Procedure 37 Minimally Invasive Exposure Techniques of the Lumbar Spine

Indications

Conditions requiring decompression of the lumbar spine, wherein a minimally invasive surgery (MIS) technique is desired

Conditions requiring decompression of the lumbar spine, wherein a minimally invasive surgery (MIS) technique is desired

Examination/Imaging

Although it is difficult to define the exact boundaries of a percutaneous, mini-open, or traditional “open” surgery, the application of less invasive spinal surgery principles is much more important than the length of the skin incision (Jaikumar et al, 2002; Lehman et al, 2005).

Although it is difficult to define the exact boundaries of a percutaneous, mini-open, or traditional “open” surgery, the application of less invasive spinal surgery principles is much more important than the length of the skin incision (Jaikumar et al, 2002; Lehman et al, 2005).

The most important aspect to the success of spinal surgery is proper patient selection.

The most important aspect to the success of spinal surgery is proper patient selection.

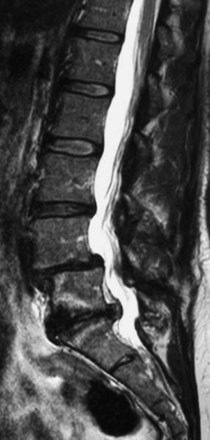

Before surgery, the surgeon should carefully study the imaging studies (plain radiographs, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] and/or computed tomography [CT]) and develop a surgical plan, including an optimal workflow for the procedure.

Before surgery, the surgeon should carefully study the imaging studies (plain radiographs, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] and/or computed tomography [CT]) and develop a surgical plan, including an optimal workflow for the procedure.

Evaluation of imaging is critical, because all relevant pathologic features must be visualized and addressed to achieve results comparable or superior to an open operation.

Evaluation of imaging is critical, because all relevant pathologic features must be visualized and addressed to achieve results comparable or superior to an open operation.

Patients with severe osteopenia, obesity, or intraabdominal contrast may be impossible to adequately image with the C-arm. If adequate fluoroscopic images cannot be obtained, an alternative surgical strategy should be employed.

Patients with severe osteopenia, obesity, or intraabdominal contrast may be impossible to adequately image with the C-arm. If adequate fluoroscopic images cannot be obtained, an alternative surgical strategy should be employed.

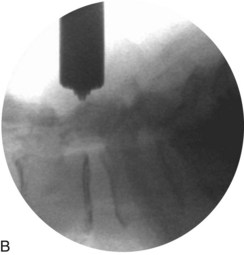

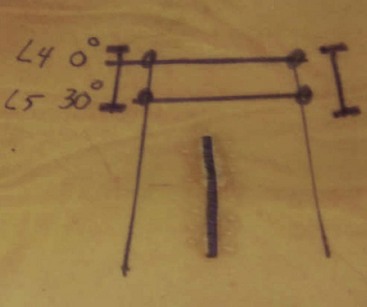

When setting up for percutaneous pedicle instrumentation, the vertebrae should be aligned so that, on an anteroposterior (AP) image, the spinous process is centered between the pedicles, and the superior end plate is parallel to the fluoroscopy beam (the true AP view) (Figure 37-1).

When setting up for percutaneous pedicle instrumentation, the vertebrae should be aligned so that, on an anteroposterior (AP) image, the spinous process is centered between the pedicles, and the superior end plate is parallel to the fluoroscopy beam (the true AP view) (Figure 37-1).

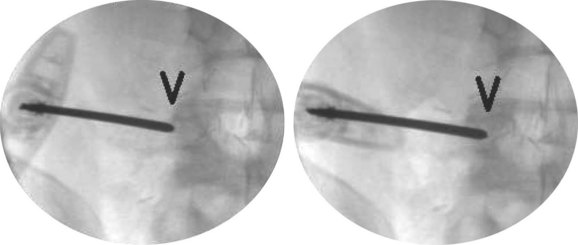

On the fluoroscopic lateral image, the pedicles should be superimposed, and only a single posterior cortex of the vertebral body should be seen (Figure 37-2, arrow). The edges of the superior end plate should be superimposed, forming a single radiopaque line.

On the fluoroscopic lateral image, the pedicles should be superimposed, and only a single posterior cortex of the vertebral body should be seen (Figure 37-2, arrow). The edges of the superior end plate should be superimposed, forming a single radiopaque line.

Treatment Options

• The alternative to any MIS procedure for the lumbar spine is traditional open surgery.

• With experience, MIS can be applied to essentially all degenerative conditions; however, because certain clinical situations may arise that preclude the completion of the surgery with a minimally invasive approach, the surgeon should always be prepared to extend the incision if required to adequately address the spinal pathology.

Surgical Anatomy

The radiographic position of all relevant anatomy should be undertaken before making the initial incision.

The radiographic position of all relevant anatomy should be undertaken before making the initial incision.

The incision should be positioned to allow optimal access to the surgical pathology.

The incision should be positioned to allow optimal access to the surgical pathology.

The skin and fascia should be sharply divided.

The skin and fascia should be sharply divided.

The muscle tissue should be gently traversed, working between the muscle planes or between muscle fascicles.

The muscle tissue should be gently traversed, working between the muscle planes or between muscle fascicles.

The tubular retractor should be docked to the spine to minimize the need to resect muscle tissues to visualize the bony anatomy.

The tubular retractor should be docked to the spine to minimize the need to resect muscle tissues to visualize the bony anatomy.

The bony landmarks should be identified before the resection of any bone.

The bony landmarks should be identified before the resection of any bone.

Care should be taken to preserve an adequate amount of the pars interarticularis and inferior articular process if a fusion of the operative level is not planned.

Care should be taken to preserve an adequate amount of the pars interarticularis and inferior articular process if a fusion of the operative level is not planned.

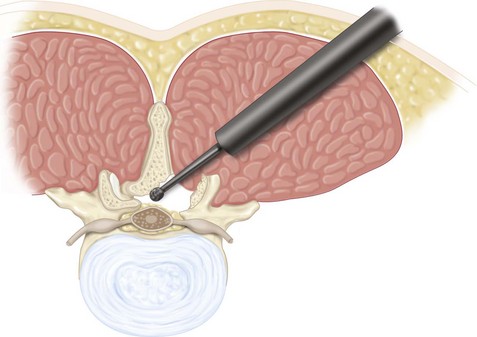

When working in the spinal canal, the epidural fat is a useful clue to localize the plane beneath the ligamentum flavum, adjacent to the dura.

When working in the spinal canal, the epidural fat is a useful clue to localize the plane beneath the ligamentum flavum, adjacent to the dura.

The pedicle is a key landmark to assist the surgeon in localizing the position within the spinal canal. By palpating the pedicle, the surgeon can gauge the amount of bony resection and can also localize migrated disk fragments.

The pedicle is a key landmark to assist the surgeon in localizing the position within the spinal canal. By palpating the pedicle, the surgeon can gauge the amount of bony resection and can also localize migrated disk fragments.

The exiting and traversing nerve root should be decompressed as needed, depending on the nature of the patient symptoms and pathology.

The exiting and traversing nerve root should be decompressed as needed, depending on the nature of the patient symptoms and pathology.

Surgical Anatomy Pearls

• Careful fluoroscopic localization of the surgical incision is mandatory before making the incision.

• A spinal needle inserted along the proposed trajectory of the surgical incision can be used to check the location of the incision using fluoroscopy.

• Careful palpation of surgical planes is useful before using a Kerrison instrument to remove bone from the region of the spinal canal.

Positioning

For posterior procedures (microdiskectomy, lumbar decompression, PLF, PLIF, TLIF etc.), the patient should be positioned prone on a radiolucent spinal table or frame.

For posterior procedures (microdiskectomy, lumbar decompression, PLF, PLIF, TLIF etc.), the patient should be positioned prone on a radiolucent spinal table or frame.

The abdomen should be free of compression (Lehman et al, 2005; Seldomridge and Phillips, 2005).

The abdomen should be free of compression (Lehman et al, 2005; Seldomridge and Phillips, 2005).

Careful padding of all vital and bony regions should be confirmed.

Careful padding of all vital and bony regions should be confirmed.

Access for fluoroscopy should be confirmed in the operative position.

Access for fluoroscopy should be confirmed in the operative position.

Access for the operative microscope should be confirmed.

Access for the operative microscope should be confirmed.

For anterior procedures, the abdomen should be widely draped with access from the xiphoid to the pubis.

For anterior procedures, the abdomen should be widely draped with access from the xiphoid to the pubis.

For lateral interbody fusion procedures (XLIF, DLIF) the patient should be secured in a “true” lateral position with a slight lateral bend to the lumbar region (away from the operative incision) to improve access to the lateral aspect of the vertebral body.

For lateral interbody fusion procedures (XLIF, DLIF) the patient should be secured in a “true” lateral position with a slight lateral bend to the lumbar region (away from the operative incision) to improve access to the lateral aspect of the vertebral body.

General Aspects to Posterior Tubular Retractor Surgery

The learning curve for MIS techniques must be acknowledged and planned for.

The learning curve for MIS techniques must be acknowledged and planned for.

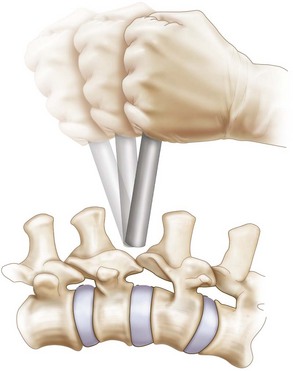

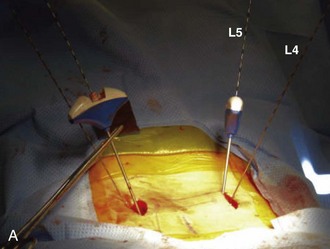

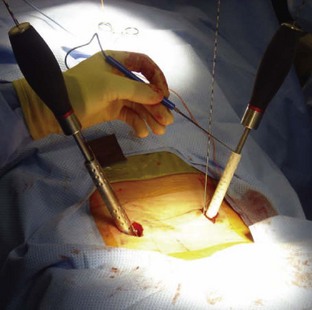

Reconstructive procedures (Figure 37-3) are more difficult compared with decompressive procedures and should be approached farther along the learning curve of the individual surgeon. Additional time should be allotted for surgical cases in the early portion of the surgeon’s learning curve.

Reconstructive procedures (Figure 37-3) are more difficult compared with decompressive procedures and should be approached farther along the learning curve of the individual surgeon. Additional time should be allotted for surgical cases in the early portion of the surgeon’s learning curve.

The first surgical step is to localize the precise site for all skin incisions using fluoroscopy (Seldomridge and Phillips, 2005).

The first surgical step is to localize the precise site for all skin incisions using fluoroscopy (Seldomridge and Phillips, 2005).

The use of an expandable tubular retractor system allows a more generous exposure but has the trade off of increased tissue dissection and soft tissue creep.

The use of an expandable tubular retractor system allows a more generous exposure but has the trade off of increased tissue dissection and soft tissue creep.

Although the instruments used for minimally invasive spine surgery (MISS) procedures are similar to those used with traditional open procedures, longer, bayoneted instruments are useful to ensure that visualization is not obscured by the surgeon’s hands.

Although the instruments used for minimally invasive spine surgery (MISS) procedures are similar to those used with traditional open procedures, longer, bayoneted instruments are useful to ensure that visualization is not obscured by the surgeon’s hands.

“Wanding” of the tubular retractor is an important technique that allows access outside the initial surgical exposure.

“Wanding” of the tubular retractor is an important technique that allows access outside the initial surgical exposure.

In addition to direct visualization through the retractor, tactile “feel” is also an important skill for the MIS spinal surgeon to develop and use.

In addition to direct visualization through the retractor, tactile “feel” is also an important skill for the MIS spinal surgeon to develop and use.

In the event of a dural laceration, direct suture repair is the authors’ preferred treatment strategy for most tears (Bosacco et al, 2001). However, others have reported successful management of minor dural tears by the use of sealants without direct repair, as long as there is no tendency for nerve rootlet extravasation.

In the event of a dural laceration, direct suture repair is the authors’ preferred treatment strategy for most tears (Bosacco et al, 2001). However, others have reported successful management of minor dural tears by the use of sealants without direct repair, as long as there is no tendency for nerve rootlet extravasation.

The risk of dural cutaneous fistula, resulting from the small “dead space” in the wound, is reduced with an MIS exposure compared with an open surgical procedure.

The risk of dural cutaneous fistula, resulting from the small “dead space” in the wound, is reduced with an MIS exposure compared with an open surgical procedure.

Procedure

Step 1

An MIS approach offers an excellent option for correcting localized spinal canal stenosis or treating herniated lumbar disks.

An MIS approach offers an excellent option for correcting localized spinal canal stenosis or treating herniated lumbar disks.

Simple decompressive surgery is generally straightforward and is an appropriate starting point for the novice MISS surgeon.

Simple decompressive surgery is generally straightforward and is an appropriate starting point for the novice MISS surgeon.

A bilateral lumbar decompression or “laminoplasty” technique can be used to address bilateral stenosis through a single unilateral skin incision.

A bilateral lumbar decompression or “laminoplasty” technique can be used to address bilateral stenosis through a single unilateral skin incision.

After the bone drilling is complete, the ligamentum flavum should be removed to allow direct visualization of the nerve roots and decompression of the dura.

After the bone drilling is complete, the ligamentum flavum should be removed to allow direct visualization of the nerve roots and decompression of the dura.

Step 1 Pearls

• Avoid using an overly large diameter tubular retractor for decompressive procedures, because this will push the surgeon away from the midline.

• The authors prefer to use a 14- to 18-mm diameter tube (outer diameter) for diskectomies and an 18- to 20-mm tube for stenosis decompression.

• Leave the ligamentum flavum intact during drilling of bone to protect the dura.

Step 2

Anterior lumbar interbody fusion

Anterior lumbar interbody fusion

Lateral transpsoas interbody fusion

Lateral transpsoas interbody fusion

Step 2 Pearls

• Penetration of the end plate during diskectomy should be avoided by the careful use of sharp instruments within the disk space.

• All cartilaginous material must be removed from the end plates to allow an optimal chance of achieving fusion.

• Avoid undersizing the interbody implants during interbody fusion, which may reduce stability of the construct and allow migration of the implant.

• Any overhanging bone that reduces the opening to the disk space should be removed to allow optimal clearance of disk material and proper sizing of the interbody implant.

Step 2 Pitfalls

• Take great care to avoid violation of the anterior annulus, which risks a major vascular injury.

• Be aware that, rarely, a conjoined nerve root may prevent safe access to the disk space when performing a TLIF or PLIF approach. In such a situation, an alternative fusion method should be undertaken.

Step 3: Instrumentation

Minimally invasive spinal instrumentation has been simplified with the advent of percutaneous cannulated pedicle screw systems.

Minimally invasive spinal instrumentation has been simplified with the advent of percutaneous cannulated pedicle screw systems.

Surgeons should familiarize themselves with the specifics of the instrumentation system before the procedure.

Surgeons should familiarize themselves with the specifics of the instrumentation system before the procedure.

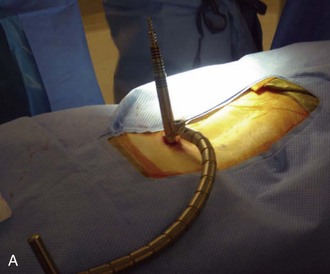

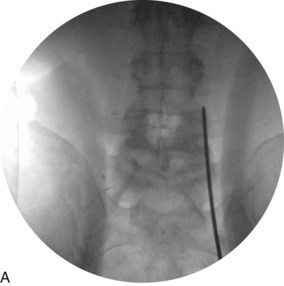

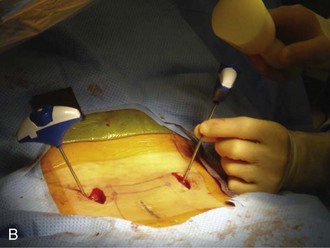

Percutaneous pedicle screw instrumentation begins with obtaining a true AP fluoroscopic image of the vertebra (Figure 37-9, A).

Percutaneous pedicle screw instrumentation begins with obtaining a true AP fluoroscopic image of the vertebra (Figure 37-9, A).

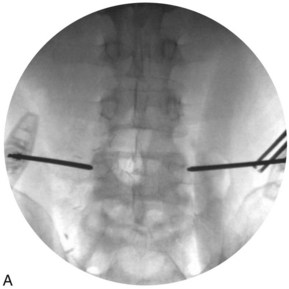

Incisions should be localized about 1 cm lateral to the lateral margin of the pedicle visualized on the AP image (Figure 37-9, B) (Lehman et al, 2005; Seldomridge and Phillips, 2005).

Incisions should be localized about 1 cm lateral to the lateral margin of the pedicle visualized on the AP image (Figure 37-9, B) (Lehman et al, 2005; Seldomridge and Phillips, 2005).

Preexisting incisions used for a TLIF or PLIF procedure can generally be used for the placement of pedicle screw fixation.

Preexisting incisions used for a TLIF or PLIF procedure can generally be used for the placement of pedicle screw fixation.

A Jamshidi needle is introduced through the skin incision to dock on the bone directly over the lateral boarder of the pedicle at the 3 o’clock (right) and 9 o’clock (left) position.

A Jamshidi needle is introduced through the skin incision to dock on the bone directly over the lateral boarder of the pedicle at the 3 o’clock (right) and 9 o’clock (left) position.

After confirming that the tip of the needle is properly positioned (Figure 37-10, A), the tip of the needle is seated a few millimeters into the bone with gentle mallet taps (Figure 37-10, B).

After confirming that the tip of the needle is properly positioned (Figure 37-10, A), the tip of the needle is seated a few millimeters into the bone with gentle mallet taps (Figure 37-10, B).

The position of the needle tip is again confirmed with AP fluoroscopy.

The position of the needle tip is again confirmed with AP fluoroscopy.

Next, the needle shaft is marked 20 mm above the skin edge.

Next, the needle shaft is marked 20 mm above the skin edge.

Holding the needle shaft parallel to the end-plate shadow, with about 10 degrees of lateral to medial angulation, the needle is tapped through the pedicle, until the mark on the needle shaft reaches the skin edge (at this point, the needle tip has traversed the isthmus of the pedicle).

Holding the needle shaft parallel to the end-plate shadow, with about 10 degrees of lateral to medial angulation, the needle is tapped through the pedicle, until the mark on the needle shaft reaches the skin edge (at this point, the needle tip has traversed the isthmus of the pedicle).

An AP image is again taken to assess the position of the tip of the needle, which should lie approximately

An AP image is again taken to assess the position of the tip of the needle, which should lie approximately  to

to  of the distance (from medial to lateral) across the pedicle (Figure 37-11).

of the distance (from medial to lateral) across the pedicle (Figure 37-11).

A guidewire is inserted through the needle shaft and advanced about 15 mm into the vertebral body.

A guidewire is inserted through the needle shaft and advanced about 15 mm into the vertebral body.

The Jamshidi needle should advance smoothly as it is tapped through the pedicle. If hard bone is encountered, the tip of the needle is most likely medial and striking the cortical surface of the superior articular process. In such an event, the tip of the needle should be repositioned with a more lateral starting point to avoid penetration of the facet joint.

The Jamshidi needle should advance smoothly as it is tapped through the pedicle. If hard bone is encountered, the tip of the needle is most likely medial and striking the cortical surface of the superior articular process. In such an event, the tip of the needle should be repositioned with a more lateral starting point to avoid penetration of the facet joint.

The guidewire should also encounter cancellous bone at the base of the needle shaft. This has a characteristic “feel” that should be confirmed by the surgeon before insertion of the guidewire.

The guidewire should also encounter cancellous bone at the base of the needle shaft. This has a characteristic “feel” that should be confirmed by the surgeon before insertion of the guidewire.

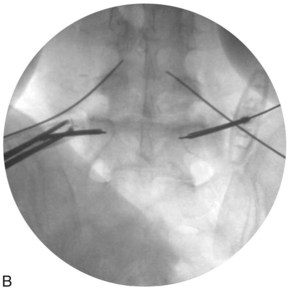

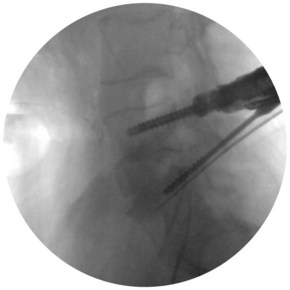

Guidewires are inserted through the Jamshidi needle (Figure 37-12, A and B).

Guidewires are inserted through the Jamshidi needle (Figure 37-12, A and B).

Cannulated instruments, such as awls and taps, are used to prepare the pedicle for screw insertion.

Cannulated instruments, such as awls and taps, are used to prepare the pedicle for screw insertion.

Electromyography can be used to test the tap and ensure that it has not breeched the cortex (Figure 37-13).

Electromyography can be used to test the tap and ensure that it has not breeched the cortex (Figure 37-13).

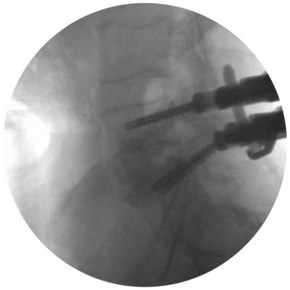

Lateral fluoroscopy should be used to monitor the depth of instruments inserted over the guidewires (Figure 37-14).

Lateral fluoroscopy should be used to monitor the depth of instruments inserted over the guidewires (Figure 37-14).

The guidewire should always be held when passing instruments over it, to prevent advancement of the guidewire or inadvertent removal.

The guidewire should always be held when passing instruments over it, to prevent advancement of the guidewire or inadvertent removal.

After tapping the pedicle holes with a cannulated tap, the cannulated pedicle screws can be placed.

After tapping the pedicle holes with a cannulated tap, the cannulated pedicle screws can be placed.

The rod can then be introduced and locked into place (Figures 37-15 and 37-16).

The rod can then be introduced and locked into place (Figures 37-15 and 37-16).

Final AP and lateral fluoroscopy (Figure 37-17) should confirm the fusion construct to be in an acceptable position.

Final AP and lateral fluoroscopy (Figure 37-17) should confirm the fusion construct to be in an acceptable position.

The authors prefer to use subcuticular resorbable sutures to close the wound, resulting in a desirable cosmetic result (Figure 37-18).

The authors prefer to use subcuticular resorbable sutures to close the wound, resulting in a desirable cosmetic result (Figure 37-18).

Step 3 Pearls

• Obtaining a true AP fluoroscopic image parallel to the superior end plate of the vertebral body is paramount for the success of percutaneous screw placement.

• By marking the depth of insertion through the pedicle on the Jamshidi needle, the surgeon can safely insert the guidewires without having to switch multiple times between the AP and lateral fluoroscopy images.

Postoperative Care and Expected Outcomes

Postoperative care is similar to traditional open lumbar surgery. However, patients generally have less postoperative pain and are able to mobilize earlier in the postoperative period, compared with open surgery.

Postoperative care is similar to traditional open lumbar surgery. However, patients generally have less postoperative pain and are able to mobilize earlier in the postoperative period, compared with open surgery.

The authors encourage mobilization and ambulation on the day of surgery and discharge when patients are comfortable on oral medications.

The authors encourage mobilization and ambulation on the day of surgery and discharge when patients are comfortable on oral medications.

Although all of the complications of open spinal surgery are still applicable to MIS spinal procedures, certain complications, such as infection and heavy bleeding, are much less frequent with MIS procedures.

Although all of the complications of open spinal surgery are still applicable to MIS spinal procedures, certain complications, such as infection and heavy bleeding, are much less frequent with MIS procedures.

Optimal long-term outcome depends on proper patient selection and careful, adequate performance of the operation.

Optimal long-term outcome depends on proper patient selection and careful, adequate performance of the operation.

Bosacco SJ, Gardner MJ, Guille JT. Evaluation and treatment of dural tears in lumbar spine surgery: a review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;389:238-247.

German JW, Foley KT. Minimal access surgical techniques in the management of the painful lumbar motion segment. Spine. 2005;30(Suppl):S52-S59.

Jaikumar S, Kim DH, Kam AC. History of minimally invasive spine surgery. Neurosurgery. 2002;51(Suppl):S1-14.

Khoo LT, Palmer S, Laich DT, Fessler AG. Minimally invasive percutaneous posterior lumbar interbody fusion. Neurosurgery. 2002;51(Suppl):S166-S171.

Lehman RA, Vaccaro AR, Bartagnoli R, Kuklo TR. Standard and minimally invasive approaches to the spine. Orthop Clin North Am. 2005;36:281-292.

Seldomridge JA, Phillips FM. Minimally invasive spine surgery. Am J Orthop. 2005;34:224-232.

Tafazal SI, Sell PJ. Incidental durotomy in lumbar spine surgery: incidence and management. Eur Spine J. 2004;14:287-290.

Wu RH, Fraser JF, Härtl R. Minimal access versus open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: meta-analysis of fusion rates. Spine. 2010;35:2273-2281.