History

Comments

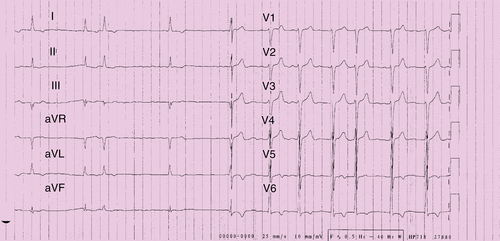

FIGURE 28-1

Current Medications

Comments

Current Symptoms

Physical Examination

Comments

Laboratory Data

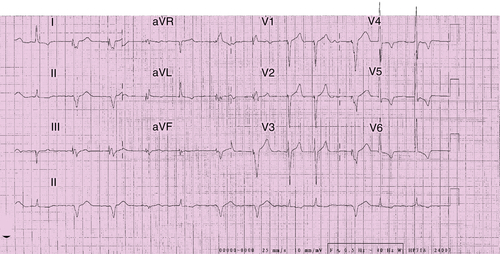

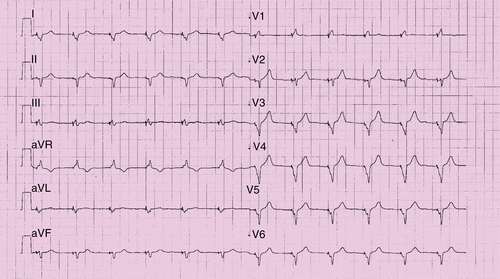

Electrocardiogram

Findings

Comments

FIGURE 28-2

FIGURE 28-3

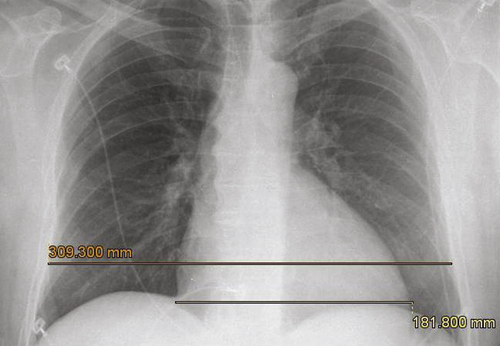

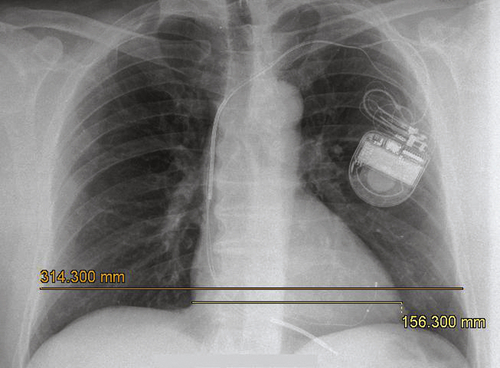

Chest Radiograph

Comments

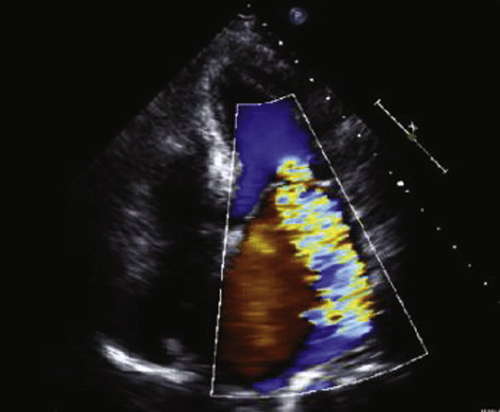

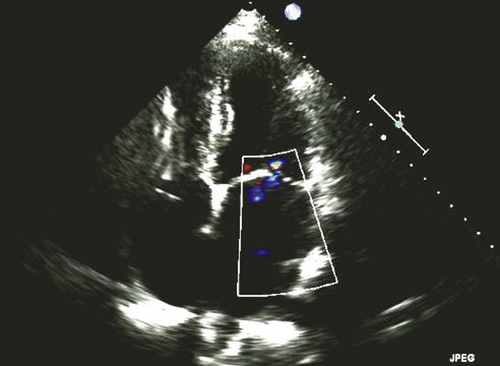

Echocardiogram

Comments

FIGURE 28-4

FIGURE 28-5

FIGURE 28-6

FIGURE 28-7

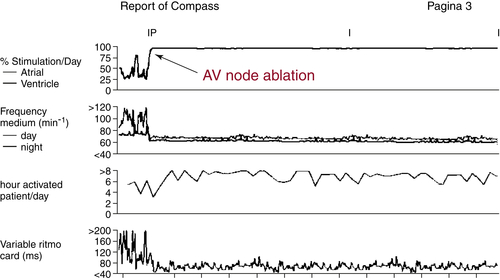

Physiologic Tracings

Findings

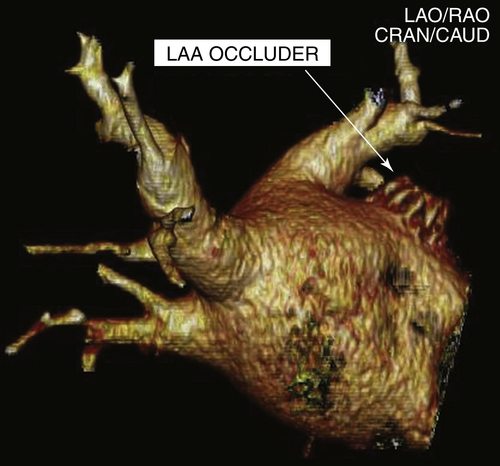

Computed Tomography

Comments

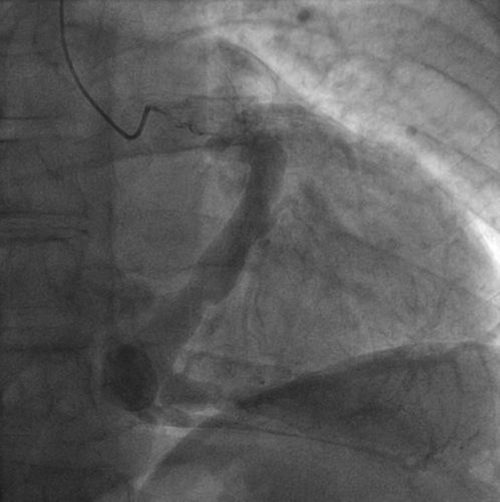

Catheterization

Findings

Focused Clinical Questions and Discussion Points

Question

Discussion

Question

FIGURE 28-8

FIGURE 28-9

FIGURE 28-10

FIGURE 28-11

Discussion

Question

Discussion

Final Diagnosis

Plan of Action

Intervention

Outcome

Selected References

1. Gasparini M., Auricchio A., Regoli F. et al. Four-year efficacy of cardiac resynchronization therapy on exercise tolerance and disease progression: the importance of performing atrioventricular junction ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:734–743.

2. Gasparini M., Auricchio A., Metra M. et al. Long-term survival in patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy: the importance of performing atrio-ventricular junction ablation in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1644–1652.

3. Kaszala K., Ellenbogen K.A. Role of cardiac resynchronization therapy and atrioventricular junction ablation in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2344–2346.

4. Brignole M., Botto G., Mont L. et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients undergoing atrioventricular junction ablation for permanent atrial fibrillation: a randomized trial. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2420–2429.

5. Koplan B.A., Kaplan A.J., Weiner S. et al. Heart failure decompensation and all-cause mortality in relation to percent biventricular pacing in patients with heart failure: is a goal of 100% biventricular pacing necessary? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:355–360.

6. Hayes D.L., Boehmer J.P., Day J.D. et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy and the relationship of percent biventricular pacing to symptoms and survival. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1469–1475.

7. Ganesan A.N., Brooks A.G., Roberts-Thomson K.C. et al. Role of AV nodal ablation in cardiac resynchronization in patients with coexistent atrial fibrillation and heart failure: a systematic review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:719–726.