CHAPTER 26. Pain and Comfort Management

Linda Wilson, H. Lynn Kane and Kathleen Falkenstein

OBJECTIVES

At the conclusion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Define pain, commonly used terms, and types of pain.

2. Describe nociception: basic process of normal pain transmission.

3. Describe harmful effects of unrelieved pain.

4. Identify pain and comfort management in the perianesthesia settings, including special considerations and key concepts in analgesic therapy.

5. Identify pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, including those for children and management of opioid complications.

6. Define comfort.

7. Identify the contexts in which comfort occurs.

I. PAIN

A. Definition of pain

1. Pain is whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever he or she says it does.

2. Pain is unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage.

B. Types of pain

1. Nociceptive pain—normal processing of stimuli that damages normal tissue or has the potential to do so if prolonged; usually responsive to nonopioids and/or opioids

a. Somatic pain—usually aching or throbbing in quality and is well localized

(1) Arises from:

(a) Bone

(b) Joint

(c) Muscle

(d) Skin

(e) Connective tissue

b. Visceral pain—arises from visceral tissue, such as the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and pancreas

2. Neuropathic pain—abnormal processing of sensory input by the peripheral nervous system or central nervous system (CNS)

a. Treatment usually includes adjuvant analgesics.

b. Centrally generated pain

(1) Deafferentation pain—injury to either the peripheral nervous system or CNS

(2) Sympathetically maintained pain—associated with dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system

c. Peripherally generated pain

(1) Painful polyneuropathies—pain felt along the distribution of many peripheral nerves

(2) Painful mononeuropathies—usually associated with a known peripheral nerve injury, and pain felt at least partly along the distribution of the damaged nerve

C. Definition of commonly used pain terms

1. Acute pain—usually elicited by the injury of body tissues and activation of nociceptive transducers at the site of local tissue damage; pain that extends until period of healing

2. Chronic pain—usually elicited by an injury but may be perpetuated by factors that are both pathogenetically and physically remote from originating cause: pain that extends beyond the expected period of healing (3-6 months since the initiation of pain)

3. Recurrent pain—episodic or intermittent occurrences of pain with each episode lasting for a relatively short period but recurring across an extended period

4. Transient pain—elicited by activation of nociceptors in the absence of any significant local tissue damage; this type of pain ceases as soon as the stimulus is removed (e.g., venipuncture).

5. Addiction—a behavioral pattern of psychoactive substance abuse; addiction is characterized by overwhelming involvement with the use of a medication, the securing of its supply, and a high tendency to relapse.

6. Adjuvant analgesia—a medication that is analgesic in some painful conditions, but that medication’s primary indication is something other than analgesia

7. Allodynia pain—caused by stimulus that does not normally provoke pain

8. Analgesia—absence of the spontaneous report of pain or pain behaviors in response to stimulation that would normally be painful

9. Anxiolytic—a medication used primarily to treat episodes of anxiety

10. Central pain—initiated or caused by primary lesion or dysfunction in the CNS

11. Dysesthesia—an unpleasant, abnormal sensation, whether spontaneous or evoked

12. Hyperalgesia—an increased response to a stimulus that is normally painful

13. Hypoalgesia—diminished pain in response to a normally painful stimulus

14. Hypochondriasis—an excessive preoccupation that bodily sensations and fears represent serious disease despite reassurance to the contrary

15. Malingering—a conscious and willful feigning or exaggeration of a disease or effect of an injury to obtain a specific external gain

16. Neuralgia—pain in the distribution of a nerve or nerves

17. Neurogenic pain—initiated or caused by a primary lesion, dysfunction, or transitory perturbation in the peripheral nervous system or CNS

18. Neuropathic pain—initiated or caused by a primary lesion or dysfunction in the nervous system

19. NMDA— N-methyl- d-aspartate; an example of an NMDA receptor blocker is ketamine.

20. Noxious stimulus—a stimulus that is capable of activating receptors for tissue damage

21. Pain behavior—verbal or nonverbal actions understood by observers to indicate that a person may be experiencing pain and suffering

22. Pain relief—report of reduced pain after a treatment

23. Pain threshold—the least level of stimulus intensity perceived as painful

24. Pain tolerance level—the greatest level of noxious stimulation that an individual is willing to tolerate

25. Paresthesia—an abnormal sensation, whether spontaneous or evoked

26. Physical dependence—a pharmacologic property of a medication (e.g., opioid) characterized by the occurrence of an abstinence syndrome after abrupt discontinuation of the substance or administration of an antagonist; this does not imply addiction

27. Psychogenic pain—report of pain attributed primarily to psychological factors, usually in the absence of an objective physical pathology that could account for pain

28. Suffering—reaction to the physical or emotional components of pain with a feeling of uncontrollability, helplessness, hopelessness, intolerability, and interminableness

29. Tolerance—a physiological state in which a person requires an increased dosage of a drug to sustain a desired effect

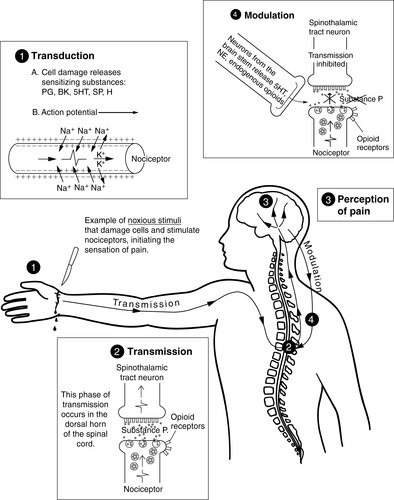

D. Nociception: basic process of normal pain transmission

1. Transduction—conversion of one energy from another

a. Process occurs in the periphery when a noxious stimulus causes tissue damage.

b. Damaged cells release substances that activate or sensitize nociceptors.

c. This activation leads to the generation of an action potential.

d. Sensitizing substances released by damaged cells

(1) Prostaglandins

(2) Bradykinin

(3) Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine)

(4) Substance P

(5) Histamine

e. An action potential results from:

(1) Release of the preceding sensitizing substances (nociceptive pain)

(2) A change in the charge along the neuronal membrane

(3) Abnormal processing of stimuli by the nervous system neuropathic pain

(4) A change in the charge along the neural membrane

(a) Change in charge occurs when sodium ion (Na +) moves into the cell and other ion transfers occur.

2. Transmission—the action potential continues from the site of damage to the spinal cord and ascends to higher centers; transmission may be considered in three phases.

a. Injury site to spinal cord

(1) Nociceptors terminate in the spinal cord.

b. Spinal cord to brainstem and thalamus

(1) Release of substance P and other neurotransmitters continues the impulse across the synaptic cleft between the nociceptors and the dorsal horn neurons.

(2) From the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, neurons such as the spinothalamic tract ascend to the thalamus.

(3) Other tracts carry the message to different centers in the brain.

c. Thalamus to cortex

(1) Thalamus acts as a relay station sending the impulse to central structures for processing.

3. Perception of pain—conscious experience of pain

4. Modulation—inhibitor nociceptive impulses

a. Neurons originating in the brain stem descend to the spinal cord.

b. Released substances inhibit the transmission of nociceptive impulses.

(1) Endogenous opioid

(2) Serotonin

(3) Norepinephrine (Figure 26-1)

|

| FIGURE 26-1 ▪

Pain transmission. BK, Bradykinin; H, histamine; 5HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin); NE, norepinephrine; PG, prostaglandins; SP, substance P.

(From McCaffery M, Pasero C: Pain: Clinical manual, St Louis, 1999, Mosby.)

|

E. Harmful effects of unrelieved pain

1. Endocrine

a. Increase in the following:

(1) Corticotropin (Adrenocorticotropic hormone—ACTH)

(2) Cortisol

(3) Antidiuretic hormone

(4) Catecholamines

(a) Epinephrine

(b) Norepinephrine

(5) Growth hormone

(6) Renin

(7) Angiotensin II

(8) Aldosterone

(9) Glucagons

(10) Interleukin-1

b. Decrease in:

(1) Insulin

(2) Testosterone

2. Metabolic

a. Gluconeogenesis

b. Hepatic glycogenolysis

c. Hyperglycemia

d. Glucose intolerance

e. Insulin resistance

f. Muscle protein catabolism

g. Increased lipolysis

3. Cardiovascular

a. Increase in the following

(1) Heart rate

(2) Cardiac output

(3) Peripheral vascular resistance

(4) Systemic vascular resistance

(5) Hypertension

(6) Coronary vascular resistance

(7) Myocardial oxygen consumption

(8) Hypercoagulation

(9) Deep vein thrombosis

4. Respiratory

a. Decreased flows and volumes

b. Atelectasis

c. Shunting

d. Hypoxemia

e. Decreased cough

f. Sputum retention

g. Infection

5. Genitourinary

a. Decreased urinary output

b. Urinary retention

c. Fluid overload

d. Hypokalemia

e. Hyperkalemia

6. Gastrointestinal (GI)

a. Decreased gastric motility

b. Decreased bowel motility

7. Musculoskeletal

a. Muscle spasm

b. Impaired muscle function

c. Fatigue

d. Immobility

8. Cognitive

a. Reduction in cognitive function

b. Mental confusion

9. Immune response

a. Depression

10. Developmental

a. Increased behavioral and physiological response to pain

b. Altered temperaments

c. Higher somatization

d. Infant distress behavior

e. Possible altered development of the pain system

f. Increased vulnerability to stress disorders

g. Addictive behavior

h. Anxiety states

i. Cultural considerations

11. Debilitating chronic pain syndromes

a. Postmastectomy pain

b. Postthoracotomy pain

c. Phantom pain

d. Postherpetic neuralgia

12. Quality of life

a. Sleeplessness

b. Anxiety

c. Fear

d. Hopelessness

e. Increase thoughts of suicide

F. Special considerations

1. Key principle: all patients deserve the best possible pain relief and comfort measures that can be safely provided.

2. The following emphasizes some important key elements of care in patients with special needs.

a. Elderly patients

(1) Same pain assessment tools may be used in both cognitively intact elderly and younger patients.

(2) Report of pain may be altered.

(a) Physiological

(b) Psychological

(c) Cultural differences

(3) Often have acute and chronic painful diseases

(a) More than 80% have various forms of arthritis.

(b) Most will have acute pain at some time.

(4) Have multiple diseases

(5) Take many medications

(6) Prevalence of pain two-fold higher in those older than 60

(7) Increased sensitivity to therapeutic and toxic effects of analgesics

(a) Influenced by age-induced changes

(i) Drug absorption

(ii) Distribution

(iii) Metabolism

(iv) Elimination

(8) Prone to constipation when given opioid analgesic

(9) All nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) must be used with caution because of increased risk.

(a) GI problems

(b) Renal insufficiency

(c) Platelet dysfunction

(10) More sensitive to analgesic effects of opioid medications

(a) May experience a higher peak effect

(b) Longer duration of pain relief

(c) Reduce initial dose by 25% to 50%.

(d) Careful dose titration

(e) Close monitoring of patient’s responses

b. Patients with known or suspected chemical dependency or history of such

(1) Usually experience traumatic injuries

(2) Experience a variety of health problems

(3) Possible withdrawal caused by opioid absence may stimulate sympathetic nervous system.

(a) Restlessness

(b) Tachycardia

(c) Sleeplessness

(4) Focus on managing pain or discomfort, not detoxification.

(5) There is no evidence that:

(a) Withholding analgesics will increase the likelihood of recovery from addiction

(b) Providing analgesics will worsen addiction

(6) Higher loading and maintenance doses of opioids may be required to reduce intensity of pain.

(7) Provide nonpharmacological interventions concomitantly with pharmacological interventions.

(8) May refer to an addiction specialist for ongoing care and rehabilitation after the acute pain period

(9) Patients with chronic alcoholism who are actively drinking

(a) Maintain on benzodiazepines or alcohol throughout the intraoperative and postoperative periods to prevent withdrawal reaction or delirium tremens.

(b) Dosage based upon individual evaluation

c. Concurrent medical conditions

(1) Involving either hepatic or renal impairment: result is medication accumulation

(a) Elimination decreased in patient with renal failure

(b) Doses must be lowered or given less frequently.

(2) Observe patient with respiratory insufficiency and chronic obstructive disease.

(3) Observe patient taking anxiolytics or other psychoactive medications for interaction with pain medications.

d. Patients with shock, trauma, or burns

(1) Observe for cardiorespiratory instability in the first hour of injury.

(a) Carefully titrate opioid dosage.

(b) Monitor closely.

(2) Peripheral nerve damage may result in neuropathic pain requiring adjuvant analgesics.

(a) Tricyclic antidepressants

(b) Anticonvulsants

(c) Opioids

(d) Nonopioids

e. Patients having procedures outside the operating room

(1) Analgesia may be withheld for a painful procedure when:

(a) Immediate treatment of cardiorespiratory instability required

(b) A competent patient declines treatment.

(2) Clinicians giving anesthetic or analgesic agents must understand:

(a) Proper technique of administration

(b) Dosage

(c) Contraindications

(d) Side effects

(e) Treatment of overdose

(3) Monitor closely according to institutional policy when analgesic or adjuvant given.

f. Patients with chronic pain in perianesthesia setting

(1) Require special consideration and planning for pain management

(2) May request consultations with an acute pain management service and/or anesthesiologist familiar with chronic pain management

(3) Individualized detailed pain management plan communicated through all phases of perioperative care

g. Pediatric patients

(1) Provide adequate and unhurried preparation of the child and family.

(a) Parental prediction of the child’s response highly correlates with the actual degree of distress.

(2) Optimally manage preexisting pain.

(3) Requires frequent assessment and reassessment

(a) Presence

(b) Amount

(c) Quality

(d) Location of pain

(4) Emotional distress accentuates the experience of pain.

(a) Focus on prevention.

(b) Reduce anticipated pain.

(5) Inclusion of parents or caregiver essential to pain assessment

(6) Tailor assessment strategies to the development level and personality of the child.

(7) Physiological indicators may vary among children who are experiencing pain.

(8) Interpretation of physiological indicators crucial

(a) In the context of the clinical condition

(b) In conjunction with other assessment methods

(9) Effective interaction key to effective pain management

(10) Preferences of the child and family warrant respect and careful consideration.

(11) Primary obligation to ensure safe and competent care

(12) Environmental factors such as cold or crowded rooms and alarms on machines can intensify distress.

h. Obstetric patients

(1) During pregnancy

(a) Analgesic considerations

(i) May increase vascular resistance or decrease placental flow

(ii) May cause transient or permanent harm to the fetus or infant

(b) Encourage the use of nonpharmacological pain-relieving measures and caution against the use of analgesics.

(c) Analgesics

(i) Acetaminophen: safe for use in therapeutic doses

(ii) NSAIDs: generally not recommended

(iii) Opioid analgesics: a long history of safely relieving perinatal pain

[a] Mu-agonists are recommended.

[1] Morphine

[2] Hydromorphone

[3] Fentanyl

[4] Oxycodone

[5] Hydrocodone

[6] Meperidine: not recommended as first-line opioid

(iv) Adjuvant analgesics are used to treat pain of neuropathic origin.

[a] Local anesthetics

[b] Antidepressants

[c] Anticonvulsants

[d] Corticosteroids

[e] Benzodiazepines

(v) Types of pain related to pregnancy

[a] Round ligament pain (sides of the uterus)

[b] Headache

[c] Back pain

[d] Pyrosis (heartburn)

[e] Braxton Hicks contractions

(2) During childbirth

(a) Labor pain considered the most agonizing of pain syndromes

(b) Factors contributing to suffering

(i) Lack of appropriate analgesics

(ii) Lack of support person

(iii) Hunger

(iv) Fatigue

(v) Low self-confidence

(c) Alternate pain management methods

(i) Relaxation

(ii) Distraction

(iii) Imagery

(iv) Effleurage

(v) Water heat

(vi) Acupuncture

(d) Analgesics

(i) Mu-opioid agonists commonly used

(ii) Meperidine not recommended

(iii) Local anesthetic bupivacaine used most often for epidural analgesia and anesthesia

(iv) Benzodiazepines recommended for muscle spasm only, and their use for childbirth not recommended

(e) Regional techniques used

(i) Intrathecal analgesia

(ii) Epidural analgesia and anesthesia

(iii) Combined spinal-epidural analgesia

3. During postpartum

a. Effective pain management very important postpartum

(1) Clotting factors elevated

(2) Increased risk for thrombophlebitis

(3) Pain relief should be aimed at maximizing patient’s mobility.

b. Bonding with baby encouraged

c. Types of pain

(1) Uterine contractions

(2) Episiotomy

(3) Breast

(4) Nipple

(5) Post Cesarean section

4. During breast-feeding

a. Secretion of medications into breast milk: considerations

(1) High lipid solubility

(2) Low molecular weights

(3) Nonionized state

5. Neonates may receive 1% to 2% of the maternal dose of a medication.

a. Medicating right before or right after breast-feeding may minimize medication transfer.

b. Acetaminophen safe

c. NSAIDs generally not recommended

d. Opioid analgesics

(1) Codeine

(2) Fentanyl

(3) Methadone

(4) Morphine

e. Adjuvant analgesic for neuropathic pain

G. Key concepts in analgesic therapy

1. Balanced analgesia

a. Continuous multimodal approach in treating pain

b. Considered as the ideal by experts

c. Use combined analgesic regimen.

(1) Reduces the likelihood of significant side effects from a single agent or method

d. Opioids commonly used in the balanced analgesia approach

(1) Administered preemptively as well as after the noxious event occurs

2. Preemptive analgesia

a. Intervention implemented before noxious stimuli are experienced

b. Designed to reduce the CNS impact of these stimuli

c. NSAIDs reduce activation and centralization of nociceptors.

d. Local anesthetics used to block sensory inflows

e. Opioids act centrally to control pain.

f. Local anesthetics provide effective preemptive analgesia.

(1) Long-acting regional blocks indicated before painful procedures

(2) Indicated whenever pain management expected to be difficult

3. Around-the-clock (ATC) dosing

a. Two basic principles of providing effective pain management

(1) Preventing pain

(2) Maintaining a pain rating that is satisfactory to patient

b. Indicated whenever pain is predicted to be present for at least 12 to 24 hours

c. ATC dosing should be accompanied by provision of additional analgesic doses to relieve:

(1) Breakthrough pain

(2) Ongoing extreme pain

d. Short-acting mu-agonist opioid analgesics used in breakthrough pain

(1) Recommend that rescue doses are the same route and opioid as the ATC.

e. Pain can have a sudden or gradual onset, and it can be brief or prolonged.

4. As needed (PRN) dosing

a. Ordinarily, the patient requests analgesia.

b. Effective PRN dosing requires active participation of patient.

(1) Prompt patient to ask for medication before the pain is severe or out of control.

c. Opioid analgesic is appropriate.

d. ATC can be replaced with PRN dosing when acute pain is resolved.

5. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA)

a. An interactive method that permits patients to treat their pain by self-administering doses of analgesics.

b. Initiating PCA in the post anesthesia care unit (PACU) is recommended.

(1) Allows evaluation of patient’s response to the therapy early in postoperative course

(2) Prevents delays in analgesia on the nursing unit

c. Types

(1) Subcutaneous infusions

(a) Rarely used for acute pain management

(i) Slow onset

(ii) When there is limited intravenous (IV) access

(iii) Oral opioids not tolerated

(iv) Intermittent bolusing for children

(b) Hydromorphone and morphine most commonly used

(c) Methadone causes irritation to the site.

(d) Absorption and distribution dependent on needle placement and the patient’s adipose tissue

(e) Opioid concentrations high because infusion volumes must be limited

(i) Most patients can absorb 2 or 3 mL/h.

(ii) Some can absorb 5 mL/h.

(iii) Infusion pump must be able to deliver in tenths of milliliter (0.1 mL/h).

(f) Primary site of infusion

(i) Left or right subclavicular anterior chest wall

(ii) Left, right, or center abdomen

(iii) Upper arms

(iv) Thighs

(v) Buttocks

(2) IV PCA

(a) Used for immediate analgesic effect for acute, severe escalating pain

(i) Includes bolus

(ii) Continuous infusion

(b) A steady state maintained better with continuous infusion

(c) Duration of analgesia by bolus administration is dose dependent; the higher the dose, usually the longer the duration.

d. Special considerations for pediatric IV PCA

(1) Safe and effective use in children older than 5 years

(2) Instruct parents and caregivers that only the designated child’s pain manager should press the PCA.

(3) Adult and pediatric selection guidelines are the same in the use of PCA.

(4) Principles of starting dose estimates and titration for adults apply also to children.

6. Intraspinal analgesics (neuraxial)

a. Epidural—needle inserted in epidural space

b. Intrathecal—needle inserted in subarachnoid space

c. Catheters removed after 2 to 4 days

d. Long-term epidural and intrathecal catheters can be placed surgically.

(1) Tunneled subcutaneously to an implanted pump

(2) Subcutaneous pocket in the abdomen for pump

(3) Implanted catheters easier to maintain

(4) Risk of infection less

e. Contraindications for intraspinal use

(1) Patient refusal

(2) Untreated sepsis, which could involve the site of injection

(3) Shock

(4) Hypovolemia

(5) Coagulopathies

f. Contraindications to use of opioid analgesia

(1) Contraindications to epidural catheter insertion

(2) History of adverse reactions to opioid medications

(3) Central sleep apnea

(4) Lack of familiarity of technique by patient caretakers

g. Potential complications

(1) Total or high spinal blockade

(2) IV injection

(3) Dural puncture resulting in a dural puncture headache

(4) Bleeding resulting in an epidural hematoma

(5) Catheter problems including:

(a) Migration of epidural catheter

(b) Breakage of catheter

(c) Infection

h. Analgesics and local anesthetics commonly used

(1) Fentanyl

(2) Sufentanil

(3) Morphine

(4) Hydromorphone

(5) Ropivacaine

(6) Bupivacaine

7. Transdermal

a. Check for transdermal fentanyl patch placed by the patient for chronic pain.

b. Fentanyl patches deliver the synthetic opioid passively.

c. Consider fentanyl patch dose in the total opioid patient receives.

H. Site-specific surgery

1. Dental surgery

a. Patient’s anxiety frequently disproportionate to the safety of the procedure

b. May benefit from behavioral or pharmacological anxiolytic therapy

c. Manage mild pain associated with uncomplicated dental care with NSAIDs

(1) Given preprocedure, shown to delay onset of postoperative pain and lessen its severity

d. Preoperative treatment can delay onset of pain postoperatively on more traumatic and intense procedure.

(1) Ibuprofen

(2) Application of long-acting local anesthetic

e. May require an opioid added to pain regimen

(1) Codeine

(2) Oxycodone

2. Radical head and neck

a. Alternate routes for pain therapy may be required.

(1) Gastrostomy

(2) Jejunostomy

b. Presence of tracheostomy may limit ability to describe pain or response to analgesic.

c. Positioning of head and neck is critical.

d. Positioning and padding

(1) Minimize muscle spasm.

(2) Minimize pressure point ulcer breakdown.

e. Painful swallowing may require modification of diet.

(1) Liquids and soft foods

(2) Occasional use of topical anesthetics such as viscous lidocaine

3. Neurosurgery

a. Opioid analgesics may affect abnormal neurological signs and symptoms that may be present.

(1) Pupillary reflexes

(2) Level of consciousness

b. Balance analgesia to provide appropriate neurological monitoring.

c. NSAIDs may be considered.

(1) No effect on level of consciousness or pupillary reflexes

(2) Risk of coagulopathy or hemorrhage

4. Thoracic surgery

a. Preexisting disease, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, common

b. May have had prior medical treatment such as chemotherapy

c. Epidural analgesia or neural blockade with local anesthetics improves pulmonary functions.

d. Local epidural infusion provides dermatome bands of pain relief above and below epidural insertion site (T4 to T10).

e. For patient experiencing pain above T4, ketorolac IV may provide excellent analgesia.

(1) The potential risks of bleeding must be evaluated before a first dose.

(2) Ketorolac IV might be used for 24 hours after surgery.

(3) Use of opioids to reduce postoperative pain after thoracotomy is well documented.

f. Use of PCA has:

(1) Incrementally improved analgesia

(2) Increased patient satisfaction

(3) Improved pulmonary function

(4) Contributed to early recovery and discharge

5. Cardiac surgery

a. Close observation is essential to distinguish postoperative pain (chest wall and pleura) from cardiac pain (may be related to myocardial ischemia).

b. Median sternotomy incision may require anesthetic induction of high dose of opioids.

c. As techniques of less invasive surgical approaches progress and gain in popularity, anesthesia induction requirements may decrease.

6. Upper abdominal surgery

a. In preparation for surgery, review pain management choices and care plans with the patient.

(1) Treatment for inadequate pain relief

(2) Treatments for side effects

(3) Scheduled postoperative opioid medication may be withheld in the event of respiratory depression, nausea, and vomiting.

7. Lower abdominal surgery

a. Pain management based on same principle as that for upper abdominal surgery

b. Pain management during active labor requires special expertise and caution because side effects may impair fetal well-being.

c. Epidural local anesthesia beneficial in suppressing pain and surgical stress responses

d. Pain after procedures on the anus can be severe and require adjunctive measures.

(1) Stool softeners

(2) Dietary manipulation

(3) Local anesthetic suppositories

8. Back surgery

a. Patient may experience chronic pain.

(1) May be depressed, anxious, and irritable

(2) Have a tolerance level to opioid medications

b. Some procedures may limit use of epidural and spinal delivery of pain medications.

c. Patient can experience paraspinal muscle spasm—appropriate to add muscle relaxant to supplement conventional opioid therapy.

d. Require careful monitoring of neurological functions

9. Surgery on extremities

a. High degree of morbidity related to venous thromboembolic complications must be considered.

b. Pain control postoperatively should allow early ambulation and movement in postoperative period.

c. Pain therapy should not interfere with monitoring patient’s neurologic functions.

d. Epidural analgesia allows early mobility and minimizes complications from thromboemboli.

10. Soft tissue surgery

a. Local soft tissue resections: patient usually obtains pain control with oral opioids.

b. Patient anxious about potential biopsy results may need adjuvant medication or nonpharmacological therapy.

I. Pharmacologic treatment of pain

1. Equianalgesic dose chart (Table 26-1)

| ATC, Around-the-clock; CR, oral controlled-release; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; NR, not recommended; NS, nasal spray; OT, oral transmucosal; PO, oral; R, rectal; SC, subcutaneous; SL, sublingual; TD, transdermal; UK, unknown. | ||||||

| ‡‡65 to 130 mg = approximately one sixth of all doses listed in this chart. | ||||||

| *Duration of analgesia is dose dependent; the higher the dose, usually the longer the duration. |

||||||

| †As in, for example, MS Contin. |

||||||

| ‡IV boluses may be used to produce analgesia that lasts approximately as long as IM or SC doses. However, of all routes of administration, IV produces the highest peak concentration of the medication, and the peak concentration is associated with the highest level of toxicity (e.g., sedation). To decrease the peak effect and lower the level of toxicity, IV boluses may be administered more slowly (e.g., 10 mg of morphine over a 15-minute period), or smaller doses may be administered more often (e.g., 5 mg of morphine every 1-1.5 hours). |

||||||

| §At steady state, slow release of fentanyl from storage in tissues can result in a prolonged half-life up to 12 hours. |

||||||

| |Equianalgesic data not available. |

||||||

| ¶The recommendation that 1.5 mg of parenteral hydromorphone is approximately equal to 10 mg of parenteral morphine is based on single-dose studies. With repeated dosing of hydromorphone (e.g., PCA), it is more likely that 2 to 3 mg of parenteral hydromorphone is equal to 10 mg of parenteral morphine. |

||||||

| #In opioid-tolerant patient converted from continuous IV hydromorphone to continuous IV methadone, start with 10% to 25% of the equianalgesic dose. |

||||||

| **In opioid-tolerant patient converted to methadone, start PO dosing PRN with 10% to 25% of equianalgesic dose. |

||||||

| ††As in, for example, Oxycontin |

||||||

| §§Used in combination with mu agonists, may reverse analgesia and precipitate withdrawal in opioid-dependent patient. |

||||||

| | |In opioid-naïve patient who is taking occasional mu agonists, such as codeine or oxycodone, the addition of butorphanol nasal spray may provide additive analgesia. However, in an opioid-tolerant patient, such as one receiving ATC morphine, the addition of butorphanol nasal spray should be avoided because it may reverse analgesia and precipitate withdrawal. |

||||||

| From McCaffery M, Pasero C: Pain: Clinical manual, ed 2, St Louis, 1999, Mosby. | ||||||

| Opioid | Parenteral (IM/SC/IV) (over ~4 h) | Oral (PO) (over ~4 h) | Onset (min) | Peak (min) | Duration* (h) | Half-life (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MU AGONISTS | ||||||

| Morphine | 10 mg | 30 mg | 30-60 (PO) | 60-90 (PO) | 3-6 (PO) | 2-4 |

| 30-60 (CR) † | 90-180 (CR) † | 8-12(CR) † | ||||

| 30-60 (R) | 60-90 (R) | 4-5 (R) | ||||

| 5-10 (IV) | 15-30 (IV) | 3-4 (IV) *‡ | ||||

| 10-20 (SC) | 30-60 (SC) | 3-4 (SC) | ||||

| 10-20 (IM) | 30-60 (IM) | 3-4 (IM) | ||||

| Codeine | 130 mg | 200 mg NR | 30-60 (PO) | 60-90 (PO) | 3-4 (PO) | 2-4 |

| 10-20 (SC) | UK (SC) | 3-4 (SC) | ||||

| 10-20 (IM) | 30-60 (IM) | 3-4 (IM) | ||||

| Fentanyl |

100 mcg/h parenterally and transdermally ≈4 mg/h morphine parenterally;

1 mcg/h transdermally ≈ morphine 2 mg/24 h orally

|

— | 5 (OT) | 15 (OT) | 2-5 (OT) | 3-4§ |

| 1-5 (IV) | 3-5 (IV) | 0.5-4 (IV) *‡ | ||||

| 7-15 (IM) | 10-20 (IM) | 0.5-4 (IM) | ||||

| 12-16 h (TD) | 24 h (TD) | 48-72 (TD) | 13-24 (TD) | |||

| Hydrocodone (as in Vicodin, Lortab) | — | 30 mg| NR | 30-60 (PO) | 60-90 (PO) | 4-6 (PO) | 4 |

| Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) | 1.5 mg¶ | 7.5 mg | 15-30 (PO) | 30-90 (PO) | 3-4 (PO) | 2-3 |

| 15-30 (R) | 30-90 (R) | 3-4 (R) | ||||

| 5 (IV) | 10-20 (IV) | 3-4 (IV) *‡ | ||||

| 10-20 (SC) | 30-90 (SC) | 3-4 (SC) | ||||

| 10-20 (IM) | 30-90 (IM) | 3-4 (IM) | ||||

| Levorphanol (Levo-Dromoran) | 2 mg | 4 mg | 30-60 (PO) | 60-90 (PO) | 4-6 (PO) | 12-15 |

| 10 (IV) | 15-30 (IV) | 4-6 (IV) *‡ | ||||

| 10-20 (SC) | 60-90 (SC) | 4-6 (SC) | ||||

| 10-20 (IM) | 60-90 (IM) | 4-6 (IM) | ||||

| Meperidine (Demerol) | 75 mg | 300 mg NR | 30-60 (PO) | 60-90 (PO) | 2-4 (PO) | 2-3 |

| 5-10 (IV) | 10-15 (IV) | 2-4 (IV) *‡ | ||||

| 10-20 (SC) | 15-30 (SC) | 2-4 (SC) | ||||

| 10-20 (IM) | 15-30 (IM) | 2-4 (IM) | ||||

| Methadone (Dolophine) | 10 mg# | 20 mg** | 30-60 (PO) | 60-120 (PO) | 4-8 (PO) | 12-190 |

| UK (SL) | 10 (SL) | UK (SL) | ||||

| 10 (IV) | UK (IV) | 4-8 (IV) *‡ | ||||

| 10-20 (SC) | 60-120 (SC) | 4-8 (SC) | ||||

| 10-20 (IM) | 60-120 (IM) | 4-8 (IM) | ||||

| Oxycodone (as in Percocet, Tylox) | — | 20 mg | 30-60 (PO) | 60-90 (PO) | 3-4 (PO) | 2-3 |

| 30-60 (CR) †† | 90-180 (CR) †† | 8-12 (CR) †† | 4.5 (CR) | |||

| 30-60 (R) | 30-60 (R) | 3-6 (R) | ||||

| Oxymorphone (Numorphan) | 1 mg | (10 mg R) | 15-30 (R) | 120 (R) | 3-6 (R) | 2-3 |

| 5-10 (IV) | 15-30 (IV) | 3-4 (IV) *‡ | ||||

| 10-20 (SC) | UK (SC) | 3-6 (SC) | ||||

| 10-20 (IM) | 30-90 (PO) | 3-6 IM | ||||

| Propoxyphene (Darvon) | 30-60 (PO) | 60-90 (PO) | 4-6 (PO) | 6-12 | ||

| Buprenorphine§§ (Buprenex) | 0.4 mg | — | 5 (SL) | 30-60 (SL) | UK (SL) | 2-3 |

| 5 (IV) | 10-20 (IV) | 3-4 (IV) *‡ | ||||

| 10-20 (IM) | 30-60 (IM) | 3-6 (IM) | ||||

| Butorphanol§§ (Stadol) | 2 mg | — | 5-15 (NS) | | | 60-90 (NS) | 3-4 (NS) | 3-4 |

| 5 (IV) | 10-20 (IV) | 3-4 (IV) *‡ | ||||

| 10-20 (IM) | 30-60 (IM) | 3-4 (IM) | ||||

| Dezocine (Dalgan) | 10 mg | — | 5 (IV) | UK (IV) | 3-4 (IV) *‡ | 2-3 |

| 10-20 (IM) | 30-60 (IM) | 3-4 (IM) | ||||

| Nalbuphine§§ (Nubain) | 10 mg | — | 5 (IV) | 10-20 (IV) | 3-4 (IV) *‡ | 5 |

| <15 (SC) | UK (SC) | 3-4 (SC) | ||||

| <15 (IM) | 30-60 (IM) | 3-4 (IM) | ||||

| Pentazocine§§ (Talwin) | 60 mg | 180 mg | 15-30 (PO) | 60-180 (PO) | 3-4 (PO) | 2-3 |

| 5 (IV) | 15 (IV) | 3-4 (IV) *‡ | ||||

| 15-20 (SC) | 60 (SC) | 3-4(SC) | ||||

| 15-20 (IM) | 60 (IM) | 3-4 (IM) | ||||

2. Starting IV PCA prescription ranges for opioid-naïve adults (Table 26-2)

| IV, Intravenous; NR, not recommended; PCA, patient-controlled analgesia; PRN, as needed. | ||||||

| *To save time and prevent errors, tables with PCA prescription ranges commonly used for opioid-naïve patients with severe, moderate, and mild pain can be developed in advance. This table is an example for severe pain. Ranges for moderate pain are 50% of those for severe pain, for mild pain 25%. |

||||||

| †Should be used for very brief course, in patients who are allergic to the other opioids listed in this chart. |

||||||

| ‡Accumulation of normeperidine can cause toxic CNS effects and is more likely to occur when meperidine is administered by continuous infusion. |

||||||

| From McCaffery M, Pasero C: Pain: Clinical manual, ed 2, St Louis, 1999, Mosby. Data from American Pain Society (APS): Principles of analgesic use in the treatment of acute and cancer pain, ed 3, Glenview, IL, 1992, APS; and Hunt RF, Abbott Laboratories, Hospital Products Division: Letter communication to Malcolm Cohen, MD, Mt. Sinai Medical Center, Miami Beach, FL, July 11, 1989. | ||||||

| Drug | Typical Concentration | Loading Dose | PCA Dose | Delay | Basal Rate | Hour Limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphine | 1 mg/mL | 2.5 mg, repeat PRN | 0.6-2.0 mg | 5-10 min | 0-1.25 mg/h | 7.5-12.5 mg/h |

| Hydromorphone | 0.2 mg/mL | 0.4 mg, repeat PRN | 0.1-0.3 mg | 5-10 min | 0-0.2 mg/h | 1.2-2.0 mg/h |

| Fentanyl | 10 mcg/mL | 25 mcg, repeat PRN | 5-20 mcg | 4-8 min | 0-10 mcg/h | 75-125 mcg/h |

| Meperidine† | 10 mg/mL | 20 mg, repeat PRN | 5-20 mg | 5-10 min | 0-10 mg/h‡ NR | 50-100 mg/h |

3. Pediatric IV PCA dosing (Table 26-3)

| IV, Intravenous; PCA, patient-controlled analgesia. | |||

| Opioid Analgesic | PCA Dose | Delay (Lock-Out) | Basal Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphine | 10-30 mcg/kg/dose | 6-10 min | 0-30 mcg/kg/h |

| Fentanyl | 0.5-1.0 mcg/kg/dose | 6-10 min | 0-1.0 mcg/kg/h |

| Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) | 3-5 mcg/kg/dose | 6-10 min | 0-5 mcg/kg/h |

4. Managing opioid-induced side effects

a. Constipation

(1) Stool softener

(2) Rectal exam to rule out impaction

(3) Disimpaction—administer rescue analgesia or tranquilizer before procedure.

b. Nausea and vomiting

(1) Titrate opioid doses slowly and steadily.

(2) Add or increase nonopioid or adjuvant for additional pain relief.

(3) Antiemetic

(4) Support use of relaxation techniques.

c. Pruritus

(1) Reduce opioid by 25% if analgesia satisfactory.

(2) Add or increase nonopioid or nonsedating adjuvant for additional pain relief.

(3) Benadryl

(4) Naloxone as a last resource

d. Mental confusion

(1) Evaluate underlying cause.

(2) Eliminate nonessential CNS-acting medications (e.g., steroids).

(3) Reduce opioid by 25% if analgesia satisfactory.

(4) Reevaluate and treat underlying process.

(5) If delirium persists:

(a) Switch to another opioid.

(b) Switch to intraspinal route.

(6) Avoid naloxone.

e. Sedation

(1) Evaluate if related to sedation from opioid.

(2) Eliminate nonessential CNS depressant medications.

(3) Reduce opioid by 1% to 25% if analgesia satisfactory.

(4) Add or increase nonopioid or nonsedating adjuvant for additional pain relief.

(5) Add stimulus during the day (e.g., caffeine).

f. Respiratory depression

(1) Monitor sedation level and respiratory rate.

(2) Add or increase nonopioid or nonsedating adjuvants.

(3) Decrease opioid by 25% if analgesia satisfactory.

(4) Stop opioid if patient minimally responsive.

J. Nonpharmacological and integrative therapies

1. Cutaneous stimulation

a. Definition: stimulation of skin by such methods

(1) Heat

(2) Cold

(3) Vibration

b. Potential benefits: range from making pain more tolerable to actual reduction of pain

c. A simple touch can be experienced as a therapeutic gesture of caring.

d. Touch modalities gaining popularity among patients who choose integrative therapies

2. Types

a. Cold therapy

(1) Cold tends to relieve pain faster and longer.

(2) It decreases bleeding and edema.

(3) Apply to site using:

(a) Waterproof bag with ice

(b) Conventional cold pack

(c) Commercial cold therapy device

(d) Effective for:

(i) Surgical incisions

(ii) Headache

(iii) Muscle spasms

(iv) Low back pain

(4) Avoid tissue damage by providing appropriate protective covering.

(5) Inspect skin to assess for potential tissue damage.

b. Heat therapy

(1) Heat therapy may be useful in the following types of pain:

(a) Muscle aches

(b) Spasms

(c) Low back pain

(2) Avoid tissue damage by providing appropriate protective covering.

(3) Inspect skin for potential tissue damage.

c. Vibration

(1) A form of an electric massage

(2) Has a soothing effect

(3) Vibration with moderate pressure may relieve pain by causing:

(a) Numbness

(b) Paresthesia

(c) Anesthesia

(4) May change character of sensation from sharp to dull

(5) Handheld and stationary vibrators can be used.

d. Touch modalities

(1) Reiki techniques

(a) Originated nearly 3000 years ago and is believed to balance energy and bring harmony to:

(i) Body

(ii) Mind

(iii) Soul

(b) Usually performed by a trained Reiki master

(c) Technique involves light touch over clothing.

(i) Begin with the head.

(ii) Work down the body front and back.

(d) Helpful in reducing stress and anxiety

(e) Promotes relaxation

(2) Therapeutic touch

(a) Introduced in 1979

(i) Unlike laying-on of hands

(ii) Does not require physical touch

(iii) Name can be misleading

(b) Practitioners believe:

(i) Human beings are open energy systems.

(ii) Flow of energy between people is a natural and continuous event.

(c) Practitioner uses self to facilitate healing that occurs during the treatment.

(d) Provides:

(i) Calming response

(ii) Decreased anxiety

(iii) Promotes sleep when used alone or with sedatives

(e) Since physical touch not necessary when doing therapeutic touch, it can ideally be used in patients for whom touch would be painful.

3. Relaxation techniques

a. Definition: relaxation is a state of relative freedom from both anxiety and skeletal muscle tension.

b. Benefits

(1) Not a substitute for appropriate pain management

(2) May reduce anxiety

(3) Decrease muscle tension

(4) Promote the ability to sleep

c. More beneficial when patient:

(1) Receives preoperative instructions to practice relaxation techniques

(2) Coached to use during postoperative phase

d. Researchers suggest a 20-minute technique be used three times a day for maximum stress-reducing response.

e. Types

(1) Slow deep breathing

(a) Clench fists.

(b) Breathe in deeply.

(c) Hold breath a moment.

(d) Breathe out.

(e) Let oneself go limp.

(f) Start yawning.

(2) Imagery: effective approach to relaxation that reduces pain intensity

(a) Involves closing one’s eyes to recall:

(i) Pleasant or peaceful experiences

(ii) Calming places or events

(3) Superficial massage

(a) Handholding

(b) Rubbing a shoulder

(c) Rhythmic application of pressure to skin and muscles

(d) Techniques may:

(i) Decrease pain

(ii) Relax muscles

(iii) Facilitate sleep

(e) Must obtain patient’s permission to be touched

(f) Common areas for massage include:

(i) Back and shoulders

(ii) Hand

(iii) Feet

(g) Can communicate care and concern when verbal interactions are limited

(4) Music therapy

(a) Learn to use music for:

(i) Distraction

(ii) Relaxation

(b) Researchers found that patients who listen to music may have more satisfying hospital experiences.

(c) Use soothing background music in preoperative area.

(d) Small, portable tape players with headsets help block out extraneous noises and promote relaxation.

(e) Establish a tape library with available music selections and relaxation tapes.

(f) Encourage patient to request personal preferences.

4. Distraction

a. Definition: sometimes referred to as cognitive refocusing; attention and concentration directed at stimuli other than pain

b. Benefits: although the effects as a method of pain management are unpredictable, it may:

(1) Decrease intensity of pain.

(2) Increase pain tolerance.

(3) Make more acceptable pain sensation.

(4) Improve positive mood.

c. Often beneficial in mild to moderate pain associated with a procedure

(1) Peripheral IV insertion

(2) Repositioning

d. Distraction used more effectively before pain actually begins

(1) Types

(a) Music

(b) Video games

(c) Imagery

(d) Prayer

(e) Aromatherapy

(f) Hypnotherapy

(g) Humor

5. Nonpharmacological approaches to pain management for children

a. Distraction

(1) Involve parent and child in identifying strong distractions.

(2) Involve child in play by:

(a) Using radio

(b) Tape recorder

(c) Record player

(d) Having child sing

(e) Using rhythmic breathing

(3) Have child take a deep breath and blow it out until told to stop.

(4) Have child blow bubbles to “blow the hurt away.”

(5) Have child concentrate on yelling or saying “ouch” by focusing on “yelling loud or soft as you feel it hurt; that way I know what’s happening.”

(6) Have child look through kaleidoscope and concentrate on the different designs.

(7) Use humor: watch cartoons, tell jokes or funny stories, or act silly.

(8) Have child read, play games, or visit with friends.

b. Relaxation

(1) Hold in a comfortable, well-supported position, such as vertical against chest and shoulder.

(2) Rock in a chair.

(3) Repeat one or two words softly: “Mommy’s here.”

(4) Ask child to take a deep breath and go limp like a rag doll.

(5) Suggest child float like a balloon.

c. Imagery for distraction or relaxation

(1) Have child identify some highly pleasurable stories or pretend experiences.

(2) Have child describe details of the events.

(3) Have child write down or record script.

(4) Encourage child to concentrate on pleasurable events during painful time.

d. Cutaneous stimulation

(1) Rhythmic rubbing

(2) Pressure

(3) Electric vibrator

(4) Massage with hand lotion.

(5) Powder or menthol cream

(6) Application of heat and cold on site before giving injection

(7) Application of ice to site opposite painful area

II. COMFORT

A. Definition: the immediate experience of being strengthened by having a need for relief, ease, and transcendence met in four contexts

1. Physical

2. Psychospiritual

3. Sociocultural

4. Environmental

B. Context of comfort

1. Physical—pertaining to bodily sensations and homeostatic mechanisms that may or may not be related to specific diagnoses

2. Psychospiritual—whatever gave life meaning for an individual and entailed:

a. Self-esteem

b. Self-concept

c. Sexuality

d. Relationship to a higher order or being

3. Sociocultural—pertaining to interpersonal, family, and societal relationships including:

a. Finances

b. Education

c. Support

(1) Family histories

(2) Traditions

(3) Language

(4) Clothes

(5) Customs

4. Environmental—pertaining to external surroundings, conditions, and influences

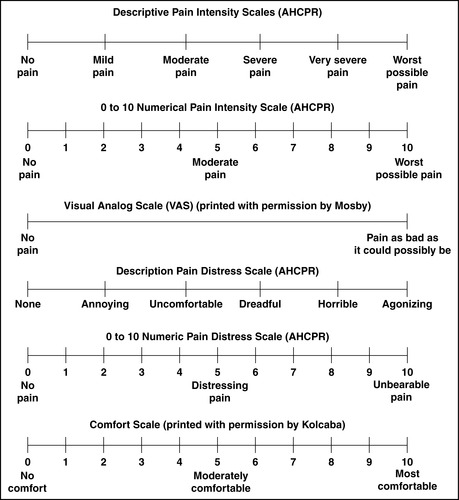

C. Methods for pain and comfort assessment

1. Pain scales (Figures 26-2 and 26-3)

|

| FIGURE 26-2 ▪

Pain scales.

|

|

| FIGURE 26-3 ▪

FACES scale.

(From Wong DL, Hockenberry M, Wilson D, et al: Whaley and Wong’s nursing care of infants and children, ed 7, St Louis, 2003, Mosby. Printed with permission by Elsevier.)

|

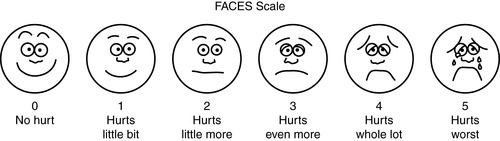

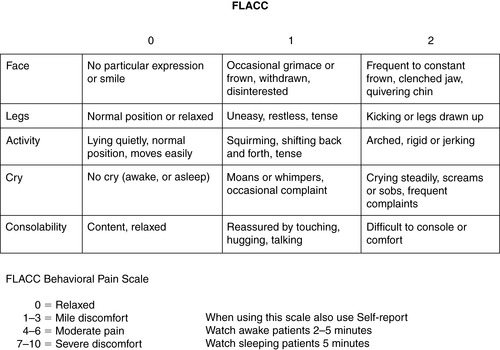

2. FLACC Scale (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability) (Figure 26-4)

|

| FIGURE 26-4 ▪

FLACC Pain Assessment Tool.

(From Merkel S, Voepel-Lewis T, Shayevitz J, et al: The FLACC: A behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children. Pediatr Nurs 23(3):293-297, 1997. With permission of Jannetti Publications, Inc.)

|

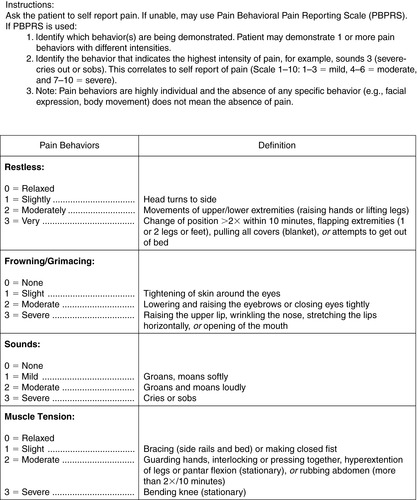

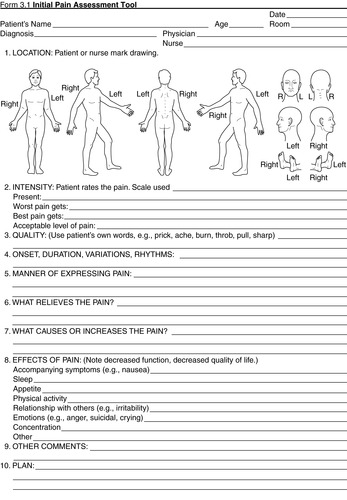

3. PACU Behavioral Pain Rating Scale (Figures 26-5 and 26-6)

|

| FIGURE 26-5 ▪

PACU Pain Behavioral Pain Scale.

(Printed with permission by Johns Hopkins Hospital.)

|

|

| FIGURE 26-6 ▪

Initial Pain Assessment Tool.

(From McCaffery M, Pasero C: Pain: Clinical manual, St Louis, 1999, Mosby.)

|

III. PAIN AND COMFORT MANAGEMENT

A. Preoperative phase—assessment

1. Vital signs including pain and comfort goals (e.g., 0-10 scale)

2. Medical history

a. Neurological status

b. Cardiac and respiratory instability

c. Allergy to medication, food, and objects

d. Use of herbs

e. Motion sickness

f. Sickle cell

g. Fibromyalgia

h. Use of caffeine, substance abuse

i. Fear and anxiety

3. Pain history

a. Preexisting pain

b. Acute, chronic pain level

c. Pattern

d. Quality

e. Type of source

f. Intensity

g. Location

h. Duration and time

i. Course

j. Pain affect

k. Effects on personal life

4. Pain behaviors and expressions or history

a. Grimacing

b. Frowning

c. Crying

d. Restlessness

e. Tension and discomfort behaviors

(1) Shivering

(2) Nausea

(3) Vomiting

f. Note that physical appearance may not necessarily indicate pain and discomfort or their absence.

5. Analgesic history

a. Type

(1) Opioid

(2) Nonopioid

(3) Adjuvant analgesics

b. Dose

c. Frequency

d. Effectiveness

e. Adverse effects

f. Other medications that may influence choice of analgesics

(1) Anticoagulants

(2) Antihypertensives

(3) Muscle relaxants

6. Patient’s preferences for pain relief and comfort measures

a. Expectations

b. Concerns

c. Aggravating and alleviating factors

d. Clarification of misconceptions

7. Pain and comfort acceptable levels

a. Patient and family (as indicated) agree on plan of treatment and interventions postoperatively.

8. Comfort history

a. Physical

(1) Warming measures

(2) Positioning

b. Sociocultural

c. Psychospiritual

(1) Spiritual beliefs and symbols

d. Environment

(1) Music

(2) Comfort objects

(3) Privacy

(4) Factors related to nausea and vomiting

9. Educational needs

a. Consider age or level of education.

b. Cognitive

c. Language appropriateness

d. Barriers to learning

10. Cultural language preference, identification of personal beliefs, and resulting restrictions

11. Pertinent laboratory results in patient with epidural catheter

a. Prolonged prothrombin time (PT)

b. Prolonged partial thromboplastin time (PTT)

c. Abnormal international normalized ratio (INR)

d. Platelet count

B. Preoperative phase—interventions

1. Identify patient.

2. Validate physician’s order and procedure.

a. Correct name of drug, dose, amount, route, and time

b. Validate type of surgery and correct surgical site as applicable.

3. Discuss pain and comfort assessment.

a. Presence

b. Location

c. Quality

d. Intensity

e. Age

f. Language

g. Condition

h. Cognitive appropriate pain rating scale (assessment method must be the same for consistency)

4. Discuss with patient and family information about reporting pain intensity using numerical or FACES rating scales and available pain relief and comfort measures.

a. Include discussion of patient’s preference for pain and comfort measures.

5. Implement comfort measures as indicated by patient.

a. Physiological

b. Sociocultural

c. Spiritual

d. Environmental support

6. Discuss and dispel misconceptions about pain and pain management.

7. Encourage patient to take a preventive approach to pain and discomfort by asking for relief measures before pain and discomfort are severe or out of control.

8. Educate on purpose of IV or epidural PCA as indicated.

9. Educate about use of nonpharmacological methods.

a. Cold therapy

b. Relaxation breathing

c. Music

10. Discuss potential outcomes of pain and discomfort treatment approaches.

11. Establish pain relief and comfort goals with the patient.

a. A pain rating of less than 4 (scale 0–10) to make it easy to:

(1) Cough

(2) Deep breathe

(3) Turn

12. Premedicate patient for sedation, pain relief, comfort.

a. Nonopioid

b. Opioid

c. Antiemetics

d. Consider needs of patient with chronic pain.

13. Arrange interpreter throughout the continuum of care as indicated.

14. Use interventions for sensory-impaired patients.

a. Device to amplify sound

b. Sign language

c. Interpreters

15. Report abnormal findings including laboratory values for patient with epidural catheter.

a. Prolonged PT (>12.5 seconds)

b. PTT (>35 seconds)

c. INR (>5)

d. Platelet (<150,000/mm 3)

16. Arrange for parents to be present for children.

C. Preoperative phase—expected outcomes

1. Patient states understanding of care plan and priority of individualized needs.

2. Patient states understanding of pain intensity scale, comfort scale, and pain relief and comfort goals.

3. Patient establishes realistic and achievable pain relief and comfort goals.

a. A pain rating of less than 4 (scale 0–10) to make it easy to:

(1) Cough

(2) Deep breathe

(3) Repositioning

4. Patient states understanding or demonstrates correct use of PCA equipment as indicated.

5. Patient verbalizes understanding of importance of using other nonpharmacological methods of alleviating pain and discomfort.

a. Cold therapy

b. Relaxation breathing

c. Music

D. Postanesthesia phase I—assessment

1. Refer to preoperative phase assessment, interventions, and outcomes data.

2. Type of surgery and anesthesia technique, anesthetic agents, reversal agents

3. Analgesics

a. Nonopioid

b. Opioid

c. Adjuvants given before and during surgery

d. Last dose time and amount

e. Regional (e.g., spinal and epidural)

4. Pain and comfort levels on admission and until transfer to receiving unit or discharge to home

a. Reassess frequently until pain or discomfort is controlled.

b. Assess continuously during sedation procedure.

5. Assessment parameters

a. Functional level and ability to relax

b. Pain

(1) Type

(2) Location

(3) Intensity

(4) Use self-report pain rating scale whenever possible.

(a) Age

(b) Language

(c) Condition

(d) Cognitively appropriate tools

(i) Quality

(ii) Frequency (continuous or intermittent)

(iii) Sedation level

c. Patient’s method of assessment and reporting needs to be the same during the postoperative continuum of care for consistency.

d. Self-report of comfort level using numerical scale (scale 0–10) or other institutional approved instruments

e. Physical appearance

(1) Pain and discomfort behaviors

(2) Note: pain behaviors are highly individual and the absence of any specific behavior (e.g., facial expression, body movement) does not mean the absence of pain.

f. Other sources of discomfort

(1) Position

(2) Nausea and vomiting

(3) Shivering

(4) Environment

(a) Noise

(b) Noxious smell

6. Achievement of pain relief and comfort treatment goals

7. Age, cognitive ability, and cognitive learning method

8. Status and vital signs

a. Airway patency

b. Respiratory status

c. Breath sounds

d. Level of consciousness

e. Pupil size as indicated

f. Other symptoms related to effects of medications

g. Blood pressure

h. Pulse and cardiac monitor rhythm

i. Oxygen saturation

j. Motor and sensory functions after regional anesthesia technique

E. Postanesthesia phase I—interventions

1. Identify patient correctly.

2. Validate physician’s order.

3. Implement correct name of drug, dose, amount, route, and time.

4. Include type of surgery and surgical site as applicable.

5. Consider multimodal therapy.

6. Pharmacological (as ordered)

a. Mild to moderate pain—use nonopioids.

(1) Acetaminophen

(2) NSAIDs

(3) Cox-2 inhibitors

(4) All the patient’s regular nonopioid prescription medications should be made available unless contraindicated.

(5) May consider opioid

b. Moderate to severe pain

(1) Combine nonopioid and opioid.

c. Use the three analgesic groups appropriately.

(1) Nonopioids

(a) Aspirin

(b) Acetaminophen

(c) NSAIDs

(i) Ketorolac

(ii) Ibuprofen

(d) Cox-2 inhibitors

(2) Mu-agonist opioids

(a) Morphine

(b) Hydromorphone

(c) Fentanyl

(3) Adjuvants

(a) Multipurpose for chronic pain

(i) Anticonvulsants

(ii) Tricyclic antidepressants

(iii) Corticosteroids

(iv) Antianxiety medication

(b) Multipurpose for moderate to severe acute pain

(i) Local anesthetics

(ii) Ketamine, an NMDA receptor blocker (patient education should include telling the patient to expect dreamlike feelings during administration)

(c) Continuous neuropathic pain

(i) Antidepressants

(ii) Tricyclic antidepressants

(iii) Oral or local anesthetic

(d) Lancinating (stabbing, knifelike pain) neuropathic pain

(i) Anticonvulsant

(ii) Baclofen

(e) Malignant bone pain

(i) Corticosteroids

(ii) Calcitonin

(f) Postorthopedic surgery

(i) Consider muscle relaxants if patient experiences muscle spasm.

(4) Initiate and adjust regional infusions (PCA) as indicated and ordered, based on hemodynamics status.

(a) Refer to institutional permissive procedure.

(5) Nonpharmacological interventions—use to complement, not replace, pharmacological interventions.

7. Administer comfort measures as needed.

a. Physical

(1) Positioning

(2) Pillow

(3) Heat and cold therapies

(4) Sensory aids

(a) Dentures

(b) Eye glasses

(c) Hearing aids

(5) Use meperidine (Demerol) for shivering as ordered.

b. Sociocultural

(1) Family and caregiver

(2) Interpreter visit

c. Psychospiritual

(1) Chaplain or cleric of choice

(2) Religious objects and symbols

d. Environmental

(1) Confidentiality

(2) Privacy

(3) Reasonably quiet room

e. Cognitive behavioral

(1) Education and instruction

(2) Relaxation

(3) Imagery

(4) Music

(5) Distraction

(6) Biofeedback

F. Postanesthesia phase I—expected outcomes

1. Patient maintains hemodynamic stability including respiratory and cardiac status and level of consciousness.

2. Patient states achievement of pain relief and comfort treatments goals (e.g., acceptable pain relief with mobility at time of transfer or discharge).

3. Patient feels safe and secure.

4. Patient demonstrates effective use of at least one nonpharmacological method.

a. Breathing relaxation techniques

5. Patient demonstrates effective use of PCA as indicated, and discusses expected results of regional techniques.

6. Patient verbalizes evidence of receding pain level and increased comfort with pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions.

G. Postanesthesia phase II and extended observation—assessment

1. Refer to preoperative phase and phase I assessments, interventions, and outcomes data.

2. Achievement of pain and comfort treatment goals and level of satisfaction with pain relief and comfort management

3. Pain relief and comfort management plan for discharge and patient agreement

4. Educational and resource needs, considering age, language, condition, and cognitive appropriateness

H. Postanesthesia phase II and extended observation—interventions

1. Identify patient correctly.

2. Validate physician’s order.

3. Implement correct name of medication, dose, amount, route, and time.

4. Pharmacological interventions (as ordered)

a. Nonopioid

(1) Acetaminophen

(2) NSAIDs

(3) Cox-2 inhibitors

b. Mu-agonist opioids

(1) Morphine

(2) Hydromorphone

(3) Fentanyl

c. Adjuvant analgesics

(1) Local anesthetics

5. Continue and/or initiate nonpharmacological measures from phase I.

6. Educate patient, family, and caregiver.

a. Pain and comfort measures

b. Untoward symptoms to observe

c. Regional or local anesthetic effects dissipating after discharge

(1) Numbness

(2) Motor weakness

(3) Inadequate relief

7. Discuss misconceptions and expectations, and implement plan of action satisfactory to patient.

8. Address nausea with pharmacological interventions or other techniques and discuss expectations.

I. Postanesthesia phase II and extended observation—expected outcomes

1. Patient states acceptable level of pain relief and comfort with movement or activity at time of transfer or discharge to home.

2. Patient verbalizes understanding of discharge instruction plans.

a. Specific medication to be taken

b. Frequency of medication administration

c. Potential side effects of medication

d. Potential adjustments as applicable

e. Potential medication interactions

f. Specific precaution to follow when taking medication

(1) Physical limitation

(2) Dietary restrictions

g. Name and telephone number of physician or resource to notify about pain, problems, and other concerns

3. Patient states understanding or demonstrates effective use of nonpharmacological methods.

a. Cold and heat therapy

b. Relaxation breathing

c. Imagery

d. Music

4. Patient states achievement of pain and comfort treatment goals and level of satisfaction with pain relief and comfort management in perianesthesia setting.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. American Society for Pain Management Nursing, Pain management nursing: Scope and standards of practice. ( 2005)Nursesbooks, Silver Spring, MD.

2. American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses, Standards of perianesthesia nursing practice 2008–2010. ( 2008)ASPAN, Cherry Hill, NJ.

3. Ballantyne, J., The Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of pain management. ( 2006)Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.

4. Bayley, E.; Turcke, S., A comprehensive curriculum for trauma nursing. ( 1998)Roadrunner Press, Park Ridge, IL.

5. Burden, N.; Quinn, D.; O’Brien, D.; et al., Ambulatory surgical nursing. ed 2 ( 2000)Saunders, Philadelphia.

6. Cole, D.; Schlunt, M., Adult perioperative anesthesia. ( 2004)Mosby, St Louis.

7. Drain, C.; Odom-Forren, J., Perianesthesia nursing: A critical care approach. ed 5 ( 2009)Saunders, Philadelphia.

8. Dunwoody, C.; Krenzischek, D.; Pasero, C.; et al., Assessment, physiological monitoring and consequences of inadequately treated acute pain, J Perianesth Nurs 23 (Suppl 1) ( 2008) S15–S27.

9. Kolcaba, K., Comfort theory and practice: A vision for holistic health care and research. ( 2003)Springer, Philadelphia.

10. Kolcaba, K.Y., A taxonomic structure for the concept of comfort, Image J Nurs Sch 23 (4) ( 1991) 237–240.

11. Kolcaba, K.Y., Holistic comfort: Operationalizing the construct as a nurse sensitive outcome, ANS Adv Nurs Sci 15 (1) ( 1992) 1–10.

12. Kolcaba, K.Y., A theory of holistic comfort for nursing, J Adv Nurs 19 (6) ( 1994) 1178–1184.

13. Kolcaba, K.Y., The comfort line website, Available at:www.thecomfortline.com/index.html; Accessed August 25, 2008.

14. Kolcaba, K.; DiMarco, M., Comfort theory and its application to pediatric nursing, Pediatr Nurs 31 (3) ( 2005) 187–194.

15. Kolcaba, K.; Dowd; Steiner, R., : Development of an instrument to measure holistic client comfort as an outcome of healing touch, Holist Nurs Pract 20 (2006) 122–129.

16. Kolcaba, K.; Schirm, V.; Steiner, R., Effects of hand massage on comfort of nursing home residents, Geriatr Nurs 27 (2) ( 2006) 85–91.

17. Kolcaba, K.; Tilton, C.; Drouin, C., Comfort theory: A unifying framework to enhance the practice environment, J Nurs Adm 36 (11) ( 2006) 538–544.

18. Kolcaba, K.; Wilson, L., Comfort care: A framework for perianesthesia nursing, J Perianesth Nurs 17 (2) ( 2002) 102–111; quiz 111–113.

19. Krenzischek, D.; Wilson, L., An introduction to the ASPAN pain and comfort clinical guideline, J Perianesth Nurs 18 (4) ( 2003) 228–236.

20. Loeser, J., Bonica’s management of pain. ed 3 ( 2001)Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.

21. McCaffery, M.; Pasero, C., Pain: Clinical manual. ( 1999)Mosby, St Louis.

22. Merkel, S.; Shobha, M., Pediatric pain: Tools and assessment, J Perianesth Nurs 15 (6) ( 2000) 408–414.

23. Merkel, S.; Voepel-Lewis, T.; Shayevitz, J.; et al., The FLACC: A behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children, Pediatr Nurs 23 (3) ( 1997) 293–297.

24. Pasero, C., Fentanyl for acute pain management, J Perianesth Nurs 20 (4) ( 2005) 279–284.

25. Pasero, C., Procedure specific pain management: PROSPECT, J Perianesth Nurs 22 (5) ( 2007) 335–340.

26. Pasero, C., The registered nurse’s role in the management of analgesia by catheter technique, J Perianesth Nurs 23 (1) ( 2008) 53–56.

27. Pasero, C.; McCaffery, M., Orthopaedic postoperative pain management, J Perianesth Nurs 22 (3) ( 2007) 160–172; quiz 172–173.

28. Sibell, D.; Kirsch, J., The 5 minute pain management consult. ( 2006)Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.

29. Wardwell, D.W.; Engebretson, J., Biological correlates of Reiki touch healing, J Adv Nurs 33 (4) ( 2001) 439–445.

30. Wilson, L.; Kolcaba, K., Practical application of comfort theory in the perianesthesia setting, J Perianesth Nurs 19 (3) ( 2004) 164–173.