CHAPTER 3. Patient and Family Education

Valerie S. Watkins

OBJECTIVES

At the conclusion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Define the education process and use the nursing process to provide patient and family education (assessment, nursing diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation).

2. Define The Joint Commission (TJC) standards for patient and family education.

3. Identify the developmental stages of learner.

4. List patient education that addresses the five teaching domains.

5. List components of patient teaching using the three domains of learning.

6. Describe teaching strategies that meet the needs of patients with different learning styles.

7. Describe methods for evaluation of patient education.

8. Identify documentation and information obtained from evaluations to improve the education process.

I. TJC STANDARDS FOR PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

A. TJC’s rationale for patient and family education is to provide patients sufficient information to make decisions and take responsibility for self-management and activities related to their needs.

B. Expectations (Box 3-1)

BOX 3-1

THE JOINT COMMISSION 2009 STANDARD

Provision of Care

The hospital provides patient education and training based on each patient’s needs and abilities.

Elements of Performance

▪ The hospital performs a learning needs assessment for each patient, which includes the patient’s cultural and religious beliefs, emotional barriers, desire and motivation to learn, physical or cognitive limitations, and barriers to communication.

▪ The hospital provides education and training to the patient based on his or her assessed needs.

▪ The hospital coordinates the patient education and training provided by all disciplines involved in the patient’s care, treatment, and services.

▪ Based on the patient’s condition and assessed needs, the education and training provided to the patient by the hospital include any of the following:

▪ An explanation of the plan for care, treatment, and services

▪ Basic health practices and safety

▪ Information on the safe and effective use of medications

▪ Nutrition interventions (for example, supplements) and modified diets

▪ Discussion of pain, the risk for pain, the importance of effective pain management, the pain assessment process, and methods for pain management

▪ Information on oral health

▪ Information on the safe and effective use of medical equipment or supplies provided by the hospital

▪ Habilitation or rehabilitation techniques to help the patient reach maximum independence

▪ The hospital evaluates the patient’s understanding of the education and training it provided

From The Joint Commission: Comprehensive accreditation manual for ambulatory care (CAMAC), Oakbrook Terrace, IL, 2009, The Joint Commission.

C. TJC is not looking for evidence of what is taught but what the patient knows.

II. ASSESSMENT

A. Assessing learning needs

1. Defined as gaps in knowledge that exist between desired level of performance and actual level of performance

a. Gaps exist because of a lack of knowledge, attitude, or skills.

b. Identify the learner.

c. Choose the right setting.

d. Collect data about the learner.

e. Collect data from the learner.

f. Involve members of the health care team.

g. Prioritize needs.

h. Determine the availability of educational resources.

i. Access demands of the organization.

j. Take time-management issues into account.

B. Readiness to learn: willingness or ability to accept information

1. Assessment of readiness to learn

a. Physical readiness

(1) Measures of ability

(2) Complexity of task

(3) Environmental effects

(4) Health status

(5) Gender

(6) Primary language

b. Emotional readiness

(1) Anxiety level

(2) Support system

(3) Motivation

(4) Risk-taking behavior

(5) Frame of mind

(6) Developmental stage

c. Experimental readiness

(1) Level of aspiration

(2) Past coping mechanism

(3) Cultural background

(4) Locus of control

(5) Orientation

d. Knowledge readiness

(1) Present knowledge base

(2) Cognitive ability

(3) Learning disabilities

(4) Learning styles

C. Assessing learning styles

1. Visual: learn through seeing.

a. Like to see the big picture or diagrams

b. To coincide with the verbal instructions, prefer

(1) Demonstrations

(2) Watching videos

(3) Written material

2. Auditory: Learn through hearing.

a. Like to listen to

(1) Audio tapes

(2) Lectures

(3) Debates

(4) Discussion

(5) Verbal instructions

3. Kinesthetic: learn through physical activities and through direct involvement.

a. Like to be “hands-on,” moving, touching, experiencing

b. Will respond well to hands-on learning with equipment and return demonstration of skills

4. Determine learning style (way that individual processes information).

a. Adults

(1) Use more than one method of learning

(2) Have a primary learning preference

b. Children have a more defined preference for one of the learning styles.

c. May need to use more than one method to provide information

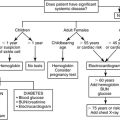

D. Developmental stages of learner: specific patient population requirements will have bearing on ability to learn and interact

1. Age-specific—infant, child, adolescent, adult, and geriatric

a. Emotional, cognitive, communication, educational

b. Developmental age—not just age of patient

2. Are there any developmental delays or injuries that may have impacted the ability to learn?

a. Family’s, significant other’s, or guardian’s expectations for and involvement in care

b. Emotional or behavioral disorders

c. Alcoholism or drug dependency

d. Possible victims of abuse or neglect

e. Patients with history of posttraumatic stress disorder or previous unpleasant experiences

f. Cultural preferences

g. Past and present health care practices

h. Language barriers

(1) Legislation requires the use of qualified interpreters for limited English proficiency patients representing the largest minority group in the area.

(2) The patient has the option of declining the interpreter and using a family member or friend, but this must be documented on the patient record.

(3) Qualified interpreters must be used for all “life-threatening” information (unless declined by the patient) such as

(a) Diagnosis

(b) Patient histories

(c) Surgical procedures

(d) Medical procedure

(e) Procedural consents

(f) Discharge instructions

(4) Information can be taken and given over the phone via an authorized interpreter if the interpreter is not available to come to the hospital or facility site.

E. Stress

1. Can be physiological, psychological, or emotional

2. Some individuals are more vulnerable than others.

3. Responses can be behavioral, psychological, or physiological.

4. Children are more vulnerable when a number of stressors are present.

5. Identify behaviors indicative of stress.

6. Must listen to children—be aware of fears and concerns.

7. Physical comforting and reassuring are beneficial to children.

F. Coping: individual reactions to stressors

1. Strategies are specific to the person.

2. Styles are relatively unchanging personality characteristics or outcomes of coping.

3. Children have a more internal center of control.

4. Strategies that use relaxation are effective in reducing stress.

G. Pediatric concerns when addressing educational needs (see Chapter 10)

1. Pediatric stages of growth and development

2. Psychosocial development (Erikson)

a. Experiences can be favorable or unfavorable.

b. Birth to 1 year (trust vs mistrust)

(1) Establishment of trust dominates.

(2) Trust exists in relationship to someone or something.

c. One to 3 years (autonomy vs shame and doubt)

(1) Autonomy is centered on the children’s increased ability to control their bodies, themselves, and their environments.

(2) Children want to do things for themselves by using newly acquired motor skills.

(a) Walking

(b) Climbing

(c) Mental powers of selection and decision-making

(3) Much of learning is acquired through imitation of activities and behavior.

(4) Negative feelings arise when

(a) Made to feel small and self-conscious

(b) Consequences of behavior and choices are negative

(c) Shamed by others

(d) Forced to be dependent in areas where independence has been demonstrated

d. Three to 6 years (initiative vs guilt)

(1) Characterized by energetic and intrusive behavior and a strong imagination; explore the world with all of their senses and abilities.

(2) No longer guided by outsiders; develop a conscience that warns and protects or threatens them.

(3) A sense of guilt occurs when in conflict with others or made to feel that their behaviors are bad.

(4) Must learn to maintain initiative without encroaching on the rights of others.

e. Six to 12 years (industry vs inferiority)

(1) Want to engage in activities and behaviors that they can complete. They need a sense of achievement.

(2) They learn to compete and cooperate with others, and learn the rules.

(3) Important for learning to develop relationships with others.

(4) May feel inadequate and inferior if too much is expected of them or they believe they cannot measure up to standards set for them by others.

f. Twelve to 18 years (identity vs role confusion)

(1) Adolescent-development is characterized by rapid and marked physical changes.

(2) Adolescents’ perception of their bodies changes and diminishes.

(3) They become overly preoccupied with others’ perceptions of themselves.

(4) Adolescents face difficulty in dealing with concepts that others expect of them and the values of society.

3. Cognitive development (Piaget)

a. Consists of age-related changes that occur in mental activities.

b. Intelligence enables individuals to make adaptations to the environment that increase the probability of survival.

c. Three stages of reasoning

(1) Intuitive

(2) Concrete operational

(3) Formal operational

d. Concrete reasoning for children begins at about 7 years of age.

e. Birth to 2 years (sensorimotor)

(1) Six substages that are governed by sensations

(2) Progress from simple reflex activity to simple repetitive behaviors to imitative behavior

(3) Develop a sense of cause and effect

(4) Display a high level of curiosity, experimentation, and enjoyment of new things

(5) Begin to develop a sense of self; become aware of a sense of permanence

(6) Begin to use language and thought

f. Two to 7 years (preoperational)

(1) Interpret objects in sense of relationships or the use to themselves. Unable to see things from any perspective but their own

(2) See things in sense of concrete and tangible; lack the ability to use deductive reasoning

(3) Use imaginative play, questioning, and other interactions to develop the ability to make associations between ideas

(4) Thought is dominated by what children see, hear, or experience. Have increasing use of language and symbols to represent objects in their environment

g. Seven to 11 years (concrete operations)

(1) Become increasingly logical and articulate

(2) Able to sort, classify, order, and organize information to use in problem solving

(3) Develop a new concept of permanence

(4) Able to deal with multiple aspects of a situation simultaneously

(5) Do not have the ability to deal with abstract concepts

(6) Problems are solved in concrete systematic methods based on what children recognize.

(7) Become less self-centered through interactions with others; thinking becomes socialized

(8) Can consider points of view outside their own

h. Eleven to 15 years (formal operations)

(1) Able to be adaptable and flexible

(2) Can think in abstract terms and symbols, and are able to draw logical conclusions from observations

(3) Can make hypotheses and test them

(4) Consider abstract, theoretical, and philosophical matters

(5) May confuse the ideal with the practical, but in most cases can deal with the contradictions and resolve issues

(6) Nonsocial stimulating experience that starts outside the child

(7) Attention attracted by objects in the environment

(a) Light

(b) Color

(c) Taste

(d) Odors

(e) Textures

(f) Consistencies

(8) Use of body senses to experience

H. Fears

1. Vary with age

a. Infants

(1) Birth to 6 months: loss of support, loud noise, bright lights, sudden movement

(2) Seven to 12 months: strangers, sudden appearance of unexpected and looming objects, animals, or heights

b. Toddlers (1–3 years): separation from parents, the dark, loud or sudden noise, injury, strangers, certain persons (e.g., the physician), certain situations (e.g., trip to the dentist), animals, large objects or machines, change in environment

c. Preschoolers (3–5 years): separation from parent, supernatural beings (e.g., monsters or ghosts), animals, the dark, noises, “bad” people, injury, death

d. School-age children (6–12 years): supernatural beings, injury, storms, the dark, staying alone, separation from parent, things seen on television or in movies, injury, tests and failure in school, consequences related to unattractive physical appearance, death

e. Adolescents: inept social performance, social isolation, sexuality, drugs, war, divorce, crowds, gossip, public speaking, plane and car crashes, death

I. Adult concerns when addressing educational needs

1. Early adulthood: 20 to 40 years (intimacy vs isolation)

a. Have a commitment to work and relationships

(1) Have they planned appropriately for the impact that surgery may have on their work, social, and personal life?

b. Concerned with emancipation from parents and in building an independent lifestyle

c. Concerned with forming an intimate bond with another and choosing a mate

(1) The adult seeks love, commitment, and industry of an intense, lasting relationship.

(2) Relationships include mutual trust, cooperation, acceptance, sharing of feelings and goals.

(3) Without secure personal identity, the adult cannot form a love relationship; may result in a lonely, isolated, withdrawn person.

d. Has reached maximum potential for growth and development

e. All body systems operate at peak efficiency.

f. Nutritional needs depend on maintenance and repair requirements and on activity levels.

g. Sensible nutrition is a major problem for many adults.

h. Cognitive function has reached a new level of formal operations and the capacity for abstract thinking.

i. Less egocentric, operates in a more realistic and objective manner

j. Is close to the maximum ability to acquire and use knowledge

k. Work is an important factor in the young adult and is tied closely with ego identity.

l. Begins to self-reflect in the late 20s to early 30s:

(1) “Where am I going?”

(2) “Why am I doing these things in my life?”

m. The 30s are characterized by settling down.

n. Strives to establish a niche in society and to build a better life

o. Risk for stress is increased since there are many situations that require choices to be made.

p. Single parents often have additional stress of decreased financial resources for themselves and/or children.

2. Middle adulthood: 40 to 64 years (generativity vs stagnation)

a. Realization that life is half over

b. Accepting and adjusting to the physical changes of middle age

(1) Effects of aging are becoming more apparent—wrinkles, graying or thinning hair, changes in body function, redistribution of fat deposits, decreased physical stamina and abilities.

(2) Decreased respiratory capacity and cardiac function, visual changes

(3) Sensory function remains intact except for some visual changes (e.g., decreased accommodation for near vision or presbyopia)

(4) Women—menopause:

(a) Decrease in estrogen and progesterone

(b) Attendant symptoms of

(i) Atrophy of reproductive organs

(ii) Hot flashes

(iii) Mood swings

(5) Men: decrease in testosterone, which causes

(a) Decreased sperm and semen production

(b) Less intense orgasms

c. Adjusting to aging parents

d. Reviewing and redirecting career goals

e. Helping adolescent children in their search for identity

(1) Often feel caught in a “squeeze” between simultaneously changing needs of adolescent children and aging parents

f. Accepting and relating to the spouse as a person

g. Coping with an empty nest at home

h. Aware of occasional death of peers—reminder of own mortality

i. Leading causes of death: cardiovascular disease, cancer, and stroke

j. Morbidity increased

(1) Often related to increase in obesity

(2) Resulting hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, mobility dysfunction, and arthritis

(3) Chronic smoking leads to health problems.

k. Intelligence levels remain generally constant.

(1) Is further enhanced by knowledge that comes with

(a) Life experiences

(b) Self-confidence

(c) A sense of humor

(d) Flexibility

(2) Interested in how new knowledge is applied, not just in learning for learning’s sake

l. Adults have an urge to contribute to the next generation.

(1) Wants to be needed, to leave something behind

(2) If fulfillment does not occur, stagnation is experienced—boredom, a sense of emptiness in life, which leads to being inactive, self-absorbed, self-indulgent, a chronic complainer.

m. Role realignment occurs in relationships with aging parents.

(1) Once parents die, middle-aged adults are more vulnerable and realize limited quantities of time are left.

n. Be alert for

(1) Depressive symptoms

(2) Suicide risk factors

(3) Abnormal bereavement

(4) Signs of physical abuse or neglect

(5) Malignant skin lesions

(6) Peripheral arterial disease

(7) Other body dysfunction

(8) Signs and symptoms apply to young and late adulthood.

3. Maturity—65 years to death (integrity vs despair)

a. Fastest growing segment of the population

b. Developmental tasks include:

(1) Adjusting to changes in physical strength and health

(2) Forming a new family role as an in-law and/or a grandparent

(3) Adjusting to retirement and reduced incomes

(4) Developing postretirement activities that enhance self-worth and usefulness

(5) Arranging satisfactory physical living quarters

(6) Adjusting to the death of spouse, family members, and friends

(7) Conducting a life review

(8) Preparing for the inevitability of one’s own death

c. Illness affects aging people more than those in other age groups.

(1) Incidence of chronic disease increases.

(2) Resistance to illness decreases.

(3) Recuperative power decreases.

(4) Body aches and pains increase.

(5) Increasingly dependent on the health care system for advice, health teaching, and physical care

d. Widely diverse response to disease and health concerns is dependent on

(1) Subjective attitude

(2) Physical activity

(3) Nutrition

(4) Personal habits

(5) Occurrence of physical illness

e. Intellectual function depends on factors such as

(1) Motivation

(2) Interest

(3) Sensory impairment

(4) Educational level

(5) Deliberate caution

(6) Tendency to conserve time and emotional energy rather than acting assertively

f. Decreased ability for complex decision-making

(1) Do not provide information for more than one task at a time. (2)Giving a list of directions produces confusion and inability to follow-through.

g. Decreased speed of performance—requires more time to process and to complete tasks

h. Memory may be affected.

(1) If so, short-term memory more so than long-term memory

i. Retirement often involves financial adjustment.

(1) May impact ability to manage disease processes if money is not available for medications or food

j. Options to live alone may change as ability to care for self decreases.

k. Reminded of limited time remaining as aging continues

(1) Life review occurs.

l. Feels content with life or has feelings of futility, despair, resentment, hopelessness, and a fear of death

m. Decreased ability to read materials in normal or small font size

n. Loses ability to read materials printed in or on backgrounds of green and blue

J. Consider options for obtaining information.

1. Informal conversations

2. Questionnaires

3. Observations

4. Structured interviews

a. Telephone

b. Face to face

5. Focus groups

6. Patient charts

7. Risk management reports

8. Committee requests

9. Professional society standards or requirements

10. Changes in patient populations

11. Patterns of care delivery

12. Regulatory requirements

K. Consider barriers in assessment.

1. Cultural

2. Religious

3. Physical limitations

4. Cognitive limitations

5. Language

6. Financial barriers

7. Consider your own biases.

a. Ethnicity

b. Religion

c. Elderly

d. Alcohol use

e. Obesity

f. Children

g. Female/male hang-ups

h. The key to developing education to meet the needs of the patient requires nurses to understand their own biases and how they affect their views and the care they provide.

L. Start with what the learner knows.

1. Determine what the patient, family, or significant other feels that they need to know.

a. Collect data from the patient, family, or significant other.

2. Educational background and primary language

3. Cultural factors

a. “Do you seek the advice of another health practitioner?”

b. “Do you use herbs or other medications or treatments?”

c. “What language do you use most often when speaking and writing?”

4. What knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes does the patient have?

III. NURSING DIAGNOSIS

A. Analyze assessment. Identify potential problems.

1. Preoperative

a. Knowledge deficits, absence or deficiency of cognitive information

(1) Process issues

(2) Safety issues

(3) Risks for injury, infection

(4) Anxiety

(5) Hypothermia or hyperthermia

(6) Potential coping inability, ineffective coping

(7) Ineffective or absent support system

(8) Body image disturbance

(9) Caregiver role strain

(10) Risk for altered development

(11) Fears

(12) Fluid volume deficits

(13) Latex allergy risk or problem

(14) Impaired mobility

(15) Pain management concerns (acute and chronic)

(16) Nutritional deficits and concerns

2. Postoperative

a. Knowledge deficits and risks for developing problems

(1) Airway management problems

(2) Safety concerns

(3) Hypothermia or hyperthermia

(4) Nutritional concerns and needs

(5) Altered mental status

(6) Activity intolerance or inability

(7) Aspiration risk

(8) Body image disturbance

(9) Caregiver role strain

(10) Communication impaired

(11) Risk for altered, delayed, or regressed development

(12) Altered family processes

(13) Fear

(14) Fluid volume deficit or excess

(15) Grieving

(16) Latex allergy risk or problem

(17) Impaired mobility

(18) Nausea and vomiting

(19) Impaired memory

(20) Ineffective pain management (acute and chronic)

(21) Nutritional concerns and deficits

(22) Impaired skin integrity

(23) Altered sleep patterns and inadequate sleep

(24) Impaired tissue integrity

(25) Urinary elimination concerns

(26) Altered sexuality

(27) Risk for development of constipation

3. Determine specific problems of patient and family or significant other.

4. Nursing diagnosis may be formal or informal.

a. May be incorporated into a care process model or map

5. Diagnosis may be related to altered health responses or dysfunction.

a. May be anticipated or actual problems

B. May use the teaching-learning process

1. Similar to nursing process

a. Assessing learning needs and learning readiness

b. Developing learning objective. Objectives must be specific, attainable, measurable, and short-term statements.

c. Planning and implementing patient teaching

d. Evaluating patient learning

2. Documenting patient teaching and learning

3. Both processes repeat with ongoing assessment and evaluation, redirecting the planning and teaching.

IV. PLANNING

A. Develop a teaching plan based on learning outcomes/objectives to meet the patient’s needs.

1. Address immediate and emerging needs—explain rationale for what will be occurring.

a. Physical

b. Psychological

c. Social

d. Nutritional status

e. Functional status

f. Pain

g. Necessary diagnostic tests based on patient’s diagnosis and condition—not routine testing

h. Discharge planning

2. Starts at first contact with patient and progresses through each additional contact

3. Develop learning objectives.

a. Desired outcomes

(1) State the desired patient behavior or performance.

(2) Reflect an observable, measurable activity.

(3) May add conditions or modifiers as required to clarify what, where, when, or how the behavior will be performed.

(4) Include criteria specifying the time by which learning should have occurred.

b. Learning objectives can reflect the learner’s command of simple to complex concepts.

c. Must be specific about what behaviors and knowledge (cognitive, psychomotor, affective) the learner must have to accomplish the desired outcome. Examples:

(1) Describe signs and symptoms of wound infection.

(2) Identify equipment needed for wound care.

(3) Describe appropriate actions if questions or complications arise.

4. Select specific content to be addressed.

5. Motivation for learning. Set realistic goals as a motivating factor.

a. Internal is more lasting and more self-directive.

b. Need for learning is recognized.

(1) Five learning principles

(a) Principle 1: learning is influenced by personal factors, such as past experiences, culture, age, ability to learn, and beliefs about health.

(b) Principle 2: students learn more when they perceive a need to learn and when they have a clear overview of the plan.

(c) Principle 3: learning is facilitated when the learner is accepted and respected as a person of worth in a mutually trusting relationship without fear of criticism or ridicule.

(d) Principle 4: people learn through their five senses: seeing, hearing, feeling, smelling, and tasting.

(e) Principle 5: learning is facilitated when students have knowledge of how well they are performing in a learning experience.

(2) Patients who are ill do not absorb information well—this improves as health returns.

c. Encourage motivation.

(1) Provide nonthreatening environment.

(2) Encourage self-direction and independence.

(3) Demonstrate a positive attitude about patient’s ability to learn.

(4) Offer continuing support and encouragement as attempts are made to learn.

(5) Create learning situations in which the patient is likely to succeed.

B. Consider the patient as an individual with specific needs, abilities, values, knowledge, and skills.

1. Prioritize needs.

a. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs provides a guideline for determining patient needs.

(1) Physiological needs (basic needs)

(2) Safety and security needs (freedom from fear)

(3) Belonging and love needs (give and receive affection)

(4) Esteem needs (need to be perceived as competent)

(5) Self-actualization needs (need to fill one’s potential)

b. Involve patient and family in determining what they consider important to learn.

2. Determine availability of resources.

a. Focus on what is available and what information can be provided to patient and family for present and/or future use.

b. Internet

(1) Expect that patients have already searched for information.

(2) Be aware of the information available.

(3) Be prepared to teach your patients how to access information and what sites are most reliable.

(4) Use as a teaching tool through your health care organization.

(5) Be aware that most patient information is written at a 10th grade level.

3. Consider time-management issues.

a. What can be provided in the time frame available?

b. Minimize distractions.

4. Teach basics before progressing to more difficult concepts.

5. Allow time for questions and review of contents for clarification.

C. Develop patient education that addresses the five teaching domains.

1. Situational and procedural information

a. Provide description of what to expect of the perioperative experience.

b. Examples:

(1) Explain process—preoperatively, intraoperatively, postoperatively.

(2) Who will patient come into contact with?

(3) Timing of events

(4) Family’s or significant other’s role in process

(5) Children—what parental or guardian role is, when parent or guardian will leave child and when will return

2. Sensation and discomfort information

a. What the patient may feel, see, and hear

b. Examples:

(1) “What will occur?” “How will you feel?”

(2) Environmental description, uniforms, masks

(3) Pain management

(4) Anxiety

(5) “What will you hear?”

(a) Hearing is last sense to leave.

(b) Hearing is first sense to return.

(c) May hear things even if not completely awake

3. Patient role information

a. Behavior expectation

b. Examples

(1) Explain procedures and follow-up.

(2) ”Nothing by mouth” (NPO) guidelines, including medications to take and to hold

(3) Home preparations and care needs after discharge for self and/or family

(4) Appropriate clothing for discharge

(5) Need for safe transportation home after discharge

4. Skills training

a. Explanation of specific skills needed postoperatively

b. Examples:

(1) Teach skills (e.g., how to do a dressing change, empty drains, management of pain).

5. Psychosocial support

a. Interaction between patient and the care providers

b. Examples:

(1) Assist in decision-making.

(2) Reinforce what may already be known.

(3) Change: provide alternative behaviors or thoughts.

(4) Maximize current level of functioning.

D. Develop components of patient teaching using the three domains of learning.

1. Affective and attitude learning (feeling domain)

a. Addresses attitudes, behaviors, and feelings

b. Most difficult domain in which to affect learning

2. Psychomotor learning (skills/doing domain)

a. Motor skills

b. Best taught by demonstration and hands-on experiences

c. Provide the opportunity to practice.

d. Return demonstration (e.g., use of incentive spirometer, crutch walking demonstration and practice)

3. Cognitive learning (thinking domain)

a. Addresses the patient’s understanding

b. Incorporates use of facts, details, and information basic to intellectual learning

c. Multiple methods best address this learning need.

d. People remember:

(1) 10% of what they read

(2) 20% of what they hear

(3) 30% of what they see

(4) 50% of what they see and hear

(5) 90% of what they say and do

4. Select teaching strategies to be used based on information obtained in needs assessment.

a. Explanation (cognitive)

b. One-to-one discussion (affective, cognitive)

c. Answering questions (cognitive)

d. Demonstration (psychomotor)

e. Discovery (cognitive, affective)

f. Group discussions (affective, cognitive)

g. Practice (psychomotor)

h. Printed and audiovisual materials (cognitive)

i. Role playing (affective, cognitive)

j. Modeling (affective, psychomotor)

k. Computer-assisted learning programs (all types of learning)

E. Suitability of education materials used for patients

1. Use of printed material is an economical one

2. Allows the patient to proceed at own pace

3. Use of a variety of media is more successful

4. Disadvantages

a. One in five adults is functionally illiterate, reading at or below the fifth grade level.

(1) Because of shame and embarrassment, patients rarely admit they are functionally illiterate.

b. Research shows that low literacy and poor health care are closely related.

c. Five percent of the population cannot read English.

d. Many individuals who are illiterate have normal or above-average intelligence.

5. Many computer programs have built-in features that will calculate the readability of your document.

6. Tell the patients what they need to know, not what is nice to know.

F. Strategies for improving readability

1. Writing

a. Reading materials should be at a fifth grade or lower reading level.

b. Vocabulary—use short words.

(1) Use simple, smaller words.

(2) Use words of less than three syllables.

c. Define words that are difficult to understand.

d. Do not use abbreviations or acronyms.

e. Sentence construction—use short sentences, no more than 10 to 20 words.

(1) Avoid the use of medical terminology; use lay terminology—explain in terms the patient and family can understand.

(2) Active voices (present tense)—avoid passive voice.

(3) It is more easily understood.

(4) Conversational style, use you and your.

(5) Put most important information first.

(6) If possible, make the first word the topic of the sentence and the first sentence of the paragraph the topic sentence.

2. Design

a. Typography

(1) Type size and font make text easy or difficult to read at all levels.

(2) Select simple type style (serif or sans serif).

(3) Type size is at least 12 point.

(4) Use typographic cues (boldface, size, color) to emphasize key points.

(5) Avoid ALL CAPS, italics, or fancy lettering.

(6) Justify text to left, leave right side jagged.

b. Headers, subheadings, or captions

(1) Helps the reader to focus attention on the message

(2) Use both lowercase and uppercase letters.

(3) Less than seven independent items—more easily remembered

(4) Three to five items for lower literacy levels

c. Layout

(1) Layout and sequence of information are consistent, easy to predict flow.

(2) Visual cuing devices (shading, boxes, arrows) are used to direct attention to specific points or key content.

(3) Allow for plenty of white space.

(4) Use of color supports and is not distracting from the message. Do not use pastels.

(5) Line length is 30 to 50 characters and spaces.

(6) High contrast between paper and type

(7) Paper has nongloss or low-gloss surface.

(8) Use of bullets helps, especially when summarizing

d. Graphics (illustrations, lists, tables, charts, graphs)

(1) Material is judged by first impression.

(2) Friendly, attractive, and clearly portrays intent of material

e. Type of illustration

(1) Illustrations are on the same page adjacent to the text.

(2) Use design layouts that allow eye movement from left to right, as in reading.

(3) Simple line drawings promote realism without distracting details.

(4) Avoid medical textbook drawings or abstract art or symbols.

f. Relevance of illustrations

(1) Use to illustrate concepts or procedures

(a) Keep simple

(2) Avoid nonessential details such as room background, elaborate borders, and unneeded color.

g. Graphics

(1) If used, must have clear explanations (step by step, or how-to instructions)

(2) Easily misunderstood

h. Captions

(1) Can quickly tell a reader what the graphic is about and where to focus

(2) Brief and simple

V. IMPLEMENTATION

A. Teaching is performed using specific methods of instruction and tools.

1. Optimal time for learning depends primarily on the learner.

2. Pace of the teaching session affects learning.

3. Environment selected must be conducive to learning.

a. Avoid distractions (i.e., noise and interruptions).

4. Teaching aids can foster learning and help focus learner’s attention.

5. Learning is more effective when learners discover the content for themselves.

a. Provide stimulating motivation and stimulating self-direction.

b. Provide feedback.

6. Repetition reinforces learning.

7. Organize information ahead of time.

8. Use lay person’s vocabulary.

9. Teaching strategies

B. Use specific teaching strategies.

1. Group teaching

2. Computer-assisted instruction

3. Discovery and problem solving

4. Behavior modification

C. Develop teaching strategies that meet the needs of patients with different learning styles.

D. Role of play in development

1. Play has therapeutic and moral value and assists in development of

a. Sensorimotor skills

b. Intellectual development

c. Socialization

d. Creativity

e. Self-awareness

2. Content of play

a. Social-affective play

(1) Takes pleasure in relationships with people

(2) Starts with smiling and cooing, progresses to initiating games and activities

(3) Varies among cultures

b. Sense-pleasure play

c. Skill play

(1) Repeat actions over and over

(2) Determination to accomplish and develop new skills may produce a sense of frustration and pain.

d. Unoccupied behavior

(1) Not playful, but focus attention on anything that strikes the children’s interest

(2) Daydream, fiddle with clothes or other objects, or walk aimlessly

e. Dramatic or pretend play

(1) Dramatic or symbolic play begins in late infancy (11–13 months).

(2) Predominant form of play in preschool child

(3) As interactions with others increase, children attribute meaning to activities.

(4) Acting out daily events provides modeling of behaviors of family and members of society.

(5) Interacting with the environment develops a greater understanding of the world.

f. Games

(1) Found in all cultures

(2) Repetitive activities allow progression to more complicated games and activities.

(3) Challenge development of independent skills: puzzle solving, playing solitaire, computer or video games

(4) Different ages participate in different games—simple to more complex.

(5) Preschoolers hate to lose and will try to cheat or change the rules, or demand exceptions.

(6) School-age children and adolescents enjoy competitive games—mental and physical.

E. Transcultural teaching

1. Obtain teaching materials, pamphlets, and instructions in various languages used by patients in the health care setting.

a. Use a translator to evaluate materials.

2. Use visual aids, such as pictures, charts, or diagrams, to communicate meaning.

a. Audiovisual material may help portray the intent of simple information.

3. Use concrete rather than abstract words.

a. Use simple language—short sentences, short words.

b. Present only one idea at a time.

4. Allow time for questions.

5. Avoid the use of medical terminology.

6. If understanding another’s pronunciation is a problem, validate a brief meaning in writing.

7. Use humor cautiously.

8. Do not use slang words or colloquialisms.

9. Do not assume that a patient who nods, uses eye contact, or smiles is indicating an understanding of what is being taught.

10. Invite and encourage questions during teaching.

11. When explaining procedures or functioning related to personal areas of the body, it might be appropriate to have a nurse of the same sex do the teaching.

12. Include the family in the planning and teaching.

13. Consider the patient’s time orientation.

14. Identify cultural health practices and beliefs.

a. Provide education to patient in preferred language.

b. Provide written materials in preferred language.

15. Provide documentation of education to patient and family.

a. Verbally

b. Written form

16. Provide patients with information about available resources that will facilitate habilitation or rehabilitation.

17. Promote the patient education process among appropriate staff and disciplines that are providing care or services.

18. Care is planned for and coordinated by the facility providing the patient services.

VI. EVALUATION

A. Develop methods of evaluation for patient education materials and processes.

1. Both an ongoing and final process

2. Evaluate achievement of desired outcomes.

a. Established by patient, family, significant other, and nursing collaboration

b. Learning objectives and goals of education directed by nursing diagnosis

(1) Cognitive learning demonstrated by acquisition of knowledge that directly impacts behavior changes

(2) Psychomotor learning is best evaluated by observing how well the client carries out a procedure.

(3) Affective learning is more difficult to observe. May be evaluated by determining

(a) Whether patient has made changes to behaviors that will improve long-term health status

(b) Patient obtaining health education that impacts long-term health

3. Evaluation of content

a. Purpose

(1) Is it clearly stated?

(2) Is it clearly understood?

b. Content topics

(1) That which is of greatest interest will become focus of patient efforts.

c. Scope

(1) Limited to purpose or objectives

d. Summary and review

(1) Reinforces and reiterates information addressed

4. Learning stimulation and motivation

a. Interaction included in text and/or graphic

(1) Chemical changes occur when the patient responds to the questions.

(2) Memory is enhanced and retention occurs.

(3) Moves to long-term memory

(4) Ask to solve problems, to make choices, or to demonstrate.

b. Desired behavior patterns are modeled, shown in specific terms.

(1) People learn more readily by observation and by doing it themselves, rather than by being told.

c. Motivation

(1) More motivated to learn when the tasks or behaviors are doable

(2) Divide complex tasks into small parts—will experience small successes in understanding or problem solving.

5. Cultural appropriateness

a. Cultural match: logic, language, experience (LLE)

(1) Does the LLE match the intended audience?

b. Cultural image and examples

(1) Present cultural images and examples in a realistic and positive way.

6. Evaluate the effectiveness of the teaching that was provided by the nurse.

a. Consider all factors of the teaching experience.

(1) Timing

(2) Teaching strategies

(3) Amount of information provided

(4) Was the teaching helpful?

(5) Was the patient, family, or significant other overwhelmed by the amount or type of information?

(6) Request feedback from the patient, family, and significant other.

(7) Were the needs of the patient considered when providing the education?

(8) Were the patient’s preferences for learning considered in providing the education?

7. Use information obtained from evaluations to improve the education process.

8. Effectiveness of education is evaluated by changes in behavior, knowledge attained, attitudes, and skills development.

9. Methods of evaluation

a. Concurrent and retrospective

(1) Self-report of patient, family, or significant other

(2) Direct observation

(3) Retain copy of materials provided to patient.

10. Methods of measurement

a. Defined quality indicators that determine patient outcomes

b. Observation

c. Interview

d. Checklist

e. Written or oral testing

f. Patient demonstrates comprehension of information provided in postprocedural behaviors.

g. Patient satisfaction surveys

h. Postprocedure contacts

(1) Surveys

(2) Telephone contact

(3) Other contacts

11. Use feedback to improve the process for the future.

VII. DOCUMENTATION OF TEACHING PROCESS

A. Provides a legal record that the teaching occurred

1. Include actual information and skills taught.

2. Teaching strategies used

3. Time framework and content for each class

4. Teaching outcomes and methods of evaluation

B. Provides a record for referral and review with the patient at a later date (e.g., follow-up phone contact)

C. Did the patient respond to the education?

D. Documentation components

1. Patient and family learning needs

2. Readiness to learn and learning style

3. Learning objectives

4. Information taught

5. Teaching methods (e.g., brochures, models, video, demonstration)

6. Patient and family response to teaching

7. How learning outcomes were determined

8. Need for additional teaching

9. Resources provided

E. Were the tools and methods used appropriate?

F. Were there any barriers to assessing, planning, and delivering the education?

G. Were the evaluation and analysis objective?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Aldridge, M.D., Writing and designing readable patient education materials, Nephrol Nurs J 31 (4) ( 2004) 373–377.

2. Bastable, S.B., Nurse as educator: Principles of teaching and learning. ed 3 ( 2008)Jones and Bartlett, Sudbury, MA.

3. Berman, A.J.; Burke, K.; Erb, G.; et al., Fundamentals of nursing: Concepts, process, and practice. ed 6 ( 2000)Prentice Hall Health, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

4. Bernier, M.J., Preoperative teaching received and valued in day surgery setting, AORN J 77 (3) ( 2003) 563–572; 575–578, 581–582.

5. Brownson, K., Education handouts. Are we wasting our time?J Nurses Staff Dev 14 (4) ( 1998) 176–182.

6. Burden, N., Ambulatory surgical nursing. ed 2 ( 2000)WB Saunders, Philadelphia.

7. Canobbio, M.M., Mosby’s handbook of patient teaching. ed 2 ( 2006)Mosby, St Louis.

8. Cutilli, C., Do your patients understand? Providing culturally congruent patient education, Orthop Nurs 25 (3) ( 2006) 218–226.

9. In: (Editor: DeFazio-Quinn, D.) Ambulatory surgical nursing core curriculum ( 1999)WB Saunders, Philadelphia.

10. Doak, C.C.; Doak, L.G.; Root, J.H., Teaching patients with low literacy skills. ed 2 ( 1996)Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia.

11. Engel, J.K., Mosby’s pocket guide to pediatric assessment. ed 5 ( 2006)Mosby, St Louis.

12. Habel, M., Getting your message across patient teaching, part 3, Nurs Spectr ( 2005); Available at:www.patienteducationupdate.com/2006–04–01/article3.asp; Accessed March 9, 2009.

13. Jarvis, C., Physical examination and health assessment. ed 5 ( 2008)WB Saunders, Philadelphia.

14. The Joint Commission, 2009 Comprehensive accreditation manual for hospitals: The official handbook. ( 2007)Joint Commission Resources, Oak Brook, IL.

15. The Joint Commission, Comprehensive accreditation manual for ambulatory care (CAMAC). ( 2009)The Joint Commission, Oakbrook Terrace, IL.

16. Kutner, M.; Greenberg, E.; Jin, Y.; et al., Literacy in everyday life: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. ( 2007)U.S Department of Education. National Center for Education Statistics, Washington D.C.; Available at:www.nces.ed.gov/pubs2007/2007480.pdf; Accessed: April 30, 2008.

17. Litwack, K., Core curriculum for perianesthesia nursing practice. ed 4 ( 1999)WB Saunders, Philadelphia.

18. London, F., Moving beyond teaching checklists, Patient Education Update Newsletter ( 3) ( 2005); Fall.

19. Redman, B.K., The practice of patient education. ed 10 ( 2007)Mosby, St Louis.

20. White, S., Assessing the nation’s health literacy: Key concepts and findings of the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL). ( 2008)American Medical Association Foundation, Chicago.

21. Winslow, E.H., Patient education materials, Am J Nurs 101 (10) ( 2001) 33–39.

22. Wong, D.L.; Whaley, L.F.; Wilson, D.; et al., Whaley & Wong’s nursing care of infants and children. ed 6 ( 1999)Mosby, St Louis.