Section 24 Academic Emergency Medicine

24.1 Research methodology

Initiating the research project

The study hypothesis

A hypothesis is a bold statement of what we think the answer to the research question is. Essentially, it is our best guess of what the underlying reality is. As such, it has a pivotal role in any study. The purpose of a research study is to weigh the evidence for and against the study hypothesis. Accordingly, the hypothesis is directly related to the research question.

The study aims

Just as the research question begs the hypothesis, the hypothesis begs the study aims. The examples above demonstrate clearly the natural progression from research question through to the study aims. This is a simple, yet important, process and time spent defining these components will greatly assist in clarifying the study’s objectives. These concepts are discussed more fully elsewhere.1,2

Assembling the research team

All but the smallest of research projects are undertaken as collaborative efforts with the co-investigators each contributing in their area of expertise. Co-investigators should meet the criteria for co-authorship of the publication reporting the study’s findings.3

Usually, the person who has developed and wishes to answer the research question takes the role of principal investigator (team leader) for the project. Among the first tasks is to assemble the research team. Ideally, the principal investigator determines the areas of expertise required for successful completion of the project (e.g. biostatistics) and invites appropriately skilled personnel to join the team.1 It is advisable to keep the numbers within the team to a minimum. In most cases, three or four people are adequate to provide a range of expertise without the team becoming cumbersome. It is recommended that nursing staff be invited to join the team, if this is appropriate. This may foster research interest among these staff, improve departmental morale and may greatly assist data collection and patient enrolment.

Development of the study protocol

The protocol is the blue print or recipe of a research study. It is a document drawn up prior to commencement of data collection that is a complete description of study to be undertaken.4 Every member of the study team should be in possession of an up-to-date copy. Furthermore, an outside researcher should be able to pick up the protocol and successfully undertake the study without additional instruction.

Purpose of the study protocol

Protocol structure

The protocol should be structured largely in the style of a journal article’s Introduction and Methods sections.4 Hence, the general structure is as follows:

Methods

Study design

Study design, in its broadest sense, is the method used to obtain data to prove or disprove the study hypothesis. Many factors influence the decision to use a particular study design and each design has important advantages and disadvantages. For a more extensive discussion on study design the reader is referred elsewhere.1,5

Observational studies

Experimental studies

Types of clinical trials

Concepts of methodology

Validity and repeatability of the study methods

Two types of validity are described:

Study endpoints

Study endpoints are variables that are impacted upon by the factors under investigation. It is the extent to which the endpoints are affected, as measured statistically, that will allow us to accept or reject the hypothesis. For example, a researcher wishes to examine the effects of a new anti-hypertensive drug. It is known that this drug has minor side effects of impotence and nightmares. A study of this new drug would have a primary endpoint of blood pressure drop and secondary endpoints of the incidence of the known side effects.

Sampling study subjects

There are several important principles in sampling study subjects:

Sampling methodology

Stratified sampling

Data-collection instruments

Surveys

Bias and confounding

Study design errors

In any study design, errors may occur. This is particularly so for observational studies. When interpreting findings from an observational study, it is essential to consider how much of the association between the exposure (risk factor) and the outcome may have resulted from errors in the design, conduct or analysis of the study.5 The following questions should be addressed when considering the association between an exposure and outcome:

Systematic error (bias)

Bias in the way a study is designed or carried out can result in an incorrect conclusion about the relationship between an exposure (risk factor) and an outcome (such as a disease) of interest.5 Small degrees of systematic error may result in high degrees of inaccuracy. It is important to note that systematic error is not a function of sample size. Many types of bias can be identified:

Confounding

This is not the same as bias. A confounding factor can be described as one that is associated with the exposure under study and independently affects the risk of developing the outcome.5 Thus, it may offer an alternative explanation for an association that is found and, as such, must be taken into account when collecting and analysing the study results.

Common confounders

Principles of clinical research statistics

Statistical versus clinical significance

This difference is important for two reasons. First, it forms the basis of sample size calculations. These calculations include consideration of what is thought to be a clinically significant difference between study groups. The resulting sample sizes adequately power the study to demonstrate a statistically and clinically significant difference between the study groups, if one exists. Second, when reviewing a research report, the absolute differences between the study groups should be compared. Whether or not these differences are statistically significant is of little importance if the difference is not clinically relevant. For example, a study might find an absolute difference in blood pressure between two groups of 3 mmHg. This difference may be statistically significant, but too small to be clinically relevant.

Databases and principles of data management

The fundamental objective of any research project is to collect information (data) to analyse statistically and, eventually, produce a result or report. Data can come in many forms (laboratory results, personal details) and is the raw material from which information is generated. Therefore, how data are managed is an essential part of any research project.4

Defining data to be collected

Data entry

Data entry can be achieved in many ways:

Research ethics

If one accepts that clinical trials are morally appropriate, then the ethical challenge is to ensure a proper balance between the degree of individual sacrifice and the extent of the community benefit. However, it is a widely accepted community standard that no individual should be asked to undergo any significant degree of risk regardless of the community benefit involved, that is the balance of risks and benefits must be firmly biased towards an individual participant. According to the Physician’s Oath of the World Medical Association ‘concern for the interests of the subject must always prevail over the interests of science and society’.

Informed consent

Controversies and future directions

1 Taylor DMcD. Practical issues in the design and execution of an emergency medicine research study. Emergency Medicine. 1999;11:167-174.

2 Hall GM, editor. How to write a paper, 2nd edn, London: British Medical Journal Publishing, 1999.

3 Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals. Available http://www.jama.ama-assn.org/info/auinst_req.html (accessed March 2002)

4 Good Research Practice Committee. A guide to good research practice. Melbourne: Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, 2001.

5 Jekel JF, Katz DL, Elmore JG, editors. Epidemiology, biostatistics, and preventive medicine, 2nd edn, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2001.

24.2 Writing for publication

Manuscript preparation

Original research manuscripts

Methods

Results

It is important for the results to be presented logically and for the relationships with the objectives and methods to be obvious. A useful structure is to start by describing the study population. This should include how it was derived (a summary figure such as a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram may be very effective for this) and its features such as gender, age, and so on.

Discussion

Manuscript submission

The cover letter

The cover letter is also an opportunity to alert the editor to other issues that may be important. For example, if the manuscript overlaps with previously published work or another manuscript such that there might be a possibility of redundant publication, it allows the editors to assess any overlap for themselves. Alternatively, it also provides the opportunity to identify potential reviewers that the authors believe should be avoided, usually because of actual or perceived conflicts of interest.

24.3 Principles of medical education

Introduction

George Bernard Shaw famously quipped, ‘He who can, does. He who cannot, teaches’. However, the emergency physician can rarely teach without doing. The tradition for doctors to teach their colleagues and students goes back to the Hippocratic Oath, where the duties of a doctor to students are outlined: ‘… to teach them this art, if they want to learn it, without fee or indenture’.1

The emergency environment is one of constant new learning experiences while at the same time being the location for patient care and critical decision-making. Barriers to teaching in hospitals in general, but applicable to emergency departments (ED), have been summarized by Lake in her ‘Teaching on the Run’ series as lack of time, lack of knowledge, lack of training in teaching, criticism of teaching when given, and lack of rewards, either materially or by recognition.1

In addition, teaching in the pressure cooker environment of an ED gives further layers of difficulty, both logistically and ethically. Challenges include:

The ED is a teaching environment, not only for physicians at various levels, but also for nurses, allied health workers, paramedics and others. A significant component of ED teaching is procedural. It is suggested that most patients believe they should be informed if it is the first time a doctor is performing a procedure on them, but less than half of patients feel comfortable about themselves being the first patient ever for suturing (49%), intubation (29%) or lumbar puncture (15%) for a resident.3 For non-procedural medicine the evidence is that most patients enjoy being part of the teaching process, in outpatient and ambulatory settings at least, and that no extra negative effects on patients occur from teaching.4,5

An added component of complexity in teaching in the ED is the potential for slowing patient processing by having to stop and supervise a junior. It is often so much quicker just to do it yourself. Supervising a lumbar puncture, for example, may take both the teacher and the taught away from seeing new patients for half an hour. However, as far as it has been researched, teaching in academic EDs does not appear to slow down patient care but in fact improves quality of care.6 Doctors who are seen by their juniors as good teachers are just as likely to see as many patients per shift as those who are not.7

ED crowding can be seen to have positive and negative effects on emergency teaching. On the one hand, if crowding is due to patients staying for longer periods of time, it may provide increased patient contact and teaching opportunities over that time. On the other, the emergency doctors may have less time for teaching if the crowding is due to increased throughput and production pressure is high.8

All emergency physicians are teachers at some stage in their career at various levels, and, as in Hippocrates’ time, are mostly unpaid for it. Although most doctors become teachers, the majority of prevocational doctors in Australia have had no exposure to learning how to teach.9 Here we present the principles of teaching and learning to assist emergency physicians, whether they are involved with medical students, residents, registrars or other health professionals.

Adult learning principles

Malcolm Knowles first introduced the notion of andragogy or adult learning in the early 1970s.10 He described five assumptions regarding how adults learn:

Knowles and other authors have since developed principles of adult learning that can be used to guide education activities:11–15

However, these principles of adult learning are irrelevant to the emergency physician educator unless they are actively applied to the education of their postgraduate charges. The question remains of how these principles are put into practice. Table 24.3.1 outlines some examples of how these principles may be incorporated into education within the ED.

Table 24.3.1 Application of Adult Learning Principles and Assumptions in the ED environment

1 Schön, D. (1983) The Reflective Practitioner. How professionals think in action, London: Temple Smith.

Learner-centred education

Many traditional medical education experiences are teacher-centred. The teacher is the expert and determines what, how, when and where much is learnt. The teacher is the active participant and the learner is the passive recipient.16 However, a more effective approach to education is the learner-centred approach. Learner-centred education refers to educational events that place the learner in the pivotal position, responsible for determining learning objectives, actively engaging in learning opportunities and participating in evaluation.17 This is more in line with adult learning principles.

What makes a good ED teacher?

The challenges facing the emergency physician educator, including environmental, patient characteristics, administrative and production imperatives and resource availability, cannot be overstated. However, despite this, there is a consistent commitment to education by emergency physicians. What then makes a good ED teacher? Bandiera and colleagues used a qualitative research design to investigate experienced ED teachers and establish the behaviours that made them good teachers.2

Twelve strategies were identified:

Types of teaching in the ED

‘Trolley-side’ teaching

Interactions with patients at the bedside are a crucial component for learning in medicine, the traditional apprenticeship model relying on this methodology. Bedside teaching can provide an opportunity for the experienced clinician to explain clinical reasoning and role model appropriate communication, including listening, patient questioning and respect, supervising the more junior clinicians as they practise these skills, assessing the junior clinicians’ interaction with the patient and providing feedback to them.19 However, with the numerous environmental constraints within the ED there is a need to look at bedside teaching and determine how best to conduct this activity. In addition, the care of the patient remains paramount and ensuring that this is maintained and that the junior doctor–patient relationship is not undermined is an additional challenge.

Procedural skill teaching

Management of patients in the ED often involves the practitioner performing procedural skills. Some of these are to assist in formulating diagnoses in the undifferentiated patient, for example performance of bedside ultrasound, others are for treatment of patient conditions, for example application of a plaster to a fracture. Ideally, in this day and age, procedural skills should be practised in a clinical skills setting prior to implementation on a ‘real’ patient.22 However, observation by a junior doctor of an experienced clinician performing a task is also valuable and can sometimes be overlooked in the busy ED department. Sometimes it is done before you realize you could have shown a junior doctor.

The educational theories relevant to teaching clinical skills are drawn from psychomotor theories. There are seven basic principles of the psychomotor domain,23 including:

Similarly, Gagne24 describes three phases in instructional design relevant to teaching a technical skill, including a cognitive phase where the learner is developing cues from the facilitator, an associative phase where the learner is integrating the component parts and an autonomous phase where the skill has become automatic for the learner.

The issue of the relationship of the learner to the experienced clinician is further investigated within the cognitive apprenticeship model.25,26 The emphasis in this model is on the requirement that the thinking of the expert be made visible and brought to the surface for the learner. Underpinning this model is the ability of the teacher to assess/recognize the level of the learner.

Another debate in the literature is around the issue of whole skill training versus part skill training. Evidence would suggest that the part skill training method be used for the more complex skills while whole skill training be used for the relatively straightforward skills. This requires the facilitator to analyse the skills to be taught and determine the level of complexity of that specific skill. Additionally, what is the whole skill? It can be argued that procedural skills do not occur in isolation. Rather, communication skills are required along with the technical expertise, and should be taught together rather than in isolation to reflect the requirement in reality.27,28

Simulation

Simulation is an emergent teaching methodology within the ED environment. In its broadest sense it refers to any situation in which the real situation is emulated. It may involve actors playing the role of patients, who are often described as standardized patients, or manikins with computer-generated physiological responses.29,30

The underpinning educational theory behind simulation comes from a number of theories, including adult learning. However, experiential learning theory is probably of most relevance. Experiential learning theory as espoused by Kolb31 describes experiential learning activities as opportunities for learners to acquire and apply knowledge, skills and attitudes in an immediate and relevant setting. A four-point continuous learning cycle is described:

There are a number of ways in which ED physicians can incorporate simulation opportunities into their teaching in ED. It may be that paper-based simulations are used to explore clinical reasoning. This involves developing case scenarios and structured questions. Role-playing, using peers or expert clinicians, can be used to practise difficult communication skills such as breaking bad news. Simple part-task trainers can be incorporated into a more complex scenario involving the practice of the skill whilst interacting with a patient. Kneebone and colleagues28 describe integrating a urinary catheter manikin with an actor to ensure that the technical and communication skills are taught concurrently.

Not all EDs have the luxury of the highly technical simulation ‘gadgetry’, but this should not put them off using simulation as a teaching methodology. Determining the content areas appropriate for using simulation and how this fits into the overall curriculum will be important to ensure that resources are used rationally.32

Feedback to learners

Feedback is a crucial requirement for learning, and the importance of positive feedback for learning has been well established.33 Feedback should provide the learner with information that offers ‘insight into what he or she did as well as the consequences of his or her actions’.34 It should allow the learner to know what went well and what could be improved or changed next time. Feedback is part of the formative assessment process that occurs throughout the learning period, rather than as a summative assessment that is to determine a grade or make a final judgment.

Effective feedback has a number of characteristics.35,36 It should be given in a suitable environment to allow privacy and maintain confidentiality for the learner. There should be adequate time to allow the learner and the facilitator to explore the observed behaviour or skill. There should be clear goals established at the beginning of the learning so that feedback can be related to these goals. The feedback should come from direct observation of the learner’s performance where possible.

Providing learners with feedback is a specific skill in itself and requires practise to develop. A model to assist the emergency physician to give feedback is suggested from Pendleton’s37 work as:

Likely developments over the next 5–10 years

1 Lake FR. Teaching on the run tips: doctors as teachers. Medical Journal of Australia. 2004;180(8):415-416.

2 Bandiera G, Lee S, Tiberius R. Creating effective learning in today’s emergency departments: how accomplished teachers get it done. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2005;45:253-261.

3 Santen S, Hemphill R, McDonald F, et al. Patients’ willingness to allow residents to learn to practice medical procedures. Academic Medicine. 2004;79:144-147.

4 Simons R, Imboden E, Mattel J. Patient attitudes toward medical student participation in a general internal medicine clinic. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1995;10(5):251-254.

5 Simon S, Peters A, Christiansen C. Effect of medical student teaching on patient satisfaction in a managed care setting. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15(7):457-461.

6 Berger TJ, Ander DS, Terrell ML, et al. The impact of the demand for clinical productivity on student teaching in academic emergency departments. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2004;11:1364-1367.

7 Denninghoff KR, Moye PK. Teaching students during an emergency walk-in clinic rotation does not delay care. Academic Medicine. 1998;73:1311.

8 Atzema C, Bandiera G, Schull MJ. Emergency department crowding: the effect on resident education. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2005;45:276-281.

9 Dent AW, Crotty B, Cuddihy H, et al. Learning opportunities for Australian prevocational hospital doctors: exposure, perceived quality and desired methods of learning. Medical Journal of Australia. 2006;184:436-440.

10 Knowles M. The adult learner: a neglected species. Houston: Gulf Publishing, 1973.

11 Cantillon P, Hutchinson L, Wood D. ABC of learning and teaching in medicine. London: British Medical Journal Publishing, 2003.

12 Knowles M. The modern practice of adult education: from pedagogy to andragogy, 2nd edn. New York: Cambridge Books, 1980.

13 Kaufman D, Mann K. Teaching and learning in medical education: How theory can inform practice. Edinburgh: Association for the Study of Medical Education, 2007.

14 Peyton J. Teaching and learning in medical practice. Great Britain: Manticore Europe, 1998.

15 Brookfield S. Understanding and facilitating adult learning. Buckingham: Open University Press, 1986.

16 Gunderman R, Williamson K, Frank M, et al. Learner-centered education. Radiology. 2003;227:15-17.

17 Weimer M. Learner centred teaching. New York: Jossey-Bass, 2002.

18 Thurger L, Bandiera G, Lee S. What do emergency medicine learners want from their teachers? A multicentre focus group analysis. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2005;12:856-861.

19 Celenza A, Rogers I. Qualitative evaluation of a formal bedside clinical teaching programme in an emergency department. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2007;23:769-773.

20 Lake F, Ryan G. Teaching on the run tips 4: Teaching with patients. Medical Journal of Australia. 2004;181:158-159.

21 Wolpaw T, Wolpaw D, Papp K. SNAPPS: a learner centred model for outpatient education. Academic Medicine. 2003;78:893-898.

22 De Young S. Teaching psychomotor skills. In: Teaching strategies for nurse educators. United Kingdom: Prentice Hall Health; 2003:201-215.

23 George J, Doto F. A simple five-step method for teaching clinical skills. Family Medicine. 2001;33:577-578.

24 Gagne R. The conditions of learning, 4th edn. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1985.

25 Collins A, Brown J, Newman S. Cognitive apprenticeship: teaching the crafts of reading, writing and mathematics. In: Resnick L, editor. Learning and instruction: essays in honor of Robert Glaser. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1989:453-494.

26 Woolley N, Jarvis Y. Situated cognition and cognitive apprenticeship: a model for teaching and learning clinical skills in a technologically rich and authentic learning environment. Nurse Education Today. 2007;27:73-79.

27 Kneebone R, Kidd J, Nestel D, et al. An innovative model for teaching and learning clinical procedures. Medical Education. 2002;36:628-634.

28 Kneebone R, Nestel D, Yadollahi F, et al. Assessing procedural skills in context: exploring the feasibility of an integrated procedural performance instrument (IPPI). Medical Education. 2006;40:1105-1114.

29 Ker J, Bradley P. Simulation in medical education. Edinburgh: Association for the Study of Medical Education, 2007.

30 Good M. Patient simulation for training basic and advanced clinical skills. Medical Education. 2003;37(suppl):14-21.

31 Kolb D. Experiential learning. Englewood Cliffs. NJ: Prentice Hall, 1984.

32 Binstadt E, Walls R, White B, et al. A comprehensive medical simulation education curriculum for emergency residents. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2007;49:495-504.

33 Kilminster S, Jolly B, van der Vleuten C. A framework for effective training for supervisors. Medical Teacher. 2002;24:385-389.

34 Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. American Medical Association. 1983;250:777-781.

35 Schwenk T, Whitman N. The physician as teacher. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1987.

36 Vickery A, Lake F. Teaching on the run tips 10: Giving feedback. Medical Journal of Australia. 2005;183:267-268.

37 Pendleton D, Schofield T, Tate P, et al. The consultation: an approach to teaching and learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984.

24.4 Undergraduate teaching in emergency medicine

Introduction

Emergency medicine now plays a central role in medical curricula in undergraduate and postgraduate medical schools in Australia and New Zealand. This is not unexpected, as the principles and practice of the specialty have much in common with contemporary medical education: it is problem-focused, interdisciplinary, and integrates many aspects of community-based and hospital-based clinical practice. Clinical practice easily integrates and builds upon the basic medical sciences traditionally taught early in the medical course. Much growth in academic emergency medicine has occurred in the last 10 years, with the establishment of academic departments and dedicated university positions. However, the majority of medical student teaching is performed by emergency physicians in clinical practice in public, and an increasing number of private, emergency departments (EDs).This chapter will address the issues surrounding medical student teaching at the departmental and the broader faculty level.

Overview of undergraduate medical education in Australia

It is important for emergency physicians interested in teaching medical students to be aware of recent trends and developments in medical education in Australasia. The last 15 years have seen the establishment of graduate schools of medicine and a massive reform of the traditional undergraduate curricula. The CanMEDS 2000 Project and the World Health Organization, among others, have listed the key outcomes expected of a doctor.1 These outcomes have been adopted by many schools worldwide as a basis for reform and reorganization, and are listed in Table 24.4.1. In more detail, the Australian Medical Council has listed 40 attributes of medical graduates to guide faculties with curriculum design and subsequent accreditation.2 Many schools have organized their curricula into themes, or domains, so that these outcomes can be vertically integrated, tracked and assessed throughout the course. Some schools have adopted problem-based learning as a tool to achieve these educational outcomes, with others using case-based and outcomes-based learning to place content in a clinical context.

Table 24.4.1 Essential roles and key competencies of specialist physicians – The CanMEDS criteria1

| Medical expert |

| Communicator |

| Collaborator |

| Manager |

| Health advocate |

| Scholar |

| Professional |

These changes have not been without controversy, with some critics concerned that this has been at the expense of basic science teaching and the teaching of sound clinical practice.3 Curriculum reform has occurred in parallel with significant changes in the health system, with a growth in information technology, changing patient expectations and a massive increase in medical knowledge. Models of healthcare delivery are changing, with increased pressures on public hospitals such as access block, declining numbers of inpatient beds and the increasing complexity of medical conditions. The shift to the home and community management of many conditions has altered the patient mix available for student teaching. University salaries have not kept pace with the growth in public and private medical salaries, which has contributed to a decline in numbers of academic faculty and core medical school functions shifting to specialists within the public hospital system. Despite this, there has been an increasing number of medical students and medical schools, with over 3000 graduates per year predicted to require intern posts by the middle of the next decade.4 It is in this changing environment that emergency medicine has established itself as a key part of any modern medical curriculum. With a growing number of medical students, emergency physicians and patients, the specialty is poised to play an even greater role in the training of future doctors. Both the need and the opportunity exist for such expansion.

The importance of medical student teaching

This is an important point to consider, as many feel that the provision of clinical care is the core business of an ED and hence may not be willing to allocate resources for teaching students. Similarly, university medical schools may not be aware of the growth of emergency medicine as a specialty and hence may not be aware of what it can offer students. However, once established, a strong academic presence can contribute to departmental morale and performance. Table 24.4.2 lists the benefits of emergency medicine teaching to students, EDs and medical schools. These points may be used to argue for an increased presence and accompanying resources within a curriculum.5 Resources and a formal place in the curriculum often come only after years of hard work in establishing the bona fides of emergency medicine. This may require much time and effort from a dedicated individual.

Table 24.4.2 Benefits of medical student teaching in emergency departments

| Benefits to students |

Curriculum development

Medical student teaching in EDs has, until recent years, been largely a passive and opportunistic affair. Inpatient units would send groups of hapless students ‘down to “cas”’ to see if there was ‘anything interesting going on’. As such, exposure to emergency medicine was ad hoc, unstructured and highly selective, in that clinical exposure was based around what the students themselves thought was interesting and useful. With the growth of the specialty in recent years departments have been able to take a more active role in education, control student entry to the department, ensure appropriate orientation and attempt to take advantage of the rich and broad clinical experience on offer. As faculties have become aware of the learning opportunities on offer in EDs, as well as the teaching abilities of staff, emergency physicians have been able to negotiate a greater role in university affairs and integrate emergency medicine into the broader undergraduate curriculum. With this comes a responsibility for emergency physicians to understand the function of universities, and the requirements which come with running an academic term. Table 24.4.3 provides suggestions for developing a university teaching presence.

Table 24.4.3 Minimum requirements for developing student placements in emergency departments

It is essential that once a department has decided that medical student teaching should be a part of its function then a curriculum needs to be considered. Both the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine and the American College of Emergency Physicians have produced documents with varying degrees of detail concerning this,6,7 and a growing number of papers are being published providing guidance to curriculum developers.8–10 Most core curriculum statements contain elements which reflect the clinical practice of emergency medicine, and an example of such a list is provided in Table 24.4.4. This provides a framework around which specific topics can then be taught. The teaching programme will need to be modified and adapted accordingly depending upon the expertise of and time available to specialists within the department.

Table 24.4.4 Suggested core curriculum topics in emergency medicine

Different ways to teach emergency medicine

In all formats, teachers should consider the basic principles of adult learning and teach accordingly. When delivering material, teachers should remember that adults learn best when the topic is meaningful, linked to experience and pitched at the correct level, and the students are motivated, have clear goals, are actively involved, receive regular feedback and have time for reflection.11 Utilizing a range of methods means that material can be delivered in a meaningful way and optimal learning conditions can be achieved. It is essential that the physician taking responsibility for undergraduate teaching within a department takes a leadership role and provides ongoing training and support for both junior and senior colleagues in effective teaching methods.

Whichever teaching method is chosen, evaluation of the process by the participants is an essential part of the quality improvement cycle. This may be in the form of a brief questionnaire or standardized form, such as a part of a student evaluation of teaching and learning (SETL) programme. Evaluation helps ensure teaching is meeting students’ learning needs, identifies areas where teaching can be improved, and provides feedback and encouragement for teachers.12 Documenting evaluations can form part of a teaching portfolio, which can be used in academic job applications as tangible evidence of a clinician’s commitment to and proficiency in teaching. Importantly, from a student’s perspective, being asked to evaluate a teaching session and then seeing the comments acted upon provides a strong sense that their participation is valued and as a result may improve the learning process overall.

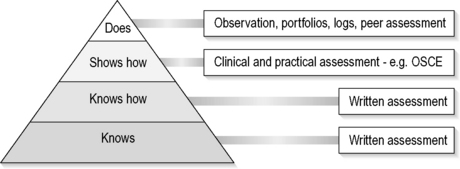

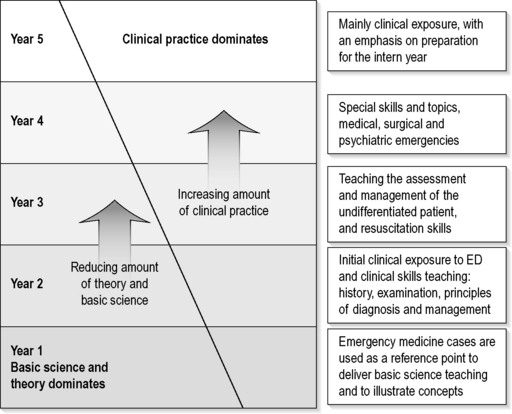

Some basic pedagogical theory should be considered when choosing and applying methods of teaching: many educators refer to Miller’s triangle of clinical competence13 and the concept of a spiral curriculum14 when designing curricula. Figure 24.4.1 is a schematic representation of how emergency medicine as a subject could ideally progress through a 5-year course utilizing these theories of curriculum design. Most departments will only be in a position to offer clinical exposure in the final years of the course, but much progress has been made across the region in penetrating all years. The following delivery methods could be used in this framework to deliver a comprehensive and effective emergency medicine curriculum.

Fig. 24.4.1 A suggested overview of the progression of emergency medicine in an integrated 5-year curriculum.

Lecture based

Lectures can be delivered at any stage of the medical course, but to maximize their effectiveness they need to be developed in an integrated fashion and linked to other components of the course. Emergency medicine can be used effectively as a vehicle to illustrate basic science concepts to junior medical students.15 Case-based learning is a popular method to use in this setting, as learning objectives and concepts can be illustrated in a ‘real-world’ setting. For example, rather than delivering a lecture on ischaemic heart disease, an emergency medicine lecture would be entitled ‘I’ve got pain in my chest’ and the lecturer would engage with students to create a genuine feel for this common emergency presentation. The content would need to be modified depending upon the seniority of students, for example junior medical students would use the case as a reference point to illustrate anatomy and physiology, whilst more senior students may use the same scenario to learn about clinical decision making and evidence-based medicine.

Lectures need not be didactic and overloaded with content – they can be an efficient means of transmitting information to large groups. In general, lectures should add value. There is little point simply repeating content from a text, as students can gather information themselves in their own time. In this sense, prospective lecturers should remind themselves of the qualities of an effective educator: expertise in the subject area, enthusiasm for the topic and the task, and capacity to engage the learners.16 By utilizing these qualities, educators can turn a lecture into a valuable learning experience.

Web-based

This is growing in popularity as schools rely more on information technology to deliver content, but few emergency physicians have had the time or the access to moderate and upload content and hence maximize the opportunities this mode of teaching can present. At a basic level, bulletin boards, web logs (blogs) and email are useful ways to maintain regular communication with students and to distribute journal articles and policies, and orientation manuals can be posted online.17

However, with faster internet conditions and a new generation of students increasingly familiar with technology, new opportunities are appearing: virtual worlds and the operation of a ‘Second Life’ ED (http://secondlife.com) may become useful tools for education.

Work-based

This is the original method of medical student education: at the bedside of the patient. Medicine has been taught this way for thousands of years, and reinforces the point that medical students are essentially apprentices in a trade. Emergency medicine excels in this area because of the broad range of experiences on offer in a department. Challenges exist, as not all students will be exposed to the same conditions during a rotation. Achieving a uniform experience for students is difficult,18 and so workbooks have been developed to guide students through their rotation, alerting them to the broad range of undifferentiated conditions which regularly present. Utilizing junior staff can be helpful in the education of medical students: pairing a student with a resident or registrar allows the students to see how a doctor works, and it involves junior doctors in teaching at an early stage of their careers. It helps with rostering, in that students can be allocated to medical staff with a pre-existing timetable. Medical schools offer clinical academic titles to doctors involved in teaching, and all staff should be encouraged to apply for such titles.

Teaching by the bedside is an important activity and opportunities abound for clinical teaching. Clinicians being aware of a broader curriculum can be of assistance, as it can be difficult to think on the spot when confronted with a ‘teachable moment.’ Some guidelines exist to maximize the value of bedside teaching and the well-developed principles of ‘set, dialogue and closure’19 are explained and listed with an example in Table 24.4.5.

| Concept | Components | Example in practice |

|---|---|---|

| Set |

You have just assessed a young male with a severe headache. You realize that this is an ideal teaching opportunity for the medical students present.

Simulation

Simulation is a growing field which has been embraced by emergency physicians and the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine. A large knowledge base has been developed, and as such it will not be discussed at length here. However, the main barrier to utilizing simulation for undergraduate teaching is cost and the available time of emergency physicians. Fortunately, universities are starting to recognize the value of this method of teaching and opportunities are being created.

Clinical skills teaching

Emergency medicine has long had a reputation amongst students for ‘being the place where you get to do useful things’. Whilst proponents of the specialty in universities are keen to promote the other features of emergency medicine in an educational setting, this statement is still undoubtedly true. Many skills can be taught in the ED or a skills laboratory, and emergency physicians are ideally placed to teach them. Whether it is junior medical students examining patients for the first time or learning practical skills such as venesection and suturing, emergency physicians have a lot to offer in this regard. Like most teaching, there are useful techniques that can be employed to improve learning.20

Assessment principles

Assessment should be considered as a tool which drives learning, and should be developed in parallel with the curriculum rather than considered at the end. It is essential that the appropriate form of assessment be matched to the subject matter. Assessment tools selected should be valid, reliable and practical, and have an appropriate impact on student learning.21 For instance, when assessing competency in advanced cardiac life support, it would be more valid to use a practical-based assessment process such as an observed objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) rather than a written examination. Figure 24.4.2 provides a graphical representation of matching assessment processes to skills and knowledge. A large number of assessment methods exist and educators should possess at least a basic understanding of their use and application. It is essential to understand that all universities have rules which govern the assessment of students, and failure to strictly adhere to these rules exposes a department to academic appeals and complaints of unfairness and bias.

Likely developments over the next 5–10 years

It is now time for the specialty to move beyond just the provision of training in acute medicine as envisaged by the landmark Macy report in 1994.22 The specialty will develop its own body of knowledge and curriculum in important but under-represented areas of medical education such as clinical decision-making, medical error and health systems design and management. Emergency physicians need to take a leading role in the development and delivery of curricula in these areas. There is much to suggest that the increased sub-specialization of medicine has led to fragmentation of the health system, with the subsequent inability of society to achieve coherent and sustainable outcomes in health policy. Emergency medicine as a specialty has the opportunity to take a leading role in training doctors and other health professionals capable of understanding the key challenges facing the health system in the 21st century.

1 The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Can MEDS 2000 Project skills for the new millennium. Ontario: Report of the societal needs working group, 1996.

2 Australian Medical Council. Goals and objectives of basic medical education. http://www.amc.org.au/GoalsBasicMed.asp. (accessed 13 August 2007)

3 Van der Weyden M. Medical education and hard science. Medical Journal Association. 2003;180(12):601.

4 Crotty B, Brown T. An urgent challenge: new training opportunities for junior medical officers. Medical Journal Association. 2007;186(7):S25-S27.

5 Russi CS, Hamilton GC. A case for emergency medicine in the undergraduate medical school curriculum. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2005;12(10):994-998.

6 Australasian College for Emergency Medicine. Policy on the emergency medicine component of the undergraduate medical curriculum. http://www.acem.org.au. (accessed 13 August 2007)

7 ACEP Academic Affairs Committee. Guidelines for Undergraduate education in emergency medicine. http://www.acep.org/webportal/PracticeResources/issues/acad/prepemundergradguideeduc.htm. (accessed 9 August 2007)

8 Task Force on National Fourth Year Medical Student Emergency Medicine Curriculum Guide. Report of the Task Force on National Fourth Year Medical Student Emergency Medicine Curriculum Guide. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2006;47:E1-E7.

9 Pacella CB. Advanced opportunities for student education in emergency medicine. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2004;11(10):9-12.

10 Coates WC, Gendy MS, Gill AM. Emergency medicine subinternship: Can we provide a standard clinical experience? Academic Emergency Medicine. 2003;10:1138-1141.

11 Lake F, Ryan G. Teaching on the run tips 2: educational guides for teaching in a clinical setting. Medical Journal Association. 2004;180(10):527-528.

12 Morrison J. ABC of learning and teaching in medicine: evaluation. British Medical Journal. 2003;326:385-387.

13 Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Academic Medical Journal. 1990;65:563-567.

14 Harden RM, Stamper N. What is a spiral curriculum? Medical Teacher. 1999;21:141-143.

15 Walls J, Couser GA, Gennat H, et al. Clinical cases in emergency medicine: a physiological approach. Sydney: McGraw-Hill, 2006.

16 Arnold R. The theory and principles of psychodynamic pedagogy. Forum of Education. 49(2), 1994.

17 McKimm J, Jollie C, Cantillon P. ABC of learning and teaching: web based learning. British Medical Journal. 2003;326:870-873.

18 Coates WC, Gendy MS, Gill AM. Emergency medicine subinternship: can we provide a standard clinical experience? Academic Emergency Medicine. 2003;10:1138-1141.

19 Lake F, Ryan G. Teaching on the run tips 3: planning a teaching episode. Medical Journal Association. 2004;180(12):643-644.

20 Lake F, Hamdorf J. Teaching on the run tips 5: Teaching a skill. Medical Journal Association. 2004;181(6):327-328.

21 Shumway JM, Harden RM. AMEE Guide No. 25: The assessment of learning outcomes for the competent and reflective physician. Medical Teacher. 2003;6(25):569-584.

22 Josiah MacyJr. The role of emergency medicine in the future of American medical care. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1995;25:230-233. Foundation

24.5 Postgraduate emergency medicine teaching and simulation

Introduction

Emergency departments (EDs) provide many learning opportunities for postgraduate doctors. The varied clinical case mix, procedural nature of practice and flexibility of work attract doctors to vocational training. Postgraduate emergency medicine teaching has traditionally followed an apprenticeship model, with the underlying assumption that patient care experience and opportunistic bedside teaching from clinical experts provided the knowledge, skills and attitudes requisite for emergency medicine practice. This model is currently being challenged by contemporary workforce issues, changed service provision models, improved technology and advances in medical education.

Current training pathways in postgraduate emergency medicine

In those countries where emergency medicine has been recognized as a specialty, with a model and scope of practice, formalization of postgraduate training has followed. In Australasia, Canada, South Africa and the UK, specialist colleges have been responsible for accreditation and standards for emergency medicine training.1–3 The American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM)4 in the USA fulfils a similar role. In other jurisdictions, tertiary institutions (Malaysia) or professional societies (many European countries) provide the educational framework for vocational training.

These formal training programmes provide a structured educational experience for vocational trainees. The length of training varies from 3 to 7 years, generally uses graduated patient care responsibility as the primary learning experience, and requires a range of rotations through emergency medicine and other clinical experience such as anaesthesia, intensive care, psychiatry and paediatrics.5 Most programmes involve both in-training assessment and formal examinations during the period of training. Many programmes also require logbooks or portfolios of clinical experience.

The regulatory frameworks continue to evolve. The UK has recently reconfigured postgraduate training in the ‘Modernising Medical Careers’ initiative,6,7 resulting in the NHS taking on roles previously held by specialist colleges. In Australia there are calls for shorter ‘non-specialist’ training programmes for career emergency doctors, particularly to address rural and regional workforce challenges.8 In developing countries, there is variable progress toward formal postgraduate training.

Challenges for contemporary emergency medicine education

There are growing pressures on postgraduate medical education in emergency medicine (Table 24.5.1). The impact of these trends can be observed in emergency medicine curricula, teaching and learning processes, learning technology, assessment and accreditation, and faculty development.

Table 24.5.1 Pressures leading to change in delivery of postgraduate education in emergency medicine

Curricular trends

The CanMEDS model, developed in Canada and adopted by the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine (ACEM), requires training be oriented toward preparing emergency physicians (and other specialist trainees) for their roles as medical expert, communicator, collaborator, manager, health advocate, scholar and professional.10

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in the USA defines six core competencies required of specialist trainees: medical knowledge, patient care, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice. These general competencies have been translated into specific emergency medicine curricular objectives.11

Integral to this curricular trend has been increased recognition of communication and professional domains of practice. Concepts of teamwork, leadership, patient safety, quality improvement, and communication with patients and peers have been specified in recent curricula.12 New domains of learning, such as medical informatics and evidence based medicine, have become explicit curricular content.

Innovation in teaching and learning

Reflective practice is an important learning skill for postgraduate trainees. Clinical audit13 and portfolios14 can facilitate this, and most training programmes also encourage participation in critical incident review, trauma review meetings and morbidity and mortality rounds.

Recent innovations in training incorporate interprofessional and team-based learning, following recognition of the team approach required for effective clinical practice. This includes multidisciplinary formal educational sessions and team-based simulation experiences.15 Such activities are focused on communication and professional domains of competence, and provide trainees with a broader perspective on systems-based practice in emergency medicine.

Learning technology

Web-based content for emergency medicine has exploded over recent years. A Google search for ‘emergency medicine’ reveals more than 64 million web pages. As a result, the emergency medicine trainee requires effective information retrieval and quality analysis skills. Recent literature suggests that public access search engines such as Google Scholar have now replaced traditional Medline database searches as the preferred method of information retrieval by trainees.16

Procedural skill training has been enhanced by the use of manikins, part trainers, and virtual reality systems,17 reducing the use of animal labs and cadavers. There is evidence that this approach is more effective than traditional procedural skills training on patients.18 Video-based instruction of procedures allows demonstration of procedural performance under ideal conditions, with rehearsed teaching scripts. Many of these are now available on personal digital assistants for ‘just-in-time learning’ for trainees. More comprehensive e-learning packages for procedural skills training use a problem-based approach, informed by known complications and high risk situations, and often complemented by hands-on sessions.19

The internet has also provided opportunities for the formation of virtual learning communities in emergency medicine. Informal discussion boards and weblogs foster collaborative networking and debate. Formal training activities can also be conducted via asynchronous learning networks,20 and specialized software platforms can enhance interactivity and promote user-generated content for more active e-learning experiences.21

Videoconferencing and tele-education have sought to answer the challenges of distance in emergency medicine education.22 This technology has been successfully employed in the continuing medical education (CME) arena,23 but improvements in technology and bandwidth potentially provide greater access to interactive educational activities at all levels of emergency medicine training. It may help to relieve the teaching workload in smaller or more remote EDs.

Simulation-based learning for emergency medicine

Medical simulation encompasses any kind of simulated patient interaction, manikin or virtual-reality-based procedural skill performance, or simulated complex emergency medicine scenario. It involves technology as simple as standardized human patients with a role play script, and as complex as high fidelity simulators designed to provide realistic tactile, auditory and visual stimuli. The varied dimensions of simulation and its wide application to professional practice offer potential solutions to many healthcare educational challenges.24

Simulators, equipment and fidelity

Manufacturers have classified manikins as high or low fidelity based on their technological complexity. However, the fidelity of the simulation experience as perceived by the learner is far more complex. The authenticity of the scenario presented, including clinical, professional and communication challenges, the realism of the team composition and the physical environment all appear to be more important to both the learners’ perception of fidelity and the learning outcomes achieved.25,26

Teamwork and communication skills training using medical simulation

Crisis resource management (CRM) training in emergency medicine using human patient simulation27 draws on parallels between acute patient care and the aviation and military industries, where it has been recognized that human factors are crucial to team performance.

A typical scenario might involve a team of medical and nursing participants managing a man with chest pain, who is accompanied by his wife in the ED, and who then develops a life-threatening arrhythmia. Participants need to identify and manage clinical issues, while engaging in the communication, teamwork and leadership activities inherent in real clinical practice. The scenario is then followed by video-assisted, expert debrief to reflect upon individual and team performance. This experiential learning approach enables cross-domain training in which cognitive, procedural and affective domains of practice are authentically integrated. The interprofessional nature of the learning experience provides a unique opportunity for increased understanding of the role of other healthcare disciplines.

Evidence for simulation-based learning

Evidence for clinical practice improvement is currently lacking, despite intuitive appeal.28 There are methodological challenges in the reliable measurement of teamwork and communication performance, and attribution issues involved in any demonstration of patient outcome improvement. Professional associations in the field are working towards international consensus on learning objectives, methodology and evaluation.

Assessment and performance appraisal

Trainee assessment formats in formal postgraduate emergency medicine training programmes are diverse. These formats have usually been determined by national training and accreditation bodies (see Chapter 27.5). There is considerable variation in the domains of performance formally assessed, the definition of ‘professional competence’ required and in the standardization of assessment processes undertaken.

In-training assessment by clinical supervisors is a core element in most programmes, but this may be provided by one designated supervisor of training or many clinical supervisors in a group-based assessment. Literature suggests that in-training assessment is a valid tool (i.e. measures the right thing),29 but the potentially subjective nature of supervisor assessments continues to raise questions as to reliability.

Workplace-based assessment is becoming more prevalent, with use of tools such as clinical simulations, portfolios, standardized patients and multisource ‘360 degree feedback’ assessment that involves assessment by patients, peers, nursing staff and others.30 Patient care quality outcomes have been suggested as an assessment tool.31 These formats encourage the trend toward specific assessment of communication and professional competence, which mirror the shift in curricular content.

Faculty development in emergency medicine

Many emergency physicians are enthusiastic clinical teachers. However, there is now recognition that these clinician educators require specific preparation for their teaching role. Specific training for educators in emergency medicine is variable, including Masters level courses, short workshops,32 and institution-based group professional development activities. These courses typically cover topics such as curriculum development, teaching and learning processes, and assessment and feedback skills.

Programmes are more formally developed in the USA, where a number of teaching fellowships exist in emergency medicine and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) has published a Faculty Development Handbook.33 These initiatives have been reinforced by the emergence of ‘clinician educator tracks’ in academic institutions to provide an academic career structure for clinical teachers.

Non-vocational teaching in emergency medicine

Pre-vocational education

In Australasia, the UK and other countries where prevocational doctors exist, the emergency medicine term has been recognized for learning acute care skills, management of the undifferentiated patient, and professional skills such as teamwork and communication. These competencies and domains of learning have been formalized recently in consensus statements such as the Australian Junior Doctor Curriculum Framework.34

Continuing medical education

The effectiveness of current CME offerings, as measured by changes in physician behaviour, appears lacking,35 raising questions about the design and educational value of many of these courses. However, it is recognized that many CME activities also provide a political and social function.

Controversies and future directions

1 Steiner IP. Emergency medicine practice and training in Canada. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2003;168(12):1549-1550.

2 Australasian College for Emergency Medicine. http://www.acem.org.au. Online. (accessed 5 August 2007)

3 College of Emergency Medicine South Africa (CMSA). http://www.collegemedsa.ac.za/view_college.asp?. Online. Type=Link and CollegeID=55 (accessed August 2007)

4 American Board of Emergency Medicine. http://www.abem.org/public/. Online. (accessed 5 August 2007)

5 Taylor DM, Jelinek GA. A comparison of Australasian and United States emergency medicine training programs. Academic Emergency Medicine. 1999;6(4):324-330.

6 How is medical training changing? Modernising medical careers. Online. Available: http://www.mmc.nhs.uk/download/What%20is%20changing%20at%20MMC.pdf (accessed 9 August 2007)

7 McGowan A. Modernising medical careers: educational implications for the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2006;23(8):644-646.

8 Arvier PT, Walker JH, McDonagh T. Training emergency medicine doctors for rural and regional Australia: can we learn from other countries? Rural & Remote Health. 2007;7(2):705.

9 Brooks P, Lapsley H, Butt D. Medical workforce issues in Australia: ‘Tomorrow’s doctors – too few, too far’. Medical Journal of Australia. 2003;179:206-208.

10 JR Frank The CanMEDS 2005 physican competency framework. Better standards. Better physicians. Better care The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada Ottawa. Online. Available http://rcpsc.medical.org/canmeds/CanMEDS2005/index.php (accessed 6 August 2007)

11 Chapman DM, Hayden S, Sanders AB, et al. Integrating the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies into the model of the clinical practice of emergency medicine. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2004;43(6):756-769.

12 Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2004;13:85-90.

13 Brazil V. Audit as a learning tool in postgraduate emergency medicine training. Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2004;16(4):348-352.

14 Cook RJ, Pedley DK, Thakore S. A structured competency based training programme for junior trainees in emergency medicine: the ‘Dundee model’. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2006;23(1):18-22.

15 Shapiro MJ, Morey JC, Small SD. Simulation based teamwork training for emergency department staff: does it improve clinical team performance when added to an existing didactic teamwork curriculum? Quality Safety Health Care. 2004;3:417-421.

16 Giustini D. How Google is changing medicine. British Medical Journal. 2005;331:1487-1488.

17 Vozenilek J, Huff JS, Reznek M, et al. See one, do one, teach one: advanced technology in medical education. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2004;11(11):1149-1154.

18 Seymour NE, Gallagher AG, Roman SA, et al. Virtual reality training improves operating room performance: results of a randomized, double-blinded study. Annals of Surgery. 2002;236(4):458-464.

19 Med-e-serv. Insertion of chest tubes and management of chest drains in adults. Online. Available: http://learning.medeserv.com.au/products/MES2020/MES2020_brochure.cfm (accessed 14 August 2007)

20 Ashton A, Bhati R. The use of an asynchronous learning network for senior house officers in emergency medicine. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2007;24(6):427-428.

21 Moodle. Online. Available: http://moodle.org/ (accessed August 16 2007)

22 Sweetman G, Brazil V. Education links between the Australian rural and tertiary emergency departments: Videoconference can support a virtual learning community. Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2007;19(2):176-177.

23 Allen M, Sargeant J, Mann K, et al. Videoconferencing for practice-based small group continuing medical education: feasibility, acceptability, effectiveness, and cost. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2003;23:38-47.

24 Gaba D. The future vision of simulation in health care. Quality and Safe Health Care. 2004;13:2-10.

25 Rehmann A, Mitman R, Reynolds M. A handbook of flight simulation fidelity requirements for human factors research. Technical Report No. DOT/FAA/CT-TN95/46 Wright Patterson Air Force Base. Ohio: Crew Systems Ergonomics Information Analysis Centre, 1995.

26 Beaubien JM, Baker DP. The use of simulation for training teamwork skills in healthcare: how low can you go? Quality Safe Health Care. 2004;13:51-56.

27 Reznek M, Smith-Coggins R, Howard S, et al. emergency medicine crisis resource management (EMCRM): pilot study of a simulation-based crisis management course for emergency medicine. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2003;10:386-389.

28 Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa E, et al. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simualtions that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Medical Teacher. 2005;27(1):10-28.

29 Epstein R. Assessment in medical education. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356:387-396.

30 Rodgers KG, Manifold C. 360-degree feedback: possibilities for assessment of the ACGME core competencies for emergency medicine residents. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2002;9:1300-1304.

31 Swing SR, Schneider S, Bizovi K, et al. Using patient care quality measures to assess educational outcomes. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2007;14(5):463-473.

32 Sherbino J, Frank J, Lee C, et al. Evaluating “ED STAT!”: a novel and effective faculty development program to improve emergency department teaching. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2006;13:1062-1069.

33 Faculty Development Handbook. Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Online. Available: www.saem.org (accessed 20 August 2007)

34 Graham IS, Gleason AJ, Keogh GW, et al. Australian curriculum framework for junior doctors. Medical Journal of Australia. 2007;186(7):S14-S19.

35 Davis D, Thomson M, O’Brien M, et al. Do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:867-874.