CHAPTER 38 Grief, Bereavement, and Adjustment Disorders

GRIEF AND BEREAVEMENT

Definition

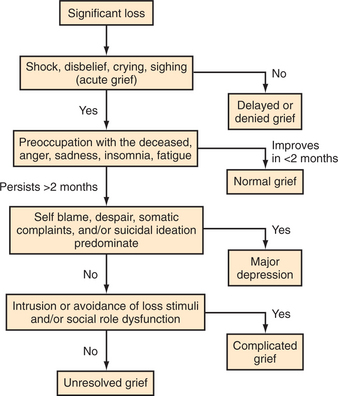

Grief may be defined as the physical and emotional pain precipitated by a significant loss (Figure 38-1). The loss may be of a person or pet, but it can also be of a meaningful place, job, or object. A term closely related to grief is bereavement, which literally means to be robbed by death. Many subtypes of grief have been suggested; some of the more commonly used subtypes can be found in Table 38-1.1,2

| Anticipatory grief | A grief reaction that occurs in anticipation of an impending loss; its symptoms include anger, guilt, anxiety, irritability, sadness, feelings of loss, and a decreased ability to perform usual tasks.1 |

| Acute grief | The first stage of the process of bereavement. Symptoms may begin immediately following the loss, or may be delayed. |

| Delayed grief | The absence of the expression of grief at the time of a loss. |

| Unresolved grief | Grief symptoms that reach extremes of intensity, duration, or tenacity.2 |

| Complicated grief | Unresolved grief plus clinical complications (e.g., physical symptoms) that interfere with daily function.2 |

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Psychoanalytic and attachment theories3–5 continue to dominate current thinking about the risk factors for pathological grief. A major theme is the belief in the influence of early relationships on a person’s ability to process loss. This theory has had important implications for the diagnosis and treatment of grief.

In the general population of the United States, estimates suggest that more than 1 million people each year develop complicated grief. Researchers have found that 40% to 55% of psychiatric outpatients have experienced one or more losses (through death); the average in one study was nearly three losses.2,6 A study of psychiatric outpatients found that one-third met or exceeded the criteria for complicated grief2; the symptoms of complicated grief were distinct from those of major depression and anxiety.7–9

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

While grief may be universal, each individual’s experience of bereavement is unique. When confronted by a grieving person, the physician is often challenged to determine whether the person’s grief is proceeding normally. This determination is often complicated by the fact that the severity and duration of grief vary widely; grief is shaped by sociocultural influences, and it does not necessarily proceed smoothly from one phase to another.10,11 The dearth of information about abnormal bereavement in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) reflects the lack of a general consensus regarding the differences between pathological and normal grief. Recent research on the subject is highlighted below.

Many investigators have described the stages of normal bereavement.4,12–14 One useful guideline proposes three overlapping phases: (1) shock, denial, and disbelief, followed by (2) a stage of mourning that involves physical as well as emotional symptoms and social isolation, eventually arriving at (3) a reorganization of a life that acknowledges, but is not defined by, the loss of the loved one.

Nonpathological grief can bring many symptoms reminiscent of depression: decreased appetite, difficulty with concentration, sleep disturbances, self-reproach, and even hallucinations of the deceased’s image or voice (though reality testing remains intact in normal grief). Assessment of various dimensions of the mourner’s experience can provide a more complete diagnostic picture13 (Table 38-2).

| Emotional and cognitive responses to the death of a loved one | May include anger, guilt, regret, anxiety, intrusive images, feelings of being overwhelmed, relieved, or lonely |

| Coping with emotional pain | Mourners may employ several strategies (e.g., involvement with others, distraction, avoidance, rationalization, the direct expression of feelings, disbelief, or denial, use of faith or religious guidance, or indulgence in “forbidden” activities) |

| A continuing relationship with the deceased | The mourner’s connection with the deceased may be maintained through symbolic representations, adoption of traits of the deceased, cultural rituals, or various means of continued contact (e.g., dreams or attempts at communication) |

| Changes in daily function | Survivors may experience changes in their mental or physical health or their social, family, or work functions |

| Changes in relationships | The death of a loved one can profoundly shift the dynamics of a survivor’s relationships with family, friends, and co-workers |

| Changes in self-identity | As the mourning process proceeds, the grieving person may experience himself or herself in new ways that may lead to the development of a new identity (e.g., an orphan, an only child, a widow, or a single parent) |

Adding to the difficulty in assessing grief is the lack of consensus regarding a normal duration of bereavement. At the very least, it may be safely said that the symptoms of grief usually last longer than anyone (mourner or observer) would like. Features of normal grief (e.g., anniversary reactions) may continue indefinitely, even in otherwise well-functioning individuals. The severity and duration of grief may also vary among cultural groups. The DSM-IV15 suggests that in the aftermath of loss, the diagnosis of major depressive episode should be reserved for those individuals whose grief symptoms are severe and persist beyond 2 months following the loss. Also, symptoms that extend beyond the context of the loss (e.g., guilt about worldly events that bear no direct connection to the mourner or the deceased) should alert the clinician to the possibility of an Axis I disorder.

The DSM-IV does not classify grief as a major psychiatric disorder, but bereavement is given a “V” code as a condition that may be the focus of clinical attention. Despite this lack of recognition by the DSM-IV, many observers have described what Lindemann termed “distortions of normal grief.”16 Delayed grief may simply be a manifestation of a person’s cultural expectations, or may signal a potentially pathological problem. If an individual is unable to deal with the reality of a significant loss, the grief may be distorted in its expression. The survivor may begin to experience physical symptoms similar to those experienced by the deceased, or may have unexplained anniversary reactions.

The syndromes of unresolved grief and complicated grief are distinguishable from, yet may co-exist with, major depression, and respond to specific treatment.17 In unresolved grief, the grief symptoms are especially recalcitrant and do not seem to follow a path toward resolution. Key features of complicated grief include a sense of disbelief regarding the death, anger and bitterness over the death, recurrent pangs of painful emotions, and a preoccupation with thoughts of the lost loved one (that often include distressing intrusive thoughts related to the death).17 Clinical complications may include anxiety, physical morbidity, social/occupational/familial dysfunction, or health-compromising behaviors (e.g., noncompliance with prescribed medical treatment).18,19

An algorithmic presentation of the differential diagnosis of grief and bereavement is provided in Figure 38-2.

Treatment

Studies have shown that psychiatric outpatients with complicated grief who entered interpretive group psychotherapy aimed at addressing unconscious conflicts that underlie grief symptoms demonstrated greater improvement than those who entered supportive group psychotherapy (that focused on problem-solving skills).7

Psychotherapeutic approaches to pathological grief in the previously undiagnosed patient range from psychodynamic to behavioral, and from individual to group settings. Again, the lack of widely accepted diagnostic criteria for pathological grief leaves the therapist to use his or her own background, training, and experience to tailor the treatment for each patient. Besides careful attention to the possibility of an emerging Axis I disorder, other key issues in working with a grieving person are summarized in Table 38-3.20

Table 38-3 Primary Psychotherapeutic Tasks When Working with a Bereaved Person

Prognosis

While most people do not become seriously ill or die in the initial grieving period, it is difficult to know what long-term health risks exist. However, certain risk factors for poor bereavement outcomes have been identified21 (Table 38-4).

| Demographic factors | Advanced age |

| Lower socioeconomic status | |

| Individual factors | Ambivalence or dependency in the relationship with the deceased |

| Health problems before bereavement | |

| Mode of death | Sudden death |

| Death of a child | |

| Stigmatized death (e.g., due to suicide) | |

| Circumstances following the loss | Lack of social support |

| Concurrent crises (e.g., financial problems) |

Current Controversies and Future Considerations Related to Grief and Bereavement

Research on grief and bereavement is beset by challenges in measurement and research design. Efforts to differentiate pathological grief from other syndromes (e.g., depression) are ongoing, but a diagnostic category for pathological grief has not yet been incorporated into the DSM. This limits both the applicability of such findings to clinical practice and future research into diagnosis and treatment.

ADJUSTMENT DISORDERS

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Estimates of the prevalence of adjustment disorders vary widely depending on the population studied and the methods of assessment used. In outpatient psychiatric settings, the percentage of patients diagnosed with an adjustment disorder ranges from 5% to 20%.22 Individuals in socioeconomically disadvantaged settings often face a high rate of stressors, as do those with chronic medical and psychiatric illness. These individuals may be at higher risk for the development of adjustment disorders than those in the general population. No race, age, or gender differences have been found to be risk factors for adjustment disorder.23

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of adjustment disorders is unknown, but investigators have observed neurochemical changes in patients with these disorders. Research has shown that platelet monoamine oxidase activity is lower and plasma cortisol levels are higher in patients with adjustment disorder and suicidality when compared to gender-matched controls.24

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

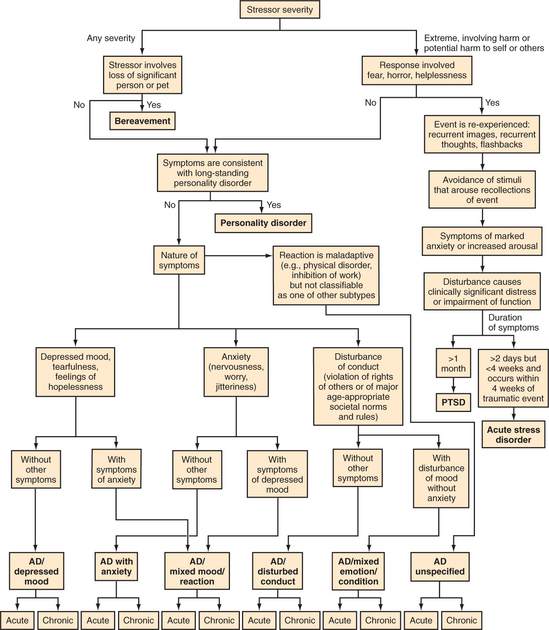

The diagnosis of an adjustment disorder is made when, within 3 months of the onset of a stressful event, a person develops behavioral or emotional symptoms that are in excess of what would be expected given the nature of the event. Adjustment disorders are subtyped according to whether the predominant symptoms are depressed mood, anxiety, or a disturbance of conduct. The symptoms are described as acute if they persist for less than 6 months, and as chronic if they last longer than 6 months. By definition, however, the symptoms cannot persist for more than 6 months after the termination of the stressor. Therefore, the designation of chronic adjustment disorder is given when the stressor itself (e.g., living in a dangerous neighborhood) is ongoing. Though the course of an adjustment disorder is usually brief, the symptoms can be severe and may include suicidal ideation. Each patient with an adjustment disorder should be evaluated thoroughly for his or her risk of self-injury. Figure 38-3 presents an algorithmic approach to the differential diagnosis of adjustment disorders.

Treatment

While no official consensus has been reached on the best treatment for adjustment disorders, psychotherapy is the treatment that is most frequently recommended. Individual therapy can help the patient identify his or her maladaptive responses to the stressor, maximize the use of his or her strengths, and provide support (Table 38-5). Group psychotherapy can be particularly helpful for individuals who share a common stressor (e.g., medical illness, divorce). Special care must be taken when treating the person with symptoms of a conduct disturbance, because the psychiatrist may be tempted to protect the patient from the consequences of the behavior. This approach carries the risk of depriving the patient of the opportunity to grow and to develop insight.25

Prognosis

When appropriately treated, most patients with an adjustment disorder will return to their previous level of function within 3 to 6 months. However, the risk of suicide in this population is significant and must be monitored. Studies of suicide have found that when compared to patients with major depression, individuals with an adjustment disorder have a shorter interval between the appearance of their first symptoms and the time of a suicide attempt.26,27 Limited longitudinal data suggest that adolescents diagnosed with an adjustment disorder are at higher risk of developing a major psychiatric illness.28

1 Theut SK, Jordan L, Ross LA, et al. Caregiver’s anticipatory grief in dementia: a pilot study. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1991;33:113-118.

2 Piper WE, Ogrodniczuk JS, Azim HF, et al. Prevalence of loss and complicated grief among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1069-1074.

3 Freud S, Mourning and melancholia Strachey J, editor. The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud, vol 20. London: Hogarth, 1917.

4 Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. In Loss: sadness and depression. New York: Basic Books; 1980.

5 Klein M. Mourning and its relation to manic-depressive states. In: Jones E, editor. Contributions to psychoanalysis. London: Hogarth, 1940.

6 Zisook S, Lyons L. Bereavement and unresolved grief in psychiatric outpatients. Omega. 1989-1990;20:307-322.

7 Ogrodniczuk JS, Piper WE, Joyce AS, et al. Differentiating symptoms of complicated grief and depression among psychiatric outpatients. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48:87-93.

8 Boelen PA, van den Bout J, de Keijser J. Traumatic grief as a disorder distinct from bereavement-related depression and anxiety: a replication study with bereaved mental health care patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1339-1341.

9 Prigerson HG, Jacobs SC. Traumatic grief as a distinct disorder: a rationale, consensus criteria, and a preliminary empirical test. In: Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Stroebe W, Schut HAW, editors. Handbook of bereavement research: consequences, coping, and care. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2001.

10 Kleinman A, Good B, editors Culture and depression: studies in the anthropology and cross-cultural psychiatry of affect and disorder 1985, University of California Press Berkeley 369-428

11 Eisenbruch M. Cross-cultural aspects of bereavement: ethnic and cultural variations in the development of bereavement practices. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1984;8(4):315-347.

12 Glick IO, Weiss RS, Parkes CM. The first year of bereavement. New York: Wiley, 1974.

13 Shuchter SR, Zisook S. The course of normal grief. In: Stroebe MS, Stroebe W, Hansson RO, editors. Handbook of bereavement theory, research, and intervention. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

14 Brown JT, Stoudemire GA. Normal and pathological grief. JAMA. 1983;250:378-382.

15 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, ed 4. Washington, DC: APA Press, 1994.

16 Lindemann E. Symptomatology and management of acute grief. Am J Psychiatry. 1944;101:141-148.

17 Shear K, Frank E, Houck PR, et al. Treatment of complicated grief: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:2601-2608.

18 Jacobs SC, Kim K. Psychiatric complications of bereavement. Psychiatr Ann. 1990;20:314-317.

19 Osterweis M, Solomon F, Green M. Bereavement: reactions, consequences, and care: a report of the Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1984.

20 Raphael B, Middleton W, Martinek N, et al. Counseling and therapy of the bereaved. In: Stroebe MS, Stroebe W, Hansson RO, editors. Handbook of bereavement theory, research, and intervention. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

21 Sanders CM. Risk factors in bereavement outcome. J Soc Issues. 1988;44:97-112.

22 Strain JJ. Adjustment disorders. In Gabbard GO, editor: Treatments of psychiatric disorders, ed 2, Washington, DC: APA Press, 1995.

23 Billings AG, Moos RH. The role of coping responses and social resources in attenuating the stress of life events. J Behav Med. 1981;4:139-157.

24 Tripodianakis J, Markianos M, Sarantidis D, et al. Neurochemical variables in subjects with adjustment disorder after suicide attempts. Eur Psychiatry. 2000;15(3):190-195.

25 Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, Grebb JA, editors Synopsis of psychiatryed 7;1994, Williams & Wilkins New York 727-731

26 Polyakova I, Knobler HY, Ambrumova A, et al. Characteristics of suicidal attempts in major depression versus adjustment reactions. J Affect Disord. 1998;47(1-3):159-167.

27 Schnyder U, Valach L. Suicide attempters in a psychiatric emergency room population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1997;19(2):119-129.

28 Andreasen N, Hoenk P. The predictive value of adjustment disorders: a follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:584.

Berkowitz DA. On the reclaiming of denied affects in family therapy. Fam Process. 1977;16(4):495-501.

Bowling A, Benjamin B. Mortality after bereavement: a followup study of a sample of elderly widowed people. Biol Soc. 1985;2:197-203.

Casarett D, Kutner JS, Abrahm J. Life after death: a practical approach to grief and bereavement. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:208-215.

Clayton P, Desmarais L, Winokur G. A study of normal bereavement. Am J Psychiatry. 1968;125(64):168-178.

Clayton PJ. Bereavement and depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51:34-40.

Depue RA, Monroe SM. Conceptualization and measurement of human disorder in life stress research: the problem of chronic disturbance. Psychol Bull. 1986;99:36-51.

Engel GL. Is grief a disease? Psychosom Med. 1961;23:18-22.

Fogel B. Interrelations between people and pets. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas, 1981.

Fried M. Grieving for a lost home. In: Duh LJ, editor. Psychic trauma. New York: Basic Books, 1967.

Fuller RL, Geis S. Communicating with the grieving family. J Fam Pract. 1985;21(2):139-144.

Goin MK, Burgoyne RW, Goin JM. Timeless attachment to a dead relative. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136:988-989.

Hackett TP. Recognizing and treating abnormal grief. Hosp Physician. 1974;1:49-54.

Helsing KJ, Szklo M. Mortality after bereavement. Am J Epidemiol. 1981;114:41-52.

Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of event scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:209-218.

Horowitz MJ. Depression after the death of a spouse. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:579.

Jacobs S, Hansen F, Kasl S, et al. Anxiety disorders in acute ber-eavement: risk and risk factors. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51:269-274.

Jacobs SC, Kosten TR, Kasl SV, et al. Attachment theory and multiple dimensions of grief. Omega. 1987;18:41-52.

Jones DR, Goldblatt PO. Cause of death in widow(er)s and spouses. J Biosoc Sci. 1987;19:107-121.

Jones DR, Goldblatt PO, Leon DA. Bereavement and cancer: some results using data on deaths of spouses from the Longitudinal Study of Office of Population Censuses and Surveys. Br Med J. 1984;298:461-464.

Jones R, Yates WR, Williams S, et al. Outcome for adjustment disorder with depressed mood: comparison with other mood disorders. J Affect Disord. 1999;55(1):55-61.

Kavanaugh DG. Towards a cognitive-behavioral intervention for adult grief reactions. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:373-383.

Kim K, Jacobs S. Pathologic grief and its relationship to other psychiatric disorders. J Affect Disord. 1991;21:257-263.

Kubler-Ross E. On death and dying. New York: MacMillan, 1969.

Lazarus RS. The costs and benefits of denial. In: Dohrenwend BS, Dohrenwend BP, editors. Stressful life events and their contexts. New York: Prodist, 1981.

Lehman D, Ellard J, Wortman C. Social support for the bereaved: recipients’ and providers’ perspectives on what is helpful. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54:438-446.

Lichtenthal WG, Cruess DG, Prigerson HG. A case for establishing complicated grief as a distinct mental disorder in DSM-V. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24(6):637-662.

Lieberman MA. Self-help groups and psychiatry. Am Psychiatr Assoc Annu Rev. 1986;5:744-760.

Lieberman MA, Videka-Sherman L. The impact of self-help groups on the mental health of widows and widowers. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1986;56:435-449.

Pasnau RO, Fawney FI, Fawney N. Role of the physician in bereavement. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1987;10:109-120.

Rosenblatt PC, Burns LH. Long term effects of perinatal loss. J Fam Iss. 1986;7:237-253.

Rynearson EK. Psychotherapy of pathologic grief: revisions and limitations. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1987;10:487-500.

Shapiro ER. Family bereavement and cultural diversity: a social developmental perspective. Fam Process. 1996;35(3):313-332.

Stern EM. Psychotherapy and the grieving patient. New York: Haworth, 1985.

Strain JJ, Newcorn J, Fulop G, et al. Adjustment disorder. In Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Talbott JA, editors: The American Psychiatric Press textbook of psychiatry, ed 3, Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1999.

Weisman AD, Stern TA. The patient with acute grief. In Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, editors: Massachusetts General Hospital guide to primary care psychiatry, ed 2, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

Zeitlin SV. Grief and bereavement. Prim Care. 2001;28(2):415-425.

Zisook S, DeVaul R. Unresolved grief. Am J Psychoanal. 1985;45(4):370-379.

Zisook S, Shuchter SR, Schuckit M. Factors in the persistence of unresolved grief among psychiatric outpatients. Psychosomatics. 1985;26:497-503.