History

Comments

Current Medications

Comments

Current Symptoms

FIGURE 34-1 Preextraction electrocardiogram.

Comments

Physical Examination

Comments

Laboratory Data

Comments

Electrocardiogram

Findings

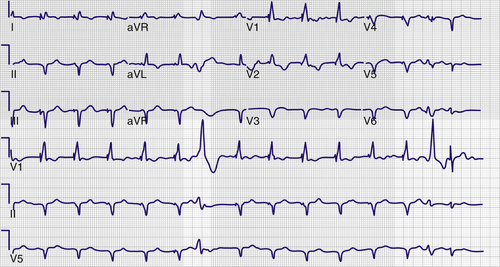

Chest Radiograph

Findings

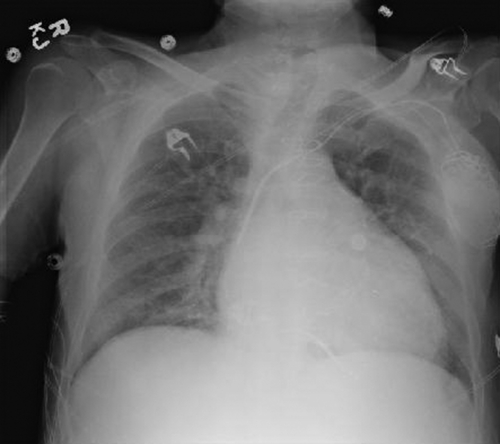

Echocardiogram

Findings

FIGURE 34-2 Portable chest radiograph showing the Starfix coronary venous lead in the midventricular position.

FIGURE 34-3 Transesophageal echocardiogram depicting a vegetation on the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator lead as it crosses the tricuspid valve.

Comments

Focused Clinical Questions and Discussion Points

Question

Discussion

Question

Discussion

Question

Discussion

Question

Discussion

Final Diagnosis

Plan of Action

Intervention

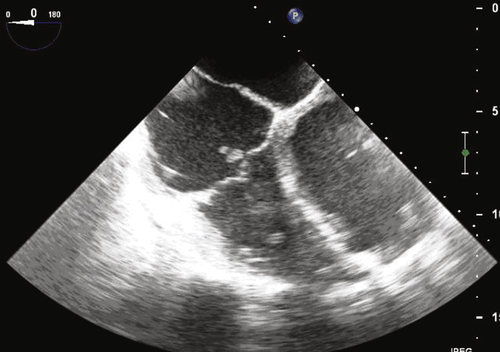

FIGURE 34-4 Tissue ingrowth into the lobes of the Starfix coronary venous lead preventing undeployment.

Outcome

Findings

Comments

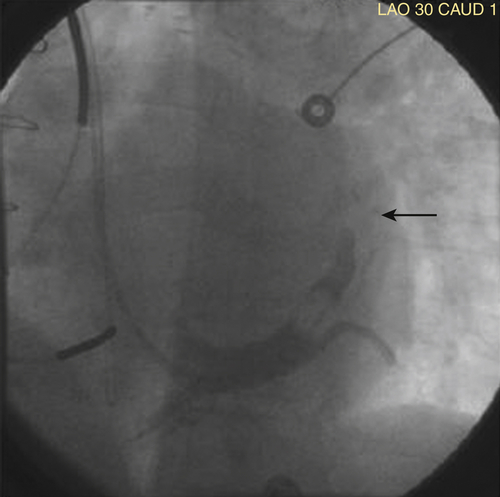

FIGURE 34-5 Occlusion of venous branch from which the Starfix coronary venous lead was extracted.

Selected References

1. Baddour L.M., Epstein A.E., Erickson C.C. et al. Update on cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections and their management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;3:458–477.

2. Baranowski B., Yerkey M., Dresing T. et al. Fibrotic tissue growth into the extendable lobes of an active fixation coronary sinus lead can complicate extraction. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2011;7:e64–e65.

3. Bongiorni M.G., Zucchelli G., Soldati E. et al. Usefulness of mechanical transvenous dilation and location of areas of adherence in patients undergoing coronary sinus lead extraction. Europace. 2007;1:69–73.

4. Burke M.C., Morton J., Lin A.C. et al. Implications and outcome of permanent coronary sinus lead extraction and reimplantation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;8:830–837.

5. Chua J.D., Wilkoff B.L., Lee I. et al. Dagnosis and management of infections involving implantable electrophysiologic cardiac devices. Ann Intern Med. 2000;8:604–648.

6. Maytin M., Carrillo R.G., Baltodano P. et al. Multicenter experience with transvenous lead extraction of active fixation coronary sinus leads. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2012;6:641–647.

7. Rickard J., Tarakji K., Cronin E. et al. Cardiac venous left ventricular lead removal and reimplantation following device infection: a large single-center experience. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012;23:1213–1216.

8. Rickard J., Wilkoff B.L. Extraction of implantable cardiac electronic devices. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2011;13:407–414.

9. Sheldon S., Friedman P.A., Hayes D.L. et al. Outcomes and predictors of difficulty with coronary sinus lead removal. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2012;35:93–100.

10. Wilkoff B.L., Love C.J., Byrd C.L. et al. Transvenous lead extraction: Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus on facilities, training, indications, and patient management. Heart Rhythm. 2009;7:1085–1104.