Administration

Edited by George Jelinek

27.1 Emergency department staffing

Sue Ieraci and Julie Considine

General principles

Patients requiring emergency care have the right to timely care by skilled staff. The aim of staffing an emergency department is ultimately to provide care in an acceptable time according to the patient’s clinical urgency (triage category). Staff working in the emergency department also have the right to safe and manageable working conditions and reasonable job satisfaction.

As the activity of an emergency department fluctuates in both volume and acuity, a threshold level of staffing and resources is required in order to be prepared for likely influxes of patients. In addition, the staffing number and mix needs to take account of the important teaching role of emergency departments.

The precise numbers and designation of medical, nursing, allied health and other staff employed will be determined by the local work practices (what tasks are carried out and by whom). This chapter discusses staffing requirements under the current Australasian model of emergency department work practices. This includes a major supervisory and teaching role for consultants and a significant proportion of specialist trainees and junior medical staff in the medical workforce, with a range of tasks, including venepuncture, test requisitioning and written documentation. In addition, roles are expanding into wider realms, such as toxicology, ultrasound and academic and observation medicine. Nursing roles range from bedside monitoring, physical care and treatment to advanced practice roles, including the initiation of tests and treatment.

Estimating medical workload

Emergency department (ED) case mix and costing studies have sought to measure the medical time commitment for various clinical conditions. Table 27.1.1 describes the approximate average medical time commitment for each of the Australasian Triage Scale categories [1]:

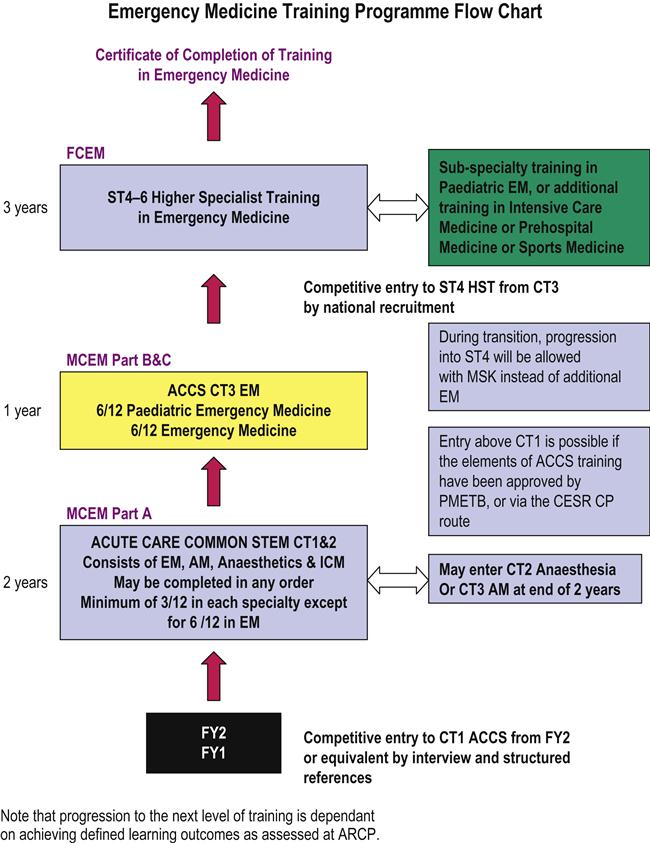

The workforce should be resourced and organized so that patients are treated within the benchmark times for their clinical acuity (triage category). The Australasian College for Emergency Medicine (ACEM) has defined benchmarks for waiting time by triage category (Table 27.1.2) [2].

The workforce should be resourced and organized so that patients are treated within the benchmark times for their clinical acuity (triage category). The Australasian College for Emergency Medicine (ACEM) has defined benchmarks for waiting time by triage category (Table 27.1.2) [2].

Table 27.1.2

Benchmarks for waiting time by triage category

| Category 1 | Category 2 | Category 3 | Category 4 | Category 5 | |

| Treatment acuity | Immediate | Within 10 min | Within 30 min | Within 60 min | Within 120 min |

| Benchmark performance (%) | 98 | 95 | 90 | 90 | 85 |

Table 27.1.1

Australasian Triage Scale categories

| NTS category | Medical time (min) |

| Category 1 | 160 |

| Category 2 | 80 |

| Category 3 | 60 |

| Category 4 | 40 |

| Category 5 | 20 |

Structure of medical staff

The medical workforce of Australasian emergency departments currently includes the following categories:

consultants (specialist emergency physicians), including a medical director

consultants (specialist emergency physicians), including a medical director

registrars (specialist trainees)

registrars (specialist trainees)

senior non-specialist staff: experienced hospital medical officers

senior non-specialist staff: experienced hospital medical officers

The specialist practice of emergency medicine includes non-clinical roles (including departmental management and administration, planning, education, research and medicopolitical activities) as well as clinical roles. The non-clinical workload of an individual department varies with its size and role, the structure of its staffing and the other management systems within the institution. For senior staff, clinical work generally includes coordination of patient flow, bed management and supervision and bedside teaching of junior staff, in addition to direct patient care. Some emergency physicians may have other particular roles, such as retrieval and hyperbaric medicine or toxicology services. The increasing number of academic staff may have major research and teaching commitments.

To cover these roles, the ACEM recommends a minimum of 30% non-clinical time for consultants (more for directors of departments and directors of emergency medicine training) and 15% non-clinical time for registrars.

Throughout Australasia, EDs are experiencing increasing levels of activity. The calculation of medical staff numbers required for a particular department must include not only the extent of consultant cover required, but also the clinical workload and performance, local work practices and the nature of clinical and non-clinical roles. Because of variations in roles and work practices between sites, it is not possible to devise a staffing profile that is universally appropriate. Other recent changes in staffing patterns include employment across a network, increasing part-time work and sessional contract arrangements. Many emergency physicians are diversifying their practice profile to achieve a balanced and sustainable career, combining salaried and contract work, different types of hospitals and part-time work with a range of other interests.

Estimating nursing workload

Australian models for calculating ED nursing workload include the Emergency Care Workload Unit [3] (based on triage category and admission status) and the Victorian Nurse-to-Patient Ratio model [4] (using patient dependencies). Additionally, a minimum skill mix is required to manage the acute and complex workload. In addition to the bedside nursing workload, there are requirements to provide for education and training, patient flow and both clinical and departmental administrative roles. Larger departments require clinical managers on every shift.

Nurse staffing structure

In Australia, there are three levels of nurses registered with the Australian Health Professionals Regulation Agency (AHPRA):

Enrolled nurses work under the supervision of registered nurses and their scope of practice is generally limited to general adult or paediatric areas. One of the major changes to enrolled nurse scope of practice in recent years is their ability to administer medications and, depending on their level of education and registration notation, they may administer oral or parenteral (including intravenous) medications.

The majority of nurses working in emergency departments are registered nurses who have completed a 3-year bachelor degree typically followed by a 12-month graduate nurse programmme. In many states, 6–12 month transition programmes to specialty practice in emergency nursing are offered to novice nurses wishing to pursue a career in emergency nursing and are often a precursor to postgraduate studies in emergency nursing. Australian emergency nurses have one of the highest standards of education worldwide with the majority holding a graduate certificate or graduate diploma in emergency nursing. Postgraduate qualifications are considered by many as the industry standard for complex emergency nursing roles, such as resuscitation and triage. Triage assessment is a nursing role in Australia and emergency nurses are often responsible for advanced patient assessment, initiation of investigations and symptom relief care prior to medical assessment. Emergency nurses are also primarily responsible for ongoing surveillance and escalation of care in the event of deterioration. Advanced emergency nursing roles for postgraduate qualified emergency nurses are widespread in Australia and nurse initiated pathology, X-rays and analgesia are among common examples. There are also a number of Masters and PhD prepared emergency nurses in Australia working in various advanced clinical roles, joint clinical–academic appointments, nursing education and nursing management.

At the time of writing, there were over 700 endorsed nurse practitioners in Australia and emergency nursing has the largest cohort of nurse practitioners. In Australia, to be endorsed as a nurse practitioner, nurses must complete a clinically based master’s degree or a specific nurse practitioner master’s degree, demonstrate experience in advanced nursing practice in a clinical leadership role in emergency nursing and have undertaken an approved course of study for prescribing scheduled medicines as determined by the NMBA. Nurse practitioners form a key workforce strategy in managing demand for emergency care and are able independently to manage specific patient groups within their defined scope of practice, including prescribing medications, ordering diagnostic tests, referring to specialists and discharging patients home. Published research shows that emergency nurse practitioners can provide safe, efficient and timely care and are a valuable member of the emergency department team [5,6].

Allied health, clerical and other support staff

Allied health, clerical and other ancillary staff are essential to the efficient provision of emergency department services. They should be specifically trained and experienced for emergency department work. Clerical staff have a crucial role, encompassing reception, registration, data entry and communications within and outside the department, as well as maintenance of medical records. Dedicated paramedical staff, including therapists and social workers, are important in providing thorough assessment and management of patients, including participating in disposition decisions and discharge support. Other staff, such as porters and ward assistants, play an important role in releasing clinical staff from non-clinical roles as well as movement of patients within and beyond the emergency department.

Optimizing work practices

Traditional hospital work practices involve systems and tasks that are inefficient for the smooth running of modern, busy emergency departments. In a work environment with a rapid patient throughput and large numbers of staff, efficient work practices are crucial in optimizing clinical performance as well as job satisfaction. A review of staff numbers and seniority cannot provide maximum benefit without consideration of the way the work is done, what tasks are done and by whom.

A review of emergency department work practices can encompass the following principles:

As the emergency department workforce develops greater seniority and specialization and the demands of patient care increase, it is no longer possible to justify outdated work practices. Local research has shown that it is possible to improve clinical service provision by reorganizing roles and tasks in a sustainable way [7]. The opportunity exists to create a work environment that both delivers good clinical service and is rewarding and satisfying for staff.

27.2 Emergency department layout

Matthew WG Chu

Introduction

The emergency department (ED) is a core clinical unit within a hospital. The experience and satisfaction of patients attending the ED are significant contributors to the public image of the hospital. Its primary function is to receive, triage, stabilize and provide emergency care to patients who present with a wide range of undifferentiated conditions which may be critical to semi-urgent in nature. The ED may contribute between 15 and 75% of a hospital’s total number of admissions. It plays an important role in the hospital’s response to major incidents and trauma and in the reception and management of disaster victims. To optimize its core function, the department should be purpose-built, providing a safe environment for patients, their carers and staff. The physical environment includes an effective communication system, appropriate signposting, adequate ambulance access and clear observation of relevant areas from the triage area. There should be easy access to the resuscitation area and quiet and private areas should cater for patients and their relatives. Adequate staff facilities and tutorial areas should be available. Clean and dirty utilities and storage areas are also required.

Design considerations

The design of the department should promote rapid access to every area with the minimum of cross-traffic. There must be proximity between the resuscitation and the acute treatment areas for non-ambulant patients. Supporting areas, such as clean and dirty utilities, the pharmacy room and equipment stores, should be centrally located to prevent staff traversing long distances. The main aggregation of clinical staff will be at the staff station in the acute treatment area. This is the focus around which the other clinical areas should be grouped.

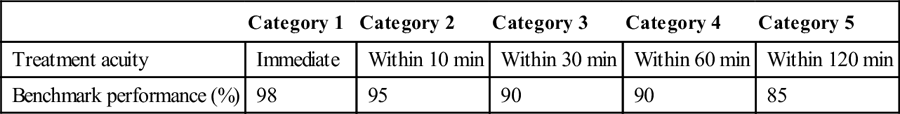

Lighting should conform to national standards and clinical care areas should have exposure to daylight whenever possible to minimize patient disorientation. Climate control is essential for the comfort of both patients and staff. Each clinical area needs to be serviced with medical gases, suction, scavenging units and power outlets. The minimum suggested configuration for each type of clinical area is outlined in Table 27.2.1.

Table 27.2.1

Configurations for clinical areas

| Resuscitation | Acute treatment | Specialty plaster/procedure | Consultation room | |

| Oxygen outlets | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Medical air outlets | 2 | 1 | 1 | – |

| Suction outlets | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Nitrous oxide | 1 | 1 | 1 | – |

| Scavenging unit | 1 | 1 | 1 | – |

| Power outlets | 16 | 8 | 8 | 4 |

Medical gases should be internally piped to all patient care areas and adequate cabling should ensure the availability of power outlets to all clinical and non-clinical areas. Although patient and emergency call facilities are often considered, there is often inadequate provision for telephone and information technology ports. The availability of wireless technology to support equipment, such as computer on wheels (COWS), is desirable. Emergency power must be available to all lighting and power outlets in the resuscitation and acute treatment areas. All computer terminals in the department should have access to emergency power and emergency lighting should be available in all other areas. The electricity supply should be surge protected to protect electronic and computer equipment, physiological monitoring areas should be cardiac protected and other patient care areas should be body protected.

Approximately 35–45% of the total area of the department is circulation space. An example of this would be the provision of corridors wide enough to allow the easy passage of two hospital beds with attached intravenous fluids. Although circulation space should be kept to a minimum, functionality, fire safety and occupational health and safety requirements also need to be considered. The floor covering in all patient care areas should be durable and non-slip, easy to clean, impermeable to water and body fluids and with properties that reduce sound transmission and absorb shocks. Areas accommodating the administrative functions, interview and counselling and support of distressed relatives should be carpeted.

Size and composition of the emergency department

The appropriate size of the ED depends on a number of factors: the census, patient mix and acuity, the admission rate, the defined performance levels manifested in waiting times, the length of stay of patients in the ED and the role delineation of the department. Departments of inadequate size are uncomfortable for patients, often function inefficiently and may significantly impair patient care. Overcrowding of patients increases mortality and morbidity with the risk of infectious disease transmission and increases harmful cognitive stimulation for patients with mental disturbance. For the average Australasian ED with an admission rate of approximately 25–35%, its total internal area (excluding departmental radiological imaging facilities and observation/holding ward) should be approximately 50 m2/1000 yearly attendances. The total number of patient treatment areas (excluding interview, plaster and procedure rooms) should be at least 1/1100 yearly attendances and the number of resuscitation areas should be at least one for every 15 000 yearly attendances. It is recommended that, for departments with average patient acuity, at least half the total number of treatment areas should have physiological monitoring available.

Clinical areas

Individual treatment areas

The design of individual treatment areas should be determined by their specific functions. Adequate space should be allowed around the bed for patient transfer, assessment, performance of procedures and storage of commonly used items. The use of modular storage bins or other materials employing a similar design concept should be considered.

To prevent transmission of confidential information, each area should be separated by solid partitions that extend from floor to ceiling. The entrance to each area should be able to be closed by a movable partition or curtain.

Each acute treatment bed should have access to a physiological monitor. Central monitoring is recommended and monitors should ideally be of the modular type, with recording and print capabilities. The minimum monitored physiological parameters should include oxygen saturation (SpO2), non-invasive blood pressure (NIBP), electrocardiogram (ECG) and temperature. Monitors may be mounted adjacent to the bed on an appropriate pivoting bracket or be movable.

All patient care areas, including toilets and bathrooms, require individual patient call facilities and emergency call facilities, so urgent assistance can be summoned when required. In addition, an examination light, a sphygmomanometer, ophthalmoscope and otoscope, waste disposal unit should all be immediately available. Hand washing facilities should be easily accessible.

Resuscitation area

This area is used for the resuscitation and treatment of critically ill or injured patients. It must be large enough to fit a standard resuscitation bed, allow access to all parts of the patient and allow movement of staff and equipment around the work area. As space must also be provided for equipment, monitors, storage, wash-up and disposal facilities, the minimum suitable size for such a room is usually 35 m2 (including storage area) or 25 m2 (excluding storage area) for each bed space in a multibedded room. The area should also have visual and auditory privacy for both the occupants of the room and for other patients, their carers and relatives. The resuscitation area should be easily accessible from the ambulance entrance and the staff station and be separate from the patient circulation areas. In addition to standard physiological monitoring, invasive pressure, capnography and temperature probe monitoring should be available. Other desirable features include a ceiling-mounted operating theatre light, a radiolucent resuscitation trolley with cassette trays, overhead X-ray and lead lining of walls and partitions between beds.

Acute treatment area

This area is used for the assessment, treatment and observation of patients with acute medical or surgical illnesses. Each bed space must be large enough to fit a standard mobile bed, with adequate storage and circulation space. The recommended minimum space between beds is 2.4 m and each treatment area should be at least 12 m2. All of these beds should be positioned to enable direct observation from the staff station and easy access to the clean and dirty utility rooms, procedure room, pharmacy room and patient shower and toilet.

Single rooms

These rooms should be used for the management of patients who require isolation, privacy or who are a source of visual, olfactory or auditory distress to others. Deceased patients may also be placed there for the convenience of grieving relatives. These rooms must be completely enclosed by floor-to-ceiling partitions but allow controlled visual access and have a solid door. Each department should have at least two such rooms. The isolation room is used to treat potentially infectious patients. The isolation room should be located in an area which does not allow cross infection to other patients in the emergency department. Each isolation room should have negative-pressure ventilation, an ante room with change and scrub facilities and be self-contained with en-suite facilities. A decontamination area should be available for patients contaminated with toxic substances. In addition to the design requirements of an isolation room, this room must have a floor drain and contaminated water trap. The decontamination area should be directly accessible from the ambulance bay and be located in an area which will prevent the ED from being contaminated in the event of a chemical or biological incident. Single rooms should otherwise have the same requirements as acute treatment area bed spaces.

Acute mental health area

This is a specialty area designed specifically for the assessment, protection and containment of patients with actual or potential behavioural disturbances. Ideally, each unit comprises two separate but adjacent rooms allowing for interview, behavioural assessment and treatment functions. Each room should have two doors large enough to allow a patient to be carried through and must be lockable only from the outside. One of the doors may be of the ‘barn door’ type, enabling the lower section to be closed while the upper section remains open. This allows direct observation of and communication with the patient without requiring staff to enter the room. Each room should be squarely configured and be at least 16 m2 in size to enable a restraint team of five members to contain a patient without the potential of injury to a staff member. The examination/treatment room will facilitate physical examination or chemical restraint when indicated. The unit should be shielded from external noise, located as far away as possible from external sources of stimulation (e.g. noise, traffic) and must be designed in such a way that direct observation of the patient by staff outside the room is possible at all times. Services, such as electricity, medical gases and air vents or hanging points, should not be accessible to the patient. It is preferable that furniture be made of material which would prevent it being used as a weapon or inflicting self-harm. A smoke detector should be fitted and closed-circuit television may be considered as an adjunct to direct visual monitoring. Psychiatric Emergency Care Centres (PECC) have been introduced in some hospitals. They are located within or adjacent to an ED and consist of 4–6 rooms with the configurations previously mentioned. Governance is dictated by the local operational policies.

Consultation area

Consultation rooms are provided for the examination and treatment of ambulant patients who are not suffering a major or serious illness. These rooms have similar space requirements to acute treatment area bed spaces. In addition, they are equipped with office furniture with a computer terminal, a radiological viewing panel and a basin for hand washing. Consultation rooms may be adapted and equipped to serve specific functions, such as ENT or ophthalmology treatment, or as part of a fast track area to treat patients with non-complex single system diseases. When the fast track model of care is adopted, the provision of an adjacent subwaiting area for patients waiting for the results of investigations will promote the efficient use of the available floor space.

Plaster room

The plaster room allows for the application of splints, plaster of Paris and for the closed reduction of displaced fractures or dislocations and should be at least 20 m2 in size. Physiological equipment to monitor the patient undergoing procedural sedation or regional anaesthesia is required. Specific features of such a room include a storage area for plaster, splints and bandages; X-ray viewing panel/digital imaging systems facility; provision of oxygen and suction; a nitrous oxide delivery system; a trolley with plaster supplies and equipment; and a sink and drainer with a plaster trap. Ideally, a splint and crutch store should be directly accessible in the plaster room.

Procedure room

A procedure room(s) may be required to undertake procedures, such as lumbar puncture, tube thoracostomy, thoracocentesis, peritoneal lavage, bladder catheterization or suturing. It requires noise insulation and should be at least 20 m2 in size excluding a storage area for minor equipment and supporting sterile supplies. Physiological equipment to monitor the patient undergoing procedures, a ceiling mounted operating theatre light, X-ray viewing panel/digital imaging systems facility, provision of oxygen and suction, a nitrous oxide delivery system, a waste disposal unit and hand washing facilities should all be available.

Staff station

A single central staff area is recommended for staff servicing the different treatment areas, as this enables better communication between, and coordination of, staff members. The staff station in the acute treatment area should be the major staff area within the department. The staff area should be of an ‘arena’ or ‘semi-arena’ design, whereby the main areas of clinical activity are directly observable. The station may be raised in order to give uninterrupted vision of patients and should be centrally located. In larger departments, interlocking pods each involving a centrally located staff station overseeing an acute treatment area may be arranged to ensure patient visibility is maximized. The staff station should be constructed to ensure that confidential information can be conveyed without breach of privacy. Sliding windows and adjustable blinds may be used to modulate external stimuli and a separate write-up area may be considered. Sufficient space should be available to house an adequate number of telephones, computer terminals, printers and data outlets and X-ray viewing panels/digital imaging systems, dangerous drug/medication cupboards, emergency and patient call displays, under-desk duress alarm, valuables storage area, police blood alcohol sample safe, photocopier and stationery store, and write-up areas and workbenches. Direct telephone lines, bypassing the hospital switchboard, should be available to allow staff to receive admitting requests from outside medical practitioners or to participate in internal or external emergencies when the need arises. A dedicated line to the ambulance and police service is essential, as is the provision of a facsimile line. A pneumatic tube system for the transport of specimens to pathology, drugs from pharmacy and the transfer of medical records and imaging requests may also be located in this area.

Short-stay unit

Many EDs possess a short-stay unit, i.e. emergency medical unit (EMU) which is managed under its governance and operates as an extension of the department. The purpose of these units is to manage patients who would benefit from extended observation and treatment but have an expected length of stay of less than 24 hours. It is considered that the minimum functional unit size is eight beds. It is configured along similar lines to a hospital ward with its own staff station. The capacity is calculated to be 1 bed per 4000 attendances per year and its size will be influenced by its function and case mix. As short-stay units are usually high volume users of mental health, social work, physiotherapy, drug and alcohol and community support services, appropriate space should be allocated to allow these services to operate effectively.

Medical assessment and planning unit

A medical assessment and planning unit (MAPU) or medical assessment unit (MAU) is an inpatient hospital unit which may either be co-located or built near an ED. It is managed by the inpatient medical service. The purpose is to facilitate the assessment and treatment of patients who require intensive coordinated multidisciplinary team interventions to minimize the length of stay and optimize health outcomes. The expected length of stay of patients utilizing this type of unit tends to be less than 72 hours. Its configuration and function is determined by case mix and local operational policies. It is usually configured up to 30 beds along similar lines to a hospital ward.

Clinical support areas

The clean utility area requires sufficient space for the storage of clean and sterile supplies and procedural equipment and bench tops to prepare procedure trays. The dirty utility should have sufficient space to house a stainless steel bench top with sink and drainer, pan and bottle rack, bowl and basin rack, utensil washer, pan/bowl washer/sanitizer and slop hopper and storage space for testing equipment (such as for urinalysis). A separate store room may be used for the storage of equipment and disposable medical supplies. A common design fault is to underestimate the amount of storage space required for a modern department. A pharmacy/medication room may be used for the storage of medications and vaccines used by the department and should be accessible to all clinical areas. Entry should be secure with a self-closing door and the area should have sufficient space to house a refrigerator for the storage of heat-sensitive drugs and vaccines. Other design features should include spaces for a linen trolley, mobile radiology equipment, patient trolleys and wheelchairs. Beverage-making facilities for patients and relatives, a blanket-warming cupboard, disaster equipment store, a cleaners’ room and shower and toilet facilities also need to be accommodated. An interview room allows for the interviewing or counselling of patients, carers and relatives in private. It should be acoustically treated and removed from the main clinical area of the department. A distressed relatives’ room should be provided for the relatives of seriously ill or deceased patients. Consideration for the provision of two rooms should be given in larger departments to allow the separation of relatives of patients who have been protagonists in violent incidents or clashes. They should be acoustically insulated and have access to beverage-making facilities, a toilet and telephones. A single-room treatment area should be in close proximity to these rooms to enable relatives to be with dying patients and should be of a size appropriate to local cultural practices.

Non-clinical areas

Waiting area

The waiting area should provide sufficient space for waiting patients as well as relatives or carers and should be open and easily observed from the triage and reception areas. Seating should be comfortable and adequate space should be allowed for wheelchairs, prams, walking aids and patients being assisted. There should be an area where children may play and support facilities, such as television, should be available. Easy access from the waiting room to the triage and reception area, toilets and baby change rooms and light refreshment should be possible. Public telephones should be accessible and dedicated telephones with direct lines to taxi firms should be encouraged. The area should be monitored to safeguard security and patient well-being and it is desirable to have a separate waiting area for children. The waiting area should be at least 5 m2/1000 yearly attendances and should contain at least one seat per 1000 yearly attendances.

Reception/triage area

The department should be accessed by two separate entrances: one for ambulance patients and the other for ambulant patients. It is recommended that each contain a separate foyer that can be sealed by the remote activation of security doors. Access to treatment areas should also be restricted by the use of security doors. Both entrances should direct the patient flow towards the reception/triage area, which should have clear vision to the waiting room and the ambulance entrance. The triage area should have access to a vital signs monitor, computer terminal, hand basin, examination light, telephones, chairs and desk and patient weighing scales. There should be adequate storage space nearby for bandages, minor medical equipment and stationery.

Reception/clerical office

Staff at the reception counter receive patients arriving for treatment and direct them to the triage area. After triage assessment, patients or relatives will generally be directed back to the reception/clerical area, where clerical staff will conduct registration interviews, collate the medical record and print identification labels. Clerks may interview patients or relatives at the bedside but return to the reception area to finalize the administrative details. The counter should provide seating and be partitioned for privacy for interviews. There should be the ability for direct communication between the reception/triage area and the staff station in the acute treatment area to occur. The design should take due consideration for staff safety. This area should have access to an adequate number of telephones, computer terminals, printers, facsimile machines and the photocopier. It should also have sufficient storage space for stationery and medical records.

Tutorial room

This room provides facilities for formal undergraduate and postgraduate education and meetings. It should be in a quiet, non-clinical area near the staff room and offices. Provision should be made to accommodate webcasting, webconferencing, simulation and procedural skills training as well as local lectures and small group teaching. Technological support systems integrating computer, screen projection facilities, broadband access to capitalize on advances in web technology, electronic picture archiving and communication systems are essential. Equipment to support traditional teaching methods utilizing whiteboard, tube X-ray viewer system and examination couch must also be available.

Telemedicine area

Telemedicine is becoming increasing important, particularly for EDs in hospitals which are either remotely located or have limited access to subspecialty support. In these EDs, the telemedicine equipment may be located in the resuscitation area or in a dedicated room where patient encounters, such as mental health assessments, may be undertaken or the transmission of images, such as burns or digital X-rays, expedited. A dedicated facility with appropriate power and communications cabling is necessary. For facilities that receive the telemedicine transmissions, the room should be of a suitable size to allow simultaneous interactions by members of the consulting service teams. It should be in close proximity to the staff station.

Offices

Offices provide space for the administrative, managerial, quality improvement activities, teaching and research roles of the ED. The number of offices required will be determined by the number and type of staff. In a large department, offices may be needed for the director, deputy director, nurse manager, academic staff, specialists, registrars, nurse consultants/practitioners, nurse educator, secretary, social worker/mental health crisis worker, information support officer, research and projects officers and clerical supervisor. Larger departments will require the incorporation of a meeting room into the office area.

Staff facilities

A room should be provided within the department to allow staff a break and to relax from the intensity of their clinical work. Food and drink should be able to be prepared and stored and appropriate table and seating arrangements should be provided in bright and attractive surroundings. It should be located away from patient care areas and have access to natural lighting and appropriate floor and wall coverings. A staff change area with lockers, toilets and shower facilities should also be provided.

Likely developments over the next 5–10 years

Over the last 20 years, EDs have been facing significant challenges. There has been a never-ending increase in demand. The work environment has become increasingly pressured. This has been compounded by resource constraints and the introduction of electronic information management technology. The provision of care has been increasingly complex. Changes in technology have enabled the management of greater numbers of patients in the community who would previously have required hospitalization. As financial pressures on hospitals have also increased, the importance of the ED has grown considerably and modern departments have significantly expanded facilities. Future design considerations are likely to centre on advances in the areas of information technology, telecommunications and newer non-invasive diagnostic modalities. In addition to these technologically driven changes, a greater emphasis will be placed on developing ED design configurations which will support redefined service delivery models to maximize efficient work practices aimed to minimize the number of patient moves, to ensure patients receive timely definitive care and to allow time-critical interventions to be delivered. Computerized patient tracking systems using electronic tags and built-in sensors will provide additional information that may further improve operational efficiency. The electronic medical record will make detailed medical information immediately available and will greatly facilitate the provision of timely care, quality improvement and research activities. Digital radiography, personal communication devices, voice recognition systems, wireless technology and portable computers and expanded telemedicine facilities will make the ED of the future as reliant on electricity and cabling as it is on oxygen and suction.

The increasing age of the population needs also to be considered when designing an ED. Older patients have multiple co-morbidities leading to impaired mobility, vision and balance as well as being at increased risk of delirium due to underlying disease or hospitalization. They are likely to require greater space for the use of mobility aids and require greater shielding from sources of cognitive overstimulation than other patients. Standard hospital trolleys may pose a falls risk and contribute to the development of pressure areas. Strategies, such as the use of alternative hospital beds with pressure relieving mattresses and more comfortable ‘reclining lounge chair’ style seating, should be adopted for this subset of patients. Adequate lighting, the availability of natural lighting and the maintenance of a normal diurnal ‘night–day’ light pattern should be considered in the design to cater for the elderly patients who may spend prolonged periods of time in the emergency department.

27.3 Quality assurance/quality improvement

Diane King

Introduction

A primary role of the emergency department (ED) is to deliver the best possible care to all presenting patients. In order to deliver optimal care, a system of quality management must be part of the culture for all staff and be applied to all functions of the department. A quality framework provides the structure for the wide-ranging aspects of practice that are involved. Quality management requires effective leadership and commitment to improving processes and systems through analysis of data, change of processes and practice, staff engagement accountability and communication. Quality management is a continuous cycle, with measurement and monitoring required to establish that improvement is required in a practice or process, planning of the change, implementation, with re-evaluation and monitoring to ensure the change has the desired effect. Consumer involvement is a fundamental part of quality management. In the emergency setting, consumers include patients, families and carers, staff and the other clinical and hospital staff who interface with the ED.

History

The traditional approach of quality assurance involves a number of retrospective attempts to police various activities of the ED. The types of tools used in this approach are pathology result checking, missed fractures, medical record reviews, death audits and patient complaints.

The role of quality improvement in healthcare has evolved from the 1990s as it became evident that healthcare is prone to significant error and that, despite medical advances and escalating costs, the delivery of safe, acceptable and effective care is frequently lacking. Most industries adopted the quality improvement model to improve safety, reliability and efficiency. The implementation in the healthcare environment is noteworthy for the complexity of its systems, difficulty measuring clinical outcomes and competing priorities [1]. A modern quality system provides a framework that includes monitoring, audit and improvement of the clinical aspects of care, processes and structure, competence of staff, including education and training, and has clear governance and accountability [2].

Definitions

Quality–‘doing those things necessary to meet the needs and reasonable expectations of those we service and doing those things right every time’ [3].

Quality–‘doing those things necessary to meet the needs and reasonable expectations of those we service and doing those things right every time’ [3].

Quality assurance (QA)–‘a system used to establish standards for patient care, to monitor how well standards of care are met, and to correct unwarranted deviations from the standards’ [4]. This implies intervention to correct deficiencies and is often externally driven.

Quality assurance (QA)–‘a system used to establish standards for patient care, to monitor how well standards of care are met, and to correct unwarranted deviations from the standards’ [4]. This implies intervention to correct deficiencies and is often externally driven.

Quality improvement (QI)–raising quality performance to ever increasing levels.

Quality improvement (QI)–raising quality performance to ever increasing levels.

Continuous quality improvement

The Deming cycle (described by WE Deming) is a fundamental tool for the approach to quality in any system. The PDSA (plan, do, study, act) cycle should incorporate the important sequential steps of planning, staff engagement, implementation, measurement, re-measurement and re-evaluation, followed by an improved plan and so on.

A QI system covers a number of dimensions. These are variously described, but include:

access and equity, e.g. waiting times and access to inpatient beds

access and equity, e.g. waiting times and access to inpatient beds

acceptability or patient centredness, e.g. complaint rates, patient satisfaction surveys

acceptability or patient centredness, e.g. complaint rates, patient satisfaction surveys

efficiency: cost-effectiveness and value, e.g. appropriate imaging, avoiding waste.

efficiency: cost-effectiveness and value, e.g. appropriate imaging, avoiding waste.

There are a number of vital characteristics of a CQI programme that are necessary for its successful operation. A CQI programme:

requires leadership (management) commitment and strategic planning

requires leadership (management) commitment and strategic planning

focuses around clear governance structures and accountability

focuses around clear governance structures and accountability

A more detailed outline of TQM is beyond the scope of this book, however, the recent literature abounds with discussion on the various tools used, pitfalls in introduction and so on [5–8].

National bodies

The quality agenda has been facilitated by various bodies, including The Australian Council on Healthcare Standards (ACHS), that, in 1997, introduced its Evaluation and Quality Improvement Programme (EQuIP) as a framework for hospitals to establish quality processes. This is a requirement for accreditation with the ACHS. In 2006, the Australian Commission for Safety and Quality of Health Care was established to oversee improvements in the Australian context (previously the Australian Council for Safety and Quality). In the USA, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement have led the way in the move from QA to QI [9,10].

The Australasian College for Emergency Medicine, the American College of Emergency Physicians and the UK College of Emergency Medicine are facilitating the process of QI by their training role, introduction of clinical indicators, policy development and standards for EDs. In addition, the International Federation for Emergency Medicine (IFEM) has developed a consensus document outlining a framework for measuring quality in 2012 available on the IFEM website.

Quality in the ED

The ED is a complex environment, which involves close interaction with the rest of the hospital and the community. The inputs are uncontrollable and unregulated and the ‘customers’ are under a high level of stress because of the nature of their problems, the unfamiliarity of the environment and the lack of control they perceive at a time when they are feeling personally vulnerable.

The ED is dealing simultaneously with life-threatening illness and minor complaints. It is an area under a high level of scrutiny from all quarters: the patients, the families and friends, the other departments in the hospital and the wider community–both medical and non-medical. This in itself is error prone and is compounded by the fact that many of the staff working in the ED are rotating through the department for relatively short periods of time, are often relatively junior and are undergoing training themselves. This training role is of critical importance in most EDs and must not be forgotten in any process dealing with quality issues. All these aspects of an ED make the maintenance of quality difficult and all the more imperative. In order to establish a system where quality care can be delivered with any degree of reliability, it is important that all staff are committed to the process and that management provides appropriate leadership and resources. The delivery of quality involves a continuing process of data collection (performance measures), analysis, feedback and introduction of strategies to improve the system, followed by re-analysis of the performance measures (the quality cycle).

Common quality measures in ED

The following are not exhaustive but are commonly used measures:

time to thrombolysis or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)

time to thrombolysis or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)

waiting time by triage category

waiting time by triage category

death audits–and morbidity or adverse event reviews

death audits–and morbidity or adverse event reviews

flow measures: 4 hour total ED times, times to inpatient bed

flow measures: 4 hour total ED times, times to inpatient bed

chart audits for specific complaints, e.g. management of headache, abdominal pain, etc.

chart audits for specific complaints, e.g. management of headache, abdominal pain, etc.

time to analgesia: generally and for specific conditions, such as abdominal pain or fractures

time to analgesia: generally and for specific conditions, such as abdominal pain or fractures

time to antibiotic for sentinel diagnoses, such as febrile neutropaenia or pneumonia

time to antibiotic for sentinel diagnoses, such as febrile neutropaenia or pneumonia

trauma audits–missed cervical fractures, delay in craniotomy

trauma audits–missed cervical fractures, delay in craniotomy

X-ray and pathology report follow up

X-ray and pathology report follow up

equipment functioning and supply

equipment functioning and supply

safety of the working environment including, for example, electrical safety or violent incidents

safety of the working environment including, for example, electrical safety or violent incidents

It is clear from the list that the measures are potentially innumerable, that local factors must dictate those areas of special interest and that this will vary from hospital to hospital. In deciding which areas should be measured, it is important to focus on areas critical for patient or staff safety, that are strategically aligned or have been targeted as requiring improvements with which staff engage.

All EDs have common areas where there is high potential for problems to develop and these areas should be routinely monitored. The mechanism for doing this will vary from institution to institution.

Another aspect of the measuring of performance is that the process is one in evolution.

Not only should the quality of the service improve as the measures are improved and re-assessed, but the areas for attention can change and develop with the whole system. Peeling off layers as problems are addressed, exposes new things to improve. Again, this process must be internally driven to be effective. There is little point in collecting an enormous amount of data, unless the process is useful to the improved functioning of the whole system. Those best able to make those improvements should be an integral part of the system.

Likely developments over the next 5–10 years

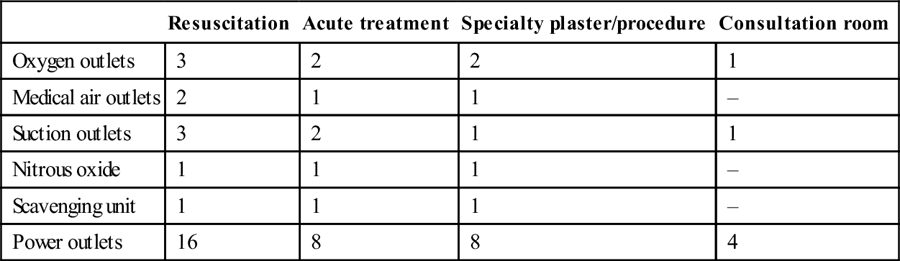

27.4 Business planning

Richard H Ashby

Introduction

Emergency departments (EDs) in public sector health services in Australasia are typically mid-sized clinical units within the organizational structures of hospitals. Staff numbers may range from 30 to over 200 and expenditure budgets from $3 m to over $30 m per annum. ED efficiency directly affects the global efficiency of the healthcare process in the hospital and purchasers are therefore increasingly interested in the value and performance of emergency medicine services. ED managers are being required to report on the dimensions of cost, output, quality and efficiency through a business planning process and other reporting mechanisms in order to justify their level of resourcing.

Types of plans

ED plans are relatively low in the hierarchy of planning instruments that begin with national and state health policy, health departments’ strategic and corporate plans, regional and hospital strategic and business plans and, finally, the business and project plans of individual clinical units and departments. Strategic plans describe how organizations propose to respond to changing technology, altered demographics, shifting paradigms of care and industrial and regulatory reform, as well as issues associated with the cost, quality and accessibility of healthcare. These plans typically look 5–10 years into the future and the ED should reasonably expect to have input at a variety of levels into the strategic planning process.

Project plans, on the other hand, are highly focused on a particular objective outcome to be achieved within a given time frame and with a specified level of resources. Project plans may need to be created by an ED for the implementation of a new and significant piece of technology, major refurbishment or redevelopment or some types of clinical process redesign. However, the most important planning instrument for an ED is its annual business plan.

The business plan

The business plan is an important multipurpose document that needs to be developed by the ED management group, in consultation with hospital management, on an annual basis. At one level, the business plan represents a management contract between the executive of the hospital and the ED. At another level, the business plan provides information to the staff of the department about the agreed targets for revenue and expenditure, activity, efficiency and quality of services to be provided in the next financial year.

Planning process

The plan should be developed by the medical director, business manager and nurse manager of the ED informed by consultation with the wider staff group. It is often useful to include a representative from the hospital’s financial services department early in the process, so that there is a clear understanding of the financial framework for the plan. It is vitally important that the process be informed with as many useful data as possible, including accurate and up-to-date financial and activity statistics and quality and efficiency indicators. The premises, or context, of the business plan needs to be established. Unless there are specific reasons for change, it can usually be assumed that hospital managers will require that the business plan be based on management of the same level of activity at a similar quality to the previous year. In some years, there may be a requirement for a productivity dividend where management expects the same output from a reduced budget or improved performance from the same budget. Other assumptions, relating to estimated wages growth, non-labour cost escalations, leave requirements and so on, should be stated.

The timing of business plan development depends on the government budget cycle for public sector EDs and the timing of the financial year for private sector EDs. In most jurisdictions, this process needs to commence in early January, with the draft business plan available for the hospital executive by the end of February. The process may need to begin much earlier if significant additional or special funding is being sought. Such requests are best handled as separate submissions, which will then need to pass through the various evaluation and approval steps. It is uncommon for special projects requiring substantial funds to be approved and funded within one budget cycle.

A typical business planning cycle is illustrated in Figure 27.4.1.

Business plan content

The ED business plan must address, as a minimum, each of the dimensions of performance, that is, revenue, expenditure, activity, quality and efficiency. A typical index is illustrated in Table 27.4.1. Some hospitals may require that their own format be used.

Table 27.4.1

| 1.0 | Introduction |

| Mission, role, objectives | |

| 2.0 | Executive summary |

| 3.0 | Projected outcomes 2012/2013 |

| 3.1 | Budget–revenue and expenditure |

| 3.2 | Budget variance analysis |

| 3.3 | Staffing profile |

| 3.4 | Activity |

| 3.5 | Quality and efficiency key performance indicators |

| Efficiency indicators | |

| Clinical indicators | |

| Consumer indicators | |

| 4.0 | Budget estimates 2013/2014 |

| 5.0 | SPECIAL ISSUES 2013/2014 |

| Equipment–clinical and non-clinical | |

| <$5000 | |

| >$5000 | |

| Facility maintenance | |

| Projects | |

| Information system replacement | |

| Short-stay unit expansion | |

| Head-injury research |

The introduction to the business plan should be brief. It is often useful to re-state the role and objectives of the ED and of any of its subunits. The executive summary should present an overview of the business plan, including a general perspective on the integrity of the budget and activity targets for the current year and outlining any premises used in the creation of the current plan. Special issues may be highlighted.

Budget

The projected financial outcomes for the current financial year should have been carefully estimated. This projected end-of-year position should be shown in a tabular format against the agreed targets from the previous year’s business plan, as well as the actual outcomes of the previous year. In government organizations, adherence to budget is the highest priority and, therefore, the budget details should be presented first. The management group should have a detailed understanding of every variance from the budget that has occurred in the current year and a note of explanation of variance on every line item should be provided. Because the high fixed costs associated with operating an ED are related to the labour intensity of the service, it is useful to include a section tracking paid full-time equivalent staff, by month, for the current year compared to the previous financial year. This is especially important if there has been an overrun in the labour budget, as the hospital executive will wish to be reassured that this is not due to the employment of excess staff or excessive overtime.

In some jurisdictions, hospitals are funded based on activity, including ED activity, and it is incumbent on the ED to gather accurately and completely all necessary information to optimize this revenue. Similarly, privately insured patients must be identified as well as individuals for whom special funding or revenue premiums apply. Such expectations should be discussed with the finance department.

Activity

The activity of the ED may be shown as total attendances and attendances by category of the Australasian Triage Scale. The admission rate by triage category should also be shown and all values should be tabulated against the previous year’s activity levels. Where an ED operates a short-stay ward or observation unit, the top 20 diagnosis-related groups by volume should be shown, together with the number of total separations, weighted separations and the case-mix index. This information should be available from the finance department. Again, the data should be benchmarked to the previous year. Additional relevant activity data, such as inter-hospital transfers, retrievals and so on, should be included.

Quality and efficiency

Waiting time by triage category is the key quality and efficiency indicator for an ED. The average waiting time per patient in each triage category should be shown, together with the percentage of patients in each triage category who are seen within the timeframe specified by the Australasian Triage Scale. In addition, the percentage of all ED patients seen and admitted, discharged or transferred within 4 hours (Australia-National Emergency Access Target) must be reported against target. These data should be benchmarked against the previous year’s performance and, ideally, also against benchmarking data from similar hospitals elsewhere. Performance against clinical indicators recommended or required by government and other central agencies should also be reported. Additional access indicators include the frequency and duration of ambulance bypass, patient off-stretcher time and admission access block (percentage of total admitted patients spending longer than 8 hours in the ED) should be provided. EDs need to have a complete understanding of the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) that are applicable to their services and have clear plans to achieve these. Dashboard displays of KPI achievement should be regularly published to both managers and staff.

It is appropriate in the section on ‘quality’ that research and educational achievements and plans should be succinctly reported, together with any innovative projects.

Projections

Having summarized the current year’s performance, the remainder of the business plan should be used to present the ED’s projections and estimates for the next financial year. Again, the projected budget should be presented first. This is best done in a tabular format and compared to the previous year’s budget and projected actual expenditure. Any premises, assumptions or caveats related to the projected budget should be included as footnotes to the table. The most common premise relates to the volume and quality of services to be provided and the usual approach is iso-volume/iso-quality; this should not be varied in the business plan unless previously agreed by the hospital executive. Periodically, circumstances will dictate that a hospital vary the desired quality of services, perhaps as part of a strategic initiative to develop the ED or the volume of services in response to changing demographic projections. Apart from anticipated wages growth, it is important for the management group to make reasonable enquiries about predictable leave (such as sabbaticals or long-service leave) and these should be appropriately costed. In the non-labour budget, possible variations in the cost of overseas-sourced clinical supplies or pharmaceuticals due to revaluation of the currency should be considered although, in some jurisdictions, non-labour increments are specified, for budget purposes, across the whole of government. Particular attention should be paid to high-cost areas of pathology, radiology and pharmacy with evidence-based utilization being regularly assessed.

Realistically, most hospital executives will reject a budget proposal that exceeds the previous year’s expenditure, escalated by projected wages growth, unless there are special mitigating factors or a source of funds for the predicted additional expenditure has been identified. For this reason, it is often useful to have three additional sections in the business plan addressing equipment needs, facility maintenance needs and a projects summary.

Equipment

The ED management group should canvass widely among the staff about perceived equipment needs. It is important that the totality of clinical and non-clinical equipment needs is understood and equitably prioritized in order to optimize the efficiency of the whole department. Most hospitals require that equipment requests be stratified according to cost, with items less than $5000 typically being met from a global allocation to the department. Apart from tabulating the need for this lower-priced equipment, a few lines of narrative about each item often assists the executive in ensuring the reasonableness of the request. The table should indicate whether the equipment is new or replacement. New high-cost equipment (e.g. ultrasound machines, computed tomography scanners or arterial blood gas machines) or large-scale renovations or new builds usually require the presentation of a full business case in line with government procurement instructions. The replacement of old, high-cost equipment should be part of a pre-planned hospital programme.

Facility maintenance

All but the newest departments will require some expenditure on maintenance each year. Again, it is useful for the ED management group to undertake a focused tour of all areas of the department to establish an inventory of maintenance needs. Reasonably accurate costings can be obtained from hospital engineering services or external contractors.

Projects

This final section can be used to describe and cost small or large projects to enhance the ED facilities, infrastructure or services. For example, there may be a proposal to establish a 10-bed short-stay unit adjacent to the ED, involving facility redevelopment, the acquisition of clinical and non-clinical equipment (including information systems), staff resourcing and clinical process redesign. This is best presented in a project format, including a clear description of the business need (supported by all available, relevant data), a business case outlining all the costs and benefits and, if possible, additional material, such as architects’ sketches and a project implementation plan, including a project timetable. Professional advice in preparing this documentation is essential.

Private EDs

The overview of business planning presented above is equally relevant to EDs in private hospitals. However, private EDs also need to develop a more robust revenue budget and marketing plan appropriate to their circumstances. The marketing plan will usually be a part of the hospital’s overall arrangements, but the ED should be in a position to report on any changes in referral pattern or on any opportunities to expand the business.

Business plan implementation and monitoring

Soon after the hospital receives its global budget, activity targets and KPIs from government, a short process of negotiation between the hospital executive and the ED management group should take place. This will fine-tune the business plan and, ultimately, permit authorization of the plan and the appropriate delegation for its implementation.

The ED management group should meet at least monthly to review actual performance against the outcomes predicted by the plan. Any variance from the budget in particular should be studied and understood. Remedial action should be taken wherever possible to maintain budget integrity. In many places, the ED management group would meet with the hospital executive at least quarterly to review department performance and to deal with any variation that may have occurred.

27.5 Accreditation, specialist training and recognition in Australasia

James Collier and Allen Yuen

Specialist recognition and registration

Specialist recognition in New Zealand and Australia is handled by the respective medical councils in each country–the Medical Council of New Zealand (MCNZ) and the Australian Medical Council (AMC). In New Zealand, MCNZ handles both specialist recognition (termed vocational registration) and general medical registration. In Australia, the AMC has responsibility for the assessment of International Medical Graduates (IMG) seeking registration to practise medicine in Australia, including specialist recognition of overseas-trained specialists (OTS) and the accreditation of specialist medical colleges. Medical registration (both general and specialist where applicable) is the responsibility of the Medical Board of Australia, which is supported in this role by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA). Medical registration is required to undertake specialist training. All IMG must be both recognized by the AMC and registered with the Medical Board of Australia. There are three pathways to registration that are available to IMG: Competent Authority Pathway, Specialist Pathway and the Standard Pathway.

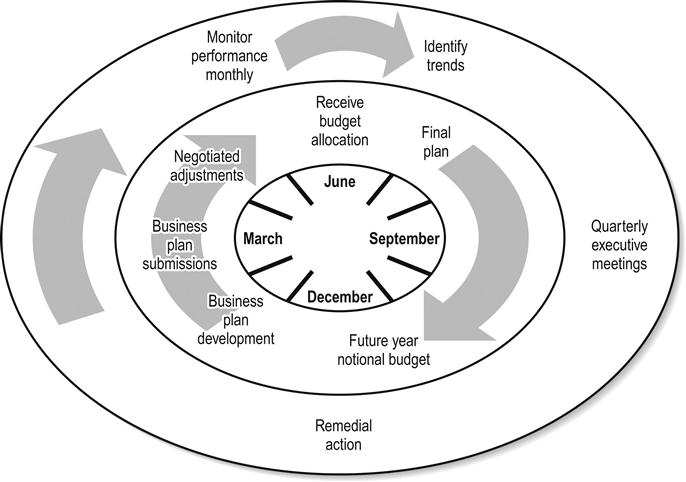

Specialist training in emergency medicine

Specialist medical training is the responsibility of the various specialist medical colleges. Most of these organizations cover both Australia and New Zealand. They are accredited by the AMC. Specialist training in emergency medicine (EM) is covered by the ACEM.

The college provides the framework, standards and supervision for specialist training in EM and successful trainees are granted Fellowship of the ACEM (FACEM).

Training occurs in hospitals and rotations approved by the ACEM for training. Each accredited emergency department (ED) is required to have an appointed Director of Emergency Medicine Training (DEMT). This is the college Fellow with the responsibility of facilitating the delivery of the training programme in that department and hospital. The description below of the training programme reflects the situation in November 2012 [1]. The training programme undergoes regular review and revision.

Basic training

This usually consists of the pre-registration year of practice (internship in Australia or postgraduate year 1 [PGY 1] in New Zealand) and the second year of practice following a doctor’s primary medical degree. It must occur in a variety of clinical rotations and be signed off by the administration of the employing institution.

Provisional training

This usually occurs in the third postgraduate year or beyond. There are three requirements of provisional training:

Advanced training

Advanced training occurs once the trainee has completed all the requirements of provisional training. The ACEM has a detailed curriculum outlining the knowledge and skills required by the completion of advanced training. The main elements are ED training, non-ED training, the minimum paediatric requirement, a research component and completion of the fellowship examination.

ED training

Trainees must complete 30 months of training in accredited EDs. Each accredited ED is allowed to provide training for an individual trainee up to a specified maximum amount of time (6, 12 or 24 months). Training must be in a minimum of 3-month terms. Each term is assessed and signed-off at its completion by the DEMT. As per provisional training, trainee feedback is required at the conclusion of each term.

Hospitals are also assigned a role delineation (major referral, urban district, rural/regional) when they are inspected for training accreditation. Trainees must complete at least 6 months in a major referral hospital and either an urban district or rural/regional hospital.

Non-ED training

Trainees must complete 18 months of training in approved non-ED rotations. These are usually in hospitals accredited for training by the respective college for that specialty. It is required that at least 6 months be spent in critical-care rotations (anaesthesia and/or intensive care). Experience can also be gained in the ACEM accredited special skills terms, such as pre-hospital and retrieval, trauma, toxicology, rural/remote health, ultrasound, research, medical education, simulation, safety and quality and medical administration.

Minimum paediatric requirement

This can be gained by two pathways: completion of a 6-month term in an accredited paediatric emergency department or via completion of a paediatric logbook. With respect to the logbook, this can be utilized during ED and non-ED advanced training involving paediatric (aged 15 years and under) patients. Trainees must log at least 400 substantive encounters with paediatric patients, of which 200 must occur within an ED setting and 100 of these must be from Australasian Triage Scale categories 1, 2 or 3. EDs are given specific accreditation for the use of a paediatric logbook.

Research component

The mandatory learning objectives of the research requirement of training can be met by publishing or presenting a research project to the satisfaction of the ACEM Trainee Research Committee or by successful completion of a minimum of two approved postgraduate subjects from the same course at an Australasian Univeristy.

Fellowship examination

Trainees may attempt the fellowship examination when they are within 1 year of completion of their training. The examination consists of three written sections (multiple choice, short-answer questions and visual aid questions) and three clinical sections (long case, short cases and structured clinical examination). It is run twice a year in various locations across Australia and New Zealand.

Variations to training

Recognition of prior learning can be applied for in line with regulations and upon registration. Up to 2 years of advanced training (up to 1 year of which can be in EM) can be gained overseas, with the prior approval of the ACEM.

Training can also be completed on a part-time basis (at least 50% of the time and conditions of a full-time post) and can be suspended for up to 2 years. All requirements of the training programme must be completed within 12 years of commencement of provisional training.

Dual training

Dual training programmes in paediatric EM (in conjunction with the Royal Australasian College of Physicians) and intensive care medicine (in conjunction with the College of Intensive Care Medicine) are operational.

Recognition of specialist training obtained outside of the ACEM

OTS in EM must apply for specialist recognition from either AMC or MCNZ. In both cases, once the documentation and English language status have been confirmed, the OTS is referred to the ACEM for assessment. The ACEM reviews the applicant’s training, qualifications and experience on paper. If these appear potentially substantially comparable, the ACEM conducts a structured interview for further clarification. The three senior FACEMs on the interview panel review the applicant’s qualifications and experience and determine their level of confidence in the following areas: undergraduate training, basic training, advanced training, postgraduate experience, research and publication profile, education and training experience and administration. Additionally, three topical issues are discussed.

The ACEM then makes a recommendation to the AMC or MCNZ for specialist recognition, further supervision or further training.

The ACEM has a comprehensive website (http://www.acem.org.au) that provides up-to-date information on all aspects of training and other college matters. The AMC (http://www.amc.org.au) and MCNZ (http://www.mcnz.org.nz) also have websites with useful information for overseas-trained doctors wishing to work in either country.

Accreditation

Hospitals seeking accreditation for defined purposes, such as service provision or training, must comply with set standards determined by external institutions which oversee the criteria applicable to such hospitals.

In the case of hospitals overall, the Australian Council on Healthcare Standards (ACHS) determines the service standards of patient care provided by a hospital and its individual departments [2]. The ACHS has included the 10 National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards within its framework and integrated these with standards concerning service delivery, provision of care, workforce planning and management, information management and corporate systems and safety.

The learned colleges, including the ACEM, separately accredit hospitals for their ability to provide postgraduate training, taking the above criteria into account, but placing greater emphasis on the quality of experience, education and supervision for trainees. The items that the ACEM considers and takes into account in any accreditation decision are outlined in the following list from the ACEM guidelines [3]:

Compliance with the ACEM Continuing Professional Development Programme by the FACEM staff.

Compliance with the ACEM Continuing Professional Development Programme by the FACEM staff.

Appropriate levels of staffing with respect to medical, nursing, secretarial and other personnel.

Appropriate levels of staffing with respect to medical, nursing, secretarial and other personnel.

Design and equipment of the department appropriate to the provision of emergency care and training.

Design and equipment of the department appropriate to the provision of emergency care and training.

An appropriate range and level of support services.

An appropriate range and level of support services.

The opportunity for trainee research and the infrastructure supporting this.

The opportunity for trainee research and the infrastructure supporting this.

The ACEM Statement document–Emergency Department Role Delineation.

The ACEM Statement document–Emergency Department Role Delineation.

Accreditation guidelines

Transparent comprehensive ACEM guidelines for mixed and adult EDs seeking training accreditation can be viewed on the ACEM website [3].

The minimum threshold criteria that must be met before an ED can be considered for ACEM training accreditation is 2.5 full time equivalent (FTE) total FACEMs inclusive of the Director and DEMT [3]. The rationale for the minimum threshold relates to the minimum number of specialists required to provide a combination of leadership, mentorship, off-floor training, feedback and assessment and on-floor clinical supervision and feedback.

In addition to this minimum threshold, departments must meet mandatory criteria as outlined below before any level of accreditation can be considered [3]:

appropriate and acceptable standards of patient care

appropriate and acceptable standards of patient care

documented management, admission, discharge and referral policies

documented management, admission, discharge and referral policies

a functional electronic patient information management system

a functional electronic patient information management system

a formal system of quality management; trainees are expected to participate in these activities

a formal system of quality management; trainees are expected to participate in these activities

a formal orientation programme for new staff

a formal orientation programme for new staff

educational programmes for all grades of medical and nursing staff

educational programmes for all grades of medical and nursing staff

access to advice or information which facilitates trainees seeking mentorship if they wish to do so.

access to advice or information which facilitates trainees seeking mentorship if they wish to do so.

College procedure

The ACEM conducts regular (at least 5-yearly) inspections of ACEM training-accredited EDs, to ensure that standards are maintained and that the various criteria for accreditation are met [4,5,6].

In the intervening period, the Accreditation Committee conducts annual reviews of a department’s aggregated Trainee Feedback Reports. Identified issues require clarification, explanation or resolution by departments.

With respect to an accreditation inspection, the completed hospital information questionnaire, ED criteria checklist and any accompanying documents supplied to the inspection team before the inspection are carefully studied. Interviews with administration, department heads, specialists, trainees, nurse managers and educators contribute significantly to the decisions made.

The ED criteria checklist is a checklist against the minimum threshold, mandatory criteria and a number of specific criteria per level of accreditation currently held or desired in the future. An example of these specific criteria for a 24-month department is illustrated below [3]:

With respect to the level of supervision of trainees, the ED requires:

Director(s) of Emergency Medicine Training (DEMT). The DEMT will be a FACEM who is required to be employed at a minimum of 0.5 FTE and undertake clinical work within the emergency department. The DEMT should be at least 3 years post-fellowship (within a Co-DEMT model, this is mandatory for at least one of the DEMT). With reference to provisional and advanced trainees within an emergency department roster, the following should be approximated with respect to the amount of clinical support time required within an emergency department for DEMT duties:

Director(s) of Emergency Medicine Training (DEMT). The DEMT will be a FACEM who is required to be employed at a minimum of 0.5 FTE and undertake clinical work within the emergency department. The DEMT should be at least 3 years post-fellowship (within a Co-DEMT model, this is mandatory for at least one of the DEMT). With reference to provisional and advanced trainees within an emergency department roster, the following should be approximated with respect to the amount of clinical support time required within an emergency department for DEMT duties:

1 hour DEMT clinical support time/trainee/week.

1 hour DEMT clinical support time/trainee/week.

The presence of a FACEM exclusively rostered to clinical duties for at least 98 hours of every week.