Obstetrics and Gynaecology Emergencies

Edited by Anthony Brown

19.1 Emergency delivery and complications

Stephen Priestley

Introduction

Occasionally, a doctor working in an emergency department (ED) is faced with caring for a patient in labour and is required to manage a spontaneous vaginal delivery. This situation is generally accompanied by much anxiety on the part of the ED medical and nursing staff, but it is important that a calm, systematic approach is taken to minimize the risk of an adverse fetal or maternal outcome.

This chapter describes the management of a normal delivery in the ED and provides a brief outline of the recognition and management of abnormal deliveries and selected peripartum complications.

Setting

There are a number of settings when childbirth may need to occur in an ED. Pregnant patients at different gestational ages may present to the ED in varying stages of labour. Immediate management will depend on the availability of obstetric services, the gestational age and on both the stage of labour and its anticipated speed of progression.

Safe transfer to a delivery suite when there is adequate time is always preferable to delivery in the ED. If there is no delivery suite available, or a patient arrives with full cervical dilatation and the fetal presenting part is on the perineal verge and there is no time for transfer to an appropriate facility, then arrangements need to be made rapidly to perform the delivery in the ED. In these situations, the emergency physician should prepare for two patients, both potentially needing care.

Precipitate labour

Patients who have precipitate labour – an extremely rapid labour lasting less than 3 hours from onset of contractions to delivery, more common in the multiparous – may have to stop in the ED even when en route to the delivery suite, or another hospital, because of the rapidity of the labour.

Concealed or unrecognized pregnancy

The diagnosis of a concealed or unrecognized pregnancy may also be made in the ED. Concealed pregnancies occur most commonly in teenage girls who do not tell anyone that they are pregnant and receive no antenatal care. Unrecognized pregnancy occurs most commonly in obese females who may present to the ED complaining of abdominal pain or a vaginal discharge and are found to be pregnant and/or in labour. Women with intellectual impairment or mental illness are another group who may present with an unrecognized pregnancy.

‘Born before arrival’

The term ‘precipitous birth’ or ‘born before arrival’ (BBA) is commonly associated with precipitate labour and refers to women who deliver their baby prior to arrival at a hospital, usually without the assistance of a trained person. On arrival in the ED, both the mother and baby require assessment and may need resuscitation and completion of the third stage of labour. The term precipitous birth is also commonly used to describe deliveries that occur in the emergency department or areas outside of a labour and delivery suite.

The incidence of BBA is low but depends on the population studied. In Australia, the incidence of precipitate labour is approximately 1–2% in spontaneous non-augmented labours.

History

Assessment of the patient in labour in the ED includes obtaining information regarding gestational age, antenatal care, progression of the pregnancy, past obstetric and a medical history. Always enquire if the patient has a copy of her antenatal care record with her. Take a careful history regarding the onset and timing of contractions and the presence and nature of fetal movements, in addition to a history of vaginal bleeding or discharge, which may represent the rupture of membranes.

Delivery in a hospital where there is no delivery suite should include immediate contact by telephone with the nearest or most appropriate obstetric unit to obtain advice and to organize transfer of the mother and newborn.

Gestational age

The gestational age may be determined from the last normal menstrual period (LNMP) if this is known. Naegle’s rule is the most common method of pregnancy dating. The estimated date of delivery (EDD) is calculated by counting back three months from the last menstrual period and adding seven days. As an example, if the last menstrual period is December 20, then the EDD will be September 27. This method assumes the patient has a 28-day menstrual cycle with fertilization occurring on day 14. Inaccuracy occurs because many women do not have regular 28-day cycles, or do not conceive on day 14 and many others are not certain of the date of their last period.

Antenatal ultrasound

Antenatal ultrasound is useful in gauging the estimated date of confinement (EDC) where dates are uncertain, remembering that scans performed later in the pregnancy are less accurate in dating the gestational age of the baby than those performed early. Additionally, a rough estimation of the gestational age of the baby can be made by abdominal examination; between 20 and 35 weeks there is correlation between gestational age and the height of the uterine fundus measured in centimetres from the pubic symphysis.

Past obstetric history

The past obstetric history should include the duration and description of previous labours, the types of deliveries and the size of previous babies, in addition to a history of a previous caesarean section, the use of forceps or vacuum extraction, a neonatal death and history of abnormal presentation, shoulder dystocia, prolonged delivery of the placenta or a postpartum haemorrhage.

Maternal medical conditions

Maternal conditions, such as cardiac and respiratory disease, diabetes, bleeding diathesis, hepatitis B and herpes simplex, should be documented. Record all drugs whether prescribed, over-the-counter or illicit that the patient is taking. The presence of any bleeding or other complications during the pregnancy should also be noted. Obtain the results of antenatal investigations, including a full blood count, blood group, hepatitis-B status, HIV and syphilis serology.

Examination

General examination

A general physical and obstetric examination to confirm the progression of labour, the number of babies and the presence or absence of any complications related to the pregnancy and labour is made. In hospitals where there is a delivery suite, a member of that unit (usually a midwife) is called to attend the ED either to assist with immediate transfer to the delivery suite if possible, or with the assessment and conduct of the labour within the ED. Occasionally, a member of the ED staff will hold a midwife certificate and this staff member should be tasked to assist with labour and delivery.

The general examination includes particular emphasis on vital signs and the abdominal and pelvic examination. Examine the breast, nipples, heart and chest and perform a urinalysis looking for evidence of infection, glucose or proteinuria, which may be associated with pre-eclampsia (see Chapter 19.7).

Abdominal examination

Perform an abdominal examination to ascertain the height of the fundus, the lie and presentation of the fetus and to make an assessment of the engagement of the presenting part. The presence of scars and extrauterine masses should be noted. Assess the frequency, regularity, duration and intensity of uterine contractions.

Fetal heart rate

Count the fetal heart for 1 minute using an ordinary stethoscope, Pinard or a Doppler stethoscope, which should normally be between 110 and 160 beats/min. Count the fetal heart for at least 30 seconds following a contraction. If bradycardia is detected, give the mother oxygen and position her in the left lateral position to ensure that uterine blood flow and fetal oxygenation is optimized.

If post-contraction bradycardias persist despite these measures give an intravenous fluid bolus and seek specialist obstetric advice. Note any vaginal bleeding or discharge and record the amount, remembering haemorrhage may also be concealed. Assess the colour and character of any amniotic fluid, looking for evidence of meconium staining.

Vaginal examination

Perform an aseptic vaginal examination with the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position to assess the effacement, consistency and dilatation of the cervix, the nature and position of the presenting part (i.e. vertex or breech) and to exclude a cord prolapse. If unsure of the nature of the presenting part, a portable ultrasound can aid in diagnosis.

The exception to performing a vaginal examination is the gravid patient with active vaginal bleeding who should be evaluated with an ultrasound to exclude placenta praevia, before performing any pelvic examination.

If the membranes are intact, there is no indication to rupture them if the labour is progressing satisfactorily, as there is an increased risk of cord prolapse when the presenting part is not engaged in the pelvis. After the vaginal examination, apply a sterile perineal pad and allow the mother to assume whichever position gives her the most comfort, while avoiding a totally supine position as this has the potential for inferior vena cava (IVC) compression by the gravid uterus.

Transferring the patient

After this assessment, the decision whether to transfer the patient to a delivery suite either within the hospital, or at a distant hospital, must be made. Cervical dilatation greater than 6 cm in a multiparous patient and 7–8 cm in the primiparous makes transfer to a distant hospital a hazardous process, because of the risk of rapid progression to full cervical dilatation and imminent delivery of the baby.

The availability and type of transport and personnel and the distance to be travelled must be carefully considered. Consult with the obstetric unit regarding the safety of transfer and make arrangements for reception of the patient.

Management

Preparation for delivery

Ongoing assessment of maternal temperature, blood pressure, heart rate and contractions should be performed and recorded. Fetal heart rate should be counted every 15–30 minutes up to full cervical dilatation and every 5 minutes thereafter. The fetal heart rate is best measured with a Doppler device, commencing towards the end of a contraction and continuing for at least 30 seconds after the contraction has finished.

Unless there is a clear indication for an intravenous line, such as a history of postpartum haemorrhage or antepartum haemorrhage, bleeding tendency, evidence of pre-eclampsia or history of a previous caesarean section, then placement for the normal delivery is unnecessary. Perform simple venepuncture for a haemoglobin and blood group and put some blood aside for cross-matching.

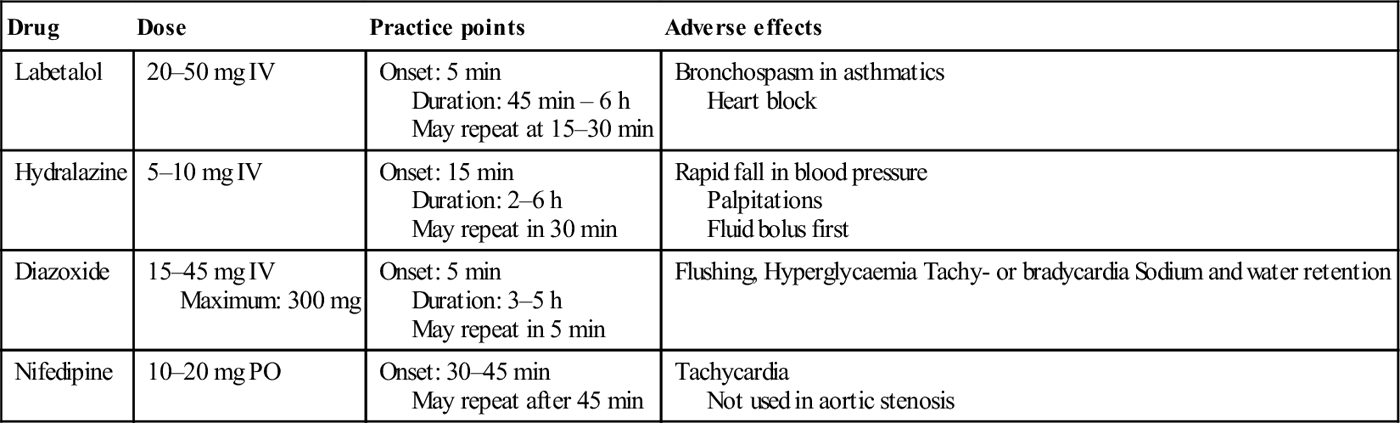

Equipment and drugs

Obtain a delivery pack, sterile surgical instruments and oxytocic drugs and place close by (Table 19.1.1). Resuscitation equipment and drugs should be available. Assemble personnel with clear task delegation, remembering that reassurance and emotional support for the mother and the mother’s partner is crucial during the entire labour. A specific member of staff may be delegated to provide this.

Table 19.1.1

Equipment and drugs required for emergency delivery

| Equipment | Drugs |

| Three clamps – straight or curved (e.g. Pean) | Adrenaline 1:10 000 |

| Episiotomy scissors | Oxytocin 10 units |

| Scissors | Ergometrine 250 μg |

| Suture repair set | Vitamin K 1 mg |

| Absorbable suture material | Lignocaine 1% |

| Sterile drapes | Naloxone 400 μg/1 mL |

| Huck towels | Glucose 10% |

| Sterile gloves | |

| Soap solution | |

| Sterile bowls | |

| Neonatal resuscitation equipment including appropriately-sized suction catheters, oropharyngeal airways, masks, self-inflating bag (approximately 240 mL), endotracheal tubes, stylets, laryngoscopes, end-tidal CO2 detector device, neonatal oxygen saturation probe | |

| Umbilical vein catheters, overhead warmer, clock with timer in seconds, warmed towels, and feeding tubes for gastric decompression |

If a midwife or doctor experienced in delivery is available then they should assume control of the procedure and continue the assessment of the progression of labour and conduct the delivery of both the baby and the placenta. A doctor or nurse with some experience in neonatal or paediatric resuscitation should perform a rapid assessment of the newborn immediately after the delivery of the baby, to ascertain the need for resuscitation.

Conduct of labour

Labour is divided into three stages: the first stage is from the onset of regular contractions to full (10 cm) dilatation of the cervix. The second stage is from full dilatation of the cervix to delivery of the baby and the third stage is from the birth of the baby until delivery of the placenta. A full description of the detailed management of the three stages of labour is beyond the scope of this chapter, but a brief summary of the management of a normal vertex delivery is described.

First stage

Examine the patient abdominally and vaginally as necessary to follow the progress of the labour. As mentioned earlier, perform measurement and recording of maternal vital signs and fetal heart rate. Gently wash the perineum with a non-irritating soap solution, such as 0.1% chlorhexidine, particularly when operative vaginal delivery by forceps or vacuum extraction is anticipated. Shaving, urinary catheterization or enema administration are not required.

The average duration of the first stage of labour in primiparous patients is 14 hours and, in subsequent pregnancies, is 6–8 hours.

Analgesia

Analgesics are helpful for the patient with significant discomfort and are not injurious to the fetus. The timing and dose of analgesia must be decided with due regard to the stage and rate of progression of labour, in addition to the mother’s wishes and birth plan.

Inhaled nitrous oxide is simply delivered, acts quickly, is rapidly eliminated and does not affect the fetus. It is usually provided initially in a dose of 50% N2O mixed with 50% oxygen but the N2O dose can be increased to 70% maximum by delivery systems available in many emergency departments.

Opiate analgesia is also commonly used, though is generally not recommended within 4 hours of predicted delivery, meaning that it is unlikely to be used in a precipitous delivery in the emergency department. Morphine is preferred to pethidine as the active metabolite of IM pethidine has a longer half-life in the newborn, compared to IM morphine. Major opiate side effects include maternal drowsiness, nausea and vomiting. While there is no clear evidence of major adverse effects at birth, the newborn may have respiratory depression and drowsiness which may interfere with breastfeeding [1].

Second stage

Spontaneous delivery of the fetus presenting by vertex is divided into three phases: delivery of the head, delivery of the shoulders and delivery of the body and legs. The second stage of labour begins when the cervix is fully dilated and delivery will occur when the presenting part reaches the pelvic floor.

The normal duration of this stage in the absence of regional anaesthesia ranges from 20 to 60 minutes in the primiparous, down to 10–30 minutes in the multiparous patient. Prolongation of the second stage is defined as 2 hours or more in the primiparous patient and 1 hour or more in the multiparous patient. Preparations for delivery including cleansing are made as described earlier. Drape the patient in such a manner that there is a clear view of the perineum.

Maternal position

Either a dorsal lithotomy or lateral Sims’ position may be used for delivery. The dorsal lithotomy position is recommended for inexperienced operators, as it is easier to visualize and manually control the delivery process, or perform an episiotomy. In the dorsal lithotomy position, the mother should be tilted over to the left side using a pillow or soft wedge, to avoid compression of the inferior vena cava by the gravid uterus and possible maternal hypotension and fetal hypoxia.

Episiotomy

When the presenting part distends the perineum, delivery is imminent. Consider an episiotomy at this time, but this should not be routine. Episiotomy refers to a surgical incision of the female perineum performed by the accoucheur at the time of parturition. The primary reason to perform an episiotomy is to prevent a larger spontaneous, irregular laceration of the perineum, particularly one that extends into the rectum. It is performed with scissors when the perineum is stretched and distended, just prior to crowning of the fetal head, following infiltration of a posterior area of the peritoneum with 5–10 mL of 1% lignocaine (lidocaine) between contractions.

Commonly, a mediolateral perineal incision is made beginning at the posterior fourchette and extended towards the ischiorectal fossa. A midline episiotomy is no longer recommended due to an increased risk of tears extending through to the rectum. The patient should be encouraged to bear down during contractions and to rest in between.

Delivery of the head

Delivery of the head must be controlled by the accoucheur so that the head extends slowly after crowning and does not ‘pop out’ of the vagina. Placing the palm of one hand over the head to control its extension most easily achieves this. At this point, the patient should cease actively pushing and may need to be instructed to pant or breathe through her nose, in order to overcome a desire to push. The accoucheur’s second hand covered with a sterile gauze pad or towel may be used gently to lift the baby’s chin, which can be felt in the space between the anus and the coccyx.

As the occiput descends under the symphysis pubis, extension of the head occurs and progressively the forehead, nose, mouth and finally chin emerge. Suctioning of the nasopharynx and oropharynx prior to birth of the shoulders and trunk should not be done routinely even in the presence of meconium-stained liquor [2,3].

In 25–30% of patients, the umbilical cord is looped around the neck (nuchal cord), which should be checked for. Usually, it is only loosely looped and can be drawn over the head. If this is unsuccessful, another method is to bring the cord caudally over the shoulders and deliver the baby through the cord and then unwind it after delivery. When these manoeuvres are unsuccessful, delivery of the baby without reduction of the cord may be possible (somersault manoeuvre). If none of the techniques seem feasible and the cord is too tight to be reduced, the cord is divided by placing two clamps on the cord 2–3 cm apart and cutting the cord in between them. Release of additional loops is now straightforward by unwinding the clamped ends around the neck.

The baby’s head, having been delivered face down in the most common occipito-anterior position, is allowed to ‘restitute’ (or correct) to one or the other lateral position.

Restitution and delivery of the shoulders

Once the head has restituted, the shoulders will lie in an antero-posterior plane within the pelvis and delivery of the shoulders is now effected taking great care not to allow the perineum to tear. Usually, the anterior shoulder slips under the symphysis pubis with the next contraction by exerting gentle downward and backward traction on the head to facilitate this. Do not use excessive force as this may result in a brachial plexus injury.

On delivery of the anterior shoulder, lifting the baby up will deliver the posterior shoulder followed by the body and lower limbs. Grasp the baby firmly with one hand, securing the infant behind the neck and the other encircling both ankles and place on the mother’s abdomen. The baby is slippery as a result of being covered with vernix and should never be held with one hand alone. Dry the baby and wrap in a warm blanket to minimize heat loss and record the time of birth.

Clamping the cord

There is no need to cut the cord immediately if the baby is breathing spontaneously and is close to term. There is benefit in delaying cord clamping in preterm and possibly term infants, as more blood is transferred from the placenta to the infant when clamping is delayed [4]. Perform an assessment of the baby with Apgar scoring to determine the need for resuscitation.

If the baby is preterm or requires resuscitation, quickly clamp the cord following delivery and transfer the baby for further assessment and resuscitation to a resuscitation trolley that has a radiant heat source. Apply an umbilical clamp 1–2 cm from the baby’s abdomen to cut the umbilical cord and trim the cord approximately 0.5 cm above the plastic clamp.

Apgar score

If circumstances permit, the Apgar score should be calculated. This score allows easy communication of a baby’s status between providers and indicates a basic prognosis for the newborn. It is obtained at 1 minute and 5 minutes after birth, with a score from 0 to 10.

The following acronym approach can be used to remember the five categories, with each scored on a scale from 0 to 2:

A: Appearance (0: pale or blue; 1: pink body, blue extremities; 2: pink body and extremities)

P: Pulse (0: absent; 1: less than 100 beats/min; 2: more than 100 beats/min)

G: Grimace (0: absent; 1: grimace or notable facial movement; 2: cough, sneezes, or pulls away)

R: Respiration (0: absent; 1: slow and irregular; 2: good breathing with crying).

The Apgar score can be calculated after the delivery and resuscitation is complete [5].

Use of oxytocics

Following the birth of the baby, palpate the woman’s abdomen to exclude the possibility of a second fetus when an antenatal ultrasound result is unavailable and administer an oxytocic agent if none is present. The most common is oxytocin at a dose of 10 units given intramuscularly, or 5 units intravenously as a slow bolus. An alternative is ergometrine in a dose of 250 μg intramuscularly, or slowly intravenously but, as this agent is associated with nausea, vomiting and hypertension, it is unsuitable for use in pre-eclampsia, eclampsia or hypertension.

Third stage

After administration of the oxytocic agent, look for signs of separation of the placenta from the uterine wall. Three classic signs of placental separation are: (1) lengthening of the umbilical cord; (2) a gush of blood from the vagina signifying separation of the placenta from the uterine wall; and (3) change in the shape of the uterine fundus from discoid to globular, with elevation of the fundal height.

Following separation, and once the uterus is firmly contracted, apply traction on the cord in a backward and downward direction with one hand, while the other is placed suprapubically to support the uterus. Cease traction if the cord feels as though it is tearing.

Placental inspection

As the placenta appears at the introitus, traction is then applied in an upward direction and the placenta is grasped and gently rotated to ensure that the membranes are delivered without tearing. Inspect the placenta and membranes to look for any missing segments or cotyledons, or evidence of a missing succenturiate ‘accessory’ lobe, which may prevent the uterus from contracting properly if they remain within the uterus.

Uterine tone

Rub over the uterus to facilitate contraction and expulsion of clots. A common cause of postpartum haemorrhage is incomplete uterine contraction as a result of clots or tissue remaining within the cavity, which may be expelled by massaging the fundus or by manual removal under anaesthesia. Further oxytocics may be necessary.

Bleeding may also occur from other sites, so always perform a careful examination of the cervix, vagina, episiotomy wound and perineum following delivery. Full examination of the cervix for ongoing bleeding will require anaesthesia. The episiotomy wound and any other lacerations may be repaired with a synthetic absorbable suture.

Observations

Observations taken following the birth of the baby should include:

Newborn care

Keep the baby warm and dry and record the baby’s vital signs, Apgar scores and weight. If vitamin K is available, administer it to the baby as a deep intramuscular 1 mg injection.

Disposition

Disposition of mother and baby to an obstetric unit either within the hospital or at a distant hospital should then be made once both are stable. The important information that should be provided includes the time of birth, drugs given to either mother or baby and the Apgar scores of the baby. Include the results of any blood tests and a copy of the observations. If either mother or baby is unstable, then early consultation with the appropriate referral service is mandatory regarding the optimum timing and nature of the transfer.

Complications of delivery

Breech delivery

Breech presentation occurs in 3–4% of all deliveries, reducing in incidence with advancing gestation. It is associated with a morbidity rate three to four times greater than that of a normal cephalic delivery. Breech presentation is more common with prematurity, as the final natural rotation in the pelvis may not have occurred, and is associated with a greater incidence of fetal distress and umbilical cord prolapse. The most feared complication is head entrapment, which can lead to fetal asphyxiation and death.

In the normal cephalic presentation, the head maximally dilates the birth canal, allowing the rest of the body to descend unobstructed. However, with a breech presentation, the head emerges last and can become entrapped by incomplete cervical dilatation [6,7]. Delivery of a breech presentation is often performed by caesarian section when available [7,8].

Circumstances, such as precipitous delivery, lack of prenatal care, prematurity and the mother’s preference for vaginal delivery, can place an emergency medicine physician in the situation of managing a breech delivery. The following is relevant to the emergency department when vaginal delivery is imminent without obstetric backup or if the physician is concerned about fetal demise.

Management of breech delivery

Immediate obstetric expertise should be requested urgently, while preparations are made for neonatal resuscitation. It is critical for the emergency physician to avoid manipulating the fetus, but rather to allow the delivery to occur spontaneously as far as possible.

Perform an episiotomy as the fetal anus is climbing the perineum. Allow maternal effort to deliver the baby spontaneously to the umbilicus, delivering the legs with knee flexion. Do not apply traction to the fetus, as this may cause fetal head extension which leads to entrapment of the head and greatly increases the risk of asphyxiation [9]. A loop of umbilical cord may be pulled down and allowed to hang. The mother is encouraged to bear down until the trunk becomes visible up to the scapula. Then rotate the trunk until the anterior shoulder delivers. Subsequent rotation of the trunk in the opposite direction results in delivery of the posterior shoulder.

Once the shoulders are delivered an assistant should provide downward pressure in the suprapubic area to keep the fetal head flexed while the accoucheur delivers the head either with the application of forceps, or by placing the left hand into the vagina and pressing on the maxilla to cause further neck flexion while the other hand grasps a shoulder and applies firm traction in the line of the baby’s hips, taking care not to extend the head. The combined neck flexion, traction on the fetus toward the hip/pelvis and the suprapubic pressure on the mother/uterus allows for delivery of the head of a breech infant (Mauriceau Smellie Veit manoeuvre).

Shoulder dystocia

Shoulder dystocia occurs when the anterior shoulder of the baby cannot be delivered under the pubic symphysis. It is one of the more frightening complications of vaginal delivery and, while some at-risk patients may be identified, it is frequently unexpected. Estimates of the incidence is between 0.2 and 3.0% depending on the exact definition used [9]. Important steps in management are recognizing the at-risk patient, calling for assistance early and understanding the manoeuvres to deliver the fetus. At-risk patients may have a large baby, gestational diabetes or have had a previous shoulder dystocia. Notably, the most relevant risk factor for an emergency physician performing emergency delivery is in fact a precipitous delivery – which is frequently the antecedent to the mother delivering in the emergency department in the first place [9]. However, in many cases, there are no predisposing factors.

Recognizing shoulder dystocia

As it is not possible to predict which deliveries will be complicated by shoulder dystocia, the emergency physician must be prepared for it. Following delivery of the fetal head, the anterior shoulder does not deliver spontaneously, or with gentle traction by the accoucheur. Instead, the anterior shoulder becomes caught immediately above the symphysis. The first sign of shoulder dystocia is retraction of the fetal chin into the perineum, following the delivery of the head.

Delivery in less than 5 minutes is essential to prevent asphyxia as a consequence of compression of the umbilical cord, compression of the carotid vessels and potential premature separation of the placenta.

Morbidity with shoulder dystocia

Fetal mortality and morbidity rates are significant. There is a linear decline in cord arterial pH with increasing time to delivery. Although the incidence of devastating hypoxic–ischaemic encephalopathy as a consequence of asphyxia is low, it can be minimized when the head-to-body delivery time is less than 5 minutes [10]. Brachial plexus injuries result from lateral traction on the fetal head during delivery. Erb’s palsy is caused by damage to the C5 and C6 nerve roots, with paralysis of the deltoid and short muscles of the shoulder and of brachialis and biceps which flex and supinate the elbow. The arm hangs limply by the side with the forearm pronated and the palm facing backwards (‘waiter’s tip position’). Around 90% of these lesions recover fully or almost fully. Fractures of the clavicle and humerus can occur which heal with conservative treatment without permanent sequelae.

Maternal consequences of shoulder dystocia include postpartum haemorrhage, uterine rupture and third and fourth degree vaginal lacerations [11].

Treatment of shoulder dystocia

McRobert’s manoeuvre involves placing the mother’s hips in hyperflexion against the abdomen, while being slightly abducted and externally rotated in an effort to widen the pelvic diameter. This should be the initial manoeuvre performed as it is successful in reducing up to 40% of cases [11].

The addition of downward suprapubic pressure applied just proximal to the symphysis by an assistant – either continuously or in a rocking motion – may also be successful and is commonly used in association with McRobert’s manoeuvre. Suprapubic pressure adducts the shoulders and disimpacts the baby from the pubic symphysis into an oblique position. These two manoeuvres result in successful shoulder delivery in over 50% of episodes.

Additional manoeuvres include the Wood’s corkscrew and the Rubin II manoeuvres, which seek to rotate the shoulder girdle into a different orientation and free the anterior shoulder from under the symphysis pubis. Both these rotational manoeuvres require the physician’s hands to be placed into the vagina and a large episiotomy.

Further alternatives include placing the mother ‘on all fours’ in a hands and knees position, which can facilitate spontaneous delivery. Zavanelli’s manoeuvre involves replacing the head in the birth canal and proceeding to immediate emergency caesarian section.

Postpartum haemorrhage

Primary postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is defined as excessive bleeding in the first 24 hours after birth, which is diagnosed clinically as excessive bleeding making the patient symptomatic with lightheadedness, vertigo and syncope. Or it results in signs of maternal hypovolaemia with hypotension, tachycardia and oliguria [12]. Blood loss is frequently underestimated, with usual losses at vaginal delivery being under 500 mL.

Other definitions of PPH include blood loss in excess of 500 mL after vaginal birth, or>1000 mL after caesarean section. Severe PPH is blood loss greater than or equal to 1000 mL while a critical or major PPH is blood loss of greater than 2500 mL.

The common causes of PPH are referred to as the ‘four Ts’, which in order of decreasing frequency include:

laceration of the cervix, vagina and perineum

laceration of the cervix, vagina and perineum

non-genital tract (e.g. subcapsular liver rupture)

non-genital tract (e.g. subcapsular liver rupture)

retained products, placenta (cotyledon or succenturiate lobe), membranes or clots, abnormal placenta

retained products, placenta (cotyledon or succenturiate lobe), membranes or clots, abnormal placenta

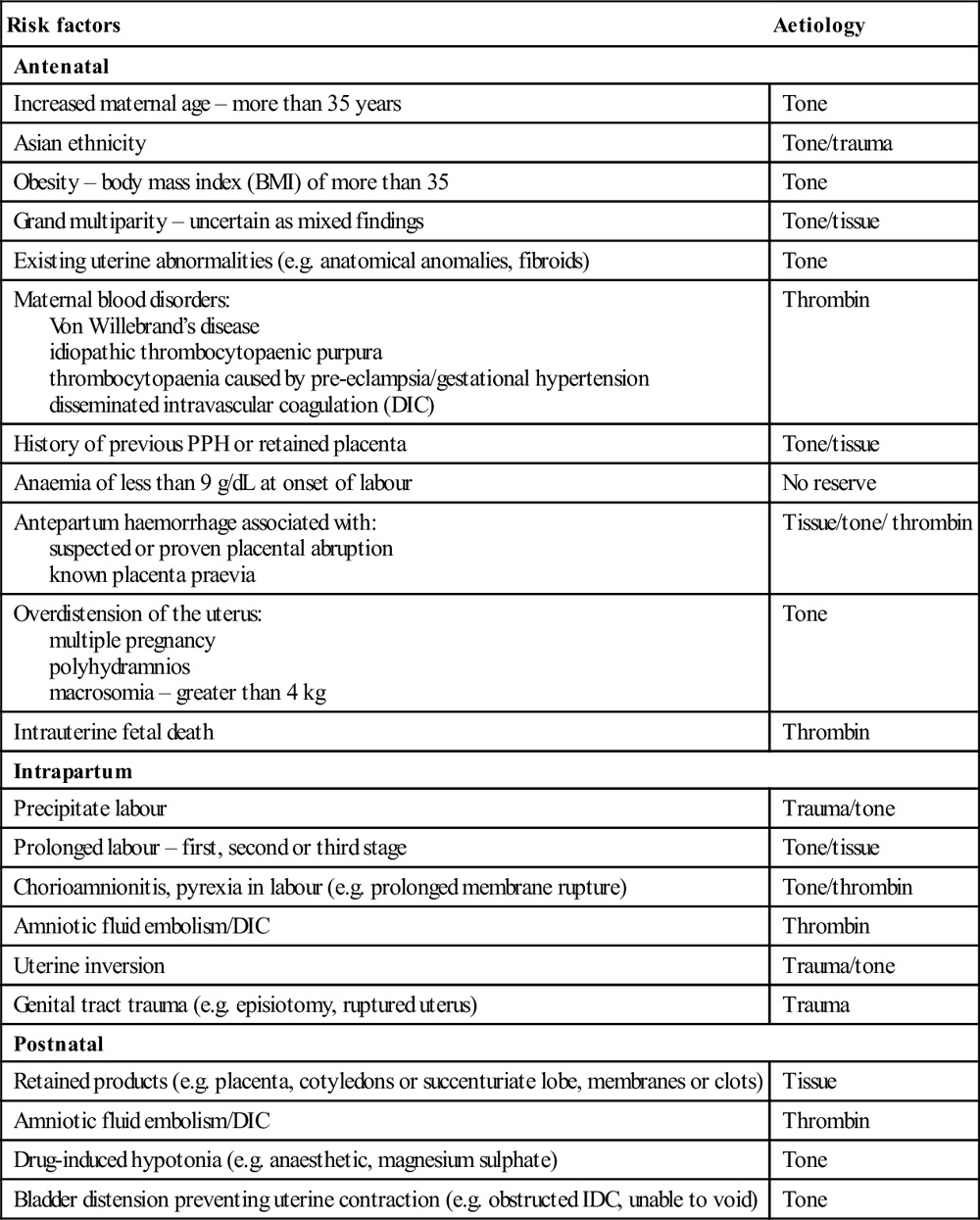

Table 19.1.2

| Risk factors | Aetiology |

| Antenatal | |

| Increased maternal age – more than 35 years | Tone |

| Asian ethnicity | Tone/trauma |

| Obesity – body mass index (BMI) of more than 35 | Tone |

| Grand multiparity – uncertain as mixed findings | Tone/tissue |

| Existing uterine abnormalities (e.g. anatomical anomalies, fibroids) | Tone |

| Maternal blood disorders: Von Willebrand’s disease idiopathic thrombocytopaenic purpura thrombocytopaenia caused by pre-eclampsia/gestational hypertension disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) |

Thrombin |

| History of previous PPH or retained placenta | Tone/tissue |

| Anaemia of less than 9 g/dL at onset of labour | No reserve |

| Antepartum haemorrhage associated with: suspected or proven placental abruption known placenta praevia |

Tissue/tone/ thrombin |

| Overdistension of the uterus: multiple pregnancy polyhydramnios macrosomia – greater than 4 kg |

Tone |

| Intrauterine fetal death | Thrombin |

| Intrapartum | |

| Precipitate labour | Trauma/tone |

| Prolonged labour – first, second or third stage | Tone/tissue |

| Chorioamnionitis, pyrexia in labour (e.g. prolonged membrane rupture) | Tone/thrombin |

| Amniotic fluid embolism/DIC | Thrombin |

| Uterine inversion | Trauma/tone |

| Genital tract trauma (e.g. episiotomy, ruptured uterus) | Trauma |

| Postnatal | |

| Retained products (e.g. placenta, cotyledons or succenturiate lobe, membranes or clots) | Tissue |

| Amniotic fluid embolism/DIC | Thrombin |

| Drug-induced hypotonia (e.g. anaesthetic, magnesium sulphate) | Tone |

| Bladder distension preventing uterine contraction (e.g. obstructed IDC, unable to void) | Tone |

Adapted from Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guideline: PPH, with permission from the Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guidelines Program.

Management of PPH

Prevention is essential by identifying the at-risk patient and the aggressive use of oxytocin, along with active management of the third stage of labour. These measures reduce the incidence of PPH by 40%. The initial response to PPH requires a multidisciplinary team approach to restore the woman’s haemodynamic state while simultaneously identifying and treating the cause of bleeding.

Resuscitate with intravenous fluids and cross-match blood, carefully estimating the amount of blood loss including blood-soaked linen and dressings. O negative may be required followed by cross-matched blood. Fresh frozen plasma (FFP), platelets and cryoprecipitate may all be indicated in severe postpartum haemorrhage, with initiation of the department’s Massive Transfusion Protocol. Currently, there is no evidence or consensus to guide the optimal ratio of blood component replacement in obstetric haemorrhage, although most use similar ratios as for trauma (1:1:1 for RBC:FFP:platelets) [12]. Consultation with a haematologist is important and the use of tranexamic acid or recombinant activated Factor VII considered.

Before massaging the fundus, ensure that the placenta has been delivered and is complete. An adherent or incomplete placenta in the setting of postpartum haemorrhage may necessitate transfer to the operating suite for operative removal. If the placenta is delivered and complete, check that the third stage oxytocic has been given and massage the uterine fundus to promote contraction. Expel any uterine blood clots and ensure the bladder is empty.

Ensure a careful inspection of the vagina, cervix and perineum is made to confirm or exclude genital trauma as a cause of ongoing bleeding. Clamp obvious arterial vessels and repair lacerations. Transfer to an operating suite may be necessary to allow a full inspection of the vagina, cervix and uterus and effective repair. Suspect uterine rupture in a patient with severe abdominal pain.

Uterine atony

If uterine atony is causal, give oxytocin 5 units IV followed by an infusion of 20–40 units oxytocin in 1 L of 0.9% saline. Use an initial rate of 250 mL/h with the rate slowed as uterine contraction occurs. Other drugs used for uterine atony include misoprostol 800–1000 μg per rectum (PR) and/or ergometrine 250 μg by the intravenous or intramuscular route. Persisting uterine atony necessitates immediate transfer to theatre to identify and remove retained products; bimanual uterine compression may be employed as a temporizing measure.

Second line drugs, such as PGF2-α 250 μg IM or intramyometrially may be used up to a maximum of 2 mg, which is successful in 60–85% cases of refractory uterine atony. Side effects include nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, pyrexia, hypertension and bronchoconstriction. Its use is therefore contraindicated in women with asthma and hypertension.

Coagulopathy

Coagulopathies must be considered and blood sent for full blood count, clotting studies, including serum fibrinogen, and baseline electrolytes and renal and liver function tests. If a coagulation or platelet defect is present correct with either FFP or platelets.

Other surgical causes

Continuing severe postpartum haemorrhage and haemodynamic instability after management of all of reversible causes requires urgent theatre with possible laparotomy. Causes include uterine rupture or inversion and persistent atony; or causes such as subcapsular liver rupture or amniotic fluid embolism. Surgical procedures for intractable bleeding include placement of B-Lynch compression suture to the uterus, bilateral uterine artery ligation and hysterectomy [12].

Neonatal resuscitation

Approximately 10% of infants require some assistance to begin breathing at birth, although less than 1% require extensive resuscitation. Of those requiring some assistance, the majority simply require basic manoeuvres, such as stimulation, airway positioning and transient mask ventilation. Few require intubation and ventilation, with the need for chest compressions and medications uncommon [13].

The need for resuscitation may be completely unexpected and so prior preparation to manage a newborn requiring resuscitation is essential. This includes suitable equipment and training and an appropriate location to conduct resuscitation. Early contact is made with the neonatal or paediatric team to plan for transfer or retrieval.

Neonates in need of resuscitation

The need for resuscitation in the newborn is more likely in circumstances such as preterm birth, absent or minimal antenatal care, maternal illness, complicated or prolonged delivery, antepartum haemorrhage, multiple births, previous neonatal death and a precipitate birth. This suggests that all emergency department deliveries should be treated as possibly high risk, with appropriate preparations made to provide neonatal resuscitation.

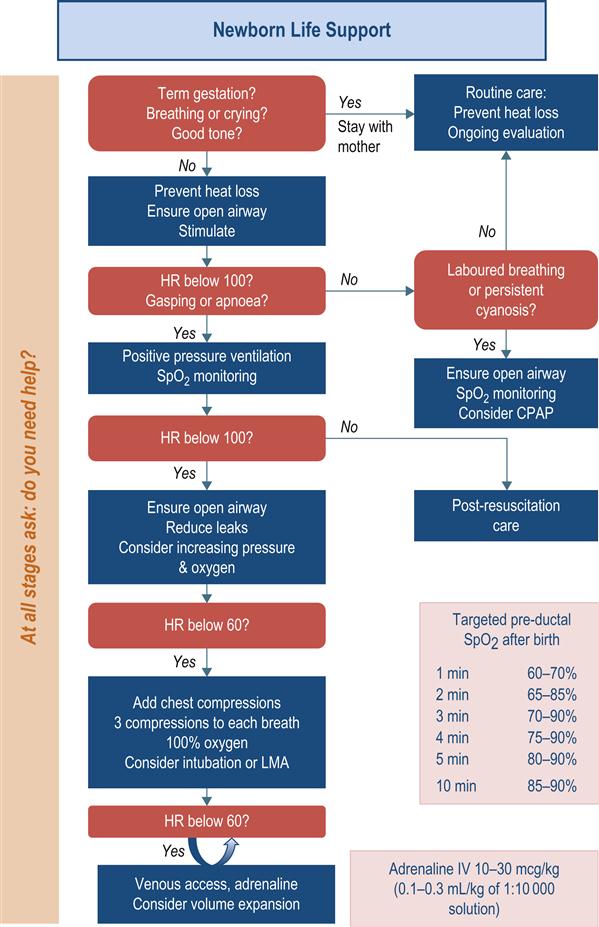

Assessment and resuscitation of the newborn

The initial assessment should focus on tone, breathing and heart rate while subsequent assessment during resuscitation is based on the infant’s heart rate, breathing, tone and oxygenation. The Australian Resuscitation Council Neonatal Resuscitation Flowchart illustrates the assessment and resuscitation of a newborn baby (Fig. 19.1.1).

Infants who are born at term, have had low or no risk factors for needing resuscitation, are breathing or crying and have good tone should be dried and kept warm. These actions can be provided on the mother’s chest and do not require separation of mother and baby. Poor tone and minimal response should be managed with brisk but gentle drying with a soft towel to stimulate the infant to breathe.

Positive-pressure ventilation

If the infant remains apnoeic or breathing is inadequate, positive-pressure ventilation is started using a self-inflating bag, T-piece device or a flow-inflating bag via a face mask or even endotracheal tube. Persistent apnoea, particularly associated with hypotonia and a heart rate<100/min is an ominous sign. The main measure of effectiveness of ventilation is prompt sustained improvement in heart rate. This can be determined by listening to the heart with a stethoscope or initially by feeling for pulsations at the base of the umbilical cord. It should be consistently above 100/min within 1 minute of birth in a non-compromised infant. Rates<100/min are managed with ventilation, while a rate<60/min requires both positive pressure ventilation and chest compressions.

Chest compressions

The preferred technique for chest compression is an ‘encircling technique’ with two thumbs on the lower third of the sternum, with the fingers surrounding the thorax to support the back. A chest compression should be performed each half second with a half second pause after each third compression to deliver a breath, resulting in a 3:1 ratio with a total of 90 compressions and 30 breaths per minute [13].

Oxygenation

Oxygenation is assessed using pulse oximetry, noting that the healthy term newborn takes up to 10 minutes to achieve oxygen saturations of 85–90%. While insufficient oxygenation can impair organ function or cause permanent injury, there is increasing evidence that even brief exposure to excessive oxygenation is harmful to the newborn during and after resuscitation. Emergency physicians should recognize this aspect of a newborn’s normal respiratory physiology and not provide high dose oxygen in an attempt to attain unnecessarily high oxygen saturations. A guide to expected oxygenation saturations in the first 10 minutes after birth is listed on the Australian Resuscitation Council Neonatal Resuscitation Flowchart (see Fig. 19.1.1).

Air should be given initially for ventilation of the term infant while pulse oximetry is commenced. Supplemental oxygen delivered by a blender with air is used when the infant’s oxygen saturations do not reach the lower end of the target saturations despite effective ventilation. Increased concentrations of oxygen should be used if the infant’s heart rate fails to increase or oxygenation as measured by oximetry remains lower than expected.

Attempting to increase the oxygen saturation over 90% in a newborn is potentially harmful. In all cases, the first priority is to ensure adequate inflation of the lungs followed by increasing the concentration of inspired oxygen only if needed [13].

Adrenaline

Adrenaline is recommended if the heart rate remains<60 beats/min after 1 minute of effective ventilation and chest compressions. The recommended intravenous adrenaline dose is 10–30 μg/kg (0.1–0.3 mL/kg of a 1:10 000 adrenaline solution) followed by a small saline flush. This dose is repeated if the heart rate remains below 60 beats/min despite effective ventilation and cardiac compressions. Higher doses of adrenaline are not recommended.

The preferred route of administration of adrenaline is via the umbilical vein. Other routes include an intraosseous catheter or peripheral vein catheter, although these are more technically challenging in the newborn. Adrenaline can also be administered via the endotracheal tube, although there is little evidence to support this route [8]. If the endotracheal route is used, a dose of 50–100 μg/kg (0.5–1 mL/kg of a 1:10 000 solution) is recommended.

Intravenous fluids

Consider intravenous fluids when there is suspected blood loss and/or the infant appears shocked (pale, with poor perfusion and a weak pulse) and has not responded adequately to the other resuscitative measures outlined above. Normal saline is used initially in a dose of 10 mL/kg, but blood may be required early in the setting of blood loss. In the absence of a history of blood loss, give a single dose of fluids to an infant who fails to respond adequately to chest compressions, adrenaline and ventilation; repeated doses are not indicated.

Naloxone

Naloxone is not used routinely as part of the initial resuscitation of newborns with respiratory depression in the delivery room. It may be considered in continuing respiratory depression following restoration of heart rate and colour by standard resuscitation methods as outlined above. The current recommended naloxone dose is 0.1 mg/kg intravenously or intramuscularly, though evidence to support this recommendation is lacking [8].

Meconium-stained liquor

Meconium-stained liquor (light green tinge) is relatively common, occurring in up to 10% of births. Notwithstanding this, meconium aspiration is a rare event and has usually occurred in utero before delivery. Suctioning the infant’s mouth and pharynx before the delivery of the shoulders makes no difference to the outcome of babies with meconium-stained liquor and is not recommended. Similarly, routine endotracheal suctioning of babies with meconium-stained liquor who are vigorous (breathing or crying, good muscle tone) is discouraged, as it does not alter their outcome and may cause harm.

In the non-vigorous baby with depressed vital signs, there is no clear evidence to support or refute the practice of endotracheal suctioning which is frequently performed. It must not delay other critical resuscitative measures and, if tracheal suction is performed, it must be accomplished before spontaneous or assisted respirations are commenced to minimize delay in establishing breathing. Endotracheal suctioning of meconium is achieved via an endotracheal tube which is then removed. There is no need to repeat this intervention and efforts should be then directed to establishing respiration [3].

Neonatal transfer

Neonates requiring resuscitation following emergency delivery will need to be referred to a regional or tertiary neonatal unit for ongoing care. Transfer of these babies requires careful communication and coordination between the two centres, with transport usually undertaken by a specialized neonatal transport team.

19.2 Ectopic pregnancy and bleeding in early pregnancy

Sheila Bryan

Introduction

Bleeding in early pregnancy is a common problem affecting approximately 25% of all clinically diagnosed pregnancies and, of these, approximately 50% will have bleeding due to a failed pregnancy [1]. Other causes of bleeding include ectopic pregnancy and molar pregnancy; however, most bleeding is incidental or physiological and has no bearing on the outcome of the pregnancy.

Terminology

The terminolgy used to describe early pregnancy bleeding conditions is defined below:

Miscarriage

A miscarriage is defined as pregnancy loss occurring before 20 completed weeks’ gestation or a fetus less than 400 g weight, if the gestation is unknown.

Threatened miscarriage

A threatened miscarriage is any vaginal bleeding other than spotting before 20 weeks’ gestation.

Inevitable miscarriage

Inevitable miscarriage is a miscarriage that is imminent or in the process of happening.

Complete miscarriage

A complete miscarriage is when all products of conception have been expelled.

Failed pregnancy

A failed pregnancy is defined on ultrasound criteria. These include the finding of a crown rump length (CRL) greater than 6–10 mm with no cardiac activity or a gestational sac equal to or greater than 20–25 mm with no fetal pole (previously referred to as an anembryonic pregnancy or a blighted ovum).

A failed pregnancy may then remain in the uterus (previously termed a missed abortion) or may progress to either an incomplete or complete miscarriage, as defined by the presence or absence of pregnancy-related tissue in the uterus.

Pregnancy of unknown location

A pregnancy of unknown location refers to the situation where the beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotrophin (β-hCG) is elevated, but no pregnancy can be identified on ultrasound.

Ectopic pregnancy

An ectopic pregnancy is a pregnancy that is implanted outside of the normal uterine cavity. The most common location for an ectopic pregnancy is in the fallopian tube. Other sites include cervix (≈1%), ovary (1–3%), interstitial (1–3%), abdomen (1%) and, rarely, in a uterine scar.

The natural history of an ectopic pregnancy may be one of resorption, spontaneous miscarriage (vaginal or tubal) or it may continue to grow and disrupt the surrounding structures (rupture).

History

History should include the date of the last normal menstrual period (LNMP) and a complete obstetric and gynaecological history including the use of assisted reproductive technology (ART). Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy include a past history of tubal damage, a previous ectopic pregnancy, pelvic infection, tubal surgery, assisted reproductive technology, increased age, smoking and progesterone-only contraception. Also intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUD) not only decrease the chance of intrauterine pregnancies, but increase the likelihood of an ectopic pregnancy [2].

When estimating the amount of vaginal bleeding, it is useful to quantify the blood loss compared to the woman’s normal menstrual loss. Heavy bleeding and the passage of clots are more common with failed intrauterine pregnancy, as ectopic pregnancy is rarely associated with heavy bleeding.

However, the history of passage of fetal products should not be used as the basis for diagnosis of a miscarriage. Blood clots or a decidual cast may be misinterpreted as the products of conception. In addition, the correct identification of the products of conception does not exclude the possibility of a live twin or of a coexistent ectopic pregnancy (known as a heterotopic pregnancy).

Examination

Determination of the patient’s haemodynamic status and the rate of ongoing bleeding are a priority. Hypotension, tachycardia and signs of peritoneal irritation suggest a ruptured ectopic pregnancy or bleeding from a corpus luteal cyst.

Bimanual examination can localize tenderness and identify adnexal masses and can also give an estimate of the size of the uterus. However, bimanual examination lacks sensitivity and specificity in identification of a small, unruptured ectopic pregnancy [3] and gives no information about the viability of the pregnancy. Speculum examination allows visualization of the vaginal walls and the cervix and allows identification of the source of bleeding.

A complete physical examination should be performed, including assessment of the woman’s mental state, as pregnancy loss may have a profound psychological impact on some women.

Investigations

Biochemistry

Beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotrophin

The beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotrophin (β-hCG) is produced by the outer layer of cells of the gestational sac (the syncytiotrophoblast) and may be detected as early as 9 days after fertilization [4]. The β-hCG level increases by approximately 1.66 times every 48 hours, then plateaus, before falling at around 12 weeks to a lower level.

At any stage of the pregnancy there is always a large range of normal values and a single value cannot be used to determine the location or viability of the pregnancy. There is also potentially significant laboratory-to-laboratory variation and, as such, serial hormone levels may only be compared if they are from the same laboratory.

The half-life of β-hCG is approximately 48 hours, which results in the β-hCG level remaining elevated for a number of weeks post-miscarriage or termination. Therefore, a positive pregnancy test or a single β-hCG level is unreliable to confirm ongoing pregnancy and cannot be used to identify retained products of conception. High levels of β-hCG may be associated with multiple or molar pregnancies.

Urine pregnancy test

Urine pregnancy tests are sensitive to a β-hCG level of 25–60 IU/L. Thus false negatives may rarely occur in the setting of early pregnancy or dilute urine.

Haematology

A full blood count and cross-match should be arranged for haemodynamically unstable patients. Blood group and Rhesus factor should be determined on all patients.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound should be performed in every patient to identify the anatomical location of the pregnancy and to assess fetal viability. The introduction of emergency department (ED) ultrasound provides a cost-effective method for the assessment of a patient presenting with bleeding in early pregnancy [5].

Transvaginal ultrasound

A gestational sac can be identified as early as 31 days’ gestation using transvaginal ultrasound. A yolk sac can be identified within the gestational sac at 5–6 weeks when the β-hCG is around 1500 IU/L (except in the case of anembryonic pregnancy). Embryonic cardiac activity should be identified by approximately 39 days’ (5.5 weeks’) gestation, at which stage the crown rump length of the embryo is approximately 5 mm [6].

Transabominal ultrasound

The findings on transabominal ultrasound are similar approximately 1 week later. Previously a β-hCG of approximately 1500 IU was called the discriminatory zone, meaning that if no pregnancy was identified in the uterus at this level, then an ectopic pregnany could be diagnosed. However, ultrasound is still valuable even when the β-hCG level is less then 1000 IU/L, as direct or indirect signs of an ectopic pregnancy can often be found at levels lower than 1500 IU [7].

The two most common errors in the interpretation of early pregnancy ultrasound include the misidentification of a pseudo-sac or an endometrial cyst as an early gestational sac. A pseudo-sac is a small collection of fluid seen in the uterine cavity, often in association with an ectopic pregnancy. Secondly, assuming that an ultrasound finding of a uterus with no signs of pregnancy is a complete miscarriage, rather than correctly identifying the situation as that of a pregnancy of unknown location. One study of 152 women with a history and examination supporting a complete miscarriage had a 6% rate of ectopic pregnancy.

Heterotopic pregnancy

Identification of an interuterine pregnancy does not exclude a coexistent ectopic (heterotopic) pregnancy. The incidence of heterotopic pregnancy in the general population is around 1:3889 but, in patients who have undergone assisted reproductive technology (ART), the incidence is as high as 1:100–1:500 [8]. Thus, in the patient with risk factors and clinical features of an ectopic pregnancy, finding an intrauterine gestation cannot rule out a coexistent ectopic.

Management

Rh(D) immunoglobulin

All patients should have their blood group and Rhesus (Rh) factor determined. As little as 0.1 mL of Rh(D) positive fetal blood will cause maternal Rh iso-immunization. A dose of 250 IU Rh(D) immunoglobulin is given as soon as possible in early pregnancy bleeding with a singleton pregnancy to an Rh-negative woman, certainly within 72 hours of onset of the bleeding. This dose prevents immunization from a feto-maternal haemorrhage of up to 2.5 mL of fetal cells. Further doses may be required in repeat or prolonged bleeding [9].

A dose of 625 IU Rh(D) is recommended in multiple pregnancies or with a gestation of greater than 13 weeks. The Kleihauer test is used in later pregnancy to quantify the amount of fetal cells in the maternal circulation, but is unreliable in early pregnancy.

Note that international guidelines on the use of Rh(D) immunoglobulin differ, such that in the UK no anti-D Ig is required for spontaneous miscarriage before 12 weeks gestation, provided there is no instrumentation of the uterus.

Ectopic pregnancy

Haemodynamically unstable patient

A haemodynamically unstable patient with suspected ectopic pregnancy should be resuscitated and referred for surgical intervention. A ruptured corpus luteal cyst may rarely cause similar haemodynamic compromise and is also diagnosed at laparoscopy.

Haemodynamically stable patient

The management options for a haemodynamically stable patient with an ectopic pregnancy found on ultrasound include observation, medical treatment or surgical intervention.

Factors to be considered in reaching a management decision include the location of the ectopic pregnancy, the β-hCG level, the size of the ectopic pregnancy, the presence of fetal cardiac activity and patient factors.

Selection criteria for conservative or medical management depend upon the gynaecological team, but may include stable patients with a low β-hCG (<1000 IU/L) which is falling, non-tubal ectopic pregnancy or a small tubal ectopic pregnancy (<3 cm) with no cardiac activity and a β-hCG level less than 5000 IU/L [10].

Miscarriage

Haemodynamically unstable patient

Any patient with heavy vaginal bleeding, hypotension and bradycardia should have an immediate speculum examination as, occasionally, the products of conception cause dilatation of the cervix, which leads to cervical shock, a form of neurocardiogenic shock. Removal of the clot and products of conception from the cervix usually results in cessation of bleeding and reversal of the shock.

Haemodynamic compromise may also be secondary to significant blood loss related to the miscarriage. Fluid resuscitation should be instituted simultaneously with attempts to control the bleeding by removal of blood clot and the products of conception from the cervix and vagina. Uterine contraction may be induced by administering ergometrine 200 micrograms IM if removal of clot and tissue fail to control the bleeding. Emergency surgical evacuation of the uterus is then required.

Haemodynamically stable patient

A haemodynamically stable patient has traditionally been treated by surgical evacuation of uterine contents following the diagnosis of a miscarriage. There have been a number of systematic reviews comparing conservative management with surgical or medical managment (such as prostaglandin E1) [11,12]. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to support the superiority of any one of these three treatment options. Although studies have assessed the time to achieve complete miscarriage and the frequency of complications, they suffer from different inclusion criteria and duration of conservative management.

The success of conservative treatment is variable, but 78.6% of women in one study had an empty uterus at 8 weeks [13]. Conservative management is usually associated with slightly longer duration of bleeding and pain and possibly the need for transfusion. The incidence of infection was similar or higher in the surgical group. Complications of surgery, such as cervical trauma, uterine perforation and intrauterine adhesions, were uncommon.

Currently, the view is that the woman’s preference should be the major consideration in recommending a treatment option and the haemodynamically stable patient may be discharged for ongoing care by the gynaecology team [11]. Discharge advice should include explicit indications of when to return, such as heavy bleeding or signs of infection, and advice regarding pelvic rest and a clear follow-up plan.

Prognosis

Approximately 50% of patients with bleeding in early pregnancy will proceed to term. Only 60% of women with an ectopic pregnancy will conceive again naturally, and will have a recurrent ectopic rate of 25–30% in subsequent pregnancies.

Disposition

Patients with a threatened miscarriage and an ultrasound confirming a live intrauterine gestation have an 85–90% chance of the pregnancy progressing to term. Poor prognostic indicators include advanced maternal age, ultrasound findings of an enlarged yolk sac and fetal bradycardia after 7 weeks’ gestation. Patients should be advised to avoid sexual intercourse and not to use tampons until after the bleeding has settled. There is no evidence to support improved pregnancy outcomes from recommending bed rest [14]. Referral for counselling or psychological support may be indicated in some women.

Investigation for an underlying cause is generally not indicated until after a third consecutive miscarriage. These include anatomical uterine abnormalities, thrombophilic disorders such as antiphospholipid syndrome and Factor V Leiden, chromosomal abnormalities, immune disorders, hormonal disorders, infection and environmental and lifestyle factors.

Patients with a non-viable intrauterine pregnancy or an ectopic pregnancy are referred to a gynaecology service for ongoing management.

19.3 Bleeding after the first trimester of pregnancy

Jenny Dowd and Sheila Bryan

Introduction

Vaginal bleeding after the first trimester may be due to a number of causes. The most common is classified as ‘incidental’, where the bleeding is not directly related to pregnancy.

Antepartum haemorrhage

Bleeding that occurs after 20 weeks’ gestation is classified as an antepartum haemorrhage (APH). Obstetric causes of bleeding include placenta praevia, accidental haemorrhage or placental abruption and vasa praevia. Various amounts of blood loss from 60 to 200 mL have been used as a definition threshold for an APH but, in practice, any bleeding beyond minor spotting should be assessed.

Postpartum haemorrhage

Primary post-partum haemorrhage (PPH) is defined as heavy (>500 mL) vaginal bleeding within 24 hours of delivery and is discussed in Chapter 19.1.

Secondary postpartum haemorrhage

Secondary PPH is most commonly due to infection and/or retained tissue and may cause significant bleeding up to 6 weeks’ postpartum.

Antepartum haemorrhage

Differential diagnosis

Incidental causes

These include bleeding from the lower genital tract, most commonly from physiological cervical erosion or ectropion, where the bleeding may be either spontaneous or post-traumatic, such as post-coital. Other causes that need to be excluded include bleeding from cervical polyps, cervical malignancy and cervical or vaginal infection.

Bleeding from haemorrhoids or vulval varices may also be mistakenly reported as vaginal bleeding.

Placenta praevia

Placenta praevia occurs when the placenta is situated in the lower part of the uterus and therefore is in front of the presenting part of the fetus. It occurs in 0.5% of pregnancies [1]. Bleeding in this situation is usually painless, unless associated with labour contractions and often presents with several small, ‘warning’ bleeds.

Accidental haemorrhage (marginal bleed or placental abruption)

This is bleeding from a normally situated placenta. It may come from the edge of the placenta, known as a marginal bleed, or from behind the placenta associated with placental separation (placental abruption). Vaginal bleeding may not always be present with a placental abruption, but it is usually associated with pain. A placental abruption that causes significant detachment of the placenta may cause fetal compromise and fetal death in up to 30% of cases [2].

The retroplacental clot consists of maternal blood with up to 2–4 L being concealed behind the placenta without vaginal loss. A placental abruption may follow relatively minor blunt trauma, such as a fall onto the abdomen, or a shearing force, such as that applied in a motor vehicle deceleration crash. Placental abruption may also occur spontaneously associated with hypertension, inherited disorders of coagulation or with cocaine use [3].

Vasa praevia

This is the presence of fetal vessels running in the amniotic membranes distant from the placental mass and across the cervical os, such as with a succinturate lobe of placenta or a villamentous insertion of the cord, so that an earlier ultrasound may have described a fundal placenta. These vessels occasionally rupture, often in association with rupture of the amniotic membranes.

When this happens, the bleeding is from the fetus, which may quickly lead to fetal compromise. The first indication of this may be fetal bradycardia or other abnormalities of the fetal heart rate seen on cardiotocographic (CTG) tracing.

Physiological

Vaginal blood mixed with mucus is called a ‘show’ and is due to the mucus plug or operculum within the endocervical canal dislodging as the cervix begins to dilate. This usually occurs at the time of, or within a few days of, the onset of labour and is not significant unless the pregnancy is preterm or associated with rupture of the membranes. As a general guide, when a woman needs to wear a pad to soak up blood, she should be assessed as having an APH.

History

The history should specifically include details of recent abdominal trauma or drug use suggesting a diagnosis of placental abruption. A history of recent coitus is commonly identified in bleeding from a cervical ectropion. The history should also include details regarding the presence and quality of fetal movements.

Constant pain over the uterus or sometimes in the lower back from separation of a posteriorly situated placenta is suggestive of a placental abruption. Intermittent pains in the lower abdomen or back may represent uterine contractions. Women may describe this as ‘period pains’ or tightenings and may notice a general hardening over the whole uterus in association with the pain. Painless bleeding is suggestive of either an incidental cause or of placenta praevia.

An increase in pelvic pressure associated with a mucous vaginal fluid loss and spotting or mild bleeding suggests cervical incompetence. This usually presents between 14 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Prior cervical damage secondary to either a cone biopsy or a cervical tear is a risk factor for cervical incompetence.

Examination

Assess the mother as a priority. A relatively low blood pressure with a systolic of 90 mmHg and a resting tachycardia of up to 100 bpm is normal in pregnancy.

Examination after 30 weeks’ gestation should be performed with the right hip elevated by a pillow to give a 15° tilt of the pelvis to the left. This avoids the problem of vena caval compression (supine hypotension syndrome) from pressure of the gravid uterus reducing inferior vena caval venous return.

Speculum or digital vaginal examination

Speculum or digital vaginal examination should never be performed until the site of the placenta is determined by ultrasound, to avoid disrupting a low-lying placenta and precipitating torrential haemorrhage.

Once an ultrasound scan has excluded a low-lying placenta, an experienced operator may proceed to a speculum examination to look for liquor within the vagina in suspected rupture of the membranes, or to assess the cervix to localize the site of bleeding and to look for cervical dilatation.

A sterile speculum examination is indicated, again by an experienced operator, if preterm pre-labour rupture of the membranes is possible, to decrease the risk of introducing infection. Digital vaginal examination should be performed to assess the cervix for dilatation if labour is suspected.

Ideally, a CTG should be applied to assess the status of the fetus beyond 24 weeks’ gestation. Auscultation of the fetal heart for several minutes should be attempted if this is not available. The baseline rate and variations related to contractions are important. The normal range of the fetal heart rate is 120–160 bpm, but a healthy term or post-term fetus may have a heart rate of between 100 and 120 bpm. Decelerations of the fetal heart rate may indicate fetal distress.

Investigations

Laboratory blood tests

Blood should be taken for baseline haemoglobin and platelet count, coagulation screen, Kleihauer test, blood group, Rhesus factor, Rhesus antibodies and a cross-match.

A pre-eclampsia screen should be ordered if the patient is hypertensive, including liver function tests and uric acid as well as the platelet count.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is used to assess fetal gestation, presentation, liquor volume and placental position. Many ‘low-lying’ placentas at 18 weeks are no longer classified as placenta praevia by 30–32 weeks, owing to the differential growth of the lower uterine segment as pregnancy progresses. A placental edge at least 2 cm away from the cervical os at term is considered safe to allow a planned vaginal delivery.

As only 50% of placental abruptions will be seen on ultrasound, it is unreliable for excluding this problem with the diagnosis usually made on clinical grounds alone. Transvaginal ultrasound with an empty bladder is best to visualize the cervix to look for shortening or ‘beaking’ of the amniotic sac into the internal os which are signs of early cervical incompetence.

Management

Incidental causes of bleeding usually require no specific therapy apart from explanation and reassurance. Cervical polyps are rarely removed during pregnancy due to the risk of heavy bleeding.

Minor amounts of bleeding due to placenta praevia distant from term are managed by close observation, usually initially as an inpatient or later as an outpatient.

Small placental abruptions may also be managed conservatively with serial ultrasound scans to monitor fetal growth and regular CTG assessments. Delivery is usually advised round 37 weeks to pre-empt a massive placental abruption developing. Sometimes, a small retroplacental clot will cause weakening of the amniotic membranes and subsequent rupture of the amniotic sac 1–2 weeks after the initial bleed.

Massive antepartum haemorrhage, often with fetal demise when associated with placental separation, requires urgent delivery, possibly by caesarean section. Hypovolaemia and coagulopathies are treated as per usual guidelines.

Prognosis

A decision needs to be made in a hospital where there are no obstetric or neonatal facilities about when to transfer a patient to an obstetric unit. Corticosteroids should be administered to the mother if the fetus is between 23 and 34 weeks and delivery can be delayed for 24 hours. Two intramuscular doses of betamethasone or dexamethasone given over 24 hours decrease the baby’s risk of developing respiratory distress syndrome, necrotizing enterocolitis and intraventricular haemorrhages [4].

There are new national guidelines for the infusion of magnesium sulphate in pregnancies less than 30 weeks’ gestation where delivery within 24 hours is expected. This significantly decreases the rate of subsequent cerebal palsy in such infants [5]. Discussion about dose and timing should be with the obstetric staff receiving the woman if transfer is being planned.

The current survival rate of a baby admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is 40%, 50%, 60% and 70% at 24, 25, 26 and 27 weeks, respectively [4].

Disposition

Discharge home may be appropriate if the diagnosis of a benign physiological cause for bleeding can be made with certainty.

Secondary postpartum haemorrhage

Introduction

Secondary PPH is defined as excessive or prolonged bleeding from 24 hours to 6 weeks’ postpartum. Normal lochia is moderately heavy, red vaginal loss for some days that settles to light bleeding or spotting by 2–4 weeks. Some women have a persistent brownish vaginal discharge for up to 8 weeks [6].

Differential diagnosis

Common causes of secondary PPH

Common causes of secondary PPH include retained products of conception and endometritis. The bleeding is usually prolonged, moderate blood loss or a recurrence of blood loss after an initial decline.

Less common causes of secondary PPH

Less common causes include trophoblastic disease, uterine arterio-venous malformation (AVM) and any of the incidental causes outlined in the previous section. Reactivation of bleeding from an episiotomy or vaginal laceration may also be responsible. Annoying spotting may occur for several weeks in women using progestogen-only contraception, especially when concurrently breastfeeding, in the setting of an oestrogen-deficient endometrium.

History

Distinguishing endometritis from retained products may be difficult clinically and the two conditions often coexist. Endometritis may follow any type of delivery, but is more common in women with a history of prolonged rupture of the membranes and multiple vaginal examinations during labour.

Examination

Abdominal examination may show subinvolution of the uterus with retained tissue, while offensive lochia, uterine tenderness and systemic signs of infection support the diagnosis of endometritis.

An AVM presents with heavy vaginal bleeding and, occasionally, haemodynamic compromise.

Investigations

Full blood examination and two paired sets of blood cultures are indicated if the woman is clinically septic. Send cervical swabs for microscopy and culture and Chlamydia trachomatis detection to help guide the management of endometritis.

Ultrasound is necessary to quantify the amount of retained products of conception and to confirm a diagnosis of an AVM.

Treatment

Empirical treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875 mg/125 mg bd PO for 5–7 days as an outpatient is appropriate if endometritis is suspected but the woman is systemically well. Erythromycin may be substituted in penicillin-sensitive patients. Admit those who are systemically unwell for intravenous antibiotics.

Perform an ultrasound examination if bleeding persists to look for retained products of conception. Patients with small amounts of retained products may be treated conservatively. Uterine curettage in the postpartum period is associated with the risks of uterine perforation or Asherman syndrome due to intrauterine adhesions and/or fibrosis.

19.4 Abnormal vaginal bleeding in the non-pregnant patient

Sheila Bryan and Anthony Brown

Introduction

Vaginal bleeding may be divided into two major categories, bleeding which occurs in a pregnant patient and bleeding in the non-pregnant patient. Therefore, the first step in a patient presenting with vaginal bleeding is to exclude pregnancy. See Chapter 19.2 if the woman is pregnant.

This chapter deals exclusively with bleeding in non-pregnant women. Bleeding may be from the external genitalia, vaginal walls, cervix or uterus. The pathological basis for bleeding from the vulva, vagina and cervix includes infection, trauma, atrophy or malignancy. Uterine bleeding may be physiological or pathological.

Physiological uterine bleeding

Physiological uterine bleeding is associated with ovulatory menstrual cycles, which occur at regular intervals every 21–35 days, and last for 3–7 days. The average volume of blood loss is 30–40 mL with>80 mL being defined as menorrhagia.

The menstrual cycle is controlled by the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) axis. During the first 14 days, oestrogen is produced by the developing follicle, leading to proliferation of the endometrium, which reaches a thickness of 3–5 mm. Oestrogen acts on the pituitary gland to cause the release of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) which result in ovulation. The corpus luteum then releases progesterone in excess of oestrogen.

Progesterone causes stabilization of the endometrium during the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle. In the absence of fertilization, there is involution of the corpus luteum and a fall in oestrogen and progesterone levels. This results in vasoconstriction within the endometrium, which consequently becomes ischaemic and is shed as normal menstrual bleeding.

Pathological uterine bleeding

Pathological causes include infection, structural abnormalities, such as polyps, fibroids, arteriovenous malformations (AVM) or malignancy, drugs, hyperprolactinaemia, coagulopathy and thyroid endocrinopathy. Terms associated with abnormal uterine bleeding are inconsistently defined, but may be broadly considered as abnormal uterine bleeding with ovulatory menstrual cycles and abnormal uterine bleeding with anovulatory menstrual cycles.

Abnormal uterine bleeding with ovulatory menstrual cycles

The most common cause of abnormal uterine bleeding is menorrhagia occurring in ovulatory menstrual cycles. This presents as regular heavy bleeding and may result in anaemia. In these women, the menstrual blood has been shown to have increased fibrinolytic activity and/or increased prostaglandins.

Abnormal uterine bleeding with anovulatory menstrual cycles

Abnormal uterine bleeding or metrorrhagia due to anovulatory menstrual cycles, sometimes referred to as dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB), presents as irregular bleeding of variable volume. In anovulatory menstrual cycles and other high oestrogen states, there is a relative lack of progesterone to oppose the oestrogenic stimulation of the endometrium. This results in excessive proliferation and occasionally hyperplasia/metaplasia of the endometrium. The endometrium also becomes ‘unstable’ and prone to erratic sloughing.

Clinically, this presents as irregular, often heavy, menstrual bleeding. Anovulatory cycles are due to immaturity or disturbance of the normal HPO axis. This is seen at the extremes of reproductive ages in the first decade after menarche and in premenopausal women, as well as in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and during times of either physical or emotional stress.

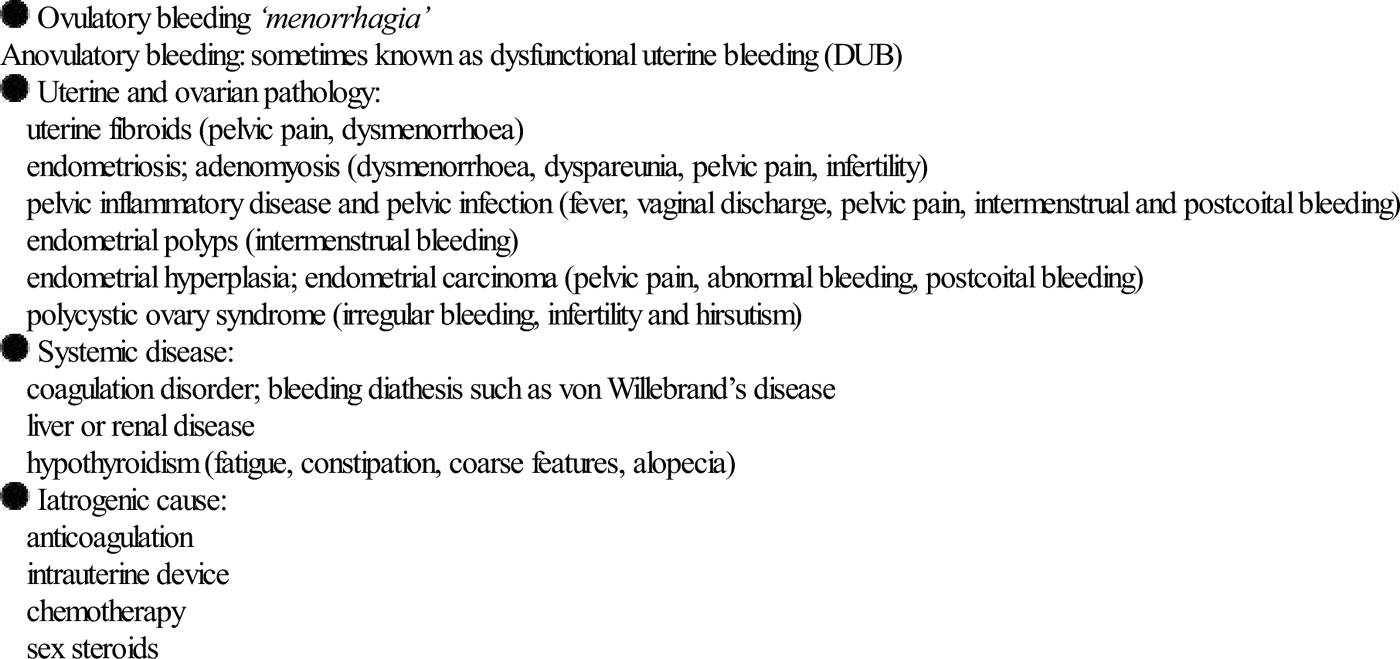

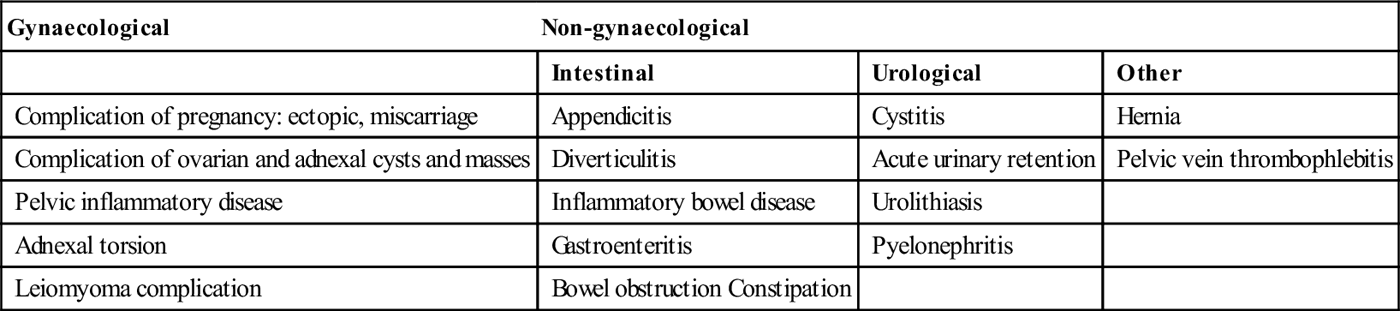

Causes of abnormal vaginal bleeding

It is essential initially to review all the possible causes of vaginal bleeding which may be considered by pathophysiology and/or pathological location (Table 19.4.1).

Table 19.4.1

Differential diagnosis of abnormal vaginal bleeding

History

A careful menstrual history helps determine the cause of the vaginal bleeding. A history of vaginal trauma may indicate vulval or vaginal wall bleeding. The vaginal trauma may be associated with either consensual or non-consensual intercourse or a vaginal foreign body. Exposure in utero to diethyl stilboestrol (DES) should raise suspicion of vaginal malignancy.