CHAPTER 3. Moral theory and the ethical practice of nursing

L earning objectives

▪ Explain moral justification.

▪ Discuss critically the importance of moral justification to moral decision-making and action.

▪ Outline the relationship between moral justification and moral theory.

▪ Define ethical principlism.

▪ Discuss critically how the moral principles of autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence and justice might be used to guide decision-making in nursing and health care contexts.

▪ Discuss critically a moral rights theory of ethics and its application to nursing.

▪ Discuss critically virtue ethics and its particular significance to nursing ethics.

▪ Distinguish between deontological and teleological ethics.

▪ Differentiate between a moral right and a moral duty.

▪ Discuss critically the limitations and weaknesses of contemporary moral theory.

I ntroduction

When encountering an ethical problem during the course of their work nurses are confronted by at least three basic questions:

In seeking answers to these questions, it would be natural for a nurse to incline toward and draw on his or her own personal values, beliefs, professional knowledge and life experience. Whether this would be sufficient to provide the moral warranties or ‘moral authorisations’ being sought is another matter, however. Deciding the ‘morally right’ thing to do in a situation and taking moral action accordingly is rarely a straightforward process. Among other things it requires a broadly informed, systematic, and deeply experienced approach to thinking about the issues at stake and how best to resolve them. This, in turn, requires ‘mastery’ and ‘not just surface competence’ of relevant ethical concepts and principles as well as ‘the skill to navigate them when they tangle together in concrete situations’ (Little 2001: 35).

Most people have strong beliefs and opinions about the world. No matter how sincerely held, however, beliefs and opinions can sometimes be mistaken. For example, there was a period in history when people sincerely believed that the world was square and that if they sailed to the edge of it they would drop off. Although a sincere belief, the view that the world was square was obviously mistaken, as explorers and scientists later proved. People now hold very different beliefs about the shape and geology of the world and it is conceivable that these too may be challenged and changed in the future.

Most people also have strong beliefs and opinions about what constitutes ‘right’ (good) and ‘wrong’ (bad) conduct. Moral beliefs, like other kinds of beliefs, can be mistaken, however, as centuries of moral inquiry have shown. Indeed, the philosophic literature is full of examples demonstrating convincingly (and giving good reasons for accepting) that some moral decisions and actions are clearly better than others (e.g. acts of compassion are better than acts of cruelty), and that some moral beliefs and theories seem manifestly ‘wrong’ and ought to be rejected (e.g. women lack moral capacity, black people have no moral worth, gay and transgendered people are moral deviants, Nazis had a moral obligation to rid the German nation of its ‘Jewish disease’, and so on).

It is because moral beliefs and opinions can be misguided, misinformed and mistaken — and because people can make mistakes in their moral judgments — that those at the forefront of moral decision-making must provide strong ‘warranties’ (good reasons) for their decisions and actions. It is not acceptable for a person to claim that his/her point of view is more worthy and more moral than another’s (is ‘right’) just because it is his/her point of view. For instance, I cannot claim that my point of view counts more or is more ‘right’ than your point of view just because it is my point of view. Much more is required, namely, there must be a sound justification for holding the point of view that is put forward. I must put forward good reasons why reasonable thinking and ‘right minded’ people should accept the point of view I am advancing. The question that arises here is: What constitutes a ‘sound justification’?

In the discussion to follow, attention will be given to clarifying the nature and importance of justification to moral decision-making and the role of ethical theory (in particular, ethical principlism, moral rights theory and virtue ethics) in providing justification and warranties (moral reasons) for our moral decisions and actions in the workplace.

M oral justification

Moral conflict and disagreement occurs frequently in health care contexts. This is not surprising given the ‘value ladenness’ of the health care practices that occur in health care domains. And given the complexity of the values that operate in health care domains, sometimes the choices we make will be ‘problematic’ insofar as they may express moral values, beliefs and evaluations that are not shared by others or which others do not agree with.

When experiencing situations involving moral disagreement and conflict, it is tempting to rely on our own ordinary moral experience and personal preferences to sustain the point of view we are advocating. As mentioned previously, however, sometimes our own ‘ordinary moral experience’ and personal preferences may not be reliable or worthy action guides because, as Kopelman (1995: 117) warns us, these can result from ‘prejudice, self-interest or ignorance’. In light of this, we need to look elsewhere to strengthen the warranties of (in short, to justify) our moral choices and actions. Moral theory (which has as its focus showing why something is moral in addition to showing that it is moral) is commonly regarded as the definitive source from which such warranties (justifications) can be reliably sought.

Justifying a moral decision or action involves providing the strongest moral reasons behind them. According to Beauchamp and Childress (1994: 13), ‘the reasons that we finally accept, express the conditions under which we believe some course of action is morally justified’. This account is not, however, free of difficulties. As Beauchamp and Childress (p 385) later point out, ‘Not all reasons are good reasons, and not all good reasons are sufficient for justification.’ For instance, a majority public opinion supporting the legalisation of euthanasia may constitute a good reason for decriminalising euthanasia yet stop short of providing a sufficient reason for doing so. For example, other ‘good and sufficient’ reasons might be put forward demonstrating why public opinion is not relevant or adequate to justifying legalised euthanasia, such as: majority opinion tells us only that a certain class of people hold a point of view, not whether that point of view is morally right (euthanasia could still be morally wrong despite a majority view to the contrary); public opinion is notoriously fickle and hence unreliable as a moral action guide — what is deemed ‘right’ by the majority today, could equally be deemed ‘wrong’ tomorrow, (violating the standards of consistency and coherency otherwise expected in the case of sound moral decision-making). Decision-makers thus need to not only provide ‘strong reasons’ for their decisions and actions, but to also distinguish:

a reason’s relevance to a moral judgment from its final adequacy for that judgment, [and also] to distinguish an attempted justification from a successful justification.

(Beauchamp & Childress 2001: 385, emphasis original)

Here, relevance (from the Latin relev aֿre to lighten, to relieve) can be measured by the extent to which the reason (belief) has direct bearing on and makes a material difference to the evaluation made as part of the process aimed at making moral judgments and choices/decisions. Adequacy (from the Lain adaequare to equalise, from ad-to + aequus Equal) can, in turn, be measured by the extent to which it fulfils a need or requirement (in this instance to provide sufficient grounds for belief or action) without being outstanding or abundant. An attempt is simply to ‘make an effort’; to succeed is ‘to accomplish’.

The notion of moral justification is not, however, without difficulties. One reason for this is that there exist a number of different accounts of what constitutes a plausible model of moral justification, and even of how a given or ‘agreed’ model of justification might be interpreted and applied (Beauchamp & Childress 2001; Kopelman 1995; Bauman 1993; Dancy 1993; Nielsen 1989). Some even suggest, controversially, that there can be no adequate model of justification since there is always room to question the grounds that are put forward as ‘good reasons’ supporting a particular act or judgment (see, e.g. Hughes 1995; Johnston 1989).

The problem of moral justification has long been recognised as a crucial one in moral philosophy. As Kai Nielsen reflects (1989: 53):

In ordinary non-philosophical moments, we sometimes wonder how (if at all) a deeply felt moral conviction can be justified. And, in our philosophical moments, we sometimes wonder if any moral judgments ever are in principle justified. Surely, we can find all sorts of reasons for taking one course of action rather than another. We find reasons readily enough for the appraisal we make of types of action and attitudes. We frequently make judgments about the moral code of our own culture as well as those of other cultures. But how do we decide if the reasons we offer for these appraisals are good reasons? And, what is the ground for our decision that some reasons are good reasons and others are not? When (if at all) can we say that these grounds are sufficient for our moral decisions? [emphasis original]

Beauchamp and Childress (2001) suggest three possible answers to these questions, namely, that we can appeal to either: (1) moral rules, principles and theories; (2) lived experience and case examples of individual personal judgments; or (3) a synthesis of both these (theoretical and experiential) approaches. They conclude that of the three approaches, the one that is the most plausible and warranted is the synthesised (or a ‘coherentist’) approach. This approach, unlike the other approaches, involves a strong synergy between theory and practice, with each informing the other and neither being immune to revision. They explain that in everyday moral reasoning, ‘we effortlessly blend appeals to principles, rules, rights, virtues, passions, analogies, paradigms, narratives and parables’ and that ‘we should be able to do the same’ in bioethics (p 408).

This issue will be explored more fully in Chapter 5, Moral problems and moral decision-making in nursing and health care contexts.

T heoretical perspectives informing ethical practice

Western moral philosophy has given rise to many different and sometimes competing theoretical perspectives or viewpoints on the nature and justification of moral conduct. Having some knowledge and understanding of these different perspectives is crucial not just to enhancing our understanding of the complex nature of moral problems and the controversies and perplexities to which they so often give rise, but also to enhancing our abilities to provide satisfactory solutions to the moral problems we encounter in our everyday lives. Unfortunately it is beyond the scope of this book to give an in-depth account of the many ethical theories that have been and remain influential in Western moral philosophical thought (see Chapter 4 of the third edition of this work [Johnstone 1999a]). There are, however, three theoretical frameworks that warrant attention here, namely, those that involve respectively (and sometimes interdependently) an appeal to:

1. ethical principles ( ethical principlism)

2. moral rights ( moral rights theory)

3. moral virtues ( virtue ethics).

These three approaches have emerged as having the most currency and credibility in contemporary health care contexts. Reasons for this include:

▪ they have largely emerged from and been refined by practice

▪ they are able to be readily and meaningfully applied to and in practice

▪ they are amendable to being revised and refined in order to be more responsive to the lived realities of everyday practice.

E thical principlism

One of the most popular theoretical perspectives used today when considering ethical issues in health care is the perspective called ‘ethical principlism’. Ethical principlism is the view that ethical decision-making and problem solving is best undertaken by appealing to sound moral principles. The principles most commonly used are those of: autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence and justice. These principles are generally accepted as providing sound moral reasons for taking moral action.

Although not free of difficulties, ethical principlism has become increasingly accepted as a reliable and practical framework for identifying and resolving moral problems in health care contexts (Benjamin 2001; Little 2001). Since ethical principlism has gained much currency in contemporary discussions on ethical issues in health care (largely because of the influential work on the topic by Beauchamp & Childress [2001]), it is important that nurses have some knowledge and understanding of this approach.

What are ethical principles?

Ethical principles are general standards of conduct that make up an ethical system. To say that a principle is ‘ethical’ or ‘moral’ is merely to assert that it is a behaviour guide which ‘entails particular imperatives’ (Harrison 1954: 115). In this instance the imperatives involve specification (in the form of prescriptions and proscriptions) that some type of action or conduct is either prohibited, required or permitted in certain circumstances (Solomon 1978: 408). By this view, an action or decision is generally considered morally right or good when it accords with a given relevant moral principle, and morally wrong or bad when it does not. To illustrate how this works, consider the action of making a measurement using a ruler. If the line you have drawn measures the desired length of, say, 12 cm — as measured against your ruler — you would judge the length as ‘correct’. If, however, the line you have drawn is only 10 cm long — not the desired 12 cm — you would judge the length to be ‘incorrect’. By analogy, principles also function like rulers, insofar as they provide a standard against which something (in this case, actions) can be measured. For example, if an action fails to ‘measure up’ to the ultimate standards set by a given principle, we would judge the action to be ‘incorrect’ or, more specifically, morally wrong. If, however, an action fully measures up to the ultimate standards set by a given principle, we would judge the action to be ‘correct’ or morally right. The next question is: What are these moral principles against which actions can be measured?

Moral principles commonly used in discussions on ethical issues in nursing and health care include the principles of autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence and justice. It is to examining the content, prescriptive force and application of these principles that this discussion now turns.

Autonomy

The term ‘autonomy’ comes from the Greek autos (meaning ‘self’) and nomos (meaning ‘rule’, ‘governance’ or ‘law’). When autonomy is used as a concept in moral discourse, what is commonly being referred to is a person’s ability to make or to exercise self-determining choice — literally, to be ‘self-governing’. Included here is the additional notion of ‘respect for persons’; that is, of treating or respecting persons as ends in themselves, as dignified and autonomous choosers, and not as the mere means (objects or tools) to the ends of others (Kant 1972; Benn 1971). The principle of autonomy, however, is a little different, and is eloquently formulated by Beauchamp and Walters (1982: 27) as follows:

Insofar as an autonomous agent’s actions do not infringe on the autonomous actions of others, that person should be free to perform whatever action he or she wishes (presumably even if it involves considerable risk to himself or herself and even if others consider the action to be foolish). [emphasis added]

What this basically means is that people should be free to choose and entitled to act on their preferences provided their decisions and actions do not stand to violate, or impinge on, the significant moral interests of others.

Both the concept and the principle of autonomy have important implications for nursing practice. For example, if autonomy is to be taken seriously by nurses, nursing practice must truly respect patients as dignified human beings capable of deciding what is to count as being in their own best interests — even if what they decide is considered by others (including nurses) to be ‘foolish’. In short, nurses must allow patients to participate in decision-making concerning their care. Given this, it soon becomes clear that the whole practice of ‘negotiated patient goals’ and ‘negotiated patient care’ as advocated by contemporary nursing philosophy has its roots in the moral principle of autonomy, and the derived duty to respect persons as autonomous moral choosers. It is not derived merely from a concept of ‘acceptable professional nursing practice’.

In application, the principle of autonomy would judge as being morally objectionable and wrong any act which unjustly prevents autonomous persons from deciding what is to count as being in their own best interests. The kinds of act which might come in for criticism here include, for example:

▪ treating patients without their consent

▪ treating patients without giving them all the relevant information necessary for making an informed and intelligent choice

▪ withholding information from patients when they have expressed a considered choice to receive it

▪ forcing information upon patients when they have expressed a considered choice not to receive it

▪ forcing nurses to act against their reasoned moral judgments or conscience.

It should be noted, however, that while the moral principle of autonomy is very helpful in guiding ethically just practices in health care contexts, it is not entirely unproblematic. Indeed, its uncritical and culturally inappropriate application in some contexts may, in fact, inadvertently cause rather than prevent significant moral harms to patients, for reasons which are considered in Chapter 4.

Non-maleficence

The term ‘non-maleficence’ comes from the Latin-derived maleficent — from maleficus, (meaning ‘wicked’, ‘prone to evil’), from malum (meaning ‘evil’), and male (meaning ‘ill’). As a moral principle, non-maleficence (literally ‘refuse evil’), prescribes ‘above all, do no harm’ which entails a stringent obligation not to injure or harm others. This principle is sometimes equated with the moral principle of ‘beneficence’ (considered below under a separate subheading) which prescribes ‘above all, do good’. Trying to conflate these two obviously distinct principles under one principle is, however, misleading. As Beauchamp and Childress (2001: 114) explain, not only are these two principles obviously distinct (for instance, our obligation not to kill someone does seem qualitatively and quantitatively different from our obligation to rescue someone from a life-threatening situation), but it is important to distinguish between them so as not to obscure other important distinctions which might be made in ordinary moral discourse. One instance in which ‘other important distinctions might need to be made’ is in the case of where both principles might apply to a given situation, but where the strength of the respective moral imperatives of each may nevertheless differ significantly and thus might prescribe quite different courses of action. As Beauchamp and Childress (p 114) point out:

Obligations not to harm others are sometimes more stringent than obligations to help them, but obligations of beneficence are also sometimes more stringent than obligations of non-maleficence.

‘Stringentness’ thus stands as an important distinction that might be obscured if the principles of non-maleficence and beneficence were conflated into one single principle. Beauchamp and Childress (2001: 115) conclude, however, that generally ‘obligations of non-maleficence are more stringent than obligations of beneficence’, and, in some cases, may even override beneficence particularly in instances where beneficent acts, paradoxically, are not morally defensible (e.g. depriving one’s family of food for a week and failing to pay the rent [thereby increasing the risk of eviction] because of donating the household’s weekly budget to charity).

Applied in nursing contexts, the principle of non-maleficence would provide justification for condemning any act which unjustly injures a person or causes them to suffer an otherwise avoidable harm (such as in the first case scenarios presented in Chapters 1 and 2 of this book, involving nurses who mistreated elderly people in their care).

Before continuing, some commentary is warranted on the notion of ‘harm’ and how it might be interpreted (given that it is open to a variety of interpretations). For the purposes of this discussion, harm may be taken to involve the invasion, violation, thwarting or ‘setting back’ of a person’s significant welfare interests to the detriment of that person’s wellbeing (Feinberg 1984: 34; Beauchamp & Childress 2001: 116–17). Interests, in this instance, are taken to mean ‘a miscellaneous collection, consist[ing] of all those things in which one has a stake’ together with the ‘harmonious advancement’ of those interests (Feinberg 1984: 34). Interests are morally significant since they are fundamentally linked to human wellbeing; specifically, they stand as a fundamental requisite (although, granted, not the whole) of human wellbeing (Feinberg 1984: 37). Wellbeing, in turn, can include interests in:

continuance for a foreseeable interval of one’s life, and the interests in one’s own physical health and vigour, the integrity and normal functioning of one’s body, the absence of absorbing pain and suffering or grotesque disfigurement, minimal intellectual acuity, emotional stability, the absence of groundless anxieties and resentments, the capacity to engage normally in social intercourse and to enjoy and maintain friendships, at least minimal income and financial security, a tolerable social and physical environment, and a certain amount of freedom from interference and coercion.

(Feinberg 1984: 37)

The test for whether a person’s interests and wellbeing have been violated, ‘set back’, thwarted or invaded rests on ‘whether that interest is in a worse condition than it would otherwise have been in had the invasion not occurred at all’ (Feinberg 1984: 34). For instance, if a person (e.g. a patient) is left psychogenically distressed (e.g. emotionally distressed, anxious, depressed and even suicidal) or in a state of needless physical pain and/or disability as a result of his/her experiences (e.g. as a patient in a given health care setting) our reflective commonsense tells us that this person’s interests have been violated and the person him/herself ‘harmed’. As the American philosopher Joel Feinberg (1984) further explains, the violation of a person’s welfare interests renders that person ‘very seriously harmed indeed’ since ‘their ultimate aspirations are defeated too’.

Beneficence

The term ‘beneficence’ comes from the Latin beneficus, from bene (meaning ‘well’ or ‘good’) and facere (meaning ‘to do’). The principle of beneficence prescribes ‘above all, do good’; in practice, it entails a positive obligation to literally ‘act for the benefit of others’ viz contribute to the welfare and wellbeing of others (Beauchamp & Childress 2001: 166). Acts of beneficence can include such virtuous actions as: care, compassion, empathy, sympathy, altruism, kindness, mercy, love, friendship and charity. It is recognised, however, that bestowing benefits on others is not always without cost to the benefactor. Thus there are some limits to the principle; that is, it is not ‘free standing’ and its application can be appropriately constrained by other moral (for example, utilitarian) considerations. To put this another way, we are not obliged to act beneficently towards others when doing so could result in our own significant moral interests being seriously harmed or compromised in some way.

Although the notion of ‘obligatory beneficence’ remains a controversial one in moral philosophy (for instance, it is popularly accepted that we are not ‘morally required to benefit persons on all occasions, even if we are in a position to do so’), there are nevertheless a number of conditions under which a person can indeed be said to have an obligation of beneficence and that this obligation might, sometimes, be overriding. These conditions, devised by Beauchamp and Childress (2001: 171), are as follows:

a person X has a determinate obligation of beneficence toward person Y if and only if each of the following conditions is satisfied (assuming X is aware of the relevant facts):

1. Y is at risk of significant loss of or damage to life or health or some other major interest.

2. X’s action is needed (singly or in concert with others) to prevent this loss or damage.

3. X’s action (singly or in concert with others) has a high probability of preventing it.

4. X’s action would not present significant risks, costs, or burdens to X.

5. The benefit that Y expected to gain outweighs any harms, costs, or burdens that X is likely to incur.

They go on to suggest that it is only when these conditions are satisfied that a person’s ‘general duty of beneficence’ becomes a ‘specific duty of beneficence’ towards another given individual.

The principle stands to have an interesting and useful application in nursing practice. Consider the following case (personal communication; names have been changed).

Mrs Jones, a Jehovah’s Witness, is admitted to an intensive care unit in the final stages of life, suffering from advanced hepatitis B and severe liver failure. She has a slow internal haemorrhage and is only semiconscious. Before her alteration in consciousness she had given her doctors a written statement specifically requesting that she not be given a blood transfusion under any circumstances. Upon her arrival in the unit, however, the attending doctor prescribes a unit of blood and requests that it be given immediately. Mrs Jones’ husband and children are all present and, upon overhearing the doctor’s request, become very upset. Mr Jones approaches the doctor and asks that his wife not be given the blood transfusion. He reminds the doctor that Mrs Jones has made explicit her wish not to have a blood transfusion under any circumstances. Nurse Smith, the registered nurse caring for Mrs Jones, hears the discussion and has to make a decision whether or not to intervene on her patient’s behalf. In making her decision, Nurse Smith might appeal to the principle of beneficence in the following manner:

1. Mrs Jones, a Jehovah’s Witness in the final stages of life, is at risk of suffering a significant loss (a violation of her spiritual values and beliefs) if she is given the medically prescribed blood transfusion

2. action by Nurse Smith, the attending nurse, is needed to prevent Mrs Jones from experiencing the loss in question

3. Nurse Smith’s action of refusing to administer the prescribed transfusion would probably prevent Mrs Jones’ loss

4. Nurse Smith’s action will not present a significant risk to her (i.e. she will not lose her job)

5. the benefits gained by Mrs Jones outweigh any harms Nurse Smith is likely to suffer (given that Nurse Smith autonomously chooses to uphold Mrs Jones’ interests, and does not stand to suffer any morally significant consequences of her actions).

In this particular case the nurse refused to give the transfusion which had been prescribed. When the doctor insisted that it be given, the nurse pointed out that the transfusion would probably be of no clinical benefit to Mrs Jones, as she was clearly in the end stages of her disease — to put it bluntly, ‘she was dying’. Nurse Smith then suggested to the doctor that perhaps he would prefer to administer the transfusion himself. Interestingly, the doctor declined this invitation, and the transfusion was not given. Mrs Jones died a short while later, without having to experience a needless violation of her expressed wishes, values and beliefs.

In summary, by this principle, any act which fails to address an imbalance of harms over benefits where this can be done without sacrificing a benefactor’s own significant moral interests, warrants judgment as being morally unacceptable.

Justice

The principle of justice (its nature and content), unlike the principles above, is not so amenable to definition or quantification. As a point of interest, questions concerning what justice is and what its origins are have occupied the minds of philosophers for nearly 3000 years, and to this day remain the subject of intensive philosophical debate (MacIntyre 1988; Nussbaum 2006; Powers & Faden 2006; Solomon & Murphy 1990). Significantly, the end result of this great philosophical debate has not been the development of a singular and refined universal theory of justice, but the development of a range of rival theories of justice (MacIntyre 1988). Different conceptions of justice (from the Latin justus meaning ‘righteous’) have included: justice as revenge (retributive justice — e.g. ‘an eye for an eye’); justice as mercy (Christian ethics); justice as harmony in the soul and harmony in the state (Pythagorean ethics, 600 BC–1 AD); justice as equity (impartiality and fairness); justice as equality (‘equals must be treated equally, and unequals unequally’); justice as an equal distribution of benefits and burdens (distributive justice and redistributive justice); justice as what is deserved (‘each according to one’s merit or worth’); and justice as love (Beauchamp & Childress 2001; MacIntyre 1985, 1988; Nussbaum 2006; Outka 1972; Rawls 1971; Powers & Faden 2006; Nozick 2007; Singer 1991; Solomon & Murphy 1990; Waithe 1987). More recently justice has been conceptualised as reconciliation and reparation (restorative justice), a key purpose of which is to ‘restore broken relationships’ (Tutu 1999; see also Johnstone G 2002; Sullivan & Tift 2006). Arguably one of the most novel conceptions of justice is that of justice as a basic human need that, like other basic human needs (notably those famously depicted in Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs), is critical to producing the necessary conditions of life (Taylor 2003, 2006).

Given these different conceptions of justice, the problem arises of what, if any, conception of justice nurses should adopt? While it is beyond the scope of this book to answer this question in depth, there is nevertheless room to advocate at least three senses of justice which nurses might find helpful: (1) justice as fairness and impartiality (equity justice); (2) justice as the equal distribution of benefits and burdens (distributive and redistributive justice); and justice as reconciliation and reparation (restorative justice). It is these three senses of justice which will now be considered.

Justice as fairness and impartiality (equity)

Justice as fairness finds interpretation in terms of ‘what is owed or due’. Here, it can be said that ‘one acts justly toward a person when that person has given what is due or owed’; an injustice, by this view, would involve:

a wrongful act or omission that denies people benefits to which they have a right, or distributes benefits unfairly.

(Beauchamp & Childress 2001: 226)

If a person deserved something, justice is done when that person receives that particular something. Here, the ‘something’ may be either positive (a reward) or negative (a punishment). This view relies very heavily on an ‘intuitive’ sense of justice. For example, we may ‘feel’ it is unjust to punish or censure someone for a harm they did not cause, or not to punish someone for a harm they did deliberately cause. Likewise we may feel that it is unjust to reward someone for an accomplishment to which they contributed nothing, and yet not reward someone who contributed a great deal.

We do not need to look far in nursing practice to find sobering examples of where the principle of justice as fairness has been violated. Consider cases where nurses have been subjected to severe legal and professional censure, held solely responsible and have even lost their jobs because of making an honest mistake (Johnstone 1994; Johnstone & Kanitsaki 2006a).

Other examples involve cases where nurses have gained promotion or have secured employment on the basis of their claiming credit for the work of either their peers or their subordinates. At the other end of the continuum, some nurses have been denied promotion or employment because their superior has ignored, or refused for whatever reasons to recognise significant professional achievements the nurse applicant has in fact made.

How, then, might we make choices on this view of justice? One possible approach which has received widespread attention is that discussed by the contemporary American philosopher John Rawls. He argues, for example, that if parties are to exercise truly just or fair choices, they must choose from a hypothetically ‘neutral’ position, or from a position of what he describes as being ‘behind the veil of ignorance’ (Rawls 1971: 12). From such a position he argues (p 12):

no-one knows his [sic] place in society, his [sic] class position or social status, nor does anyone know his [sic] fortune in the distribution of natural assets and abilities, his [sic] intelligence, strength, and the like … [T]his ensures that no-one is advantaged or disadvantaged in the choice of principles by the outcome of natural chance or the contingency of social circumstances. Since all are similarly situated and no-one is able to design principles to favour his [sic] particular condition, the principles of justice are the result of a fair agreement or bargain.

While Rawls’ view is problematic (it is open to serious question whether, in fact, all choosers are or could ever be ‘similarly situated’, as he assumes), it has nevertheless been extremely persuasive. A key reason for this persuasiveness relates to broader philosophical demands that are inherent in Western bioethics and which emphasise, among other things, that moral choice and judgment should be exercised from a position of impartiality and objectivity. However, whether in fact human beings are ever capable of exercising truly impartial and ‘objective’ choices — indeed, of choosing from behind that veil of ignorance — remains a matter of some controversy. Some critics also argue that Rawls’ theory is too narrow, pointing out that it has failed to take a more responsive approach to social cooperation and the needs of people who are disabled, ‘not equal’, disadvantaged, and who belong to other non-human species (see Nussbaum 2006). One reason for this is that it pays too much attention to patterns of distribution, rather than to the ‘procedural issues of participation, deliberations and decision-making’ (Young 2007: 600). Moreover, Rawls’ theory fails to take into account that what is important is not just the distribution of benefits and burdens per se, but how various distributions came about (Nozick 2007).

Despite its weaknesses, Rawls’ justice theory provides a useful catalyst for thinking about the notion of fairness and how it might be used in real-life situations. It also alerts us to some of the potential difficulties of trying to determine and apply an uncontentious view of justice.

Justice as an equal distribution of benefits and burdens

A second (and related) sense in which justice can be used is that pertaining to ‘distributive justice’; that is, an equal distribution of benefits and harms. By this view, all people are required to bear an equal share of their society’s benefits and burdens. Such a view admits that all persons must have equal claims to liberty and opportunity, but in a way that is compatible with the claims of others. As well as this, there must be equal access (and opportunity to gain access) to positions of authority and power, and there must be an equal distribution of wealth and income (a point often missed in conservative constructions of justice as equity — such as outlined above). The only morally acceptable exception to this would be if an unequal distribution would work to everyone’s advantage (Beauchamp & Childress 2001: 226), or where an unequal distribution of benefits would be necessary so as to ‘maximise the minimum level of primary goods in order to protect vital interests in potentially damaging or disastrous contexts’ (p 226). Simply put, inequalities in distributing benefits and primary goods are ‘just’ as long as this results in the least well-off (i.e. those who are already disadvantaged unfairly) achieving a decent minimum level of wellbeing (i.e. being advantaged by the benefits which have been conferred unequally).

As with the fairness sense of justice discussed earlier, we do not need to look far to find sobering examples in nursing where the principle of distributive justice has been violated. In many cases, nurses have had to (and continue to) bear unequal and intolerable burdens on account of certain inequities in the distribution of scarce health care resources. For example, historically nurses have had to endure poor and unsafe working conditions with a maximum of responsibility and a minimum of financial or personal reward (Johnstone 1994, 2002a).

In considering the fairness and the distributive senses of justice, it is instructive to note that both uphold two common minimal principles: formal equality (‘equals must be treated equally, and unequals must be treated unequally’); and a mixture of autonomy and beneficence (‘we all ought to bear certain burdens, usually of a minimal sort, for the common good’) (Beauchamp & Childress 1989: 256–306).

In calculating the balance or distribution of harms and benefits, notions of comparative and non-comparative justice are also used. Justice is ‘comparative’ when what a person deserves can be determined only by balancing the competing claims of others against the person’s own claims (Beauchamp & Childress 2001: 226–37). For example, whether a nurse qualifies for a job or a promotion will depend largely on the competing claims of the other applicants. If the other applicants are more qualified and more experienced, it seems reasonable to hold that they are more ‘deserving’ of the position being offered. Justice is ‘non-comparative’, on the other hand, when ‘desert is judged by standards independent of the claims of others’ (pp 227–30). For example, a nurse who is guilty of breaching acceptable professional standards of conduct deserves to be censured, or even deregistered, if the breach of conduct warrants such an action; a nurse who is innocent of professional misconduct, however, does not deserve to be censured or deregistered.

Justice as reconciliation and reparation

A third (and less well known) sense in which justice can be used is in a reconciliation and reparative sense, otherwise referred to as ‘restorative justice’. In contradistinction to retributive justice (the primary aim of which is to assign blame and punish offenders), restorative justice has as its primary aim:

healing rather than hurting, moral learning, community participation and community caring, respectful dialogue, forgiveness, responsibility, apology and making amends

(Braithwaite 1999: 6)

Historically, small societies have often used means other than retribution to ‘resolve conflict and restore harmony’ (Maxwell & Morris 2006: 72). Thus, instead of using punishment to redress a wrong, processes for promoting healing and restoration have been emphasised (Maxwell & Morris 2006; Johnstone G 2002; Sullivan & Tifft 2005, 2006). This approach has, however, also worked in large nations. A poignant example of this can be found in the extraordinary case of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which commenced in May 1996 following the collapse of the apartheid regime in that country. Based on the Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act, 1995 (available for viewing at: www.doj.gov.za/trc/), the TRC was conducted in the spirit of ubuntu, an African jurisprudence principle which emphasises ‘the healing of breaches, the redressing of imbalances, the restoration of broken relationships’ (Tutu 1999: 51). Although severely criticised by some for its ‘religious components’ (notably the promulgation of the assumptions that ‘truth is a precursor to forgiveness’ and ‘forgiveness is necessary for healing’) and the demonstrable negative impact it had on the mental health of some individuals and families (Swartz & Drennan 2000), the TRC is nonetheless credited with being an instrument of national healing. It has also been credited with providing a ‘third way’ for redressing the past and to enable the country to move forward and not descend into mayhem and civil war, as has happened so often in other countries where people have suffered years of oppression and brutality (Tutu 1999).

Over the past two decades, restorative values have also been translated and applied in practice as a form of ‘therapeutic jurisprudence’ in the cultural contexts of New Zealand, Canada, the United States (US) and Australia. Although primarily advanced as an Indigenous Justice Initiative aimed at assisting in the rehabilitation of young offenders from Indigenous communities and ‘restoring’ them to their communities (see Braithwaite 1999; Maxwell & Morris 2006; Johnstone G 2002; Sullivan & Tifft 2005, 2006), restorative justice has also been applied in broader contexts. Some notable examples include its use to improve compliance with regulatory standards in health care contexts (see Makkai & Braithwaite 1994; Freckelton & Flynn 2004), and to rehabilitate and restore community and population health (Ashworth 2002; Freudenberg 2001). As the negative health consequences of individual as well as institutional injustices become more apparent (see Herndon 1992; Taylor 2003, 2006), the need of a ‘third way’ to resolve conflict and restore harmony — to ‘find out the truth, heal breaches, redress imbalances, restore broken relationships, and rehabilitate both victims and perpetrators injured by an offence without resorting to a system of retributive justice’ (Johnstone G 2002) — will become more pressing, and the possible remedies offered by restorative justice compelling both as a ‘moral measure’ and a moral course of action.

Moral rules

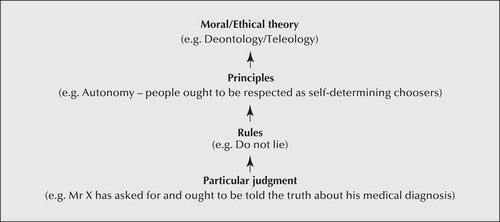

Moral principles are not the only entities that make up an ethical system or ethical framework for guiding conduct. Moral rules also have a place in guiding and ‘warranting’ ethical conduct. Like moral principles, moral rules function by specifying that some type of action or conduct is either prohibited, required or permitted (Solomon 1978: 408–9). What distinguishes a moral rule from a moral principle in certain contexts is its structure and nature. Moral principles, for instance, tend to be regarded as providing the content of morality, and the bases or the ‘parent’ forms from which general moral truths (insofar as these can be determined) are derived. In application, moral principles incline more towards a general focus. Consider, for example, the broad moral principle of ‘autonomy’. In general, the principle demands that persons should be respected as autonomous choosers, capable of judging what is in their own best interests. As such, rational persons should be free to act as they wish provided their actions do not violate the moral interests of others.

Moral rules, on the other hand, stand as being merely derivative of moral principles and theories and, in application, are much more particular in their focus. Although it is difficult to draw a firm distinction between moral rules and moral principles, it is generally recognised that moral rules have different force, sanctioning power, conditions of existence, scope of application and level of concreteness from moral principles (Solomon 1978). An example of a moral rule would be the demand, say, to ‘always tell the truth’ or ‘never tell a lie’. Thus, if a patient asks an attending health care professional a question concerning a diagnosis and proposed treatment, the health care professional could be said to be obliged to give the information the patient has requested. The apparent ‘obligation’ here finds its force not just from the moral rule ‘always tell the truth’, but from the moral principle of autonomy which demands that rational people be respected as autonomous choosers, and be given the information required to make an informed and intelligent choice.

Another example can be found in a set of rules that prescribe such things as ‘do not kill others’, ‘do not cause pain and suffering to others’, ‘do not affect detrimentally the physical and mental health of others’, and so forth. The apparent obligations here find their force not just from the rules stated, but from the moral principle non-maleficence which prescribes ‘do no harm’.

In order for a particular moral rule (or set of moral rules) to be justified, it must be fully derived from and reducible to established parent principles of morality.

In summary, moral rules derive from moral principles, and as such have only prima-facie force (i.e. they can be overridden by stronger moral claims). Given their prima-facie nature, moral rules cannot override the moral principles from which they have been derived. To accept that they could would be to suggest, somewhat paradoxically, that derived rules could meaningfully conflict with parent principles — which, of course, is absurd. The relationship between particular moral judgments, moral rules, moral principles and moral theories is shown in Figure 3.1.

|

| Figure 3.1

(Source: Adapted from Beauchamp T & Childress J [1994] Principles of biomedical ethics, 4th edn. Oxford University Press, New York: 15)

|

The question of moral rules is an important one for nurses, particularly as it relates to the broader issue of professional codes of conduct, an issue that will become clearer in the following chapters.

Problems with ethical principles

In considering ethical principlism it is important to be aware of a number of difficulties that can arise when appealing to the ethical principles described. For example, problems commonly associated with ethical principlism include:

▪ deciding correctly which principles apply in a given situation (e.g. ‘Is it the principle of autonomy or beneficence that applies in this case, or both?’)

▪ deciding correctly the relative weights of given principles (e.g. ‘Which principle has overriding consideration in this case — the principle of autonomy or the principle of non-maleficence?’)

▪ balancing the demands of different principles in situations where their respective though equally weighted demands might conflict (e.g. ‘How can I uphold the principle of autonomy without, at the same time, violating the principle of justice which has an equal bearing in this case?’)

▪ deciding whether ethical principles apply at all (e.g. ‘This is a matter to be resolved by kindness and care — by being virtuous — not by appealing to ethical principles per se’)

▪ resolving disagreement with others regarding either of the above (e.g. ‘I feel strongly that respecting the patient’s autonomy in this case means withholding the information about his diagnosis as he has requested, but others in the team do not agree and are going to tell him insisting he must be told so that he can make informed choices about his future treatment.’).

The issue of moral uncertainty, moral dilemmas and moral disagreements in regard to the selection, interpretation and application of ethical principles will be explored further in the chapters to follow.

M oral rights theory

Of the moral theories that have been appealed to in the contemporary literature on ethics, a ‘rights’ view of ethics is probably the one that has the most currency among professional and lay communities alike. Certainly most people have a sense that they have ‘rights’ and that their rights, whatever these may be, ‘ought to be respected’. Important questions to ask are: What are moral rights? Who has them? and To what extent are others obliged to respect them?

Moral rights theory has emerged as an extremely influential theoretical perspective across the globe. Evidence of this can be found in the vast array of contexts in which moral rights discourse has been used. For example, we see moral rights discourse in: position statements and bills of clients’/patients’ rights; professional codes of ethics and conduct (e.g. the International Council of Nurses’ Code for Nurses and supporting position statements); statutory authorities (e.g. the various Australian state and territory Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commissions); government inquiries (e.g. the Report of the National Inquiry into the Human Rights of People with Mental Illness by Burdekin et al 1993); and in international covenants, conventions and treaties (e.g. the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948; the ratification of The International Bill of Human Rights [United Nations 1978]). There is also an abundance of literature on the subject. If nurses are to participate effectively in discourses on moral rights, it is essential that they have some understanding of the theoretical underpinnings of a moral (and human) rights perspective on ethics. It is to providing a brief examination of moral rights theory that this section will now turn.

Moral rights

Moral rights (to be distinguished here from human rights, legal rights, institutional rights, civil rights, etc) generally entail claims about some special entitlement or interest which ought, for moral reasons, to be protected. The kinds of interests for which protection might be sought include, for example, life, freedom, happiness, privacy, self-determination, fair treatment and bodily integrity. The language used in asserting rights typically involves expressions such as: ‘I have a right to …’, ‘It’s your right to …’, ‘They have a right to …’, and so on. A rights claim is generally accepted as a sound moral reason for taking moral action.

There is no single thesis of moral rights. The following is a brief overview of some of the better known classical and contemporary theories concerning the existence of moral rights and the conditions under which they can be validly claimed.

Moral rights based on natural law and divine command

Natural rights theory argues that certain entitlements are simply ‘built into’ the universe like the laws of gravity, and as such are neither the products of human invention nor the constructs of other moral theories (Martin & Nickel 1980). A variation of this thesis is that natural rights have been divinely ordained for all human beings. From both these points of view, since the laws of nature and the ordinances of God apply equally to all human beings, it follows that all human beings — young and old; male, female, transgender and intergendered (e.g. haemophrodites); homosexual, heterosexual and bisexual; abled and disabled; black, white and coloured — unconditionally have natural rights.

Objections to this account of moral rights derive from those raised against a theological account of morality generally. For example, if it were shown that God did not exist, or that natural law did not exist, this account of moral rights would immediately collapse because its very foundation would be pulled out from underneath it. Another objection rests on the problem that natural rights essentially defy scientific verification.

Moral rights based on common humanity

Another popular natural rights thesis is that all human beings have rights simply by virtue of being ‘human’ and ‘equal’. What is critical to this thesis is the notion that ‘being human’ is something over which we have no control; that is, we cannot choose to be either human or not human (Martin & Nickel 1980). In this sense, then, we can be said to enjoy a ‘common humanity’, a notion which Leah Curtin (1986) explores in her treatment of advocacy. This view of rights is vulnerable to the objection that not all human rights are moral rights per se. The human right to education, which is dependent on the availability of educational resources, is an example of a human right which is not a moral right per se.

Another more serious problem is that given the recent advancements made in the field of genetic engineering, ‘being human’ may indeed be something over which we have control in the near future. Human genes have already been cloned onto animals (e.g. pigs and fish); it is not far-fetched to imagine that scientists will succeed (if they have not already done so) in cloning animal genes onto humans. Persons with a genetic makeup comprising both human and non-human genes could be said to be not ‘fully human’, at least, not in a ‘speciesist’ sense. Were someone to be not ‘fully human’, their claim to moral rights on the basis of a common humanity would be cast in doubt. Conversely, if a non-human nonetheless has human genes and/or human characteristics (e.g. chimpanzees that are capable of performing abstractions), they too might hold claim to what are otherwise upheld as being exclusively ‘human rights’ (see also Dershowitz 2004: 143).

Moral rights based on rationality

A Kantian thesis (i.e. a thesis based on the philosophical views of the German philosopher Immanuel Kant) of natural rights holds rationality as being the sole basis upon which a right’s claim can be made. In other words, only those people who are capable of rational, autonomous thought are entitled to claim moral rights. One disturbing consequence of this thesis is that any human being (or non-human being, for that matter) who is unable to reason is not regarded as having moral status. Such a view clearly excludes infants, brain-dead and intellectually disabled persons, and others with severe organic brain states corrosive of their ‘personhood’ from having a just claim to moral rights. It might be tempting to dismiss this view as being merely an intellectual one, of interest only to moral philosophers. There is ample evidence, however, that this view is influential and enjoys considerable currency in the ‘real world’ of human affairs. (The most notable examples here can be found in the use of ‘brain-dead’ persons, fetuses and live-born anencephalics as organ donors [Meinke 1989; Bioethics Committee, Canadian Paediatric Society 2005; Fost 2004; Siminoff 2004].)

Moral rights based on interests

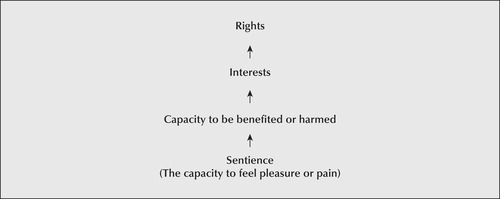

The North American philosopher Joel Feinberg offers quite a different theory of moral rights. He argues that, in order for an entity to be able to claim rights meaningfully, that entity must have interests (Feinberg 1979). To have interests, the entity must be capable of being either benefited or harmed. In order to be either benefited or harmed, one must be able to experience pleasure and pain. In short, unless one has sentience one cannot have interests, and thus cannot be either benefited or harmed, and therefore cannot make claims. This theory of moral rights can be expressed diagrammatically as shown in Figure 3.2.

|

| Figure 3.2 |

It can be seen that by this view it would be nonsense to assert, for example, that a rock has rights. Why? Because a rock does not have sentience and therefore cannot, strictly speaking, be benefited or harmed, and thus cannot meaningfully be said to have interests, and hence rights. Those who value rocks (e.g. conservationists, geologists, rock collectors) might be benefited or harmed by what happens to a rock, but it is not meaningful, philosophically speaking, to assert that a rock per se has rights. In contrast, any entity which can be shown to have sentience (that is, the capacity to experience pleasure or suffer pain) would, by this view, be entitled to be respected as having rights. Given this, it is clear that we can, for example, assert meaningfully that beings such as dolphins, puppies, kittens, horses, people who cannot think or reason or express their wishes because of an incapacitating brain injury or other debilitating brain disease, and babies have moral rights.

Like Bentham, the founding father of utilitarianism (to be discussed later in this chapter), Feinberg sees the capacity to suffer, not reason, as the ultimate basis upon which a person’s interest claims become the focus of moral action.

One shortcoming of this view is that individuals must be able to represent their own interests. Feinberg (1979: 595) argues that, if individuals cannot represent their own interests, they have no more rights than ‘redwood trees and rosebushes’. Unhappily, the ‘human vegetable’, it seems, is no better off under an interests-based thesis of moral rights than it is under a thesis based on reason.

Feinberg does not, however, offer an adequate account of why entities must be able to ‘represent their own interests’. As contemporary theorists have recently shown, human beings (especially those who are vulnerable) do not necessarily ‘have to be capable of making claims, or have the capacity to function as a moral agent in order to have rights’ (Dyck 2005: 116). Feinberg also fails to account for why others (who are capable of making sound judgments about the moral interests of vulnerable persons and acting in a way to protect those interests) cannot speak for individuals, families and groups when they are unable or incapable of speaking on their own behalf. Moreover, there is considerable scope to suggest that an interests-based thesis of moral rights justifies and, in some contexts, even commands surrogate representation — particularly in the case of human beings who are vulnerable and unable (because of their age, impairment of cognitive function, physical confinement, political oppression, emotional distress, and so forth) to ‘speak for themselves’ and/or effectively represent their own best interests (Hoffmaster 2006; Kottow 2003, 2004; Purdy 2004).

Moral rights based on human experiences of grievous wrongs

Not all agree with the above theories of the origins of rights. Dershowitz, for example, a leading legal scholar from Harvard University, argues that human rights do not derive from God, nature, logic, or otherwise, but from ‘particular human experiences’ — notably of the ‘worst injustices’ and ‘most grievous wrongs’ and the ongoing quest by reasonable people to prevent their reoccurrence and to ‘righting the wrongs’ that have occurred (Dershowitz 2004: 81–2). With reference to some of the world’s most potent historical examples of ‘worst injustices’ and ‘most grievous wrongs’ (genocide and slavery being two standout examples), Dershowitz (p 90) contends:

Where the majority does justice to the minority, there is little need for rights. But where injustice prevails, rights become essential. Wrongs provoke rights, as our checkered history confirms.

Drawing on this observation, and advancing a thesis of ‘nurtural rights’ (to be distinguished from ‘natural rights’), he concludes that human rights thus have their origin in human wrongs, and that, in essence, a theory of rights is ipso facto also a theory of wrongs (Dershowitz 2005: 81).

An important question to arise here is: How are we to know what are ‘most grievous wrongs’? Dershowitz suggests, first, that ‘if wrongs were not wrongs’, then it is reasonable to ask why their perpetrators go to such lengths to hide or disguise them — pointing out that ‘even Hitler and his henchmen tried to hide their genocidal actions behind euphemisms and evasive rhetoric’ (Dershowitz 2005: 81). Second, there is likely to be more agreement than not among reasonable people as to what constitute ‘most grievous wrongs’. On this point Dershowitz (p 83) argues:

Reasonable people will always disagree about the nature of the perfect good, but there will be less disagreement about the evils that experience has taught us to prevent.

Finally, and arguably most propitiously, is the burgeoning of rights themselves immediately after a most grievous wrong has been acknowledged, as numerous examples in history can readily demonstrate (the formulation and ratification of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights being just one example) (Dershowitz 2005: 94–5). Importantly, rights can also ‘quickly contract’ in the aftermath of wrongs ‘believed to be caused by excessive rights’ claims (p 95) — an issue that is explored further under the subheading ‘Rights and responsibilities’ in this chapter).

Dershowitz (2005) concludes that ‘righting wrongs’ is an ongoing process that will see rights in a constant state of flux as they adapt and counter each new injustice. Accordingly, those who believe in rights must ‘take their case to the people’ and must engage in the positive project of constantly proving that ‘rights work’, that ‘they are necessary to prevent wrongs, and that they are worth the price we sometimes pay for them’ (p 232).

Different types of rights

When speaking of moral rights, it is important to distinguish three different types which can be claimed, notably: inalienable, absolute and prima-facie rights.

Inalienable rights

An inalienable right is one which cannot be transferred under any circumstances. For example, if we accept the right to life as being an inalienable right, we are committed to accepting that it cannot be transferred to someone else or for some other cause under any circumstances. According to this view, sacrificing one’s life either in suicide, martyrdom, or in an act of supreme altruism (e.g. a mother sacrificing her life for her child) would be deemed as morally wrong. Of course, we may ask the question whether the right to life is an inalienable right.

Absolute rights

An absolute right, by contrast, is a right which cannot be overridden under any circumstances. For example, if we take the right to life as being absolute, we would be bound to respect it whatever the cost. By this view, any wilful taking of human life, whether through war, self-defence, abortion, capital punishment, or any other act, would be morally wrong. Here the question arises whether the right to life really is an absolute right.

Prima-facie rights

A prima-facie (from the Latin primus, meaning ‘first’, and facies, meaning ‘face’) right is a right which may be overridden by stronger moral claims. For example, a patient’s right to privacy may be overridden by the right to life in a cardiac arrest situation where the patient’s body is exposed during the resuscitation procedure. In such an emergency, it would be misguided for an ethicist to insist that the patient’s right to privacy should take priority in the situation at hand.

Some argue against the notion of prima-facie rights by saying that if a right can be overridden it does not exist. Against such a criticism, Martin and Nickel (1980: 172–4) comment:

to describe a right as Prima Facie is to say something about its weight but not about its scope or conditions of possession … Overridence depends on whether the case of conflict is central to the values that the right serves to protect or whether it is a marginal case and thus can be expected in all cases without great loss to those values.

M aking rights claims

Having a right usually entails that another has a corresponding duty to respect that right. As Feinberg (1978: 1508) explains, when people assert their moral rights, they assert a kind of ‘moral power’ over us which we feel constrained to respect. Where claims have a special convincing force they have a coercive effect on our judgments, which in turn make us feel driven to both acknowledge and support the interest claims being made as being genuine rights claims.

Rights which entail a corresponding duty are typically referred to as ‘claims rights’. These rights can be either positive or negative, and can entail either a positive or a negative rights claim. Positive rights claims generally entail a correlative duty to act or to do, in contrast with a negative rights claim which generally entails a correlative duty to omit or to refrain (Feinberg 1978: 1509). For example, if a patient claims a right not to be harmed, this claim imposes a negative duty on an attending nurse to refrain from acts which may cause harm. On the other hand, if a patient claims a right to be benefited in some way, such as by having an intolerable pain state relieved, this imposes a duty on an attending nurse to perform the positive act of promptly administering an effective analgesic. If a person’s rights claims are not upheld, or are infringed or violated in some way, that person generally feels wronged or feels a serious injustice has been done. In a rights view of ethics, if someone claims a right this is generally regarded as providing a ‘moral reason’ (a warranty) for taking moral action.

R ights and responsibilities

Any discussion on moral rights would not be complete without also considering the responsibilities that rights holders have when choosing to claim or exercise their rights in given contexts. The need to take into account the moral responsibilities associated with rights claims has become especially pressing in recent years on account of the rise-and-rise of ‘unrestricted isolated individualism’ (also called ‘rampant individualism’) in English-speaking democracies of the developed world (e.g. the United States (US), the United Kingdom (UK), Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and so forth) (see Dyck 2005; Glendon 1991; Nussbaum 2006; Young 1990). Paradoxically, this rampant individualism — sometimes decried in terms of ‘people having all rights and no responsibilities’ — is threatening to weaken and even nullify the very system of rights that, up until now, has served the significant moral interests of individuals, groups and even whole communities whose wellbeing has been at serious risk and even substantially harmed because of oppression, exploitation, violence and other harmful human behaviours perpetrated by more powerful and dominant others.

In recent years there has been increasing recognition (and criticism) of the tendency in classical moral rights theory to fail to take into account the fundamental connection between rights and responsibilities and, in particular, the responsibility that rights’ holders have to exercise their rights in a just and responsible manner. This stance has given rise to a ‘new’ view of rights, notably, as a just expectation, that is, a state of being characterised by ties of mutually expected responsibilities to one another, as individuals and as members of groups and institutions (Dyck 2005: 117).

Referring to the classic works of the 19th century British philosopher John Stuart Mill, Dyck (2005) contends that since rights are fundamentally rooted in justice, then rights must themselves be exercised ‘justly’ (p 115). Quoting Mill (‘Justice implies something which is not only right to do, and wrong not to do, but which some persons can claim from us as his [sic] moral right’), Dyck explains that, since justice is itself a ‘moral responsibility’, in the context of rights claims this imposes an obligation on people:

(1) to honour rights that justifiably claim one or another of our various moral responsibilities, and (2) to claim from other individuals, groups, or institutions only those actions for which they can be held morally responsible (Dyck 2005: 115).

Dyck goes on to caution that irresponsible rights claims stand to not only violate the principle of justice but, in doing so, weakens the claims themselves. Irresponsible claims thus stand as ‘violations’ (i.e. of ‘just expectations’ that bona fide rights claims will be exercised responsibly) that, in turn, threaten to tear (and, as racial violence and civil war can readily attest, has torn) the moral fabric of communities apart. Dyck further cautions that unless individuals, groups and social institutions claiming rights ‘are willing and able to act responsibly’ — by which he means ‘act to maintain the moral bonds of community’ — then those rights ‘are not and cannot be actualised’ (Dyck 2005: 114). In other words, the failure to exercise rights claims justly and responsibly could nullify the rights claims altogether, something that could have serious consequences at both a practical and theoretical level. In contrast, exercising given rights claims justly and responsibly actually strengthens the rights claims being made. Moreover, by recognising the responsibilities that come with rights, claimants help to form and maintain what Dyck (p 132) calls the ‘inhibitions against causing evil’, notably, ‘destroying individuals and human relations’ and the human wellbeing that is otherwise so dependent on these relations being maintained in a manner that is just and nurturing.

Problems with rights claims

In discussing rights it is important to keep in mind at least six central problems that can arise when dealing with rights claims. First, rights and interests can seriously compete and conflict with one another. For example, a patient’s right to life could seriously compete or conflict with another patient’s right to life in a situation involving scarce medical resources; or a nurse’s conscientious refusal to assist with an abortion procedure could conflict with a patient’s right to have an abortion and to receive care following the procedure. In such instances there may be no easy solution to the conflict of interests at hand.

Second, it may be difficult to establish the extent to which a person’s rights claim entails a correlative duty. For example, if someone claims a right to life, who or what has the corresponding duty to respond to that claim? Does it fall to the health professional, or to family, friends, the hospital, the state or another entity? There may be no satisfactory answer to this question.

Third, there may be disagreement about which entities have rights. For example, some might argue that brain-dead people, anencephalic babies, the intellectually impaired and babies do not have moral rights, while others might argue that they do. Again there may be no satisfactory resolution to this type of disagreement.

Fourth, it may be very difficult to try and satisfy the rights claims of all people equally. For instance, if there is a genuine lack of resources, it may be impossible to satisfy all rights claims. Once again, we are left, unhappily, with an unresolved moral problem.

Fifth, it may be very difficult to determine what counts as a responsible and irresponsible rights claim and the conditions under which an irresponsible rights claimant might forfeit his or her entitlements (have their rights claims nullified).

Sixth, and more seriously, is the controversial claim that moral rights theory is not a complete theory at all, but only ‘a piece of a more general account of what makes a claim valid [and justified]’ — a ‘partial framework’ as it were (Beauchamp & Childress 2001: 361). By this view, rather than being a comprehensive theory, a moral rights perspective is at best only an account of ‘minimal and enforceable rules that communities and individuals must observe in their treatment of persons’ (Beauchamp & Childress 1994: 76, emphasis added).

On account of these and other difficulties (not least, the inherent adversarial nature of rights claims and entitlements), some have sought to avoid a moral rights perspective altogether, or at least to ‘replace the language of rights’ (Beauchamp & Childress 2001: 362). (For example, when referring to people’s moral entitlements, instead of using ‘rights’ language, some writers use such terms as ‘interests’, ‘welfare’, ‘wellbeing’, and so on.) Others, however, defend the use of rights language despite the theoretical weaknesses of a moral rights perspective. Beauchamp & Childress, for example, contend that (p 362):

No part of the moral vocabulary has done more to protect the legitimate interests of citizens in political states than the language of rights. Predictably, injustice and inhumane treatment occur most frequently in states that fail to recognise human rights in their political rhetoric and documents. As much as any part of moral discourse, rights language crosses international boundaries and enters into treaties, international law, and statements by international agencies and associations. Rights thereby become acknowledged as international standards for the treatment of persons.

Others have taken a similar stance adding that rights discourse has a ‘high reputation’ and, for all its weaknesses, continues to enjoy ‘pervasive popularity’ in the world at large (Campbell 2006: 1, 5). Reasons for the success of rights discourse have been identified by Campbell as involving the strong association it has with the language of:

▪ imperatives (‘To have a right is to have something that overrides other considerations in both moral and legal discourse’)

▪ individualism (‘A society based on rights is believed to manifest and affirm the dignity of each and every human life as something that is deserving of the highest respect’)

▪ remedies (‘Rights are not associated with simply aspiring to do what is good or desirable but demand restraint, redress and rectification of wrong done in violation of rights’)

▪ security (‘Having rights enables us not only to enjoy certain benefits but to have knowledge that they are ours “by right” and cannot therefore be taken away at the whim of others’)

▪ universality (‘The generality of rights offers protection to individuals against arbitrary treatment, a feature which is most evident when universal rights are ascribed to all persons irrespective of the race, religion, class or gender’).

(Campbell 2006: 1, 5)

The issue of moral rights is an important one for nurses — particularly as the issue relates to patients’ rights and the patients’ rights movement, and also to the relationship between health and human rights that has been receiving increasing attention in recent years. As these are substantial issues in their own, they are considered separately in Chapter 6 of this book (see also Realizing Rights: the Ethical Globalization Initiative, which can be viewed at http://www.realizingrights.org/).

V irtue ethics

In recent times there has been a resurgence of virtue theory in ethics and a re-examination of the importance of ‘characterological excellence’ as an ingredient of authentic moral conduct (Hursthouse 2007; van Hooft 2006). Virtue ethics holds a particular relevance for nursing since virtuous conduct is intricately linked to therapeutic healing behaviours and the promotion of human wellbeing.

Virtue ethics (also known as character ethics) has an impressive history dating back to the ancient philosophical and theological texts of both Western and non-Western cultures (Beauchamp & Childress 2001; Hursthouse 2007; Kruschwitz & Roberts 1987; Pellegrino 1995). As Pellegrino (p 254) writes, ‘Virtue is the most ancient, durable, and ubiquitous concept in the history of ethical theory.’

Despite its durability, virtue theory has nonetheless been in various stages of decline over the past several centuries — particularly within the field of Western moral philosophy. This decline can be traced to the rise of scientism. By the late 17th and 18th centuries, for instance, the ‘Enlightenment project of finding a rational justification for morality’ saw moralists look away from the law of God ‘to actual, observable human nature for a justification of traditional moral norms’ (MacIntyre, Krushwitz & Roberts 1987: 12–13). Although virtue ethics has retained its currency in some fields, for example, the medical profession up until as late as the 1970s (Pellegrino 1995: 264), and the nursing profession up until the present time (Armstrong 2006; Begley 2006; McKie & Swinton 2000), its importance to and in moral philosophy has long been lost, having been seriously neglected by philosophers preoccupied with turning ethics into a science.

Significantly, since the 1980s, there has been a revival in virtue-based theories of ethics (Hursthouse 2007; Pellegrino 1995; Pence 1984; van Hooft 2006). This revival (which has included both religious and non-religious approaches to virtue theory) has been driven by an increasing dissatisfaction and frustration among some philosophers with the otherwise narrow, abstract, impersonal and at times oversimplified approach of traditional theories of ethics, and the need to find an alternative approach that is more reflective of and responsive to the complexities of the moral life (Pellegrino 1995; Pence 1991; van Hooft 2006). Of particular concern has been the questionable neglect within mainstream moral philosophy of considerations relating to the moral character of moral agents (persons who engage in moral actions). One aspect of this concern is expressed eloquently by Pence (1991: 256), who, commenting on what he sees as ‘a common defect in non-virtue theories’, points out:

On the theories of duty or principle, it is theoretically possible that a person could, robot-like, obey every moral rule and lead the perfectly moral life. In this scenario, one would be like a perfectly programmed computer (perhaps such people do exist, and are products of perfect moral educations).

The idea that persons could function as ‘moral robots’ is both disturbing and unsatisfactory to virtue theorists, and, it might be added, to others who feel at least an intuitive unease about the prospect of morality being merely a matter of following a set of rules. We do seem to think, as Clouser (1995: 231) reminds us, that morality ‘also encourages us to act in ways that go beyond what is required’ — beyond a robot-like obedience to rules.

There does seem to be something ‘missing’ in the traditional picture of ‘the moral life’. For virtue theorists, this ‘something’ is character. As Pence (1991: 256) writes:

we need to know much more about the outer shell of behaviour to make such [moral] judgments, i.e. we need to know what kind of person is involved, how the person thinks of other people, how he or she thinks of his or her own character, how the person feels about past actions, and also how the person feels about actions not done.

Furthermore, there is a sense in which virtue theory is inevitable. As Pellegrino (1995: 254) points out: