CHAPTER 2. Ethics, bioethics and nursing ethics: some working definitions

L earning objectives

▪ Define the following concepts:

• ethics

• morality

• bioethics

• nursing ethics.

▪ Discuss why it is important to have a correct understanding of the terms commonly used in discussions and debates about ethics and ethical issues in nursing and health care.

▪ Discuss why each of the following processes cannot be relied upon to guide sound and just ethical conduct in nursing and health care contexts:

• law

• codes of ethics

• hospital or professional etiquette

• hospital or institutional policy

• public opinion or the view of the majority

• following the orders of a supervisor or manager.

K eywords

I ntroduction

Understanding the basis of ethical professional conduct in nursing requires nurses to have at least a working knowledge and understanding of the language, concepts and theories of ethics. One reason for this, as explained by the English philosopher, Richard Hare (1964: 1–2), is that:

in a world in which the problems of conduct become every day more complex and tormenting, there is a great need for an understanding of the language in which these problems are posed and answered. For confusion about our moral language leads, not merely to theoretical muddles, but to needless practical perplexities.

At first glance it might seem cumbersome spending time on clarifying and developing an understanding of the language, concepts and underpinning theories used in discussions and debates on ethics. Upon closer examination, however, it soon becomes clear that such an undertaking is crucial if nurses and their associates are to engage in a meaningful inquiry into what ethics is, what constitutes ‘nursing ethics’ and how, if at all, nursing ethics differs from other fields of ethics, what it means to be an ‘ethical practitioner’, why nurses have an obligation to practise their profession in an ethical manner, and how to be an ethical professional. Furthermore, and not least, how best to proceed with the difficult task of identifying and resolving the many moral problems that nurses (like others in the health care team) will inevitably encounter during the course of their everyday practice.

T he importance of understanding ethics terms and concepts

The terms ‘ethics’, ‘morality’, ‘rights’, ‘duties’, ‘obligations’, ‘moral principles’, ‘moral rules’, ‘morally right’, ‘morally wrong’, ‘moral theory’, to name some, are all commonly used in discussions about ethics. Nurses, like others, may use some of these terms when discussing life events and practice situations that are perceived as having a moral/ethical dimension. These terms are not always used correctly, however, with the unfortunate consequence of communication and discussions about ethical issues sometimes becoming distorted and, as a consequence, giving rise to problems and perplexities that did not exist previously or which could otherwise have been avoided had they been dealt with more competently.

One notable example of the incorrect use of ethical terms can be found in the tendency by some nurses (scholars included) to treat the terms ‘rights’ and ‘responsibilities’ or ‘duties’ as being synonymous, and thus able to be used interchangeably. An example of this is found in the International Council of Nurses (ICN) position statement on the ‘rights and duties of nurses’, adopted at the ICN’s Council of National Representatives meeting in Brazil in June 1983: ‘Nurses have a right to practise within the code of ethics and nursing legislation’ (Keireini 1983: 4, emphasis added). When the nature of rights and duties is examined later, it will become clear that the term ‘right’ in this example should, in fact, read ‘duty’. The implications of confusing the meanings of the terms ‘rights’ and ‘duties’ and treating these two terms as being synonymous will be explored more fully in the chapters to follow.

Another common mistake is the tendency by some nurses to draw a distinction between the terms ‘ethics’ and ‘morality’. They draw a distinction on the grounds that, in their view, morality involves more a personal or private set of values (i.e. ‘personal morality’) whereas ethics is more concerned with a formalised, public and universal set of values (i.e. ‘professional ethics’) (see, for example, Thompson et al 2000; Leininger 1990a). As will be shown shortly, there is, in fact, no philosophically significant difference between the terms ‘ethics’ and ‘morality’ and to distinguish between them is both unnecessary and confusing.

T he need for a critical inquiry into ethical professional practice

It is acknowledged that most people brought up in a common cultural context share what Beauchamp and Childress (2001: 3) call a ‘common morality’; that is, a set of core norms and dimensions of morality that most people accept as being relevant and important (e.g. respect the rights of others, do not harm or kill innocent people, it is wrong to steal, it is wrong to break promises, and so forth) and about which philosophical debate ‘would be a waste of time’ (Beauchamp & Childress 2001: 3). It would be a mistake, however, to assume or to accept that ‘common morality’ or ‘commonsense morality’ is in and by itself sufficient to enable nurses to deal with the many complex and complicated ethical issues that they will encounter in their practice. As examples to be presented in the following chapters will show, while our ‘ordinary moral apparatus’ may motivate and guide us to behave ethically as people, it is often quite inadequate to the task of guiding us to deal safely and effectively with the many complex ethical issues that rise in nursing and health care contexts. A much more sophisticated moral competency and capability is required than that otherwise provided by a ‘commonsense’ morality.

If nurses are serious about ethics and about conducting themselves ethically in the various positions, levels, and contexts in which they work, then they must engage in a critical inquiry about what ethics is and how it can best be applied in the ‘real world’ of professional nursing practice. It cannot be assumed that just because we know of and use certain ethical terms in our conversations that we know what they mean or that we are using them correctly. As Warnock warns in his classic work Contemporary moral philosophy (1967: 75):

When we talk about ‘morals’ we do not all know what we mean; what moral problems, moral principles, moral judgments are is not a matter so clear that it can be passed over as simple datum. We must discover when we would say, and when we would not, that an issue is a moral issue, and why; and if, as is more than likely, disagreements should come to light even at this stage, we could at least discriminate and investigate what reasonably tenable alternative positions there may be.

U nderstanding moral language

When discussing and advancing debates on ethical issues in nursing and health care it is vital that all parties involved have a shared working knowledge and understanding of the meanings of terms and concepts that are fundamental to the issues being considered. This imperative is captured by the philosophical adage ‘there must first be agreement before there can be disagreement’. The reasoning behind this imperative is that unless there is a shared understanding of core terms and concepts it will be extremely difficult if not impossible to develop insight and understanding of the issues at stake and address if not resolve the disagreements and conflicts that may have arisen in relation to them. For example, if two dissenting parties do not share a common understanding about the nature and content of human rights (what these entail, the moral authority they have, what entities can validly claim human rights, and so forth) they cannot even begin to debate the conditions under which human rights ought to be respected and when they might justifiably be overridden, and to take action accordingly. Similarly, if two dissenting parties do not share a common conception of what nursing ethics is, then they cannot meaningfully debate whether or not nursing ethics ought to be recognised as a distinctive field of inquiry and practice in its own right, or whether nurses are obliged to uphold the standards of ethical conduct developed as a result of focused nursing ethics inquiry.

In developing a shared understanding of core terms and concepts used in discussions and debates on ethical issues it is important for nurses to be aware that, contrary to expectations, many of the terms commonly used in ethical debates are themselves ‘ethically loaded’ and thus, paradoxically, at risk of distorting if not corrupting the debates. The notion of ‘quality of life’ is a good example. Many writers on bioethics assume that when a life ceases to be ‘independent’ it has diminished worth. In instances where quality of life has been a criterion for decision-making at the end stage of life, euthanasia might be considered a right and proper course of action to take. Here the ethically loaded notion of ‘dependence’ imparts a sense of the permissibility of the euthanasia option and limits thought of, say, pursuing a rehabilitation option. It also overrides thought of the possibility that for some people dependence may be quite irrelevant to the notion of a worthwhile life. Kanitsaki (1993, 1994), for example, has shown that in some traditional cultural groups, familial and friendly relationships are characteristically collective and interdependent, and that any thought of individual independence is quite irrelevant to the assessment of ‘a life worth living’.

Poorly or inappropriately defined ethical terms and concepts can seriously impinge upon and limit people’s moral imagination, and the moral options and choices that might otherwise be identified, considered and chosen in the face of moral disagreement, conflict and adversity.

W hat is ethics?

It is appropriate to begin the task of defining commonly used ethical terms and concepts by first examining the terms ‘ethics’ and ‘morality’, and clarifying from the outset there is no philosophically significant difference between the terms ‘ethics’ and ‘morality’. If a distinction is to be drawn between these two terms it is one that is based on etymological grounds (the study of the origin of the words), with ‘ethics’ coming from the ancient Greek ethikos (originally meaning ‘pertaining to custom or habit’), and ‘morality’ coming from the Latin moralitas (also originally meaning ‘custom’ or ‘habit’). This means that the terms may be used interchangeably, as they are in the philosophic literature and in this work. With respect to deciding which terms should be used in ethical discourse (i.e. whether to use the term ‘ethics’ or the term ‘morality’), this is very much a matter of personal preference rather than of philosophical debate, noting, however, that the terms ethics and morality have come to refer to something far more sophisticated than ‘custom’ or ‘habit’, as will soon be shown.

Having clarified that there is no philosophically significant difference between the terms ‘ethics’ and ‘morality’, it now remains the task here to define what ‘ethics’ is.

For the purposes of this discussion ethics is defined as a generic term that is used for referring to various ways of thinking about, understanding and examining how best to live a ‘moral life’ (Beauchamp & Childress 2001). More specifically, ethics involves a critically reflective activity that is concerned with a systematic examination of living and behaving morally and ‘is designed to illuminate what we ought to do by asking us to consider and reconsider our ordinary actions, judgments and justifications’ (Beauchamp & Childress 1983: xii). For example, a nurse may make an ‘ordinary’ moral judgment that abortion is wrong and conscientiously object to assisting with an abortion procedure. Whether her conscientious objection ought to be respected, however, requires a critical examination of the bases upon which the nurse has made that judgment and a consideration of the justifications (moral reasons) she has put forward to support the position she has taken.

Ethics, as it is referred to and used today, can be traced back to the influential works of the Ancient Greek philosophers Socrates (born 469 BC), Plato (born 428 BC) and Aristotle (born 384 BC). The works of these ancient Greek philosophers were especially influential in seeing ethics established as a branch of philosophical inquiry which sought dispassionate and ‘rational’ clarification and justification of the basic assumptions and beliefs that people hold about what is to be considered morally acceptable and morally unacceptable behaviour. Ethics thus evolved as a mode of philosophical inquiry (known as moral philosophy) that asked people to question why they considered a particular act right or wrong, what the reasons (justifications) were for their judgments, and whether their judgments were correct. This view of ethics remains an influential one and, although the subject of increasing controversy over the past two decades, retains considerable currency in the mainstream ethics literature.

It is important to clarify that ethics has three distinct ‘sub-fields’, namely: descriptive ethics, metaethics and normative ethics. Descriptive ethics is concerned with the empirical investigation and description of people’s moral values and beliefs (i.e. values and beliefs concerning what constitutes ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ or ‘good’ and ‘bad’ conduct). Metaethics, in contrast, is concerned with analysing the nature, logical form, language and methods of reasoning in ethics (e.g. it gives consideration to meanings of ethical terms such as ‘rights’, ‘duties’, and so on). Normative ethics, in turn, is concerned with establishing standards of correctness by identifying and prescribing certain rules and principles of conduct and developing theories to justify the norms established. Unlike descriptive ethics and metaethics, normative ethics is evaluative and prescriptive (hortatory) in nature. In the case of the latter, ethics inquiry is not so much concerned with how the world is, but with how it ought to be. In other words, it is not concerned with merely describing the world (although, of course, a description of the world is necessary as a starting point for an evaluative inquiry), but rather in prescribing how it should be and providing sound justification for this prescription. Just what is to count as a ‘sound justification’, however, is an open question and one that will be considered in the following chapter. In this book, all three sub-fields are drawn upon in varying degrees to advance knowledge and understanding of ethical issues in nursing and health care.

W hat is bioethics?

Bioethics is a relatively new field of inquiry and can be defined as ‘the systematic study of the moral dimensions — including moral vision, decisions, conduct and policies — of the life sciences and health care, employing a variety of ethical methodologies in an interdisciplinary setting’ (Reich 1995a: xxi). The term ‘bioethics’ (from the Greek bios meaning ‘life’, and ethikos, ithiki meaning ‘ethics’) is a neologism which first found its way into public usage in 1970–71 in the United States of America (Reich 1994; see also Jecker et al 2007). Although originally the subject of only cautious acceptance by a few influential North American academics, the new term quickly ‘symbolised and influenced the rise and shaping of the field itself’ (Reich 1994: 320). Significantly, within 3 years of its emergence, the new term was accepted and used widely at a public level (Reich 1994: 328). Interestingly, it is believed that the term ‘bioethics’ caught on because it was ‘simple’ and because it was amenable to exploitation by the media which had placed a great premium ‘on having a simple term that could readily be used for public consumption’ (Reich 1994: 331).

It is worth noting that initially the term ‘bioethics’ was used in two different ways, reflecting both the concerns and ambitions of two respective academics who, it is suggested, quite possibly created the word independently of each other. The first (and later marginalised) sense in which the word was used had an ‘environmental and evolutionary significance’ (Reich 1994: 320). Specifically, it was intended to advocate attention to ‘the problem of survival: the questionable survival of the human species and the even more questionable survival of nations and cultures’ (Potter 1971 — cited by Reich 1994: 321). In short, it advocated long-range environmental concerns (Reich 1995b: 20). Reich (1994: 321–2) explains that the key objective in creating this term was:

to identify and promote an optimum changing environment, and an optimum human adaptation within that environment, so as to sustain and improve the civilised world.

The other competing sense in which the word ‘bioethics’ was used referred more narrowly to the ethics of medicine and biomedical research. The primary focus of this approach was (Reich 1995b: 20):

1. the rights and duties of patients and health care professionals

2. the rights and duties of research subjects and researchers

3. the formulation of public policy guidelines for clinical care and biomedical research.

Significantly, it was this latter sense which ‘came to dominate the emerging field of bioethics in academic circles and in the mind of the public’ — and which remains dominant today (Reich 1994: 320). There are a number of complex reasons for this, not least, the climate at the time which saw the rise of the civil rights movement (including women’s rights and the legal right to abortion which helped to keep bioethical issues ‘before the public’). Given the significant shift in social and moral values that was occurring at the time, however, it is perhaps not surprising that this essentially medical/biomedical sense of bioethics prevailed (Jonsen 1993; Singer 1994). For instance, it is now almost certain that the ideas behind the development of the field of bioethics in its medical/biomedical sense had been simmering for almost a decade before the field was eventually named (Jonsen 1993: S3; see also Jecker et al 2007). Notable among the events inspiring the development of the field were: the dialysis events of the early 1960s, the publication in 1966 of Henry Beecher’s legendary and confronting article on the unethical design and conduct of 22 medical research projects, the heart transplant movement, and later the now famous 1975 Karen Ann Quinlan case (Beecher 1966; Jonsen 1993; Singer 1994).

Today, the dominant concerns of mainstream Western bioethics are still essentially medically orientated, with the most sustained attention (and, it should be added, the most institutional support) being given to examining the ethical and legal dimensions of the ‘big’ issues of bioethics, such as abortion, euthanasia, organ transplantation (and the associated issue of brain-death criteria), reproductive technology (e.g. in vitro fertilisation [IVF], genetic engineering, human cloning, and so forth), ethics committees, informed consent, confidentiality, the economic rationalisation of health care, and research ethics (particularly in regard to randomised clinical trials and experimental surgery). Not only has mainstream bioethics come to refer to and represent these issues, but, rightly or wrongly, has given legitimacy to them as the most pressing bioethical concerns of contemporary health care across the globe.

It is alleged that Potter (one of the authors of the term ‘bioethics’) was himself very frustrated with this narrow conception of bioethics and is reported as responding that ‘my own view of bioethics calls for a much broader vision’ (Reich 1995b: 20). Indeed, Potter feared (prophetically as it turned out) that ‘the Georgetown approach would simply reaffirm medical professional inclination to think of issues in terms of therapy versus prevention’ (Reich 1995b: pp 20–1). Whereas Potter viewed bioethics as a ‘new discipline’ (of science and philosophy) emphasising a search for wisdom, the Georgetown group saw bioethics as an old discipline (applied ethics) to resolve concrete moral problems; that is, ‘ordinary ethics applied in the bio-realm’ (p 21).

It has been claimed that ‘bioethics is a native-grown American product’ reflecting distinctively American concerns and offering distinctively American solutions and resolutions to the bioethical problems identified (Jonsen 1993, S3–4). Whatever the merits of this claim, there is little doubt that bioethics in its medical/biomedical sense has become an international movement. This movement (propelled along by a variety of processes) has witnessed a number of spectacular achievements, including:

▪ the development of an awesome international body of literature on the subject of bioethics (including the publication in 1978 of the first Encyclopedia of Bioethics (revised in 1995, 2004) and, in the 1990s, the development and dissemination of the CD-ROM Bioethics Line)

▪ the global establishment of research centres devoted specifically to investigating ethical issues in health care and related matters

▪ the emergence in the 1990s of a new profession of hospital ethicists/consultant ethicists

▪ the establishment of prestigious university chairs in applied ethics

▪ the rise of a commercially viable and even lucrative bioethics education industry, and, not least

▪ the stimulation of public and political debate on ‘life and death’ matters in health care which, in many instances, has had a positive effect on influencing long overdue social policy and law reform in regard to these matters.

The medical/biomedical senses of the term ‘bioethics’ have indeed dominated intellectual and political thought over the past three to four decades. Nevertheless, there are signs that this dominance has been called into question and is slowly changing as more attention is given to such issues as environmental ethics, climate change, and the relationship between health and human rights. (See, for example, the introductions to the second edition [edited by Reich 1995a] and the third edition [edited by Post 2004] of the Encyclopedia of Bioethics; the landmark work of Jonathan Mann and associates on the fundamental relationship between health and human rights [Mann 1996, 1997; Mann et al 1999; Anand et al 2004; Gruskin et al 2005]; and the rise of the ‘new’ public health ethics [see, for example, Beauchamp & Steinbock 1999; Beyrer & Pizer 2007; Daniels 2006; Powers & Faden 2006].) At present, there is considerable room to speculate that in the not too distant future the term ‘bioethics’ might once again hold an environmental, evolutionary and humanitarian significance, and have a much broader focus than it has up until now.

W hat is nursing ethics?

Nursing ethics can be defined broadly as the examination of all kinds of ethical and bioethical issues from the perspective of nursing theory and practice which, in turn, rest on the agreed core concepts of nursing, namely: person, culture, care, health, healing, environment and nursing itself (or, more to the point, its ultimate purpose) — all of which have been comprehensively articulated in the nursing literature (too vast to list here). In this regard, then, contrary to popular belief, nursing ethics is not synonymous with (and indeed is much greater than) an ethic of care, although an ethic of care has an important place in the overall moral scheme of nursing and nursing ethics. Unlike other approaches to ethics, nursing ethics recognises the ‘distinctive voices’ that are nurses, and emphasises the importance of collecting and recording nursing narratives and ‘stories from the field’ (Benner 1991, 1994; Bishop & Scudder 1990; Parker 1990). Collecting and collating stories from the field are regarded as important since issues invariably emerge from these stories that extend far beyond the ‘paramount’ issues otherwise espoused by mainstream bioethics. Analyses of these stories tend to reveal not only a range of issues that are nurses’ ‘own’, as it were, but a whole different configuration of language, concepts and metaphors for expressing them. As well, these stories often reveal issues otherwise overlooked in mainstream bioethics discourses. Given this, nursing ethics can also be described as methodologically and substantively, inquiry from the point of view of nurses’ experiences, with nurses’ experiences being taken as a more reliable starting point than other locations from which to advance a rich, meaningful and reliable system and practice of nursing ethics.

Like other approaches to ethics, however, nursing ethics recognises the importance of providing practical guidance on how to decide and act morally. Drawing on a variety of ethical theoretical considerations (what Beauchamp & Childress [2001: 400] call a ‘coherentist’ approach, and Benjamin [2001] calls a ‘pragmatic reflective equilibrium’ approach), nursing ethics at its most basic could thus also be described as a practice discipline which aims to provide guidance to nurses on how to decide and act morally in the contexts in which they work.

The project of nursing ethics has many aspects to its nature and approach. Among other things, it involves nurses engaging in ‘a positive project of constructing and developing alternative models, methods, procedures [and] discourses’ of nursing and health care ethics that are more responsive to the lived realities and experiences of nurses and the people for whose care they share responsibility (adapted from Gross 1986: 195). In completing this project, nursing ethics has had — and continues to have — the positive consequence of allowing other ‘weaker’ viewpoints (including those of patients and nurses themselves) to emerge and be heard. In this respect, nursing ethics is also intensely political — although, it should be added, no more political than other role-differentiated ethics.

As in the case of moral philosophy, nursing ethics inquiry can be pursued by focusing on one or all of the following:

▪ descriptive nursing ethics (describing the moral values and beliefs that nurses hold and the various moral practices in which nurses engage across and within different contexts)

▪ meta (nursing) ethics (undertaking a critical examination of the nature, logical form, language and methods of reasoning in nursing ethics)

It is important to remember (as discussed in the 3rd edition of this work [Johnstone 1999a]) that nursing ethics has not always enjoyed the status that it has today. Its development, legitimation and recognition as a distinctive field of inquiry is testimony to the reality that nursing ethics is both necessary and inevitable. It is necessary because ‘a profession without its own distinctive moral convictions has nothing to profess’ and will be left vulnerable to the corrupting influences of whatever forces are most powerful (be they religious, legal, social, political or other in nature) (Churchill 1989: 30). Furthermore, as Churchill (1989: 31) writes, ‘Professionals without an ethic are merely technicians, who know how to perform work, but who have no capacity to say why their work has any larger meaning.’ Without meaning, there is little or no motivation to perform ‘well’.

In regard to the inevitability of nursing ethics, as Churchill (1989: 31) points out, the ‘practice of a profession makes those who exercise it privy to a set of experiences that those who do not practice lack’. By this view, those who practise nursing are privy to a set of experiences (moral experiences included) that others who do not practise nursing lack. So long as nurses interact with and enter into professional caring relationships with other people, they will not be able to avoid or sidestep the ‘distinctively nursing’ experience of deciding and acting morally while in these relationships. It is in this respect, then, that nursing ethics can be said to be inevitable.

W hat ethics is not

To further our understanding on what ethics (and its counterparts bioethics and nursing ethics) is, it would be useful to also give some attention to what ethics is not. For instance, ethics is not the same as law or a code of ethics. Neither is ethics something that can be determined by public opinion, or following the orders of a supervisor or manager. Failing to distinguish ethics from these kinds of things could result in otherwise avoidable harmful consequences to people in health care domains.

L aw

Ethics and law overlap in significant ways, but they are nevertheless quite distinct from one another. This distinction becomes particularly clear in instances where what the law may require in a given situation, ethics might equally reject, and vice versa. Consider, for example, the issue of active voluntary euthanasia and the plight of patients suffering intractable, intolerable and irremediable pain who request euthanasia as a ‘treatment’ option (Lanham 1993). Current Australian legal law prohibits voluntary active euthanasia. As the law stands, it is quite clear that any nurse or doctor who administers a lethal injection to a patient with the sole intention of bringing about that patient’s death would probably be charged with murder. The fact that such an act was demonstrably in accordance with the patient’s autonomous wishes would not be a legitimate defence. Regardless of the benevolence and voluntariness of an act of euthanasia, it would still be deemed by law as illegal, and thereby legally wrong. This legal wrongness, however, is not necessarily synonymous with moral wrongness. Consider the following.

Ethics essentially requires that people be respected as self-determining choosers, and further that the considered preferences of autonomous persons be maximised. This requirement holds even in instances where a person’s individual preferences might be considered mistaken or foolish by others. Ethics also requires that otherwise avoidable harm (such as the needless suffering of intractable and intolerable pain) should be prevented where this can be done without sacrificing other important moral interests. Returning to our euthanasia example, it soon becomes clear that an application of ethics (or, more particularly, the principles of bioethics) might, in this instance, permit the administration of a lethal injection to a suffering patient who has autonomously requested it. Not only might ethics permit such an act; it might actually require that it be done. Where sound moral justifications for the act can be shown, then the act of euthanasia in question could be deemed as having accorded with the principle of ethics and thereby as being morally right.

Other compelling examples illuminating the difference between law and morality can be found by considering the laws enforced during wartime (such as those upheld by the Nazi regime), and the laws used to enforce apartheid (such as those upheld in early North America, and, until recently, in South Africa). The legal laws of the Nazis and of the apartheid-supporting regimes, although evil, still stand as constituting valid legal law (Hart 1958). We would presumably want to resist condoning the morality of these laws, however.

Law and ethics are quite separate action-guiding systems, and care must be taken to distinguish between them. Making this distinction may not only help to prevent moral errors, but may also enforce moral and intellectual honesty about the undesirability of morally bad (evil) law (Hart 1958). Further, if we do not make this distinction we will not have an independent value system from which to judge the moral acceptability or unacceptability of valid legal law. For instance, if morality were not distinct from legal law, we could not judge certain laws (e.g. Nazi laws) to be morally bad and wrong.

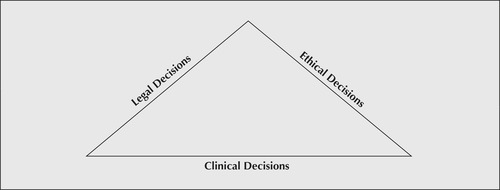

The question remains, however, of how the distinction between law and ethics can be made, and, equally important, what the essential differences are between a legal decision and a moral/ethical decision, and, indeed, a clinical decision.

A very traditional view of law is that it is the command or order of a sovereign (for example, a government) backed by a threat or sanction (e.g. punishment) (Hart 1961). For instance, governments around the world have formulated laws which command their citizens to pay taxes; if the citizens in question fail to pay their taxes, they can expect to be punished in some way, such as by being fined or even sent to prison. The mere fact that they have not complied with the command — in essence, have broken the law — would probably be deemed sufficient justification for a sanction or punishment to be directed against them. Although this view of law does not capture its more political nature (see, e.g. Fineman & Thomadsen 1991; Johnstone 1994; Kairys 1982), it is nevertheless sufficient for the purposes of this discussion in regard to distinguishing between law and ethics.

Accepting the above view of law, there is a fundamental sense in which the concept ‘legal decision’ as it is used by nurses probably refers to a type of decision that is made on the basis of what is required or prohibited by law — together with a desire to avoid a legal sanction or punishment for non-compliance. In this respect, the notion ‘legal decision’ is probably more aptly described as a ‘legally defensive’ decision. Consider the following example. A nurse who regards voluntary euthanasia as morally justified in cases of intolerable, intractable and irremediable suffering may nevertheless decline a patient’s considered request for assistance to die in order to avoid any legal risk of receiving the penalty that would almost certainly be applied for murder should her actions be discovered. In this instance, the nurse’s decision not to comply with the patient’s request could be described as a ‘legal decision’ rather than a moral or clinical decision, and also as being ‘legally defensive’. This is because her decision was influenced predominantly by considering the legal consequences of complying with the patient’s request, rather than the moral or clinical consequences of doing so.

The question remains, however, of how a legal decision differs from an ethical decision. As is discussed more fully in the following chapter, ethics can be defined as a system of overriding rules and principles which function by specifying that certain behaviours are either required, prohibited or permitted. These principles are chosen autonomously on the basis of critical reflection, and are backed by autonomous moral reason (generally recognised in moral philosophy as the central organising principle of morality) and/or by feelings of guilt, shame, moral remorse and the like which operate as kinds of moral sanctions. For example, we may choose autonomously to follow a moral principle which demands truth telling; if we fail to tell the truth in a given situation, we may then reason the act to be wrong and/or experience feelings of guilt, shame or moral remorse accordingly. Unlike what happens in instances involving a breach of legal law, however, we are not generally ‘punished’ for lying — for example, by being fined or sent to prison — unless, of course, our lying entails an outright act of perjury in a court of law.

Accepting this view of ethics, it is probably correct to say that the concept ‘ethical decision’, as it is used in health care contexts, refers to a type of decision which is guided by certain moral principles of conduct or other moral considerations (rather than by punitive legal laws) and a desire to achieve a given moral end. Thus, a doctor or a nurse tempted to tell a lie to either a colleague or a patient may choose instead to tell the truth in order to achieve some predicted overriding moral benefit and thereby also preserve her or his integrity as a morally autonomous professional (as distinct from, say, a law-abiding citizen).

In light of these basic views on law and ethics and legal and ethical decision-making, what then is the nature of clinical (nursing and medical) decision-making? Primarily, nursing and medicine involve the skilful practice and application of tested principles of applied science and care to prevent, diagnose, alleviate or cure disease, illness and sickness and restore a person’s health and sense of wellbeing. The practices of nursing and medicine are backed by legal and professional sanctions. For example, doctors and nurses can be found financially liable for negligence, and can be deregistered for professional misconduct, or even for civil misconduct unbefitting a professional person (see, e.g. Johnstone 1994; Freckelton & Petersen 2006).

Given this, to say of a decision that it is a ‘nursing decision’ or a ‘medical decision’ in this context is probably to say little more than that it has been made by a nurse or a doctor respectively, and is based on an established body of knowledge and ‘reasonable’ professional opinion on how this knowledge should or should not be applied in a clinical situation. For example, a doctor may venture the ‘reasonable’ medical opinion that if a certain life-saving treatment is stopped the patient will surely die. Or a nurse may venture the ‘reasonable’ nursing opinion that if a certain nursing care is not given the patient will suffer a particular type of harm. It must be understood here, however, that neither of the clinical opinions expressed in these instances is tantamount to expressing a valid moral judgment. For example, to say that a patient ‘will die’ if a certain drug or other treatment (e.g. surgery) is given or withheld says nothing about the moral permissibility or imperatives of giving or withholding the drug or other treatment in question. The ethics of a given clinical act is not implicit in the act itself; this is something which can be determined only by independent moral analysis.

Given these rough comparisons, it can be seen that legal, ethical and clinical decisions can be readily distinguished from one another (see Figure 2.1). What is also obvious is the enormous potential for the respective demands of each of these three types of decisions to come into conflict. For example, a medical decision not to resuscitate a patient in the event of a cardiac arrest (on the grounds that the patient’s condition is ‘medically hopeless’) may be supported by an established body of medical opinion, but nevertheless be deemed morally unsound or even illegal, or both. For instance, the patient’s autonomous wishes may not have been established before the medical decision was made, or the patient’s legally valid consent may not have been obtained to withhold cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in the event of a cardiac arrest. Or, to take another example, a medical decision to continue treating a patient may accord with a ‘reasonable body of medical opinion’, be legal (as in cases where patients have been deemed rationally incompetent under a mental health act), yet be quite unethical if the patient has expressly stated a prior wish not to be treated, and if this expressed wish, contrary to popular medical opinion, is not ‘irrational’.

|

| Figure 2.1 |

We can also imagine cases where a medical decision to cease treatment accords with moral principles but may nevertheless invite legal censure — as in the case of withholding or withdrawing unduly burdensome life-prolonging treatment from severely brain-injured adults, poignant examples of which can be found in the much publicised Terri Schiavo case in the United States (US) (see Gostin 2005; Perry et al 2005; Quill 2005, and other cases that are presented in Chapters 10 and 12 of this text).

Although there is potential for conflict between ethical, legal and clinical decisions, it is not the case that these are always on a direct collision course; indeed, they may even be in harmony with each other, as examples given in the chapters to follow show.

In drawing comparisons between legal, ethical and clinical decisions, there remains another crucial point to be observed: that it is conceptually incorrect to regard nursing or medical decisions per se as synonymous with either legal or moral decisions. This is not to say that we cannot meaningfully speak of nursing or medical decisions as being legally or morally correct or incorrect. On the contrary, it makes the point that, in asserting the legal or moral status of a given clinical (nursing or medical) decision, a judgment independent of the generally accepted scientific or indeed conventional standards of nursing or medicine must be made. In the case of ethics, the moral status of a clinical decision requires independent philosophical/moral analysis and judgment based on relevant moral considerations (e.g. moral rules and principles); and in the case of law, the legal status of a clinical decision requires an independent legal analysis and judgment based on relevant legal considerations (e.g. legal rules and principles).

C odes of ethics

A code may be defined as a conventionalised set of rules or expectations devised for a select purpose. A code of professional ethics by this view could be described as a document that sets out a conventionalised set of moral rules and/or expectations devised for the purposes of guiding ethical professional conduct. It is important to understand, however, that codes of ethics are not ethics per se since they are not a fully developed system of ethics. Nevertheless, codes of ethics tend to reflect a rich set of moral values that have been expressed through a process of extensive consultation, debate, refinement, evaluation and review by practitioners over a period of time, and thus are well situated to function as meaningful action guides.

It is important to state at the outset that codes of ethics can be either prescriptive or aspirational in nature. In the case of prescriptive codes, provisions are ‘duty-directed, stating specific duties of members’ (Skene 1996: 111). In contrast, aspirational codes are ‘virtue-directed, stating desirable aims while acknowledging that in some circumstances conduct short of the ideal may be justified’ (Skene 1996: 111). Either way, codes of ethics have as their principal concern directing:

what professionals ought or ought not to do, how they ought to comport themselves, what they, or the profession as a whole, ought to aim at …

(Lichtenberg 1996: 14)

Codes of ethics are not, however, without difficulties — a point noted almost 100 years ago by the distinguished North American nurse leader and scholar, Lavinia Dock. In a little-known but important essay entitled ‘Ethics — or a code of ethics?’, Dock (1900: 37) challenged:

What, exactly, could a Code of Ethics be? … What are ethics and can they be codified? Do we aim at ethical exclusiveness and shall our ethical development be bounded or limited by a code? ‘Code’ suggests statutes, infringements, penalties, antagonisms. If we have the ethics, we will not need a code. The code is to regulate those who have no ethics, and in proportion as ethical principles are made a part of our natures and lives, our codes and restrictions will shrivel away and die the death of inanition.

Dock (1900) goes on to explain that she is not advocating the total rejection of rules and regulations of professional conduct — to the contrary, particularly since such rules and regulations, as given in a code, could serve as helpful mechanisms ‘to prop up the steps of those who are young in self-government or feeble in self-control’ (p 38). Rather, the issue was not to call codes of rules and regulations ethics, since, as she argued persuasively, there was a real risk that (p 38):

If we call them ethics we may perhaps come to believe that they are all there is of ethics, and presently be worshipping the code rather than the thing, so unreasoning a reverence is there in our souls for statutes, fines, and punishments; so exaggerated a notion of the potency of drafted laws; so strong a tendency to make rules the end and aim of life rather than simply conveniences, changeable contrivances.

Although written over a century ago, Dock’s visionary words are applicable today. Nurses globally would be well advised to be cautious in their use of formally stated and adopted codes of ethics, and to be especially vigilant not to fall prey to ‘worshipping the code’ at the expense of being ethical — and not to fall into the trap of treating the requirements of a code as absolute, and as ends in themselves, rather than as prima-facie guides to ethical professional conduct.

It has long been recognised that a professional code of ethics is an important hallmark of a profession (Bayles 1981; Goldman 1980). Whether professional codes as such have succeeded in fulfilling their intended purpose of ‘formulating the norms of professional ethics’ (Bayles 1981: 25) and guiding ethical professional conduct is, however, another matter. Some have argued that codes of ethics have failed to ensure this; instead, codes of ethics have served to protect the interests of the professional group espousing them, rather than the interests of the client groups whom the professionals are supposed to be serving (Beauchamp & Childress 2001: 5–7; Kultgen 1982: 53–69).

Despite the demonstrable shortcomings of professional codes of ethics, it is evident that many professional codes of ethics have been written with the noble intention of guiding ethically just professional practice. What needs to be understood, however, is that even the most scrupulously formulated and well-intended professional code of ethics is not without its limitations and, in the final analysis, may do little to either guide moral deliberation or ensure the realisation of morally just outcomes in morally problematic situations. In the case of the nursing profession, owing to the complexity of nursing work and the complexity of the contexts in which nurses work, codes of ethics may be quite inadequate to the task of guiding ethical decision-making and conduct. This is particularly so in environments where economic and legal considerations reign supreme and have dominance over other considerations (Meulenbergs et al 2004). Moreover, following a code of ethics will not necessarily protect nurses when they are called upon to defend their actions, say, in a court or disciplinary hearing (see Johnstone 1994: 251–67).

In a 1990 Australian case, for example, involving the alleged unfair dismissal of a registered nurse involved in a case of suspected child sexual abuse, the deputy president of the Industrial Relations Commission of Victoria (where the case was heard) rejected the authority of the ICN (1973) Code for Nurses, which was referred to in defence of the nurse’s actions ( In re alleged unfair dismissal of Ms K Howden by the City of Whittlesea 1990). In this case the deputy president of the commission pointedly criticised the ICN code as being ‘imprecise’ and lacking the ability to provide ‘clear guidance’ in matters requiring fine discretionary professional judgment. He also pointed out that the ‘code in its terms cannot stand alone’ and must be considered in relation to the guidance which is also offered by the law ( In re alleged unfair dismissal of Ms K Howden by the City of Whittlesea 1990). The fact that the ICN code is widely accepted by professional nursing organisations around the world had little bearing on the deputy president’s views in this case.

The legal authority of other codes of nursing ethics/conduct have also been called into question in other cases heard in jurisdictions outside Australia (Johnstone 1994).

One question which arises here is that, if codes of ethics are problematic, and have only limited legal (and, it should be added, moral) authority, should nurses adopt them? The short answer to this question is yes. One justification for this is that, despite their limitations, codes of ethics have an important role to play in the broader schema of professional nursing ethics insofar as they can provide a public statement on the kinds of moral standards and values that patients and the broader community can expect nurses to uphold, and against which nurses can be held publicly accountable. Second, they can also inform those contemplating entering the profession of the kinds of values and standards which they will be expected to uphold, and which, if not upheld, could result in some sort of professional censure. For example, the ICN (2006) Code of Ethics for Nurses makes explicit that a nurse’s ‘primary responsibility is to people requiring nursing care’, and that, in providing care, the nurse will promote ‘an environment in which the human rights, values, customs and spiritual beliefs of the individual, family and community are respected’. If people contemplating entering the profession of nursing are informed of these prescriptions, and do not agree with them, they will be in a better position to make an informed choice about whether or not to enter the profession.

Another justification is that codes of ethics can help with the cultivation of moral character. They can do this by ‘increasing the probability that people will behave in some ways rather than others’ — specifically that they will behave in ‘the right way’ and, equally important, ‘for the right reasons’ (Lichtenberg 1996: 15). As already stated, although codes of ethics do not constitute a system of ethics (at best, they comprise only a list of rules that have been derived from systematic ethical thought), they nevertheless provide people with a reason to think and act ethically, not least by reminding them ‘of the moral point of the sorts of activities they are involved in as members of the particular profession or group’ (Coady 1996: 286). On this point, Lichtenberg (1996: 18) contends:

A code of ethics can increase the probability that people will think about it [what one is doing] — can make it more difficult to engage in self-deceptive practices — by explicitly describing behaviour that is undesirable or unacceptable.

Crucial to the cultivation of moral character, is self-conscious moral reflection. And, as Freckelton (1996: 130) suggests controversially, codes of ethics ‘are a means to this end’. He states (p 130):

They [codes of ethics] have the potential to articulate the characteristics and ideals of a profession and to facilitate consciousness of and discourse about ethical issues. Through the process of moral deliberation thereby engendered, they may operate as the catalysts for ethical conduct both by heightening awareness of ethical priorities and by providing guidance from experienced professionals for the resolution of ethical conundra encountered at a practical level by practitioners … By articulating the parameters of a profession and of acceptable professional conduct by its practitioners, a code defines what a profession is and is not, as well as the limits of proper conduct.

Self-conscious moral reflection and discussion about ethical issues are facilitated by codes of ethics in at least one other important way, namely, by what Fullinwider (1996: 83) describes as supplying a vocabulary (which can be used for the purposes of stimulating ‘moral self-understanding’) and helping to ‘ create a community of users’. To put this another way, by expressing a given set of ethical values, a code of ethics makes discussion and debate of ethical issues possible within a given professional group (community); it provides a (common) moral language, which can be used meaningfully by subscribers to a given code, to identify and discuss matters of moral importance and to advance the task of professional ethics generally in their milieu.

The point remains, however, as already argued, that codes of ethics have only prima-facie moral authority (that is, they may be overridden by other, stronger moral considerations), and hence can only guide, not mandate, moral conduct in particular situations. Further, as Seedhouse (1988: 65) points out, it is important to understand that a code cannot inform a nurse which principles to follow in a given situation, how to interpret chosen principles, how to choose between conflicting principles, or ‘how to decide when it is most ethical to disregard the rules and deliberate instead as a unique and independent individual’ as is sometimes required. Accepting this, and as the examples given in the following chapters show, it can be seen that no code of professional nursing ethics should be regarded as an authoritative statement of universal action guides. Rather, it should be regarded only as a statement of prima-facie rules which may be helpful in guiding moral decision-making in nursing care contexts, but which can be justly overridden by other, stronger moral considerations (see also Biton & Tabak 2003; Meulenbergs et al 2004).

H ospital or professional etiquette

Nothing could be more different from ethics than etiquette. Although both seek to guide behaviour and conduct, they do so in quite different ways and for quite different purposes. Ethics, for example, speaks to morally significant rights and wrongs, with behaviour being guided by critically reflective moral thought and the application of sound moral values which seek to maximise the moral interests of all people equally. Etiquette, by contrast, speaks more to maintaining style and decorum, with behaviour being guided by the unreflective and arbitrary requirements of custom and convention. In application, etiquette paves the way for coordinated, consistent, predictable and, where possible, aesthetically pleasant practice and conduct, and serves only the interests of particular persons in particular circumstances (May 1983). As with legal law, what etiquette might demand in one situation, ethics might reject, and vice versa.

The extent to which the notions of ethics and etiquette can be confused in health care settings is well illustrated by the following case — which demonstrates the reluctance by some health professionals (including nurses) to advise patients to seek a second medical opinion, in the mistaken belief that doing so would constitute a serious breach of ethics.

The case (personal communication) involves a middle-aged woman suffering moderately severe retrosternal chest pain and shortness of breath who presented to the accident and emergency department of a large city hospital. The nursing staff admitted the woman into a cubicle equipped to deal with ‘cardiac emergencies’ and proceeded to perform an electrocardiograph (ECG). The ECG showed a number of cardiac arrhythmias, all of which were suggestive of an acute cardiac condition warranting immediate specialised medical and nursing care. Upon further questioning, it was revealed that the woman was also suffering a mild pain in her left arm (a pain she had ‘never had before’), which is characteristic of cardiac disease. The pain improved, however, while she rested in the casualty department. Her past medical history indicated no known heart disease or any previous incident of chest pain. This was the first time she had ever experienced such symptoms — symptoms which were indicative of significant underlying cardiac disease.

A junior first-year medical resident examined the woman and decided she should be admitted immediately into the coronary care unit for further cardiac monitoring and tests. As required by the hospital’s admission policy, he contacted the registrar ‘on call’ to have his diagnosis confirmed and to arrange the woman’s admission formally. Upon examining the patient, however, the registrar declined to admit her, since there were no ‘cardiac beds’ available in the hospital and he was not convinced that the ECG findings indicated a life-threatening cardiac condition. He discharged the woman, advising her to see her own general practitioner the following morning. He gave her a medical note and a prescription for an oral cardiac anti-arrhythmic agent.

The nursing staff were very concerned, as was the first-year medical resident. All felt the patient should have been seen by another doctor for a ‘second opinion’, but could not decide whether to advise the woman to go immediately to another hospital. After some 20 minutes of deliberation, the attending nursing supervisor concluded it would be ‘unethical’ to advise the patient to go to another hospital for a second examination. The nursing staff and junior doctor involved agreed. The patient walked out of the door and was not informed that it would be in her interests to seek a second medical opinion. At this hospital, it was not ‘standard practice’ to advise patients to seek second medical opinions.

What was at issue here, however, was breaching hospital etiquette. Advising the woman to seek a second medical opinion, in this case, would not have been unethical; indeed, there is considerable scope to suggest that offering such advice was morally obligatory in this case.

Etiquette obviously has its place in the professional and health care arena; it is not without limits, however. Unfortunately, as Blackburn (1984: 189) points out, people do ‘often care more about etiquette, or reputation, or selfish advantage, than they do about morality’. The lesson to be learned here is that acting in accord with hospital or professional etiquette might sometimes be tantamount to acting unethically or immorally — or, in some instances, even illegally. It is, therefore, important that nurses learn to distinguish between the demands of etiquette and those of ethics.

H ospital or institutional policy

Hospital policy or institutional policy is often appealed to in order to legitimise a worker’s actions and, in some cases, to settle a conflict of opinion about what course of action should be taken in a particular situation. In this respect, institutional or hospital policy plays an important practical role — it helps to coordinate ‘the running of the system’ and to make institutional practices consistent and predictable; nevertheless, it also paves the way for uncompromising control. Like legal law and etiquette, institutional policy can be morally bad and in application can seriously conflict with the demands of ethics. The following case (taken from the author’s personal observations) is a good example of how institutional policy can be at odds with ethics.

A 20-year-old woman in advanced premature labour was admitted to the casualty department of a city hospital. She was of a traditional Maori background, married, and the pregnancy had been planned. This was her third premature labour. On the two previous occasions she had spontaneously aborted at around 20 weeks’ gestation. Her current pregnancy was also of approximately 20 weeks’ gestation.

The obstetrics registrar was notified, but failed to appear before the young woman delivered her fully formed male fetus. The fetus was active upon delivery and was noted by nursing staff to have breathed, emitting a faint but audible high-pitched ‘rasp’ as it did so. In accordance with ‘standard hospital procedure’ the fetus was placed in a stainless steel kidney dish, taken immediately away from the mother’s view, and placed, covered with a bedpan sheet, in the sluice room to die. The mother and her family, however, wanted to have ‘the baby’ near, not only to see it but more importantly to perform karakia (a kind of incantation or prayer), as stringently required by ancient Maori custom. 1

Maori enrolled nurses working in the casualty department were greatly distressed by what was happening. As the mother and her family (one of whom was a Tohunga [priest]) were pleading to have the fetus returned, one of the Maori enrolled nurses went to the fetus in the sluice room ‘to be with it, so that it would not die without knowing love’. Crying softly, she also admitted to a registered nurse involved in the case that she was going to offer a prayer ‘for the child as he goes on his way …’ (Makereti 1986).

The doctor had, meanwhile, arrived in the department and examined the mother. He explained to her and her family that the fetus could not be released to them because ‘tests had to be done on it’. He later explained to protesting nursing staff that fetuses delivered at the hospital were generally regarded as ‘hospital property’ and that it was ‘hospital policy to send all aborted fetuses to the laboratory for analysis’. He also explained that the present case was particularly complicated because the fetus was of 20 weeks’ gestation, and had breathed. It was therefore, technically speaking, a ‘live birth’, and thus an autopsy would have to be performed. This, he further claimed, was a legal requirement. Whether in fact this was correct was not known by those present at the time; informal sources subsequently indicated that autopsies cannot be performed without consent, and it is likely that the parents’ claim to the fetus could have been legally upheld. Most of the registered nurses present nevertheless accepted the doctor’s explanation and resigned themselves to ‘hospital policy’.

One registered nurse, however, pressed the matter further and explained to the doctor that the ‘hospital policy’ in this instance was quite inappropriate given the situation at hand, and that to uphold the policy so rigidly stood to violate the Maori family’s rights and interests. At the same time, the fetus had meanwhile been mistakenly submerged in the liquid preservative formalin and taken by a hospital orderly to the laboratory.

Fortunately, the doctor was sympathetic and sought to resolve the difficulties he perceived he would have with the hospital authorities by registering the fetus as being of less than 20 weeks’ gestation, and as not having breathed. Nevertheless, the fetus was not retrieved from the laboratory for another 24 hours, by which time, sadly, considerable damage had already been done. The most the family and the Tohunga could now do was to try and appease the wairua (spirit) through karakia, and to try and persuade it to travel without taking harm with it. The mother’s single room was turned into a marae (meeting place) setting, and a tangi (funeral) commenced. This was an act of sheer desperation, and in part an attempt to explain to the wairua why the violation and act of cruelty had occurred. It was also to grieve for what they had lost, and what would be lost to them forever.

Upholding hospital policy in this case resulted in an unacceptable level of human suffering — suffering which could have been avoided by a more critically reflective approach to the situation. Had those present been more aware of their moral obligations to respect the wishes of the mother and her family, a morally tolerable outcome could have been achieved. Fortunately, as a result of this particular incident, the hospital policy was revised, making it easier for Maori mothers to claim their fetuses lost through miscarriages or premature births.

This case demonstrates a situation where ethics is quite distinct from institutional policy, and where a review of ethical considerations may prompt reform of policy. It also shows how respect for hospital policy is not sufficient to ensure the realisation of morally desirable or morally tolerable outcomes.

P ublic opinion or the view of the majority

Public opinion is often cited in defence of the ‘ethics’ of something such as the moral permissibility of abortion, euthanasia or the use of fetal tissue for research. For example, those in favour of the legalisation of euthanasia will commonly cite public opinion polls favouring the legalisation of euthanasia to support their stance.

Ethics is not something that can be determined or decided reliably by public opinion, however. If ethics were merely a matter of public opinion, all we would have to do is conduct an opinion poll and establish a ‘majority view’ on a matter to find out whether it was morally right or wrong. If ethics was determined by mere public opinion, our moral standards would be rendered hopelessly and unacceptably changeable, making it extremely difficult to practise ethically. Consider the following example.

In 2002 it was reported that most Australians (including Catholics) supported the use of fetal tissue in medical research (Kissane 2002: 7). A survey of 9293 people (including 2120 Catholics) found that 36% strongly approved and 40% approved (that is, a total of 76% approved) the use of cells from a fetus for ‘testing new ways to treat cancer or Parkinson’s or other serious diseases’ (Kissane 2002: 7). The survey also found that 19% of respondents believed that human life began at conception, but that most believed the fetus was not human 2–3 months of gestation and 83% believing the fetus was not human until 4–5 months, ‘when the mother could feel it move’ (Kissane 2002: 7). It was suggested that these findings had enormous implications for the abortion debate (Kissane 2002: 7) — the main implication being that if it is permissible to experiment on fetuses (at least before the 3rd month of gestation), then it is also permissible to perform abortions (at least before the 3rd month of gestation).

If ethics was just a matter of public opinion, in this example we would be committed to accepting that the fetus is not ‘human’ until the 2nd, 3rd, 4th or 5th month of gestation and that it is morally acceptable to experiment on fetuses (at least before the 3rd month of gestation) since it is not ‘human’. The human fetus is, of course, genetically human from the moment of conception even though public opinion, in this instance, would however have us believe otherwise and, inconsistently, across a continuum of time, that is, of 2, 3, 4 and 5 months. The issue of when the fetus becomes a human being is, however, a different matter entirely and, unfortunately, not covered in the report. Nevertheless, even if this question was settled in favour of ‘humanhood’, it is not clear whether this would be sufficient to change public opinion. If public opinion were to change — and it turned against the permissibility of using fetal tissue for research purposes — we would be committed to accepting the impermissibility of using fetal tissue for research purposes even when this could result in finding a cure for terrible diseases. A public opinion view of ethics, in this instance, could therefore result in a change in the judgment on the rightness or wrongness of using fetal tissue for research purposes from one day to the next.

A public opinion or majority view of ethics is open to serious objection. On a philosophical level, it violates a formal and necessary requirement for sound moral judgments, notably the requirement for internal consistency (Kuhse 1987: 25). Its findings are liable to reflect sudden and unpredictable changes in attitudes and opinions, and thus are morally unreliable. As well as this, on a more pragmatic level, there is the troubling possibility that public opinion might be mistaken or wrong or misguided — particularly where it has been manipulated by pressure groups, politicians or by the media, as occurred in the much publicised ‘Children Overboard’ incident that occurred in Australia in the lead-up to the 2001 Federal election. The incident involved the public misrepresentation of photographic images and false claims by Federal government politicians that asylum seekers, who were attempting to enter Australian territory ‘illegally’ by sea, had ‘deliberately’ thrown their children overboard from the boat they were on in order to force their rescue and subsequent entry into Australia via the HMAS Adelaide, a nearby naval ship. It was later revealed, however, and subsequently verified by a Senate Inquiry into the matter, that no children had, in fact, been thrown overboard (Senate Select Committee on a Certain Maritime Incident 2002). In the lead-up to the Federal election on 10 November, this incident was used along with other incidents (e.g. the Tampa rescue of Afghan refugees) to support the Federal government’s ‘hardline political response to unauthorised arrivals’ and to sway public opinion against asylum seekers seeking refuge in Australia by portraying them (demonising them) as ‘faceless, violent queue jumpers’ (Australian Broadcasting Corporation [ABC] 2002), as ‘illegal immigrants’ (rather than ‘genuine’ asylum seekers) and as people of poor moral character (‘What kind of people throw their children overboard?’, Senate Select Committee on a Certain Maritime Incident 2002). Post election analyses indicated that the ‘Children Overboard’ incident had influenced public opinion in favour of the Federal government’s tough (some would say, inhumane) policies on the admission and detention of refugees and asylum seekers in Australia and contributed to the Federal government’s re-election in 2001 (see also Hamilton & Maddison 2007; Manne 2005).

There is also the risk of opinion polls being fraudulent. As one woman wrote in a letter to the editor of The Age:

If I felt strongly enough about the issue at hand [television phone-in polls] I could have spent the evening by my phone and, with the simple touch of one button, registered votes almost continuously without anyone being any the wiser to my hundreds and possibly thousands of votes …

… Unfortunately many people never question the validity of opinion polls and instead take them at face value. I suspect that many think they represent general opinion, otherwise why conduct them.

(Romanin 1988: 12)

It is not being denied here that public opinion is an important and relevant consideration that warrants some attention when deciding ethical issues. On the contrary, public opinion which reliably indicates a certain view on a given matter might well be a useful tool in guiding beneficial social policy and law reforms. However, public opinion is not infallible in matters of morality and mere common acceptance does not imply validity (Brandt 1959: 57). The moral rightness or wrongness of an act can be decided only by sound critical reflection and wise reasoning, not merely by public opinion or ‘collective desire’ or ‘collective preference’.

F ollowing the orders of a supervisor or manager

Following the moral commands of another is quite incompatible with the notion of ethics and the autonomous moral thinking that underpins it (for reasons that will be explained in Chapter 3). Moreover, it paves the way for the abdication of moral responsibility and accountability. Supervisors have supervisors, and these supervisors have still more supervisors. A hierarchical system of authority may mean in practice that, because everyone is accountable for a given action, it is difficult or impossible to decide who is to be held ultimately accountable (Barry 1982: 13).

A classic example of this occurred at Waikato Hospital, New Zealand, in 1982. The incident in question involved a 28-year-old woman who died after being given an incorrectly prescribed dose of morphine. At the coronial inquiry into her death, it was revealed that the charge nurse who administered the 50 milligram intramuscular dose of morphine did so on the insistence of the prescribing ‘doctor’ (who was in fact a final-year medical student from Australia). The prescribing ‘doctor’ in turn insisted that she ‘did not prescribe the morphine, but simply passed on [the covering registrar’s] prescription for the nurse to administer’ ( Waikato Times 1984b: 3). The medical registrar, in turn, claimed that he had worked from eight in the morning on Saturday to midday Sunday, and had only had four hours’ sleep during that time — implying that ‘the system’ was to blame. The medical consultant under whom the registrar was working meanwhile stated that ‘if he was asked’ he would not regard the duties of the medical student as being ‘those of a house surgeon’ (the New Zealand term for medical resident) — implying that his registrar was ultimately responsible ( Waikato Times 1984a: 1). The medical superintendent, in turn, stated that the registrar ‘should have been in charge of prescribing narcotics’ ( Waikato Times 1984a: 1), while the Waikato Hospital Board suggested that ‘no one person be blamed for the overdose’ ( Waikato Times 1984b: 3).

The coroner is reported to have concluded that it would be quite ‘unfair, unkind and not based on the evidence’ to blame the medical student who prescribed the morphine causing the woman’s death. On the basis of the coroner’s overall findings, the police did not press charges.

Admittedly this case emphasises more the issue of legal accountability and offers some salutary lessons about ‘system accountability’ and human error management in health care (see Kohn et al 2000; Reason 2000; Sharpe 2004) — an issue that will be explored further in Chapter 6 of this text. However, this case also highlights some important lessons about the possible relationship between legal and moral responsibility and accountability. Legal and moral responsibility and accountability travel a common path, as made evident by the much noted Bormann defence, named after Martin Bormann, third deputy under the Nazi regime of World War II, who argued in defence of his involvement in wartime atrocities that he was ‘just following orders’ (Barry 1982: 13). This kind of defence is a convenient ‘moral cop-out’ for those who have no sense of moral accountability, or a poorly developed sense, and who ordinarily try to justify their behaviour as Bormann did: ‘I was told to do it’; ‘I was expected to do it’; ‘I was just doing my job’; ‘That’s how things operate around here’; and so forth (Barry 1982: 13).

The outcome of the 1945–46 Nuremberg trials made it abundantly clear that a plea of following the orders of one’s superiors was not an acceptable or a legitimate defence in the eyes of the law. Such a precedent had already been well established for nurses as early as 1929, however, with the successful prosecution in the Philippines of a newly graduated nurse by the name of Lorenza Somera, who was found guilty of manslaughter, sentenced to a year in prison, and fined 1000 pesos because she had followed a physician’s incorrect drug order (Grennan 1930). In court it was proved that the physician had ordered the drug, that Somera had verified it, and that the physician had administered the injection. But, as Winslow (1984) writes, ‘the physician was acquitted and Somera found guilty because she failed to question the orders’. The case stunned nurses around the world. A campaign of protest was organised, and Somera was given a conditional pardon before serving a day of her sentence.

In an institutional setting, it is very easy to rationalise moral ‘unaccountability’:

So many people, even institutions, can get involved at so many levels that moral buck-passing can become the order of the day. The blind pursuit of prestige and profits also blurs moral accountability. And most important, the intense pressure to keep one job and to secure promotions can be used to justify almost anything. The point is that working within an organisation provides easy excuses for abdicating personal moral accountability for decisions and actions.

(Barry 1982: 13)

One way of avoiding this abdication is to draw a firm distinction between ethics and following the orders of a supervisor or manager, and to recognise that moral demands are always the overriding consideration, irrespective of a supervisor’s or a manager’s orders.

T he task of ethics, bioethics and nursing ethics

In considering what ethics is, and what it is not, it is also important to have some understanding of exactly what ethics, in its broadest sense, is attempting to achieve; in short, what is the task of ethics and to what extent do bioethics and nursing ethics respectively contribute to this task?

In identifying and exploring the task of ethics, it is necessary to give a brief historical overview of the development of Western moral thinking. The task of ethics has been the subject of rigorous philosophical debate for almost 3000 years. In the Platonic dialogues, for example, we are told that the ultimate task of morality is to find out ‘how best to live’ or, in other words, how to lead ‘the good life’ and enjoy supreme wellbeing (Allen 1966: 57–255). For the British philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), the task of morality is a little different: notably, to find a device that will ensure mutual agreement and cooperation among each of society’s members. It was Hobbes’ view that, without such a device, the prospects of human survival would at best be slim (Hobbes 1968: 205).

Hobbes’ concerns were echoed almost a century later by the Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711–76), who insisted, among other things, that morality was a subject of supreme interest since its decisions had the very peace of society firmly at stake (Hume 1888: 455). Like Hobbes, Hume recognised that the human mind was more than capable of courting the undesirable qualities of ‘avarice, ambition, cruelty [and] selfishness’; and, like Hobbes, he recognised that society’s hope for peace depended very much on the formulation of certain rules of conduct (Hume 1888: 494–6). These rules of conduct need to be developed and enforced precisely because people fail to pursue the public interest ‘naturally, and with a hearty affection’ (pp 496).

The influential German philosopher, Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) took a slightly different view from his predecessors. Unlike Hobbes and Hume, he saw the task of ethics (or rather, moral philosophy) as being ‘to seek out and establish the supreme principle of morality’ (Kant 1972: 57). Like those before him, Kant recognised that persons were vulnerable to being ‘affected … by so many inclinations and lacked the power to conduct their life in accordance with practical reason’. Kant went on to argue that as long as the ‘ultimate norm for correct moral judgment’ is lacking, morals themselves will be vulnerable to corruption (p 55).

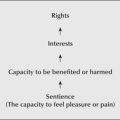

Kant’s overall investigation succeeded in providing a supreme, although not uncontroversial, principle of morality for guiding human actions. Upholding the tenets of ethical rationalism (now regarded as a controversial thesis), this principle took the form of a categorical imperative which essentially commands that rational autonomous choosers should ‘act only on that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it should become universal law’ (Kant 1972: 84). In other words, act only on those moral rules and principles which you are prepared to accept apply to all other people as well. His final analysis made clear that the influences of self-interest and/or of individual ‘feelings, impulses and inclinations’ could have no place in a system of sound morality (p 84). If ‘rational agents’ are to act morally, they must act in strict accordance with the dictates of ‘rational moral law’.