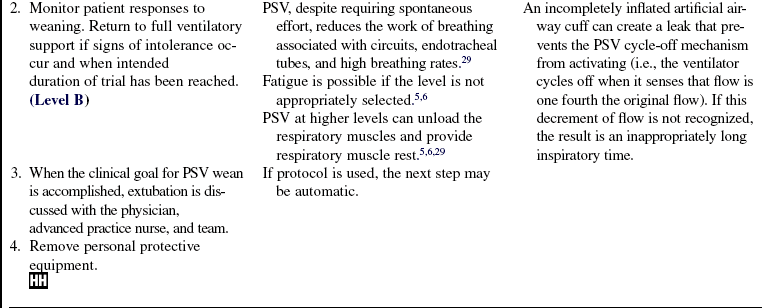

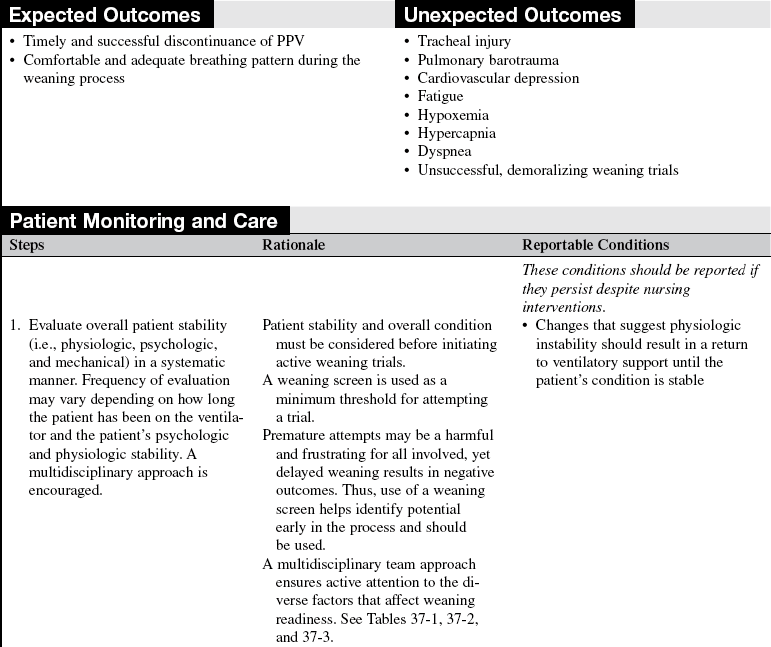

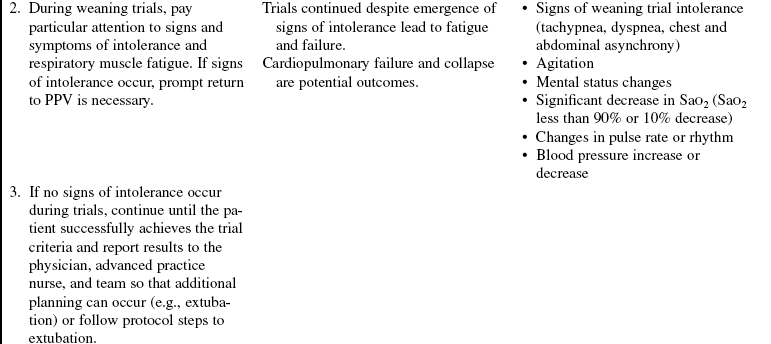

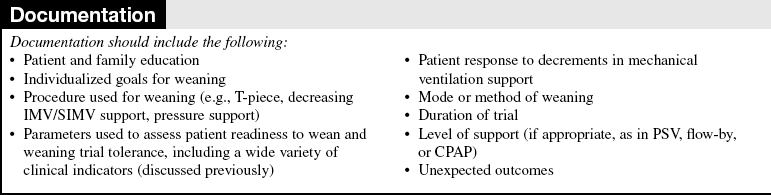

Weaning Process

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Knowledge and skills related to the care of patients on mechanical ventilation (e.g., airway management, suctioning, mechanical ventilator modes, blood gas interpretation) are necessary.

Short-Term versus Long-Term Mechanical Ventilation

• Short- versus long-term weaning is not clearly defined in the literature. Further, definitions vary in studies, which makes comparisons difficult. Regardless, patients who need mechanical ventilation for longer than 3 consecutive days clearly are at risk of needing mechanical ventilation for 12 to 14 days or longer.13 As duration of ventilation increases, the risk of iatrogenic (i.e., hospital-acquired) complications increases, all of which lengthen time on the ventilator. To that end, appropriate prophylaxis regimens, interventions designed to improve clinical factors that impede weaning, early assessment of weaning readiness, and protocol-directed weaning trials are essential to good outcomes.

Timing of Tracheostomy Tube Placement

• In some patients, especially those with anticipated long stays on the ventilator (spinal cord injury, progressive neurologic disorders, etc), a tracheostomy tube is placed early in the hospitalization. Other patients may also receive a tracheostomy, especially if they have had multiple unsuccessful attempts at weaning. These patients often have long stays on the ventilator, and weaning trials tend to be accomplished with progressively longer tracheostomy collar trials in comparison with other methods, as described subsequently.

• A recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) suggests that patients with early tracheostomy placement who are considered at risk of 2 weeks of mechanical ventilation have better outcomes if provided with a tracheostomy on day 2 of mechanical ventilation.40 Although the results are intriguing, they may be attributable to the fact that less sedation is necessary in patients with tracheostomies than in those with endotracheal tubes.37 As described subsequently, the use of sedation infusions is linked to prolonged ventilator times.

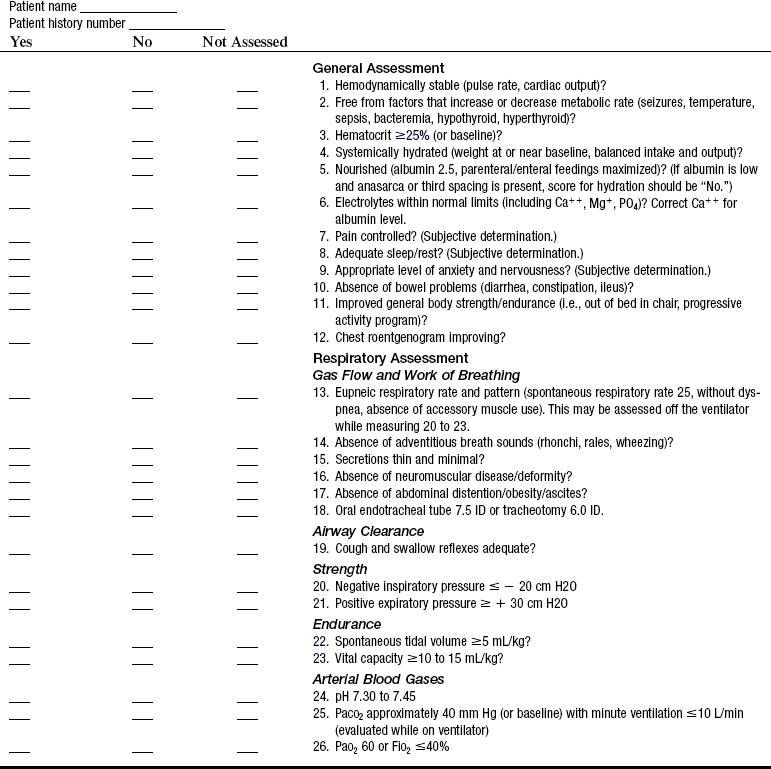

Weaning Assessment

• In the past, the assessment of weaning readiness was accomplished by determining whether or not the patient’s condition was stable, the reason for mechanical ventilation was resolved or improving, and the results of selected weaning criteria (or weaning indices) met threshold levels (Tables 37-1 and 37-2; see Procedure 36).10,41,50 Experts also noted that before weaning trials were initiated, attention to other clinical factors was essential.12,32 Clinical tools and checklists that ensure systematic attention to these factors help ensure good outcomes, an example of which is found in Table 37-3. In addition, prophylaxis regimes are necessary to prevent complications in patients on ventilation. These complications include ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), deep vein thrombosis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and sinusitis. Refer to Procedure 35 for a discussion of VAP prophylaxis and system-specific chapters for the others.

Table 37-1

Negative inspiratory pressure, ≤−20 cm H2O

Positive expiratory pressure, ≥+30 cm H2O

Spontaneous tidal volume, ≥5 mL/kg

Vital capacity, ≥10 to 15 mL/kg

Fraction of inspired oxygen, ≤50%

Minute ventilation, ≤10 L/min

Modified from Burns SM: Mechanical ventilation and weaning. In Kinney MR, et al, editors: AACN clinical reference for critical care nursing, ed 4, St Louis, 1998, Mosby.

Table 37-2

fx/Vt

Spontaneous respiratory frequency in 1 minute divided by Vt in liters

fx/Vt > 105 = weaning success

fx/Vt < 105 = weaning failure

fx, Frequency; Vt, tidal volume.

Data from Yang KL, Tobin JM: A prospective study of indexes predicting the outcome of trials of weaning from mechanical ventilation, N Engl J Med 324:1445-50, 1991.

Table 37-3

Burns Weaning Assessment Program (BWAP)*

Ca++, Calcium; Mg+, magnesium; ID, inside diameter; PO4, phosphate.

*To score the BWAP: Divide the number of “Yes” responses by 26.

• Unfortunately, weaning indices have proven to be disappointing predictors of a patient’s ability to wean.12,32,35,45 Most predictors focus on pulmonary-specific factors. Some investigators have combined indices and pulmonary factors to enhance the comprehensive nature of the indices and their predictive potential. In general, the indices are poor positive predictors (they do not tell us the patient will wean), but they are good negative predictors (they tell us the patient will not wean).13,32,35,45 Thus, use of the indices is not widespread. In fact, the various weaning indices are best used to evaluate the components from which they are designed (breathing pattern, respiratory muscle strength, etc.).

Weaning Process: Weaning Trial Protocols

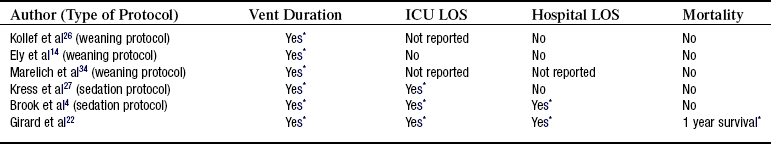

• The weaning process has changed dramatically as a result of a number of RCTs published in the late 1990s and early 2000s.7,14,19,26,34,48 The studies showed that protocol-directed spontaneous breathing trials greatly reduced ventilator duration. Additional studies with protocols linked tight glucose control and aggressive sedation management to ventilator duration, intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay (LOS), hospital LOS, and mortality.4,27,28,47 These protocols are briefly described.

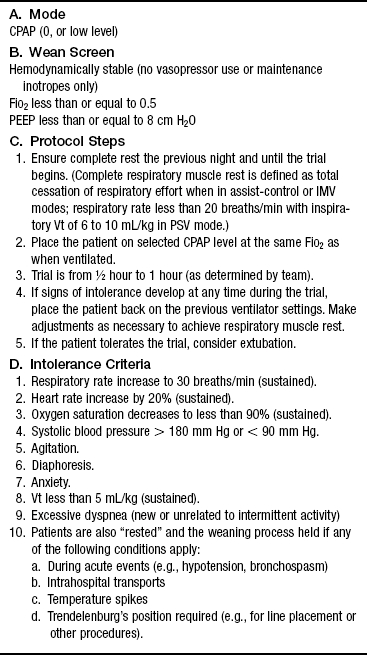

• Protocol-directed multidisciplinary weaning with “weaning screens” and short duration spontaneous breathing trials (SBTs) have been shown to be superior to “individualized” weaning processes.7,14,19,34,48 The use of the protocols decreases practice variation, perhaps the major reason for their effectiveness. Key to the success of the protocols is the use of the weaning screen, which requires that a minimum of clinical factor thresholds (e.g., hemodynamic stability, fraction of inspired oxygen [FiO2], positive end-expiratory pressure [PEEP] level) is met.14 This requirement ensures early and aggressive testing of patient readiness. Once the screen is passed, the patient is placed on a SBT for a short duration. One hour is generally adequate. If signs of intolerance emerge, the patient is returned to ventilatory support and a trial is reattempted at a later time as predetermined by the protocol. See Table 37-4 for an example of a protocol.

Weaning Process: Other Key Elements

• The association between sedation infusion use and negative clinical outcomes of patients on ventilation resulted in studies that tested the efficacy of methods to reduce the use of sedatives in these patients. Two RCTs used nurse-managed methods.4,27 In a study by Brook and colleagues,4 a sedation algorithm was used to direct sedation use. Kress and colleagues27 performed a daily sedation interruption. Both methods resulted in improved outcomes. Concerns about the potential negative impact of abrupt withdrawal of sedation in the critically ill were addressed. One study showed that those who had a daily interruption of sedation sustained significantly less psychologic harm and fewer complications than those who were not provided a daily sedation interruption.28,43 Additional studies linked sedation use (specifically benzodiazepines) to delirium and subsequent cognitive dysfunction in ICU patients on ventilation.16–18,39 Current guidelines on sedation use in critical care incorporate these elements in recommendations for management of both sedation and delirium.25

• Another RCT focused on the management of blood glucose in a surgical (mostly cardiac) patient population. In this study, a glucose level maintained at or below 110 g/dL (or 6.1 μmol/L) resulted in decreased sternal wound infections, shortened weaning times, and decreased ICU and hospital LOS. It also significantly reduced in-hospital mortality rates.47

• Recently, a multicenter RCT was accomplished that combined sedation interruption with a “wake-up and breathe” trial (i.e., SBT). In this study, patients assigned to the intervention (sedation interruption and wake up) had significantly more days of spontaneous breathing, earlier discharge from the ICU and hospital, and better 1-year survival rates than those in the control group.22 See Table 37-5 for summary of protocols for weaning and sedation use.

Adherence to Protocols

• Although the RCTs described show the importance of wean screens, SBTs, sedation management, and tight glucose control to weaning outcomes, studies on the adherence with the same are not encouraging. Adherence studies show that acceptance is low and that the protocols may not be realistic for use in everyday practice33,36,38,49, Given the increasing complexity of the clinical setting and the increasing shortage of ICU nurses and other healthcare professionals, rigorous protocols designed and implemented by study investigators are unlikely to be easily duplicated. We have much to learn in this area.

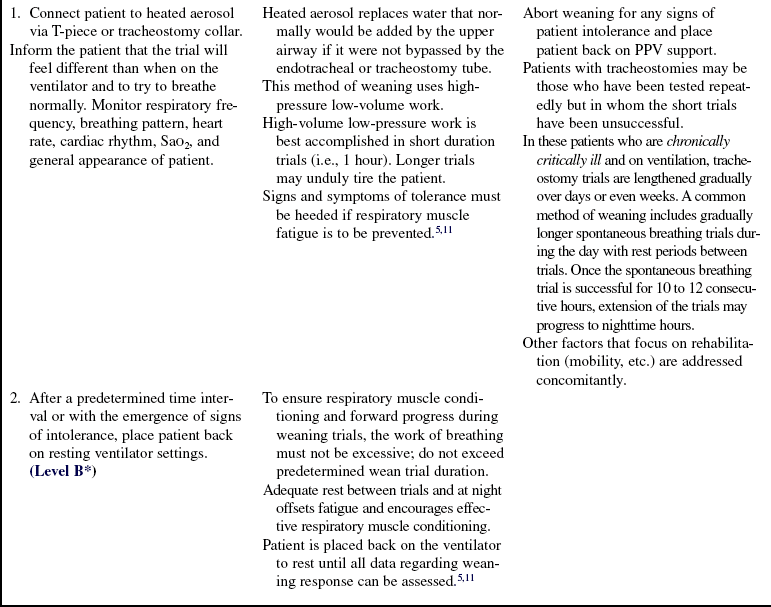

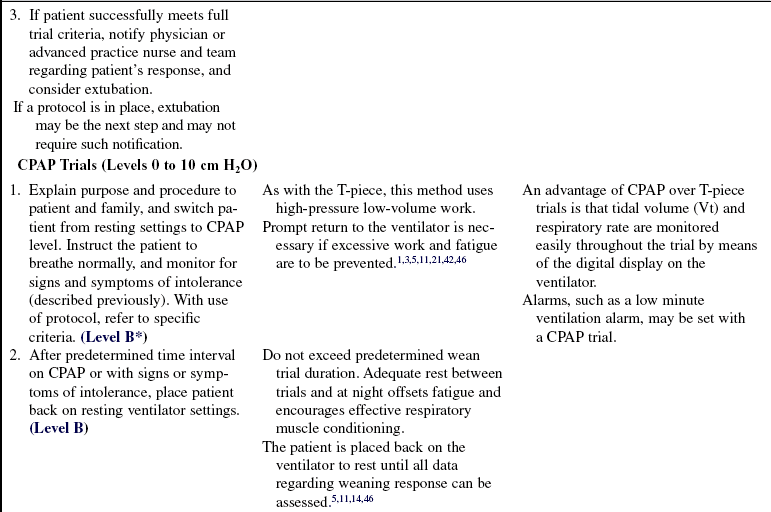

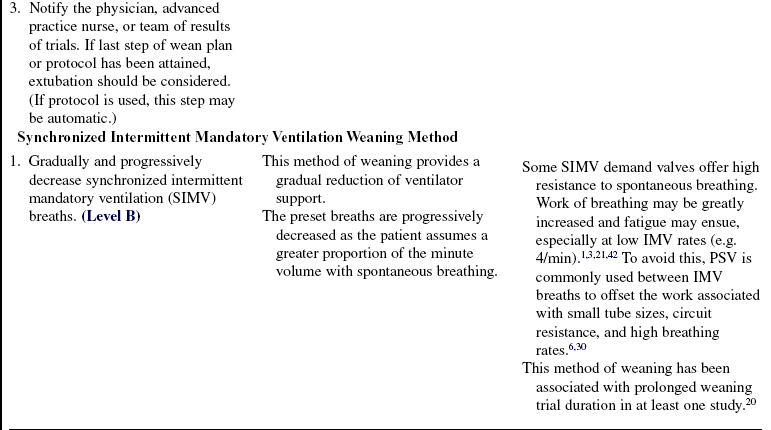

Modes for Weaning

• We have learned much about methods for weaning, but no specific weaning modes have emerged as superior.10,12,19,32,48 As previously noted, SBTs appear to be the best method; most of these use breathing through a T-piece or on the ventilator (with or without the addition of continuous positive airway pressure [CPAP] or other flow mechanisms, such as automatic tube compensation).14 Regardless, advocates of other modes such as pressure support ventilation (PSV) suggest they may be equally as effective. Although RCTs do not exist to support these hypotheses, evidence-based data exist that may provide rationale for the application of these modes.

Respiratory Muscle Fatigue, Work, Rest, and Conditioning

• The concept of respiratory muscle fatigue must be understood if it is to be prevented in the patient weaning from ventilation. All muscles may fatigue if work exceeds energy stores. Signs and symptoms of impending fatigue include dyspnea, tachypnea, chest-abdominal asynchrony, and increasing arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2, a late sign).2,11,46 Generally, fatigue may be prevented by avoiding premature or excessively long or difficult weaning trials.

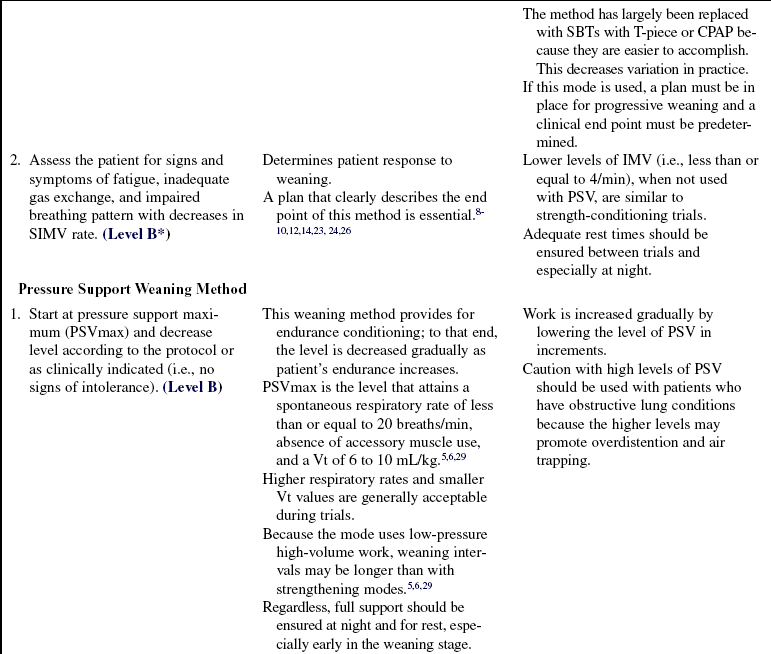

• The concepts of work, rest, and conditioning are useful to consider when selecting weaning modes and methods. Two classifications—high-pressure low-volume work and low-pressure high-volume work—are essential to the understanding of these three categories.

High-pressure low-volume work is associated with the use of a T-piece, CPAP, and low intermittent mandatory ventilation (IMV) rates. Generally, any method that requires that the patient breathe spontaneously (without inspiratory support) results in high-pressure low-volume work. This form of muscle conditioning is thought to build sarcomeres because it uses maximal muscle loading.30 Conditioning episodes are generally of short duration with full muscle rest between episodes. This type of conditioning is referred to as strengthening training.

High-pressure low-volume work is associated with the use of a T-piece, CPAP, and low intermittent mandatory ventilation (IMV) rates. Generally, any method that requires that the patient breathe spontaneously (without inspiratory support) results in high-pressure low-volume work. This form of muscle conditioning is thought to build sarcomeres because it uses maximal muscle loading.30 Conditioning episodes are generally of short duration with full muscle rest between episodes. This type of conditioning is referred to as strengthening training.

Low-pressure high-volume work is found with the use of PSV, in which inspiration is augmented. For any given pressure level, workload is less than if the patient were breathing spontaneously. At high levels of PSV, little work occurs, but as the level is reduced, muscle workload increases. Conditioning with PSV often is referred to as endurance conditioning; muscles are not worked to maximal effort. Instead, training focuses on gradual reductions of the level and maintenance of a specific level of work for progressively longer intervals.5,6,29–31

Low-pressure high-volume work is found with the use of PSV, in which inspiration is augmented. For any given pressure level, workload is less than if the patient were breathing spontaneously. At high levels of PSV, little work occurs, but as the level is reduced, muscle workload increases. Conditioning with PSV often is referred to as endurance conditioning; muscles are not worked to maximal effort. Instead, training focuses on gradual reductions of the level and maintenance of a specific level of work for progressively longer intervals.5,6,29–31

• With both types of conditioning, the goal is to progress the trials without inducing fatigue. To that end, rest is that level of ventilatory support that “unloads” the respiratory muscles. The level of support needed may differ with each patient; however, two basic concepts may be useful: 1, when signs of intolerance emerge, the trial is stopped and the patient is rested; and 2, application of rest varies with the weaning mode. For example, if the mode is PSV, then the PSV is increased to that level necessary to decrease the spontaneous rate (e.g., <20/min) and result in a synchronous comfortable breathing pattern. With high-pressure low-volume modes such as CPAP, the patient is returned to full ventilatory support.

Multidisciplinary Approaches

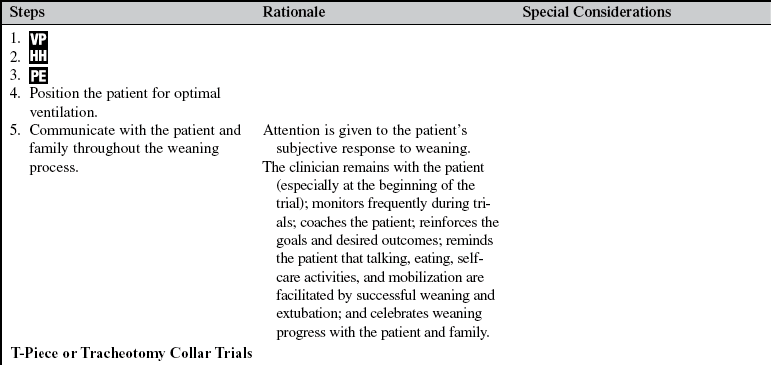

• Weaning is the process of gradual reduction of ventilatory support. To that end, a plan for weaning is determined by the multidisciplinary team and is applied and monitored carefully.8,9,14,15,23,24,34,44 The plan, whether it uses a protocol or consists of a more individualized written plan, should be available to all healthcare workers involved in the weaning process. Assessment of weaning potential may include checklists of factors important to weaning, such as the Burns Weaning Assessment Program (BWAP8–10; Table 37-3). In addition, prophylaxis for VAP and other potential complications associated with mechanical ventilation must be ensured.

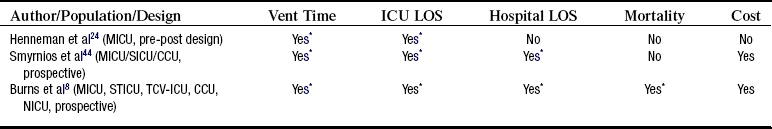

• Outcomes of system initiatives designed to ensure the comprehensive implementation of evidence-based interventions are promising. Advanced practice nurses were used to manage and monitor the conditions of patients in their care.8,9,24,44 The results suggest that use of such models of care are to be encouraged, but few have been developed, tested, and published (Table 37-6). Further, they tend to compare retrospective with prospective data elements, thus limiting the strength of the evidence. Unfortunately, RCTs of such system initiatives are unlikely to be accomplished in the future.

EQUIPMENT

• Weaning through the ventilator (e.g. CPAP, flow-by, automatic tube compensation ATC) requires that the digital readout of tidal volume and respiratory rate be assessable to the clinician for monitoring purposes

• If T-piece or tracheotomy collar setup is needed, a flow meter with a functional heated aerosol humidifier for the trials is necessary; the setup should have an in-line thermometer and a water trap

• Tracheotomy collar or T-piece adapters

• Personal protective equipment, as appropriate

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the procedures and reason for initiation of weaning.  Rationale: Anxiety is reduced when patients are prepared for the sensations they may experience during procedures.

Rationale: Anxiety is reduced when patients are prepared for the sensations they may experience during procedures.

• Reassure the patient of the nurse’s or the therapist’s presence during initiation of weaning.  Rationale: Assurance of the caregiver’s support and monitoring decreases anxiety.

Rationale: Assurance of the caregiver’s support and monitoring decreases anxiety.

• Discuss the sensations the patient may experience, such as smaller lung inflations, dyspnea, and change or absence of ventilator sounds. Describe that weaning trials are a form of conditioning and do require effort. Some dyspnea is to be expected.  Rationale: Patients (in particular, patients who have been on prolonged positive-pressure ventilation [PPV] support) may report discomfort with resumption of spontaneous breathing.

Rationale: Patients (in particular, patients who have been on prolonged positive-pressure ventilation [PPV] support) may report discomfort with resumption of spontaneous breathing.

• Encourage the patient to relax and breathe comfortably.  Rationale: Relaxation decreases muscle tension.

Rationale: Relaxation decreases muscle tension.

• Assure the patient and family that rapid return to ventilatory support will be accomplished if the patient becomes excessively dyspneic, becomes anxious, or exhibits untoward physiologic changes (e.g., desaturation; blood pressure, heart rate, and rhythm changes; diaphoresis).  Rationale: For trust to develop, the patient and family must believe that the nurse will not allow the trials to harm the patient.

Rationale: For trust to develop, the patient and family must believe that the nurse will not allow the trials to harm the patient.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Regular evaluation of factors that impede weaning in conjunction with factors that measure respiratory muscle strength, endurance, and gas exchange is necessary to ensure that all factors are being addressed appropriately (see Tables 37-1, 37-2, and 37-3).  Rationale: Improvement of factors that impede weaning is essential to the attainment of positive outcomes.

Rationale: Improvement of factors that impede weaning is essential to the attainment of positive outcomes.

• Assess progress toward achievement of individual short-term goals frequently.  Rationale: Successful weaning may be achieved within a short time (1/2 to 2 hours) if patient response is monitored closely and interventions are applied in tandem with patient response.

Rationale: Successful weaning may be achieved within a short time (1/2 to 2 hours) if patient response is monitored closely and interventions are applied in tandem with patient response.

• In patients who need mechanical ventilation for very long times (and often need a tracheostomy), assessment of daily progress toward achievement of individual long-term goals is important, in collaboration with the physician, respiratory therapist, patient, and family, as appropriate.  Rationale: Successful weaning may be achieved within days to weeks in these patients if patient response is methodically evaluated and interventions are applied in tandem with patient response.

Rationale: Successful weaning may be achieved within days to weeks in these patients if patient response is methodically evaluated and interventions are applied in tandem with patient response.

• Observe breathing pattern and note symptoms of dyspnea in response to decrements in PPV support. Other signs of fatigue include the following:

Rationale: These are signs and symptoms of potential or actual respiratory muscle fatigue. Interventions to offset the work of breathing are necessary.

Rationale: These are signs and symptoms of potential or actual respiratory muscle fatigue. Interventions to offset the work of breathing are necessary.

• Note whether the patient experiences changes in level of consciousness or nonverbal behavior and has symptoms of dyspnea or fatigue.  Rationale: Work of breathing may be such that the patient is maintaining an adequate breathing pattern and gas exchange at the moment but does not have sufficient reserves to continue expending energy to breathe. Patient exhaustion during weaning results in psychologic and physiologic delays in the weaning progress.

Rationale: Work of breathing may be such that the patient is maintaining an adequate breathing pattern and gas exchange at the moment but does not have sufficient reserves to continue expending energy to breathe. Patient exhaustion during weaning results in psychologic and physiologic delays in the weaning progress.

• Assess arterial blood gases as needed.  Rationale: Although frequent arterial blood gas assessments are rarely necessary during weaning if active attention is paid to signs and symptoms of intolerance, arterial blood gases are the only definitive method of evaluating efficiency of gas exchange. Evaluate of PaCO2 is especially important with spontaneous breathing if rapid return to increased ventilatory settings is not part of the plan or if dramatic changes in the patient’s condition are seen. PaCO2 is the definitive indicator of the adequacy of ventilation. PaCO2 (and pH) within the patient’s normal physiologic range indicates that the patient’s spontaneous ventilation is adequate. Weaning protocols are extremely helpful in that they identify intolerance criteria so that if they should emerge, return to ventilatory support may be prompt.

Rationale: Although frequent arterial blood gas assessments are rarely necessary during weaning if active attention is paid to signs and symptoms of intolerance, arterial blood gases are the only definitive method of evaluating efficiency of gas exchange. Evaluate of PaCO2 is especially important with spontaneous breathing if rapid return to increased ventilatory settings is not part of the plan or if dramatic changes in the patient’s condition are seen. PaCO2 is the definitive indicator of the adequacy of ventilation. PaCO2 (and pH) within the patient’s normal physiologic range indicates that the patient’s spontaneous ventilation is adequate. Weaning protocols are extremely helpful in that they identify intolerance criteria so that if they should emerge, return to ventilatory support may be prompt.

• Assess end-tidal carbon dioxide (PetCO2) levels.  Rationale: PetCO2 levels are best used to trend CO2 levels. It is important to know the PaCO2 level that corresponds to the PetCO2 level to use the PetCO2 values most efficiently. Remember that the PetCO2 values vary depending on the size of the breath. Larger tidal volume breaths provide more accurate values; the PaCO2 PetCO2– difference is less than when the tidal volumes are small. With small tidal volumes, there is more dead space ventilation and the PaCO2 PetCO2– difference is larger, which makes accurate trending difficult. This is especially the case during a spontaneous breathing trial when breath size varies. See Procedure 15 on PetCO2 for more in-depth information.

Rationale: PetCO2 levels are best used to trend CO2 levels. It is important to know the PaCO2 level that corresponds to the PetCO2 level to use the PetCO2 values most efficiently. Remember that the PetCO2 values vary depending on the size of the breath. Larger tidal volume breaths provide more accurate values; the PaCO2 PetCO2– difference is less than when the tidal volumes are small. With small tidal volumes, there is more dead space ventilation and the PaCO2 PetCO2– difference is larger, which makes accurate trending difficult. This is especially the case during a spontaneous breathing trial when breath size varies. See Procedure 15 on PetCO2 for more in-depth information.

• Assess oxygenation indices (see Procedure 33) during trials: arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) or arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2).  Rationale: SaO2 is a real-time continuous indicator of oxygenation during weaning trials and should be monitored continually. A saturation of greater than or equal to 90% generally indicates oxygenation adequacy. PaO2 is the definitive indicator of the adequacy of oxygenation and, in some cases, is required. A PaO2 within the patient’s normal physiologic range indicates that the patient’s oxygenation is adequate with spontaneous breathing. Generally, PaO2 greater than 60 mm Hg and SaO2 greater than or equal to 90% on a fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of less than or equal to 0.4 is acceptable during trials.

Rationale: SaO2 is a real-time continuous indicator of oxygenation during weaning trials and should be monitored continually. A saturation of greater than or equal to 90% generally indicates oxygenation adequacy. PaO2 is the definitive indicator of the adequacy of oxygenation and, in some cases, is required. A PaO2 within the patient’s normal physiologic range indicates that the patient’s oxygenation is adequate with spontaneous breathing. Generally, PaO2 greater than 60 mm Hg and SaO2 greater than or equal to 90% on a fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of less than or equal to 0.4 is acceptable during trials.

• Assess patient anxiety level.  Rationale: Resumption of spontaneous breathing may cause anxiety, particularly in patients who have been on prolonged PPV support. Encouragement is necessary, in addition to assurance that prompt return to ventilatory support will be accomplished, if the patient becomes excessively tired, anxious, or otherwise distressed. Patients must trust that the healthcare workers will address their concerns competently and rapidly during weaning trials.

Rationale: Resumption of spontaneous breathing may cause anxiety, particularly in patients who have been on prolonged PPV support. Encouragement is necessary, in addition to assurance that prompt return to ventilatory support will be accomplished, if the patient becomes excessively tired, anxious, or otherwise distressed. Patients must trust that the healthcare workers will address their concerns competently and rapidly during weaning trials.

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that the patient understands preprocedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: This communication evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

Rationale: This communication evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

• Address factors that are impeding wean potential. These factors may include pH level, hemodynamic stability, electrolytes, strength, endurance, mobility, nutrition, and fluid status, to name a few. A systematic approach with use of a checklist helps avoid variation in practice.  Rationale: Weaning has been associated with the correction of a myriad of physiologic factors. Weaning is not solely dependent on respiratory muscle strength and endurance.

Rationale: Weaning has been associated with the correction of a myriad of physiologic factors. Weaning is not solely dependent on respiratory muscle strength and endurance.

• Establish weaning screen criteria.  Rationale: Weaning screen criteria are essential for the rapid and safe assessment of weaning trial readiness.

Rationale: Weaning screen criteria are essential for the rapid and safe assessment of weaning trial readiness.

• Wean trial duration should be set before beginning the trial.  Rationale: Prolonged SBTs may fatigue the patient and result in poor outcomes. All key bedside caregivers must be aware of the limits of the trial and when to stop should signs of intolerance emerge.

Rationale: Prolonged SBTs may fatigue the patient and result in poor outcomes. All key bedside caregivers must be aware of the limits of the trial and when to stop should signs of intolerance emerge.

References

![]() 1. Banner, MJ, Blanch, PB, Kirby, RR. Imposed work of breathing and methods of triggering a demand-flow continuous positive airway system. Crit Care Med. 1993; 21:183–190.

1. Banner, MJ, Blanch, PB, Kirby, RR. Imposed work of breathing and methods of triggering a demand-flow continuous positive airway system. Crit Care Med. 1993; 21:183–190.

![]() 2. Bellemare, F, Grassino, A. Evaluation of human diaphragm fatigue. J Appl Physiol. 1982; 53:206–1196.

2. Bellemare, F, Grassino, A. Evaluation of human diaphragm fatigue. J Appl Physiol. 1982; 53:206–1196.

3. Beydon, L, et al. Inspiratory work of breathing during spontaneous ventilation using demand valves and continuous flow systems. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988; 138:300–304.

![]() 4. Brook, AD, Ahrens, TS, Schaff, R, et al. Effect of a nursing-implemented sedation protocol on the duration of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 1999; 27:2609–2615.

4. Brook, AD, Ahrens, TS, Schaff, R, et al. Effect of a nursing-implemented sedation protocol on the duration of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 1999; 27:2609–2615.

![]() 5. Brochard, L, et al. Inspiratory pressure support prevents diaphragmatic fatigue during weaning from mechanical ventilation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989; 139:513–521.

5. Brochard, L, et al. Inspiratory pressure support prevents diaphragmatic fatigue during weaning from mechanical ventilation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989; 139:513–521.

![]() 6. Brochard, L, Pluskwa, F, Lemaire, F. Improved efficacy of spontaneous breathing with inspiratory pressure support. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987; 136:411–415.

6. Brochard, L, Pluskwa, F, Lemaire, F. Improved efficacy of spontaneous breathing with inspiratory pressure support. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987; 136:411–415.

![]() 7. Brochard, L, et al. Comparison of three methods of gradual withdrawal from ventilatory support during weaning from mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care. 1994; 150:896–903.

7. Brochard, L, et al. Comparison of three methods of gradual withdrawal from ventilatory support during weaning from mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care. 1994; 150:896–903.

![]() 8. Burns, SM, et al, Implementation of an institutional program to improve clinical and financial outcomes of patients requiring mechanical ventilation. one year outcomes and lessons learned. Crit Care Med 2003; 31:2752–2763.

8. Burns, SM, et al, Implementation of an institutional program to improve clinical and financial outcomes of patients requiring mechanical ventilation. one year outcomes and lessons learned. Crit Care Med 2003; 31:2752–2763.

![]() 9. Burns, SM, et al. Design, testing and results of an outcomes-managed approach to patients requiring prolonged ventilation. Am J Crit Care. 1998; 7:45–47.

9. Burns, SM, et al. Design, testing and results of an outcomes-managed approach to patients requiring prolonged ventilation. Am J Crit Care. 1998; 7:45–47.

10. Burns, SM, The science of weaning. when and how. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 2004; 16:379–386.

![]() 11. Cohen, CA, et al. Clinical manifestations of inspiratory muscle fatigue. Am J Med. 1982; 73:308–316.

11. Cohen, CA, et al. Clinical manifestations of inspiratory muscle fatigue. Am J Med. 1982; 73:308–316.

![]() 12. Cook, D, et al, Evidence report on criteria for weaning from mechanical ventilation. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Rockville, MD, 1999. [contract no. 290-970017].

12. Cook, D, et al, Evidence report on criteria for weaning from mechanical ventilation. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Rockville, MD, 1999. [contract no. 290-970017].

![]() 13. Douglas, SL, Daly, BJ, Gordon, N, et al, Survival and quality of life. short-term versus long-term ventilator patients. Crit Care Med 2002; 30:2655–2662.

13. Douglas, SL, Daly, BJ, Gordon, N, et al, Survival and quality of life. short-term versus long-term ventilator patients. Crit Care Med 2002; 30:2655–2662.

![]() 14. Ely, EW, et al. Effect on the duration of mechanical ventilation of identifying patients capable of breathing spontaneously. N Engl J Med. 1998; 335:1864–1869.

14. Ely, EW, et al. Effect on the duration of mechanical ventilation of identifying patients capable of breathing spontaneously. N Engl J Med. 1998; 335:1864–1869.

![]() 15. Ely, EW, Bennett, PA, Bowton, DL, et al. Large scale implementation of a respiratory therapist-driven protocol for ventilator weaning. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999; 159:439–446.

15. Ely, EW, Bennett, PA, Bowton, DL, et al. Large scale implementation of a respiratory therapist-driven protocol for ventilator weaning. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999; 159:439–446.

![]() 16. Ely, EW, Margolin, R, Francis, J, et al, Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients. validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU). Crit Care Med 2001; 29:1370–1379.

16. Ely, EW, Margolin, R, Francis, J, et al, Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients. validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU). Crit Care Med 2001; 29:1370–1379.

![]() 17. Ely, EW, Gautam, S, Margolin, R, et al. The impact of delirium in the intensive care unit on hospital length of stay. Intensive Care Med. 2001; 27:1892–1900.

17. Ely, EW, Gautam, S, Margolin, R, et al. The impact of delirium in the intensive care unit on hospital length of stay. Intensive Care Med. 2001; 27:1892–1900.

![]() 18. Ely, EW, Shintani, A, Truman, B, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004; 291:1753–1762.

18. Ely, EW, Shintani, A, Truman, B, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004; 291:1753–1762.

![]() 19. Esteban, A, et al. A comparison of four methods of weaning patients from mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 1995; 332:345–350.

19. Esteban, A, et al. A comparison of four methods of weaning patients from mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 1995; 332:345–350.

![]() 20. Esteban, A, et al, and the Spanish Lung Failure Collaborative Group. Modes of mechanical ventilation and weaninga national survey of Spanish hospitals. Chest 1994; 106:1188–1193.

20. Esteban, A, et al, and the Spanish Lung Failure Collaborative Group. Modes of mechanical ventilation and weaninga national survey of Spanish hospitals. Chest 1994; 106:1188–1193.

![]() 21. Gibney, NRT, Wilson, RS, Pontoppidan, H. Comparison of work of breathing on high gas flow and demand valve continuous positive airway pressure systems. Chest. 82, 1982.

21. Gibney, NRT, Wilson, RS, Pontoppidan, H. Comparison of work of breathing on high gas flow and demand valve continuous positive airway pressure systems. Chest. 82, 1982.

22. Girard, TD, Kress, JP, Fuchs, BD, et al, Efficacy and safety of a paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care (Awakening and Breathing Controlled trial). a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008; 371:126–134.

![]() 23. Grap, MJ, Strickland, D, Tormay, L, et al, Collaborative practice. development, implementation, and evaluation of a weaning protocol for patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Am J Crit Care 2003; 12:454–460.

23. Grap, MJ, Strickland, D, Tormay, L, et al, Collaborative practice. development, implementation, and evaluation of a weaning protocol for patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Am J Crit Care 2003; 12:454–460.

![]() 24. Henneman, E, et al. Using a collaborative weaning plan to decrease duration of mechanical ventilation and length of stay in the intensive care unit for patients receiving long-term mechanical ventilation. Am J Crit Care. 2002; 11:132–140.

24. Henneman, E, et al. Using a collaborative weaning plan to decrease duration of mechanical ventilation and length of stay in the intensive care unit for patients receiving long-term mechanical ventilation. Am J Crit Care. 2002; 11:132–140.

![]() 25. Jacobi, J, Fraser, GL, Coursin, DB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in the critically ill adult. Crit Care Med. 2002; 30:119–141.

25. Jacobi, J, Fraser, GL, Coursin, DB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in the critically ill adult. Crit Care Med. 2002; 30:119–141.

![]() 26. Kollef, MH, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of protocol-directed versus physician-directed weaning from mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 1997; 25:557–574.

26. Kollef, MH, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of protocol-directed versus physician-directed weaning from mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 1997; 25:557–574.

![]() 27. Kress, JP, Pohlman, AS, O’Conner, MF, et al. Daily interruption of sedative infusions in critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342:1471–1477.

27. Kress, JP, Pohlman, AS, O’Conner, MF, et al. Daily interruption of sedative infusions in critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342:1471–1477.

![]() 28. Kress, JP, Gehlbach, B, Lacy, M, et al. The long-term psychological effects of daily sedative interruption on critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003; 168:1457–1461.

28. Kress, JP, Gehlbach, B, Lacy, M, et al. The long-term psychological effects of daily sedative interruption on critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003; 168:1457–1461.

![]() 29. MacIntyre, NR. Respiratory function during pressure support ventilation. Chest. 1986; 89:677–683.

29. MacIntyre, NR. Respiratory function during pressure support ventilation. Chest. 1986; 89:677–683.

![]() 30. MacIntyre, NR, Weaning from mechanical ventilatory support. volume-assisting intermittent breaths versus pressure assisting every breath. Respir Care 1988; 33:121–125.

30. MacIntyre, NR, Weaning from mechanical ventilatory support. volume-assisting intermittent breaths versus pressure assisting every breath. Respir Care 1988; 33:121–125.

![]() 31. MacIntyre, NR. Ventilatory modes and mechanical ventilatory support. Crit Care Med. 1997; 25:1106–1107.

31. MacIntyre, NR. Ventilatory modes and mechanical ventilatory support. Crit Care Med. 1997; 25:1106–1107.

![]() 32. MacIntyre, NR, et al, Evidence-based guidelines for weaning and discontinuing ventilatory support. a collective task force facilitated by the American College of Chest Physicians; the American Association for Respiratory Care; and the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 2001; 120(6 Suppl):375S–395S.

32. MacIntyre, NR, et al, Evidence-based guidelines for weaning and discontinuing ventilatory support. a collective task force facilitated by the American College of Chest Physicians; the American Association for Respiratory Care; and the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 2001; 120(6 Suppl):375S–395S.

33. Malesker, MA, Foral, PA, McPhillips, AC, et al. An efficiency evaluation of protocols for tight glycemic control in intensive care units. Am J Crit Care. 2007; 16:589–598.

![]() 34. Marelich, GP, Murin, S, Battistela, F, et al, Protocol weaning of mechanical ventilation in medical and surgical patients by respiratory care practitioners and nurses. effect on weaning time and ventilator associated pneumonia. Chest 2000; 118:459–467.

34. Marelich, GP, Murin, S, Battistela, F, et al, Protocol weaning of mechanical ventilation in medical and surgical patients by respiratory care practitioners and nurses. effect on weaning time and ventilator associated pneumonia. Chest 2000; 118:459–467.

![]() 35. Meade, M, Guyatt, G, Cook, D, et al. Predicting success in weaning from mechanical ventilation. Chest. 2001; 120(6 Suppl):400S–424S.

35. Meade, M, Guyatt, G, Cook, D, et al. Predicting success in weaning from mechanical ventilation. Chest. 2001; 120(6 Suppl):400S–424S.

36. Metha, S, Burry, L, Fischer, S, et al. Canadian survey of the use of sedatives, analgesics, and neuromuscular blocking agents in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2006; 34:374–380.

37. Nieszkowska, A, Combes, A, Luyt, C, et al. Impact of tracheotomy on sedative administration, sedation level, and comfort of mechanically ventilated intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2005; 33:2527–2533.

38. Oeyen, SG, Hoste, EA, Roosens, CD, et al, Adherence to and efficacy and safety of an insulin protocol in the critically ill. a prospective observational study. AJCC 2007; 16:599–608.

39. Pandharipande, P, Shintani, A, Peterson, J, et al. Lorazapam is an independent risk factor for transitioning to delirium in intensive care unit patients. Anesthesiology. 2006; 104:21–26.

![]() 40. Rumbak, MJ, Newton, M, Truncale, T, et al. A prospective, randomized study comparing early percutaneous dilational tracheotomy to prolonged translaryngeal intubation (delayed tracheotomy) in critically ill medical patients. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32:1689–1694.

40. Rumbak, MJ, Newton, M, Truncale, T, et al. A prospective, randomized study comparing early percutaneous dilational tracheotomy to prolonged translaryngeal intubation (delayed tracheotomy) in critically ill medical patients. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32:1689–1694.

![]() 41. Sahn, SA, Lakshminarayan, S. Bedside criteria for discontinuation of mechanical ventilation. Chest. 1973; 63:1002–1005.

41. Sahn, SA, Lakshminarayan, S. Bedside criteria for discontinuation of mechanical ventilation. Chest. 1973; 63:1002–1005.

![]() 42. Sassoon, CSH, et al. Inspiratory muscle work of breathing during flow-by, demand-flow, and continuous-flow systems in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992; 145:1219–1222.

42. Sassoon, CSH, et al. Inspiratory muscle work of breathing during flow-by, demand-flow, and continuous-flow systems in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992; 145:1219–1222.

![]() 43. Schweickert, WD, Gehlbach, BK, Pohlman, AS, et al. Daily interruptions of sedative infusions and complications of critical illness in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32:1272–1276.

43. Schweickert, WD, Gehlbach, BK, Pohlman, AS, et al. Daily interruptions of sedative infusions and complications of critical illness in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32:1272–1276.

![]() 44. Smyrnios, NA, et al. Effects of a multifaceted, multidisciplinary, hospital-wide quality improvement program on weaning from mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2002; 30:1224–1230.

44. Smyrnios, NA, et al. Effects of a multifaceted, multidisciplinary, hospital-wide quality improvement program on weaning from mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2002; 30:1224–1230.

45. Tanios, MA, Nevins, ML, Hendra, KP, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the role of weaning predictors in clinical decision making. Crit Care Med. 2006; 34:2530–2535.

![]() 46. Tobin, MJ, et al. Konno-Mead analysis of ribcage-abdominal motion during successful and unsuccessful trials of weaning from mechanical ventilation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987; 135:1320–1328.

46. Tobin, MJ, et al. Konno-Mead analysis of ribcage-abdominal motion during successful and unsuccessful trials of weaning from mechanical ventilation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987; 135:1320–1328.

![]() 47. Van den Berghe G, Wouters, P, Weekers, F, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2001; 354:1359–1367.

47. Van den Berghe G, Wouters, P, Weekers, F, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2001; 354:1359–1367.

![]() 48. Vitacca, M, Vianello, A, Colombo, D, et al. Comparison of two methods for weaning COPD patients requiring mechanical ventilation for more than 15 days. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001; 164:225–230.

48. Vitacca, M, Vianello, A, Colombo, D, et al. Comparison of two methods for weaning COPD patients requiring mechanical ventilation for more than 15 days. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001; 164:225–230.

49. Weinert, CR, Calvin, AD. Epidemiology of sedation and sedation adequacy for mechanically ventilated patients in a medical and surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2007; 35:393–401.

![]() 50. Yang, KL, Tobin, JM. A prospective study of indexes predicting the outcome of trials of weaning from mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 1994; 324:1445–1450.

50. Yang, KL, Tobin, JM. A prospective study of indexes predicting the outcome of trials of weaning from mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 1994; 324:1445–1450.

Burns, SM. Mechanical ventilation and weaning. In: Carlson K, ed. AACN’s advanced critical care nursing. St Louis: Elsevier, 2009.

Burns, SM, Practice protocol. weaning from mechanical ventilationBurns S, ed.. AACN protocols for practice -series. care of the mechanically ventilated patient. ed 2. Jones and Bartlett, Sudbury, 2007.

Burns, SM. Weaning from mechanical ventilation. In Pierce LNB, ed. : Management of the mechanically ventilated patient, ed 2, St Louis: Elsevier, 2007.

Pierce, LNB, Management of the mechanically ventilated patient. ed 2. Elsevier, St Louis, 2007.

Tobin, MJ. Principles and practice of mechanical ventilation, ed 2. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2006.