Psychiatric Emergencies

Edited by George Jelinek

20.1 Mental state assessment

George Jelinek and Sylvia Andrew-Starkey

Epidemiology

Mental health disorders are one of the three leading causes of total burden of disease and injury in Australia, alongside cancer and cardiovascular disease [1–3]. In middle age, it is the leading cause of non-fatal disease burden in the Australian population. There is no doubt that mental health disorders have a high prevalence, are disabling and are high cost in both human and socioeconomic terms [1,2].

In terms of disability, it has been estimated that having moderate to severe depression is the equivalent of having congestive cardiac failure [3], chronic severe asthma or chronic hepatitis B [2]. Severe post-traumatic stress syndrome was comparable to the disability from paraplegia and severe schizophrenia was comparable to quadriplegia, in terms of disability [2]. Over the 10 years to 2007, emergency department (ED) presentations rose 8% in the USA, whereas mental health presentations for the same time period rose 38%, contributing significantly to ED overcrowding [4]. This trend has been mirrored in Australia.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare report into Mental Health Services in 2012 estimated that there were nearly a quarter of a million occasions of service to Australian EDs in 2009/10 where the primary problem was thought to be due to a mental health disorder, with an average annual increase of 3.6% between 2005–06 and 2009–10 [1]. A little over 3% of Australian public hospital ED presentations are for mental health related problems, correlating well with other studies and US figures, which estimate 2–6% of emergency medicine presentations are primarily due to mental health disorders [4–7].

Two-thirds of these people are between the ages of 15 and 44 years (compared to 42% for the general population presenting to a suburban ED); 29% have anxiety and neurotic disorders, 21% mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance abuse, 19% mood disorders and 17% schizophrenia or delusional disorders [4].

This is a significant underestimate of the prevalence of mental health disease in the ED as many patients remain undiagnosed and many have active medical conditions and a mental health diagnosis may be secondary [6].

It is estimated that 17.7% of adult Australians admitted to hospital report a mental health issue in the previous 12 months. An estimated 0.4–0.7% of the adult population suffer from a psychotic episode in any 1 year [2]. Mental health issues are highly prevalent and relevant.

Introduction to the mental state examination

The mainstreaming of mental health patients into general EDs has brought problems and anxieties for staff. Staff often feel a lack of confidence because they are dealing with a population of patients unfamiliar to them. They can also feel inadequate due to poor assessment skills [7,8].

Recent Australian studies have shown ED clinicians are most concerned about knowledge gaps in risk assessment, particularly related to self-harm, violence and aggression, and distinguishing psychiatric from physical illness [9]. ED clinicians routinely report the need for more education on mental health related presentations [10]. A high proportion of mental health patients have drug and alcohol intoxication. This confounds the evaluation and treatment, lengthens the stay of these patients within the ED and delays their disposition.

Mental health patients can be assigned lower triage categories and longer waits to be seen by staff than mainstream patients and there is more variation in triage categorization for mental health patients [11]. They have a higher chance of leaving before assessment has begun or is complete and the overall increase in length of assessment time has the potential to increase violence in the ED [7,8].

With this in mind, there has been much work over the last 10 years on the assessment of mental health patients in a general ED.

Bias and discrimination

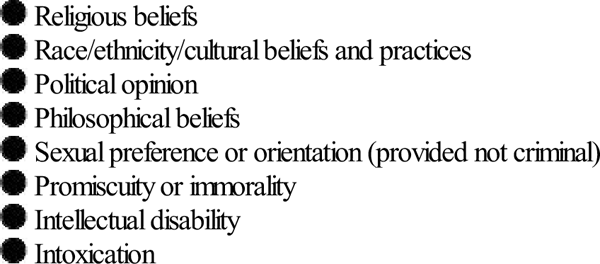

It is important for health professionals assessing the mentally ill to be aware of their own potential biases. An interviewer’s past history and personal beliefs can influence a mental state assessment and the interviewer should be aware of this. These beliefs may stem from past personal or professional experience (Table 20.1.1).

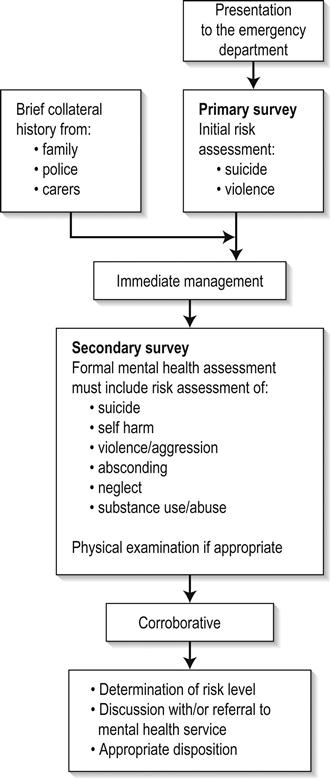

ABC of the MSE

A mental state examination (MSE) is analogous to the management of severe trauma. There is an initial risk assessment looking for immediately life-threatening risks to the patient or staff. The triage nurse and the treating doctor should then obtain a brief collateral history from the emergency services or carers and initial management is based on this assessment. Regardless of threat, all assessments should balance the safety of both patient and staff with privacy and dignity [7].

Assessment should be based on [12]:

If the situation is relatively controlled, the formal mental health assessment should then take place. Further information is gathered from the community. A provisional assessment and management plan is developed in conjunction with the mental health team and appropriate disposition is arranged (Fig. 20.1.1).

Triage

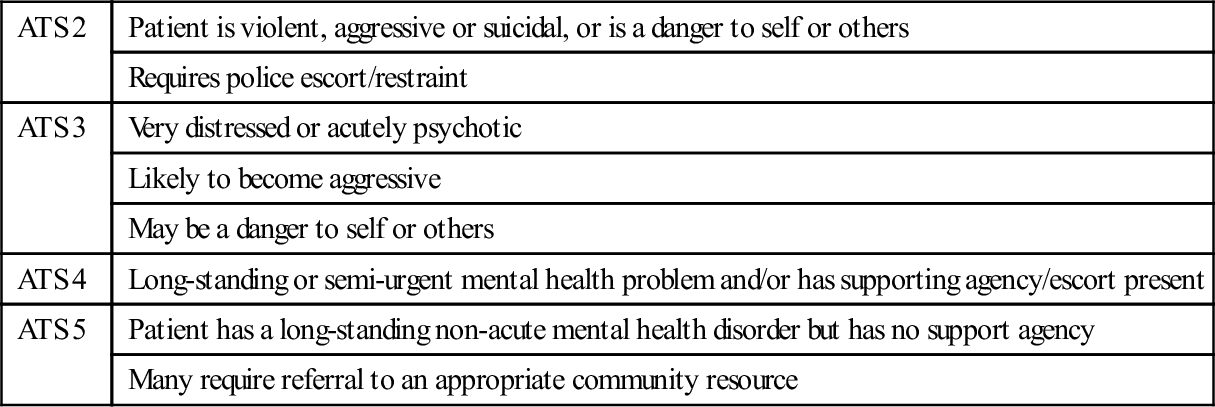

The Mental Health Triage Scale (Table 20.1.2) has been developed and modified to be included into the Australian Triage Scale (ATS) [7,13,14]. It is very broad and asks the triage nurse to make four assessments: risk of suicide/self-harm, risk of aggression/harm to others, risk of absconding and whether the patient is intoxicated. From this, the triage nurse determines the ATS and urgency of initial treatment. It is also helpful to determine if the patient is known to a mental health service.

Table 20.1.2

The mental health triage scale

| ATS 2 | Patient is violent, aggressive or suicidal, or is a danger to self or others |

| Requires police escort/restraint | |

| ATS 3 | Very distressed or acutely psychotic |

| Likely to become aggressive | |

| May be a danger to self or others | |

| ATS 4 | Long-standing or semi-urgent mental health problem and/or has supporting agency/escort present |

| ATS 5 | Patient has a long-standing non-acute mental health disorder but has no support agency |

| Many require referral to an appropriate community resource |

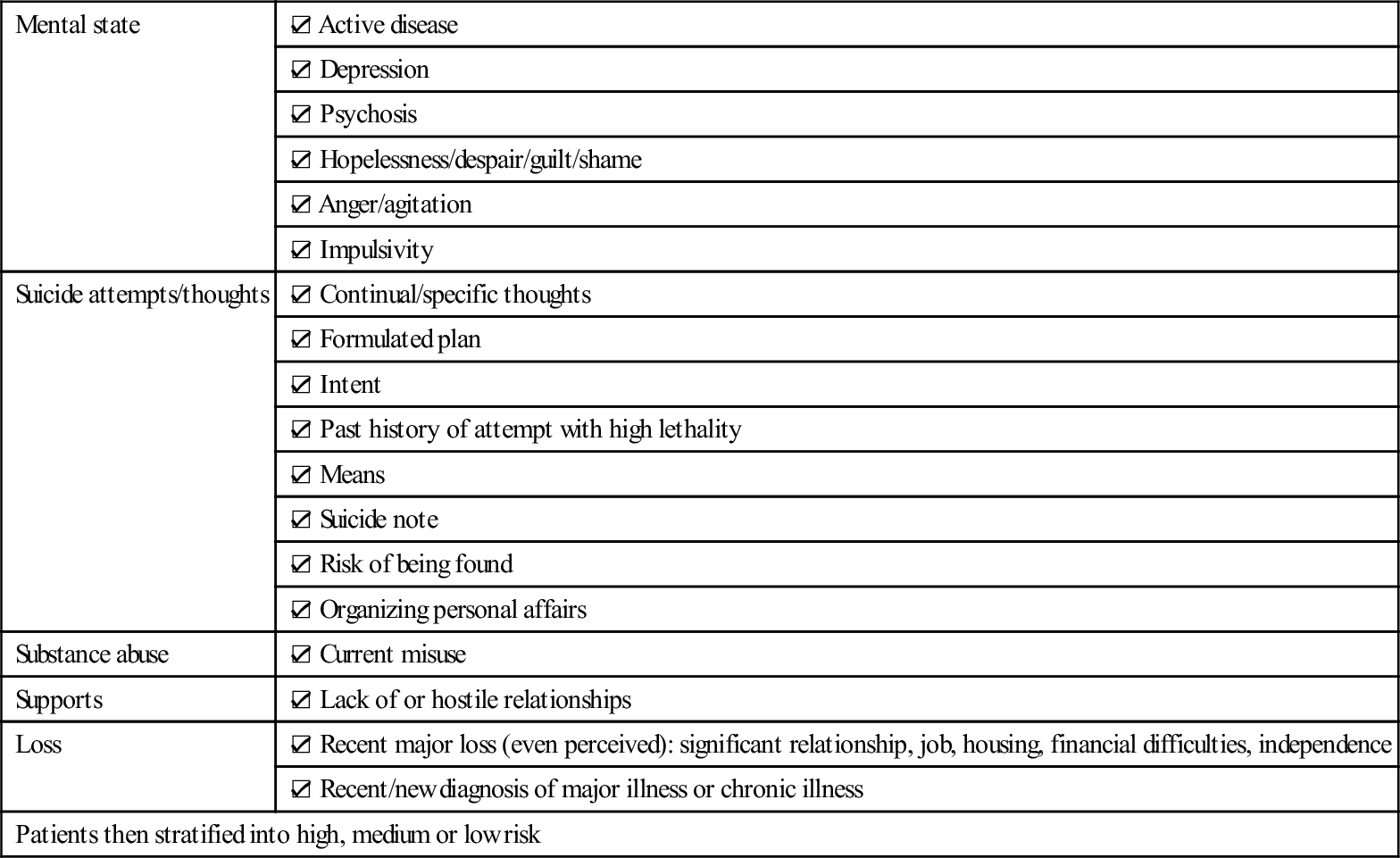

Many centres have developed a triage risk assessment proforma. For ease of use, many of these have included ‘tick box’ areas. A compilation of multiple assessment tools used throughout Australia is shown in Tables 20.1.3–20.1.5[2,5,12–15].

Table 20.1.3

Brief screening suicide risk template

| Mental state | ☑ Active disease |

| ☑ Depression | |

| ☑ Psychosis | |

| ☑ Hopelessness/despair/guilt/shame | |

| ☑ Anger/agitation | |

| ☑ Impulsivity | |

| Suicide attempts/thoughts | ☑ Continual/specific thoughts |

| ☑ Formulated plan | |

| ☑ Intent | |

| ☑ Past history of attempt with high lethality | |

| ☑ Means | |

| ☑ Suicide note | |

| ☑ Risk of being found | |

| ☑ Organizing personal affairs | |

| Substance abuse | ☑ Current misuse |

| Supports | ☑ Lack of or hostile relationships |

| Loss | ☑ Recent major loss (even perceived): significant relationship, job, housing, financial difficulties, independence |

| ☑ Recent/new diagnosis of major illness or chronic illness | |

| Patients then stratified into high, medium or low risk | |

Table 20.1.4

☑ Alert on chart

☑ Previous history of violence/threatening behaviour: verbal or physical

☑ Aggressive behaviour/thoughts

☑ Homicidal ideation

☑ Use of weapons previously

☑ Access to weapons

☑ Intoxicated

☑ Middle-aged male

Patients then stratified into high, medium or low risk

Table 20.1.5

Mode of arrival

☑ Police

☑ Handcuffed

☑ Family/carer coercion

☑ Voluntary

☑ Past history of absconding behaviour

☑ Alert on chart

☑ Verbalizing intent to leave

☑ Lack of insight into illness

☑ Poor/non-compliance with medication

Patients then stratified into high, medium or low risk

It is recommended that any patient who scores ‘high risk’ in any one area or ‘medium risk’ in two areas is treated as a ‘high-risk’ patient. Ensuing management of ‘high-risk’ patients depends on: local protocols, levels and presence of security, police intervention, restraint and sedation guidelines and guidelines for the urgent assessment by ED and/or by mental health services.

Aims of mental health assessment

The aims of the formal mental health assessment are to determine the following:

Does the patient have a mental illness?

Does the patient have a mental illness?

Is there a question of safety for the patient or for others?

Is there a question of safety for the patient or for others?

Does the patient have insight into the illness?

Does the patient have insight into the illness?

Will the patient comply with suggested treatment?

Will the patient comply with suggested treatment?

Can the patient be managed in the community or is hospitalization required?

Can the patient be managed in the community or is hospitalization required?

Only if all of the above are answered, can management and appropriate disposition be considered.

The formal psychiatric interview

Introduction

The environment in which the mental state assessment is conducted is important. Behaviourally disturbed people tolerate noise poorly and have short concentration spans. The interview room should be quiet, private, make the patient feel safe and the interviewer should avoid all interruptions. These prerequisites are increasingly difficult to attain in current access-blocked environments.

The interviewer should sit at the same level as the patient and impart empathy. The voice should be quiet and calming. The interviewer should use non-judgemental language and open-ended questions [13,16]. It is important that the interviewer also feels safe and secure. If any risk is felt, the interviewer should have security or police present in the room or just outside. Depending on state legislation and hospital policy, the interviewer may request to have the patient searched. The interviewer should also note the nearest duress alarm and may choose to wear a personal alarm. The interviewer should sit within easy access of an exit and should never be boxed into a corner. If an interviewer begins to feel uncomfortable, there is always the option of leaving and returning to complete the assessment at a later stage. All threats, attempts and gestures suggestive of violence should be treated seriously.

First part of the interview: direct questioning

Basic demographic information

The formal interview has become less diagnosis focused and more problem based. Management is centred around the alleviation of symptoms and return to function. Thus, the psychiatric interview has become somewhat less structured.

It is wise to establish rapport with the patient by personal introduction and explaining the purpose of the interview. The interviewer can begin by asking a series of non-threatening questions, such as demographics. This information is often required as many mental health services rely on an appropriate post code to determine follow-up management.

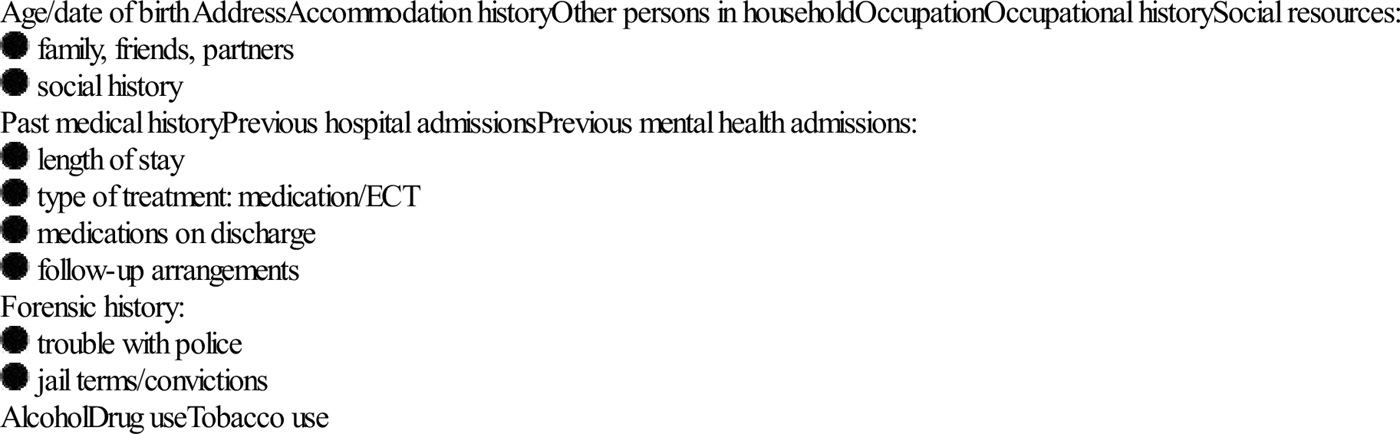

These questions assist by building a profile of lifestyle, relationships and thought processes. Likelihood of success or failure of particular treatment modalities may be assisted by knowledge of previous hospital admissions, both general hospital and mental health (Table 20.1.6).

Table 20.1.6

Demographic information required

The process of obtaining a mental health assessment is different to that of a general medical assessment. In a general medical history, a series of questions is asked and the response is written. In a mental health assessment, responses are also interpreted. The interviewer is asked to form an opinion as to how thoughts are processed, based on observations. The interviewer is asked to interpret the patient’s thought patterns by what, and how, the patient tells the interviewer.

Presenting complaint

The patient is asked to recall the sequence of events prior to presentation to the ED. The interviewer should explore the circumstances of the behaviour, reasons for it, degree of planning or impulsivity and its context. Were drugs and alcohol involved? Was there a recent precipitating event? It is often useful to get the patient to recall the previous 48–72 hours leading up to the event.

This usually leads to questioning regarding current difficulties. The interviewer should explore the nature of current problems. They may be financial or legal problems, isolation, bereavement, impending or actual loss, or diagnosis of major illness. Have there been any recent changes and who are their usual support people? An exploration of significant relationships is important along with the depth and duration of these relationships. It is useful to explore the patient’s usual coping methods when under stress.

Mood and affect

There should be formal questioning regarding the patient’s mood (internal feelings) and whether it is in keeping with affect (external expression). The mood may be incongruent with affect, swing wildly between extremes (labile) or be inappropriate.

Usually mood is assessed by asking about the patient’s ability to cope with activities of daily living, such as eating, weight loss or gain, sleep disturbance (early morning wakening or trouble getting to sleep) and general hygiene. The patient’s ability to concentrate may also diminish with increasing mood disturbance, reflected by the ability to perform normal work duties.

This may lead to direct questioning regarding mood and thoughts of suicide. It is important to be direct in asking the patient about suicide and whether there is a formulated plan. A well thought out plan with clear means of carrying out threats is of great concern.

Delusions and hallucinations

Delusions and hallucinations are often personal and the patient may not want to disclose intimate thoughts and beliefs to the interviewer. Hallucinations may be auditory, visual, tactile, olfactory, somatic or gustatory. The context in which they occur should be explored. Hypnagogic (occurring just before sleep) and hypnopompic (occurring on wakening) hallucinations are more benign than others. Common themes for all types of hallucinations include suicide, persecution, religion, control, reference, grandeur or somatization.

Insight and judgement

Insight is the degree of understanding of what is happening and why. This may be:

awareness of being sick and needing help but denying it at the same time

awareness of being sick and needing help but denying it at the same time

awareness of being sick but blaming it on external factors

awareness of being sick but blaming it on external factors

awareness that illness is due to something unknown within the patient

awareness that illness is due to something unknown within the patient

It is important to determine the patient’s level of insight. This determines appropriate treatment and management, level of supervision required and the likelihood of compliance with treatment.

Second part of interview: observation

Key elements

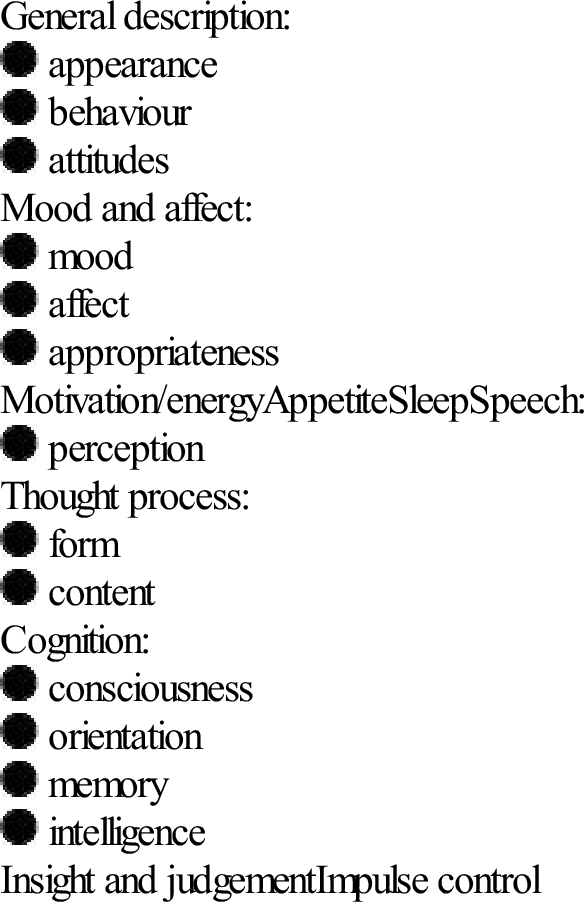

The second part of the MSE can be more difficult to conceptualize. It relies on the interviewer actively observing the patient’s behaviour and conversation and interpreting thoughts. A summary is given in Table 20.1.7.

Table 20.1.7

Overview of mental state examination

| General description: |

| Mood and affect: |

| Motivation/energy |

| Appetite |

| Sleep |

| Speech: |

| Thought process: |

| Cognition: |

| Insight and judgement |

| Impulse control |

This part of the interview can be difficult to remember and different services have developed a multitude of acronyms for remembering the various elements of the remaining mental health assessment. Listed below are two.

ABC of Mental Health Assessment [12]:

GFCMA – ‘Got Four Clients on Monday Afternoon’ [13]:

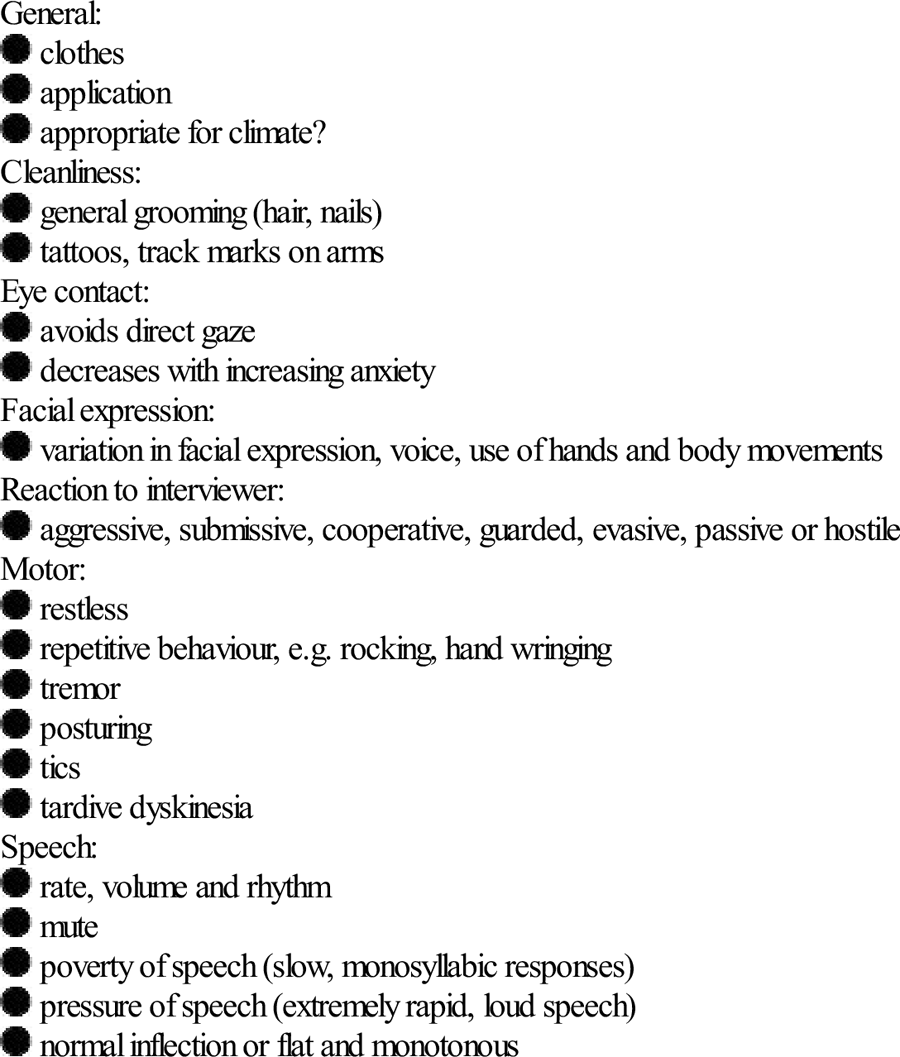

Appearance, attitude and behaviour

This determines the patient’s ability to self-care. Table 20.1.8 lists features that may require particular attention. Attitude is important as it may indicate whether a patient is compliant with management and treatment. Abnormal posturing or repetitive behaviours should be noted. These may indicate increasing thought disturbance. With increasing aggression and agitation, there may be motor restlessness, pacing and hand wringing. Tension may escalate rapidly and steps should be taken early to diffuse the situation.

Table 20.1.8

Appearance, attitude and behaviour

The interviewer should note the rate, volume and rhythmicity of speech. This can range from completely mute, through monosyllabic answers, to rapid, loud speech indicative of pressure of speech. The tone, inflection, content and structure of speech should be noted. The interviewer should determine if the speech is fluent, if the thoughts behind it are logical and whether it flows appropriately for the situation.

Thought disorder

This is speech that does not reach its goal, is not fluent and is interrupted often with many pauses or changes in direction. A list with explanations is given in Table 20.1.9.

Table 20.1.9

| Circumstantiality | Delays in reaching goals by long-winded explanations, but eventually gets there |

| Distractible speech | Changes topic according to what is happening around the patient |

| Loosening of associations | Logical thought progression does not occur and ideas shift from one subject to another with little or no association between them |

| Flight of ideas | Fragmented, rapid thoughts that the patient cannot express fully as they are occurring at such a rapid rate |

| Tangentiality | Responses that superficially appear appropriate, but which are completely irrelevant or oblique |

| Clanging | Speech where words are chosen because they rhyme and do not make sense |

| Neologisms | Creation of new words with no meaning except to the patient |

| Thought blocking | Interruption to thought process where thoughts are absent for a few seconds and are unable to be retrieved |

Thought content

There are often recurrent themes in the speech of an acutely disturbed patient. These may revolve around suicide, persecution, control, reference, religion or somaticism (the extremes of which are nihilistic delusions – the belief that part of the self does not exist, is dead or decaying) or they may be grandiose in nature.

Perception

A patient may be actively hallucinating despite denying this on questioning. It is important to note if the patient’s eyes suddenly switch direction for no apparent reason or they appear to be listening to a voice. These movements are often quite subtle and easily missed if observation is not active.

Cognitive assessment and physical examination

A formal examination of cognitive function and a thorough physical examination complete the full psychiatric assessment. The interviewer should ensure that the patient does not have an acute confusional state secondary to a physical condition that may account for a behavioural problem.

A number of tools are available to assess cognitive functioning. These comprise assessments in orientation, concentration, memory, language, abstraction and judgement. An assessment of a patient’s cognitive functioning and intelligence may assist in deciding the best way to deal with problems.

Approximately 20% of mental health patients have a concurrent active medical disorder requiring treatment and possibly contributing to the acute behavioural disturbance [6]. Investigations depend on physical findings but may include creatine kinase, urine drug screen, electroencephalogram, computed tomography and lumbar puncture. Only after this can an emergency medicine practitioner plan the most appropriate management.

Conclusion

Although time consuming, a good mental health assessment is vital for the appropriate management and disposition of what is an increasingly large group of patients in the ED. If able to formulate an opinion on the risk assessments regarding suicide, violence and flight risk and the aims of the MSE, the emergency clinician will be able to present to mental health services a comprehensive picture of the patient.

The mental health professional is then able to administer mental health first aid [2], the principles of which are:

20.2 Distinguishing medical from psychiatric causes of mental disorder presentations

David Spain

Introduction

Emergency physicians often assess patients who have suspected mental disorder. The critical question posed is: what is the cause of this? Causes are many but broadly include psychiatric, medical, intoxication and behavioural. Identifying the likely cause and careful consideration of the capability of local facilities usually leads to correct disposition, reducing medical costs and morbidity [1]. In practice, emergency physicians need a simple classification defining the principal diagnosis of the presenting mental disorder consistent with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) terminology. This allows us to communicate with psychiatric colleagues and should assist diagnostic, management and disposition accuracy. Table 20.2.1 is such a suggested classification.

Table 20.2.1

A simple classification of principal diagnosis of mental disorder for emergency physicians

| DSM-IV terminology | Broad traditional clinical grouping | Likely principal management and disposition |

| Axis 1 | ||

| Clinical disorder due to a general medical disorder | Organic | Medical |

| Delirium, dementia and amnestic and other cognitive disorders | Organic | Medical |

| Substance-related disorder – intoxication or withdrawal disorder | Organic | Medical |

| Substance-related disorder – substance induced persistent disorder | Organic | Psychiatric |

| Clinical disorder (not identified to above or axis II principal diagnosis) | Psychiatric | Psychiatric |

This patient group is diverse and many factors increase the difficulty of assessment including poor cooperation, intoxication, violence and minimal information referrals. Additionally, many presentations are subtle, can mimic other conditions and may not have absolute or clear distinguishing criteria. The historical approach of ‘medical clearance’ aims to screen for emergent medical causes that are unsuitable for psychiatric care. Medical issues are traditionally called organic. That terminology persists but is increasingly challenged by a postulated medical basis for some psychiatric disorders. Medical clearance has been used for over 30 years, but there is still no accepted universal agreement of what that means or should entail. Overall, the process should be considered an imperfect risk reduction strategy.

General approach

Patients with abnormal behaviour labelled as psychiatric after routine medical and psychiatric assessment frequently have a final diagnosis of a medical cause or precipitant for the mental disorder. The incidence of missed medical diagnosis ranges between 8 and 46% [1–3]. One study of first psychiatric presentations found a higher rate of medical diagnosis of 63% [4]. Deciding whether a particular presentation of mental disorder is medical or psychiatric is often difficult, as there are very few absolutes that distinguish medical from psychiatric illness. Careful collection and weighting of appropriate information commonly only leads to a differential diagnosis.

Some diagnoses and dispositions can be determined quickly after a medical and psychiatric history, with the addition of a mental state and full physical examination. This may sometimes take place without expensive diagnostic procedures. Other presentations are difficult and require extensive and intensive evaluation, repeat evaluation, observation in hospital and significant investigations before the diagnosis is clear.

Medical clearance in emergency departments (EDs) can be inaccurate due to the presence of intoxicating substances or patient factors that limit necessary assessments. A non-judgemental approach with prudent intervention based on known or likely risks, close monitoring in a safe environment and repeated reassessment of physical and mental state over time are often necessary to obtain an accurate diagnosis and optimal outcome.

Studies on medical clearance by ED staff, primary-care physicians and psychiatrists have repeatedly shown a poor ability to discover medical conditions. This failure is commonly due to one or more of the following factors: inadequate history; failure to seek alternative information from relatives, carers and old records; poor attention to physical examination, including vital signs; absence of a reasonable mental state examination; uncritical acceptance of medical clearance by receiving psychiatric staff; and failure to re-evaluate over time [5]. One study noted that medical conditions were most easily identified in the ED by the triage nurse or medical officer asking whether any medical conditions existed in addition to the patient’s psychiatric complaints [6].

Evaluation requires a thorough approach and a commitment of time and effort. Special skills are required for medical clearance and psychiatric interview. A coordinated and focused medical and psychiatric assessment has the highest yield of correct diagnoses [1]. Proformas or clinical pathways may improve compliance and documentation of important details, but have not been clearly demonstrated to improve patient outcomes [7].

National Emergency Access Targets (NEAT) in Australia will change the management of mental disorder clients. The approaches will vary dependent on institutional capabilities and local agreements. Universal medical clearance for every patient presenting will be unlikely, with many known psychiatric patients being triaged directly for psychiatric assessment. Additionally, medical processing when required will need to occur concurrently with psychiatric assessments, thus replacing traditional sequential processing where medical assessment and often investigation precedes psychiatric involvement. High yield presentations for organic disease will be directed to Medical Assessment Units when available to allow investigations, observation and reassessment over a reasonable period of time.

Triage

Triage is vital, as many patients presenting with apparent psychiatric problems have medical conditions. Correct identification at the point of entry by nursing staff facilitates correct management and reduces morbidity and mortality. Many patients with psychiatric illness are also a significant risk to themselves or others and require urgent intervention. Questions regarding safety should always be raised (Table 20.2.2) [8].

Table 20.2.2

Is the patient a danger to him- or herself?

Is the patient at risk of leaving before assessment?

Is the patient a danger to others?

Is the area safe?

Does the patient need to be searched?

Pollard C. Psychiatry reference book – nursing staff. Hobart: Department of Emergency Medicine Royal Hobart Hospital; 1994 with permission.

Nursing staff should use a triage checklist to identify likely organic presentations (Table 20.2.3). These are indications for urgent medical assessment. If these are absent and a psychiatric diagnosis is likely, then an appropriate urgency rating by Australasian Triage Scale for psychiatric presentations should be applied. This triage categorization for psychiatric presentations has been developed and verified and allows reasonable waiting time standards for urgency to be applied in Triage Category 2–5 (Table 20.2.4) [9]. A Triage Category 1 when there is severe behavioural disturbance with immediate threat of serious violence has been sensibly added to that scale by the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine.

Table 20.2.3

High-yield indicators of organic illness

First presentation of mental disorder or distinctly different mental disorder in patient with known psychiatric illness

Delirium

Abrupt onset change in mental state

Hours to days

Fluctuates

Change in cognition

Disorientation

Memory deficit

Language disturbance

Disturbance of consciousness

Fluctuating or decreased

Poor attention

Perceptual disturbance

Hallucinations (especially visual)

Illusions

Misinterpretations

Drug or alcohol use

Recreational/illicit

Overdose

Prescribed or over-the-counter

Recent or new medical problems

Neurological signs or symptoms

Abnormal vital signs

Table 20.2.4

Guidelines for Australasian Triage Scale coding for psychiatric presentations [9]

Emergency: Category 2

Patient is violent, aggressive or suicidal or is a danger to self or others or requires police escort

Urgent: Category 3

Very distressed or acutely psychotic, likely to become aggressive, may be a danger to self or others. Experiencing a situation crisis

Semi-urgent: Category 4

Long-standing or semi-urgent mental health disorder and/or has a supporting agency/escort present (e.g. community psychiatric nurse*)

Non-urgent: Category 5

Long-standing or non-acute mental disorder or problem, but the patient has no supportive agency or escort. Many require a referral to an appropriate community resource

*It is considered advantageous to ‘up triage’ mental health patients with carers present because carers’ assistance facilitates more rapid assessment.

Triage should consider patient privacy issues if the history obtained is to be accurate. Collateral information from the carers with the patient should always be diligently obtained, carefully considered and documented. This information should allow the patient to be placed in an appropriate and safe environment where continuing visual and nursing observations can occur while further assessment occurs. An emerging trend is to use nursing triage immediately to refer likely psychiatric presentations to mental health clinicians without formal medical clearance. This method identifies clients who have presented with an aggravated or past similar psychiatric condition, who have normal vital signs, without recent medical concerns and who are not under the influence of drugs or alcohol. This streaming will become more widespread with National Emergency Access Targets and appears effective and efficient for both patient and clinicians. These triage referral systems require a medical safety net if referral was inappropriate. They have been operating now for some years without obvious increase in adverse outcomes. They are yet to be validated by scientific studies.

The interview environment

A climate of trust is very important, as many details of the psychiatric interview are quite sensitive. The psychiatric interview should take place in as quiet and private an environment as possible. The choice of the interview site may be limited in emergencies to ensure safety for both patient and staff.

History

A careful traditional medical history is the most common identifier of medical illness as a cause of a mental disorder presentation. Substance-related disorders are also most easily identified on history. A careful drug history, including prescribed, recreational and over-the-counter medications, should always be included. A slow onset and a previous psychiatric history are more commonly associated with psychiatric illness. Conversely, rapid onset, no premorbid decline and no past psychiatric history favour a medical cause. Poor recall of recent events may indicate delirium.

Family history is often a key indicator of psychiatric or medical cause. For example, a newly depressed 30-year-old man with a family history of Huntington’s disease or porphyria is more likely to have a physical cause. Conversely, an 18-year-old man with a hypomanic presentation and a strong family history of bipolar disorder is more likely to have a psychiatric cause. Suicidal and homicidal risk should be assessed routinely to ensure safety. Escalating immediate risk can often be recognized by combining patient perceived lethality and inquiry about any transition from thoughts, to actual plans and finally to actions. For patients with previous psychiatric illness, the system review is a useful screen for organic illness.

HIV is an increasingly important area as HIV-related illness becomes the new great mimic of modern psychiatry and medicine. Practices likely to have put the patient at risk should be explored. These may have been in the distant past. Known positive HIV status always warrants assessment for an organic cause of any new behavioural disturbance. Clinically, these problems often initially present with symptoms of mild anxiety or depression. Many treatable medical causes are only evident after significant investigations.

Delirium, a highly specific but not absolute indicator of medical or substance-induced disorders, should always be sought. By definition, this requires a history of recent onset and of fluctuation over the course of the day. Classically, there will be subtle changes in level of consciousness or the sleep–wake cycle. Patients may not be able to attend sufficiently to give this history if delirious. The psychiatric history, including life profile, may give evidence of the presence or absence of premorbid decline. An abrupt onset of abnormal behaviour with no premorbid decline is more suggestive of an organic cause.

Collateral history

Collateral history is important as the patient is not always capable of or willing to give full information. This history often crystallizes a diagnosis that would otherwise be uncertain or completely missed. Previous discharge summaries may provide relevant information regarding alcohol and drug use, previous behaviour and diagnosis. The family should be asked to bring in all medications, including over-the-counter items. Family, friends and caregivers may give more rapid access to collateral history than waiting for past admission details. Family and friends may be the only source for obtaining a history of a patient’s fluctuating mental status suggesting delirium, even when the patient appears quite lucid in the ED.

Examination

Lack of attention to important details of the examination is a frequently identified cause of missed medical illness. Areas that commonly yield positive findings, but which are frequently omitted, are the neurological examination, a search for general or specific appearances of endocrine disease, the toxidromes, examination for signs of malignancy, drugs or alcohol abuse and vital sign examination. Poor cooperation can prevent detailed examination and should be documented so that future consulting clinicians are aware of a deficient entry examination.

Vital signs

Abnormal vital signs are frequently the only abnormality found on examination of patients with serious underlying medical disease. They must always be acknowledged and explained. Pulse oximetry should be included rapidly to exclude hypoxia. A bedside blood sugar level should be routine for patients with abnormal behaviour.

Mental state examination

This is an account of objective findings of mental state signs made at the time of interview. It is the psychiatric equivalent of the medical examination and specifically details the current status. Observations made by other staff in the department, such as hallucinations, may be very significant and can be included with the source identified. Careful consideration of the mental status frequently clearly distinguishes medical from psychiatric illness and guides further investigation and management. For example, the presence of delirium or other significant cognitive defects make an organic illness almost certain. Disorientation is highly suggestive of delirium. Delirium can be very subtle. Sometimes, owing to the fluctuating nature, the patient may appear normal on a single interview. Other less obvious features, such as lability of mood, variability of motor activity or lapses in patient concentration making the interview more difficult, can be the only clues and can be easily overlooked. The importance of formulation using collateral history and repeated mental state examination is stressed. Documentation is important so that mental status changes with time during repeat assessment can be appreciated.

Examination tools

Cognitive defects may be rapidly and reliably identified in the ED during mental status examination by the use of Folstein’s Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) [10]. A score of less than 20 suggests an organic aetiology. A fall of two or more points on serial MMSE is highly suggestive of delirium. Elderly patients with delirium or cognitive defects are frequently not recognized by emergency physicians. These patients are at high risk of morbidity and mortality [11]. Simple assessment methods, such as the confusion assessment method (CAM), are rapid, reliable methods of identifying delirium in older patients, suitable for ED use [12]. Use of such simple methods should be encouraged to reduce inappropriate disposition. The tests above are suitable screening tools for EDs but are not intended to replace formal neuropsychological assessment. Proformas of medical history, mental state examination and physical examination may improve thoroughness of assessment and documentation.

Investigations

Investigations should always be guided by clinical findings and must be tailored to each individual presentation. A combined Massachusetts Emergency Physician and Psychiatry Task Force in 2009 identified criteria for low medical risk. Patients must meet all criteria. The criteria were adults aged 15–55, no acute medical complaints, no new psychiatric or physical symptoms, no evidence of substance abuse pattern, normal vital signs, normal gait and speech with normal memory and concentration. Patients with low medical risk were not recommended for any routine testing in the ED as they are of very low yield.

First presentations and suspicion of a medical cause that needs to be confirmed or excluded are the major indications for emergency investigations. Baseline blood tests, such as full blood profile, blood sugar level, electrolytes, liver function tests, calcium and thyroid function tests, may at times detect clinically unsuspected problems. Examination and culture of urine and cerebrospinal fluid should be undertaken if occult infection is considered a possible cause. A urine drug screen may on occasion be the only way to confirm clinical suspicions of drug-related illness. Time delays for results, low specificity from cross-reactivity and uncertainty caused by drugs with long half-lives limit their usefulness. Newer drug-screening stat tests at the bedside may improve their usefulness in the ED. Mandatory brain computed tomography (CT) is not indicated, but the threshold for imaging in first presentations of altered mental state without obvious cause should be low. HIV and syphilis testing should be done on all patients with significant risk profile. Herpes encephalitis may not produce imaging changes but should be considered when fever, delirium or cognitive changes are present with sudden alterations in behaviour. Newer imaging modalities, such as magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, positron emission tomography and single-photon emission CT, continue as research tools but may have a role in the future. Electroencephalogram examination is rarely a current ED test for psychiatric patients.

Diagnostic formulation

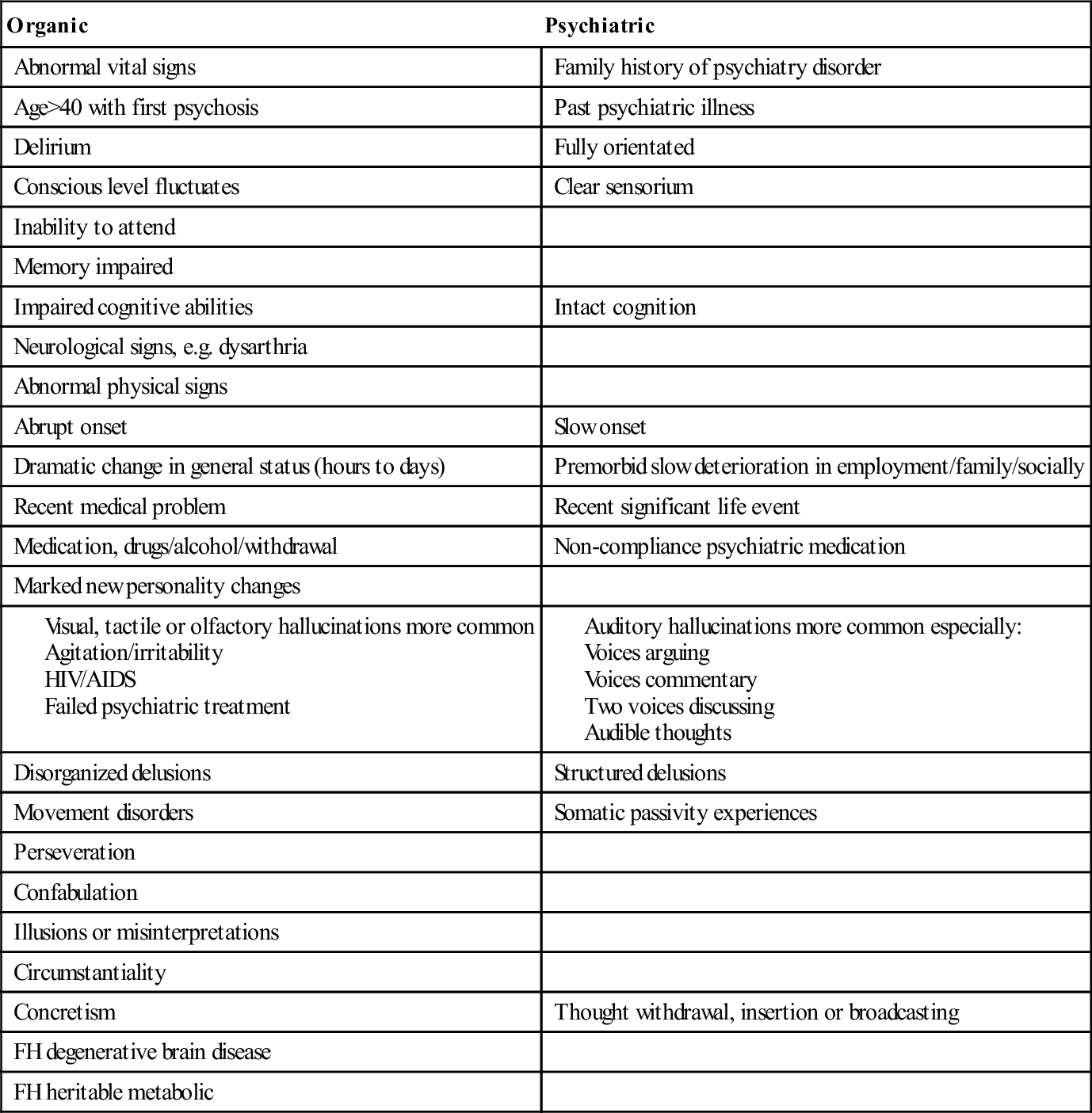

Emergency physicians should suspect organic disease until proved otherwise. In particular, reversible medical causes of abnormal mental state should be sought. Proformas improve documentation and summation. Consideration of the factors in Table 20.2.5 may help to determine doubtful cases. There are few absolutes that distinguish organic from psychiatric patients. Use of the five-axis DSM-IV system improves the ability to look at the patient’s presentation in the context of total functioning. It also allows emergency physicians to communicate with psychiatric peers in the recognized language.

Table 20.2.5

Factors influencing the likelihood of medical or psychiatric illness as the principal diagnosis

Some patients require periods of observation, re-examination and further investigations before a definitive answer is obtained. Intoxicated patients frequently are not assessable till sober. NEAT will pressure hospitals to look for safe disposition sites for this often difficult patient group. Interim care and disposition varies depending on presentation, prior history and facilities available. A common expectation of emergency physicians for patients referred to psychiatrists is to document that the patient is ‘medically cleared’. The assessment is known to be imprecise and difficult [1–4,7]. Better documentation is to state that the ED assessment has revealed no evidence of an emergent medical problem that would preclude admission to psychiatric care.

Conclusion

A thorough medical history, psychiatric history, collateral history, physical examination, mental state examination and judicious specific investigation will identify most patients likely to have an underlying physical cause for a mental disorder presentation. Omission of any of these steps may lead to missed medical diagnosis and incorrect disposition.

20.3 Deliberate self-harm/suicide

Jennie Hutton, Grant Phillips and Peter Bosanac

Introduction

Suicide is a deliberate act of intentional self- inflicted death. It is the most extreme manifestation of deliberate self-harm, where the spectrum also comprises suicidal ideation, plans and intent. Although suicide is uncommon, 10% of people who commit suicide are seen in an emergency department (ED) in the month prior to death, with a substantial proportion not having psychosocial assessment, thus providing an opportunity for intervention [1,2]. The major ED impact, however, is in the identification and assessment of large numbers of patients potentially at risk of suicide, with initial management of co-morbidities and modifiable risk factors.

Deliberate self-harm (DSH) is a maladaptive response to internal distress and may not have suicidal intent; it may, however, indicate a risk for suicide. Deliberate self-harm is a common ED presentation (approximately 0.4% of all ED visits [3]) and the goals of management include treatment of the physical health sequelae, assessment of risk of non-fatal or fatal repetition and diagnosing and commencing treatment of potentially reversible psychosocial causes.

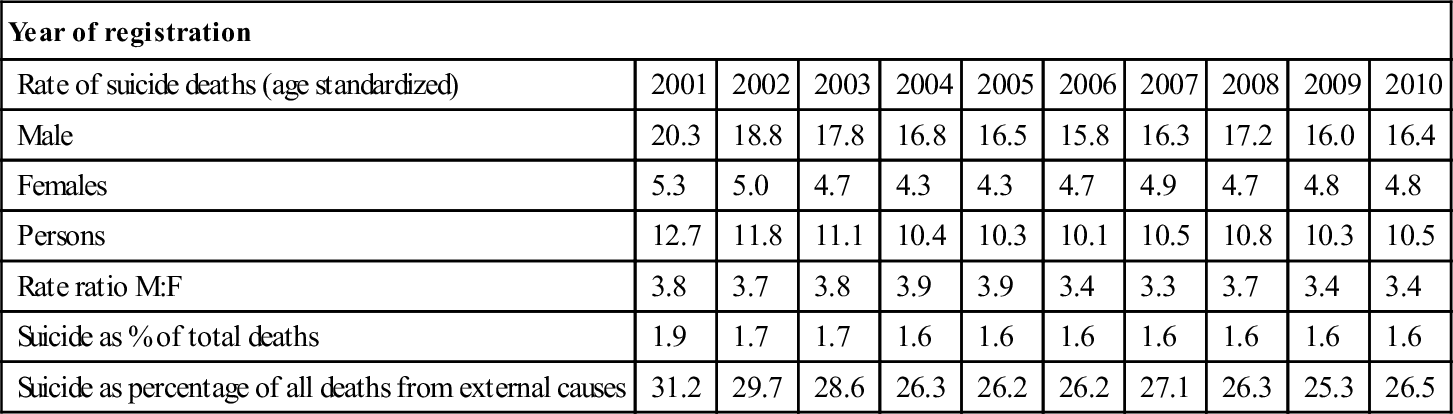

Epidemiology

In Australia, there were approximately 2300 deaths per year from suicide in 2010, with age-standardized rates of approximately 16.4 per 100 000 in males and 4.8 in females (Table 20.3.1) [4]. Suicide accounts for 1.6% of deaths in Australia. Suicide remains the leading cause of death among Australians between 15 and 34 years of age. Despite some decreases in suicide rate over the past decade, suicide remains a major external cause of death, accounting for more deaths than road traffic crashes [5].

Table 20.3.1

Suicide summary statistics, Australia, 2001–2010 [6]

| Year of registration | ||||||||||

| Rate of suicide deaths (age standardized) | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 |

| Male | 20.3 | 18.8 | 17.8 | 16.8 | 16.5 | 15.8 | 16.3 | 17.2 | 16.0 | 16.4 |

| Females | 5.3 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.8 |

| Persons | 12.7 | 11.8 | 11.1 | 10.4 | 10.3 | 10.1 | 10.5 | 10.8 | 10.3 | 10.5 |

| Rate ratio M:F | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 3.4 |

| Suicide as % of total deaths | 1.9 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| Suicide as percentage of all deaths from external causes | 31.2 | 29.7 | 28.6 | 26.3 | 26.2 | 26.2 | 27.1 | 26.3 | 25.3 | 26.5 |

OECD Factbook 2009. [Internet homepage] [cited 2012, Nov 4].<http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/oecdfactbook-2009/suicide-rates_factbook-2009-graph162-en>

Across OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries, suicide rates were lowest in Greece, Mexico, Italy, the UK and Spain at less than 7 deaths per 100 000. They were highest in Hungary, Japan, Korea, Finland and Belgium at more than 19 deaths per 100 000 [6]. WHO estimates the low and middle income countries account for 84% of global suicides with India and China accounting for 49%. In these countries, rural young women are at an increased risk of suicide [7].

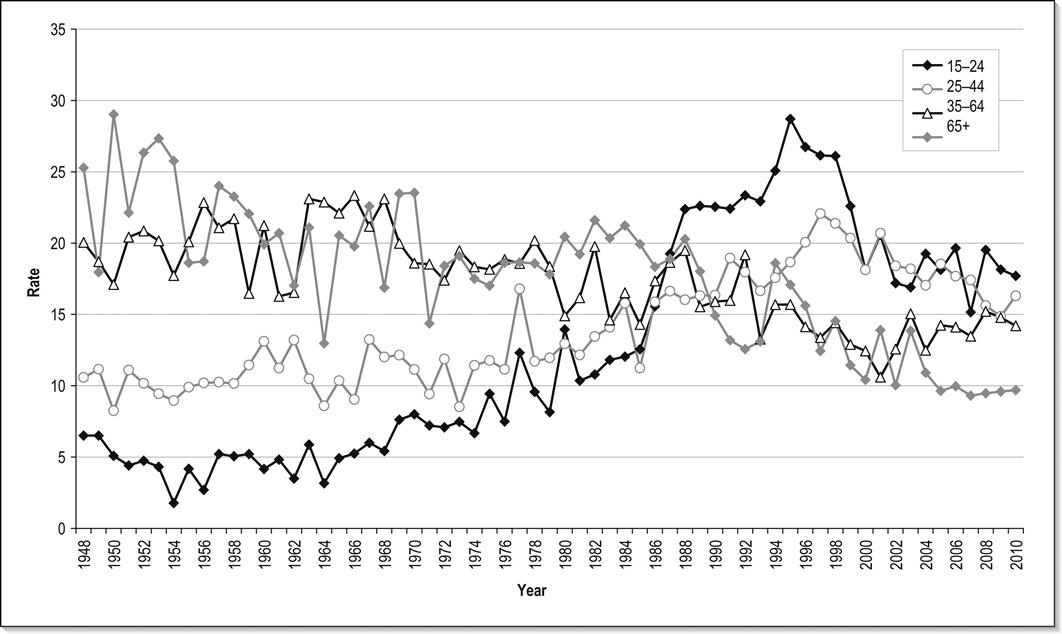

The trends involving completed suicide vary internationally, as well as subnationally, in addition to variance over time. Figure 20.3.1 shows this change over 62 years for New Zealand. Some inconsistencies across reporting systems should also be considered when interpreting suicide rates.

Hospital presentations for DSH are at least 10 times higher than suicide rates [4]. In the 2007 Australian National Survey of Mental Health, 0.3% of males and 0.5% of females reported they had made a suicide attempt in the previous 12 months. Most of these are not reported or are reported as accidents. Hence, unrecognized DSH is at least as frequent as that recognized. The same survey reported 1.9% of males and 2.7% of females experienced suicidal ideation within 12 months [8]. This rate may be as high as 25% in certain populations and age groups [9,10].

Risk of suicide

An episode of DSH is one historical risk factor predictive of future suicide attempts. Approximately 1–2% of patients commit suicide during the year following an attempt and in approximately 40% of suicides there is a history of a previous self-harm. A systematic review of fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm reported a suicide rate of 2% at 1 year and 7% after 9 years [11]. In a prospective Finnish 14-year follow-up study and a UK 18-year follow-up study, the rate of suicide after an episode of DSH was 6.7% [12,13]. A 10-year follow-up study in New Zealand documented a suicide rate of 4.6% in patients admitted for DSH [14]. An emergency centre-based retrospective cohort study in New Zealand demonstrated an 18% re-presentation and a 1.1% suicide rate at 1-year follow up [15]. Hospitalization and aftercare decrease short-term risk of suicide, but have little impact on long-term risk of suicide. However, this may be due to undertreatment of psychiatric illness [16–18].

Exposure to suicide in adolescents tends not to cause an increased risk of suicide among friends, but may cause an increased incidence of depression anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder [19].

Repeated episodes of DSH

DSH usually invokes help from friends, family and the medical profession so that the patient’s social situation and psychological well-being tends to improve [20]. This effect is prominent in younger patients, but may not occur in patients aged over 60 years [21]. The risk of repetition is 12–16% in the following year, with 10% of these occurring in the first week [11]. This is more likely in females who are unemployed, have cluster B (e.g. borderline, narcissistic and histrionic) personality traits or have substance-abuse problems. A younger age at first attempt, presence of long-standing affective disorders, drug/alcohol misuse disorders and anxiety all correlate with repeated attempts. Some patients have chronic suicidal ideation and multiple repetitions of DSH. They often suffer from personality disorders, psychotic disorders, chronic medical conditions, alcohol or drug use, a history of childhood sexual abuse [22,23] and violent behaviour. They use DSH as a means of fighting off anxiety, hopelessness, loneliness or boredom, or for inter-personal secondary gains with regard to family, friends or healthcarers. These patients are at increased risk of eventual suicide. Reversible potentiating factors should be addressed where possible.

Patients with DSH who leave the ED prior to a psychosocial assessment may have a higher risk for repeat DSH, probably associated with lack of specialist follow up and treatment of reversible factors [18,24].

Increased mortality

A suicide attempt is associated with a severe risk of premature death with the increased mortality rate not entirely due to suicide [25]. There is a higher than expected rate of accidents, homicides and death from other medical conditions. This may indicate social disadvantage, disengagement with the health system, underlying chronic illnesses or lifestyle factors.

Patient characteristics

Demographic factors

Age

Suicide and DSH are rare in children under 12 years of age. Australian data suggest similar rates of suicide from the age of 20–50, with a peak at 40–44 years in males (27.7 per 100 000) and 45–49 years in females (7.6 per 100 000) [4]. There is another peak in the elderly, with suicide rates increasing with age from 65 years. This bimodal distribution is also evident from USA and New Zealand data, with males aged over 80 years having the highest age-specific rates of suicide.

The incidence of DSH increases throughout puberty, reaching a peak at 15–24 years of age and decreasing thereafter. The ratio of rates of DSH to suicide decreases markedly with age. DSH is uncommon in the elderly, who have a high ratio of successful to unsuccessful attempts [26].

Gender

In Australia, the overall rate ratio of M:F suicide is 3.4 in 2010 compared with 2.7 in New Zealand and 3.2 in the UK in the same year [27,28]. The rate for male DSH has been increasing in Western countries recently with the male to female ratio approximately 1:2. Females choose methods that are less likely to be fatal and may be more likely to present to hospital following DSH.

Employment

Unemployment increases the risk of DSH by 10–15 times, with the risk increasing with duration of unemployment. This may not be a cause or effect, but may be due to some underlying factor, such as psychiatric illness, personality disorder or substance abuse. There is a more pronounced increased in the risk factors of unemployment rate and lower socioeconomic status for young men in Australia [29].

Social and cultural factors

Suicide rates are higher in those who live alone or are in a lower social group, especially in urban areas characterized by social deprivation and overcrowding. Being single, separated, divorced or widowed increases the risk of suicide two- to threefold in the high- income countries [7]. In these countries, being partnered reinforced by children decreases the risk of suicidal behavior. In India and China, there is a reduced risk of suicide versus other causes of death in women widowed, divorced or separated compared with married women and men [7].

Recent data in Australian Aboriginal people report substantially higher suicide rates that commence at a lower age than in the non-Aboriginal population [4]. Suicide has become more common in recent years; in 2010 the percentage of deaths by suicide among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people was 4.2% compared with non-indigenous Australians 1.6% (does not include states of Victoria, Tasmania and Australian Capital Territory data). It is of concern that the age-specific suicide rate for Aboriginal males aged 25–29 was 90.8 deaths per 100 000 in a combined 10-year period 2001–2010 [4]. A higher suicide rate is seen in indigenous groups of other developed countries, for example, in New Zealand, the age standardized rate was 16 per 100 000 in 2010 compared with a rate of 10.4 in the non-Maori population [28].

Suicide rates of migrants initially reflect rates in the country of origin and converge toward the Australian rate over time. Rural areas in Australia and New Zealand and remote areas in the UK have a higher rate than urban areas [4,28,30]. Incarceration is a risk factor for suicide; in any form of custody, the suicide rate is three times that of the general population [31].

Some social groups, such as doctors, dentists, musicians, lawyers and law-enforcement officers, are more prone to suicide [32]. Most adults (75%) with DSH have relationship problems with their partners and teenagers with their parents. A major argument or separation often precedes the act on a background of ongoing social difficulties or substance use.

Medical factors

There is an increased risk of suicidal ideation in people with chronic ill health, terminal illness or chronic pain and epilepsy. The majority of such patients have sought medical advice in the 6 months before suicide. Most patients with DSH have good health.

Psychiatric factors

There is a pre-existing psychiatric disorder in 90–100% of cases of suicide, with depression accounting for 66–80%, but this rate may be based on retrospective psychological autopsy and therefore be open to dispute. The lifetime rate of suicide among psychiatric inpatients is 3–12 times higher than in the general population and involves a greater proportion of more violent methods, such as jumping from buildings, hanging or jumping in front of vehicles. One-third of these episodes occur after self-discharge from hospital, with another third occurring during approved leave. The high-risk time is the first week of admission and during the first 3 months after discharge [33].

Psychiatric disorders are present in up to 60% of patients who commit DSH, but may be transient and secondary to acute psychosocial difficulties. Da Cruz et al. examined the cases of 286 individuals who died within 12 months of mental health contact in North West England; 43% of the sample attended the ED on at least one occasion and 12% of the sample attended an ED on more than three occasions and could be considered ‘frequent attenders’. Most frequent attenders had a history of self-harm (94%), 68% had a history of alcohol abuse, 63% were unemployed at the time of deaths and 49% had a history of drug abuse [34].

Affective disorders

The psychiatric diagnosis that carries the greatest risk of suicide is mood disorder, particularly major depressive disorder if associated with borderline personality disorder, anxiety or agitation [35]. Fifteen per cent of these high-risk patients commit suicide over a lifetime. Depression correlates well with the occurrence of suicidal desire and ideation, but may not be as strong a predictor of planning and preparation (intense thoughts, plans and capability) and, therefore, suicide completion [36]. Hopelessness is the most important factor associated with suicide completion and may be of greater importance than suicidal ideation or depression itself [36]. Depressed patients should, therefore, have their attitudes towards the future carefully assessed.

Substance abuse

Individuals with alcohol use disorders have an overall approximately 7% lifetime risk of dying by suicide, with women being at greater risk than men. Fifteen per cent of alcohol-dependent persons eventually commit suicide. The majority of these are also depressed. The risk is higher if associated with social isolation, poor physical health, unemployment and previous suicidal behaviour. The increased risk may be more pronounced in males aged below 35 years [37]. Young males dependent on heroin have 20 times the risk of the general population. Chronic alcohol dependence is uncommon in DSH, but alcohol intoxication is involved in 50–90% of suicide attempts. Wyder found that 65% of people presenting with deliberate self-harm in Australia were substance affected at the time [38]. Acute alcohol ingestion is found in approximately 35% of people who die by suicide and between 15 and 60% of people who die by suicide have been found on psychological autopsy to have lifetime alcohol-use disorders [39].

Schizophrenia

Up to 10% of people with schizophrenia die by suicide. Young adult males are at high risk, especially if there is associated depression with feelings of hopelessness, previous DSH or suicide attempts, unemployment or social isolation.

Personality disorders

Patients with cluster B personality disorders are at high risk of DSH and suicide, especially if associated with labile mood, impulsivity, alienation from peers and associated substance abuse. This may be due to precipitation of undesirable life events, predisposition to psychiatric and substance-abuse disorders and social isolation. Adjustment disorders are associated with 25% of adolescent suicide [23].

Frequent attenders

Frequent attenders to EDs (defined as greater than three presentations in a year) are also at high risk. This group has seven times the risk of the general population and rates of suicide similar to clinical psychiatric populations. This risk is particularly pronounced in patients who present with panic attacks, especially if associated with depressive symptoms.

Aetiology

No specific psychological or personality structure is associated with suicide and patients who commit suicide or DSH do so for many unrelated reasons. The precipitant may be a personal crisis or life change amplified by poor social support, substance abuse or psychiatric disorder. Intoxication may decrease inhibitions enough to allow an act to proceed. A study by Wyder interviewed 112 people following a deliberate self-harm attempt. She found that 51% had considered deliberate self-harm for 10 minutes or less, but of those who had been affected by alcohol that number jumped to 93% [40].

The most frequent methods of suicide in Australia are hanging, strangulation and suffocation, these modes being used in 56% of all suicide deaths in 2010 in Australia. Poisoning by drugs was used in 12% of suicide deaths in 2010, followed by poisoning by other methods including alcohol and motor vehicle exhaust (10%). Firearms accounted for 7% of suicide deaths in Australia in 2010, a rate which has declined from 20% a decade prior, possibly due to firearm restriction legislation [5]. Proportions due to each method vary according to region, residence, age and sex [1,41]. In the USA, firearms accounted for 57% of male and 32% of female suicide deaths. In trauma centres in the USA, stab wounds are a far more common method of deliberate self-harm than gunshot wounds and people (more often men) at the extremes of age are more likely to use firearms with fatal consequences [3]. In many developing countries, organophosphate or antimalarial poisoning and charcoal burning are more common methods of suicide [42]. One-third of patients with DSH express a wish to die, but most do so to communicate distress. DSH may serve many functions for the person. At its most simple, it serves an integrative function calming the person at a time of great distress. It may also be a way of mobilizing assistance for someone who is feeling overwhelmed by circumstances. Many patients threaten suicide or magnify being at risk of suicide to increase the likelihood of admission to hospital. These patients are more likely to be substance dependent, have personality diatheses (for example, marked borderline, antisocial or dependent traits or disorder) or homelessness and be unpartnered and in legal difficulty. However, these instances of goal directed behaviour should not be discounted and the behaviour should be taken seriously. A presentation to an ED is a declaration that the person is in a self-defined crisis for which they are using maladaptive coping measures.

Most cases of medically serious DSH are due to self-poisoning, with 90% associated with alcohol intoxication. The most common drugs are non-prescription analgesics and psychotropic drugs. Many overdoses are related to alcohol or illicit substance intoxication and may be accidental rather than deliberate, although this distinction is often difficult to ascertain. Self-injury may involve cutting of the skin in various sites about the body but may also involve self-inflicted cigarette burns, excoriation of the skin or hitting themselves or other objects. More violent forms of self-injury are less common and suggest serious suicidal intent. Bizarre self-mutilation may occur in psychotic patients who may not necessarily have an intention to die but are acting in accordance with delusional beliefs or in response to command hallucinations.

Assessment

A person who expresses suicidal ideation or engages in DSH is sending a distress signal that emergency physicians must acknowledge. Suicidality should also be assessed in patients with symptoms or signs of depression, unusual behavioural changes, substance abuse, psychiatric disorders, complainants of sexual violence [27] and those who present with injuries of questionable or inconsistent mechanism, such as self-inflicted lacerations and gunshot wounds or motor vehicle accidents involving one victim. Many would argue that assessment of suicidality should be a routine part of any ED assessment. A retrospective study by Da Cruz et al. found that 40% of persons who died by suicide had presented to the ED at least once during the year prior to their death [34]. Assessment in the emergency department ideally will contain elements that provide the person with the opportunity to discuss psychosocial aspects of their life. Within this discussion, it may be that suicidal ideation or thoughts of deliberate self-harm may be elicited. This may allow early referral to psychosocial supports thereby providing the person with holistic care to help address their needs.

Assessment requires a systematic, multidisciplinary approach involving prior staff education, appropriate triage, observation and restraint procedures (in the setting of imminent risk and the absence of less restrictive options) and a planned strategy for assessment followed by treatment and disposition. The priorities are to define the physical sequelae of the act, risk of further DSH behaviour, psychiatric diagnoses and acute psychosocial stressors. These aspects are those that can then be targeted for short-term interventions.

Triage

In a patient who has attempted DSH, initial management involves resuscitation, treatment of immediate life threats and preventing complications. The patient should be triaged according to the physical problem as well as current suicidality, agitation and aggressiveness and mental state. The mental health triage scale can be used for this purpose [43]. A triage score of 2 or 3 should be applied if patients are violent, actively suicidal, psychotic, distressed or at risk of leaving before full assessment can occur. Constant observation is required at this point and nursing staff, security or police may be needed. In Australia, a number of different triage scales can be used. There is some evidence that a mental health triage scale improves outcomes; however, the accuracy of the assessment can be limited by a number of environmental, staff and patient factors [44].

Medical assessment

The patient’s safety in the ED should be optimized by limiting availability of drugs, removing sharp implements, removing car keys, ropes, belts or sheets and securing nearby windows. Other concurrent and concealed methods of self-harm should be sought. This may be facilitated by changing into hospital gowns, whereby the patient is more easily identified if they abscond. In addition, other means to increase visibility, such as security cameras, high visibility cubicles or assigning a special nurse, should be considered. Assessment of the patient may be difficult, either due to a general medical cause or being unsettled from the precipitant of the act, or from not wanting to be in hospital or allow medical intervention. This may necessitate the therapeutic utilization of anxiolytic medication; the use of physical restraint may be considered if at high risk or unable to be fully assessed and wanting to self-discharge. This may be done under a duty of care to the patient or the local mental health act may be utilized in extreme situations. Emotional support of patient, friends and relatives is required during and after this phase, with clear explanation of the rationale and the procedures. Distinguishing medical from psychiatric causes of mental disorder presentations is discussed elsewhere in this book (see Chapter 20.2).

Suicide risk assessment

Initially, an assessment needs to be done in the ED so as to determine patient disposition, but a more comprehensive psychiatric assessment may need to wait until substance or anxiolytic medication effects wear off. Other sources of information need to be accessed since patient history can be unreliable or incomplete. Friends, family, local doctor, ambulance officers, helping agencies already involved and previous presentations documented in the medical record can all add useful information in order to advise an assessment. A therapeutic relationship should be formed and the clinician should be non-judgemental, non-threatening and clearly willing to help. A positive attitude has been shown to improve outcomes with this group of patients [45]. People presenting in crisis are hypersensitive to any negative transference. This may intensify the patient’s already low self-esteem, increasing future suicide potential and making a therapeutic relationship difficult to establish [46]. When managing a patient who may be suicidal, the suicidal ideation should be discussed openly. Expressions of self-harm carry individual meaning for each person. It is important, in a therapeutic relationship, to explore the meaning that this carries for the person and alternatives.

Risk factors may be divided into two main categories, namely static and dynamic. Static factors have been historically identified by Durkheim [47] who showed some, less socially integrated groups within society to be at greater risk of suicide than others. These static factors are enduring and in context of a person’s developmental history and social circumstances. Hence, being male, unemployed, single, poorly educated, from a lower socioeconomic group, with a history of mental disturbance and substance-use disorders would all place someone in a higher risk group.

Dynamic factors are the more fluid day-to-day factors that intensify the risk posed by the static factors. Flewett [48] divides these factors into internal and external factors. The internal factors include current feelings of abandonment, desperation, hopelessness, co-morbid depression, current drug use or physical illness. External factors are those of increased social dislocation, including homelessness, bereavement, intoxication, adverse life event, such as the recent loss of a job or relationship.

The role of dynamic risk is highlighted by Rosenman [49] when he states:

for conditions with multiple risk factors… each factor adds a little to the risk, but only when it interacts with other factors. No single predictor or combination of predictors is present in every individual, and membership of the high risk group changes from moment to moment. Half a bottle of whiskey may create a high suicide risk within an hour.

Assessment of suicide risk involves assessing background demographic, psychiatric, medical and social factors, these are the static factors that underlie any presentation and will determine the chronic suicidal risk that the person presents. Dynamic risk factors as well as the current circumstances and risk of suicidal behaviour itself are outlined in Table 20.3.2. There are epidemiological differences between people who attempt suicide and those who complete suicide. Although the groups are different, there is an important overlap. The more an individual’s characteristics resemble the profile of a suicide completer, the higher the risk of future suicide or suicide attempts. Despite this, in long-term follow-up studies very few of these factors have been shown to be good independent predictors of suicide following DSH. The most consistent factors are psychiatric illness, personality disorder, substance abuse, multiple previous attempts and current suicidal ideation and hopelessness. Guidelines are available to assist in suicide-risk stratification and describe characteristics associated with suicide-risk levels and the appropriate further assessment and disposition for each group [50].

Table 20.3.2

Factors associated with suicide [1]

| Variable | High risk | Low risk |

| Static factors | ||

| Gender | Male | Female |

| Marital status | Separated, divorced, widowed | Married |

| Employment | Unemployed or retired | Employed |

| Medical factors | Chronic illness, chronic pain, epilepsy | Good health |

| Psychiatric factors | Depression, bipolar, schizophrenia, panic disorder, previous psychiatric inpatient, substance abuse | No psychiatric history |

| Social background | Unresponsive family, socially isolated or chaotic, indigenous background, refugee from conflict areas, past history of trauma, developmental trauma | Supportive family, socially stable and integrated |

| Dynamic factors | ||

| Suicidal ideation | Transient, intense suicidal ideation, plan and intent, intoxication and impulsivity with impaired judgement | Infrequent, transient |

| Attempts | Multiple | First attempt |

| Lethality | Violent, lethal and available method | Low lethality, poor availability |

| Planning | Planned, active preparation, extensive premeditation | No realistic plan, telling others prior to act |

| Rescue | Act performed in isolation, event timed to avoid intervention, precautions taken to avoid discovery | Rescue inevitable, obtained help afterwards |

| Final acts | Wills, insurance, giving away property | |

| Coping skills | Unwilling to seek help, feels unable to cope with present difficulties | Can easily turn to others for help, can plan to overcome present difficulties, willing to become involved in aftercare |

| Current ideation | Admitting act was intended to cause death, no remorse, continued wish to die, hopelessness or helplessness | Primary wish to change, pleased to recover, suicidal ideation resolved by act, optimism |

| Precipitant | Similar circumstances can recur, acute precipitant not resolved | Stressful but transient life event, acute precipitant addressed |

Use of scales

Many screening tools have been devised to identify high-risk groups within those presenting with DSH. PATHOS [51], the Suicidal Intent Scale [52], the Sad Persons Scale [53] and other scoring systems have been devised to complement medical assessment of suicide risk. However, many of these scales use outdated risk factors and patient populations unrepresentative of EDs. Scales need to be sensitive, but this misclassifies a large number of individuals as potentially at risk of suicide. These deficiencies need to be considered when applying suicide risk scales in the ED and these scales should not be used as an absolute assessment of suicide risk or of the need for psychiatric admission [54,55]. In addition to validated questionnaire assessment, there are a number of validated interview assessment tools, such as the Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview [56]. Problems clinicians report in using these tools is that of the time taken to administer them. In any event, these tools have been shown to be as accurate as a mental health clinician’s global assessment [9].

The problems associated with suicide-risk assessment are summarized in Table 20.3.3.

Table 20.3.3

Problems in assessing suicide risk

Suicide is rare, even in high-risk groups, so it cannot be predicted without a high rate of false-negative or false-positive errors

Suicidality presents in heterogeneous ways that may not be recognized

Suicidality is transient and affected by intoxication, stress and being in hospital

The patient may be reluctant, oppositional or manipulative

The patient may present in an atypical fashion, especially the elderly with physical complaints

Suicide risk factors identify high-risk subgroups but not individuals

The demographic factors associated with suicide have changed recently, thus changing the make-up of risk groups

Risk factors are based on studies of long-term follow up and, therefore, long-term risk

Subtle changes in mental status and behaviour may be missed if not assessed by the usual doctor

Unexplained improvement in psychological status may be the result of increased motivation to die

Patients may deny their true intentions due to embarrassment, fear of being stopped in carrying out their own wishes, fear of being institutionalized or fear of the confidentiality of the interview

Patients may say life is not worth living or that they feel they would be better off dead, but not necessarily have an increased risk of suicide, unless they have made suicidal plans or attempts, or if they have pervasive hopelessness

Correlation between medical danger and suicidal intent is low unless the patient can accurately assess the probable outcome of their attempts if treatment had not been received

Definitive treatment and disposition

Following necessary medical treatment and suicide-risk stratification, disposition may involve involuntary or voluntary admission to a psychiatric or medical ward, short-term observation or discharge with appropriate follow up. Restraint and involuntary admission may be necessary for the high-risk patient who wishes to self-discharge. Approximately 30% of DSH patients are admitted for psychiatric inpatient care, but the factors involved in the decision for psychiatric hospitalization following DSH involve a complex evaluation of risk, potential for treatment and social supports [57].

Patients who are intoxicated with alcohol can be both behaviourally disinhibited and emotionally labile and, as discussed, are at higher risk of intentional self-injury. Short-term observation allows intoxication to resolve so that more comprehensive and longitudinal psychiatric assessment can take place. A short-term stay in hospital can also help resolution of many acute areas of conflict and make psychiatric evaluation more accurate. ED short-stay wards or psychiatric assessment and planning units are appropriate for these admissions, especially if a multidisciplinary team is available to review the patient and institute management and follow up.

Important elements of management involve addressing the modifiable elements of the precipitating problem, treatment of psychiatric illness and environmental interventions, such as family counselling, encouraging a support network and developing coping and problem-solving skills [58]. Adaptive solutions to the current crisis should be reinforced utilizing short-term solutions. Factors that should be addressed while patients are in hospital include referral to services to help address the dynamic risk issues, such as problems with relationships, employment, finances, housing, legal problems, social isolation, bereavement, alcohol and drug abuse and dependence. In this regard, social workers or mental health nurses are invaluable [59]. For greatest effect, these should be available after hours and on weekends since the majority of DSH presentations are after hours [60]. For repeat attenders who are often socially isolated, hospitalization should not be a substitute for social services, substance-abuse treatment and legal assistance, although admission may be necessary while appropriate supports are put in place [61].

Dispositional decisions need to be taken, weighing up the relative and potential iatrogenic harm generated by hospitalization and the now common legal mandate for treatment in a least restrictive environment. Discharge will be with referral to community agencies with responsibility for supporting the person in the community and, according to risk assessment, may include community mental health teams, GPs, non-government support agencies, etc. The aim of disposition is to minimize risk factors while empowering the person to develop more positive and capable coping styles for future crises.

Pharmacotherapy has been shown to be useful in addressing the debilitating symptoms of a major depressive disorder and, along with psychotherapy, can help the person regain their previous level of functioning. Once risk and disposition have been addressed, the pharmacotherapeutic management and ongoing assessment can be by the local medical officer, who can refer as necessary to mental health specialists. Pharmacotherapy involves the treatment of the underlying psychiatric disorder. Antidepressants decrease the risk of attempting suicide, although the lethality of suicide attempts is increased if tricyclic antidepressants are taken in overdose. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and other newer classes of antidepressants (including SNRIs, NasSa, NRI, etc.) may have a more selective effect in decreasing suicidal behaviour and are less toxic in overdose than tricyclic antidepressants – the latter are no longer prescribed as first-line antidepressant medications by psychiatrists. These factors make the newer class of drugs an attractive choice for depressed patients who are suicidal.

Prevention

Comprehensive strategies for prevention of suicide have been or are being developed in Finland, Norway, Sweden, Australia and New Zealand [62]. Suicide prevention focuses on psychiatric, social and medical aspects and usually involves public education, media restrictions on reporting of suicide, school-based programmes with teacher education, training of doctors in detection and treatment of depression and other psychiatric disorders, alcohol and drug abuse information, enhanced access to the mental health system and supportive counselling after episodes of DSH. Decreasing the availability of lethal methods may involve legislative changes, such as more stringent gun control, restricting access to well-known jumping sites or changes to availability or packaging of tablets [63]. Overall, studies into the effectiveness of suicide-prevention strategies have shown inconsistent reductions in suicide rates following interventions [64]. Approaches to reduce DSH repetition have also shown disappointing results [65]. Improved recognition and treatment of mental illness, improved social services and drug and alcohol-support services may be of greater benefit than specific suicide-prevention strategies.