History

Current Medications

First Intervention

Outcome

Second Intervention

Outcome

Third Intervention

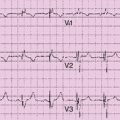

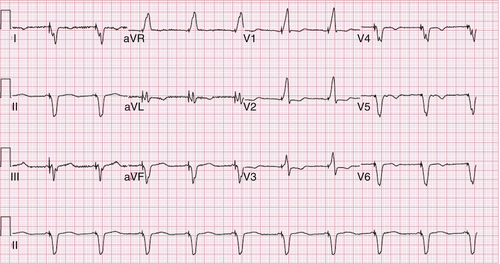

FIGURE 33-1 Patient with left bundle branch block pattern in electrocardiogram.

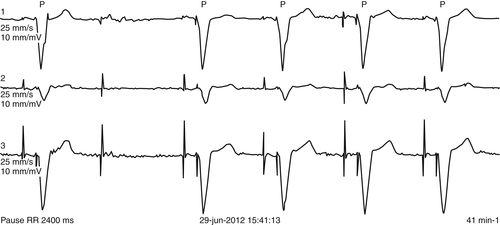

FIGURE 33-2 Patient with intermittent ventricular oversensing resulting from electrical failure of a Riata lead (St. Jude Medical).

Outcome

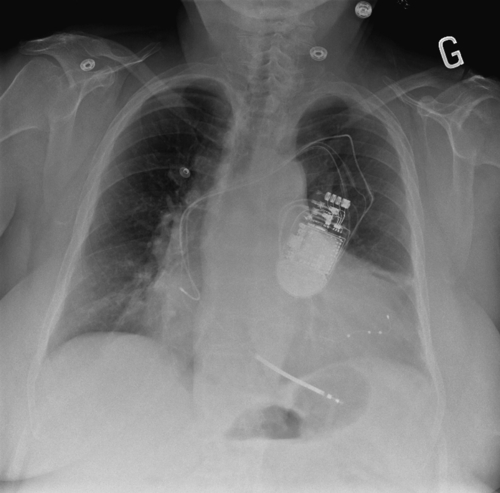

FIGURE 33-3 A posteroanterior chest radiograph is shown depicting the position of the three implanted leads, including a quadripolar left ventricular lead (Quartet, St. Jude Medical) deeply inserted in the lateral branch of the coronary sinus.

Focused Discussion Points

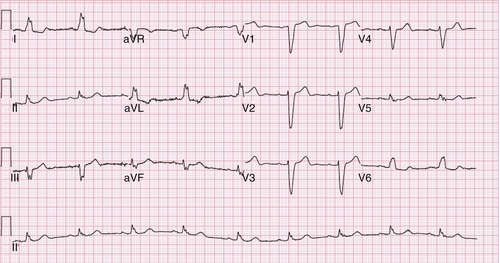

FIGURE 33-4 Patient with effective biventricular pacing shown in electrocardiogram.

Selected References

1. Biffi M., Boriani G. Phrenic stimulation management in CRT patients: are we there yet? Curr Opin Cardiol. 2011;26:12–16.

2. Biffi M., Exner D.V., Crossley G.H. et al. Occurrence of phrenic nerve stimulation in cardiac resynchronization therapy patients: the role of left ventricular lead type and placement site. Europace. 2013;15:77–82.

3. Biffi M., Moschini C., Bertini M. et al. Phrenic stimulation: a challenge for cardiac resynchronization therapy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:402–410.

4. Champagne J., Healey J.S., Krahn A.D. et al. The effect of electronic repositioning on left ventricular pacing and phrenic nerve stimulation. Europace. 2011;13:409–415.

5. Forleo G.B., Mantica M., Di Biase L. et al. Clinical and procedural outcome of patients implanted with a quadripolar left ventricular lead: early results of a prospective multicenter study. Heart Rhythm. 2012;11:1822–1828.

6. Klein N., Klein M., Weglage H. et al. Clinical efficacy of left ventricular pacing vector programmability in cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator patients for management of phrenic nerve stimulation and/or elevated left ventricular pacing thresholds: insights from the efface phrenic stim study. Europace. 2012;14:826–832.

7. Maytin M., Carrillo R.G., Baltodano P. et al. Multicenter experience with transvenous lead extraction of active fixation coronary sinus leads. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2012;35:641–647.

8. Poole J.E., Gleva M.J., Mela T. et al. Complication rates associated with pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator generator replacements and upgrade procedures: results from the replace registry. Circulation. 2010;122:1553–1561.

9. Shetty A.K., Duckett S.G., Bostock J. et al. Use of a quadripolar left ventricular lead to achieve successful implantation in patients with previous failed attempts at cardiac resynchronization therapy. Europace. 2011;13:992–996.

10. Sperzel J., Danschel W., Gutleben K.J. et al. First prospective, multi-centre clinical experience with a novel left ventricular quadripolar lead. Europace. 2012;14:365–372.

11. Thibault B., Karst E., Ryu K. et al. Pacing electrode selection in a quadripolar left heart lead determines presence or absence of phrenic nerve stimulation. Europace. 2010;12:751–753.