Manual Self-Inflating Resuscitation Bag-Valve Device

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Bagging is an essential skill used in emergency situations, such as cardiopulmonary arrest. Bagging also is indicated for the following:

To provide oxygenation and ventilation before and after suctioning airway procedures and during patient transports

To provide oxygenation and ventilation before and after suctioning airway procedures and during patient transports

To assess airway patency and proper airway device placement

To assess airway patency and proper airway device placement

To evaluate the interaction of patient and ventilator

To evaluate the interaction of patient and ventilator

To alter the ventilatory pattern

To alter the ventilatory pattern

Bagging should result in chest movement and auscultatory evidence of bilateral air entry.

Bagging should result in chest movement and auscultatory evidence of bilateral air entry.

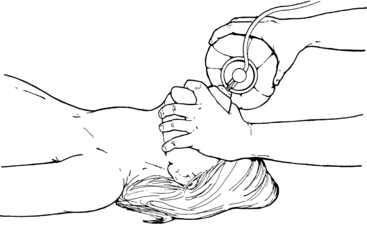

In patients without an artificial airway in place, effective bagging requires an unobstructed airway, slight head and neck hyperextension (i.e., the same technique used for mouth-to-mouth ventilation), and firm placement of the face mask over the nose and mouth (Fig. 32-1). An exception to this technique is with known or suspected cervical spine injury, in which the patient’s airway is opened with the chin-lift method (without neck hyperextension). Effective bagging is best accomplished with two people: one to secure the mask and ensure head and neck placement and one to bag.1 In patients with artificial airways, such as endotracheal or nasotracheal tubes or tracheostomies, the nurse must understand the components of artificial airways and their relationship to the upper airway anatomy (see Procedures 1, 2, 3, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 14, 18).

In patients without an artificial airway in place, effective bagging requires an unobstructed airway, slight head and neck hyperextension (i.e., the same technique used for mouth-to-mouth ventilation), and firm placement of the face mask over the nose and mouth (Fig. 32-1). An exception to this technique is with known or suspected cervical spine injury, in which the patient’s airway is opened with the chin-lift method (without neck hyperextension). Effective bagging is best accomplished with two people: one to secure the mask and ensure head and neck placement and one to bag.1 In patients with artificial airways, such as endotracheal or nasotracheal tubes or tracheostomies, the nurse must understand the components of artificial airways and their relationship to the upper airway anatomy (see Procedures 1, 2, 3, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 14, 18).

When signs and symptoms of respiratory distress are noted in a patient on mechanical ventilation, the patient should be bagged on 100% oxygen if troubleshooting the ventilator does not immediately solve the problem. Large bagged breaths or rapid rates during bagging may result in dynamic hyperinflation and resultant hypotension.2,3 Hyperinflation occurs when exhalation time is inadequate, which results in auto–positive end-expiratory pressure (auto-PEEP) and decreased venous return (see Procedure 30), with the resultant hypotension. Dynamic hyperinflation is most commonly associated with bronchospasm and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.2 A high index of suspicion for the presence of dynamic hyperinflation is necessary if hypotension occurs with bagging. A brief disconnection from the bag or the provision of longer exhalation times or both results in a rapid increase in blood pressure. Bagging is resumed at a slower rate and with longer expiratory times.

When signs and symptoms of respiratory distress are noted in a patient on mechanical ventilation, the patient should be bagged on 100% oxygen if troubleshooting the ventilator does not immediately solve the problem. Large bagged breaths or rapid rates during bagging may result in dynamic hyperinflation and resultant hypotension.2,3 Hyperinflation occurs when exhalation time is inadequate, which results in auto–positive end-expiratory pressure (auto-PEEP) and decreased venous return (see Procedure 30), with the resultant hypotension. Dynamic hyperinflation is most commonly associated with bronchospasm and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.2 A high index of suspicion for the presence of dynamic hyperinflation is necessary if hypotension occurs with bagging. A brief disconnection from the bag or the provision of longer exhalation times or both results in a rapid increase in blood pressure. Bagging is resumed at a slower rate and with longer expiratory times.

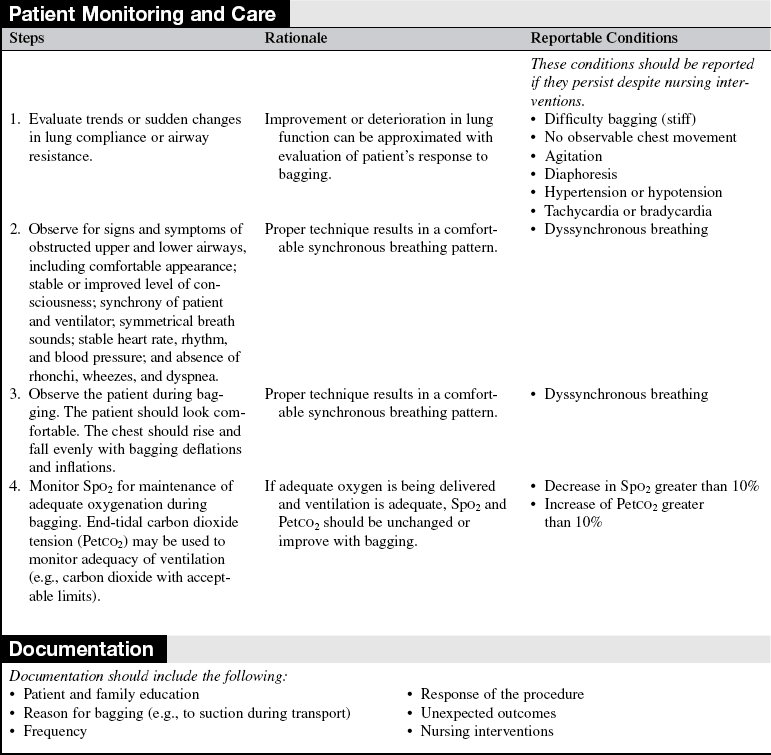

EQUIPMENT

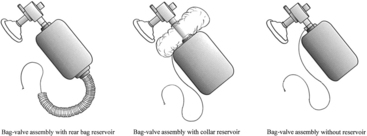

• Manual self-inflating resuscitation bag-valve device (of appropriate size) (Fig. 32-2) and appropriately sized mask

• Oxygen source, flow regulator, and tubing

• PEEP valve or PEEP attachment (if patient on greater than 10 cm H2O of PEEP)

• Personal protective equipment (i.e., gloves, mask, goggles, gown, as appropriate)

Additional equipment to have available depending on patient need:

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Inform the patient and family that the patient needs assisted breathing and, if currently on a ventilator, the patient will be disconnected from the ventilator and bagging will be performed. Describe the reason (e.g., suctioning, transporting, patient comfort) for bagging and explain that if the patient is dyspneic or otherwise distressed, bagging must be done immediately.  Rationale: Information about the patient’s therapy is an important need of patients and family members. Dyspnea is uncomfortable and frightening. It leads to anxiety, fear, and distrust. Failure to diagnose promptly and alleviate the cause of respiratory distress puts the patient at risk for further decompensation.

Rationale: Information about the patient’s therapy is an important need of patients and family members. Dyspnea is uncomfortable and frightening. It leads to anxiety, fear, and distrust. Failure to diagnose promptly and alleviate the cause of respiratory distress puts the patient at risk for further decompensation.

• Inform the patient and family that the patient may be in different positions during bagging (i.e., side-lying, prone, supine, Trendelenburg’s, reverse Trendelenburg’s, semi-Fowler). Bagging may be more difficult, however, if the diaphragm and abdominal contents are in positions that resist lung inflation.  Rationale: Positioning is not an impediment to bagging as long as an intact airway is in place. Bagging may be more difficult in some positions.

Rationale: Positioning is not an impediment to bagging as long as an intact airway is in place. Bagging may be more difficult in some positions.

• Discuss the sensory experience associated with bagging.  Rationale: Knowledge of anticipated sensory experiences decreases anxiety and distress.

Rationale: Knowledge of anticipated sensory experiences decreases anxiety and distress.

• Instruct the patient to communicate discomfort with breathing during bagging.  Rationale: The bagging technique can be altered to produce a comfortable breathing pattern.

Rationale: The bagging technique can be altered to produce a comfortable breathing pattern.

• Offer the opportunity for the patient and family to ask questions about bagging.  Rationale: The ability to ask questions and have questions answered honestly is cited consistently as the most important need of patients and families.

Rationale: The ability to ask questions and have questions answered honestly is cited consistently as the most important need of patients and families.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

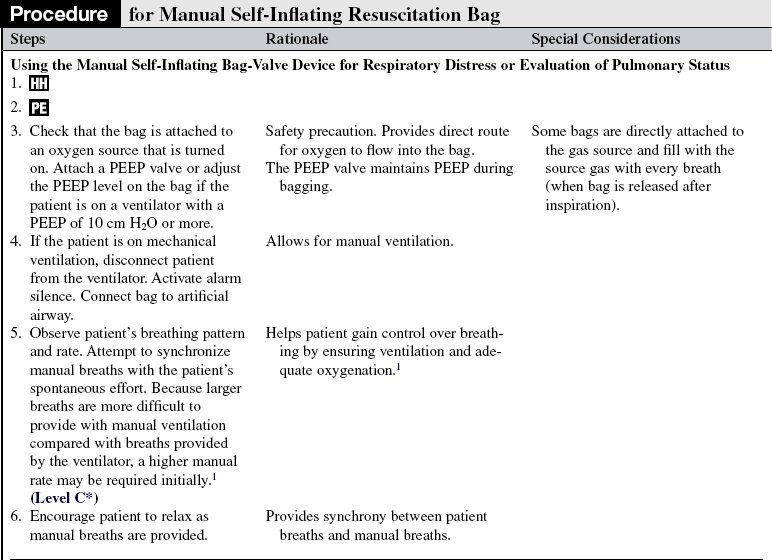

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Determine oxygenation and ventilation status and observe for the following signs:

Sudden decrease in arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2)

Sudden decrease in arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2)

Sudden decrease in pulse oximetry saturation (SpO2)

Sudden decrease in pulse oximetry saturation (SpO2)

Rationale: Any acute change in patient status may indicate that bagging is necessary.

Rationale: Any acute change in patient status may indicate that bagging is necessary.

Rapid response with 100% FiO2 protects the patient and allows for rapid evaluation of airway resistance, placement and function of artificial airway, and interaction of patient and ventilator.

Rapid response with 100% FiO2 protects the patient and allows for rapid evaluation of airway resistance, placement and function of artificial airway, and interaction of patient and ventilator.

• Determine airway resistance (how easily air moves down the airways) and lung compliance (how easily the lungs and chest wall distend).  Rationale: Airway resistance and lung compliance can be assessed by bagging the patient with breaths that are similar in volume and rate to the breaths provided by the ventilator. Focus on the degree of ease (or difficulty) with which the bag is compressed during inspiration. If bagging the patient is difficult, look for causes of high airway resistance (e.g., obstructed airway, bronchospasm) or low lung compliance (e.g., mucus obstruction, pulmonary edema, pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, pneumothorax). Compare findings with findings after interventions, such as suctioning and bronchodilator use. Changes in resistance and compliance can be confirmed by evaluating dynamic characteristic and static compliance when the patient is placed back on the ventilator (see Procedure 31).

Rationale: Airway resistance and lung compliance can be assessed by bagging the patient with breaths that are similar in volume and rate to the breaths provided by the ventilator. Focus on the degree of ease (or difficulty) with which the bag is compressed during inspiration. If bagging the patient is difficult, look for causes of high airway resistance (e.g., obstructed airway, bronchospasm) or low lung compliance (e.g., mucus obstruction, pulmonary edema, pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, pneumothorax). Compare findings with findings after interventions, such as suctioning and bronchodilator use. Changes in resistance and compliance can be confirmed by evaluating dynamic characteristic and static compliance when the patient is placed back on the ventilator (see Procedure 31).

• Ensure proper placement and function of the artificial airway (see Procedures 1, 2, 3, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 14).  Rationale: The positioning and patency of the airway are ensured.

Rationale: The positioning and patency of the airway are ensured.

• Evaluate interaction of patient and ventilator and specifically note dyssynchrony of patient and ventilator by observing for the following:

Breathing pattern not in synchrony with ventilator breaths

Breathing pattern not in synchrony with ventilator breaths

Altered level of consciousness

Altered level of consciousness

Rationale: Bagging may aid in the return of a synchronous breathing pattern and recognition of the cause (e.g., obstruction). If signs and symptoms persist despite bagging, other causes (e.g., pulmonary embolus) should be considered. Therapeutic interventions to ensure synchrony and effective oxygenation and ventilation may be necessary and may include administration of medications such as sedatives, narcotics, and bronchodilators. Additional diagnostic evaluations also may be needed (e.g., bronchoscopy, ventilation-perfusion scans, computed tomography–pulmonary angiography [CT-PA]).

Rationale: Bagging may aid in the return of a synchronous breathing pattern and recognition of the cause (e.g., obstruction). If signs and symptoms persist despite bagging, other causes (e.g., pulmonary embolus) should be considered. Therapeutic interventions to ensure synchrony and effective oxygenation and ventilation may be necessary and may include administration of medications such as sedatives, narcotics, and bronchodilators. Additional diagnostic evaluations also may be needed (e.g., bronchoscopy, ventilation-perfusion scans, computed tomography–pulmonary angiography [CT-PA]).

Patient Preparation

• Ensure that the patient understands pre-procedural teachings, or if the patient’s condition precludes teaching, assure the patient that bagging will help with less shortness of breath. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: This communication evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

Rationale: This communication evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

References

![]() 1. Grap, MJ, et al, Endotracheal suctioning. ventilator vs manual delivery of hyperoxygenation breaths. Am J Crit Care 1996; 5:192–197.

1. Grap, MJ, et al, Endotracheal suctioning. ventilator vs manual delivery of hyperoxygenation breaths. Am J Crit Care 1996; 5:192–197.

![]() 2. Pepe, PE, Marini, JJ. Occult positive end-expiratory pressure in mechanically ventilated patients with airflow obstruction. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982; 126:166–170.

2. Pepe, PE, Marini, JJ. Occult positive end-expiratory pressure in mechanically ventilated patients with airflow obstruction. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982; 126:166–170.

3. Pierce, LNB, Administration of oxygen humidification, and aerosol therapy. Management of the mechanically ventilated patient. ed 2. Elsevier, St Louis, 2007.