Chest Tube Placement (Assist)

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• The thoracic cavity, in normal conditions, is a closed airspace. Any disruption results in the loss of negative pressure within the intrapleural space. Air or fluid that enters the space competes with the lung, resulting in collapse of the lung. Associated conditions are the result of disease, injury, surgery, or iatrogenic causes.

• Chest tubes are sterile flexible vinyl or silicone nonthrombogenic catheters approximately 20 inches (51 cm) long, varying in size from 12F to 40F. The size of the tube placed is determined by the condition. Chest tubes inserted for traumatic hemopneumothorax or hemothorax (blood) should be large (36F to 40F). Medium tubes (24F to 36F) should be used for fluid accumulation (pleural effusions). Tubes inserted for pneumothorax (air) should be small (12F to 24F).2

• Indications for chest tube insertion include the following:

Pneumothorax (collection of air in the pleural space)

Pneumothorax (collection of air in the pleural space)

Hemothorax (collection of blood)

Hemothorax (collection of blood)

Hemopneumothorax (accumulation of air and blood in the pleural space)

Hemopneumothorax (accumulation of air and blood in the pleural space)

Thoracotomy (e.g., open heart surgery, pneumonectomy)

Thoracotomy (e.g., open heart surgery, pneumonectomy)

Pyothorax or empyema (collection of pus)

Pyothorax or empyema (collection of pus)

Chylothorax (collection of chyle from the thoracic duct)

Chylothorax (collection of chyle from the thoracic duct)

Cholothorax (collection of fluid containing bile)

Cholothorax (collection of fluid containing bile)

• A pneumothorax may be classified as an open, closed, or tension pneumothorax.

Open pneumothorax: The chest wall and the pleural space are penetrated, which allows air to enter the pleural space, as in a penetrating injury or trauma; a surgical incision in the thoracic cavity (i.e., thoracotomy); or a complication of surgical treatment (e.g., unintentional puncture during invasive procedures, such as thoracentesis or central venous catheter insertion).

Open pneumothorax: The chest wall and the pleural space are penetrated, which allows air to enter the pleural space, as in a penetrating injury or trauma; a surgical incision in the thoracic cavity (i.e., thoracotomy); or a complication of surgical treatment (e.g., unintentional puncture during invasive procedures, such as thoracentesis or central venous catheter insertion).

Closed pneumothorax: The pleural space is penetrated, but the chest wall is intact, which allows air to enter the pleural space from within the lung, as in spontaneous pneumothorax. A closed pneumothorax occurs without apparent injury and often is seen in individuals with chronic lung disorders (e.g., emphysema, cystic fibrosis, tuberculosis, necrotizing pneumonia) and in young tall men who have a greater than normal height-to-width chest ratio; after blunt traumatic injury; or iatrogenically, occurring as a complication of medical treatment (e.g., intermittent positive-pressure breathing [IPPB], mechanical ventilation with positive end-expiratory pressure [PEEP]).

Closed pneumothorax: The pleural space is penetrated, but the chest wall is intact, which allows air to enter the pleural space from within the lung, as in spontaneous pneumothorax. A closed pneumothorax occurs without apparent injury and often is seen in individuals with chronic lung disorders (e.g., emphysema, cystic fibrosis, tuberculosis, necrotizing pneumonia) and in young tall men who have a greater than normal height-to-width chest ratio; after blunt traumatic injury; or iatrogenically, occurring as a complication of medical treatment (e.g., intermittent positive-pressure breathing [IPPB], mechanical ventilation with positive end-expiratory pressure [PEEP]).

Tension pneumothorax: Air leaks into the pleural space through a tear in the lung and has no means to escape from the pleural cavity, creating a one-way valve effect. With each breath the patient takes, air accumulates, pressure within the pleural space increases, and the lung collapses. This condition causes the mediastinal structures (i.e., heart, great vessels, and trachea) to be compressed and shift to the opposite or unaffected side of the chest. Venous return and cardiac output are impeded, and collapse of the unaffected lung is possible. This life-threatening emergency requires prompt recognition and intervention.

Tension pneumothorax: Air leaks into the pleural space through a tear in the lung and has no means to escape from the pleural cavity, creating a one-way valve effect. With each breath the patient takes, air accumulates, pressure within the pleural space increases, and the lung collapses. This condition causes the mediastinal structures (i.e., heart, great vessels, and trachea) to be compressed and shift to the opposite or unaffected side of the chest. Venous return and cardiac output are impeded, and collapse of the unaffected lung is possible. This life-threatening emergency requires prompt recognition and intervention.

Special applications: Chest tubes can be used to instill anesthetic solutions and sclerosing agents.

Special applications: Chest tubes can be used to instill anesthetic solutions and sclerosing agents.

• Lung that is densely adherent to the chest wall throughout the hemithorax is an absolute contraindication to chest tube therapy.

• Use of chest tubes in patients with multiple adhesions, giant blebs, or coagulopathies is carefully considered; however, these relative contraindications are superseded by the need to reexpand the lung. When possible, any coagulopathy or platelet defect should be corrected before chest tube insertion. The differential diagnosis between a pneumothorax and bullous disease necessitates careful radiologic assessment.4

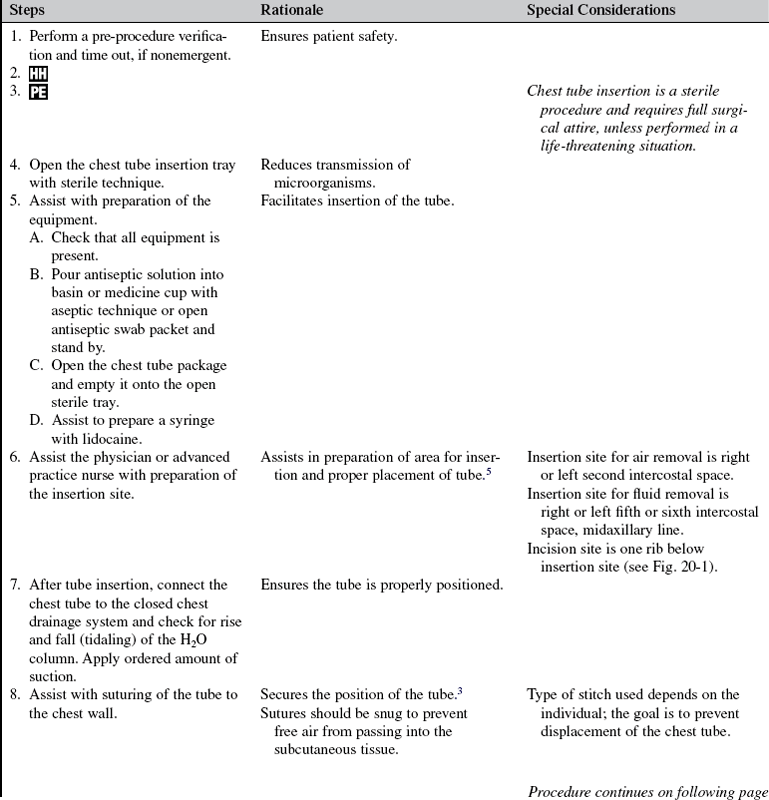

• The tube size and insertion site selected for the chest tube are determined by the indication.4 If draining air, the tube is placed near the apex of the lung (second intercostal space); if draining fluid, the tube is placed near the base of the lung (fifth or sixth intercostal space; see Fig. 20-1).

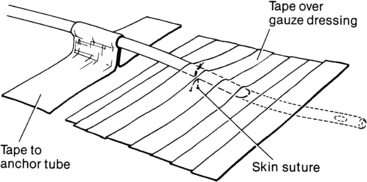

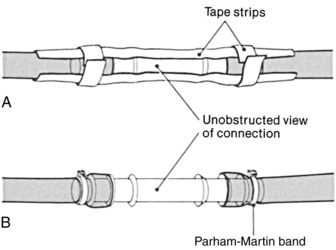

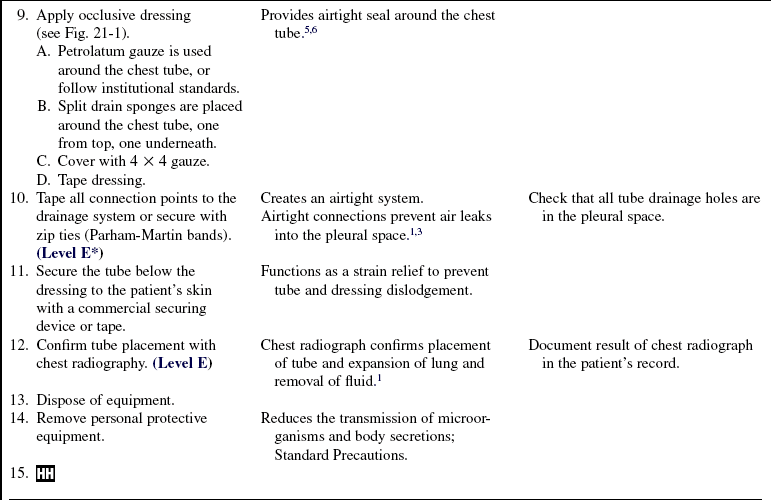

• When the tube is in place, the tube is sutured to the skin to prevent displacement, and an occlusive dressing is applied (Fig. 21-1). The chest tube also is connected to a chest drainage system (see Procedure 24) to remove air and fluid from the pleural space, which facilitates reexpansion of the collapsed lung. All connection points are secured with tape or zip ties (Parham-Martin bands) to ensure that the system remains airtight (Fig. 21-2).

• The water-seal chamber should bubble gently immediately on insertion of the chest tube during expiration and with coughing. Continuous bubbling in this chamber indicates a leak within the patient or in the chest drainage system. Fluctuations in the water level in the water-seal chamber of 5 to 10 cm, rising during inhalation and falling during expiration, should be observed with spontaneous respirations. If the patient is on mechanical ventilation, the pattern of fluctuation is just the opposite. Any suction applied must be disconnected temporarily to assess correctly for fluctuations in the water-seal chamber.

• Mediastinal tubes generally are placed in the operating room by a surgeon after cardiac surgery.

EQUIPMENT

• Antiseptic solution or antiseptic swab packets

• Caps, masks, sterile gloves, gowns, drapes

• Protective eyewear (goggles)

• Local anesthetic: 1% lidocaine solution (without epinephrine)

Sterile towels, 4 × 4 sterile gauze

Sterile towels, 4 × 4 sterile gauze

Two Kelly clamps, curved clamps

Two Kelly clamps, curved clamps

Monofilament or silk suture material with cutting needle

Monofilament or silk suture material with cutting needle

• Thoracotomy tubes (12F to 40F, as appropriate)

• Closed chest drainage system

• Suction connector and connecting tubing (usually 6 feet for each tube)

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the procedure (if patient condition and circumstances allow) and the reason for the chest tube insertion.  Rationale: This communication identifies patient and family knowledge deficits concerning the patient’s condition, expected benefits, and potential risks and allows time for questions to clarify information and to voice concerns. Explanations decrease patient anxiety and enhance cooperation.

Rationale: This communication identifies patient and family knowledge deficits concerning the patient’s condition, expected benefits, and potential risks and allows time for questions to clarify information and to voice concerns. Explanations decrease patient anxiety and enhance cooperation.

• Explain that the patient’s participation during the procedure is to remain as immobile as possible and do relaxed breathing.  Rationale: This explanation facilitates insertion of the chest tube and prevents complications during insertion.

Rationale: This explanation facilitates insertion of the chest tube and prevents complications during insertion.

• After the procedure, instruct the patient to sit in a semi-Fowler’s position (unless contraindicated).  Rationale: This position facilitates drainage from the lung by allowing air to rise and fluid to settle to be removed via the chest tube. This position also makes breathing easier.

Rationale: This position facilitates drainage from the lung by allowing air to rise and fluid to settle to be removed via the chest tube. This position also makes breathing easier.

• Instruct the patient to turn and change position every 2 hours. The patient may lie on the side with the chest tube but should keep the tubing free of kinks.  Rationale: Turning and changing position prevent complications related to immobility and retained pulmonary secretions. Keeping the tube free of kinks maintains patency of the tube, facilitates drainage, and prevents the accumulation of pressure within the pleural space that interferes with lung reexpansion.

Rationale: Turning and changing position prevent complications related to immobility and retained pulmonary secretions. Keeping the tube free of kinks maintains patency of the tube, facilitates drainage, and prevents the accumulation of pressure within the pleural space that interferes with lung reexpansion.

• Instruct the patient to cough and deep breathe, with splinting of the affected side.  Rationale: Coughing and deep breathing increase pressure within the pleural space, facilitating drainage, promoting lung reexpansion, and preventing respiratory complications associated with retained secretions. The application of firm pressure over the chest tube insertion site (i.e., splinting) decreases pain and discomfort.

Rationale: Coughing and deep breathing increase pressure within the pleural space, facilitating drainage, promoting lung reexpansion, and preventing respiratory complications associated with retained secretions. The application of firm pressure over the chest tube insertion site (i.e., splinting) decreases pain and discomfort.

• Encourage active or passive range-of-motion exercises of the arm on the affected side.  Rationale: The patient may limit movement of the arm on the affected side to decrease the discomfort at the insertion site, which results in joint discomfort and potential joint contractures.

Rationale: The patient may limit movement of the arm on the affected side to decrease the discomfort at the insertion site, which results in joint discomfort and potential joint contractures.

• Instruct the patient and family about activity as prescribed while maintaining the drainage system below the level of the chest.  Rationale: This activity facilitates gravity drainage and prevents backflow and potential infectious contamination into the pleural space.

Rationale: This activity facilitates gravity drainage and prevents backflow and potential infectious contamination into the pleural space.

• Instruct the patient about the availability of prescribed analgesic medication and other pain relief strategies.  Rationale: Pain relief ensures comfort and facilitates coughing, deep breathing, positioning, range of motion, and recuperation.

Rationale: Pain relief ensures comfort and facilitates coughing, deep breathing, positioning, range of motion, and recuperation.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Assess significant medical history or injury, including chronic lung disease, spontaneous pneumothorax, hemothorax, pulmonary disease, therapeutic procedures, and mechanism of injury.  Rationale: Medical history or injury may provide the etiologic basis for the occurrence of pneumothorax, empyema, pleural effusion, or chylothorax.

Rationale: Medical history or injury may provide the etiologic basis for the occurrence of pneumothorax, empyema, pleural effusion, or chylothorax.

• Evaluate diagnostic test results (if patient’s condition does not necessitate immediate intervention), including chest radiograph and arterial blood gases.  Rationale: Diagnostic testing confirms the presence of air or fluid in the pleural space, a collapsed lung, hypoxemia, and respiratory compromise.

Rationale: Diagnostic testing confirms the presence of air or fluid in the pleural space, a collapsed lung, hypoxemia, and respiratory compromise.

• Perform hand hygiene.  Rationale: Reduces the transmission of microorganisms and body secretions (Standard Precautions).

Rationale: Reduces the transmission of microorganisms and body secretions (Standard Precautions).

• Assess baseline cardiopulmonary status for signs and symptoms that necessitate chest tube insertion8:

Decreased or absent breath sounds on affected side

Decreased or absent breath sounds on affected side

Crackles adjacent to the affected area

Crackles adjacent to the affected area

Asymmetrical chest excursion with respirations

Asymmetrical chest excursion with respirations

Hyperresonance in the affected side (pneumothorax)

Hyperresonance in the affected side (pneumothorax)

Subcutaneous emphysema (pneumothorax)

Subcutaneous emphysema (pneumothorax)

Dullness or flatness in the affected side (hemothorax, pleural effusion, empyema, chylothorax)

Dullness or flatness in the affected side (hemothorax, pleural effusion, empyema, chylothorax)

Anxiety, restlessness, apprehension

Anxiety, restlessness, apprehension

Tracheal deviation to the unaffected side (tension pneumothorax)

Tracheal deviation to the unaffected side (tension pneumothorax)

Rationale: Accurate assessment of signs and symptoms allows for prompt recognition and treatment. Baseline assessment provides comparison data for evaluation of changes and outcomes of treatment.

Rationale: Accurate assessment of signs and symptoms allows for prompt recognition and treatment. Baseline assessment provides comparison data for evaluation of changes and outcomes of treatment.

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that the patient understands preprocedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: This communication evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

Rationale: This communication evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

• Obtain consent if circumstances allow.  Rationale: Invasive procedures, unless performed with implied consent in a life-threatening situation, require written consent of the patient or significant other.

Rationale: Invasive procedures, unless performed with implied consent in a life-threatening situation, require written consent of the patient or significant other.

• Insure that the practitioner inserting the chest tube has identified the insertion site and marked the skin with an indelible marker.  Rationale: The insertion site is identified by the practitioner inserting the chest tube, who marks it with an indelible marker, and determined by the indication for the chest tube. For air, the second intercostal space is used; for fluid, the fifth or sixth intercostal space is used.

Rationale: The insertion site is identified by the practitioner inserting the chest tube, who marks it with an indelible marker, and determined by the indication for the chest tube. For air, the second intercostal space is used; for fluid, the fifth or sixth intercostal space is used.

• Consult with the practitioner for the appropriate size chest tube to be inserted.  Rationale: Evacuation of air necessitates a smaller tube; evacuation of fluid necessitates larger tubes.

Rationale: Evacuation of air necessitates a smaller tube; evacuation of fluid necessitates larger tubes.

• Assist the patient to the lateral, supine (for pneumothorax), or semi-Fowler’s position (for hemothorax).6  Rationale: This positioning enhances accessibility to the insertion site for positioning of the chest tube.

Rationale: This positioning enhances accessibility to the insertion site for positioning of the chest tube.

• Administer prescribed analgesics or sedatives as needed; follow institutional policy for moderate or procedural sedation.  Rationale: Analgesics and sedatives reduce the discomfort and anxiety experienced and facilitate patient cooperation.

Rationale: Analgesics and sedatives reduce the discomfort and anxiety experienced and facilitate patient cooperation.

• Administer oxygen and monitor pulse oximeter or end-tidal carbon dioxide level.  Rationale: Real-time assessment of patient’s respiratory status during the procedure is provided.

Rationale: Real-time assessment of patient’s respiratory status during the procedure is provided.

• Ensure patient has a patent intravenous (IV) access.  Rationale: This access provides a route for analgesic, sedation, and emergency medications.

Rationale: This access provides a route for analgesic, sedation, and emergency medications.

References

![]() 1. Buchman, TG, Hall, BL, Bowling, WM, et al, Thoracic traumaTininalli JE, Kelen DG, Stapczynski JS, eds.. Emergency medicine. a comprehensive guide. ed 6. McGraw-Hill, New York, 2004:1595–1612.

1. Buchman, TG, Hall, BL, Bowling, WM, et al, Thoracic traumaTininalli JE, Kelen DG, Stapczynski JS, eds.. Emergency medicine. a comprehensive guide. ed 6. McGraw-Hill, New York, 2004:1595–1612.

2. Dev, SP, Nascimiento, B, Simone, C, et al. Chest-tube -insertion. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357:e15.

3. Irwin, RS, Rippe, JM. Intensive care medicine,. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott and -Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

![]() 4. Laws, D, Neville, E, Duffy, J. BTS guidelines for insertion of a chest drain. Thorax. 2003; 58(Suppl II):ii53–ii59.

4. Laws, D, Neville, E, Duffy, J. BTS guidelines for insertion of a chest drain. Thorax. 2003; 58(Suppl II):ii53–ii59.

5. May, G, Bartram, T. The use of intrapleural anaesthetic to reduce the pain of chest drain insertion. Emerg Med J. 2007; 24:300–301.

![]() 6. Roberts, JR. Clinical procedures in emergency medicine, ed 4. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004.

6. Roberts, JR. Clinical procedures in emergency medicine, ed 4. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004.

7. Sullivan, B. Nursing management of patients with a chest drain. Br J Nurs. 2008; 17(6):388–393.

![]() 8. Thompson, JM, McFarland, GK, Hirsh, JE, et al. Mosby’s clinical nursing, ed 5. St Louis: Mosby; 2002.

8. Thompson, JM, McFarland, GK, Hirsh, JE, et al. Mosby’s clinical nursing, ed 5. St Louis: Mosby; 2002.

Argall, J. Seldinger technique chest drains and complication rate. Emerg Med J. 2003; 20:169–170.

Charnock, Y, Evans, D, Nursing management of chest drains. a systematic review. Aust Crit Care 2001; 14:156–160.

Coughlin, AM, Parchinsky, C. Go with the flow of chest tube therapy. Nursing. 2006; 36:36–42.

Ellis, H. The applied anatomy of chest drain insertion. Br J Hosp Med (London). 2007; 68:M44–45.

Frankel, TL, Hill, PC, Stamou, SC, et al. Silastic drains vs conventional chest tubes after coronary artery bypass. Chest. 2003; 124:108–113.

Gareeboo, S, Singh, S, Tube thoracostomy. how to insert a chest drain. Br J Hosp Med (London) 2006; 67:M16–18.

Lehwaldt, D, Timmins, F, Nurses’ knowledge of chest drain care. an exploratory descriptive survey. Nurs Crit Care 2005; 10:192–200.

Zgoda, MA, Lunn, W, Ashiku, S, et al, Minimally invasive techniques. direct visual guidance for chest tube placement through a single-port thoracoscopya novel technique. Chest 2005; 127:1805–1807.