History

Focused Clinical Questions and Discussion Points

Question

Discussion

Question

Discussion

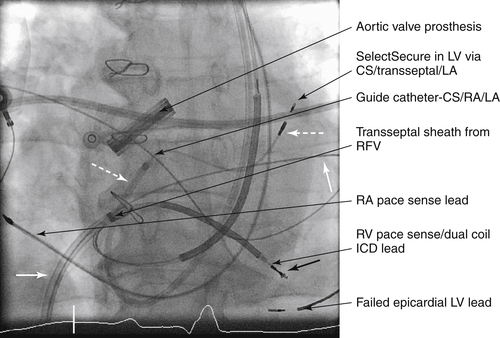

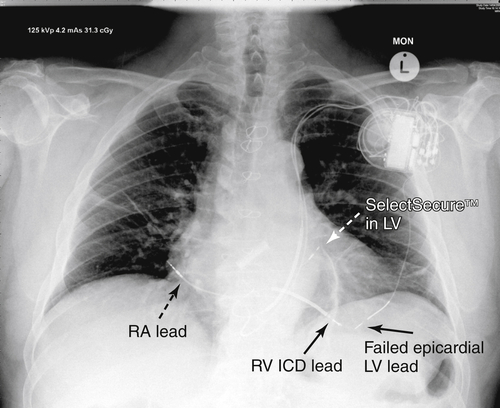

FIGURE 19-1 Left ventricular (LV) endocardial lead on anteroposterior projection. A transseptal sheath was passed from the right femoral vein (RFV) and has dilated the puncture site. Then a steerable guide catheter was passed via the anomalous left superior vena cava, through the enlarged coronary sinus to the right atrium (RA) and maneuvered across the transseptal puncture site into left atrium (LA). Then a Select Secure pacing lead has been passed to the LV via the guide catheter. CS, Coronary sinus; ICD, implantable cardioversion defibrillator.

Question

Discussion

Question

Final Diagnosis

Plan of Action

Intervention

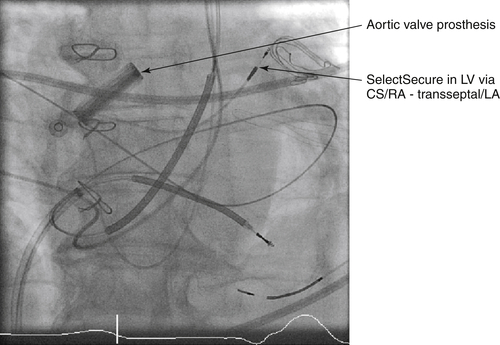

FIGURE 19-2 Anteroposterior projection. The transseptal guide catheter has now been withdrawn, leaving the Select Secure lead in place after fixation. The transseptal catheter remains in place until the end of the procedure to allow for reentry to the left atrium (LA) should there be displacement of the pacing lead as its delivery system is withdrawn. CS, Coronary sinus; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

Outcome

Findings

FIGURE 19-3 Posteroanterior chest radiograph obtained at 24 hours after implantation of the left ventricular (LV) lead. Permanent pacing lead positions are indicated. CS, Coronary sinus; LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium.

Selected References

1. Cazeau S., Alonso C., Jauvert G. et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy. Europace. 2004;5(Suppl 1):S42–S48.

2. Fish J.M., Brugada J., Antzelevitch C. Potential proarrhythmic effects of biventricular pacing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:2340–2347.

3. Garrigue S., Jaïs P., Espil G. et al. Comparison of chronic biventricular pacing between epicardial and endocardial left ventricular stimulation using Doppler tissue imaging in patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:858–862.

4. Morgan J.M., Scott P.A., Turner N.G. et al. Targeted left ventricular endocardial pacing using a steerable introducing guide catheter and active fixation pacing lead. Europace. 2009;11:502–506.

5. Puglisi A., Lunati M., Marullo A.G. et al. Limited thoracotomy as a second choice alternative to transvenous implant for cardiac resynchronisation therapy delivery. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1063–1069.

6. van Gelder B.M., Scheffer M.G., Meijer A. et al. Transseptal endocardial left ventricular pacing: an alternative technique for coronary sinus lead placement in cardiac resynchronization therapy. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:454–460.