Thoracentesis (Assist)

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Thoracentesis is performed with insertion of a needle or a catheter into the pleural space, which allows for removal of pleural fluid.

• Pleural effusions are defined as the accumulation of fluid in the pleural space that exceeds 10 to 20 mL and results from the overproduction of fluid or disruption in fluid reabsorption.1

• Thoracentesis is not used to verify the presence of pleural effusion. Diagnosis of pleural effusion is made via clinical examination, patient symptoms, and diagnostic techniques. A number of techniques can demonstrate pleural effusion with varying levels of sensitivity. Percussion requires a minimum of 300 to 400 mL for identification of a pleural effusion, whereas standard chest radiography requires 200 to 300 mL. Lateral decubitus radiographs can recognize smaller fluid amounts and highlight whether present fluid is free flowing. Ultrasound scan, computed tomography (CT) scan, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology can detect 100 mL of fluid with 100% sensitivity.1 Therefore, initial diagnosis of pleural effusion should use imaging techniques such as chest radiographs, ultrasound scan, CT scan, or MRI, combined with patient symptoms and clinical examination findings.

• Diagnostic thoracentesis is indicated for differential diagnosis for patients with pleural effusion of unknown etiology. A diagnostic thoracentesis may be repeated if initial results fail to yield a diagnosis.

• Therapeutic thoracentesis is indicated to relieve the symptoms (e.g., dyspnea, cough, hypoxemia, or chest pain) caused by a pleural effusion.

• Exudative effusions indicate a local etiology (e.g., pulmonary embolus, infection), whereas transudative effusions usually are associated with systemic etiologies (e.g., heart failure).

• Samples of pleural fluid are analyzed and assist in distinguishing between exudative and transudative etiologies of effusion. Results of laboratory tests on pleural fluid alone do not establish a diagnosis; instead, the laboratory results must be correlated with the clinical findings and serum laboratory results.

• Exudative pleural effusions meet one of the following criteria1:

Pleural fluid lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)-to-serum LDH ratio is greater than 0.6 international units/mL.

Pleural fluid lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)-to-serum LDH ratio is greater than 0.6 international units/mL.

Pleural fluid LDH is more than two thirds of the upper limit of normal for serum LDH.

Pleural fluid LDH is more than two thirds of the upper limit of normal for serum LDH.

Pleural fluid protein-to-serum protein ratio is greater than 0.5 g/dL.

Pleural fluid protein-to-serum protein ratio is greater than 0.5 g/dL.

• A transudative pleural effusion is considered when none of the exudative criteria are met.

• Transudative effusions usually are associated with systemic etiologies (e.g., heart failure), whereas exudative effusions indicate a local etiology (e.g., pulmonary embolus, infection, open heart surgery).

• Relative contraindications for thoracentesis include the following:

Patient anatomy that hinders the practitioner from clearly identifying the appropriate landmarks

Patient anatomy that hinders the practitioner from clearly identifying the appropriate landmarks

Patients undergoing anticoagulant therapy or having an uncorrectable coagulation disorder

Patients undergoing anticoagulant therapy or having an uncorrectable coagulation disorder

Patients receiving positive end-expiratory pressure therapy

Patients receiving positive end-expiratory pressure therapy

Patients with splenomegaly, elevated left hemidiaphragm, and left-sided pleural effusion

Patients with splenomegaly, elevated left hemidiaphragm, and left-sided pleural effusion

Patients with only one lung as a result of a previous pneumonectomy

Patients with only one lung as a result of a previous pneumonectomy

• Ultrasound scan–guided thoracentesis is thought to reduce complications, especially when used in the last four patient groups listed in the relative contraindications list.2,3

• Complications commonly associated with thoracentesis include:

EQUIPMENT

Diagnostic Thoracentesis

• Baseline diagnostic study results (i.e., lateral decubitus chest radiograph, ultrasound scan imaging, CT scan, or MRI)

• Completed patient informed consent form

• Functional intravenous access

• Adhesive bandage or adhesive strip

• Intervention medications (opioid, sedative, or hypnotic agents, local anesthetic 1% or 2% lidocaine)

• One small needle (25-gauge, ⅝-inch long)

• 5-mL syringe for local anesthetic

• Three large needles (20-gauge to 22-gauge, 1½ to 2 inches long)

• Pillow or blanket to be placed on side table

• Available: Atropine, oxygen, thoracostomy supplies, advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) equipment

Therapeutic Thoracentesis

The following equipment is needed in addition to equipment for diagnostic thoracentesis:

Additional equipment (to have available depending on patient need) includes the following:

• Two complete blood count (CBC) tubes

• One anaerobic and one aerobic media bottle for culture and sensitivity

Commercially prepackaged thoracentesis kits are available in some institutions.

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the procedure and purpose for thoracentesis, including potential complications, such as pneumothorax, pain at insertion site, cough, infection, hypoxemia, and hypovolemia. Include an explanation of the amount of fluid expected to be withdrawn, duration of time procedure may last, and expectation of and reason for coughing during or after thoracentesis.  Rationale: This communication identifies patient and family knowledge deficits concerning patient condition, procedure, expected benefits, and potential risks and allows time for questions to clarify information and voice concerns. Explanations decrease patient anxiety and enhance cooperation.

Rationale: This communication identifies patient and family knowledge deficits concerning patient condition, procedure, expected benefits, and potential risks and allows time for questions to clarify information and voice concerns. Explanations decrease patient anxiety and enhance cooperation.

• Explain the patient’s role in thoracentesis.  Rationale: This explanation increases patient compliance, facilitates needle and catheter insertion, and enhances fluid removal.

Rationale: This explanation increases patient compliance, facilitates needle and catheter insertion, and enhances fluid removal.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Obtain a history of symptoms, occupational exposure, and medication usage.

• Signs and symptoms of pleural effusion include the following:

Trachea deviated away from the affected side

Trachea deviated away from the affected side

Affected side dull to flat with percussion

Affected side dull to flat with percussion

Absent or decreased breath sounds on the affected side

Absent or decreased breath sounds on the affected side

Cough, weight loss, night sweats, anorexia, and malaise may also occur with pleural infection or malignancy disease.6

Cough, weight loss, night sweats, anorexia, and malaise may also occur with pleural infection or malignancy disease.6

Rationale: Although physical findings may suggest a pleural effusion, other imaging studies confirm its presence.

Rationale: Although physical findings may suggest a pleural effusion, other imaging studies confirm its presence.

• Assess chest radiograph or other imaging findings.  Rationale: If at least half the hemidiaphragm is obliterated on erect anterior-posterior radiograph results, sufficient fluid is in the pleural space for a thoracentesis. Greater than 200 mL of fluid is considered abnormal in erect chest radiograph results. Lateral radiographs show blunting of the costophrenic angle with 50 mL. With a small amount of loculated fluid, however, a lateral decubitus radiograph should be obtained. Lateral decubitus radiographs assist with distinguishing between free-moving fluid and pleural thickening. If the pleural effusion is measured to be greater than 10 mm deep on a lateral decubitus radiograph, a diagnostic thoracentesis can be performed. However, if the pleural effusion is measured to be less than 10 mm in diameter or loculated, ultrasound scan is necessary to distinguish between pleural effusion and pleural lesion. Ultrasound scan–guided thoracentesis may be necessary if a pleural effusion has been confirmed. In the intensive care setting, supine anterior-posterior radiographs are less sensitive in the identification of pleural effusions. In this setting, hazy opacification of one lung field or minor fissure thickening may be the only clues to the presence of a pleural effusion.6

Rationale: If at least half the hemidiaphragm is obliterated on erect anterior-posterior radiograph results, sufficient fluid is in the pleural space for a thoracentesis. Greater than 200 mL of fluid is considered abnormal in erect chest radiograph results. Lateral radiographs show blunting of the costophrenic angle with 50 mL. With a small amount of loculated fluid, however, a lateral decubitus radiograph should be obtained. Lateral decubitus radiographs assist with distinguishing between free-moving fluid and pleural thickening. If the pleural effusion is measured to be greater than 10 mm deep on a lateral decubitus radiograph, a diagnostic thoracentesis can be performed. However, if the pleural effusion is measured to be less than 10 mm in diameter or loculated, ultrasound scan is necessary to distinguish between pleural effusion and pleural lesion. Ultrasound scan–guided thoracentesis may be necessary if a pleural effusion has been confirmed. In the intensive care setting, supine anterior-posterior radiographs are less sensitive in the identification of pleural effusions. In this setting, hazy opacification of one lung field or minor fissure thickening may be the only clues to the presence of a pleural effusion.6

• Assess medical history of pleuritic chest pain, cough, dyspnea, malignancy disease, heart failure, and medication usage.  Rationale: Medical history may provide valuable clues to the cause of a patient’s pleural effusion or presence of hypercoagulable states. Knowledge of medication usage can indicate the need for anticoagulation reversal before an invasive procedure. In addition, an increasing number of medications is noted to contribute to exudative effusions. Common examples include amiodarone, phenytoin, nitrofurantoin, and methotrexate. See www.pneumotox.com for a more comprehensive listing.4,6

Rationale: Medical history may provide valuable clues to the cause of a patient’s pleural effusion or presence of hypercoagulable states. Knowledge of medication usage can indicate the need for anticoagulation reversal before an invasive procedure. In addition, an increasing number of medications is noted to contribute to exudative effusions. Common examples include amiodarone, phenytoin, nitrofurantoin, and methotrexate. See www.pneumotox.com for a more comprehensive listing.4,6

• Assess baseline vital signs, including pulse oximetry.  Rationale: Baseline assessment data provide information about patient status and allow for comparison during and after the procedure.

Rationale: Baseline assessment data provide information about patient status and allow for comparison during and after the procedure.

• Assess recent laboratory results, including the following:

Rationale: These studies help determine whether the patient is at increased risk for bleeding. Generally, an INR of 1.3 or less is acceptable for invasive procedures.

Rationale: These studies help determine whether the patient is at increased risk for bleeding. Generally, an INR of 1.3 or less is acceptable for invasive procedures.

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that the patient understands pre-procedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise and reinforce information.  Rationale: This communication evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

Rationale: This communication evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

• Obtain written informed consent for the procedure.  Rationale: Invasive procedures, unless performed with implied consent in a life-threatening situation, require written consent of the patient or significant other.

Rationale: Invasive procedures, unless performed with implied consent in a life-threatening situation, require written consent of the patient or significant other.

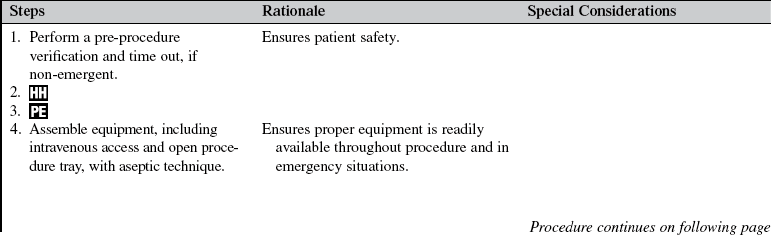

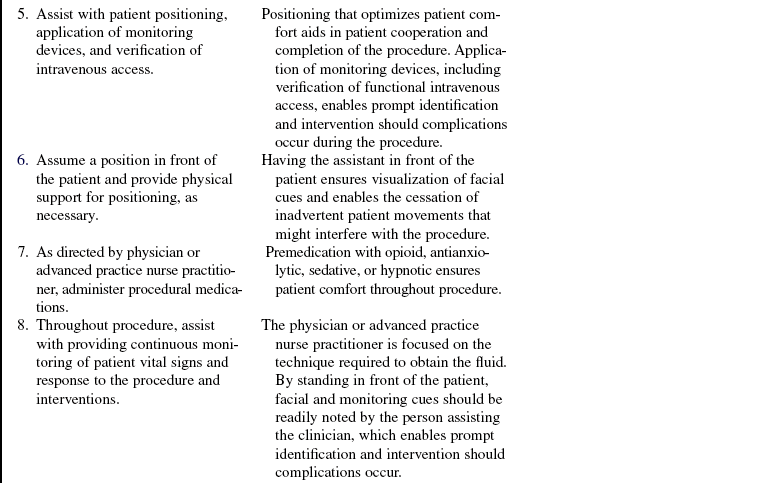

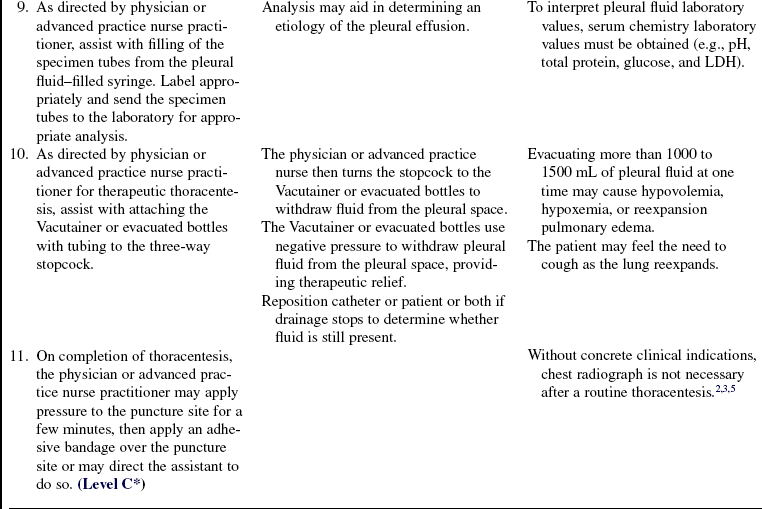

• Position the patient. Several alternative positions may be used, as follows:

If the patient is alert and able, position the patient on the edge of the bed with legs supported and arms resting on a pillow on the elevated bedside table (see Fig. 26-1).

If the patient is alert and able, position the patient on the edge of the bed with legs supported and arms resting on a pillow on the elevated bedside table (see Fig. 26-1).

The patient may sit on a chair backward and rest arms on a pillow on the back of the chair.

The patient may sit on a chair backward and rest arms on a pillow on the back of the chair.

If the patient is unable to sit, position the patient on the unaffected side, with the back near the edge of the bed and the arm on the affected side above the head. Elevate the head of the bed to 30 or 45 degrees, as tolerated.

If the patient is unable to sit, position the patient on the unaffected side, with the back near the edge of the bed and the arm on the affected side above the head. Elevate the head of the bed to 30 or 45 degrees, as tolerated.

Rationale: Positioning enhances ease of withdrawal of pleural fluid.

Rationale: Positioning enhances ease of withdrawal of pleural fluid.

• Have an additional member of the healthcare team positioned in front of the patient.  Rationale: This positioning reassures or comforts the patient and provides additional assistance.

Rationale: This positioning reassures or comforts the patient and provides additional assistance.

• Consider sedation or paralysis.  Rationale: Sedation or paralysis may be necessary to maximize positioning.

Rationale: Sedation or paralysis may be necessary to maximize positioning.

• Have atropine available.  Rationale: Bradycardia, from a vasovagal reflex, is a common occurrence during thoracentesis.

Rationale: Bradycardia, from a vasovagal reflex, is a common occurrence during thoracentesis.

• Initiate pulse oximetry monitoring.  Rationale: Pulse oximetry provides a noninvasive means for monitoring oxygenation and heart rate at the bedside, which allows for prompt recognition and intervention should problems occur.

Rationale: Pulse oximetry provides a noninvasive means for monitoring oxygenation and heart rate at the bedside, which allows for prompt recognition and intervention should problems occur.

References

![]() 1. Barton, E. Thoracentesis. In: Rosen P, Chan T, Vilke G, et al, eds. Atlas of emergency procedures. St Louis: Mosby, 2001.

1. Barton, E. Thoracentesis. In: Rosen P, Chan T, Vilke G, et al, eds. Atlas of emergency procedures. St Louis: Mosby, 2001.

![]() 2. Colt, HG, Brewer, N, Barbur, EB. Evaluation of patient–related and procedure-related factors contributing to -pneumothorax following thoracentesis. Chest. 1999; 116:134–138.

2. Colt, HG, Brewer, N, Barbur, EB. Evaluation of patient–related and procedure-related factors contributing to -pneumothorax following thoracentesis. Chest. 1999; 116:134–138.

![]() 3. Gervais, DA, et al, US-guided thoracentesis. requirement for post procedure chest radiography in patients who receive mechanical ventilation versus patients who breathe spontaneously. Radiology 1997; 204:503–506.

3. Gervais, DA, et al, US-guided thoracentesis. requirement for post procedure chest radiography in patients who receive mechanical ventilation versus patients who breathe spontaneously. Radiology 1997; 204:503–506.

![]() 4. Maskell, NA, Butland, RJA. BTS guidelines for the investigation of a unilateral pleural effusion in adults. Thorax. 2003; 58:ii8.

4. Maskell, NA, Butland, RJA. BTS guidelines for the investigation of a unilateral pleural effusion in adults. Thorax. 2003; 58:ii8.

![]() 5. Peterson, WG, Zimmerman, R. Limited utility of chest radiograph after thoracentesis. Chest. 2000; 117:1038–1042.

5. Peterson, WG, Zimmerman, R. Limited utility of chest radiograph after thoracentesis. Chest. 2000; 117:1038–1042.

6. Rahman, N, Chapman, S, Davies, R, Pleural effusion. a structured approach to care. Br Med Bull. 2005; 72(1):31–47.

Antunes, G, Neville, E, Duffy, J, et al. BTS guidelines for the management of malignant pleural effusions. Thorax. 2003; 58(Suppl 2):ii29–38.

Davies, CWH, Gleeson, FV, Davies, RJO. BTS guidelines for the management of pleural infection. Thorax. 2003; 58:ii18.

Doyle, JJ, et al. Necessity of routine chest roentgenography after thoracentesis. Ann Intern Med. 1996; 124:816–820.

Heffner, JE, Brown, LK, Barbieri, CA. Diagnostic value of tests that discriminate between exudative and transudative -pleural effusions. Chest. 1997; 111:970–980.

Light, RW, et al, Pleural effusion. the diagnostic separation of transudates and exudates. Ann Intern Med 1992; 77:507–513.

Loddenkemper R. Pleural effusions. In: Albert R, Spiro S, Jett J, eds. Clinical respiratory medicine. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2004.

Mayo, PH, Goltz, HR, Tafreshi, M, et al. Safety of ultrasound-guided thoracentesis in patients receiving mechanical -ventilation. Chest. 2004; 125(3):1059–1062.

Quigley, RL. Thoracentesis and chest tube drainage. Crit Care Clin. 1995; 11:111–126.

Thomsen, TW, DeLaPena, J, Stenik, GS, Thoracentesis. Videos in Clinical Medicine. 09; 355(15)-14-2008 e16 (15). http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/video_preview/355/15/e16 [retrieved from accessed].

Wilson, M, Irwin, R. Thoracentesis. Procedures and techniques in intensive care medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincot Williams & Wilkins; 2003.