CHAPTER 35. Gastrointestinal Care

Denise O’brien

OBJECTIVES

At the conclusion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. List name and locate the major anatomical components of the gastrointestinal tract and the accessory organs of digestion.

2. Identify the major functions of each of the divisions of the gastrointestinal system and the accessory organs of digestion.

3. Describe the fluid and electrolyte problems most frequently encountered in the patient with a gastrointestinal disorder.

4. Incorporate the care of the other body systems into the postoperative management of the gastrointestinal surgery patient.

5. Describe two specific system complications of the gastrointestinal surgery patient.

6. State the rationale for placement of tubes and drains in the gastrointestinal surgery patient.

7. State the rationale for observations necessary in postanesthesia care of the patient undergoing gastrointestinal surgery.

Acknowledgement: I thank Lisa Colletti, MD, for her assistance in preparing this chapter.

I. ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

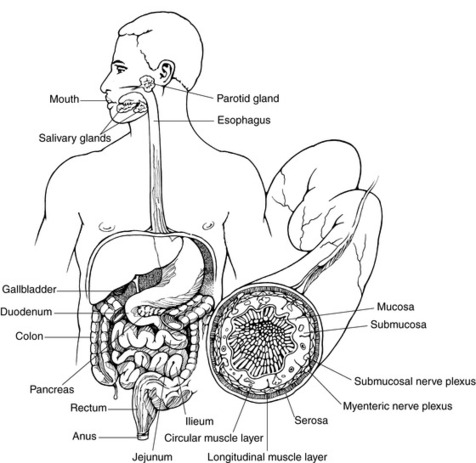

A. Major anatomic components (Figure 35-1)

1. Mouth

a. Begins mechanical breakdown of food

b. Secretion of saliva

c. Tongue

d. Teeth

2. Pharynx

3. Esophagus

a. Carries food to stomach through peristalsis

b. Lower esophageal sphincter

4. Stomach

a. Main site of digestion

b. Produces digestive enzymes

c. Cardiac sphincter

(1) Prevents backflow of food and digestive enzymes

d. Fundus

(1) Begins digestion of proteins

e. Pylorus

(1) Contracts to empty stomach contents into small intestine

f. Pyloric sphincter

(1) Prevents food and digestive enzymes from entering the small intestine before digestion is completed

g. Rugae

(1) Provide the stomach with increased surface area

(2) Expands with food

5. Small intestine

a. Duodenum

(1) Chemical digestion occurs

(a) Neutralizes stomach acids

(b) Breaks down carbohydrates and fats

b. Jejunum

(1) Absorbs most nutrients

c. Ileum

(1) Absorbs water and vitamins

d. Villi

6. Large intestine

a. Absorbs remaining water and vitamins

b. Appendix

c. Colon

d. Rectum

e. Anus

|

| FIGURE 35-1 ▪

The gastrointestinal system.

(From Ignatavicius DD, Bayne MV: Medical-surgical nursing, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders.)

|

B. Accessory organs of digestion

1. Salivary glands

a. Produce amylase

b. Begins chemical breakdown of starch

c. Provides lubrication

2. Liver

a. Detoxifies

b. Neutralizes stomach acid

c. Produces bile

3. Gallbladder

a. Stores bile

4. Pancreas

a. Produces insulin

b. Produces digestive enzymes that are released into the duodenum

II. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

A. Neoplasms and growths

1. Malignancies

a. Primary

b. Metastatic

2. Polyps: a benign proliferation of cells lining the gastrointestinal tract

a. Some with potential for malignant transformation

3. See Strictures (II.C.1) and Adhesions below (II.C.2).

B. Calculi

1. Calculi or stones (e.g., cholelithiasis), primarily resulting from supersaturation of bile with cholesterol

C. Strictures or obstructions

1. Stricture: abnormal narrowing of gastrointestinal passage

a. Neoplasms commonly cause strictures; for example:

(1) Colon

(2) Biliary tree

b. Strictures can:

(1) Progress to obstruction (blockage of gastrointestinal passage)

(2) Be caused by adhesions

2. Adhesions: union of two normally separate surfaces or a fibrous band that connects them

a. Occasionally, produce obstruction or malfunction of an organ

b. Result of the formation of scar tissue

c. Abdominal surgery results in the formation of:

(1) Adhesions

(2) Scar tissue

(3) Magnitude of these adhesions or scar tissue varies.

d. Approximately 5% of cases associated with adhesions occur in persons who have had no previous abdominal surgery.

(1) Virtually always the result of some other previous or ongoing pathological process, such as:

(a) Pelvic inflammatory disease

(b) Appendicitis

(c) Diverticulitis

D. Ulceration

1. Ulcer disease

a. Peptic ulcer disease

(1) Helicobacter pylori ( H. pylori)

(2) Medications

(a) Aspirin

(b) Steroids

(c) Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents

b. Stress ulceration, resulting from the following:

(1) Surgical stress

(2) Burns

(3) Cranial trauma

(4) Sepsis associated with multisystem failure

E. Perforations

1. Caused by ulceration

2. Resulting from trauma

3. Can also result from vascular compromise or obstruction

F. Inflammation

1. Regional enteritis (Crohn’s disease)

2. Cholecystitis

3. Pancreatitis

4. Appendicitis

5. Diverticulitis

6. Esophagitis

7. Gastritis

8. Ulcerative colitis

G. Altered innervation

1. Achalasia

H. Congenital defects

1. Hirschsprung’s disease

2. Tracheoesophageal fistula

3. Imperforate anus

4. Pyloric stenosis

5. Arteriovenous malformation

I. Ischemia: arterial or venous infarction

1. Complication after abdominal aortic aneurysmectomy

2. After repair of coarctation of aorta

3. After coronary artery bypass

4. Embolic

5. Related to atherosclerosis of the abdominal vasculature; can result in mesenteric ischemia

6. Low flow states: either related to cardiac disease, especially congestive heart failure, or sepsis

J. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

1. Results from the reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus

2. Symptoms may include:

a. Heartburn

b. Gastric regurgitation

c. Dysphagia

d. Pulmonary manifestations

(1) Asthma

(2) Coughing

(3) Wheezing

(4) Laryngeal inflammation

III. DIAGNOSTIC TESTS OR PROCEDURES

A. Tests ordered depend on gastrointestinal area thought to be involved.

B. Laboratory tests

1. Basic hematology and electrolyte studies

2. Serum enzyme levels

a. Amylase

b. Lipase

c. Liver function tests or hepatic function panel

(1) Albumin

(2) Bilirubin (total and direct)

(3) Aspartate aminotransferase (AST)

(4) Alanine aminotransferase (ALT)

(5) Alkaline phosphatase

(6) Total protein

3. Serum markers

a. CA 19-9 for pancreatic cancer

b. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) for hepatocellular cancer

c. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) for different types of cancer

(1) Pancreas

(2) Large intestine (colon and rectum)

(3) Breast

(4) Lung

4. Coagulation studies

a. If liver involvement suspected

b. With malabsorption syndromes

(1) Cause malabsorption of vitamins that can compromise metabolism of coagulation factors produced by liver

C. Endoscopic procedures

1. Motility studies (e.g., esophageal manometry)

2. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD)

3. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

a. With or without stents

b. With or without sphincterotomy

c. Purpose

(1) To remove retained common duct stones before or after biliary tract surgery

(2) As an emergency measure in patients with common bile duct obstruction (single or multiple stones) resulting in cholangitis

(3) May be done preoperatively to explore common bile duct in patients needing:

(a) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy

(b) Temporary or permanent treatment for biliary obstruction and jaundice

(i) Pancreatic malignancies

(ii) Biliary malignancies

d. Description—by use of side-viewing fiberoptic endoscope:

(1) Pancreatic and biliary ducts cannulated through ampulla of Vater

(2) Ducts visualized fluoroscopically after retrograde injection of radiopaque contrast medium

4. Colonoscopy

5. Sigmoidoscopy

6. Twenty-four-hour pH monitoring with probe for reflux

D. Radiological examinations

1. Barium swallow

2. Upper gastrointestinal series—may also include a small bowel follow-through to evaluate:

a. Small intestine

b. Stomach

c. Duodenum

3. Cholangiogram—typically done as part of:

a. ERCP

b. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC)

c. Operatively

4. PTC

5. Barium enema

6. Flat plate of abdomen

7. Visceral angiography

a. Angiography

b. Carbon dioxide (CO 2) digital subtraction angiography

8. Computed tomography (CT) scan

E. Other modalities

1. Endoscopic ultrasonography

a. Endoscopic ultrasonography of:

(1) Esophagus

(2) Stomach

(3) Pancreas

(4) Biliary tree

b. Transanal ultrasonography

2. Radionuclide

a. Gastrointestinal studies

b. Liver and spleen studies

c. Hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan for acute cholecystitis or to detect biliary leak

d. Labeled red blood cells to check site of bleeding

3. Magnetic resonance imaging

4. Magnetic resonance angiography: used to evaluate vasculature

5. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

F. Tissue biopsies as indicated with cytological or histological studies; typically done with ultrasound or CT guidance

IV. INTRAOPERATIVE CONCERNS

A. Proper positioning

1. Maintain neurovascular integrity.

a. Padding and support of all body parts with particular attention given to vulnerable areas (e.g., elbows, sacrum, heels, occiput)

b. For comfort

c. Proper alignment in presence of arthritis, lumbar disorders, and contractures

d. Preserve integrity of popliteal nerve and/or ulnar and brachial nerve plexus when lithotomy or exaggerated arm abduction is used.

2. Prevent complications.

a. Proper application of electrosurgical grounding pads to prevent cautery burns; avoid contact with metal or hard surfaces.

b. Careful positioning changes of anesthetized patient (to and from Trendelenburg or lithotomy position) to prevent adverse alterations in tidal volume and cardiac output; position of padding and support rechecked after each change

c. Protect skin from shearing while positioning and moving.

B. Cardiovascular stability

1. Factors influencing altered fluid volume, electrolyte, and nutritional status

a. Chronic bleeding

b. Diarrhea

c. Vomiting

d. Increased secretions

e. Fluid loss

(1) Nasogastric suctioning

(2) Fistula drainage

(3) Bowel preparation

(4) Length of operative procedure

2. Problems with preceding factors if not corrected preoperatively

a. Hypotension: caused by deficits in circulating volume

(1) Poorly tolerated in pediatric, elderly, and debilitated patients vulnerable to adverse effects of hypotension because of decreased body reserve necessary to handle crises

(2) Potential rapid fluid (blood) loss because of rich intestinal blood supply and its proximity to aorta and vena cava

(3) Rapid fluid resuscitation with crystalloid or colloid solution can result in overhydration, leading to pulmonary edema and congestive heart failure in compromised patient.

b. Altered electrolyte balance: cardiac dysrhythmias can occur with abnormal potassium or calcium levels.

c. Clotting abnormalities caused by poor nutritional status or hemodilution or in presence of liver disease

(1) Decreased vitamin K, leading to decreased levels of factors V, VII, IX, and X

(2) Prolonged prothrombin times

C. Thermal regulation (see Chapter 24)

1. Hyperthermia

a. Elevated temperature on arrival in the operating room, possibly as a result of:

(1) Infection

(2) Peritonitis

(3) Other inflammatory process

b. Anesthesia care provider must observe for signs and symptoms of possible adverse reaction to anesthetic agents and muscle relaxants, which may lead to malignant hyperthermia, either in operating room or in post anesthesia care unit (PACU).

2. Hypothermia

a. Prolonged exposure of abdominal viscera causes loss of body heat.

(1) Procedures of 3 or more hours

(2) Extensive gastrointestinal resection

b. Large-volume fluid or blood/blood product resuscitation without adequately warming fluids

c. Temperature control methods

(1) Room temperature control

(2) Use of warming mattresses, convective warming devices, and protective coverings

(3) Warming of intravenous (IV) and irrigating fluids

D. Drug interactions and other concerns

1. Nondepolarizing muscle relaxants (see Chapter 22)

a. Antagonized by hypothermia

b. Patients may reparalyze with postoperative warming.

c. May have slowed return of neuromuscular function because of:

(1) Hypothermia

(2) Decreased elimination of some relaxants (those eliminated by Hofmann elimination)

d. Potentiated by broad-spectrum antibiotics (mycins, aminoglycosides)

2. Metabolism and excretion of medications impaired in presence of:

a. Liver dysfunction

b. Renal failure

c. Obesity

3. Avoid use of histamine-releasing agents such as morphine sulfate.

a. Histamine release can cause hypotension in hypovolemic patient.

4. All opioids increase biliary tract pressure, which may cause spasm of sphincter of Oddi, producing severe right upper quadrant or substernal pain in the patient with biliary obstruction or disease.

a. Severity of symptoms (pain, nausea, diaphoresis, hypotension) requires that myocardial infarction be ruled out.

b. Symptoms usually abate with administration of naloxone (Narcan) or glucagon.

5. Rapid sequence induction (“crash” induction): possible indications

a. History of gastroesophageal reflux

b. Stricture of gastroesophageal sphincter

c. History of recent eating before emergency surgery

d. Bowel obstruction

e. History of gastroparesis

6. Spillage of feces or bile into peritoneal cavity is potential cause of chemical or bacterial peritonitis and should be documented.

V. GASTROINTESTINAL OPERATIVE PROCEDURES

A. Esophageal procedures

1. Cervical esophagostomy

a. Purpose—often done as part of first-stage repair in infants for:

(1) Tracheoesophageal fistula

(2) Esophageal atresia

b. Description: surgical formation of opening into esophagus at cervical level

c. Preoperative phase I assessment and concerns

(1) At risk for aspiration; gastrostomy tube placed as soon as atresia or fistula identified

(2) May have multiple anomalies of cardiovascular, gastrointestinal systems

d. Postanesthesia phase I priorities

(1) Maintain normothermia.

(2) Tracheal leak may be present.

(3) Pain management

e. Complications

(1) Pulmonary aspiration

(2) Vocal cord paralysis

2. Esophagectomy with colon or gastric interposition

a. Purpose: used in presence of esophageal atresia or for esophageal damage anywhere, except very proximal cervical esophagus

(1) Commonly performed for:

(a) Esophageal malignancies

(b) End-stage achalasia

b. Description: usually a piece of colon or stomach (more common) is used to establish continuity between esophagus and stomach.

c. Preoperative assessment and concerns

(1) May have recurrent aspiration pneumonia from gastric reflux

(2) Malnutrition related to dysphagia or anorexia

(3) Evaluation of cardiovascular and respiratory status (may be compromised in patients with esophageal malignancies because these patients often are smokers and drink excess alcoholic beverages)

d. Intraoperative concerns

(1) Hypothermia

(2) Positioning to avoid neural injuries or soft tissue damage

e. Postanesthesia phase I priorities

(1) At risk for aspiration and atelectasis; head of bed elevated

(2) Pain management: consider thoracic epidural continuous analgesia.

(3) Assess for hypoventilation, pneumothorax, anastomotic leak.

(4) Patient may be hoarse.

f. Complications

(1) Aspiration

(2) Atelectasis, hypoventilation

(3) Hemorrhage

(4) Pneumothorax

(5) Esophageal anastomotic leak

(6) Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury

3. Esophageal dilation

a. Purpose: to allow free passage of food and fluids into stomach; used to correct:

(1) Achalasia

(2) Esophageal spasms

(3) Strictures

b. Description: dilating instruments (bougies or balloons) passed in increasingly larger sizes or inflated to enlarge lumen of esophagus

c. Preoperative assessment and concerns

(1) Nothing by mouth (NPO) before procedure

d. Intraoperative concerns

(1) Procedure may be done with sedation and analgesia or with general anesthesia.

e. Postanesthesia priorities

(1) Phase I

(a) Minimal postprocedure pain expected

(b) Observe for:

(i) Subcutaneous emphysema

(ii) Pain

(iii) Aspiration

(c) Monitor temperature.

(2) Phase II

(a) Assess gag reflex before giving fluids.

(b) Review appropriate instructions with patient, family, and responsible accompanying adult.

f. Psychosocial concerns

(1) May require frequent dilations

(2) May prefer particular type of sedation or anesthesia for procedure based on past experience

g. Complications

(1) Esophageal perforation

(2) Pain

(3) Hemorrhage

(4) Bacteremia or sepsis

4. Esophagomyotomy (Heller procedure)

a. Purpose: to allow food to pass from esophagus to stomach when a segment of esophagus is narrowed, causing functional obstruction

b. Description: surgical division or anatomical dissection of muscles at distal esophagogastric junction, leaving mucosa intact

5. Herniations (see Chapter 36)

a. Part of stomach protruding through an opening, or hiatus, in diaphragm

b. Surgical repair of hiatal or diaphragmatic hernias accomplished through either an abdominal or a thoracic approach

c. Hiatal hernia is not a true hernia, while diaphragmatic hernia is.

(1) Hiatal hernia occurs when the gastroesophageal junction slides up and down between the chest and abdomen.

(2) Tends to be associated with GERD

(3) No indication to fix hiatal hernia unless patient also has GERD

d. Diaphragmatic hernia is a true hernia and should always be repaired because of risk of incarceration or strangulation of the stomach.

e. Purposes

(1) To restore herniated part below diaphragm for diaphragmatic hernias

(2) For patients with GERD and hiatal hernias

(a) To narrow esophageal hiatus

(b) To recreate esophagogastric angle to enhance lower esophageal sphincter function

(c) To stop reflux of gastric contents

f. Description (these procedures are done for GERD and not specifically for a hiatal hernia)

(1) Collis-Belsey and Collis-Nissen repairs: esophageal lengthening with antireflux wrap of distal esophagus

(2) Hill repair: abdominal approach that narrows esophageal orifice and fixes esophagogastric junction in intra-abdominal position; includes 180 ° wrap of stomach around esophagus

(3) Belsey Mark IV repair: performed through incision in left side of chest

(a) Consists of 240 ° wrap of distal portion of esophagus with fundus of stomach

(b) This partial fundoplication is technically difficult.

(c) Risk of leakage or diverticulum developing in esophagus is higher because sutures are required in esophageal wall.

(d) Newer procedure: modified thoracoscopic Belsey repair

(4) Nissen fundoplication: transabdominal or laparoscopic (similar to open approach and most common procedure for this condition) treatment for sliding esophageal hiatal hernia

(a) Portion of fundus of stomach is mobilized and completely wrapped around (360 °) distal portion of esophagus.

(b) Prevents stomach displacement into posterior portion of mediastinum through diaphragmatic defect

(5) Toupet partial fundoplication: alternative antireflux procedure; fundal wrap reduced to 180 ° to 270 °

g. Preoperative assessment and concerns

(1) Possible recurrent aspiration pneumonia

(2) Antacid and antireflux prophylaxis recommended

h. Intraoperative concerns

(1) Aspiration risk during induction and emergence

(2) Hemorrhage

(3) Visceral injury

(4) Hypothermia

i. Postanesthesia priorities

(1) Phase I

(a) Nausea and vomiting

(b) Shoulder pain (if laparoscopic approach)

(c) Pain management

(d) Hypoventilation

(2) Length of stay usually 2 to 3 days for Nissen fundoplications

j. Complications

(1) Gastric perforation

(2) Bleeding, hemorrhage

(3) Pneumothorax

(4) Aspiration

(5) Hypoventilation

(6) Wrap too tight, with resultant dysphagia and difficulty eating/swallowing

6. Esophageal band ligation

a. Purpose: to obliterate esophageal varices to reduce risk of bleeding or hemorrhage

b. Description: endoscopic procedure involves placing a band around (ligation) varices in esophagus.

c. Preoperative assessment and concerns

(1) NPO before procedure

d. Intraoperative concerns

(1) Procedure may be done with sedation and analgesia or with general anesthesia.

e. Postanesthesia priorities

(1) Phase I

(a) Minimal postprocedure pain expected

(b) Observe for:

(i) Subcutaneous emphysema

(ii) Severe pain

(iii) Aspiration

(c) Monitor temperature.

(d) Watch for bleeding.

(2) Phase II

(a) Assess gag reflex before giving fluids.

(b) Review appropriate instructions for postsedation or postanesthesia care with patient, family, and responsible accompanying adult.

(c) Verify that patient and caregiver are aware of potential for bleeding and when to notify surgeon.

f. Psychosocial concerns

(1) Patient may require repeat procedures.

(2) Patient may prefer particular type of sedation or anesthesia for procedure based on past experience.

g. Complications

(1) Esophageal perforation

(2) Aspiration pneumonitis

(3) Hemorrhage

(4) Bacteremia and sepsis

B. Gastric procedures

1. Gastrectomy

a. Purpose: to remove all or a portion of diseased organ; most commonly performed for cancer

b. Description: surgical removal of whole or a part of stomach

(1) Antrectomy

(a) Involves almost a 50% distal gastrectomy

(b) Antral mucosa (site of gastrin formation) removed, usually in conjunction with truncal vagotomy

(c) Remaining portion of stomach anastomosed to duodenum or jejunum

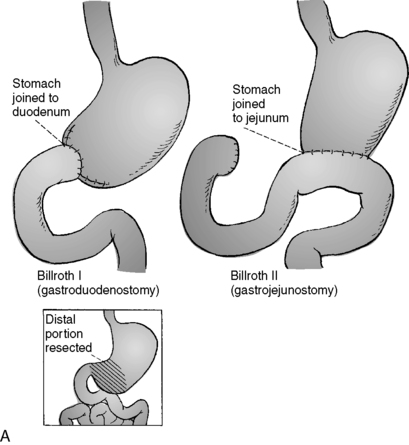

(2) Billroth I (gastroduodenostomy): type of reconstruction used with an antrectomy

(a) First portion of duodenum sewn to remaining portion of stomach (Figure 35-2)

|

|

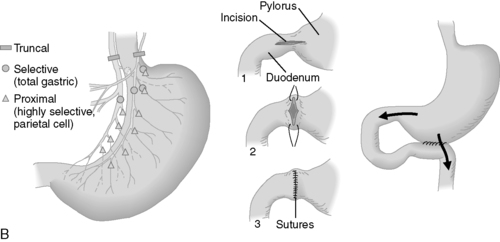

| FIGURE 35-2 ▪

Gastric surgical procedures. A, Billroth I, Billroth II. B, Vagotomy (left); pyloroplasty (middle); gastroenterostomy (right).

(From Black JM, Hawks JH: Medical-surgical nursing: Clinical management for positive outcomes, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2005, Saunders.)

|

(3) Billroth II (gastrojejunostomy): reconstruction used with an antrectomy

(a) First portion of duodenum is unable to reach remaining portion of stomach.

(b) First portion of the duodenum is sewn shut.

(c) Loop of jejunum just distal to ligament of Treitz is brought up and sewn to remaining stomach remnant (Figure 35-2).

(4) Total gastrectomy: done for cancer of stomach or abdominal esophagus; reconstruction after total gastrectomy usually by esophagojejunostomy

(5) Near total gastrectomy: may be done for treatment of gastroparesis

(6) Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy: reconstruction procedure for the stomach

(a) May be used for reconstruction after antrectomy or after total gastrectomy

(b) Used as a bypass procedure for unresectable pancreatic cancer

(c) More commonly a loop gastrojejunostomy used in this situation (a loop of jejunum is sewn to stomach to bypass an obstructed distal stomach or duodenum)

c. Preoperative assessment and concerns

(1) Rehydration

(2) Possible transfusion because of bleeding

(3) Possible hyperalimentation for nutritional deficits

(4) Electrolyte abnormalities

d. Intraoperative concerns

(1) Volume status

(2) Anticipate significant third space losses.

(3) Acute hemorrhage

e. Postanesthesia phase I priorities

(1) Low thoracic epidural for pain management; patient-controlled analgesia also an option

(2) Maintain nasogastric tube patency and position.

2. Gastric bypass (see Chapter 48)

3. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (see Chapter 48)

4. Gastroenterostomy (Figure 35-2)

a. Purpose: to create an artificial passage between stomach and small intestine

b. Description: surgical anastomosis between stomach and small intestine, usually jejunum, for unresectable pancreatic cancer with gastric outlet obstruction

5. Gastrostomy

a. Purpose: used for long-term stomach decompression or to introduce food into gastrointestinal system

b. Description: creation of gastric fistula or opening through abdominal wall, usually with a tube in place

(1) May be done operatively or endoscopically (insertion of gastrostomy tube through incision made at point where anterior portion of stomach wall is tented with endoscope, making contact with parietal peritoneum)

(2) Traction on tube maintains contact between stomach and abdominal wall.

c. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG)

(1) Endoscopic procedure performed with local anesthesia

(2) Relative and/or absolute contraindications to PEG

(a) Prior gastric surgery

(b) Portal hypertension with varices and/or ascites

(c) Ascites from other causes

(d) Prior abdominal surgery

6. Pyloromyotomy

a. Purpose: to widen pyloric opening

b. Description: muscle fibers of outlet of stomach are cut without severing mucosa.

7. Pyloroplasty (see Figure 35-2)

a. Purpose: to increase size of pyloric opening in presence of pyloric stenosis or scarring caused by ulcer disease; usually performed in conjunction with vagotomy when done for latter

b. Description: repair of pylorus used to establish opening in presence of pyloric or prepyloric obstruction

8. Vagotomy (see Figure 35-2): since recognition of H. pylori, almost never done anymore

a. Purpose: to reduce amount of gastric acid secreted and lessen chance of recurrence of peptic ulcer

b. Description: sectioning of vagus nerve or its branches; choices of vagotomy include:

(1) Truncal

(2) Selective

(3) Proximal (highly selective, parietal cell)

(4) May be accomplished by laparoscopic approach

c. Needs to be performed in conjunction with an “emptying procedure,” either pyloroplasty or partial gastrectomy (antrectomy)

C. Biliary, hepatic, and pancreatic procedures

1. Surgical correction of biliary atresia (condition in which extrahepatic bile ducts are nonpatent, seen primarily in infants) or any type of biliary obstruction in adults

a. Stones

b. Strictures

c. Surgical injury (lap chole injury)

d. Distal biliary obstruction due to chronic pancreatitis

e. Sclerosing cholangitis

f. Biliary carcinoma

2. Roux-en-Y procedure

a. Purpose—used when:

(1) Proximal extrahepatic bile ducts patent

(2) Distal ducts occluded

(3) For bypass in cancer of bile duct and pancreatitis

b. Description: distal end of divided jejunum anastomosed to patent remnant of proximal bile duct

3. Hepatic portoenterostomy (Kasai procedure): typically done in infants/children for biliary atresia

a. Purpose: used when proximal extrahepatic ducts are totally occluded

b. Description: removal of entire extrahepatic biliary tree; bile drainage established by anastomosis of intestinal conduit to transected ducts at liver hilus

c. Preoperative assessment and concerns

(1) May have impaired elimination of drugs because of hepatic dysfunction

(2) Coagulation values need to be evaluated.

d. Intraoperative concerns

(1) Potential for large third-space losses

e. Postanesthesia/phase I priorities

(1) Monitor volume status.

f. Complications: cholangitis

4. Cholecystectomy (see Chapter 36)

a. Purpose: to treat cholelithiasis and cholecystitis

b. Description: removal of gallbladder and its cystic duct

(1) May be through traditional “open” approach or by laparoscopy

(2) Laparoscopic approach may use the following to remove the gallbladder from liver bed and ligate vessels and ducts:

(a) Laser

(b) Electrosurgical cautery

(c) Harmonic scalpel

c. Intraoperative concerns

(1) High incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting; prophylactic antiemetics recommended before end of case

(2) Pneumoperitoneum if laparoscopic; risk of gas embolism

d. Postanesthesia priorities

(1) Phase I

(a) Postoperative nausea and vomiting management

(b) Shoulder pain (both open and laparoscopic approaches)

(2) Phase II

(a) Minimal nausea and vomiting for discharge home

(b) Oral analgesics initiated as needed for pain management before discharge

(c) Instruct patient and companion regarding:

(i) Diet

(ii) Incision sites

(iii) Care of incisions

5. Cholecystostomy

a. Purpose: to decompress gallbladder of debilitated patient with acute cholecystitis or cholelithiasis unable to tolerate cholecystectomy at that time

b. Description: formation of opening into gallbladder through abdominal wall

(1) If stones present, approach may be by angiography with lithotripsy to break up stones.

(2) Usually done with local anesthesia and sedation

c. Preoperative assessment and concerns

(1) Dehydration from the following may require fluid resuscitation before operative procedure:

(a) Fever

(b) Vomiting

(c) Decreased oral intake

(2) Peritonitis

(3) Sepsis

6. Choledochotomy

a. Purpose: usually for removal of stones

b. Description: incision of common bile duct

c. Preoperative assessment and concerns

(1) As in preceding section (V.C.5.c)

7. Common bile duct exploration

a. Purpose

(1) To check for stones and/or strictures

(2) Frequently performed at time of cholecystectomy

b. Description: exploration of common bile duct

(1) T-tube drain left in place for a period of time postoperatively to ensure patency of common bile duct

(2) Can use laparoscopic approach

8. Hepaticojejunostomy

a. Purpose

(1) To repair stricture of common bile duct after laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy

(2) May also be done for patients with bile duct cancer

b. Description: creation of anastomosis between hepatic duct and jejunum

9. Portal systemic shunt: rarely done now; transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure more commonly done in radiology

a. Purpose—primarily used for treatment of:

(1) Portal hypertension

(2) Decompression of esophagogastric varices

b. Increasing use of TIPS procedures reduces the number of older shunt procedures.

c. Since liver transplantation more commonly performed, these patients also treated with hepatic transplantation, rather than shunting

(1) TIPS commonly used as a bridge to transplantation

d. Description: shunts divert, either partially or totally, portal venous blood flow to liver

(1) Types of shunts include:

(a) End-to-side

(b) Side-to-side

(c) Interposition

(d) Sarfeh portacaval

(e) Interposition (adult) or direct (pediatric) mesocaval

(f) Distal splenorenal

(g) Mesoatrial (Budd-Chiari syndrome management)

(2) Sugiura procedures (combines esophageal transection, extensive esophagogastric devascularization, and splenectomy, while paraesophageal collateral vessels are preserved)

(a) Done for varices in patients who are not candidates for shunt procedures

(b) Procedure not a shunt procedure

10. TIPS

a. Purpose: definitive treatment for patients who bleed from portal hypertension

(1) Major limitation is that up to 50% have shunt stenosis or shunt thrombosis within the first year.

(2) May be ideal therapy for patients needing short-term portal decompression (those awaiting liver transplantation who fail sclerotherapy)

b. Description

(1) Nonoperative

(a) Functions similarly to a side-to-side portosystemic shunt (effective in treating ascites)

(b) Adverse side effects include:

(i) Total portal diversion

(ii) Encephalopathy

c. Procedure

(1) Needle advanced from a hepatic vein to a major portal branch

(2) Guide wire placed

(3) Hepatic parenchymal tract created by balloon dilation

(4) Expandable metal stent placed, creating shunt

d. Preoperative assessment and concerns

(1) Hypoxemia secondary to ascites

(2) Portal hypertension

(3) Risk for bleeding from esophageal and gastric varices

(4) Risk of bleeding from coagulopathy due to liver dysfunction

(5) Renal failure

(6) Anemia

(7) Altered drug elimination

(8) Electrolyte disturbances

e. Intraoperative concerns

(1) Anticipate large blood loss for open procedures.

(2) Pulmonary artery catheter for monitoring

f. Postanesthesia/phase I priorities

(1) Intensive care monitoring usual following these procedures

g. Complications

(1) Coagulopathy

(2) Encephalopathy

(3) Renal failure

11. Hepatectomy: excision of all or part of liver

a. Increasing use of segmentectomies and wedge resections for patients with liver metastases

b. Cryotherapy or radiofrequency ablation also used to treat:

(1) Primary liver cancer

(2) Hepatic metastases

12. Hepatic lobectomy: surgical removal of one of the two (right, left) lobes of liver; each lobe is then divided into several segments (eight total)—if a segment is removed, segmentectomy; may be accomplished with total vascular occlusion intraoperatively

a. Intraoperative concerns (for hepatectomy and hepatic lobectomy)

(1) Potential for large blood loss

b. Postanesthesia phase I priorities

(1) Epidural analgesia for pain management

(2) May remain intubated and ventilated

(3) Anticipate intensive care monitoring

c. Complications

(1) Massive hemorrhage

(2) Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy

(3) Hypoglycemia

(4) Electrolyte imbalance

(5) Pulmonary insufficiency

(6) Encephalopathy

(7) Liver failure

(8) Renal failure

13. Peritoneovenous shunts (e.g., LeVeen or Denver); not commonly used

a. Purpose

(1) Used in an attempt to control ascites by reinfusing peritoneal fluid into venous system

(2) Patients with limited hepatic reserve who may not tolerate blood being shunted away from liver are candidates.

(3) Used to palliate patients with malignant ascites

b. Description

(1) Unidirectional silicone elastomer valve and catheter inserted into peritoneum

(2) Other end tunneled subcutaneously up to neck and inserted into internal jugular vein

(3) Catheter then threaded into superior vena cava or right atrium

c. These shunts have significant problems with occlusion.

(1) Particularly in patients with malignant ascites

(2) Due to high cell and protein levels

(3) Shunts need to be frequently pumped to maintain patency.

14. Liver transplant

a. Purpose

(1) Replacement of diseased liver with donor liver

(2) May use cadaveric or living-related (split-liver) organs

b. Description

(1) Native liver removed and replaced with whole liver (cadaveric) or liver segment (split liver or liver segment from a living donor)

(2) Effective approach for treatment of liver failure of various causes because of:

(a) Development of improved surgical techniques

(b) Venous bypass method

(c) Newer antirejection agents

c. Preoperative assessment and concerns

(1) Fifteen percent of all liver transplant recipients in the United States are children.

(2) Premedications used with care

(3) Avoid intramuscular injections.

d. Intraoperative concerns

(1) Monitoring includes:

(a) Arterial line

(b) Central venous pressure

(c) Pulmonary artery catheter

(d) Transesophageal echocardiogram

(2) Warming essential

(3) Massive blood loss and subsequent transfusion

(4) Volume management

e. Postanesthesia phase I priorities

(1) May remain intubated and mechanically ventilated; extubation may occur in operating room or immediately postoperatively in hemodynamically stable patients.

(2) Monitored in intensive care setting or specialized transplant unit

(3) Pain can be severe.

f. Psychosocial concerns

(1) Psychological preparation essential

(2) Provide family support.

g. Complications

(1) Bleeding

(2) Neurological deficits

(3) Hepatic artery and/or portal vein thrombosis

(4) Bile leaks

(5) Rejection: primary or delayed

(6) Renal failure

(7) Electrolyte abnormalities

(8) Pulmonary complications

(9) Liver failure

15. Pancreatectomy

a. Purpose—to treat:

(1) Cancer

(2) Necrosis

(3) Abscess

(4) Pseudocysts

(5) Intractable pain from injury or pancreatitis

(6) Most commonly used to treat pancreatic cancer

b. Description

(1) Partial resection or total removal of pancreas

(2) Total removal results in diabetes and other metabolic difficulties.

(3) May use jejunal loop to drain

16. Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple’s procedure)

a. Purpose

(1) Treat cancer of head of pancreas.

(2) For resectable localized cancers of:

(a) Ampulla

(b) Distal common bile duct

(c) Duodenum

(d) Also used to treat chronic pancreatitis

b. Description—removal of:

(1) Proximal portion of pancreas adjoining duodenum

(2) Lower portion of stomach, gallbladder, and common bile duct

17. Distal pancreatectomy

a. Used to treat:

(1) Malignancies

(2) Benign (but symptomatic) neoplastic cysts

(3) Pancreatic pseudocysts

(4) Distal pancreatitis

(5) Combined with splenectomy, especially if done for malignancy, in order to resect lymph nodes and spleen for staging purposes

18. Cystogastrostomy, cystoduodenostomy, cystojejunostomy

a. Purpose: to treat pancreatic pseudocysts that do not disappear spontaneously

b. Description: decompressive procedures for internally draining pseudocysts that are fixed to retrogastric area or duodenum or not in proximity to either stomach or duodenum

c. Preoperative assessment and concerns (for pancreatectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, and cystogastrostomy)

(1) Jaundice and abdominal pain may be present.

(2) Electrolyte abnormalities

(3) Blood glucose monitoring

d. Intraoperative concerns

(1) Anticipate large fluid loss.

(2) Invasive monitoring usually required

e. Postanesthesia phase I priorities

(1) Epidural analgesia for pain management

(2) Glucose monitoring; prone to hyperglycemia

(3) For patients with chronic pancreatitis, pain management can often be difficult because of long-term use of opioids for chronic pain associated with chronic pancreatitis.

f. Complications

(1) Hypovolemia

(2) Hyperglycemia

(3) Hypocalcemia

19. Pancreas transplant

a. Purpose: to treat diabetes mellitus; establishes an insulin-independent euglycemic state

b. Description

(1) Donor pancreatic tissue transplanted into recipient

(2) Achieved through various techniques

(a) Whole organ

(b) Segmental graft

(c) Duct management occluded or drained into a hollow viscus; usually combined with a renal transplant procedure

c. Preoperative assessment and concerns

(1) Absence of infection, dental evaluation completed

(2) Blood glucose assessment and monitoring

(3) If on dialysis, may need dialysis before procedure

d. Intraoperative concerns

(1) Increased risk for aspiration

(2) Blood glucose monitoring

e. Postanesthesia phase I priorities

(1) Pain management: use caution with opioids if renal failure or nonfunctioning renal transplant.

(2) Blood glucose monitoring: early return to euglycemic state possible after surgery

f. Complications

(1) Rejection

(2) Graft thrombosis

20. Splenectomy or splenorrhaphy

a. Purpose: treat

(1) Traumatic injuries to spleen

(2) Thrombocytopenic purpura refractory to other treatment

(3) Anemias

(4) Myeloproliferative disorders (e.g., leukemia)

(5) Splenorrhaphy only used for traumatic injuries; all other listed disorders (including trauma) treated with total splenectomy

b. Description

(1) Excision or repair of spleen, either by open or laparoscopic approach

(2) Laparoscopic approach generally not used for trauma

D. Small intestine

1. Duodenojejunostomy

a. Purpose: relieve duodenal obstruction

b. Description: creation of opening or passage from obstructed or stenosed duodenum into jejunum

2. Feeding jejunostomy

a. Purpose: allow access for alimentation in presence of functioning gastrointestinal tract.

b. Description: permanent opening or fistula into jejunum through abdominal wall, usually with placement of a tube

3. Ileostomy

a. Purpose—created after total proctocolectomy for:

(1) Crohn’s disease

(2) Ulcerative colitis

(3) Less frequently for:

(a) Multiple colorectal carcinomas

(b) Familial polyposis coli

(c) Ischemia

(d) Trauma

(e) Congenital anomalies in which colon remains intact

b. Description: creation of passage through abdominal wall into ileum

c. Psychosocial concerns

(1) Acceptance of stoma and stoma care

(2) Concerns related to social and physical activities

4. Continent ileostomy (Kock pouch or Barnett continent intestinal reservoir)

a. Purpose: create a reservoir for feces after total proctocolectomy

b. Description: construction of an intestinal reservoir created by joining a loop of terminal ileum and forming a nipple valve; after healing is complete, patient controls expulsion of feces and gas by emptying reservoir or pouch with catheter.

c. Postanesthesia phase I priorities

(1) Maintain patency of decompression tube after creation of continent ileostomy; gently irrigate pouch with normal saline solution (30 mL every 3 hours is commonly ordered).

(2) Surgically created pouch is fragile until healed and matured because of many anastomoses.

5. Small bowel resection

a. Purpose: treat

(1) Trauma

(2) Mesenteric thrombosis

(3) Regional enteritis

(4) Radiation enteropathy

(5) Strangulated small bowel obstruction

(6) Neoplasm

(7) Congenital atresia

(8) Enterocutaneous fistulas

b. Description: excision of varying lengths of small intestine; profound consequences with resection of more than 75% of small intestine (e.g., “short-gut” syndrome)

(1) In general, patients need 150 cm of small intestine without their ileocecal valve or 100 cm of small intestine with their ileocecal valve.

(2) Less small intestine than this generally results in “short-gut” syndrome and the need for supplemental total parenteral nutrition.

E. Colon or large intestine

1. Abdominoperineal resection

a. Purpose

(1) Generally performed for cancer of rectum

(2) Occasionally for severe Crohn’s, especially in the presence of severe perianal disease

b. Description: surgical procedure in which anus, rectum, and sigmoid colon are removed en bloc through incision extending from pubis to above umbilicus

(1) Segment of lower bowel mobilized and divided

(2) Proximal end exteriorized through separate stab wound as a single-barreled colostomy or ileostomy

(3) Distal end pushed into hollow of sacrum, and rectum removed through perianal route via a perineal incision

c. Preoperative assessment and concerns

(1) Patients may experience significant dehydration subsequent to extensive bowel preparation.

d. Complications

(1) Ureter or bladder injury

(2) Wound dehiscence or infection

2. Cecostomy

a. Purpose: temporary measure to relieve obstruction distal to cecum

b. Description: construction of opening into cecum, generally by placing a tube

3. Colectomy

a. Purpose: treat

(1) Tumors

(2) Bleeding

(3) Inflammation

(4) Trauma of large intestine

b. Description: surgical removal of all or part of colon

4. Restorative proctocolectomy (total proctocolectomy with ileal reservoir and anal anastomosis)

a. Purpose

(1) Maintain the anal sphincter muscles and allow the patient to avoid a permanent ileostomy

(2) Patient with a good to excellent result has 4 to 12 bowel movements per day.

(3) Used for selected patients with ulcerative colitis or familial polyposis coli

b. Description: pouch made from terminal ileum is created and then anastomosed to rectum at or just above dentate line; J-shaped ileoanal or larger W-shaped reservoir is most common; also S shaped

5. Colostomy

a. Purpose: incision of colon to create fistula between bowel and abdominal wall

b. Description

(1) Either temporary or permanent

(2) Placement of ostomy site is individualized.

(3) Location depends on:

(a) Pathological condition involved

(i) Transverse colostomy

(ii) Sigmoid colostomy

(b) Patient’s anatomy and lifestyle

(4) Mucous fistula may also be created for decompression of cancer-caused obstruction of lower colon.

6. Low anterior resection

a. Purpose: treat malignancies of rectosigmoid area or diverticulitis.

b. Description

(1) Rectum-containing tumor excised

(2) Rectal stump and proximal bowel anastomosed either with suture or with staples

7. Omphalocele (excision): rare defect of periumbilical abdominal wall seen primarily in premature infants; omphalocele sac may contain small and/or large bowel, liver, or spleen.

a. Primary closure

(1) Purpose: used for omphaloceles with small abdominal defects

(2) Description: omphalocele sac excised, and abdominal wall muscles and skin edges reapproximated.

b. Staged repair

(1) Purpose: used for large omphaloceles

(2) Description: omphalocele is encased in silicone elastomer mesh sack that is sutured in place around defect; viscera are gradually moved into abdominal cavity in stages.

c. Preoperative assessment and concerns

(1) Often associated with other anomalies

(2) Decompression of stomach to prevent regurgitation or aspiration

d. Intraoperative concerns

(1) Closure may be primary or staged depending on size of defect, abdominal tension.

e. Postanesthesia phase I priorities

(1) Patients with large defects may remain intubated and mechanically ventilated.

(2) Fluid management

f. Psychosocial concerns

(1) Parental support

g. Complications

(1) Circulatory and renal dysfunction

(2) Infection

8. Polypectomy

a. Purpose: to remove isolated gastrointestinal polyps

b. Description: using snare and electrocautery, polyps removed endoscopically; large polyps may require open colectomy.

F. Rectal and anal procedures

1. Transanal excision of polyps or masses

a. Purpose: to remove polyps or masses from the anal or rectal areas

b. Description: excision of polyps or masses using a transanal approach

2. Lateral internal sphincterotomy

a. Purpose: to treat chronic anal fissures

b. Description: cutting of anal sphincter; anoplasty normally required to reestablish anal tissue and mucosal integrity

c. Botulinum toxin injection is an alternative procedure that is done without anesthesia.

3. Anal fistulotomy or fistulectomy

a. Purpose: treat, by either incision or excision, fistulous tracts in anal canal.

b. Description: infection of anal duct gland creates fistula in ano.

(1) May be incised and drained or excised and packed to heal by granulation

(2) Usually has presenting condition of a perianal abscess, which is incised and drained

(3) Chronic draining tract may develop, which communicates with the anal canal.

(4) Treated with fistulotomy (opening the fistula) if not deep and crossing the sphincters

(5) If deep and cross multiple sphincters, more complicated anorectal procedures required to repair the defect

4. Duhamel and Soave operations

a. Purpose: treat congenital megacolon (Hirschsprung’s disease) in children.

b. Description: in both Duhamel and Soave procedures:

(1) Aganglionic bowel resected

(2) Proximal, healthy colon pulled through and anastomosed to rectum

c. Preoperative assessment and concerns

(1) Present with prior colostomy

(2) Mildly malnourished with associated malabsorption state

(3) Diarrhea may be present.

d. Intraoperative concerns

(1) Potential for large third-space losses

e. Postanesthesia phase I priorities

(1) Continuous epidural analgesia for pain management

VI. GENERAL POSTANESTHESIA CARE CONCERNS

A. Routine immediate postanesthesia assessment following American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses Standards of Perianesthesia Nursing Practice and American Society of Anesthesiologists Standards for Postanesthesia Care

B. General postanesthesia observation and care for gastrointestinal procedures

1. Cardiovascular system

a. Monitor vital signs per unit routine; check perfusion to extremities.

(1) Risk for radical shifts in body fluids as result of:

(a) Inadequate fluid replacement

(b) Excessive replacement

(c) Preoperative status

(d) Presence of fistula

(e) Vomiting

(f) Diarrhea

(g) Intestinal obstruction

(h) Third spacing

(i) Nasogastric drains and tubes

(2) Sequestered fluid in gastrointestinal tract resulting from:

(a) Tumor

(b) Stricture

(c) Adhesions

(d) Paralytic ileus

(e) Surgical manipulation

(3) Sequestered fluid is lost to circulating volume of body.

(a) It is in a potential or “third” space.

(b) Third-space fluid generally does not begin to mobilize until second or third postoperative day.

(4) Stress responses resulting in hormonal alterations can lead to retention of fluids and potential for fluid overload postoperatively.

b. Observe for hemostasis; observe for and document coagulation deficiencies.

(1) Oozing

(2) Bruising

(3) Petechiae

(4) In patients with a history of coagulation problems or those who have received massive transfusions, coagulation difficulties can occur.

(5) Clotting also affected by:

(a) Malabsorption

(b) Impaired digestion

(c) Altered liver function

c. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

(1) Formation is potential complication of immobility.

(2) Laparoscopic procedures increase risk of emboli as result of:

(a) Air insufflation

(b) Resultant increase in intra-abdominal pressure

(c) Decreasing venous return, particularly from the lower extremities

(3) Prevention

(a) Leg exercises

(b) Range of motion (ROM) at least every hour as part of “stir-up” regimen

(c) Antiembolism stockings

(d) Intermittent pneumatic or sequential compression devices

(e) Low-dose anticoagulation as ordered

(4) Active ROM exercises stimulate venous return from extremities.

2. Genitourinary system

a. Monitor intake and output every hour and specific gravity every 4 hours.

(1) Potential for decreased urine output as result of fluid shifts

b. Assess bladder distention if no indwelling catheter in place.

(1) Bladder distention is common postoperative problem.

(2) Palpation of bladder or bladder ultrasound may be used.

c. Note color of urine.

(1) Retraction or pressure placed on bladder or kidney during surgery can traumatize bladder or kidney.

3. Endocrine system

a. Document blood glucose levels, urine glucose, and ketones as appropriate.

(1) Surgical intervention and operative stress on body systems alter pancreatic enzymes and insulin production.

(a) Patients with diabetes are observed for same reasons.

(2) Blood glucose can be monitored with point-of-care blood glucose checks

4. Respiratory system

a. Document routine postanesthesia nursing interventions (“stir-up” or “wake-up” regimens) and their results concerning:

(1) Lung auscultation

(2) Deep breathing

(3) Incentive spirometry

(4) Coughing to mobilize and expectorate secretions

(5) Turning

(6) ROM exercises

(7) Prevention of decreased lung expansion leading to:

(a) Atelectasis

(b) Congestion

(c) Hypostatic pneumonia

(8) Reasons for decreased lung expansion

(a) Oversedation

(b) Lack of sedation

(c) Hypoxia

(d) Fluid overload

(e) Decreased ventilatory excursion

b. If central line (central venous or pulmonary artery catheter) is placed intraoperatively or in PACU, obtain chest film.

(1) Demonstration of correct catheter placement

(2) Confirmation of presence or absence of pneumothorax

c. Document chest drainage and chest tube function.

(1) Follow PACU routine for care of chest tubes for patients undergoing pulmonary approach for upper gastrointestinal surgery.

(a) Esophageal resection

(b) Hiatal herniorrhaphy

5. Gastrointestinal system

a. NPO

(1) Nausea and vomiting may be present because of effects of:

(a) Anesthesia

(b) Decreased intestinal motility

(c) Malfunctioning nasogastric tube

(d) Disease process

b. Nasogastric tube assessment

(1) Check for proper tube placement by auscultating with stethoscope over gastric area while inserting 20 to 50 mL air into tube.

(a) If nasogastric tube was placed intraoperatively under direct visualization:

(i) Check with surgeon before irrigating or repositioning.

(ii) If tube is properly placed, rush of air should be heard.

(2) Secure tube to nares with correct taping technique.

(a) Taping or securing tube properly decreases:

(i) Risk of necrosis or damage of nares

(ii) Inadvertent dislodgment of tube

(iii) Alar necrosis is disfiguring and difficult to repair if it occurs.

c. Maintain patency of nasogastric or gastrostomy tube.

(1) To decrease tension on gastric suture line

(2) Notify surgeon of excessive drainage from tubes or drains so that IV fluid and rates can be adjusted.

(3) Initial 24-hour drainage may be bloody, changing to dark serosanguineous to bile colored over the next 24 to 72 hours.

(4) Color and consistency vary with location of surgery.

(a) If esophageal or gastric surgery, expect bloody drainage.

(b) If hepatic, biliary, or intestinal surgery, drainage should not be bloody.

d. Irrigation or manipulation of nasogastric tubes

(1) Do not irrigate or manipulate nasogastric tube unless specifically ordered.

(a) Nasogastric tube lies close to anastomosis (gastric resection, some pancreatic procedures involving stomach).

(2) Check, if nasogastric tube to dependent drainage, for proper securing of tube to eliminate manipulation.

(a) Nasogastric tube may be used as stent anastomosis in esophageal procedures.

(3) Notify surgeon if nasogastric tube is accidentally removed or becomes displaced.

(a) Attempts to replace tube can result in esophageal perforation.

e. Assess abdominal girth (abdominal distention), and auscultate bowel sounds.

(1) Abdominal distention, nausea, and vomiting may be caused by:

(a) Anastomotic leak

(b) Hemorrhage

(c) Malfunctioning nasogastric tube

(d) Ileus

(e) Mechanical obstructions

f. Observe and document status of:

(1) Stoma color

(a) Notify surgeon of any sudden or progressive change in stoma color.

(b) Altered color may indicate increasing edema, leading to:

(i) Decreased circulation

(ii) Generalized poor circulation to bowel

(2) Drainage from stoma

(3) Position of stoma to skin

6. Dressings and drains

a. Document dressing status every hour or as needed.

(1) Keeping dressing dry promotes wound healing by minimizing potential breeding ground for bacterial contamination.

b. Reinforce or change dressing per preferred routine or as ordered.

(1) Dry dressings more comfortable for patient

c. Monitor amount of drainage on dressings and from drains.

(1) Establish expected drainage amounts with surgeon when patient arrives in PACU.

(2) Notify surgeon of excessive or questionable quantities of drainage.

(3) Significant blood or fluid losses can occur from incisions or drain sites that may require replacement or exploration of site.

d. Document both abdominal and perineal dressings after abdominoperineal resection.

(1) Sump or Penrose (cigarette or tube) drains may be present in perineal incision, a likely area for copious serosanguineous drainage.

7. Positioning

a. Lateral recumbent position

(1) Side-lying position is usually more comfortable for patients who have had rectal or perineal procedures.

b. Elevate head of the bed (reverse Trendelenburg, not head up and hips flexed).

(1) Elevating head decreases weight against diaphragm to:

(a) Promote improved respiratory excursion.

(b) Facilitate gas exchange.

8. Temperature

a. Monitor temperature on admission to PACU.

b. Warm or cool patient as indicated with:

(1) Warming lights

(2) Hypothermia or hyperthermia blankets

(3) Convective warming devices

c. Vital signs should include temperature monitoring on PACU admission and every 1 to 2 hours until discharge.

d. Avoid rectal temperatures with:

(1) Permanent colostomies

(2) Ileostomies

(3) Rectal or anal incisions

(4) After pull-through or stapled low anterior resections

(5) Perforation of suture or staple lines is possible if rectal or anal incision exists or if rectum has been totally removed.

9. Pain control (see Chapter 26)

a. Assessment

(1) Location

(2) Pattern

(3) Intensity

(4) Duration of pain

(5) If possible, use pain assessment tool.

(a) Requires patient to identify quality of pain or discomfort

(6) Initiate pain relief measures.

(7) Medicate patients according to PACU routine and approved pain guidelines.

b. Pain management practices will vary from institution to institution.

(1) Pain is subjective; patient complaining of pain should be believed and comfort measures initiated.

c. Observe for incisional splinting.

(1) Splinting can lead to increased partial pressure of carbon dioxide (P co 2) level because of inadequate gas exchange.

d. IV route preferred for opioid and analgesic administration

(1) Absorption time and onset of action less predictable when intramuscular injections administered in cold patient

e. In selected patients, pain relief can be significant from:

(1) Patient-controlled analgesia

(2) Epidural analgesia

(3) Incisional or field blocks

f. Adequate pain control may improve:

(1) Ventilation

(2) Promote deep breathing and coughing.

(3) Allow patient to move more easily, especially after procedures with large or upper abdominal incisions.

g. Pain generally related to incision type

(1) Midline incisions less painful than transverse or chevron incisions

(2) Upper midline incisions more painful than lower midline incisions

C. Phase II priorities

1. Pain management

a. Initiate oral analgesics to prepare for discharge.

b. Instruct patients to call if:

(1) Pain unrelieved by oral medications

(2) Has severe pain

(3) Questions related to pain (amount, location, duration)

2. Diet

a. Encourage fluids if desired; do not force fluids.

b. Instruct patients to begin with light foods and progress to full diet as tolerated.

c. If nauseated or vomiting for more than 6 hours after discharge, instruct patients to call and report nausea and vomiting.

3. Wound care

a. Review basic wound care with patients, companions, and families.

b. Provide written and verbal instructions, especially for specialized incisional and/or drain care.

c. Instruct patients to call if incision shows signs of infection or a fever is present.

4. Activity

a. Generally, activities limited first day postoperatively

b. Dependent on operative procedure, lifting and activity restrictions may be ordered.

5. Complications

a. Provide patient, family, and responsible accompanying adult with information on expected outcomes and complications.

b. Instruct in appropriate follow-up if needed for complications.

D. Postoperative complications

1. General complications (not in order of occurrence or severity)

a. Paralytic (adynamic) ileus: although commonly listed as a complication, it is an expected part of any abdominal or intestinal procedure; all patients who have these procedures will experience ileus.

b. Atelectasis and respiratory problems

c. Bladder distention

d. Hemorrhage or shock

e. Wound infection

f. Dehiscence or evisceration

g. Peritonitis

h. Hiccups (singultus)

i. Anastomotic leak

j. Anastomotic or stomal obstruction

k. Intestinal fistulas

l. Electrolyte and fluid imbalances

m. Stress ulceration

n. DVT and possible pulmonary embolus

o. Pancreatitis

p. Toxic shock syndrome

2. Specific system complications

a. Pulmonary

(1) Hypoventilation: most frequent and dangerous pulmonary complication after surgery; various causes

(a) Preoperative medication

(b) Anesthetic agents

(c) Opioid, sedative administration

(i) Preoperative

(ii) Intraoperative

(iii) Postoperative

(d) Pain

(e) Patient position

(2) Atelectasis: constitutes 90% of all pulmonary complications

(a) Acute gastric dilation or ascites in advanced cancer can cause elevation of diaphragm, leading to decreased size of chest cavity and atelectasis (can also lead to shock).

(b) Postoperative splinting resulting from incisional pain is the most common cause of atelectasis.

b. Cardiovascular

(1) Venous thrombosis

(2) Hypotension

(3) Shock

(a) Hypovolemic

(b) Septic

(4) Myocardial infarction

(5) Cerebrovascular accident

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Complications of upper GI endoscopy, Gastrointest Endosc 55 (7) ( 2002) 784–793.

2. Ball, K.A., Endoscopic surgery: Mosby’s perioperative nursing series. ( 1997)Mosby, St Louis.

3. Black, J.M.; Hawks, J.H., Medical-surgical nursing: Clinical management for positive outcomes. ed 7 ( 2005)Saunders, St Louis.

4. Guyton, A.C., Human physiology and mechanisms of disease. ed 5 ( 1996)WB Saunders, Philadelphia.

5. Hulka, J.F.; Reich, H., Textbook of laparoscopy. ed 3 ( 1998)WB Saunders, Philadelphia.

6. Jaffe, R.A.; Samuels, S.I., Anesthesiologist’s manual of surgical procedures. ed 3 ( 2004)Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.

7. Moody, F.G.; Carey, L.C.; Jones, R.S.; et al., Surgical treatment of digestive disease. ed 2 ( 1990)Mosby, Chicago.

8. O’Brien, D., Care of the gastrointestinal, abdominal, and anorectal surgical patient, In: (Editors: Drain, C.B.; Odom-Forren, J.) Perianesthesia nursing: A critical care approached 5 ( 2009)WB Saunders, Philadelphia.

9. O’Brien, D.; Walters, V.A.; Burden, N., Special procedures in the ambulatory setting, In: (Editors: Burden, N.; Quinn, D.M.D.; O’Brien, D.; et al.) Ambulatory surgical nursinged 2 ( 2000)WB Saunders, Philadelphia.

10. O’Hanlon-Nichols, T., Book assessment series: Gastrointestinal system, Am J Nurs 98 (4) ( 1998) 48–52.

11. Patton, K.T.; Thibodeau, G.A., Anatomy & physiology. ed 7 ( 2010)Mosby, St Louis.

12. Rakel, R.E.; Bope, E.T., Conn’s current therapy. ed 60 ( 2008)Saunders, Philadelphia.

13. Ray, S., Result of 310 consecutive patients undergoing laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication as hospital outpatients or at a free-standing surgery center, Surg Endosc 17 (2003) 378–380.

14. Roizen, M.F.; Fleisher, L.A., Essence of anesthesia practice. ed 2 ( 2002)WB Saunders, Philadelphia.

15. Sommers, M.S.; Johnson, S.A.; Beery, T.A., Diseases and disorders: A nursing therapeutics manual. ed 3 ( 2007)FA Davis, Philadelphia.

16. Standring, S., Gray’s anatomy: The anatomical basis of clinical practice. ( 2009)Churchill Livingston, Philadelphia.

17. Suter, M.; Giusti, V.; Heraief, E.; et al., Laparoscopic roux-en-Y gastric bypass, Surg Endosc 17 (2003) 603–609.

18. Thompson, J.; McFarland, G.; Hirsch, J.; et al., Mosby’s clinical nursing. ed 5 ( 2002)Mosby, St Louis.

19. Tilkian, S.M.; Conover, M.H.; Tilkian, A.G., Clinical nursing implications of laboratory tests. ed 5 ( 1996)Mosby, St Louis.

20. Townsend, C.M.; Beauchamp, R.D.; Evers, B.M.; et al., Sabiston textbook of surgery. ed 18 ( 2007)Saunders, Philadelphia.

21. Widmaier, E.; Raff, H.; Strang, K., Vander’s human physiology. ed 9 ( 2003)McGraw-Hill, New York.

22. Wiegand, D.J.L.M.; Carlson, K.K., AACN procedure manual for critical care. ed 5 ( 2005)Saunders, St Louis.