Endotracheal Tube and Oral Care

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Anatomy and physiology of the pulmonary system should be understood.

• Anatomy and physiology of the oral cavity and the importance of evidence-based oral hygiene procedures on a regular basis should be understood.1,18,21,27,49,54

• Endotracheal (ET) tubes are used to maintain a patent airway or to facilitate mechanical ventilation. The presence of these artificial airways, especially ET tubes, prevents effective coughing and secretion removal, necessitating periodic removal of pulmonary secretions with suctioning.

• Oral care given every 2 to 4 hours appears to provide a greater improvement in oral health. If oral care is not provided for 4 to 6 hours, previous benefits are thought to be lost.10

• Suctioning of airways should be performed only for clinical indications and not as a routine fixed-schedule treatment (see Procedure 12). In acute care situations, suctioning is performed as a sterile procedure to prevent healthcare-acquired pneumonia.

• Adequate systemic hydration and supplemental humidification of inspired gases assist in thinning secretions for easier aspiration from airways.20,36,37,51

• Appropriate cuff care (see Procedure 13) helps prevent major pulmonary aspirations, prepares for tracheal extubation, decreases the risk of inadvertent extubation, provides a patent airway for ventilation and removal of secretions, and decreases the risk of iatrogenic infections.5,15,29,37,51

• Constant pressure from the ET tube on the mouth or nose can cause skin breakdown.

• If the patient is anxious or uncooperative, use of two caregivers for retaping or repositioning the endotracheal tube helps prevent accidental dislodgment of the tube.

• The incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is increased in patients intubated for longer than 24 hours.36,37,51

• Nasotracheal intubation should be avoided because it increases the risk of VAP.37,51

• VAP is a risk factor for endotracheal intubation.

VAP is thought to be related to aspiration of gastric or oral secretions and colonization of the mouth related to dental plaque.14,18,19,37,38,51

VAP is thought to be related to aspiration of gastric or oral secretions and colonization of the mouth related to dental plaque.14,18,19,37,38,51

VAP increases not only ventilator and intensive care unit (ICU) days and hospital length of stay, but also overall morbidity and mortality of the critically ill patient.33,37,39,41,44,47,51,55

VAP increases not only ventilator and intensive care unit (ICU) days and hospital length of stay, but also overall morbidity and mortality of the critically ill patient.33,37,39,41,44,47,51,55

EQUIPMENT

• Bite-block or oral airway if needed

• Adhesive or twill tape; commercial endotracheal tube holder (design must ensure ability to provide oral care and suctioning)

• 2 × 2 Gauze or cotton swab for cleaning around the nares

• Soft pediatric/adult toothbrush or suction toothbrush

• Toothettes/oral swab/oral suction swab

• Oral cleansing solution (e.g., 1.5% H2O2,3,18,31,44,47 chlorhexidine,3,6,9,16,22,23,26,34,52 cetylpyridinium chloride [CPC],3,30,43,50 toothpaste10,24,40)

Additional equipment, to have available as needed, includes the following:

• Closed-suction setup with a catheter of appropriate size (Table 4-1)

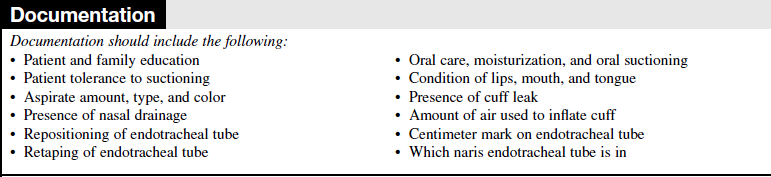

TABLE 4-1

Guidelines for Catheter Size for Endotracheal and Tracheostomy Tube Suctioning*

*This guide should be used as an estimate only. Actual sizes depend on the size and individual needs of the patient.

(From St John RE, Seckel MA: Airway management. In AACN protocols for practice: care of the mechanically ventilated patient series, ed 2, Aliso Viejo, CA, 2002, American Association of Critical-Care Nurses.)

• Sterile saline solution lavage containers for cleansing the closed suction system after use (5 to 10 mL)

• Suction catheter for oral and nasal suctioning (single-use Yankauer, covered Yankauer, disposable oral saliva ejector)

• Two sources of suction or a bifurcated connection device attached to a single suction source

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the procedure to the patient and family, including the purpose of ET tube care and the importance of comprehensive oral care in prevention of infection.1  Rationale: This step identifies patient and family knowledge deficits concerning patient condition, procedure, expected benefits, and potential risks and allows time for questions to clarify information and voice concerns. Explanations decrease patient anxiety and enhance cooperation.

Rationale: This step identifies patient and family knowledge deficits concerning patient condition, procedure, expected benefits, and potential risks and allows time for questions to clarify information and voice concerns. Explanations decrease patient anxiety and enhance cooperation.

• If indicated, explain the patient’s role in assisting with ET tube care.  Rationale: Eliciting the patient’s cooperation assists with care.

Rationale: Eliciting the patient’s cooperation assists with care.

• Explain that the patient will be unable to speak while the ET tube is in place but that other means of communication will be provided.  Rationale: This information enhances patient and family understanding and decreases anxiety.

Rationale: This information enhances patient and family understanding and decreases anxiety.

• Explain that the patient’s hands may be immobilized to prevent accidental dislodgment of the tube.  Rationale: This information enhances patient and family understanding and decreases anxiety.

Rationale: This information enhances patient and family understanding and decreases anxiety.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Assess for signs and symptoms that indicate that oral cavity and ET tube care is necessary.

Excessive secretions (oral or tracheal)

Excessive secretions (oral or tracheal)

Soiled tape or ties or commercial device

Soiled tape or ties or commercial device

Patient biting or kinking tube

Patient biting or kinking tube

Pressure areas on nares, corner of mouth, or tongue

Pressure areas on nares, corner of mouth, or tongue

ET tube moving in and out of mouth

ET tube moving in and out of mouth

Patient able to verbalize or audible air leak around ET tube

Patient able to verbalize or audible air leak around ET tube

•  Rationale: Assessment provides for early recognition that oral or ET tube care is needed.

Rationale: Assessment provides for early recognition that oral or ET tube care is needed.

• Assess level of consciousness and level of anxiety.  Rationale: This assessment determines the need for sedation during ET tube care and the number of care providers needed to perform the activities.

Rationale: This assessment determines the need for sedation during ET tube care and the number of care providers needed to perform the activities.

Patient Preparation

• Ensure that the patient understands preprocedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: This process evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

Rationale: This process evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

• Maintain the patient in a semi-Fowler’s (≥30 degrees) position during mechanical ventilation to reduce the risk of aspiration.13,36,37,51,53 Assist the patient to a high Fowler’s position or the most comfortable position for both the patient and nurse before performing the care.  Rationale: This position promotes comfort and reduces physical strain and maintains head of bed elevation to reduce risk of aspiration.13,20,36,37,51,53

Rationale: This position promotes comfort and reduces physical strain and maintains head of bed elevation to reduce risk of aspiration.13,20,36,37,51,53

References

1. Berry, AM, Davidson, PM, et al. Systematic literature review of oral hygiene practices for intensive care patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Am J Crit Care. 2007; 16(6):552–563.

2. Carlson, J, Mayrose, J, et al, Extubation force. tape versus endotracheal tube holders. Ann Emerg Med. 2007; 50(6):686–691.

3. Chan, EY, et al, Oral decontamination for prevention of pneumonia in mechanically ventilated adults. systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2007; 334:889–893.

4. Chao, YF, et al, Removal of oral secretion prior to position change can reduce the incidence of ventilator- associated pneumonia for adult ICU patients. a clinical controlled trial study. J Clin Nurs. 2009; 18(1):22–28.

![]() 5. Chendrasekhar, A, Timberlake, GA. Endotracheal tube cuff pressure threshold for prevention of nosocomial pneumonia. J Applied Res. 2003; 3(3):311–314.

5. Chendrasekhar, A, Timberlake, GA. Endotracheal tube cuff pressure threshold for prevention of nosocomial pneumonia. J Applied Res. 2003; 3(3):311–314.

6. Chlebicki, MP, Safdar, N, Topical chlorhexidine for prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2007; 35(2):595–602.

![]() 7. Cummins RO, ed.. Adjuncts for airway control, oxygenation, and ventilation. ACLS : principles and practice. American Heart Association: Dallas, 2003:167.

7. Cummins RO, ed.. Adjuncts for airway control, oxygenation, and ventilation. ACLS : principles and practice. American Heart Association: Dallas, 2003:167.

8. De Pew CL, et al, Subglottic secretion drainage. a literature review. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2007; 18(4):366–379.

![]() 9. DeRiso, AJ, II., et al. Chlorhexidine gluconate 0. 12% oral rinse reduces the incidence of total nosocomial respiratory infection and nonprophylactic systemic antibiotic use in patients undergoing heart surgery. Chest. 1996; 109:1556–15161.

9. DeRiso, AJ, II., et al. Chlorhexidine gluconate 0. 12% oral rinse reduces the incidence of total nosocomial respiratory infection and nonprophylactic systemic antibiotic use in patients undergoing heart surgery. Chest. 1996; 109:1556–15161.

![]() 10. DeWalt, EM. Effect of timed hygienic measures on oral mucosa in a group of elderly subjects. Nurs Res. 1975; 24:104–108.

10. DeWalt, EM. Effect of timed hygienic measures on oral mucosa in a group of elderly subjects. Nurs Res. 1975; 24:104–108.

11. Dezfulian, C, et al, Subglottic secretion drainage for preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia. a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2005; 118(1):11–18.

12. Dragoumanis, CK, et al. Investigating the failure to aspirate subglottic secretions with Evac endotracheal tube. Anesth Analg. 2007; 105:1083–1085.

![]() 13. Drakulovic, MB, et al, Supine body position as a risk factor for nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients. a randomized trial. Lancet 1999; 354:1851–1858.

13. Drakulovic, MB, et al, Supine body position as a risk factor for nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients. a randomized trial. Lancet 1999; 354:1851–1858.

![]() 14. El-Solh AA, et al, Colonization of dental plaque. a reservoir of respiratory pathogens for hospital acquired pneumonia in institutionalized elders. Chest 2004; 126:1575–1582.

14. El-Solh AA, et al, Colonization of dental plaque. a reservoir of respiratory pathogens for hospital acquired pneumonia in institutionalized elders. Chest 2004; 126:1575–1582.

15. Ferrer M, et al, Maintenance of tracheal tube cuff pressure. where are the limits [commentary]. Crit Care 2008; 12:106–107.

![]() 16. Ferretti, GA, et al. Chlorhexidine for prophylaxis against oral infections and associated complications in patients receiving bone marrow transplants. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987; 114:461–467.

16. Ferretti, GA, et al. Chlorhexidine for prophylaxis against oral infections and associated complications in patients receiving bone marrow transplants. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987; 114:461–467.

17. Frost, P, Wise, MP, Tracheotomy and ventilator-associated pneumonia. the importance of oral care. Eur Respir J. 2008; 31(1):221–222.

18. Garcia, R, A review of the possible role of oral and dental colonization on the occurrence of healthcare-associated pneumonia. underappreciated risk in a call for interventions. Am J Infect Control. 2005; 33(9):527–541.

![]() 19. Garrouste-Orgeas M, et al, Oropharyngeal or gastric colonization and nosocomial pneumonia in adult intensive care unit patients. a prospective study based on genomic DNA analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 156:1647–1655.

19. Garrouste-Orgeas M, et al, Oropharyngeal or gastric colonization and nosocomial pneumonia in adult intensive care unit patients. a prospective study based on genomic DNA analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 156:1647–1655.

![]() 20. Gastmeier, P, Geffers, C, Prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. analysis of studies published since 2004. J Hosp Infect. 2007; 67(1):1–8.

20. Gastmeier, P, Geffers, C, Prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. analysis of studies published since 2004. J Hosp Infect. 2007; 67(1):1–8.

![]() 21. Grap, MJ, et al, Oral care interventions in critical care. frequency and documentation. Am J Crit Care 2003; 12:113–119.

21. Grap, MJ, et al, Oral care interventions in critical care. frequency and documentation. Am J Crit Care 2003; 12:113–119.

22. Grap, MJ, et al, Duration of action of a single, early oral application of chlorhexidine on oral microbial flora in mechanically ventilated patients. a pilot study. Heart Lung 2004; 33:83–91.

![]() 23. Houston, S, et al. Effectiveness of 0. 12% chlorhexidine gluconate oral rinse in reducing prevalence of nosocomial pneumonia in patients undergoing heart surgery. Am J Crit Care. 2002; 11:567–570.

23. Houston, S, et al. Effectiveness of 0. 12% chlorhexidine gluconate oral rinse in reducing prevalence of nosocomial pneumonia in patients undergoing heart surgery. Am J Crit Care. 2002; 11:567–570.

24. Ishikawa, A, Yoneyama, T, et al. Professional oral health care reduces the number of oropharyngeal bacteria. J Dent Res. 2008; 87(6):594–598.

![]() 25. Kaplow, R, Bookbinder, M. A comparison of four endotracheal tube holders. Heart Lung. 1994; 23(1):59–66.

25. Kaplow, R, Bookbinder, M. A comparison of four endotracheal tube holders. Heart Lung. 1994; 23(1):59–66.

26. Koeman, M, et al. Oral decontamination with chlorhexidine reduces the incidence of ventilator associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006; 173:1348–1355.

27. Labeau, S, Vandijck, D, et al, Evidence-based guidelines for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia . results of a knowledge test among European intensive care nurses. J Hosp Infect. 2008; 70(2):180–185.

28. Lansford, T, Moncure, M, et al. Efficacy of a pneumonia prevention protocol in the reduction of ventilator-associated pneumonia in trauma patients. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2007; 8(5):10–505.

29. Lorente, L, et al. Evidence on measures for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2007; 30:1193–1207.

30. Mankodi, S, et al. A 6- month clinical trial to study the -effects of a cetylpyridinium chloride mouth rinse on gingivitis and plaque. Am J Dent. 2005; 18:9A–14A.

![]() 31. Marshall, MV, Cancro, LP, Fischman, SL, Hydrogen peroxide. a review of its use in dentistry. J Periodontol 1995; 66:786–796.

31. Marshall, MV, Cancro, LP, Fischman, SL, Hydrogen peroxide. a review of its use in dentistry. J Periodontol 1995; 66:786–796.

32. Mori, H, et al. Oral care reduces incidence of ventilator -associated pneumonia in ICU populations. Intensive Care Med. 2006; 32:230–236.

![]() 33. Munro, CL, Grap, MJ, Oral health and care in the intensive care unit. state of the science. Am J Crit Care 2004; 13:25–33.

33. Munro, CL, Grap, MJ, Oral health and care in the intensive care unit. state of the science. Am J Crit Care 2004; 13:25–33.

34. Munro, CL, et al, Chlorhexidine reduces ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP) in mechanically ventilated ICU adults. Crit Care Med 24 2006; 12:A1 [(suppl)].

35. Murdoch, E, Holdgate, A. A comparison of tape-tying versus a tube-holding device for securing endotracheal tubes in adults. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2007; 35(5):730–735.

36. Muscedere, J, et al, Comprehensive evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for ventilator associated pneumonia. prevention. J Crit Care 2008; 23:126–137.

37. Niederman, MS, Craven, DE, et al. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital- acquired, ventilator- -associated and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005; 171:388–416.

38. Paju, S, Scannapieco, FA. Oral biofilms, periodontitis, and pulmonary infections. Oral Dis. 2007; 13(6):508–512.

39. Papadimos, TJ, Hensley, SJ, et al. Implementation of the “FASTHUG” concept decreases the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia in a surgical intensive care unit. Patient Saf Surg. 2008; 2:3.

![]() 40. Pearson, LS, Hutton, JL. A controlled trial to compare the ability of foam swabs and toothbrushes to remove dental plaque. J Adv Nurs. 2002; 39:480–489.

40. Pearson, LS, Hutton, JL. A controlled trial to compare the ability of foam swabs and toothbrushes to remove dental plaque. J Adv Nurs. 2002; 39:480–489.

41. Safdar, N, Dezfulian, C, et al, Clinical and economic consequences of ventilator-associated pneumonia. a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2005; 33(10):2184–2193.

42. Scannapieco, FA, Pneumonia in nonambulatory patients. the role of oral bacteria and oral hygiene. J Am Dent -Assoc 2006; 137:21S–25S [(Suppl)].

43. Schiffner, U, Plaque and gingivitis in the elderly. a randomized, single blinded clinical trial on the outcome of intensified mechanical or anti-bacterial oral hygiene measures. J Clin Periodontol 2007; 34:1068–1073.

![]() 44. Schleder, B, Stott, K, Lloyd, RC. The effect of a comprehensive oral care protocol on patients at risk for ventilator-associated pneumonia. J Advocate Health Care. 2002; 4:27–30.

44. Schleder, B, Stott, K, Lloyd, RC. The effect of a comprehensive oral care protocol on patients at risk for ventilator-associated pneumonia. J Advocate Health Care. 2002; 4:27–30.

![]() 45. Shibly, O, et al. Clinical evaluation of a hydrogen peroxide mouth rinse, sodium chlorhexidine, for prophylaxis against oral infections and associated bicarbonate dentifrice, and mouth moisturizer on oral health. J Clin Dent. 1997; 8:145–149.

45. Shibly, O, et al. Clinical evaluation of a hydrogen peroxide mouth rinse, sodium chlorhexidine, for prophylaxis against oral infections and associated bicarbonate dentifrice, and mouth moisturizer on oral health. J Clin Dent. 1997; 8:145–149.

![]() 46. Shorri, A, O’Malley, P, Continuous subglottic suctioning for the prevention of VAP. potential economic impact. Chest 2001; 119:228–238.

46. Shorri, A, O’Malley, P, Continuous subglottic suctioning for the prevention of VAP. potential economic impact. Chest 2001; 119:228–238.

![]() 47. Simmons-Trau D, et al. Reducing VAP with 6 sigma. Nurs Manage. 2004; 35(6):41–45.

47. Simmons-Trau D, et al. Reducing VAP with 6 sigma. Nurs Manage. 2004; 35(6):41–45.

![]() 48. Sole, ML, Poalillo, FE, et al, Bacterial growth in secretions and on suctioning equipment of orally intubated patients. a pilot study. Am J Crit Care. 2002; 11(2):141–149.

48. Sole, ML, Poalillo, FE, et al, Bacterial growth in secretions and on suctioning equipment of orally intubated patients. a pilot study. Am J Crit Care. 2002; 11(2):141–149.

![]() 49. Sole, ML, et al. A multisite survey of suctioning techniques and airway management practices. Am J Crit Care. 2003; 12:220–232.

49. Sole, ML, et al. A multisite survey of suctioning techniques and airway management practices. Am J Crit Care. 2003; 12:220–232.

![]() 50. Stookey, GK, et al. A 6-month clinical study assessing the safety and efficacy of two cetylpyridinium chloride mouth rinses. Am J Dent. 2005; 18:24A–28.

50. Stookey, GK, et al. A 6-month clinical study assessing the safety and efficacy of two cetylpyridinium chloride mouth rinses. Am J Dent. 2005; 18:24A–28.

51. Tablan, OC, Anderson, LJ, et al, Guidelines for preventing health-care-associated pneumonia, 2003. recommendations of CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices -Advisory Committee. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2004; 53(RR-3):1–36.

52. Tantipong, H, Morkchareonpong, C, et al. Randomized controlled trial and meta-analysis of oral decontamination with 2% chlorhexidine solution for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008; 29(2):131–136.

![]() 53. Torres, A, et al, Pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents in patients receiving mechanical ventilation. the effect of body position. Ann Intern Med, 1992; 116:540–543.

53. Torres, A, et al, Pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents in patients receiving mechanical ventilation. the effect of body position. Ann Intern Med, 1992; 116:540–543.

54. Vollman, KM. Ventilator associated pneumonia and pressure ulcer prevention as targets for quality improvement in the ICU. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2006; 18:453–467.

55. Westwell, S. Implementing a ventilator care bundle in an adult intensive care unit. Nurs Crit Care. 2008; 13(4):203–207.