CHAPTER 20 Mental Retardation

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Prevalence

The prevalence of mental retardation is approximately 1%.1 Prevalence rates have varied between 1% and 3% depending on the populations sampled, the criteria used, and the sampling methods.

Currently, there are more than 750 known causes of mental retardation; however, in up to 30% of cases no clear etiology is found.2–6 This can be disheartening for patients, parents, families, and caregivers, as they search for an understanding of a condition that will profoundly affect their lives. This aspect of a patient’s history should be addressed at the start of treatment.

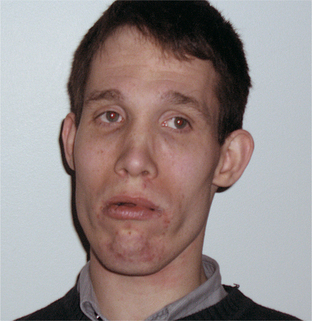

The three most common identified causes of mental retardation are Down syndrome, fragile X syndrome, and fetal alcohol syndrome. Facial features of these conditions are provided in Figures 20-1 through 20-3; knowledge of the dysmorphic features associated with clinical syndromes aids in their identification. Down syndrome is the most common genetic cause of mental retardation; it involves trisomy of chromosome 21. Fragile X syndrome is the most common inherited cause of mental retardation with the FMR1 gene located on the X chromosome. Fetal alcohol syndrome, the most common “acquired” cause of mental retardation, has no identified chromosomal abnormality, as it is a toxin-based insult. These three etiologies account for nearly one-third of cases of mental retardation.

CO-MORBID PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

Individuals with mental retardation experience the full range of psychopathology, in addition to some unique behavioral conditions.7–9 The rates of psychopathology in this population are roughly four times higher than in the general population2,6; exact determination is difficult as data collection in this area is confounded by methodological issues (including how to obtain an accurate assessment in the absence of self-report and determining how appropriate certain standardized measures might be in this population). In institutional settings up to 10% of individuals with mental retardation also have some form of psychopathology or behavioral disorder.

For many years there was an unwillingness on the part of psychiatrists to aggressively treat a difficult-to-diagnose population. This was superimposed on a movement in the field of mental retardation not to “over-pathologize” behavior. Related to this has been the problem of under-diagnosis, based on the concept of diagnostic overshadowing, that is, the attribution of all behavioral disturbances to “being mentally retarded.”10–12 This stance further marginalizes an already vulnerable population. However, in today’s treatment climate one must also be on guard against over-treatment in the form of misguided polypharmacy. What is needed is a thoughtful approach to diagnosis and treatment of both psychiatric and behavioral disorders in a challenging population.

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Features

Familiarity with the diagnostic criteria of mental retardation and its clinical manifestations will aid in the assessment of the functional strengths and weaknesses of a patient with mental retardation who presents for diagnosis and treatment. Table 20-1 presents the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria for mental retardation.1 These criteria have been adopted from work done by the American Association on Mental Retardation (AAMR), now called the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD). Key criteria include the following: below-average intellectual function (as defined by standard intelligence quotient [IQ] testing results that are at least 2 standard deviations below the mean [i.e., an IQ ≤ 70]), in conjunction with impairment in 2 out of 11 areas of adaptive function (compared to peers of the same age and culture), and the symptoms must have been present before age 18 (to denote the congenital nature and life-long course of the diagnosis and to differentiate mental retardation from acquired brain injury and other impairments in cognition that can occur later in life).

Table 20-1 also lists adaptive areas of function that are assessed when one considers a diagnosis of mental retardation. These domains were not empirically tested and no “gold standard” exists in terms of assessment of level of function. Multiple instruments are available to assist in the assessment; their use varies widely from state to state and from agency to agency. In addition, one can see individuals who may have been diagnosed as mentally retarded, but who do not meet strict IQ criteria. IQ testing can have a standard error of measurement of approximately 15 points. Conversely, there are individuals who may have had a diagnosis of mental retardation, but whose functional level and family support system have allowed them to live and work in society without need for services or supervision. Psychiatrists should be cognizant of the general cognitive level of their patients and assess how cognitive ability may affect their clinical presentation, as well as their compliance and response to treatment.

Table 20-2 presents the DSM-IV-TR classification system (based on severity) for mental retardation along with estimates of their approximate prevalence.1 These categories do not reflect functional capabilities per se but should be used by the psychiatrist to get a better understanding of how an individual with such an IQ might be expected to present. The overwhelming majority of individuals with mental retardation fall in the mild to moderate category and are the ones most likely to present for community treatment. Individuals with severe to profound mental retardation are more commonly seen in institutional settings, but this can vary greatly from state to state and from region to region.

Table 20-2 Classification of Severity and Approximate Percentages of Mental Retardation in the Population

| Severity | IQ Range | Percentage of Population |

|---|---|---|

| Mild | 50-55 to 70 | 85 |

| Moderate | 35-40 to 50-55 | 10 |

| Severe | 20-25 to 35-40 | 3-4 |

| Profound | Below 20-25 | 1-2 |

Diagnosis

Familiarity with the standard evaluation of mental retardation is helpful to ensure that a patient with a diagnosis of mental retardation has had a through workup and that the diagnosis is accurate.13,14 In addition, certain syndromes and causes of mental retardation are associated with specific behaviors and psychiatric disorders. Thus, it is often helpful to identify these syndromes to aid in the clinical assessment.15

Although there are no laboratory findings that specifically identify mental retardation, there are multiple causes (including metabolic disturbances, toxin exposure, and chromosomal abnormalities) of mental retardation that can be identified via laboratory analysis.15 If a patient with mental retardation has never had a chromosomal analysis, a genetics consultation is recommended. This can sometimes shed light on a previously unidentified syndrome in an adult patient that may then help to make a psychiatric diagnosis or to inform family members of potential medical issues that require monitoring. In addition, a genetics consultation can educate the psychiatristabout dysmorphic features in a patient with a given syndrome. The psychiatrist can then use this information to help identify other patients in the future. Figure 20-1 through Figure 20-6 identify dysmorphic features seen in individuals with various syndromes associated with mental retardation.

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

OVERVIEW

Once the psychiatrist has determined that the diagnosis of mental retardation is accurate, that the workup is complete, and that there are no underlying medical or neurological issues affecting behavior, the patient should be assessed for behavioral or psychiatric disorders that may impact adaptive function.16,17 The psychiatrist should begin with a basic understanding of the patient’s developmental level and how this might affect the expression of psychiatric symptoms. As previously stated, the full range of psychopathology is seen in the mentally-retarded population. In addition there are unique behavioral disorders and pathobehavioral syndromes or behavioral phenotypes to consider.

The next step in the assessment of an individual with mental retardation involves a functional behavioral analysis that seeks to determine if the patient’s behavior is “functional” in nature, that is, whether the behavior serves a purpose for the individual (not always with direct conscious awareness), such that it is reinforced and continues.16,17 Examples include self-injury for the communication of pain, discomfort, or dislike; agitation or loud vocalizations to gain attention of staff or parents; or aggression to “get out of doing something” (i.e., escape-avoidance behavior). In each case, the observed behavior is not part of an underlying psychiatric disorder per se, yet it serves a purpose. If so-called functional behavior is suspected, a referral to a behavior analyst should then be initiated before further assessment or treatment.

Behavioral Disorders

Aggressive behavior is the main reason for psychiatric consultation and for institutionalization in the mentally-retarded population. Once a thorough assessment has been completed and no clear etiology found, the problem falls into the realm of an impulse-control disorder. Behavioral treatment is usually the first-line treatment. Subsequent psychopharmacological interventions can be attempted if behavioral treatment proves inadequate. Typically, agents used to treat impulsive aggression are tried; these include alpha-agonists, beta-blockers, lithium, other mood stabilizers/antiepileptic drugs, and antipsychotics.18,19

Self-injurious behavior (SIB) refers to behavior that potentially or actually causes physical damage to an individual’s body. This should not be confused with self-mutilation or para-suicidal behavior that is more obviously volitional and seen in individuals with personality disorders. SIB in the mentally-retarded population usually manifests as idiosyncratic, repetitive acts that occur in a stereotypic form. Behavioral therapy is the first-line treatment. Subsequent treatment includes use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (due to the apparent compulsive nature of the behavior) and neuroleptics in severe and refractory cases.18,19

Stereotypy, given the repetitive nature of the behavior, is sometimes related to SIB. Stereotypies are invariant, pathological motor behaviors or action sequences without obvious reinforcement. They often cause no real harm or dysfunction, but may be upsetting to caregivers or staff who may believe that they interfere with the patient’s quality of life. These behaviors are often seen in institutionalized adults with severe to profound mental retardation; however, they can also be seen as a normal variant in children without cognitive delay. These behaviors are often seen in circumstances of extreme stimulation or deprivation. First-line treatment for these stereotypies is behavioral. It is up to the patient or to the patient’s guardian (in conjunction with the psychiatrist) to determine whether to engage in more aggressive medication treatments that are based on the level of dysfunction these behaviors represent. SSRIs should be considered for initial psychopharmacological treatment because of the compulsive nature of these behaviors.10,11,18,19

Traditional Psychiatric Disorders

Anxiety disorders are common in the mentally retarded, and observable signs and symptoms of anxiety are often more helpful than are self-reports of anxiety. Those anxiety disorders that manifest with more somatically-based symptoms are easier to diagnose, as staff can measure symptoms (such as elevated pulse and blood pressure in panic disorder), whereas chronic worry (in generalized anxiety disorder [GAD]) may be harder to measure. Anxiety rating scales, both verbal and nonverbal, can be very useful.

Anxiety issues around transitions (daily transitions and around life stages) are commonly seen. The possibility of trauma and related posttraumatic stress must always be considered, especially if there is an acute change from baseline. The mentally retarded are a vulnerable population that is frequently exploited. At times, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is difficult to distinguish from stereotypy. This is due to the difficulty eliciting self-reported ego-dystonic feelings around the behavior in question. Often, however, if a response-blocking intervention is attempted, individuals with OCD may have increased anxiety, whereas individuals with stereotypy do not. Treatment options for anxiety disorders include relaxation training and other behavioral therapy techniques. Sensory integration interventions can be tried under the guidance of a qualified occupational therapist. A variety of approved psychotropics (including benzodiazepines) should be considered for the relief of anxiety.10,18,19

Syndrome-Associated Disorders

Individuals with Down syndrome (see Figure 20-1) or trisomy 21 have the classic physical features of round face, a flat nasal bridge, and short stature. Their level of mental retardation is variable.20 Depression is a common psychiatric co-morbidity, but perhaps better known is dementia of the Alzheimer’s type.15 However, symptoms of dementia often occur in the patient’s forties and fifties. Symptomatic treatment for the accompanying behaviors can be helpful, but it is still unclear what role treatment of the underlying dementia plays (e.g., anticholinesterase inhibitors or NMDA receptor antagonists). Standard treatments often seek to preserve autonomous and independent function and to delay institutional placement, issues that may already have been addressed due to the patient’s baseline cognitive function. Thus, the risk/benefit ratio for the treatment of the underlying dementia and the clarity of outcome measures may be less well defined for this population and should be discussed in detail with a guardian or family member.

Individuals with fragile X syndrome (see Figure 20-2) have an abnormality on the long arm of the X chromosome at the q27 site (FMR1 gene). Common physical features include an elongated face, prominent ears, and macro-orchidism. The majority of affected individuals are males, but females can also be affected. Their level of mental retardation varies.20 Of note, a percentage of female carriers can also display cognitive disabilities. The most prominent co-morbidities are attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and social anxiety disorder.15 In addition, autistic features have been noted in a large percentage of individuals with fragile X syndrome, but autism and fragile X syndrome are not co-occurring conditions.

Individuals with the Prader-Willi syndrome (see Figure 20-4) typically have short stature, hypogonadism, and marked obesity with hyperphagia. In approximately 70% of cases the syndrome results from a chromosome 15 deletion. The level of mental retardation can vary.20 Although the patient can have stubbornness, cognitive rigidity, and rage, the most common psychiatric co-morbidity is OCD.15 The level of insight with regard to the excessiveness of the obsessions or compulsions can vary, but there is often an ego-dystonic aspect and verbalizations for help.

Williams syndrome (see Figure 20-5) results from a deletion on chromosome 7. These individuals have elfin-like faces and a classic starburst (or stellate) pattern of the iris. They can have supravalvular aortic stenosis, as well as renal artery stenosis and hypertension. Their level of mental retardation varies.20 Behaviorally, they can be loquacious communicators, a phenomenon referred to as “cocktail party speech” (often attributable to a higher verbal than performance IQ). This can be deceiving, as individuals with greater verbal skills can appear to have higher functioning than they actually have. Common co-morbidities include anxiety disorders (such as GAD) and depression.15

Twenty-two q-eleven (22q11) deletion syndrome (including velo-cardio-facial syndrome and DeGeorge syndrome) is an autosomal dominant condition manifested by a medical history of midline malformations (such as cleft palate, velopharyngeal insufficiency, and cardiac malformations [such as a ventricular septal defect]) (Figure 20-6). Patients have small stature, a prominent tubular nose with bulbous tip, and a squared nasal root. There is often a history of speech delay with hypernasal speech. Their level of cognitive impairment varies from learning disabilities and mild intellectual impairment to more severe levels of mental retardation.20 The reason 22q11 deletion syndrome is of interest to psychiatrists is its high co-morbidity with psychosis (prevalence rates of up to 30% have been reported).21 It has been proposed as a genetic model for understanding schizophrenia.21

1 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 2000.

2 King BH, Hodapp RM, Dykens EM, Mental retardation Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, editors. Kaplan and Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, ed 7, vol 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000.

3 Curry C, Stevenson R, Aughton D, et al. Evaluation of mental retardation: recommendations of a consensus conference: American College of Medical Genetics. Am J Med Genet. 1997;72:468-477.

4 King BH, State MW, Shah B, et al. Mental retardation: a review of the past 10 years. Part I. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:1656-1663.

5 Nurnberger J, Berrettini W. Psychiatric genetics. In: Ebert M, Loosen P, Nurcombe B, editors. Current diagnosis and treatment in psychiatry. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000.

6 Volkmar FR, Dykens E. Mental retardation. In Lewis M, editor: Child and adolescent psychiatry: a comprehensive textbook, ed 3, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

7 Bouras N, editor. Psychiatric and behavioural disorders in developmental disabilities and mental retardation. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

8 Gualtieri CT. Neuropsychiatry and behavioral pharmacology. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1990.

9 Madrid AL, State MW, King BW. Pharmacologic management of psychiatric and behavioral symptoms in mental retardation. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2000;9(1):225-243.

10 Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with mental retardation and co-morbid mental disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(12, suppl):5s-31s.

11 State MW, King BH, Dykens E. Mental retardation: a review of the past 10 years. Part II. J Am Acad ChildAdolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:1664-1671.

12 Szymanski LS, Wilska M, Mental retardation Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman JA, editors. Psychiatry, ed 2, vol 1. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons, 2003.

13 Jacobson JW, Mulick JA, editors. Manual of diagnosis and professional practice in mental retardation. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1996.

14 Luckasson R, Borthwick-Duffy S, Buntinx WH, et al. Mental retardation: definition, classification, and systems of supports. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation, 2002.

15 Volkmar FR, editor Mental retardation Child Adolesc Psychiatry Clin North Am;5, 4, 1996.

16 Paclawskyj TR, Kurtz PF, O’Connor JT. Functional assessment of problem behaviors in adults with mental retardation. Behavior Modification. 2004;28(5):649-667.

17 Wieseler NA, Hanson RH, editors. Challenging behavior of persons with mental health disorders and severe developmental disabilities. Washington DC: American Association on Mental Retardation, 1999.

18 Matlon JL, Bamburg JW, Mayville EA, et al. Psychopharmacology and mental retardation: a 10-year review (1990-1999). Res Develop Disabilities. 2000;21(4):263-296.

19 Reiss S, Aman MG, editors. Psychotropic medication and developmental disabilities: the international consensus handbook. Ohio State University Nisonger Center, 1998.

20 Jones KL. Smith’s recognizable patterns of human malformation, ed 5. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1997.

21 Williams NM, Owen MJ. Genetic abnormalities of chromosome 22 and the development of psychosis. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2004;4:176-182.