Section 18 ENT

18.1 Ears, nose and throat

Foreign body

Management

Removal of a live foreign body

One of the preferred methods is to instil some water for injection from a 10 mL plastic ampoule and leave an examination light on the pinna. The insect swims up to surface towards the light and can be helped to safety by holding the tip of the ampoule.1

There are two techniques used to remove a foreign body. The dry method is by using a Jobson Horne probe for solid objects such as beads or alligator forceps for an insect or a cotton bud. The wet method is by syringing the ear canal with tepid water. The water should be close to body temperature to avoid a caloric effect, which produces nystagmus and vertigo.

Infection

Otitis externa

Infection of the external ear is common and affects between 3 and 10% of the patient population.2 It can be localized (furuncle) or diffuse. The symptoms are pain, itching and tenderness to palpation, followed by aural fullness, hearing loss and discharge. The common pathogens responsible are Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus spp. and Staphylococcus aureus.3

Management

The most important step in the treatment is thorough and atraumatic cleansing of the ear canal.4 Tolerance and cooperation between the patient and the clinician is vital. Pope Otowick (Xomed)® is very useful in the management of this condition. This is a semirigid foam wick that, when inserted into the ear canal, swells, absorbing moisture to increase the size of the ear canal. Topical otic drops, such as Sofradex® (Roussel), are used three to four times a day and the patient is reviewed on a daily basis to change the wick and continue the ear toilet. Occasionally oral antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin or flucloxacillin may be required,5 particularly if there is evidence of cellulitis. The patient is advised to keep the ear clear of any water. Strong analgesics are usually required.

Otitis media

Acute otitis media is a common infection and is due to blocking of the eustachian tube (eustachian catarrh), and negative pressure in the middle ear cavity. Although viral in origin, secondary bacterial infection often supervenes. The most frequently isolated pathogens are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis.6 The symptoms are earache, fullness, hearing loss and fever, with ear discharge if the drum has perforated. The development of discharge usually marks an improvement in the pain and fever.

Otitis media with effusion (glue ear)

This is most common in children in developed countries. The symptoms are fullness and hearing loss, and occasionally pain. Management includes the diagnosis based on history and examination, which reveals a dull, retracted drum or fluid behind the drum without redness. The most reliable sign of a glue ear is an immobile eardrum on valsalva manoeuvre or pneumatic otoscopy. Repeated attacks of glue ear are an indication for the insertion of tympanostomy tubes.

Trauma

Fractured nose

Management

Acute intervention is required in the following circumstances:

Sinusitis

Approximately 90% of upper respiratory infections have associated sinus cavity disease.7 Viral rhinosinusitis is the most common cause and is associated with the common cold. Approximately 0.5–2% of these cases progress to bacterial sinusitis.

Clinical features

Management of viral rhinosinusitis is symptomatic and it is generally self-limiting. Bacterial sinusitis must be treated with antibiotics: amoxicillin, augmentin or keflex could be used as first-line drugs. Although of unproven value, an oral decongestant or antihistamine is commonly used. Complications of sinus disease include meningitis, orbital extension and brain abscess. Diagnosis is by CT scan and treatment is intravenous antibiotics with surgical intervention by an otolaryngologist.

Epistaxis

Nose bleeding is the most common ENT emergency: a Scottish study reported an incidence of 30/100 000 people8 in which the cause could only be found in 15%.9 The common identified causes are trauma, blood dyscrasias, anticoagulation therapy and occasionally hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia.10 Although hypertension has been traditionally labelled as a cause of epistaxis, studies have shown that blood pressure in these patients is no higher than in the control population.11,12

Management

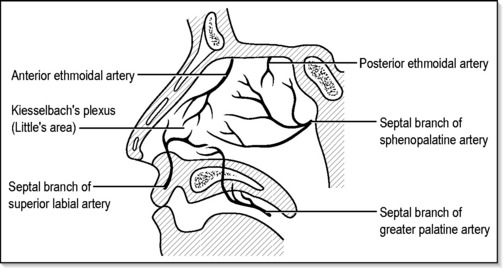

Idiopathic epistaxis, or that due to a local cause such as trauma, can be dealt with using local measures. The most common cause of anterior epistaxis is bleeding from Kiesselbach’s plexus of the septum13 (Fig. 18.1.1), which can easily be controlled by simple measures in the emergency department. Careful examination of a seated patient applying direct pressure to the bleeding vessel by pinching the anterior nares with the thumb and forefinger for up to 10 min will usually slow or cease the bleeding. At this point it is essential to remove all the blood clots from the nasal cavity and the postnasal space using a suction.

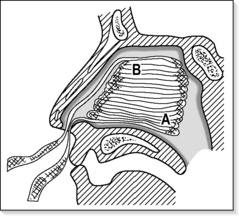

If the bleeding cannot be controlled by the above measures, or the bleeding point is posteriorly placed, the nasal cavity should be packed. There are several ways to pack the nose, the most traditional being to use ribbon gauze to fill the entire nasal cavity in layers (Fig.18.1.2). A Foley urinary catheter can be used to control the posterior bleed, but it can be better controlled with a specifically designed epistaxis catheter such as a Brighton’s epistaxis catheter, which has a double balloon for anterior and posterior tamponade, or a Merocel® nasal pack (Xomed) or Rapid Rhino, which can be used as a nasal tampon, both of which are quite useful. Almost all patients with nasal packing need admission and observation. When the above measures are unsuccessful, further invasive procedures such as postnasal packing, examination under anaesthesia and septal surgery or arterial ligation may be required under general anaesthesia.

THE THROAT

Foreign body

Management

Careful examination of the oropharynx initially, especially if the patient localizes the foreign body above the level of the hyoid and to one side. If the foreign body is found it should be removed under direct vision.

A foreign body at or below the cricopharynx requires general anaesthesia and endoscopy.

Button batteries

Button battery lodged in the oesophagus can cause liquefaction necrosis and perforation so urgent endoscopy and removal is recommended.14

If the battery is lodged past the oesophagus in the stomach most, if not all, will pass in the next 48–72 h and the patient can be safely discharged following reassurance.15

Infection

Infectious mononucleosis (Glandular fever)

The diagnosis is made by abnormal lymphocytes in the blood film and monospot test.

Treatment is symptomatic. Amoxicillin should not be used as it produces a rash.

Post-tonsillectomy bleed

Haemorrhage from the tonsillar fossa that occurs 24 h after tonsillectomy is termed ‘secondary haemorrhage’. This differs from primary, which happens during surgery, and reactionary haemorrhage, which occurs within 24 h of surgery whilst the patient is still in the hospital. The cause of secondary haemorrhage is usually infection and this occurs classically 10 days postoperatively. This incidence is about 1% and is usually not very severe. The management is intravenous antibiotics, usually penicillin. The patient should be admitted and bloods taken for estimation of haemoglobin and cross-matching. Application of a swab soaked in 1 in 1000 adrenaline (epinephrine) to the tonsillar fossa after removal of the clot may help to stop the bleeding. Rarely the patient may need to have a general anaesthetic to cauterize/ligate the bleeder.16

1 Kumar S. An interesting method of removal of live foreign body from the ear. Emerg. Med. 1998;10:278.

2 Bojrab DI, Bruderly T, Razzak YA. Otitis externa. Otolaryngology Clinics of North America. 1996;29(5):761-782.

3 Briggs RJ. Otitis externa: presentation and management. Australian Family Physician. 1995;24(10):1859-1864.

4 Ali Raza S, Denholm SW, Wong JCH. An audit of the management of acute otitis externa in an ENT casualty clinic. Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 1995;109:130-133.

5 Mirza N. Otitis externa – management in the primary care office. Postgraduate Medicine. 1996;99(5):153-158.

6 Block SL. Causative pathogens, antibiotic resistance and therapeutic considerations in acute otitis media. Paediatric Infectious Diseases Journal. 1997;16(4):449-456.

7 Bukata R. Sinusitis, a ubiquitous, yet enigmatic disease. Emergency Medicine and Acute Care Essays. 1997;21(3):1-4.

8 Kotecha B, Fowler S, Harkness P, et al. Management of epistaxis: a national survey. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 1996;78:444-446.

9 Small M, Maran AGD. Epistaxis and arterial ligation. Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 1984;98:281-284.

10 Juselius H. Epistaxis. Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 1974;88:317-327.

11 Shaheen OH. Studies of nasal vasculature and problems of arterial ligation for epistaxis. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 1970;47:30-44.

12 Weiss NS. The relation of high blood pressure to headache and epistaxis and selected other symptoms. New England Journal of Medicine. 1972;287:631-633.

13 Darry KW, Barlow F, Deleyiannis WB, Pinczower EF. Effectiveness of surgical management of epistaxis at a tertiary care center. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:21-24.

14 Gordon AC, Gough MH. Oesophageal perforation after button battery ingestion. Ann Coll Surg Engl. 1993;75:362-364.

15 Kumar S. Management of foreign bodies in the ear, nose and throat. Emergency Medicine. 2004;16:17-20.

16 Evans JNG, editor. Scott Brown’s Otolaryngology, 5th edn. Butterworth, London, 1987, 96.