Emergency Medicine and the Law

Edited by George Jelinek

25.1 Mental health and the law: the Australasian and UK perspectives

Georgina Phillips, Suzanne Mason and Simon Baston

Introduction

The emergency department (ED) is frequently the interface between the community and the mental health system. In recent years, changes in health policy have resulted in ‘mainstreaming’ of mental health services, so that stand-alone psychiatric services are less common and services are more likely to be provided in a general hospital setting. Linked to this has been a move away from managing long-term psychiatric patients in institutional settings, so that many of these former patients are now living in the community with or without support from mental health services.

Traditionally, by virtue of their accessibility, EDs have been a point of access to mental health services for persons with acute psychiatric illness, whether this be self- or family referral or by referral from ambulance, police or outside medical practitioners. An important function of an ED is to differentiate between those who require psychiatric care for a psychiatric illness and those who present with a psychiatric manifestation of a physical illness and who require medical care. Admission of a patient with a psychiatric manifestation of a physical illness to a psychiatric unit may result in further harm to or death of the patient.

In the UK and Australasia, doctors in general are empowered by legislation to detain a mentally ill person who is in need of treatment. Mental illness, particularly its manifestation as self-harm, is a common ED presentation (in the UK, making up around 1–2% of new patient attendances and up to 5% of attendances in Australasia) and emergency physicians require not only the clinical skills to distinguish between those who require psychiatric or medical intervention, but also a sound working knowledge of the mental health legislation and services relevant to the state where they practise. This ensures that patients with psychiatric illness are managed in the most appropriate way, with optimal utilization of mental health resources and with the best interests and rights of the patient and the community taken into consideration.

While there are variations in mental health legislation between the UK, Australia and New Zealand, all legislation recognizes fundamental common principles that respect individual autonomy and employ least restrictive management practices. The World Health Organization (WHO) advises 10 basic principles of mental healthcare law, including enshrining geographical, cultural and economic equity of access to mental health care, acceptable standards of clinical assessment, facilitating self-determination, minimizing restrictive treatment and enshrining regular and impartial decision making and review of care [1]. These themes are all present in Australasian and UK law and awareness of such principles aids the clinician in delivering humane and ethical treatment for mentally unwell patients who seek emergency care.

Variations in practice

Mental health legislation in England and Wales

The National Service Framework for Mental Health

The National Service Framework for Mental Health produced by the Department of Health in the UK (1999) is aimed at improving quality and addresses the mental health needs of working age adults up to 65 years. It states as one of its standards that:

Any individual with a common mental health problem should be able to make contact round the clock with the local services necessary to meet their needs and receive adequate care.

Although EDs do not provide the ideal environment for a mental health assessment, they are likely to continue to provide an entry point for people with mental health problems. Easy access to the ED can lead to individuals with acute mental health problems seeking help directly, making up to perhaps 5% of ED attenders.

Two pieces of legislation cover the care and treatment of patients with disorders of the brain or mind. The Mental Health Act (1983) deals with compulsory assessment and treatment of people with mental illnesses, while the Mental Capacity Act (2005) deals with people who are unable to make decisions about their medical treatment for themselves for various reasons.

Mental Health Act

Definition of mentally ill or mental illness

According to the 1983 Mental Health Act, mental illness is undefined. However, in practice it includes conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, psychosis and organic brain syndromes. Mental impairment is defined as: ‘a state of arrested or incomplete development of mind which includes significant impairment of intelligence and social functioning and is associated with abnormally aggressive or seriously irresponsible conduct on the part of the person concerned’. A psychopathic disorder is defined as ‘a persistent disorder or disability of mind which results in abnormally aggressive or seriously irresponsible conduct on the part of the person concerned’. The Act does not cover promiscuity or other immoral conduct or sexual deviancy which, in the past, could result in incarceration in psychiatric hospitals or dependence on drugs or alcohol.

Detention of patients with mental illness

The Mental Health Act 1983 provides legislation with regard to the management of patients with a mental illness unwilling to be admitted or detained in hospital voluntarily, where this would be in the best interests of the health and safety of patients and others. For the purposes of the Act, patients in the ED are not considered inpatients until they are admitted to a ward. In order for legislation to be imposed, it is necessary for two conditions to be satisfied: the patient must be suffering from a mental illness and emergency hospital admission is required because the patient is considered to be a danger to themselves or others.

Detention under the Mental Health Act does not permit treatment for psychiatric or physical illness. Treatment can be given under common law where the patient is considered to pose a serious threat to themselves or others. Otherwise all treatment must be with the patient’s consent.

Section 2 of the Mental Health Act facilitates compulsory admission to hospital for assessment and treatment for up to 28 days. The application is usually made by an approved social worker or the patient’s nearest relative and requires two medical recommendations, usually from the patient’s general practitioner and the duty senior psychiatrist (who is approved under Section 12 of the Mental Health Act). In the ED, the responsibility for coordinating the procedure often lies with the emergency physician.

Section 3 of the Mental Health Act covers compulsory admission for treatment. Once again, recommendations must be made by two doctors, one of whom is usually the general practitioner and the other a psychiatrist approved under Section 12 of the Act. The application is usually made by an approved social worker or the patient’s nearest relative. Detention is for up to 6 months but can be renewed.

Section 4 of the Mental Health Act covers emergency admission for assessment and attempts to avoid delay in emergency situations when obtaining a second recommendation could be dangerous. It requires the recommendation of only one doctor, who may be any registered medical practitioner who must have seen the patient within the previous 24 h. The order lasts for 72 h. Application can be made by the patient’s nearest relative or an approved social worker. In practice, the application of Section 4 of the Mental Health Act rarely happens. Usually Section 2 or 3 is the preferred option.

Section 5(2) – doctors holding power and Section 5(4) – nurses holding power of the Act allow the detention of patients who are already admitted to hospital until a more formal Mental Health Act assessment can take place. Unfortunately, presence in the ED is not considered to constitute admission to hospital and this section is, therefore, not applicable to the ED.

A new draft Mental Health Bill, published in 2002, was opposed by professional and patient groups alike. It aimed to introduce a new legal framework for the compulsory treatment of people with mental disorders in hospitals and the community. The new procedure involved a single pathway in three stages: a preliminary examination, a period of formal assessment lasting up to 28 days and treatment under a Mental Health Act order. In order for the compulsory process to be used, four conditions needed to be satisfied: the patient must have a mental disorder, the disorder must warrant medical treatment, treatment must be necessary for the health and safety of the patient or others, and an appropriate treatment for the disorder must be available. The draft Bill made provision for treatment without consent as it is justified under the European Convention on Human Rights Article 8(2) in the interests of public safety or to protect health or moral standards.

The resulting debate saw much of the draft Bill being scrapped in favour of amendments being made to the existing Mental Health Act. This included the creation of community treatment orders and a broader definition of mental disorder.

Police powers

Section 136 of the Act authorizes the police to remove patients who are believed to be mentally disordered and causing a public disturbance to a place of safety. The place of safety referred to in the Act is defined in Section 135 as ‘residential accommodation provided by a local authority under Part III of the National Assistance Act 1948, or under Paragraph 2, Schedule 8 of the National Health Service Act 1977, a hospital as defined by this Act, a police station, a mental nursing home or residential home for mentally disordered persons or any other suitable place, the occupier of which is willing temporarily to receive the patient’. In practice, the police often transport these patients to local EDs. The patient must be assessed by an approved social worker and a registered doctor. The order lasts for 72 h.

Section 135 allows the police to enter premises to remove a patient believed to be suffering from a mental disorder to a place of safety for up to 72 h. The patient is then assessed as above.

Mental Capacity Act

The Mental Capacity Act relates to decision making, for those whose mental capacity is in doubt, on any issue from what to wear to the more difficult issues of medical treatment, personal finance and housing.

Lack of capacity can occur in two distinct ways. First, that capacity is never achieved – for example someone with a severe learning difficulty. Secondly, capacity can be lost either as a result of long-term conditions, such as dementia, or for a short period because of a temporary factor, such as intoxication, shock, pain or emotional distress.

It is also important that decision making is task specific. An individual may be able to make decisions about simple matters, such as what to eat or wear, but may be unable to make more complex decisions, for example about medical care.

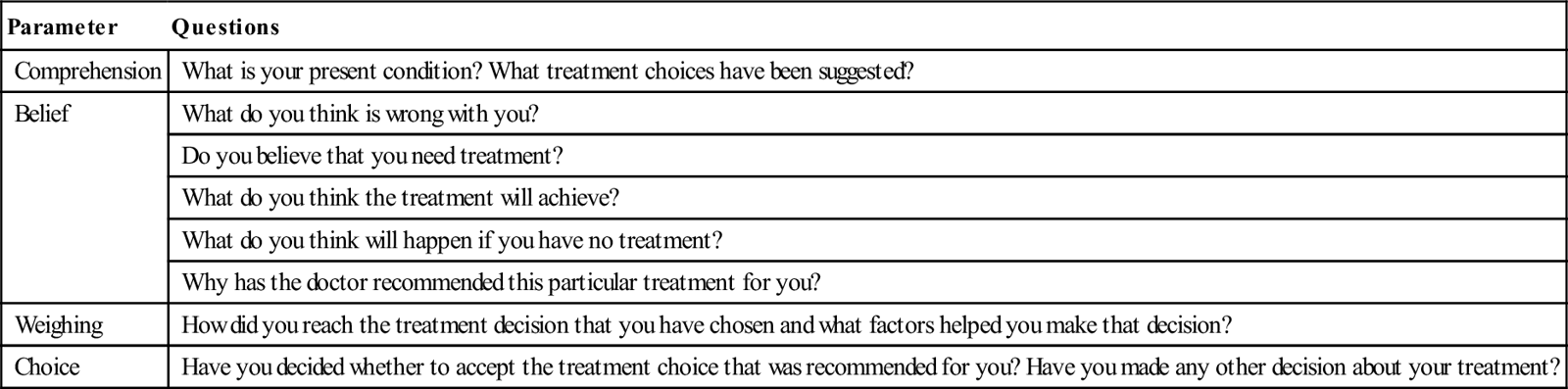

Assessment of capacity

To have capacity about a decision, the patient should be able to comply with the following four steps:

understand the information relevant to the decision

understand the information relevant to the decision

retain the information for the period of decision making

retain the information for the period of decision making

use or weigh that information as part of the process of making a decision

use or weigh that information as part of the process of making a decision

Every effort needs to be made to enable people to make their own decisions.

The Act points out that people should be allowed to make ‘eccentric’ or ‘unwise’ decisions, as it is their ability to decide that is the issue not the decision itself.

Advance directives

The Act makes provision for advance directives to be made at a time when the patient has capacity. These directives need to make specific reference to the medical treatments involved and include the statement ‘even if life is at risk’. The validity of any advance decision needs to be clearly documented.

Advocates

Although family and friends have no legal powers (unless specified in advance) to make decisions for the incapacitated patient, the Act recognizes their role in acting as an advocate. An independent mental capacity advocate is available to represent those with no close family or friends.

Emergency treatment

Treatment can be given to patients who lack capacity but several factors need to be considered:

Use of sedation or physical restraint

This is covered in detail elsewhere (Chapters 20.6 and 21.5). From the perspective of the mental health legislation, there are occasions where physical or pharmacological restraint is needed. Sedation or restraint must be the minimum that is necessary to prevent the patient from self-harming or harming others. Generally, a patient committed involuntarily is subject to treatment necessary for their care and control and this may reasonably include the administration of sedative or antipsychotic medication as emergency treatment. Transporting these patients to a mental health service should be done by suitably trained medical or ambulance staff and not delegated to police officers or other persons acting alone.

Mental health legislation in Australasia

In Australia, mental health legislation is a state jurisdiction and, among the various states and territories, there is considerable variation in the scope of mental health acts and between definitions and applications of the various sections. Since the National Mental Health Strategy in 1992, there has been an effort in Australia to adopt a consistent approach between jurisdictions, with an emphasis on ensuring legislated review mechanisms and a broad spectrum of treatment modalities [2]. In 2009, this national strategic approach was reaffirmed by all the States and Territories of Australia with the release of a National Mental Health Plan, focusing on promoting mental health and preventing mental disorders, minimizing the impact of mental illness across the whole community and protecting the rights of people with mental illness.

Several Australian states and territories have recently initiated mental health law reform, all within a human rights framework. Generally, there is an increased recognition of autonomous and supported decision making with a particular focus on enhancing informed consent through advance directives or involving a nominated support person. Increased transparency of and limitations around restrictive practices will affect activities within EDs. Community visitors and mental health tribunals are introduced to ensure frequent independent oversight and review and it is now mandatory in several jurisdictions to give patients and carers written copies of involuntary orders made about them, as well as a statement of their rights. Despite these common themes, key differences apply between mental health acts and therefore specific issues should be referred to the Act relevant to the emergency physician’s practice location.

The Australian and New Zealand mental health acts and related documents referred to in this chapter are the following:

ACT – Mental Health (Treatment and Care) Act 1994, amendments 2007 and current review documents 2012

Queensland – Mental Health Act 2000

Tasmania – Mental Health Act 1996 and the new Mental Health Bill introduced 2012

Sections of the various mental health acts relevant to emergency medicine include those dealing with:

the definition of mentally ill

the definition of mentally ill

indigenous and cultural acknowledgement

indigenous and cultural acknowledgement

the effects of drugs or alcohol

the effects of drugs or alcohol

criteria for detention and admission as an involuntary patient

criteria for detention and admission as an involuntary patient

persons unable to recommend a patient for involuntary admission

persons unable to recommend a patient for involuntary admission

physical restraint and sedation

physical restraint and sedation

offences in relation to documents

offences in relation to documents

Definition of mentally ill or mental illness

For the purposes of their respective mental health acts, New Zealand and all the Australian states and territories define mental illness or disorder as follows.

Australian Capital Territory

The Australian Capital Territory (ACT) Act defines a psychiatric illness as a condition that seriously impairs (either temporarily or permanently) the mental functioning of a person and is characterized by the presence in the person of any of the following symptoms: delusions, hallucinations, serious disorder of thought form, a severe disturbance of mood or sustained or repeated irrational behaviour indicating the presence of these symptoms.

The ACT Mental Health Act also defines ‘mental dysfunction’ as a ‘disturbance or defect, to a substantially disabling degree, of perceptual interpretation, comprehension, reasoning, learning, judgement, memory, motivation or emotion’.

New South Wales

The New South Wales Act defines mental illness in the same way as the ACT but, in addition, distinguishes between a mentally ill person and a mentally disordered person, chiefly for the purposes of determining need for involuntary admission and treatment.

A person (whether or not the person is suffering from mental illness) is mentally disordered if the person’s behaviour for the time being is so irrational as to justify conclusion on reasonable grounds that temporary care, treatment or control of the person is necessary for the person’s own protection from serious physical harm or for the protection of others from serious physical harm.

New Zealand

In New Zealand, the Mental Health Act defines a mentally disordered person as possessing an abnormal state of mind, whether continuous or intermittent, characterized by delusions or by disorders of mood, perception, volition or cognition to such a degree that it poses a danger to the health or safety of the person or others, or seriously diminishes the capacity of the person to take care of themselves.

Northern Territory

In the Northern Territory, mental illness means a condition that seriously impairs, either temporarily or permanently, the mental functioning of a person in one or more of the areas of thought, mood, volition, perception, orientation or memory and is characterized by the presence of at least one of the following symptoms: delusions, hallucinations, serious disorders of the stream of thought, serious disorders of thought form or serious disturbances of mood. A mental illness is also characterized by sustained or repeated irrational behaviour that may be taken to indicate the presence of at least one of the symptoms mentioned above. The Northern Territory Act goes further to specify that the determination of mental illness is only to be made in accordance with internationally accepted clinical standards.

Similar to the New South Wales Act, there is a provision in the Northern Territory for those who are ‘mentally disturbed’, which means behaviour of a person that is so irrational as to justify the person being temporarily detained under the Act. The Northern Territory also has provisions for people with complex cognitive impairment who require involuntary treatment.

Queensland

The Queensland Act defines mental illness in a similar way to Victoria, in that it is a condition characterized by a clinically significant disturbance of thought, mood, perception or memory, in accordance with internationally acceptable standards.

South Australia

In the South Australian Act, mental illness means any illness or disorder of the mind.

Tasmania

A person is taken to have a mental illness if they experience temporarily, repeatedly or continuously, a serious impairment of thought (which may include delusions) or a serious impairment of mood, volition, perception or cognition.

Victoria

A person is mentally ill if they have a mental illness, being a medical condition characterized by a significant disturbance of thought, mood, perception or memory.

Western Australia

Persons have a mental illness if they suffer from a disturbance of thought, mood, volition, perception, orientation or memory that impairs judgement or behaviour to a significant extent.

Indigenous and cultural acknowledgement

Cultural differences in the understanding and experiences of mental illness can impact greatly on the ability to provide adequate care. While there are some cursory references to acknowledging special cultural and linguistic needs when interpreting the various mental health acts, only the Northern Territory and South Australia in Australia and the New Zealand Mental Health Acts make specific mention of indigenous people, who are known to be a particularly vulnerable group [3]. Recent legislative reform in some Australian states incorporates recognition of the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and other culturally diverse peoples within a general statement of principles.

The Northern Territory Act states that there are fundamental principles to be taken into account when caring for Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. Treatment and care needs to be appropriate to the cultural beliefs and practices of the person, their family and community and involuntary treatment for an Aborigine is to be provided in collaboration with an Aboriginal health worker.

New Zealand stipulates that powers are to be exercised in relation to the Mental Health Act with proper respect for cultural identity and personal beliefs and with proper recognition of the importance and significance to the persons of their ties with family, whanau, hapu, iwi and family group. Interpreters are to be provided if the first or preferred language is not English, with special mention of Maori and New Zealand Sign Language.

Safeguards against prejudice

New Zealand and all Australian states include a number of criteria that, alone, cannot be used to determine that a person has a mental illness and requires involuntary admission. These generally include the expression of or refusal to express particular religious, political and philosophical beliefs; cultural or racial origin; sexual promiscuity or preference; intellectual disability; drug or alcohol taking; economic or social status; immoral or indecent conduct; illegal conduct; and antisocial behaviour. The Northern Territory, Western Australia and Queensland also include past treatment for mental illness and past involuntary admission under these criteria.

Effects of drugs or alcohol

In most Australian states and New Zealand, the taking of drugs or alcohol cannot, of itself, be taken as an indication of mental illness. However, the mental health acts of New South Wales, South Australia, Tasmania, Western Australia and Victoria specify that this does not prevent the serious temporary or permanent physiological, biochemical or psychological effects of alcohol or drug taking from being regarded as an indication that a person is mentally ill. The Queensland Act acknowledges that a person may have a mental illness caused by taking drugs or alcohol.

The remaining states do not specifically exclude the temporary or permanent effects of drugs or alcohol but use definitions of mental or psychiatric illness that are broad enough to cover this. Generally, when a person is so mentally and behaviourally disordered as a result of drug or alcohol use that adequate assessment is impossible and risk of harm to self or others is high, then detaining them for the purposes of assessment and treatment is possible under all Australian and New Zealand mental health acts.

Criteria for admission and detention as an involuntary patient

All states require that an involuntary patient has a mental illness that requires urgent treatment while detained in an inpatient setting for the health (mental or physical) and safety of that patient or for the protection of others. Most states also require that the patient has refused or is unable to consent to voluntary admission. It is also emphasized that appropriate treatment must be available and cannot be given in a less restrictive setting. In New South Wales, the effects of chronicity and the likely deterioration of the person’s condition should be taken into account when determining need for involuntary admission.

Western Australia includes the protection of the patient from self-inflicted harm to the patient’s reputation, relationships or finances as grounds for involuntary admission, although future legislation is likely to remove this criterion.

In New Zealand, the doctor must have reasonable grounds for believing that the person may be mentally disordered and that it is desirable, in the interests of the person, or of any other person or of the public, that assessment, examination and treatment of the person are conducted as a matter of urgency.

Involuntary admission

The process of involuntary admission varies quite markedly across the states. It is variously known as recommendation, certification or committal. All jurisdictions require doctors to examine patients and carefully document on prescribed forms the date and time of examination as well as the particular reasons why the doctor believes that the person has a mental illness that requires involuntary treatment. In addition, patients or their advocates are to be informed of the decisions made about them and their rights under the law at all stages of the involuntary admission process. Increasingly, clinicians are required to give copies of formal orders and printed information about their rights to patients and guardians.

ACT

In the ACT, a medical or police officer is able to apprehend a mentally ill person who requires involuntary admission and is able to use reasonable force and enter premises in order to do so. The officer is required, as soon as possible, to provide a written statement to the person in charge of the mental health facility giving patient details and the reasons for taking the action.

A doctor employed by the mental health facility must examine the patient within 4 h of arrival and may authorize detention for up to 3 days. The doctor must inform the Community Advocate and Mental Health Tribunal of the patient’s admission within 12 h and the patient must receive a physical and psychiatric examination within 24 h of detention.

New South Wales

The Mental Health Act in New South Wales allows for a patient requiring involuntary admission to be detained in a declared mental health facility (which includes EDs) on the certificate of a doctor (or trained ‘accredited person’) who has personally examined the patient immediately or shortly before completing the certificate.

For a mentally ill patient, the certificate is valid for 5 days from the time of writing, whereas for a mentally disordered patient, the certificate is valid for 1 day. Mentally disordered patients cannot be detained on the grounds of being mentally disordered on more than three occasions in any 1 month.

Part of the certificate, if completed, directs the police to apprehend and bring the patient to hospital and also enables them to enter premises without a warrant.

An involuntary patient must be examined by an authorized medical officer (including emergency doctors) as soon as practicable, but within 12 h of admission. The patient cannot be detained unless further certified mentally ill or disordered. This doctor cannot be the same doctor who requested admission or certified the patient. After their own examination, the medical officer must arrange for a second examination as soon as practicable, this time by a psychiatrist. If neither doctor thinks that the person is mentally ill or disordered, then the person must be released from the hospital.

A patient who has been certified as mentally disordered, but not subsequently found to be mentally ill, cannot be detained for more than 3 days and must be examined by an authorized medical officer at least once every 24 h and discharged if no longer mentally ill or disordered or if appropriate and less restrictive care is available. New South Wales legislation involves several checks and balances, including timely and regular Mental Health Review Tribunal assessment for all patients recommended for involuntary care.

New Zealand

In New Zealand, a person aged 18 years or over may request an assessment by the area mental health service if it has seen the person within the last 3 days and believes the person to be suffering from a mental disorder. The request may be accompanied by a certificate from a doctor who has examined the ‘proposed patient’ within the preceding 3 days and who believes that the person requires compulsory assessment and treatment. The medical certificate must state the reasons for the opinion and that the patient is not a relative. The area mental health service must then arrange an assessment examination by a psychiatrist or other suitable person forthwith. If the assessing doctor considers that the patient requires compulsory treatment, the patient may be detained in the ‘first period’ for up to 5 days. Subsequent assessment may result in detention for a ‘second period’ of up to 14 more days, after which a ‘compulsory treatment order’ must be issued by a family court judge.

Northern Territory

Any person with a genuine interest in or concern for the welfare of another person may request an assessment by any medical practitioner to determine if that person is in need of treatment under the Northern Territory Mental Health Act. The assessment must then occur as soon as practicable and a subsequent recommendation for psychiatric examination made if the doctor believes that the person fulfils the criteria for involuntary admission on the grounds of mental illness or mental disturbance. The person may then be detained by police, ambulance officers or the doctor making the recommendation and taken to an approved treatment facility, where the person may be held for up to 12 h. The Northern Territory Act acknowledges that delays in this process are likely and enshrines a process to account for this, including the use of interactive video conferencing. A psychiatrist must examine and assess the recommended person at the approved treatment facility and must either admit as an involuntary patient or release the patient if the criteria for involuntary admission are not fulfilled.

A patient admitted on the grounds of mental illness may be detained for 24 h or 7 days if the recommending doctor was also a psychiatrist. Patients admitted on the grounds of mental disturbance may be detained for 72 h or have that extended by 7 days if two examining psychiatrists believe that the person still requires involuntary treatment and cannot or will not consent. Frequent psychiatric reassessment of detained and admitted patients is required to either extend admission or release patients who do not fulfil involuntary criteria.

Queensland

In Queensland, the recommendation for involuntary assessment of a patient must be made by a doctor who has personally examined the patient within the preceding 3 days and is valid for 7 days from the time the recommendation was made. The recommendation needs to be accompanied by an ‘application’ for assessment made by a person over the age of 18 years who has seen the patient within 3 days. The person making the application cannot be the doctor making the recommendation or be a relative or employee of the doctor. The recommendation enables the health practitioner, ambulance officer or police, if necessary, to take the patient to a mental health service or public hospital for assessment. Once there, or if the recommendation was made at a hospital, the assessment period lasts for no longer than 24 h.

The patient must be assessed by a psychiatrist (who cannot be the recommending doctor) as soon as practicable and, if the treatment criteria apply, will have the involuntary status upheld through an involuntary treatment order. The assessment period can be extended up to 72 h by the psychiatrist after regular review.

South Australia

In South Australia, a doctor or trained authorized health professional (who may be a nurse, allied or aboriginal health worker) who considers that a patient requires involuntary admission authorizes a Level 1 Detention and Treatment Order, which is valid for 7 days. A psychiatrist or authorized medical practitioner (senior psychiatry registrar) must examine the person within 24 h or as soon as practicable.

In recognition of the difficulties in accessing appropriate care for people in remote and rural environments, the South Australian Mental Health Act allows for audiovisual conferencing and a range of community and inpatient based treatment orders. A wider range of health professionals can authorize treatment orders so that early access to care in the least restrictive environment can occur.

Tasmania

In Tasmania, an application for involuntary admission of a person may be made by a close relative or guardians or an ‘authorized officer.’ A medical practitioner must then assess the person and, if satisfied that the criteria are met, make an order for admission and detention as an involuntary patient in an approved hospital. This initial ‘assessment order’ is valid for 72 h and gives authority for the patient to be taken to the hospital and detained, whereupon a psychiatric assessment must be carried out within 24 h and the assessment order extended for up to 72 h or discharged. A ‘treatment order’ for the continuing detention of a person as an involuntary patient can only be made by application (including an individualized treatment plan) through an independent tribunal.

Victoria

A person may be admitted to and detained in an approved mental health service once the ‘request’ and the ‘recommendation’ have been completed. The request can be completed by any person over 18 years of age, including relatives of the patient, but cannot be completed by the recommending doctor. The recommendation is valid for 3 days after completion and the recommending doctor must have personally examined or observed the patient.

The request and recommendation are sufficient authority for the medical practitioner, police officer or ambulance officer to take the person to a mental health service or to enter premises without a warrant and to use reasonable force or restraint in order to take the person to a mental health service. Prescribed medical practitioners (psychiatrists, forensic physicians, doctors employed by a mental health service, the head of an ED of a general hospital or the regular treating doctor in a remote area) are also enabled to use sedation or restraint to enable a person to be taken safely to a mental health service.

Once admitted, the patient must be seen by a medical practitioner employed by the mental health service as soon as possible, but must be seen by a registered psychiatrist within 24 h of admission. The admitting doctor must make an involuntary treatment order, which allows for the detention of the patient until psychiatrist review and the urgent administration of medication if needed. The psychiatrist can then either authorize further detention, a community treatment order or discharge the patient.

Western Australia

In Western Australia, a person who requires involuntary admission is referred, in writing, for examination by a psychiatrist in an authorized hospital. The referring doctor or authorized mental health practitioner must have personally examined the person within the previous 48 h and may also make a detention and/or transport order which allows safe transport involving the police or ambulance personnel if required. These orders are valid for up to 72 h, although there are provisions for time extensions outside the metropolitan area.

The referral for assessment is valid for 72 h (although this can also be extended); however, the patient must be examined by a psychiatrist within 24 h of admission and cannot be detained further if not examined. The patient can be detained for further assessment for up to 72 h after initial admission on the order of the psychiatrist, after which time the patient is formally admitted as an involuntary patient, discharged on a community treatment order or released.

Persons unable to recommend a patient for involuntary admission

New Zealand and most states, except for the ACT, specify that certain relationships prevent a doctor from requesting or recommending a patient for involuntary admission.

The recommending doctor cannot be a relative (by blood or marriage) or guardian of the patient and, in addition, in the Northern Territory, Queensland, Tasmania and Western Australia, the doctor cannot be a business partner or assistant of the patient. In Queensland and Tasmania, the recommending doctor cannot be in receipt of payments for the maintenance of the patient.

In New South Wales, the doctor must declare, on the schedule, any direct or indirect pecuniary interest, or those of their relatives, partners or assistants, in a private mental health facility. In Western Australia, the doctor cannot hold a licence from or have a family or financial relationship with the licence holder of a private hospital in which the patient will be treated, nor can the doctor be a board member of a public hospital treating the patient.

Use of sedation or physical restraint

From time to time a patient may need to be sedated or even restrained. The various mental health acts vary considerably in dealing with this issue and accepted clinical practice has evolved differently in each jurisdiction and does not necessarily reflect subtleties within the legislation.

Generally, patients committed involuntarily are subject to treatment necessary for their care and control and this may reasonably include the administration of sedative or antipsychotic medication as emergency treatment. In general, sedation or restraint must be the minimum that is necessary to prevent the patient from self-harming or harming others and careful documentation of the reasons for restraint and the types of restraint is required. While restrained, access to clothing, sustenance, toilet facilities and other basic comforts must be assured.

Patients who are physically or pharmacologically restrained must be closely supervised and not left alone or in the care of persons not trained or equipped to deal with the potential complications of these procedures. Transporting these patients to a mental health service should be done by suitably trained medical or ambulance staff and not delegated to police officers or other persons acting alone.

The ACT specifies that sedation may be used to prevent harm, whereas Western Australia specifies that sedation can be used for emergency treatment without consent and that the details must be recorded in a report to the Mental Health Review Board. Queensland allows a doctor to administer medication for recommended patients without consent to ensure safety during transport to a health facility.

Victoria specifically permits the administration of sedative medication by a ‘prescribed medical practitioner’ to allow for the safe transport of a patient to a mental health service. There is a schedule to complete if this is undertaken. The South Australian law stipulates that medication can only be used for therapeutic purposes and that chemical, physical restraint and seclusion is to be used as a last resort for safety reasons and not as a punishment or for the convenience of others.

The legislation is more specific with regard to the use of physical restraint or seclusion. In the ACT, this can be done to prevent an immediate and substantial risk of harm to the patient or others or to keep the patient in custody.

Queensland requires that restraint used for the protection of the patient or others can only be done on an ‘order’ but is permissible for the purposes of treatment if it is clinically appropriate. Victoria permits the restraint of involuntary patients for the purposes of medical treatment and the prevention of injury or persistent property destruction. Victoria also allows the use of restraint by ambulance officers, police or doctors in order to safely transport the patient to a mental health service, but this must be documented in the recommendation schedule. Tasmania differentiates between chemical restraint and chemical treatment and allows for both chemical and physical restraint as emergency short-term interventions to prevent harm, damage or interference, break up an affray or facilitate transport. The Chief Civil Psychiatrist is required to develop standing orders for clinical use regarding these issues.

Both the Northern Territory and Western Australia permit the use of restraint for the purposes of medical treatment and for the protection of the patient, other persons or property. In Western Australia, this authorization must be in writing and must be notified to the senior psychiatrist as soon as possible, while in the Northern Territory, it must be approved by a psychiatrist or the senior nurse on duty in the case of an emergency.

The New Zealand Mental Health Act makes minimal specific reference to restraint or sedation but enables any urgent treatment to protect the patient or others and allows hospitals and police to take all reasonable steps to detain patients for assessment and treatment. Authority is given to administer sedative drugs if necessary, but the Act mandates a record of this for the area mental health service.

New South Wales has a Reference Guide specifically for mental health issues in the ED which covers sedation and restraint issues. The law permits the use of involuntary sedation for acute behavioural disturbance in an emergency situation in order to prevent individual death or serious danger to the health of others under the common law principle of ‘Duty of Care’. The same applies for children, although consent should be sought from both children or adolescents and their parents or guardians. For the use of physical restraints, although acknowledged as a clinical decision, four pre-conditions must be met:

Emergency treatment and surgery

On occasions, involuntary patients may require emergency medical or surgical treatment. New Zealand and most states, except for Queensland, make provision for this in their legislation, in that patients can undergo emergency treatment without consent, but usually only with the approval of the relevant mental health authorities or treating psychiatrist. In New Zealand, treatment that is immediately necessary to save life, prevent serious damage to health or prevent injury to the person or others can be undertaken without consent.

Victoria has the most specific reference to this treatment by making special allowance for a patient requiring treatment that is life sustaining or preventing serious physical deterioration to be admitted as an involuntary patient to a general hospital or ED for the purposes of receiving treatment. The patient is deemed to be on leave from the mental health service and all the other provisions of the Act apply.

Apprehension of absent involuntary patients

Involuntary patients who escape from custody or who fail to return from ‘leave’ are considered in most state mental health acts to be ‘absent without leave’ (AWOL) or ‘unlawfully at large’. Authorized persons, including ambulance officers, mental health workers and police, have the same powers of entry and apprehension as for other persons to whom a recommendation or certificate relates.

In New Zealand, any compulsory patient who becomes AWOL may be ‘retaken’ by any person and taken to any hospital within 3 months of becoming absent. If not returned after 3 months the patient is deemed to be released from compulsory status.

Powers of the police

The police in all states and New Zealand have powers in relation to mentally ill persons who may or may not have been assessed by a doctor. For someone who is not already an involuntary patient and who is reasonably believed to be mentally ill, a risk to self or others and requiring care, police are able to enter premises and apprehend, without a warrant, and to use reasonable force if necessary, in order to remove the person to a ‘place of safety’. Generally, this means taking the person to a medical practitioner or a mental health service for examination without undue delay.

South Australia and Queensland specifically include ambulance or other authorized officers within this legislation and acknowledge that they often work together with police to detain and transport people for mental health assessment. In Tasmania, people may only be held in protective custody for the purposes of medical assessment for no longer than 4 h and then released if no involuntary assessment order has been made. The ACT law is moving towards replacing police with ambulance paramedics in the role of emergency apprehension and transport to hospital for assessment.

Some states (ACT, New South Wales and Victoria) make special mention of a threatened or actual suicide attempt as justification for police apprehension and transfer to a health facility. New South Wales allows police discretion after a person who appears mentally disordered has committed an offence (including attempted murder), to determine whether it is beneficial to their welfare to be detained under the mental health act rather than under other criminal law. The Victorian and South Australian Acts, in contrast, acknowledge that police do not need clinical judgement about mental illness but may exercise their powers based on their own perception of a person’s appearance and behaviour that may be suggestive of mental illness.

In New Zealand, detention by police is limited to 6 h, by which time a medical examination should have taken place. Ideally, police should not enter premises without a warrant, if it is reasonably practicable to obtain one.

The same powers apply to involuntary patients who abscond or are absent without leave, although some states have specific schedules or orders to complete for this to be done. In general, once police become aware of the patient they are obliged to make attempts to find and return them to what can be viewed as lawful custody.

Prisoners with mental illness

Mental illness among people in prison is extremely prevalent, either as a cause or as a result of incarceration. New Zealand and most Australian states and territories include provisions for prisoners with mental illness within their mental health legislation. While the healthcare of prisoners is generally managed within regional forensic systems, EDs in rural and less-well-resourced areas can become a site of care for prisoners with acute psychiatric illness.

The New Zealand Act states that prisoners with mental illness who require acute care can be transferred to a general hospital for involuntary psychiatric treatment if the prison is unable to provide that care. Australian Acts in New South Wales, the Northern Territory and Victoria all include similar specific provisions for mentally ill prisoners to be able to access involuntary care in public hospitals if needed. New South Wales has separate legislation specifically dealing with mental illness in the forensic setting (NSW Mental Health [Forensic Provisions] Act 1990), while the Tasmanian Act includes a large section involving the admission, custody, treatment and management of forensic patients within secure mental health units. The Victorian Act has some detail in this matter although, in practice, rarely relies on public hospitals due to the development of a stand alone forensic psychiatric hospital. Both Queensland and Western Australia enshrine the same principle of allowing prisoners access to general psychiatric treatment, although their legislation is less specific, while the South Australian Act does not mention prisoners at all. The ACT will incorporate care for prisoners with mental illness in their new Act, emphasizing concern for the community who may be affected by prisoners with mental illness, improving communication between forensic and health services and allowing prisoners with mental illness access to appropriate healthcare. In all jurisdictions, there is significant overlap with other laws such as Crimes and Prisons Acts, which also mention health needs of prisoners.

Offences in relation to certificates

Most states and New Zealand specify in their respective mental health acts that it is an offence to make wilfully a false or misleading statement in regard to the certification of an involuntary patient.

Some states (New South Wales, South Australia, the Northern Territory and Victoria), except in certain circumstances, also regard failure personally to examine or observe the patient as an offence.

Protection from suit or liability

New Zealand and all Australian states specify in their Mental Health Acts that legal proceedings cannot be brought against doctors acting in good faith and with reasonable care within the provisions of the Mental Health Act relevant to their practice.

Information and patient transfer between jurisdictions

All Australian states and territories include special provisions for the apprehension, treatment and transfer of mentally ill patients from other jurisdictions. State governments can enter into agreements to recognize warrants or orders made under ‘corresponding law’ in other states or territories, as long as appropriate conditions are met within their own law. Thus, a patient under an involuntary detention or community treatment order in another state can be apprehended and treated under the corresponding law in a different jurisdiction. Authority is given to police and doctors to detain such patients and information to facilitate assessment and treatment can be shared between states.

Deaths

Involuntary patients should be considered to be held in lawful custody, whether in an ED, as an inpatient in a general hospital or psychiatric hospital or as an AWOL. As such, the death of such a patient must be referred for a coroner’s investigation.

25.2 The coroner: the Australasian and UK perspectives

Robyn Parker and Jane Terris

Australasia

Introduction

The function of the coroner is to investigate and report the circumstances surrounding a person’s death. A coronial inquest is a public inquiry into one or more deaths conducted by a coroner within a court of law. Legislation in each Australian state and territory defines the powers of this office and the obligations of medical practitioners and the public towards it. The process effectively puts details concerning a death on the public record and is being increasingly used to provide information and recommendations for future injury prevention.

As many people die each year either in an emergency department (ED) or having attended an ED during their last illness, it is almost inevitable that emergency physicians will become involved in the coronial process at some stage during their career. Such involvement may be brief, such as the discharge of a legal obligation by reporting a death, or may extend further to providing statements to the coroner regarding deaths of which they have some direct knowledge. Later, the coroner may require them to appear at an inquest to give evidence regarding the facts of the case and, possibly, their opinion. Occasionally, the coroner requires a suitably experienced emergency physician to provide an expert opinion regarding aspects of a patient’s emergency care.

Although the inquisitorial nature of the coronial process is sometimes threatening to medical practitioners, their involvement is a valuable community service. In addition, they may obtain important information regarding aspects of a patient’s clinical diagnoses and emergency care which may improve the provision of emergency care to future patients.

Legislation

The office of the coroner and its functions, procedures and powers is created by state and territory legislation. The legislation also creates obligations on medical practitioners to notify the coroner of reportable deaths and to cooperate with the coroner by providing certain information in the course of an inquiry. The normal constraints of obtaining consent for the provision of clinical information to a third party do not apply in these circumstances.

The coroner is vested with wide-ranging powers to assist in obtaining information. In practice, the police are most commonly used to conduct the investigation. Under the various Coroners Acts they have the power to enter and inspect buildings or places, take possession of and copy documents or other articles, take statements and subpoena people to appear in court. The coroner has control of a body whose death has been reported and may direct that an autopsy be performed.

As each Australian state and territory legislation is different, emergency physicians must be familiar with the details in their particular jurisdiction. The current legislation in each state and territory is the following:

Reportable deaths

Most deaths that occur in the community are not reported to a coroner and, consequently, are not investigated. The coroner has no power to initiate an investigation unless a death is reported, but may choose to investigate the death at the request of a next of kin or a person who registers themselves as an interested party. If a medical practitioner is able to issue a medical certificate of the cause of death, the Registrars-General of that state or territory may issue a death certificate and the body of the deceased may be lawfully disposed of without coronial involvement.

In general, to issue a certificate of the cause of death, a doctor must have attended the deceased during the last illness and the death must not be encompassed by that jurisdiction’s definition of a reportable death. It is essential that every medical practitioner has a precise knowledge of what constitutes a reportable death within the jurisdiction.

It is uncommon for a doctor who is working in an ED to have had prior contact with a patient during the last illness. Therefore, even if sure of the reason why the patient died, the doctor is often unable to complete a medical certificate of the cause of death. It is quite permissible, and even desirable, under these circumstances, to contact the patient’s treating doctor to inquire as to whether that doctor is able to complete the certificate. This process reduces the number of deaths that must be reported and assists families who may be distressed about coronial involvement.

All Australian Coroners Acts contain a definition of the deaths that must be reported. Although the precise terminology varies, there are many similarities between them. In general, each Act has provisions for inquiring into deaths that are of unknown cause or that appear to have been caused by violent, unnatural or accidental means. Many acts also refer to deaths that occur in suspicious circumstances and some specifically mention killing, drowning, dependence on non-therapeutic drugs and deaths occurring while under anaesthesia. The Tasmanian Act goes further to specify deaths that occur under sedation.

As an example, the Victorian Coroners Act 2008 defines a reportable death as a death that is unexpected, unnatural or violent or resulting from an accident or injury. The definition has also been widened to include a death during or after a medical procedure where a doctor would not reasonably have expected the person to die. ‘Medical procedure’ is defined broadly to include ‘imaging, internal examination and surgical procedure’. A reportable death under the Act of 2008 is also the death of a person placed in custody, including deaths involving police or prison officers attempting to take a person into custody.

Despite the seemingly straightforward definitions given in the various acts, there are many instances where it may not be clear whether a death is reportable or not. Emergency physicians are often faced with situations where there is a paucity of information regarding the circumstances of an event and where the cause of death may be difficult to deduce. Correlation between the clinical diagnoses recorded on death certificates and subsequent autopsies has been consistently shown to be poor. What exactly constitutes unexpected, unnatural or unknown is open to debate and may require some judgement. In all cases, the coroner expects the doctor to act with common sense and integrity. If at all in doubt it is wise to discuss the circumstances with the coroner or assistant and to seek advice. This conversation and the advice given must be recorded in the medical notes.

The process of reporting a death is generally a matter of speaking to the coroner’s assistants (often referred to as coroner’s clerks), who will record pertinent details and, if necessary, investigate. The report should be made as soon as practicable after the death. A medical practitioner who does not report a reportable death is liable to a penalty.

Even though coroners’ offices and the police work closely together, reporting a death to the coroner is not necessarily equivalent to reporting an event to the police. If it is possible that a person has died or been seriously injured in suspicious circumstances, then it is prudent to ensure that the police are also notified.

A coronial investigation

After a death has been reported, the coroner or designated assistant may initiate an investigation. This is most commonly conducted by the police assisting the coroner, with an autopsy conducted by a forensic pathologist.

The body, once certified dead, becomes part of that investigation and should be left as far as possible in the condition at death. If the body is to be viewed by relatives immediately, it is often necessary to make it presentable. This must be done carefully, so as to not remove or change anything that may be of importance to the coroner. If a resuscitation was attempted all cannulae, endotracheal tubes and catheters should be left in situ. All clothing and objects that were on (or in) the deceased should be collected, bagged and labelled. All medical and nursing notes, radiographs, electrocardiographs and blood tests should accompany the body if it is to be transported to a place as directed by the coroner.

Medical notes taken during or soon after the activity of a busy resuscitation are often incomplete. It is not easy to recall accurately procedures, times and events when the main task is to prevent someone from dying. Similarly, after death there are many urgent tasks, such as talking to relatives, notifying treating or referring doctors and debriefing staff. It is essential, however, that the documentation is completed as accurately and thoroughly as possible. The notes must contain a date and time and clearly specify the identity of the author. If points are recalled after completing the notes, these may be added at the end of the previous notes, again with a time and a date added. Do not under any circumstances change or add to the body of the previous notes.

In addition to completing the medical notes, a medical practitioner may be requested to provide a statement to the coroner regarding the doctor’s involvement with the deceased and an opinion on certain matters. Such a statement should be carefully prepared from the original notes and written in a structured fashion, using non-medical terminology where possible. The statement often gives the opportunity for the medical practitioner to give further information to the coroner regarding medical qualifications and experience, the position fulfilled in the department at the time of the death and a more detailed interpretation of the events. If a statement is requested from junior ED staff, it is strongly advisable for these to be read by someone both clinically and medicolegally experienced.

Providing honest, accurate and expeditious information to relatives when a death occurs assists in preventing misunderstandings and serious issues arising in the course of a coronial investigation. Relatives vary enormously in the quantity and depth of medical information they request or can assimilate after an unexpected death. It is wise not only to talk to the relatives present at the death but also to offer to meet later with selected family members. Clarification with the family of what actually occurred, what diagnoses were entertained and what investigations and procedures were performed is not only good medical practice but can allay concerns regarding management. Such communication, as well as aiding in the grieving process for relatives of the deceased, may avert an unnecessary coronial investigation initiated by relatives seeking answers about the death by contacting the coroner.

If a significant diagnosis was missed or inappropriate or an inadequate treatment given, or a serious complication of an investigation or procedure occurred, assistance and advice from the hospital insurers and medical defence organizations should be sought before talking to the family. However difficult it may be, it is far better that the family is aware of any adverse occurrences before the inquest than for them to harbour suspicions or to get a feeling something is being covered up. Such a conversation should be part of an open disclosure approach to patient care, involving open communication with a patient or family following an adverse or unexpected event. The coroner is far more likely to be sympathetic to a genuine mistake or omission when it has been discussed with the family and the hospital has taken steps to prevent a recurrence.

Expert opinion

Having gathered all the available information regarding a death, the coroner may decide that expert opinion is necessary on one or more points. Commonly, this involves the standard of care afforded to the deceased. It may, however, also include issues such as the seniority of doctors involved, the use of appropriate investigations, the interpretation of investigations and the occurrence of complications of a procedure. The coroner relies heavily on such opinions for the findings and the selection of an appropriate expert is essential.

The person selected by the coroner to give this opinion should possess postgraduate specialist medical qualifications and be broadly experienced in the relevant medical specialty. For events occurring in the ED, a senior emergency physician with over 5 years of experience is usually most appropriate. The specialist medical colleges may be requested to nominate such a person.

The emergency physician requested to give expert opinion must be able to review all of the available relevant information. Such persons must also consider themselves adequately qualified and experienced to provide an opinion and to answer any specific questions the coroner may have requested to be addressed. The doctor must have the time and ability to provide a comprehensive statement and to appear as a witness at the inquest if requested and to act impartially. The doctor should decline involvement if an interest in the outcome of the case could be implied or if there is a close relationship between the expert witness and any doctors or other personnel who are being investigated as part of the coronial process. Because of the close-knit nature of the medical community, an expert witness is often sought from a location remote from where the death occurred, such as interstate.

A coronial inquest

A coronial inquest is a public inquiry into one or more deaths. Deaths may be grouped together if they occurred in the same instance or in apparently similar circumstances. The purpose of the inquest is to put findings on the public record. These may include the identity of the deceased, the circumstances surrounding the death, the medical cause of death and the identity of any person who contributed to the death. The coroner may also make comments and recommendations concerning matters of health and safety. In some jurisdictions these are termed ‘riders’. In addition, as His Honour BR Thorley pointed out, the inquest serves to:

…include the satisfaction of legitimate concerns of relatives, the concern of the public in the proper administration of institutions and matters of public and private interest…

The inquest does not serve to commit people for trial or to provide information for a subsequent criminal investigation.

With broad terms of reference and the ability to admit testimony that may not be allowed in criminal courts, inquests interest many people, not only those who may have been directly involved. They are often highly publicized media events and may provoke political comment, especially where government bodies are involved. A medical practitioner served a subpoena to attend should prepare carefully, both individually and in conjunction with the hospital, and should ensure that he or she has legal representation, either individually or through the hospital insurers. Where the doctor subpoenaed is being provided legal counsel by the hospital, it is vital to ensure that the hospital administrators support the actions of the doctor in relation to the death. It is advised that, in the event of being subpoenaed to a coronial inquest, the doctor seek advice immediately from the appropriate medical defence agency.

Preparation for an inquest begins at the time of the death. Complete and accurate medical notes, together with a carefully considered statement, provide a solid foundation for giving evidence and handling any subsequent issues. Statements containing complex medical terminology, ambiguities or omissions only serve to create confusion. Discuss the case with colleagues who are not directly involved and have the hospital lawyers read the statement before it is submitted.

Appearing at an inquest can be a stressful event, especially if, on a review of the circumstances, a doctor’s actions or judgement may be called into question. Professional peer support, as well as legal advice, should be offered to all medical staff. Simple actions, such as a briefing on court procedures and some advice on how to deal with cross-examination, can be of immense value.

A coroner’s court is conducted with a mix of ‘inquisitorial’ and ‘adversarial’ legal styles. It is inquisitorial in that the coroner may take part in direct proceedings and can question witnesses and appoint court advisers. It is adversarial in that parties with a legitimate interest can be represented in proceedings and can challenge and test witnesses’ evidence, especially where it differs from what they would like presented. Interested parties generally attend court and can ask any questions of the doctor through their own legal representative or through the police counsel to the coroner. The ‘rules of evidence’ are more relaxed in the coroner’s court than in a criminal court. Hearsay evidence – that is, evidence of what someone else said to a witness – is generally admissible. Despite these differences, it is important to remember that it is no less a court than a criminal court and demands the same degree of respect and professional conduct one would accord to the latter.

Coronial findings

At the conclusion of an inquest, the coroner makes a number of findings directed at satisfying the aims of that inquest. These findings are made public and are often of interest to those who are directly involved, as well as to a wider audience.

The findings of an inquest in which the conduct of a particular emergency physician, ED or hospital has been scrutinized will be of particular interest. Although it is always pleasing to have either positive or a lack of negative comment delivered in the finding, criticism of some aspect of the conduct of an individual, department, hospital or the medical system in general is not uncommon. Unfortunately, it is often this criticism that attracts the most public attention and, somewhat unfairly, the public perception of our acute healthcare system is shaped by the media’s attention to coronial findings.

In the recent past, coroners have commented on inadequate training, experience and supervision of junior doctors, inadequate systems of organization within departments and poor communication between doctors and family members.

Although adverse or critical findings have no legal weight or penalties attached to them, they are in many respects a considered community response to a situation in which the wider population has a vested interest. Used constructively, they can be extremely useful in convincing hospital management that a problem exists and beginning a process for effecting positive change within a department or institution.

The UK

Introduction

The investigation into the circumstances surrounding a death is an important part of a civilized society. Accurate recording of the cause of death serves many purposes, including accurate disease surveillance, the detection of secret homicide and the detection of potentially avoidable factors that have contributed to a death. Various death investigation systems exist around the world. The UK uses the coronial system, Scotland the procurator fiscal. By virtue of the patient population encountered by emergency physicians and the types of deaths that are subject to investigation, emergency physicians may expect to find themselves in contact with either the coroner or the procurator fiscal system during their working lives, thus necessitating an understanding of the workings of these systems.

History of the coroner

The history of the coroner’s office is an interesting reflection of events that shaped our civilization and is in constant evolution. The Shipman Inquiry (2003) and the Fundamental review of Death Certification and Investigation (2003) identified problems within the services available to bereaved families and the process of death certification and led to a reform of the system in the UK in the form of the Coroners and Justice Act 2009.

The office of the coroner was established in 1194 and its primary function then was that of protection of the crown’s pecuniary interests in criminal proceedings. The coroner was involved when a death was sudden or unexpected or a body was found in the open; however, aside from the duty to ensure the arrest of anyone involved in homicide, the coroner held a significant role in the collection of the deceased’s chattels and collection of various fines [1].

Introduction of the Births and Deaths Registration Act in 1836, mandated registration of all deaths before burial could legally occur. This may have arisen out of concern regarding accurate statistical information concerning deaths, but also concern about hidden homicide. Another act introduced the same year enabled coroners to order a medical practitioner to attend an inquest and perform an autopsy in equivocal cases. The Coroners Act of 1887 saw a shift of emphasis from protection of financial interests to the emphasis that remains today, namely the medical cause of death and its surrounding circumstances with eventual community benefit in mind.

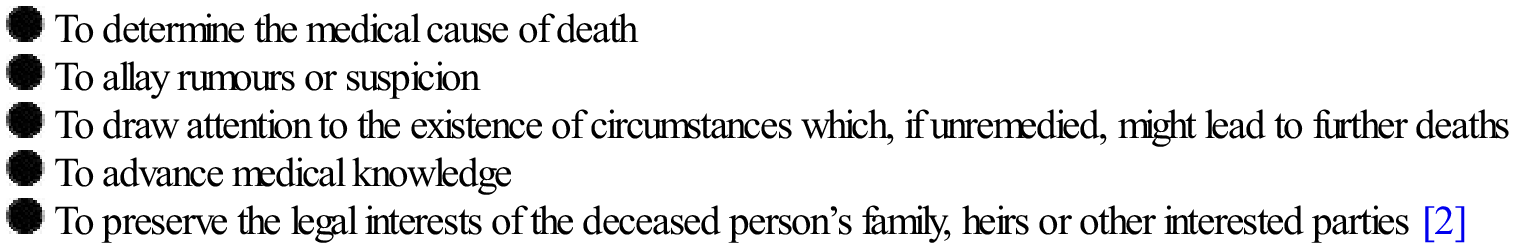

The Broderick committee was appointed in 1965 to review death certification in response to adverse publicity about inquests and pressures to improve death certification. Their report published in 1971 contained 114 recommendations, many of which were enacted. Table 25.2.1 lists the reasons the Broderick Committee considered the purpose of an inquest [2].

Table 25.2.1

Reasons for an inquest (according to the Broderick committee)

The Coroners Act (1988) states that a coroner shall hold an inquest into a death when there is:

…reasonable cause to suspect that the deceased has died a violent or unnatural death, has died a sudden death of which the cause is unknown, or has died in prison or in such a place or circumstances as to require an inquest under any Act [3].

The Coroners and Justice Act 2009 introduced changes to the structure and appointment system for coroners, more flexibility between working areas of coroners and the mandate for all coroners to have held a legal qualification for 5 years, which was intended to standardize practice and ensure sufficient legal understanding for coroners. The new appointment of a chief coroner, with a senior legal background, and with annual reporting to the government, was recommended to be responsible for establishing national training and governance standards and developing a charter for improving services to bereaved families. The death certification system under the Act was modified to provide consistency whether the body is buried or cremated and to ensure that adequate scrutiny of the circumstances around the death happens and is documented. The introduction of a medical examiner attached to a primary care trust to scrutinize all death certificates prior to burial or cremation replaced the previously medically unqualified registrar.

Structure of the coroner system in the UK

Coroners are independent judicial officers who have a legal background, including having been a qualified barrister or solicitor for at least 5 years and, in addition, some may also have a medical background. They are responsible to the Chief Coroner, a senior legal practitioner who must have previously held the position of high court or circuit judge and, ultimately, is responsible to the Crown through the Lord Chancellor. They must work within the laws and regulations that apply to them: The Coroners and Justice Act 2009 replaced the previous framework as described in The Coroners Act 1988, Coroners Rules 1984 and the Model Coroners Charter. There are approximately 148 coroner’s districts throughout England and Wales and each district has a coroner and a deputy and possibly several assistant deputy coroners. Coroners are assisted in their duties by coroner’s officers, who are frequently police officers or ex-police officers and whose work is dedicated solely to coronial matters. This follows long-established practice and has probably arisen because of the significant proportion of cases in which police are the notifying agent. The nature of a coronial investigation requires a person to possess knowledge about legal matters and skill in information gathering. From a practical viewpoint, the coroner’s assistants may be responsible for performing such duties as attending the scene of a death, arranging transport of the body to the mortuary, notification of the next of kin and obtaining statements from relevant parties. Clearly, variation in the structure of the service between regions is inevitable and reflects the size, composition and workload within the district [4].

The 2009 reforms to the coronial process

The UK coronial system underwent fundamental changes following the Coroners and Justice Act 2009, which constituted the first major reforms of the existing system for over 100 years. It included changes to the investigation process for certain deaths previously governed by the Coroners Act 1988.There were also reforms of the certification and registration of deaths. The need for reform was galvanized by several landmark cases including the Shipman Inquiry (2003), in which the system had not identified and isolated a pattern of criminal activities spanning years by the UK GP Dr Harold Shipman, and the Fundamental Review of death Certification and Investigation (2003) which revealed a number of problems and inconsistencies in the process of death certification and the services available to bereaved relatives. Other findings prompting reforms included a lack of leadership and training for coroners and a perceived deficiency of medical knowledge within the system. The structure, training and appointment systems for coroners were changed to include a Chief Coroner, improved training and guidance for coroners, who have to be legally qualified, and powers allowing evidence to be obtained, with search and entry where necessary. Changes to the process for issuing a death certificate include the replacement of a non-medically qualified registrar with a Medical Examiner, reporting to a Chief Medical examiner, who scrutinizes and, if necessary, recommends investigation, following the issuing of the death certificate.

Outline of the coronial system

Upon notification of a death, the coroner makes initial inquiries and may direct a pathologist, who is generally a specialist forensic pathologist, to perform a post-mortem autopsy. Sometimes it becomes clear at this early point that the death is a natural one and does not fall within the Coroners Act, thus no further investigation is required and a death certificate is issued. In other circumstances, further investigations occur and relevant information is gathered. If the coroner is subsequently satisfied that the death is natural, again no inquest is required. In other cases, or in certain prescribed circumstances, an inquest is held. At the conclusion of an inquest, a finding or verdict is delivered. This verdict must not be framed in a way that implies civil or criminal liability.

Reportable deaths

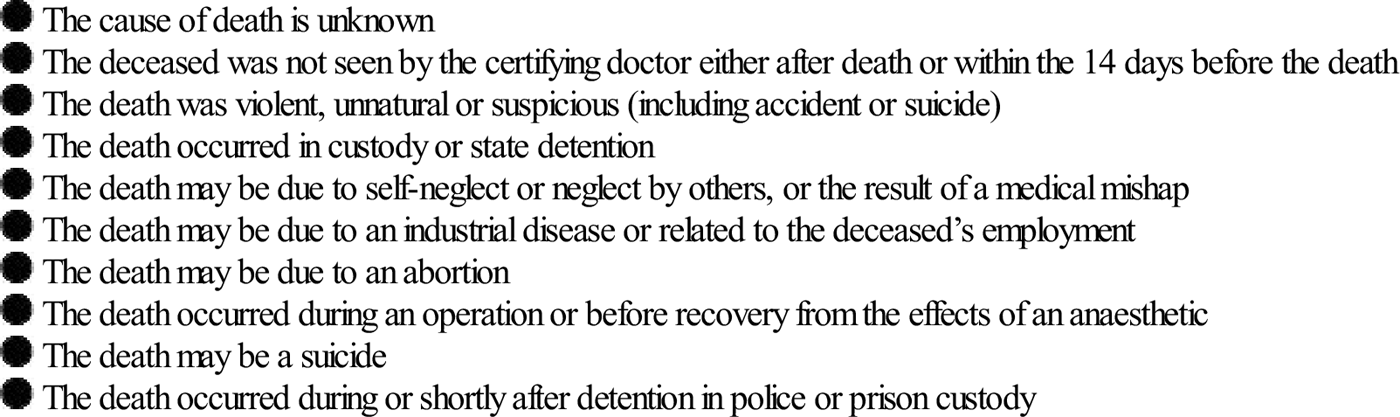

As opposed to the Australasian situation, there is no statutory obligation in the UK for a doctor or any member of the public to report certain deaths to the coroner, however, an ethical responsibility exists and it is recognized practice to do so in particular circumstances. A 1996 letter from the Deputy Chief Medical Statistician to all doctors outlined these circumstances (Table 25.2.2) [5].

Table 25.2.2

Circumstances in which a death should be reported to the coroner

Each booklet of medical death certificates also contains a reminder of the deaths that a coroner needs to consider. The list is not exhaustive.

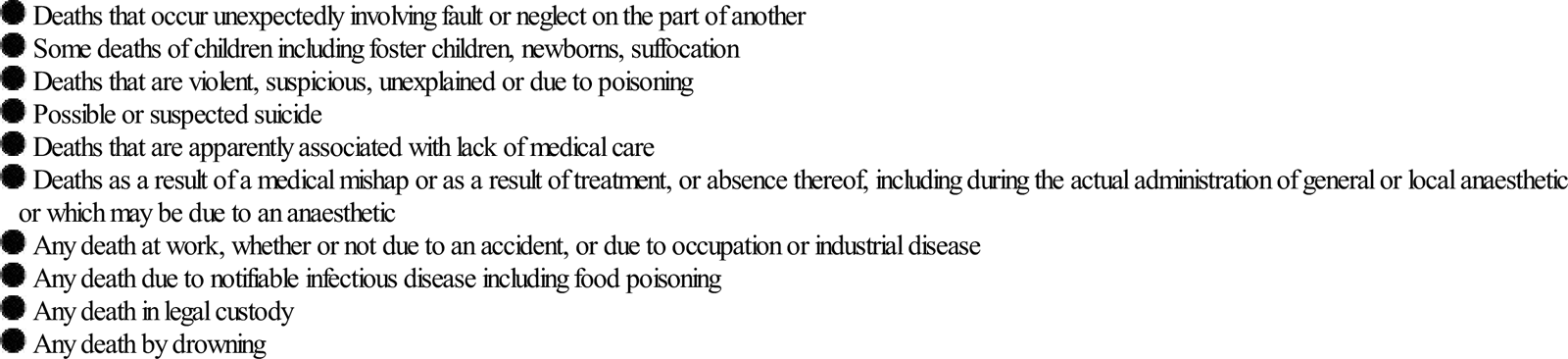

Scotland

In Scotland, the role of death investigation is undertaken by the procurator fiscal’s office, which is also responsible for the investigation and prosecution of crime and also has responsibility for any treasure found within the district! The registrar of births and deaths in Scotland has a statutory duty to report certain deaths, for example, those due to industrial disease and those occurring during surgery, to the procurator fiscal. The spectrum of deaths investigated is essentially the same as in England and Wales; however, more specific guidelines regarding deaths possibly related to medical mismanagement are provided (Table 25.2.3).

Table 25.2.3

Circumstances in which a death should be reported to the procurator fiscal in Scotland