done about such situations.

The problem of moral indifference in nursing is well captured by Mila Aroskar (1986) in her classic article ‘Are nurses’ mind sets compatible with ethical practice?’. Aroskar (1986: 72) cites the findings of a study undertaken in the late 1970s which showed that nurses tended to defer to institutional norms ‘even when patients’ rights were being violated’. She also points out that, despite the North American nursing profession’s formal commitment to ethical practice (as manifested, among other things, by its formal adoption of various codes and standards of practice), arguments were still widely heard among nurses that ‘ethical practice is too risky and requires a certain amount of heroism on the part of nurses’ (Aroskar 1986: 69). Although written almost two decades ago, Aroskar’s words still apply today. As Jill Iliffe of the Australian Nursing Federation reflects (2002: 1):

What do you do when something happens that you know to be wrong, unethical or inappropriate? […] A colleague behaves unprofessionally; health care is provided that you know to be inappropriate; a decision is made that is ethically questionable; there is an adverse outcome that could have been avoided, or was perhaps even the result of negligence. What do you do? It is often a difficult decision to make, particularly when the other person or persons are more senior to you and in a position of power and authority.

The retreat by nurses into moral indifference, while not condonable, is understandable. There are many examples that demonstrate the kinds of difficulties nurses might find themselves in when attempting to conduct morally responsible, professional practice, and the ultimate price that can be paid for taking a moral stand on a matter. One such example concerns the highly publicised United Kingdom case of a registered nurse by the name of Graham Pink. Pink was found guilty of ‘gross misconduct’ by his employing health authority after he publicly exposed unacceptable standards of care (including poor staff–patient ratios) in the hospital at which he worked (Turner 1992, 1990; Tadd 1991). Pink’s ordeal began in 1989 when he wrote to the local health authority detailing his concerns about the substandard care that was being given to elderly residents at the hospital where he worked. The health authority followed up the complaint and agreed that ‘something must be done’ and instructed the hospital ‘to look at’ staffing levels (Turner 1992: 28). When these instructions were not actioned, Pink communicated his concerns in writing to the chief executive of the National Health Service, the health secretary and the prime minister Mrs Thatcher. He received a written reply from the latter two ‘thanking him’ for the information but pointing out that it was ‘a local matter’ (Turner 1992: 28).

Subsequently Pink was persuaded by a member of parliament to allow a selection of his letters to be published in the Guardian newspaper. This action resulted in enormous public support. Pink, meanwhile, was warned ‘not to speak out further’ (Turner 1992: 28). Even though his actions (‘to take appropriate action’) were supported by the United Kingdom Central Council’s Code of Professional Conduct (1984) and advisory document Exercising Accountability (1989) that were in operation at the time, they nevertheless placed him at odds with his employer. Pink was suspended from duty, and the hospital management initiated disciplinary procedures against him. After 1 year of hearings and appeals, Pink was found guilty of gross misconduct and offered a transfer to a community setting. Pink refused this offer, however, and was dismissed by his employer. Summing up the implications of this case, one nurse is reported as commenting: ‘It is difficult to imagine anybody ever speaking out again — they just wanted to get him and they did’ (Turner 1990: 19). Another commentator concludes succinctly: ‘Graham Pink’s experience show[s] that once nurses raise their heads above the parapet they may not be far from disciplinary action’ (Turner 1990: 19).

Although this case occurred several years ago, the lessons it provides remain current and are indicative of the difficulties nurses worldwide often face when trying to deliver ethically responsible care (see also Chapter 13 of this book). We all know (and have possibly personally experienced) the forces that can be brought to bear upon a nurse who takes a moral position which conflicts with established hospital norms and etiquette. It is then perhaps understandable (even though not excusable) that nurses become morally indifferent to the violations of patients’ rights and other unjust practices in health care domains. Compounding this situation, institutional and legal constraints may make it very difficult for nurses to act morally (Johnstone 2002a, 1994). The price paid for acting morally or for taking a moral stand can be intolerably high, as other examples to be given in the chapters to follow will show. What this signifies, however, is not that nurses should abandon the demands of morality; rather, they should seek ways in which morality’s demands can be upheld safely and effectively.

A moralism

A fourth type of moral problem which nurses might encounter, and which is similar to moral indifference, is that of ‘amoralism’, which is characterised by an absence of moral concern and a rejection of morality altogether (a position significantly different from immoralism, [discussed below] which accepts morality, but violates its demands). An amoral person is someone who refrains from making moral judgments and who typically rejects being bound by any of morality’s behavioural prescriptions and proscriptions. If an amoralist were to ask: ‘Why should I be moral?’, it is likely that no answer would be satisfactory. (For a classic response to the question: ‘Why should I be moral?’, see Nielsen 1989.)

A nurse who is an amoralist would reject any imperative to behave morally as a professional. For example, the amoral nurse might reject that he or she has a moral duty to uphold a patient’s rights. The amoral nurse would also probably claim that it does not make any sense even to speak of things like a patients’ ‘rights’ since moral language itself has no meaning. The amoralist’s position in this respect is analogous to the atheist’s rejection of certain religious terms. The extreme atheist, for example, would argue against uttering the word ‘God’, since it refers to nothing and therefore has no meaning. Such an atheist might also claim that there is no point in engaging in a religious debate on the existence of God, since there is just nothing there to debate. To try and debate the existence of God would be like trying to debate the existence of ‘a black cat in a darkened room when there isn’t one’. The amoralist may argue in a similar way in relation to the issue of morality.

It can be seen that the amoralist’s position is an extreme one, and one which is very difficult to sustain. (Even thieves, who may appear amoral, act on the ‘moral’ assumption that it is ‘good/right’ to steal.) Perhaps the most approximate example that can be given here is that of psychopaths or frontal lobe damaged persons who simply lack all capacity to be moral — an issue that has been comprehensively explored in the neuroethics literature (see, for example, Damasio 1994, 2007; Gellene 2007; Koenigs et al 2007; Strueber et al 2007). If amoralism is encountered in health care contexts, it is likely that very little can be done, morally speaking, to deal with it. The only recourse in dealing with the amoral health professional would be to appeal to non-moral censuring mechanisms such as legal and/or professional disciplinary measures.

I mmoralism1

At its most basic, immoral conduct (also known as moral turpitude and moral delinquency) can be defined as any act involving a deliberate violation of accepted or agreed ethical standards. Moral turpitude (a notion which has received more stringent attention in the United States than in Australia) has been defined specifically as:

anything done knowingly contrary to justice, honesty, principle, or good morals … [or] an act of baseness, vileness or depravity in the private or social duties which a man [sic] owes to his fellow man [sic] or to society in general. The term implies something immoral in itself.

( Seary v State Bar of Texas, cited in Freckelton 1996: 142)

Moral delinquency, in turn, is taken here as referring to any act involving moral negligence or a dereliction of moral duty. As in the above definitions, moral delinquency in professional contexts entails a deliberate or careless violation of agreed standards of ethical professional conduct.

Accepting the above account, an immoral nurse can thus be described as someone who knowingly and wilfully violates the agreed norms of ethical professional conduct or general ethical standards of conduct towards others. Judging immoral conduct, by this view, would require a demonstration that the accepted ethical standards of the profession were (1) known by an offending nurse, and (2) deliberately and recklessly violated by that nurse. There are many ‘obvious’ examples of immoral conduct by nurses. These include: the deliberate theft of patients’ and/or clients’ money for personal use; the sexual, verbal and physical abuse of patients/clients; xenophobic behaviours (including racism, sexism, ageism, homophobia and a range of other unjust discriminatory behaviours); participation in unscrupulous research practices; and other morally unacceptable behaviours, examples of which are given throughout this book.

It should be noted that regardless of whether an act involving the violation of agreed professional or general ethical standards results in a significant moral harm to another, it would still stand as an instance of immoral conduct. For example, a nurse who knowingly and recklessly breaches a patient’s/client’s confidentiality would have committed an unethical act even if the breach in question did not result in any significant moral harm to the patient/client.

M oral complacency

A sixth type of moral problem nurses can encounter is that of ‘moral complacency’, defined by Unwin (1985: 205) as ‘a general unwillingness to accept that one’s moral opinions may be mistaken’. It could also be described as a general unwillingness to ‘let go’ the primacy of one’s own point of view or to regard one’s own point of view as just one of many to be compared, contrasted and considered. Again, we do not need to look far to find examples of moral complacency in health care contexts.

I recall, several years ago, once being approached by a then gerontology clinical nurse specialist lamenting the ‘short-sightedness’ of some of her students, who were of the view that elderly people in residential care homes should be resuscitated in the event of cardiac arrest, and that the blanket DNR status that was automatically given to all elderly residents upon entering a residential care home was both immoral and illegal. The nurse specialist was insistent that the students were morally wrong, and was clearly disturbed and outraged by their position.

In my response to her, I inquired concerning the discussion she had with her students whether anyone had thought to ask the elderly residents what their preferences were — whether, in the event of cardiac arrest, they wished to be resuscitated or not? It should be noted that, at that time, elderly people entering a residential care agency were invariably asked whether upon their death they wished to be cremated, or where they wished to be buried; they were not always asked, however, whether they wished to be resuscitated in the event of a cardiac arrest. The nurse specialist became obviously agitated by my question, and exclaimed: ‘Surely it is ludicrous to ask all elderly residents whether they wish to be resuscitated!’ After I had expressed my disagreement and pointed out the minimal requirements of the moral principle of autonomy, the nurse specialist retorted: ‘Would you really expect us to ask each and every resident whether they wish to be resuscitated? It’s ludicrous! It’s silly! It’s unnecessary …’. To this retort, I reminded the nurse specialist that elderly residents are already asked whether they wish to be cremated or where they wish to be buried upon their death so what was so difficult about asking them whether they wish to be resuscitated? The nurse specialist was still unconvinced, and persisted in rejecting the view I was putting to her. She further maintained that it was right and proper that all elderly residents should be uniformly designated DNR upon admission to a residential nursing care home. The attitude of the nurse specialist in this anecdote is an example of moral complacency.

Like moral unpreparedness and moral blindness, moral complacency is something which can be rectified by moral education, moral consciousness raising, and reflective practice in an ethical environment. The objective of taking this action would be, of course, to produce in the morally complacent person the attitude that nobody can afford to be complacent in the way they ordinarily view the world — least of all the moral world. This is particularly so in instances where other people’s moral interests are at stake. It is a grave mistake to assume that our moral opinions are ‘right’ just because they are our own opinions. As ethical professionals, our stringent moral responsibility is to question our taken-for-granted assumptions about the world, and not to presume that they are always well founded and unable to be challenged.

M oral fanaticism

A seventh type of moral problem which may be encountered by nurses, and which is similar in many respects to moral complacency, is that of ‘moral fanaticism’. The moral fanatic is someone who is thoroughly ‘wedded to certain ideals’ and uncritically and unreflectingly makes moral judgments according to them (Hare 1981: 170). Richard Hare’s classic case of the fanatical Nazi is a good example here (Hare 1963: Chapter 9). The fanatical Nazi in this case stringently clings to the ideal of a pure Aryan German race and the need to exterminate all Jews as a means of purging the German race of its impurities. The Nazi falls into the category of being a ‘fanatic’ when he/she insists that, if any Nazis discover themselves to be of Jewish descent, then they too should be exterminated along with the rest of the Jews (Hare 1963: 161–2).

Examples of moral fanaticism exist in health care contexts. The surgeon who repeatedly performs ‘futile’ surgery in an attempt to prolong the life of a terminally ill patient, regardless of the dying patient’s wishes to the contrary and the suffering it causes, is an important example here. Morally fanatical doctors in this instance might defend their position by claiming that it is not only medically indicated but strongly warranted from a moral point of view. The maintenance of absolute confidentiality, even though harm might be caused as a result, is another good example. So, too, is the example of a doctor or a nurse forcing unwanted information on a patient in the fanatical belief that all patients must be told the truth — even if the patient in question has specifically requested not to receive the information, and the imposition of the unwanted information on the patient can be shown to be a ‘gratuitous and harmful misinterpretation of the moral foundations for respect for autonomy’ (Pellegrino 1992: 1735).

In the case of moral fanatics, an appeal to overriding considerations or principles of conduct would not be helpful (Hare 1981: 178). As with the amoralist, the problem of the moral fanatic in health care contexts is likely to have disappointing outcomes. In the final analysis, it may be that other (non-moral) mechanisms will have to be appealed to in order to resolve the moral problems caused by moral fanaticism; for example, it may be necessary to seek the involvement of a public advocate, a court of law or a disciplinary body to arbitrate the matter.

M oral disagreements and conflicts

An eighth type of moral problem nurses will very often encounter is that involving ‘moral disagreement’ — concerning, for example, the selection, interpretation, application and evaluation of moral standards. In his classic article ‘Moral deadlock’, Milo (1986) identifies two fundamental types of moral disagreement: internal moral disagreement and radical moral disagreement.

Internal moral disagreement

Three forms of internal moral disagreement can occur. The first of these involves a fundamental conflict about the force or priority of accepted moral standards. For example, two people may agree to common moral standards but disagree about what to do when these standards come into conflict. Milo (1986: 455) argues that the disagreement here is not necessarily attributable to ‘any disagreement in factual beliefs or to bad reasoning’, but to a disagreement in attitude (see also McNaughton 1988: 17, 29). Consider the following hypothetical example to illustrate Milo’s point.

Two nurses might both accept a moral standard which generally requires truth telling, but may disagree on when this standard should apply. Nurse A, for instance, might favour (i.e. have a ‘pro-attitude’ towards) telling the truth to patient X about a pessimistic medical diagnosis. Nurse B, on the other hand, might not favour (i.e. might have a ‘con-attitude’ towards) telling the truth to patient X about this diagnosis and prefer a pro-attitude to avoiding unnecessary suffering (e.g. as a result of a nocebo effect [see Chapter 4] that might be inadvertently stimulated in the patient upon his learning about the diagnosis). It is not that these two nurses have different criteria of relevance, as such, but rather have different principles of priority (Milo 1986: 457).

A second type of internal disagreement centres on what are to count as acceptable exceptions and limitations to otherwise mutually agreed moral standards. As Milo explains, we generally accept that moral standards are limited by other moral standards, as well as by the competing claims of self-interest. (Morality does not usually expect us to risk our own lives or our own important moral interest in morally troubling situations.) People might agree that as a general rule we should all make certain modest sacrifices in terms of our own interests (a minimal requirement of justice), but may disagree ‘about what constitutes a modest sacrifice’ (Milo 1986: 459). In many respects this type of disagreement could be loosely described as a disagreement in interpretation of an accepted moral standard. Consider another example.

Two nurses might agree that patients’ rights should not be violated. Nurse A might further hold that, in situations involving violations of patients’ rights, a nurse should act — even if this means threatening the nurse’s job security (which Nurse A views as a modest sacrifice). Nurse B, on the other hand, might agree that nurses should in principle act to prevent a patient’s rights from being violated, but disagree that nurses should do so if they stand to lose their jobs as a result (something which Nurse B views as an unacceptable and extreme sacrifice). What these two nurses are essentially disagreeing about is not the moral standard per se (that nurses should act to prevent violations of patients’ rights), but about when morally relevant considerations can be and cannot be overridden by self-interest. In disagreements like this, and where the disagreement is based on preferences rather than attitude, there may well be no happy solution, a situation which Milo calls a ‘moral deadlock’ (1986: 461).

A third and final type of internal moral disagreement centres on the selection and applicability of accepted ethical standards. This kind of disagreement has nothing to do with whether a standard can be overridden by other considerations, but concerns whether it should have been selected or appealed to in the first place.

For example, two nurses may agree that killing an innocent human being is wrong. They may disagree, however, that abortion is wrong. Nurse A, for example, might argue that, since the fetus is not a human being, abortion does not entail the killing of an innocent human being and therefore is not wrong. Appealing to a moral standard prohibiting the killing of innocent human life would then, for Nurse A, be quite irrelevant. Nurse B, on the other hand, may argue that the fetus is a human being, and therefore abortion, since it entails killing an innocent human being, is absolutely morally wrong. Appealing to a moral standard prohibiting the killing of innocent human life would then, for Nurse B, be supremely relevant. The disagreement between these two nurses hinges very much on a disagreement about the moral relevance of the facts on what constitutes a human being.

Radical moral disagreement

Milo (1986) identifies two types of radical moral disagreement: the first type he calls ‘partial radical moral disagreement’, and the second type ‘total radical moral disagreement’.

In cases of partial radical moral disagreement, dissenting parties might agree on some criteria of relevance but not all. For example, a nurse might argue that directly killing terminally and chronically ill patients with a lethal injection is morally wrong, whereas merely ‘letting nature take its course’ or ‘letting patients die’ is not morally wrong. Another nurse might agree that directly killing terminally and chronically ill patients is wrong, but thoroughly disagree that merely ‘letting patients die’ is less morally offensive. Here there may be no court of appeal to reconcile the distinction between direct ‘killing’ and merely ‘letting die’. In this case, partial radical disagreement is very similar to internal moral disagreement. It may be very difficult to distinguish between the two, a point which Milo reluctantly concedes.

In cases of total radical moral disagreement, disputants do not agree on any criteria of relevance, and do not share any basic moral principles. For Milo (1986: 469), this is ‘the most extreme kind of moral disagreement that one can imagine’.

An example of total radical moral disagreement would be where two theatre nurses radically disagree with each other about the moral acceptability of organ transplantations. Nurse A argues that retrieving or harvesting organs from so-called ‘cadavers’ is an unmitigated act of murder, since the person whose organs are being retrieved is not yet fully dead. (Nurse A, in this instance, rejects brain-death criteria as indicative of death.) Nurse A also argues that, even if the potential cadaver is restored to nothing more than a persistent vegetative state, and even if another person may die as a result of not getting a life-saving organ transplant operation, this does not justify violating the sanctity of life of the potential organ donor. The death of another person through not receiving a new organ, while ‘unfortunate’, cannot be helped. Such are the tragic twists of life.

Nurse B, on the other hand, argues that retrieving organs is nothing like murder since, among other things, the person is already dead. (Nurse B, in this instance, totally accepts brain-death criteria as indicative of death.) Nurse B also totally rejects a ‘sanctity of life’ view, arguing that it has no substance; only quality-of-life considerations have ethical meaning. Nurse B further argues that, even conceding the unreliability of brain-death criteria as indicative of death, retrieving the organs is still morally permissible, since the donating person can at best look forward only to a ‘vegetative existence’ and one devoid of any ‘quality of life’ (which is cruel and immoral), whereas an organ recipient could look forward to a renewed quality of life and indeed to life itself.

In the dispute between Nurse A and Nurse B, resolution is unlikely. As Milo points out, in total radical disagreement the disputants reach a total and irreconcilable impasse. The possibility of this situation occurring in health care contexts is, I believe, something which needs to be taken very seriously, and which has important implications for conscientious objection claims (an issue that is given separate consideration in Chapter 13 of this book).

It should be clarified here that, while moral disagreements can certainly be problematic (particularly if a person’s life and wellbeing are hanging in the balance, and an immediate decision is needed about what should be done), these need not be taken as constituting grounds upon which morality as such should be viewed with scepticism or, worse, rejected altogether. As Stout (1988: 14) argues persuasively, the facts of moral disagreement ‘don’t compel us to become nihilists or sceptics, to abandon the notions of moral truth and justified moral belief’. One reason for this, he explains, is that moral disagreement is, in essence, just a kind of moral diversity or, as he calls it, ‘conceptual diversity’ (pp 15, 61). While moral disagreement may rightly challenge us to ‘meticulously disentangle’ diverse and conflicting moral points of view, it does not preclude or threaten the possibility of moral judgment per se, either within a particular culture or across many cultures (p 15).

As argued previously, moral disagreement has historically been the beginning of critical moral thinking, not its end. Given this, there is room to suggest that we should be very cautious in accepting Milo’s pessimistic conclusions about the irreconcilability of radical moral disagreement. Instead, we should look towards a more optimistic solution, and view such disagreements as an important and necessary opportunity for ‘enriching [our] conceptions of morality through comparative inquiry’ (Stout 1988: 70), and thereby augment our collective wisdom about what morality is, and what it really means to be moral in a world characterised by individual and collective (cultural) diversity. In the ultimate analysis, the solution to the problematic of moral disagreement may not be to engage in adversarial dialogue (fight/litigate), or even to negotiate a happy medium between conflicting views (compromise). Rather, the solution may be, to borrow from Edward de Bono (1985), to engage in ‘triangular thinking’; to engage in moral disagreement, not as a judge or as a negotiator, but as a ‘creative designer’ who is able to escape the imprisonment of the positivist logic and language that is so characteristic of mainstream Western moral discourse, and to engage in moral disagreement as someone who is able ultimately to resolve the conflicts and disagreements which others have long since abandoned as hopeless and irreconcilable impasses. Such an approach, however, requires not just an ability to think about new things, but, as Catharine MacKinnon (1987: 9) puts it, to engage in ‘a new way of thinking’. Possible approaches to dealing effectively with moral disagreements and disputes will be considered shortly in this chapter under the subheading ‘Dealing with moral disagreements and disputes’.

M oral dilemmas

Another significant moral problem to be considered here (and one which has been widely discussed in both nursing and bioethical literature) is that of the proverbial ‘moral dilemma’ (also called ‘ethical dilemma’). Broadly speaking, a dilemma may be defined as a situation requiring choice between what seem to be two equally desirable or undesirable alternatives; it may also be described as an ‘awful feeling of being stuck’. A moral dilemma, however, is a little different, and can occur in one of several forms.

First, a moral dilemma can occur in the form of logical incompatibility between two different moral principles. For example, two different moral principles might apply equally in a given situation, and neither principle can be chosen without violating the other. Even so, a choice has to be made. Consider the case of a nurse who accepts a moral principle which demands respect for the sanctity of life, and who also accepts another moral principle (non-maleficence) which demands that persons should be spared intolerable suffering. Now, imagine this nurse in the situation of caring for a seriously ill patient in the end stages of life and who is suffering intolerable and intractable pain. In this situation, if the nurse accepts the sanctity of life principle, the administration of the large and potentially lethal doses of narcotics that might be required to relieve the patient’s intolerable pain would probably be prohibited. On the other hand, if the principle of non-maleficence were followed, the nurse might be required to administer the potentially lethal doses of narcotics, even though this could hasten the patient’s death. In this situation, the nurse is unavoidably confronted with the profound and troubling dilemma that to uphold the sanctity-of-life principle could violate the principle of non-maleficence, and to uphold the principle of non-maleficence could violate the sanctity-of-life principle. The ultimate question posed for the nurse in this situation is: Which principle should I choose?

The options open to the nurse are:

▪ to modify the principles in question so that they do not conflict (i.e. by adding ‘riders’ to them)

▪ to abandon one principle in favour of the other

▪ to abandon both principles in favour of a third (e.g. autonomy and respect for the patient’s rational wishes, or the virtue of compassion).

It should be noted that none of these options is free of moral risk.

A second type of moral dilemma is that involving competing moral duties. Consider the following case. A nurse working in a specialised unit is assigned a patient with a known history of drug addiction, and is instructed to chaperone the patient when there are visitors to make sure that illicit drugs are not ‘slipped in’. The nurse, however, believes that the duty to protect this patient from harm (such as might occur from receiving illicit drugs) competes with the duty to respect the patient’s privacy. The question for the nurse in this scenario is: Which duty should I fulfil?

In another case, a nurse is assigned a patient of traditional Greek background who has recently been diagnosed with metastatic cancer. The doctor has ordered that the patient not be told his diagnosis. The patient, however, keeps asking the nurse and his family for information about his diagnosis. The family knows the diagnosis, but wants the doctor to tell the patient. Here the nurse is caught between a duty to tell the truth to the patient, and a duty to respect the wishes of the family. The nurse is also bound to follow the doctor’s directives (although the question of whether there is a duty to follow them is another matter). The question for the nurse in this scenario is, again: Which duty should I fulfil — my duty to the patient or to the family, or to the doctor, or to whom?

Philosophical answers to questions raised by a conflict of duty are varied and controversial. In the classic work The right and the good, Ross (1930) argues that duties are prima facie or ‘conditional’ in nature. Thus, when two duties conflict, we must ‘study the situation’ as fully as we can until we are able to reach a ‘considered opinion (it is never more) that in the circumstances one of them [the duties] is more incumbent than any other’ (p 19). Once we have worked out which of the conflicting duties is the more ‘incumbent’ on us, we are bound to consider it our prima-facie duty in that situation. Richard Hare (1981: 26), however, takes quite a different view. He argues that, if we find ourselves caught between what appear to be two conflicting duties, we need to look again. For it is likely that, in the case of an apparent conflict in duties, one of our so-called ‘duties’ is not our duty at all; we have only mistakenly thought that it was. In other words, what happens here is that one of the two apparently conflicting duties is eventually ‘cancelled out’, so to speak.

Williams (1973) disagrees. While he believes that one of the conflicting oughts has to be rejected (but only in the sense that both conflicting duties/oughts cannot be acted upon), he does not agree that this means that the duties or oughts in question do not apply equally in the situation at hand, or that one of the conflicting duties must inevitably be ‘cancelled out’. To the contrary: our reasoning may assist us to deal with a conflict of duty and may assist us to find a ‘best’ way to act, but this does not mean that we abandon one or other of the duties in question. How do we know? Even after making a choice between two conflicting duties, we are still left with a lingering feeling of ‘regret’. And it is this very feeling of regret which tells us that we have not altogether abandoned or ‘cancelled out’ the duty we decided could not, in that situation, be also acted upon.

In the drug addict case, we might well side with Richard Hare and unanimously agree that the nurse is mistaken in a belief that there is an overriding duty to respect the patient’s privacy, and that clearly the primary duty is to prevent the patient from suffering the harms likely to be incurred by the administration of illicit drugs. But here the question arises: Is it really a nurse’s duty to act as a kind of police warden? What if the patient is not receiving any form of therapy for the immediate drug addiction problem, and is at risk of developing severe and life-threatening withdrawal symptoms? How is the nurse’s duty to ‘prevent harm’ to be regarded in this instance? Does cancelling out one of the conflicting duties here relieve the moral tension created in this scenario? Or is there more to be achieved by exploring ways in which they can be reconciled with each other?

In the cancer diagnosis case, we might unanimously agree that the nurse’s primary duty is to the patient, and that any apparent duty owed to the family is not a bona fide one. (After all, does not the moral principle of autonomy demand respect for the patient’s rational wishes in this scenario?) Placed in a cultural context, however, the scenario takes on a whole new dimension. As was considered in Chapter 4 of this book, families from a traditional cultural background often play a fundamental and highly protective role in mediating the flow of information to a sick loved one. To ignore a family’s request in such a situation could be to risk terrible violence to the wellbeing of the patient. Where this is likely, it is imperative that the nurse works closely with the family and ensures that the transfer of information to the patient is handled in a culturally appropriate manner. While the family may be perceived as ‘interfering’, in reality it may be providing an important and key link in ensuring that the patient’s wellbeing and moral interests are fully upheld.

Cancelling out one of the duties in this scenario is unlikely to relieve the moral tension generated by the patient’s request for and the doctor’s refusal to give the medical information on the patient’s diagnosis. Had the only criterion for action been what superficially appeared to be a primary duty to the patient, the nurse may have unwittingly facilitated the flow of information in a culturally inappropriate and thus harmful manner. By reconciling the apparent conflict in duties, and by working closely with the family, however, the nurse is able to facilitate the flow of information to the patient in a culturally appropriate and thus less harmful manner. In this instance, by fulfilling the duty owed to the family, the nurse could also succeed in fulfilling the duty owed to the patient.

It might be objected that the examples given here do not involve difficult cases, and that the required choices are relatively easy to make. But even if we admit ‘hard cases’, Hare’s position is somehow unsatisfactory, as is his argument that when there is an apparent conflict in duties, it is likely that one of the duties involved is not our duty at all. There is always room to question how we can ever be really sure that a ‘cancelled’ duty was not our duty in the first place. The cancer diagnosis case, I think, illustrates this point well. Ross’s (1930) and Williams’ (1973) positions, on the other hand, remind us that matters of moral duty are never clear-cut; and, further, that we always have to be very careful in our appraisal of given situations and in the choices we make regarding to whom our moral duties are owed and what our moral duties actually are.

A third kind of moral dilemma, and one closely related to a dilemma concerning competing duties, is that entailing competing and conflicting interests. Here the question raised for the moral observer is: Whose interests ought I to uphold?

Consider the following case. A clinical teacher on clinical placement at a residential care home was informed by a student that an elderly demented resident had been physically and verbally abused by one of the ward’s permanent staff members, as witnessed by the student. The clinical teacher was temporarily undecided about what to do. It was a very serious matter — and, indeed, a very serious accusation — but it would be very difficult to prove. If the incident was not reported to the home’s nursing administrator, the staff member concerned would probably continue to abuse the home’s residents. If the incident was reported, there was a risk that the interests of both students and the school of nursing could be threatened. (The home’s administrator might, e.g. refuse to continue allowing students to be placed at the home for the purposes of gaining clinical experience.) The dilemma for the clinical teacher was whether or not to report the matter and thereby protect both the students’ and the school’s interests in having continued clinical placements, or to report the matter fully, whatever the consequences to the school and the students, and thereby protect the residents’ interests.

The teacher and the student mutually agreed that the matter was too serious to ignore and decided they would risk the consequences of reporting the incident. The exercise, as feared, proved extremely distressing and painful for both the student concerned and the clinical teacher. The accused staff member denied having abused the elderly resident, and in turn accused the student of lying and of being the one who had really committed the abuses. The opinion of the patient could not be sought, as the elderly resident concerned was suffering from advanced dementia. Fortunately, the matter was eventually resolved to everyone’s satisfaction. The administrator took the allegation seriously and, later, took the initiative to emphasise to all staff the importance of protecting and upholding residents’ rights. The student was reassured that she had done the ‘right thing’, and that she had fulfilled her professional and moral obligations both (1) in reporting the incident, and (2) in the manner in which she had reported it (i.e. she had followed proper processes). The clinical supervisor and administrator reached an agreement that any matters of concern discussed during clinical teaching placements be referred directly and immediately to the administrator for action. The staff member who was the subject of the unsubstantiated allegation was counselled in confidence by the administrator.

A fourth type of dilemma is taken from a feminist moral perspective, and is described by Gilligan (1982) in terms of being caught between attachments to people and trying to decide upon ways that will avoid ‘hurting’ each of these ‘attached people’. Gilligan uses the example of a woman contemplating an abortion; she argues that generally a woman faced with having to make a choice in this situation ‘contemplates a decision that affects both self and others and engages directly the critical moral issue of hurting’ (p 71). Here the question to be raised in contemplating a difficult choice is: How can I avoid hurting the people to whom I am attached?

It might be objected here that Gilligan’s sense of ‘hurt’ and ‘avoiding hurt’ is not very different from the general moral principle of non-maleficence and its demand to avoid or prevent ‘harm’. While I concede that ‘hurt’ is a type of harm, there is a subtle distinction between ‘hurt’ in the sense that I think Gilligan is using it and ‘harm’ in an abstract sense as used by philosophers. It is important to draw a distinction between these two notions so as not to obscure other important distinctions which can be drawn in our moral discourse. Let us examine this point a little more fully.

The sense in which ‘hurt’ is being used here is not simply ‘physical’, but rather existential, spiritual, and even ‘soulful’ or ‘soul-felt’. There is even room to make the radical claim that the notion of ‘avoiding hurt’ is not being asserted as a principle as such, but more as an attitude, and one which reminds us that we need to take very special care in our selection, interpretation and application of general moral principles in our everyday personal and professional lives. In short, it is an attitude which serves to mediate the use of more general moral principles. Consider, for example, the demand to ‘avoid hurt’ in a situation involving a patient who has yet to be told an unfavourable medical diagnosis. The demand to ‘avoid hurt’ reminds us that it is not enough just to give the patient the diagnosis (as may otherwise be required by the moral principle of autonomy), but that it must also be given in a caring, compassionate and culturally appropriate manner. Furthermore, it is not clear to me that the principle of non-maleficence fully captures the demand to be caring, compassionate and culturally appropriate in manner when performing such an unpleasant task as giving someone an unfavourable medical diagnosis. And in some instances, taken to its extreme, the principle of non-maleficence might even instruct that the diagnosis should not be given at all. ‘Avoiding hurt’, on the other hand, recognises that the information that needs to be given could be ‘harmful’ and is probably ‘hurtful’, but that there is a way of lessening if not avoiding this harm and hurt. To illustrate this point, consider the following case (told to me by a nursing colleague).

A young doctor walked into a patient’s room, stood at the end of the bed, and in full view and hearing distance of other patients in the room, and without greeting the patient or smiling, stated abruptly: ‘We’ve looked at your throat and the lump you have there is cancer.’ Without another word, the doctor then briskly walked off. The patient had previously expressed a desire to know the diagnosis when it was available, so in many respects we could conclude that the doctor acted ‘ethically’ in that the patient’s wishes had been respected and the requested information had been relayed to the patient. What is evident in this case is that the doctor had not considered ways to give the information less ‘hurtfully’ — or, if such ways had been considered, they were not heeded. For example, the doctor might have at least greeted the patient, used a compassionate tone of voice, drawn the curtains around the patient before speaking, sat down on a chair to be at the same level as the patient, and stayed long enough to allow the patient to ask questions, which the patient stated later she wanted to do. If the doctor felt inadequate to deal with this situation, it might have been advisable to wait until a medical colleague or a nurse was available to accompany him. Or, more simply, the doctor should have passed the task over to someone else who was more experienced and better prepared to deal with the situation. By using such an abrupt manner, the doctor not only failed to ‘avoid hurt’, but exacerbated it. To make matters worse, the diagnosis given to the patient later turned out to be incorrect. At the time of learning that in fact there was no cancer, the patient was still in a state of psychological shock. This could have been avoided had the situation been handled more compassionately and caringly, and with an attitude intent on ‘lessening hurt’. Within the same week, two other patients confided in my colleague that they had undergone similar experiences with the same doctor.

Of course, doctors are not the only ones who have exhibited hurtful attitudes towards others. I have seen many instances where nurses have likewise failed to avoid or to lessen the hurt of a given situation. I recall the tragic case of a middle-aged man who was dying from advanced cancer. A close friend and members of his family were greatly distressed about his deteriorating condition, and even accused the nursing staff of ‘trying to kill’ their loved one by giving him morphine for his pain. On one occasion the nursing staff observed the family friend clutching his friend and pleading with him not to accept the morphine injections, telling him: ‘Don’t you see, they are killing you! They are killing you! You don’t have to have them …’ The nursing staff tried to get the friend to leave, but he refused to go. When he became abusive, the nursing staff contacted a hospital security officer, and he was forcibly removed. There is, I believe, room to speculate about this case: had the friend’s grief been properly addressed by the nursing staff, and the dynamics and benefits of effective pain management fully explained to him, both he, and the patient, the patient’s family and attending nursing staff would have been spared the ‘hurt’ that this tragic situation caused.

These two cases demonstrate that ‘avoiding hurt’ is not something that can be fully directed or achieved by an abstract moral principle. Rather, it requires that we draw heavily on our past experience, knowledge, intuition, feelings and interpersonal skills, as well as on a thorough and systematic analysis of the facts of the situation at hand.

M oral stress, moral distress and moral perplexity2

It has long been recognised that nurses experience moral stress, moral distress and moral outrage during the course of their work (see, for example, Kopala & Burkhart 2005; Severinsson 2003; Sundin-Huard & Fahy 1999; Tiedje 2000; Corley & Raines 1993; Andersen 1990; Cahn 1989; Wilkinson 1987/88; Andrews & Fargotstein 1986; Jameton 1984). Defined as ‘the psychological disequilibrium and negative feeling state experienced when a person makes a moral decision but does not follow through by performing the moral behaviour indicated by that decision’ (Wilkinson 1987/88: 16), moral stress/distress can arise in a number of situations. Jameton (1984: 6) points out, for example, that nurses experience moral distress when they know the right thing to do, ‘but institutional constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action’. In such instances, unchecked moral stress and distress can turn into moral outrage which can, in turn, compound the original distress. Andersen explains (1990: 9):

Moral outrage is a product of the emotional turbulence, pain, incredulity, indignation, and rage that … occurs when a logical attempt to solve a moral problem results in denial of the problem and an assault on the nurse’s integrity by those who have sacrificed their integrity and the welfare of patients to preserve the status quo of submarginal performance. The psychobiological remnants of moral distress are then compounded by the experience of moral outrage.

Moral distress can also follow from moral perplexity, taken here to be a state of moral confusion or bewilderment that arises when a person is faced with a morally problematic situation, recognises it (the situation) as being morally problematic, has the resources for dealing with it, but genuinely does not know what is the right thing to do. Nurses can and do suffer moral perplexity when confronted with a range of moral problems (examples of which are given in this book). Perhaps among the most perplexing of moral problems faced by nurses are those otherwise known as moral dilemmas and moral disagreements (discussed above). These problems can be particularly perplexing in instances where it becomes apparent that, due to a variety of reasons, they may not be or indeed are not amenable to resolution.

M aking moral decisions

When encountering a moral problem, there comes a point at which we have to decide what to do about it and how best to go about doing what we have decided; that is, how best to address the problem (or problems) we have encountered. Invariably, when encountering a moral problem, the question arises of: ‘How do I decide what to do?’ and ‘How, if at all, should I act on what I have decided?’ Before considering these questions, it would be useful to first clarify what a moral decision is and the various processes that might be used for making moral decisions. Following this, attention will then be given to examining briefly how to deal with moral disagreements and disputes in workplace contexts.

M oral decision-making — a working definition

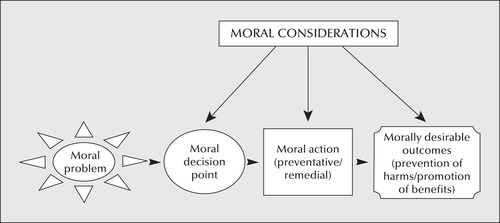

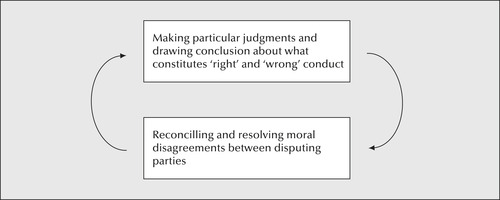

The word ‘decision’ (from the Latin dēcisiō, literally a ‘cutting off’) may be defined as ‘a judgment, conclusion or resolution reached or given’; it may also be defined as ‘the act of making up one’s mind’ ( Collins Australian Dictionary 2005). A moral decision may be similarly defined, that is, as a moral judgment, moral conclusion or moral resolution reached or given, notably, about what constitutes ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ conduct. Moral decision-making may be further defined as that which is fundamentally concerned with reconciling moral disagreements between disputing parties, each of whom may hold equally valid moral viewpoints and may reach different yet reasonable conclusions on what constitutes ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ conduct in a given context (Wong 1992). These two different yet related aspects of moral decision-making are depicted in Figure 5.3.

|

| Figure 5.3 |

An essential and distinguishing feature of moral decisions is that they are based on and informed by moral considerations, which are regarded as paramount to the moral decision-making process. Another distinguishing feature of moral decisions is that they provide a definitive starting point from which moral action can be taken in order to prevent moral harms from occurring and to promote morally desirable or at least tolerable outcomes (see Figure 5.4).

P rocesses for making moral decisions

Moral decisions can be made either by an individual (e.g. a nurse, doctor, and so on) or by a collective entity (e.g. a health care team, a stakeholder group or a committee). In either case, the decision-making process needs to be approached with the utmost diligence, vigilance and wisdom. Decision-makers need to take particular care in ensuring that a careful appraisal is made of the relevant facts of the matter as well as of the values that are operating in the given context at hand. One reason for this is that facts/values can each exert considerable influence on the other and, as a consequence, may even lead to profound changes in our conceptions of them and hence the moral decision we ultimately make. This is because, as Benjamin (2001: 25) explains:

What counts as relevant factual considerations may change as explorations of an ethical issue progresses. In some cases, facts considered important at the outset fade into the background as others, barely noticed at first, come to the fore. In others […] we not merely replace one set of factual considerations with another, but the facts either alter our ethical values and principles or we revise factual consideration in the light of values and principles.

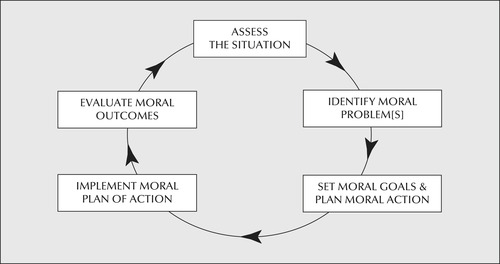

One way of ensuring that moral decision-making is approached in a wise, diligent and vigilant way is to use a systematic step-by-step decision-making process, much like the five-step decision-making process that has become universally associated with the nursing process. Such a five-step process requires moral decision-makers to:

1. assess the situation (including making a diligent appraisal of the relevant facts of the matter and operating values in the situation at issue)

2. diagnose or identify the moral problem(s) at hand

3. set moral goals and plan an appropriate moral course of action to address the moral problems identified

4. implement the plan of moral action

5. evaluate the moral outcomes of the action implemented.

(Note: In the event that a morally desirable outcome has not been achieved, this process will need to be repeated.)

This model may be expressed diagrammatically as shown in Figure 5.5.

|

| Figure 5.5 |

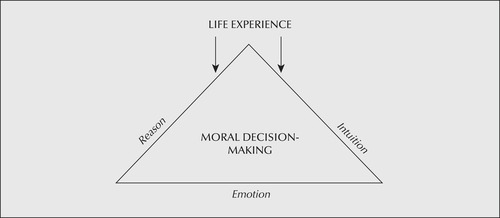

It needs to be clarified at this point that when using a systematic moral decision-making process, deliberations during each of the steps identified involve appeals to reason, emotion and intuition, with each of these, in turn, being informed or ‘fine-tuned’ by life experience (see Figure 5.6, p 124).

|

| Figure 5.6 |

Moral decision-making also requires moral imagination — that is, an ability to reflect and imagine possible moral ‘futures’ (options) and solutions to problems, and possible ways of progressing these even in situations that are hostile to moral considerations and which may also involve a ‘moral deadlock’. Since the role of reason, emotion, intuition and life experience in moral decision-making is not always understood and, ironically, has itself been the subject of moral dispute, some further discussion of it is warranted here. Consider the following.

Reason and moral decision-making

Throughout history dating back to the days of the Ancient Greek philosophers, it has been popularly assumed (and argued) by moral philosophers that, in order for a moral decision to be ‘sound’, it must be based on rational or ‘reasoned’ (abstract) moral principles of conduct. The thinking behind this view (which dates back to the works of the Ancient Greek philosophers) is that, unlike feelings (e.g. emotion and intuition which are, by their nature, value-laden and subjective), reason is value-neutral and objective, and therefore more reliable and hence supreme as an enlightened authority on how best to conduct one’s behaviour in the world of competing self-interest. By this view, to be rational is to be moral since, by upholding rationality as the supreme principle of morality, decision-makers will be able to avoid the ‘corrupting influences of the passions’ and thereby avoid falling prey to deciding in favour of their own self-interests.

An influential advocate of this view was the German philosopher, Immanuel Kant (1724–1804).