History

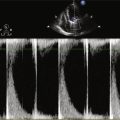

FIGURE 48-1 Decreased quantities of biventricular pacing present along with activity level trends. AF, Atrial fibrillation; AT, atrial tachycardia; V, ventricular.

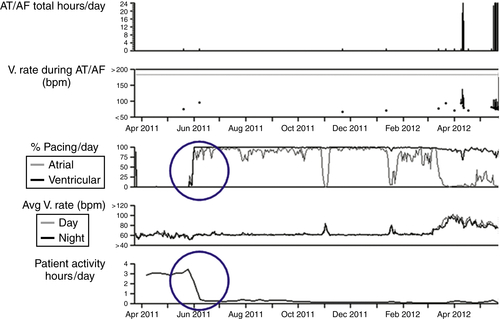

TABLE 48-1

Remote Arrhythmia Episode List

| Type | ATP Seq | Shocks | Success | ID no. | Date | Time hh:mm | Duration hh:mm:ss |

Average BPM A/V |

| AT/AF | 102 | 17-Sep-2012 | 04:32 | (Episode in progress) | ||||

| AT/AF | 101 | 17-Sep-2012 | 03:48 | :44:22 | 178/98 | |||

| AT/AF | 100 | 17-Sep-2012 | 00:16 | 03:31:53 | 180/90 | |||

| AT/AF | 99 | 16-Sep-2012 | 02:17 | 21:58:27 | 180/91 | |||

| AT/AF | 98 | 15-Sep-2012 | 23:20 | 02:57:42 | 178/89 | |||

| AT/AF | 97 | 15-Sep-2012 | 01:10 | 22:09:17 | 180/90 | |||

| AT/AF | 96 | 15-Sep-2012 | 00:06 | 01:04:13 | 175/87 | |||

| AT/AF | 95 | 14-Sep-2012 | 14:10 | 09:56:19 | 178/88 | |||

| AT/AF | 94 | 14-Sep-2012 | 13:59 | :10:43 | 176/88 | |||

| AT/AF | 93 | 14-Sep-2012 | 08:20 | 05:38:34 | 176/88 | |||

| AT/AF | 92 | 14-Sep-2012 | 05:22 | 02:57:52 | 176/86 | |||

| AT/AF | 91 | 13-Sep-2012 | 19:38 | 09:44:24 | 169/83 | |||

AF, Atrial fibrillation; AT, atrial tachycardia; ATP Seq, anti-tachycardial pacing sequence; A/V, atrioventricular; BPM, beats per minute; hh, hours; ID, identification; mm, minutes; ss; seconds.

Current Medications

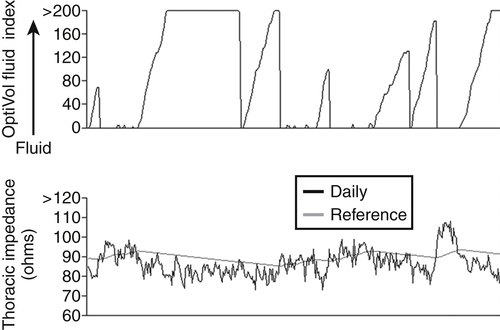

FIGURE 48-2 Intrathoracic impedance trends.

Comments

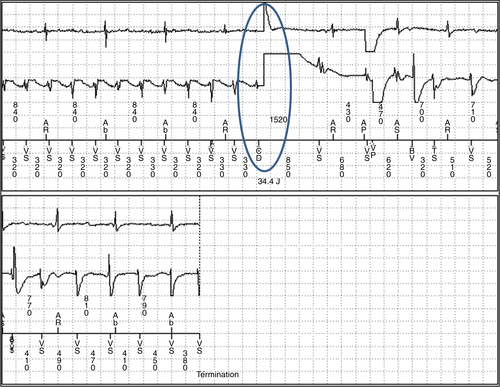

FIGURE 48-3 Ventricular tachycardia with a 35-J shock.

Physical Examination

Laboratory Data

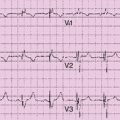

Electrocardiogram

Chest Radiograph

Exercise Testing

Dyssynchrony Echocardiogram

Cardiac Catheterization

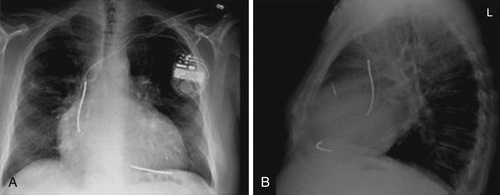

FIGURE 48-4 Chest radiographs. A, Posterior anterior view. B, Lateral view.

Pulmonary Function Testing

Outcome

Final Diagnosis

Comments

Figure 48-5 Atrial flutter with ventricular sensed response pacing and loss of true biventricular pacing. EGM, Electrogram; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; SVC, superior vena cava; VS, ventricular sensing.

Focused Clinical Questions and Discussion Points

Question

Discussion

Question

Discussion

Question

Discussion

Question

Discussion

Selected References

1. Daubert J.C., Saxon L., Adamson P.B. et al. 2012 EHRA/HRS expert consensus statement on cardiac resynchronization therapy in heart failure: implant and follow-up recommendations and management. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:1524–1576.

2. Folino A.F., Chiusso F., Zanotto G. et al. Management of alert messages in the remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter defibrillators and pacemakers: an Italian single-region study. Europace. 2011;13:1281–1291.

3. Hayes D.L., Boehmer J.P., Day J.D. et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy and the relationship of percent biventricular pacing to symptoms and survival. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1469–1475.

4. Koplan B.A., Kaplan A.J., Weiner S. et al. Heart failure decompensation and all-cause mortality in relation to percent biventricular pacing in patients with heart failure: is a goal of 100% biventricular pacing necessary? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:355–360.

5. Lazarus A. Remote, wireless, ambulatory monitoring of implantable pacemakers, cardioverter defibrillators, and cardiac resynchronization therapy systems: analysis of a worldwide database. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2007;30(Suppl 1):S2–S12.

6. Marinskis G., van Erven L., Bongiorni M.G. et al. Practices of cardiac implantable electronic device follow-up: results of the European Heart Rhythm Association survey. Europace. 2012;14:423–425.

7. Saxon L.A., Hayes D.L., Gilliam F.R. et al. Long-term outcome after ICD and CRT implantation and influence of remote device follow-up: the ALTITUDE survival study. Circulation. 2010;122:2359–2367.

8. Singh J.P., Rosenthal L.S., Hranitzky P.M. et al. Device diagnostics and long-term clinical outcome in patients receiving cardiac resynchronization therapy. Europace. 2009;11:1647–1653.

9. van Veldhuisen D.J., Braunschweig F., Conraads V. et al. Intrathoracic impedance monitoring, audible patient alerts, and outcome in patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2011;124:1719–1726.

10. Whellan D.J., Ousdigian K.T., Al-Khatib S.M. et al. Combined heart failure device diagnostics identify patients at higher risk of subsequent heart failure hospitalizations: results from PARTNERS HF (Program to Access and Review Trending Information and Evaluate Correlation to Symptoms in Patients With Heart Failure) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1803–1810.