Standard Weaning Criteria: Negative Inspiratory Force or Pressure, Positive Expiratory Pressure, Spontaneous Tidal Volume, Vital Capacity, and Rapid Shallow Breathing Index

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Weaning criteria emerged in the late 1970s in an attempt to identify patient potential for successful extubation. Although these “standard weaning criteria,” which included negative inspiratory force or pressure (NIF or NIP), positive expiratory pressure (PEP), spontaneous tidal volume (SVt), and vital capacity (VC), were used widely over the years to test weaning readiness, they gradually grew out of favor because they did not perform well as predictors, especially in disparate categories of patient conditions.2 Two systematic reviews evaluated the weaning process and concluded that weaning criteria (also known as predictors or indices) did not predict weaning.4,8 They were found to be good negative predictors (i.e., that the weaning attempt would be unsuccessful) but poor positive predictors (i.e., that the weaning attempt would be successful).1,9,11,12 Regardless, the criteria do provide information about respiratory muscle strength and endurance and may be especially helpful in following trends in gains in strength and endurance in patients with debilitated weak conditions or in patients with myopathies. The criteria also may help in evaluation of respiratory muscle fatigue (see Procedure 37).

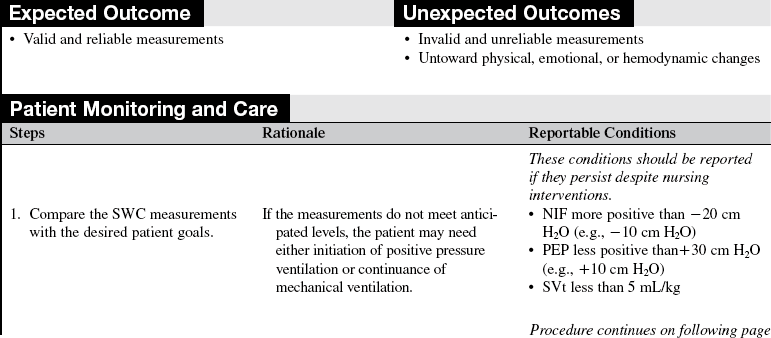

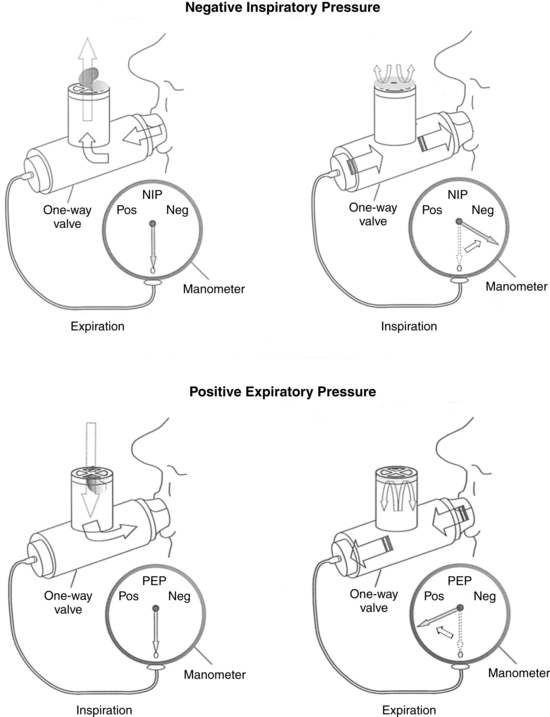

• Negative inspiratory force (NIF) also is called negative inspiratory pressure (NIP) or sometimes maximal inspiratory pressure (MIP). The measurement of NIF is effort independent (the patient does not have to actively cooperate) and is considered the most reliable of the standard weaning criteria (SWC). NIF is a measure of inspiratory respiratory muscle strength. It is a strong negative predictor but a poor positive predictor.1,4,12 The most common threshold cited for NIF is less than or equal to –20 cm H2O. Because this measurement is non–effort dependent, with good technique (see the procedure), the value is reliable unless central drive is impaired. For example, with sedation, a cuff leak, or respiratory muscle fatigue, the value may be adversely affected.

• Positive expiratory pressure (PEP) is effort dependent and requires that the patient cooperate fully to obtain a reliable value. PEP is a measure of expiratory muscle strength and ability to cough. The threshold for PEP is greater than or equal to +30 cm H2O.

• Spontaneous tidal volume (SVt) is a measure of respiratory muscle endurance. The threshold for SVt is greater than or equal to 5 mL/kg of body weight. When muscles fatigue, the compensatory breathing pattern is rapid and shallow. As a result, investigators have combined SVt and spontaneous respiratory rate (fx) in a ratio called the rapid shallow breathing index (fx/Vt).13

• The fx/Vt index threshold associated with success is less than or equal to 105. This threshold is calculated by obtaining the spontaneous respiratory rate and dividing it by the Vt in liters.13 In elderly medical patients, the threshold is less than or equal to 130.7

• Vital capacity (VC) is also a measure of respiratory muscle endurance or reserve or both. A fatigued patient is unable to triple or even double the size of a breath. The threshold for VC is greater than or equal to 10 to 15 mL/kg (at least two to three times SVt).

• Vital capacity may be especially helpful in patients with neurologic conditions like myasthenia or Guillain-Barré syndrome. In these patients, a decrease in the VC suggests loss of reserve and impending respiratory muscle failure.3

• All SWC are best used in combination with other assessment data to determine the appropriateness of weaning trials or extubation.2,4,8,11,12

• Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were conducted to determine when and how best to wean patients from mechanical ventilatory support. The studies showed the efficacy and safety of multidisciplinary protocols with use of a “wean screen” (a set of discrete criteria that suggest stability, such as a fraction of inspired oxygen [FiO2] less than 0.50, positive end-expiratory pressure [PEEP] less than 8 cm H2O, no vasopressor use, etc.) followed by a carefully monitored spontaneous breathing trial (SBT) in attaining positive outcomes.5,6,10 These study results have greatly obviated reliance on traditional weaning criteria as predictive tools.

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Inform the patient and family about the patient’s respiratory status, changes in therapy, and how to interpret the changes. If the patient or a family member requests specific information about the measurements, explain the relationship between these measurements and respiratory muscle strength and endurance.  Rationale: Most patients and families are less concerned with the diagnostic and therapeutic details and more concerned with how the patient’s condition is progressing overall. However, patients and families readily grasp the concepts of muscle strength and endurance. They may wish to follow the patient’s progress by monitoring the results of the tests over time. If appropriate, the family can be recruited to help encourage the patient to provide a maximal effort during measurements.

Rationale: Most patients and families are less concerned with the diagnostic and therapeutic details and more concerned with how the patient’s condition is progressing overall. However, patients and families readily grasp the concepts of muscle strength and endurance. They may wish to follow the patient’s progress by monitoring the results of the tests over time. If appropriate, the family can be recruited to help encourage the patient to provide a maximal effort during measurements.

• Discuss the sensations the patient may experience, such as transient shortness of breath and fatigue.  Rationale: Knowledge of anticipated sensory experiences reduces anxiety and distress.

Rationale: Knowledge of anticipated sensory experiences reduces anxiety and distress.

• Explain to the patient the importance of cooperation and maximal effort to achieve valid and reliable measurements.  Rationale: Information about the patient’s therapy, including the rationale, is cited consistently as an important need of patients and family members.

Rationale: Information about the patient’s therapy, including the rationale, is cited consistently as an important need of patients and family members.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Assess for the signs and symptoms of inadequate ventilation:

Increasing carbon dioxide tension in expired air or arterial blood

Increasing carbon dioxide tension in expired air or arterial blood

Shallow or irregular respirations

Shallow or irregular respirations

Restlessness, confusion, lethargy

Restlessness, confusion, lethargy

Increasing or decreasing arterial blood pressure beyond a predetermined threshold level

Increasing or decreasing arterial blood pressure beyond a predetermined threshold level

Tachycardia or bradycardia beyond an predetermined threshold level

Tachycardia or bradycardia beyond an predetermined threshold level

Rationale: Inadequate ventilation may indicate the need for positive-pressure ventilation. If signs and symptoms suggest inadequate ventilation, measurement of SWC may be helpful in determining respiratory muscle strength and endurance and the potential need for positive-pressure ventilation. Conversely, if no signs and symptoms of inadequate ventilation are present in a patient on positive-pressure ventilation, SWC measurements (in conjunction with other patient data) are useful to determine the patient’s ability to tolerate weaning trials and possibly extubation.

Rationale: Inadequate ventilation may indicate the need for positive-pressure ventilation. If signs and symptoms suggest inadequate ventilation, measurement of SWC may be helpful in determining respiratory muscle strength and endurance and the potential need for positive-pressure ventilation. Conversely, if no signs and symptoms of inadequate ventilation are present in a patient on positive-pressure ventilation, SWC measurements (in conjunction with other patient data) are useful to determine the patient’s ability to tolerate weaning trials and possibly extubation.

• Assess patient’s need for a long-term artificial airway and mechanical ventilatory assistance.  Rationale: Consistently low measurements in conjunction with overall patient status (e.g., mental status, hemodynamics, fluid and electrolyte balance, comfort, mobility) may suggest the need for permanent full-time or part-time ventilator support.

Rationale: Consistently low measurements in conjunction with overall patient status (e.g., mental status, hemodynamics, fluid and electrolyte balance, comfort, mobility) may suggest the need for permanent full-time or part-time ventilator support.

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that the patient understands pre-procedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: This communication evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

Rationale: This communication evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

• Consider positioning the patient in a high semi-Fowler’s position, if the patient’s condition allows.  Rationale: Placing the patient in a high semi-Fowler’s position, if possible, enables the patient to use the force of gravity during measurements.

Rationale: Placing the patient in a high semi-Fowler’s position, if possible, enables the patient to use the force of gravity during measurements.

References

![]() 1. Burns, SM, Burns, JE, Truwit, JD. Comparison of five -clinical weaning indices. Am J Crit Care. 1994; 3:342–352.

1. Burns, SM, Burns, JE, Truwit, JD. Comparison of five -clinical weaning indices. Am J Crit Care. 1994; 3:342–352.

2. Burns, SM, The science of weaning. when and how. Crit Care Clin North Am 2004; 16:379–386.

![]() 3. Chevrolet, J, Deleamont, P. Repeated vital capacity -measurements as predictive parameters of mechanical ventilation need and weaning success in the Guillain-Barre syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991; 144:814–818.

3. Chevrolet, J, Deleamont, P. Repeated vital capacity -measurements as predictive parameters of mechanical ventilation need and weaning success in the Guillain-Barre syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991; 144:814–818.

![]() 4. Cook, D, et al. Evidence report on criteria for weaning from mechanical ventilation. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1999. [contract no. 290-97-0017].

4. Cook, D, et al. Evidence report on criteria for weaning from mechanical ventilation. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1999. [contract no. 290-97-0017].

![]() 5. Ely, EW, et al. Effect on the duration of mechanical -ventilation of identifying patients capable of breathing spontaneously. N Engl J Med. 1996; 335:1964–1969.

5. Ely, EW, et al. Effect on the duration of mechanical -ventilation of identifying patients capable of breathing spontaneously. N Engl J Med. 1996; 335:1964–1969.

![]() 6. Kollef, MH, et al. A randomized controlled trial of protocol directed versus physician directed weaning from mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 1997; 25:567–574.

6. Kollef, MH, et al. A randomized controlled trial of protocol directed versus physician directed weaning from mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 1997; 25:567–574.

![]() 7. Krieger, BP, et al. Serial measurements of the rapid shallow breathing index as a predictor of weaning outcome in elderly medical patients. Chest. 1997; 112:1029–1034.

7. Krieger, BP, et al. Serial measurements of the rapid shallow breathing index as a predictor of weaning outcome in elderly medical patients. Chest. 1997; 112:1029–1034.

![]() 8. MacIntyre, NR, et al, Evidence-based guidelines for -weaning and discontinuing ventilatory support. a collective task force facilitated by the American College of Chest Physicians; the American Association for Respiratory Care; and the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 2001; 120(6 Suppl):375S–395S.

8. MacIntyre, NR, et al, Evidence-based guidelines for -weaning and discontinuing ventilatory support. a collective task force facilitated by the American College of Chest Physicians; the American Association for Respiratory Care; and the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 2001; 120(6 Suppl):375S–395S.

![]() 9. Mador, MJ, Weaning parameters. are they clinically useful. Chest 1992; 102:1642.

9. Mador, MJ, Weaning parameters. are they clinically useful. Chest 1992; 102:1642.

![]() 10. Marelich, GP, et al, Protocol weaning of mechanical ventilation in medical and surgical patients by respiratory care practitioners and nurses. effect on weaning time and incidence of ventilator associated pneumonia. Chest 2000; 118:459–467.

10. Marelich, GP, et al, Protocol weaning of mechanical ventilation in medical and surgical patients by respiratory care practitioners and nurses. effect on weaning time and incidence of ventilator associated pneumonia. Chest 2000; 118:459–467.

![]() 11. Meade, M, Guyett, G, Cook, D, et al. Predicting success in weaning from mechanical ventilation. Chest. 2001; 120(6S):400–424.

11. Meade, M, Guyett, G, Cook, D, et al. Predicting success in weaning from mechanical ventilation. Chest. 2001; 120(6S):400–424.

![]() 12. Yang, KL, Reproducibility of weaning parameters. a need for standardization. Chest 1992; 102:1829–1832.

12. Yang, KL, Reproducibility of weaning parameters. a need for standardization. Chest 1992; 102:1829–1832.

![]() 13. Yang, KL, Tobin, MJ. A prospective study of indexes predicting the outcome of trials of weaning from mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 1991; 324:1445–1450.

13. Yang, KL, Tobin, MJ. A prospective study of indexes predicting the outcome of trials of weaning from mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 1991; 324:1445–1450.

Burns, SM. Mechanical ventilation and weaning. In: Carlson KK, ed. AACN advanced critical care nursing. St Louis: Elsevier, 2009.

Burns, SM. Weaning from mechanical ventilation. In Burns SM, ed. : AACN protocols for practice: care of -mechanically ventilated patients, ed 2, Boston: Jones and Bartlett, 2007.

Mahanes, D, Lewis, R, Ventilatory management. AACN-AANN protocols for practice: monitoring technologies in -critically ill neuroscience patients, Publishers. Jones and Bartlett, Boston, 2009.