CHAPTER 18 Delirium

OVERVIEW

Perhaps even more noteworthy is that delirium is a signifier of (often serious) somatic illness.1 Delirium has been associated with increased length of stay in hospitals2 and with an increased cost of care.3,4 Among intensive care unit (ICU) patients prospective studies have noted that delirium occurs in 31% of admissions5; when intubation and mechanical ventilation are required the incidence soars to 81.7%.1

Sometimes, delirium is referred to as an acute confusional state, a toxic-metabolic encephalopathy, or acute brain failure; unquestionably, it is the most frequent cause of agitation in the general hospital. Delirium ranks second only to depression on the list of all psychiatric consultation requests. Given its prevalence and its importance (morbidity and mortality), the American Psychiatric Association issued practice guidelines for the treatment of delirium in 1999.6

DIAGNOSIS

The essential feature of delirium, according to the DSM-IV, is a disturbance of consciousness that is accompanied by cognitive deficits that cannot be accounted for by past or evolving dementia (Table 18-1).7 The ICD-10 includes disturbances in psychomotor activity, sleep, and emotion in its diagnostic guidelines (Table 18-2).8

| A disturbance of consciousness (i.e., reduced clarity of awareness of the environment) with reduced ability to focus, sustain, or shift attention A change in cognition (e.g., memory deficit, disorientation, or a language disturbance) or the development of a perceptual disturbance that is not better accounted for by a preexisting, established, or evolving dementia The disturbance develops over a short period (usually hours to days) and tends to fluctuate during the course of the day Evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is caused by the direct physiological consequences of a general medical condition |

Table 18-2 ICD-10 Diagnostic Guidelines for Delirium

| Impairment of consciousness and attention (on a continuum from clouding to coma; reduced ability to direct, focus, sustain, and shift attention) Global disturbance of cognition (perceptual distortions, illusions, and hallucinations—most often visual; impairment of abstract thinking and comprehension, with or without transient delusions, but typically with some degree of incoherence; impairment of immediate recall and of recent memory but with relatively intact remote memory; disorientation for time, as well as, in more severe cases, for place and person) Psychomotor disturbances (hypoactivity or hyperactivity and unpredictable shifts from one to the other; increased reaction time; increased or decreased flow of speech; enhanced startle reaction) Disturbance of the sleep-wake cycle (insomnia or, in severe cases, total sleep loss or reversal of the sleep-wake cycle; daytime drowsiness; nocturnal worsening of symptoms; disturbing dreams or nightmares, which may continue as hallucinations after awakening) Emotional disturbances (e.g., depression, anxiety or fear, irritability, euphoria, apathy, or wondering perplexity) |

Disturbance of the sleep-wake cycle is also common, sometimes with nocturnal worsening (“sundowning”) or even by a complete reversal of the night-day cycle, though it should be emphasized that (despite previous postulation) sleep disturbance alone does not cause delirium.9 Similarly, the term “ICU psychosis” has entered the medical lexicon; this is an unfortunate misnomer because it is predicated on the beliefs that the environment of the ICU alone is capable of inducing delirium and that the symptomatology of delirium is limited to psychosis.9

Despite wide variation in the presentation of the delirious patient, the hallmarks of delirium (although perhaps less immediately apparent) remain quite consistent from case to case. Both Chedru and Geschwind10 and Mesulam and co-workers11 regard impaired attention as the main deficit of delirium. This inattention (along with an acute onset, waxing and waning course, and overall disturbance of consciousness) forms the core of delirium, while other related symptoms (e.g., withdrawn affect, agitation, hallucinations, and paranoia) serve as a “frame” that can sometimes be so prominent as to detract from the picture itself.

Psychotic symptoms (such as visual or auditory hallucinations and delusions) are common among patients with delirium.12 Sometimes the psychiatric symptoms are so bizarre or so offensive (e.g., an enraged and paranoid patient shouts that pornographic movies are being made in the ICU) that diagnostic efforts are distracted. The hypoglycemia of a man with diabetes can be missed in the emergency department (ED) if the accompanying behavior is threatening, uncooperative, and resembling that of an intoxicated person.

While agitation may distract practitioners from making an accurate diagnosis of delirium, disruptive behavior alone will almost certainly garner some attention. The “hypoactive” presentation of delirium is more insidious, since the patient is often thought to be depressed or anxious because of his or her medical illness. Studies of quietly delirious patients show the experience to be equally as disturbing as the agitated variant13; quiet delirium is still a harbinger of serious medical pathology.14,15

The core similarities found in cases of delirium have led to postulation of a final common neurological pathway for its symptoms. Current understanding of the neurophysiological basis of delirium is one of hyperdopaminergia and hypocholinergia.16 The ascending reticular activating system (RAS) and its bilateral thalamic projections regulate alertness, with neocortical and limbic inputs to this system controlling attention. Since acetylcholine is the primary neurotransmitter of the RAS, medications with anticholinergic activity can interfere with its function, resulting in the deficits in alertness and attention that are the heralds of delirium. Similarly, it is thought that loss of cholinergic neuronal activity in the elderly (e.g., due to microvascular disease or atrophy) is the basis for their heightened risk of delirium. Release of endogenous dopamine due to oxidative stress is thought to be responsible for the perceptual disturbances and paranoia that so often lead to the delirious patient being mislabeled as “psychotic.” As we shall discuss later, both cholinergic agents (e.g., physostigmine) and dopamine blockers (e.g., haloperidol) have proven efficacious in the management of delirium.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Without a convincing temporal connection, the cause of delirium may be discovered by its likelihood in the unique clinical situation of the patient. In critical care settings, as in EDs, there are several (life-threatening) states that the clinician can consider routinely. These are states in which intervention needs to be especially prompt because failure to make the diagnosis may result in permanent central nervous system (CNS) damage. These conditions are (1) Wernicke’s disease; (2) hypoxia; (3) hypoglycemia; (4) hypertensive encephalopathy; (5) hyperthermia or hypothermia; (6) intracerebral hemorrhage; (7) meningitis/encephalitis; (8) poisoning (whether exogenous or iatrogenic); and (9) status epilepticus. These conditions are usefully recalled by the mnemonic device WHHHHIMPS (Table 18-3). Other, less urgent but still acute conditions that require interven-tion include subdural hematoma, septicemia, subacute bacterial endocarditis, hepatic or renal failure, thyrotoxicosis/myxedema, delirium tremens, anticholinergic psychosis, and complex partial seizures. If not already ruled out, when present, these conditions are easy to verify. A broad review of conditions frequently associated with delirium is provided by the mnemonic I WATCH DEATH (Table 18-4).

Table 18-3 Life-Threatening Causes of Delirium as Recalled by Use of the Mnemonic WHHHHIMPS

| Wernicke’s disease Hypoxia Hypoglycemia Hypertensive encephalopathy Hyperthermia or hypothermia Intracerebral hemorrhage Meningitis/encephalitis Poisoning (whether exogenous or iatrogenic) Status epilepticus |

Table 18-4 Conditions Frequently Associated with Delirium, Recalled by the Mnemonic I WATCH DEATH

| Infectious | Encephalitis, meningitis, syphilis, pneumonia, urinary tract infection |

| Withdrawal | Alcohol, sedative-hypnotics |

| Acute metabolic | Acidosis, alkalosis, electrolyte disturbances, hepatic or renal failure |

| Trauma | Heat stroke, burns, postoperative |

| CNS pathology | Abscesses, hemorrhage, seizures, stroke, tumors, vasculitis, normal pressure hydrocephalus |

| Hypoxia | Anemia, carbon monoxide poisoning, hypotension, pulmonary embolus, pulmonary or cardiac failure |

| Deficiencies | Vitamin B12, niacin, thiamine |

| Endocrinopathies | Hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia, hyperadrenocorticism or hypoadrenocorticism, hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism or hypoparathyroidism |

| Acute vascular | Hypertensive encephalopathy, shock |

| Toxins or drugs | Medications, pesticides, solvents |

| Heavy metals | Lead, manganese, mercury |

Bacteremia commonly clouds an individual’s mental state. In prospectively studied seriously ill hospitalized patients, delirium was commonly correlated with bacteremia.17 In that study, the mortality rate of septic patients with delirium was higher than in septic patients with a normal mental status. In the elderly, regardless of the setting, the onset of confusion should trigger concern about infection. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) and pneumonias are among the most common infections in older patients, and when bacteremia is associated with a UTI, confusion is the presenting feature nearly one-third (30%) of the time.18 Once a consultant has eliminated these basic conditions as possible causes of a patient’s disturbed brain function, there is time enough for a more systematic approach to the differential diagnosis. A comprehensive list of differential diagnoses, similar to the one compiled by Ludwig19 (slightly expanded in Table 18-5), is recommended. A quick review of this list is warranted even when the consultant is relatively sure of the diagnosis.

Table 18-5 Differential Diagnoses of Delirium

| General Cause | Specific Cause |

|---|---|

| Vascular | Hypertensive encephalopathy; cerebral arteriosclerosis; intracranial hemorrhage or thromboses; emboli from atrial fibrillation, patent foramen ovale, or endocarditic valve; circulatory collapse (shock); systemic lupus erythematosus; polyarteritis nodosa; thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura; hyperviscosity syndrome; sarcoid |

| Infectious | Encephalitis, bacterial or viral meningitis, fungal meningitis (cryptococcal, coccidioidal, Histoplasma), sepsis, general paresis, brain/epidural/subdural abscess, malaria, human immunodeficiency virus, Lyme disease, typhoid fever, parasitic (toxoplasma, trichinosis, cysticercosis, echinococcosis), Behçet’s syndrome, mumps |

| Neoplastic | Space-occupying lesions, such as gliomas, meningiomas, abscesses; paraneoplastic syndromes; carcinomatous meningitis |

| Degenerative | Senile and presenile dementias, such as Alzheimer’s or Pick’s dementia, Huntington’s chorea, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Wilson’s disease |

| Intoxication | Chronic intoxication or withdrawal effect of sedative-hypnotic drugs, such as bromides, opiates, tranquilizers, anticholinergics, dissociative anesthetics, anticonvulsants, carbon monoxide from burn inhalation |

| Congenital | Epilepsy, postictal states, complex partial status epilepticus, aneurysm |

| Traumatic | Subdural and epidural hematomas, contusion, laceration, postoperative trauma, heat stroke, fat emboli syndrome |

| Intraventricular | Normal pressure hydrocephalus |

| Vitamin deficiency | Deficiencies of thiamine (Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome), niacin (pellagra), vitamin B12 (pernicious anemia) |

| Endocrine-metabolic | Diabetic coma and shock; uremia; myxedema; hyperthyroidism, parathyroid dysfunction; hypoglycemia; hepatic or renal failure; porphyria; severe electrolyte or acid/base disturbances; paraneoplastic syndrome; Cushing’s/Addison’s syndrome; sleep apnea; carcinoid; Whipple’s disease |

| Metals | Heavy metals (lead, manganese, mercury); other toxins |

| Anoxia | Hypoxia and anoxia secondary to pulmonary or cardiac failure, anesthesia, anemia |

| Depression—other | Depressive pseudodementia, hysteria, catatonia |

Modified from Ludwig AM: Principles of clinical psychiatry, New York, 1980, Free Press.

Examination of current and past medications is essential because pharmacological agents (in therapeutic doses, in overdose, or with withdrawal) can produce psychiatric symptoms. Moreover, these considerations must be routinely reviewed, especially in patients whose drugs have been stopped because of surgery or hospitalization or whose drug orders have not been transmitted during transfer between services. Of all causes of an altered mental status, use of drugs and withdrawal from drugs are probably the most common. Some, such as lidocaine, are quite predictable in their ability to cause encephalopathy; the relationship is dose related. Other agents, such as antibiotics, usually cause delirium only in someone whose brain is already vulnerable, as in a patient with a low seizure threshold.20 Table 18-6 lists some drugs used in clinical practice that have been associated with delirium.

Table 18-6 Drugs Used in Clinical Practice That Have Been Associated with Delirium

| Antiarrhythmics |

| Disopyramide |

| Lidocaine |

| Mexiletine |

| Procainamide |

| Propafenone |

| Quinidine |

| Tocainide |

| Antibiotics |

| Aminoglycosides |

| Amodiaquine |

| Amphotericin |

| Cephalosporins |

| Chloramphenicol |

| Gentamicin |

| Isoniazid |

| Metronidazole |

| Rifampin |

| Sulfonamides |

| Tetracyclines |

| Ticarcillin |

| Vancomycin |

| Anticholinergics |

| Atropine |

| Scopolamine |

| Trihexyphenidyl |

| Benztropine |

| Diphenhydramine |

| Tricyclic antidepressants |

| Amitriptyline |

| Clomipramine |

| Desipramine |

| Imipramine |

| Nortriptyline |

| Protriptyline |

| Trimipramine |

| Thioridazine |

| Eye and nose drops |

| Anticonvulsants |

| Phenytoin |

| Antihypertensives |

| Captopril |

| Clonidine |

| Methyldopa |

| Reserpine |

| Antiviral agents |

| Acyclovir |

| Interferon |

| Ganciclovir |

| Nevirapine |

| Barbiturates |

| β-Blockers |

| Propranolol |

| Timolol |

| Cimetidine, ranitidine |

| Digitalis preparations |

| Disulfiram |

| Diuretics |

| Acetazolamide |

| Dopamine agonists (central) |

| Amantadine |

| Bromocriptine |

| Levodopa |

| Selegiline |

| Ergotamine |

| GABA agonists |

| Benzodiazepines |

| Zolpidem |

| Zaleplon |

| Baclofen |

| Immunosuppressives |

| Aminoglutethimide |

| Azacytidine |

| Chlorambucil |

| Cytosine arabinoside (high dose) |

| Dacarbazine |

| FK-506 |

| 5-Fluorouracil |

| Hexamethylmelamine |

| Ifosfamide |

| Interleukin-2 (high dose) |

| l-Asparaginase |

| Methotrexate (high dose) |

| Procarbazine |

| Tamoxifen |

| Vinblastine |

| Vincristine |

| Monoamine oxidase inhibitors |

| Tranylcypromine |

| Phenelzine |

| Procarbazine |

| Narcotic analgesics |

| Meperidine (normeperidine) |

| Pentazocine |

| Podophyllin (topical) |

| Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs |

| Ibuprofen |

| Indomethacin |

| Naproxen |

| Sulindac |

| Other medications |

| Clozaril |

| Cyclobenzaprine |

| Lithium |

| Ketamine |

| Sildenafil |

| Trazodone |

| Mefloquine |

| Sympathomimetics |

| Amphetamine |

| Aminophylline |

| Theophylline |

| Ephedrine |

| Cocaine |

| Phenylpropanolamine |

| Phenylephrine |

| Steroids, ACTH |

ACTH, Adrenocorticotropic hormone; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid.

Adapted from Cassem NH, Lake CR, Boyer WF: Psychopharmacology in the ICU. In Chernow B, editor: The pharmacologic approach to the critically ill patient, Baltimore, 1995, Williams & Wilkins; and from Drugs that may cause psychiatric symptoms, Med Lett Drugs Ther 44:59-62, 2002.

The number of drugs that can be involved either directly or indirectly (e.g., because of drug interactions) is numerous. Fortunately, certain sources provide regular reviews of published summaries and drug updates.21 Although physicians are usually aware of these hazards, a common drug, such as meperidine, when used in doses above 300 mg/day for several days, causes CNS symptoms because of the accumulation of its excitatory metabolite, normeperidine, which has a half-life of 30 hours and causes myoclonus (the best clue of normeperidine toxicity), anxiety, and ultimately seizures.22 The usual treatment is to stop the offending drug or to reduce the dose; however, at times this is not possible. Elderly patients and those with mental retardation or a history of significant head injury are more susceptible to the toxic actions of many of these drugs.

Psychiatric symptoms in medical illness can have other causes. Besides the abnormalities that may arise from the effect of the patient’s medical illness (or its treatment) on the CNS (e.g., the abnormalities produced by systemic lupus erythematosus or use of high-dose steroids), the disturbance may be the effect of the medical illness on the patient’s mind (the subjective CNS), as in the patient who thinks he is “washed up” after a myocardial infarction, quits, and withdraws into hopelessness. The disturbance may also arise from the mind, as a conversion symptom or as malingering about pain to get more narcotics. Finally, the abnormality may be the result of interactions between the sick patient and his or her environment or family (e.g., the patient who is without complaints until his family arrives, at which time he promptly looks acutely distressed and begins to whimper continuously). Nurses are commonly aware of these sorts of abnormalities, although they may go undocumented in the medical record.

EXAMINATION OF THE PATIENT

Appearance, level of consciousness, thought, speech, orientation, memory, mood, judgment, and behavior should all be assessed. In the formal mental status examination (MSE), one begins with the examination of consciousness. If the patient does not speak, a handy commonsense test is to ask oneself, “Do the eyes look back at me?” One could formally rate consciousness by using the Glasgow Coma Scale (see Chapter 81, Table 81-3), a measure that is readily understood by consultees in other specialties.23

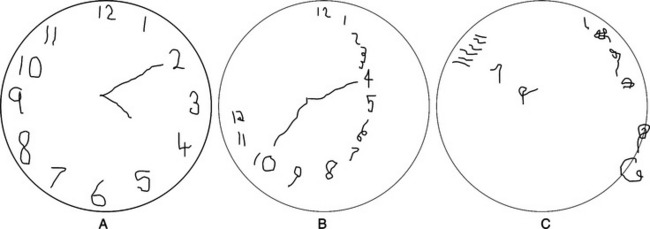

If the patient can cooperate with an examination, attention should be examined first because if this is disturbed, other parts of the examination may be invalid. One can ask the patient to repeat those letters of the alphabet that rhyme with “tree.” (If the patient is intubated, ask that a hand or finger be raised whenever the letter of the recited alphabet rhymes with tree.) Then the rest of the MSE can be performed. The Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),24 which is presented in Chapter 2, Table 2-8, is usually included. Specific defects are more important than is the total score. Other functions (such as writing, which Chedru and Geschwind10 considered to be one of the most sensitive indicators of impairment of consciousness) are often abnormal in delirium. Perhaps the most dramatic (though difficult to score objectively) test of cognition is the clock-drawing test, which can provide a broad survey of the patient’s cognitive state (Figure 18-1).25

The patient’s problem may involve serious neurological syndromes as well; however, the clinical presentation of the patient should direct the examination. In general, the less responsive and more impaired the patient is, the more one should look for “hard” signs. A directed search for an abnormality of the eyes and pupils, nuchal rigidity, hyperreflexia (withdrawal), “hung-up” reflexes (myxedema), one-sided weakness or asymmetry, gait (normal pressure hydrocephalus), Babinski’s reflexes, tetany, absent vibratory and position senses, hyperventilation (acidosis, hypoxia, or pontine disease), or other specific clues can help to verify or refute hypotheses about causality that are stimulated by the abnormalities in the examination.

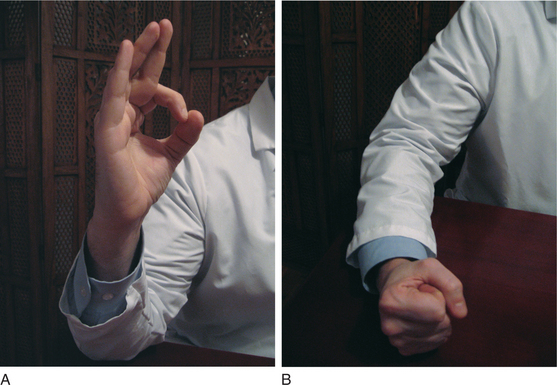

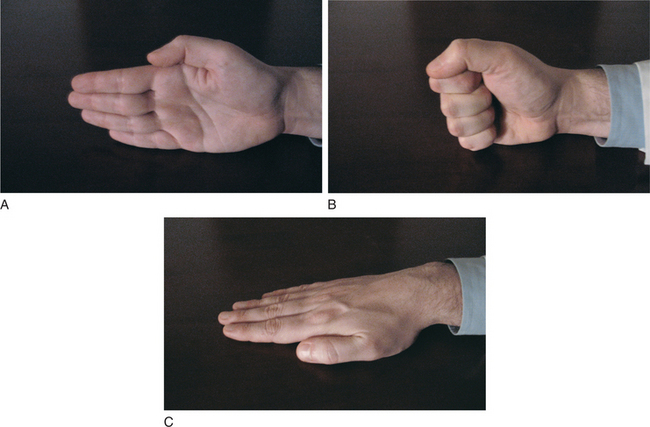

Frontal lobe function deserves specific attention. Grasp, snout, palmomental, suck, and glabellar responses are helpful when present. Hand movements thought to be related to the premotor area (Brodmann’s area 8) can identify subtle deficiencies. The patient is asked to imitate, with each hand separately, specific movements. The hand is held upright, a circle formed by thumb and first finger (“okay” sign), then the fist is closed and lowered to the surface on which the elbow rests (Figure 18-2). In the Luria sequence (Figure 18-3), one hand is brought down on a surface (a table or one’s own leg) in three successive positions: extended with all five digits parallel (“cut”), then as a fist, and then flat on the surface (“slap”). Finally, both hands are placed on a flat surface in front of the patient, one flat on the surface, the other resting as a fist. Then the positions are alternated between right and left hands, and the patient is instructed to do likewise.

Laboratory studies should be carefully reviewed, with special attention paid to indicators of infection or metabolic disturbance. Toxicological screens are also frequently helpful in allowing the inclusion or exclusion of substance intoxication or withdrawal from the differential. Neuroimaging may prove useful in the detection of intracranial processes that can result in altered mental status. Of all the diagnostic studies available, the electroencephalogram (EEG) may be the most useful tool in the diagnosis of delirium. Engel and Romano26 reported in 1959 their (now classic) findings on the EEG in delirium, namely, generalized slowing to the theta-delta range in the delirious patient, the consistency of this finding despite wide-ranging underlying conditions, and resolution of this slowing with effective treatment of the delirium. EEG findings may even clarify the etiology of a delirium, since delirium tremens is associated with low-voltage fast activity superimposed on slow waves, sedative-hypnotic toxicity produces fast beta activity (>12 Hz), and hepatic encephalopathy is classically associated with triphasic waves.27

SPECIFIC MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES FOR DELIRIUM

Thoughts about (and treatment of) delirium have changed dramatically in the past three decades. Thirty years ago, atropine was routinely administered to newly admitted coronary care unit (CCU) patients with bradycardia. Some patients, particularly older ones with preexisting organic brain disease, developed delirium. For such patients, parenteral propantheline bromide (Pro-Banthine), a quaternary ammonium compound that does not cross the blood-brain barrier and is equally effective in treating bradycardia, was substituted. This approach may still be taken, but problems are seldom so simple. Often the drugs that cause delirium (such as lidocaine or prednisone) cannot be changed without causing harm to the patient. Alternatively, pain may cause agitation in a delirious patient. Morphine sulfate can relieve pain but may unfortunately lead to decreases in blood pressure and respiratory rate.

Psychosocial or environmental measures are rarely effective in the treatment of a bona fide delirium of uncertain or unknown cause. Nevertheless, it is commendable to have hospital rooms with windows, calendars, clocks, and a few mementos from home on the walls28; soft and low lighting at night helps “sundowners”; and, most of all, a loving family in attendance reassures and reorients the patient. The psychiatric consultant is often summoned because psychosocial measures have failed to prevent or to treat the patient’s delirium. Restraints (e.g., Poseys, geriatric chairs, “vests,” helmets, and locked leather restraints for application to one or more extremities, chest, and [even] head) are also available and quite useful to protect patients from inflicting harm on themselves or staff. One or several of these is often in place when the consultant arrives. One hoped-for outcome of the consultation is that the use of these devices can be reduced or eliminated. The unfortunate misnomer chemical restraint is frequently applied to the most helpful class of drugs for delirium (i.e., neuroleptics). However, physicians do not use chemical restraints (i.e., tear gas, pepper spray, mace, or nerve gas) in the treatment of agitated patients.

Anticholinergic delirium can be reversed by intravenous (IV) physostigmine (in doses starting at 0.5 to 2 mg). Caution is essential with use of this agent as the autonomic nervous system of the medically ill is generally less stable than it is in a healthy patient who has developed an anticholinergic delirium as a result of a voluntary or accidental overdose. Moreover, if there is a reasonably high amount of an anticholinergic drug on board that is clearing from the system slowly, the therapeutic effect of physostigmine, although sometimes quite dramatic, is usually short-lived. The cholinergic reaction to intravenously administered physostigmine can cause profound bradycardia and hypotension, thereby multiplying the complications.29,30 It should also be noted that a continuous IV infusion of physostigmine has been successfully used to manage a case of anticholinergic poisoning.31 Because of the diagnostic value of physostigmine, one may wish to use it even though its effects will be short-lived. If one uses an IV injection of 1 mg of physostigmine, protection against excessive cholinergic reaction can be provided by preceding this injection with an IV injection of 0.2 mg of glycopyrrolate. This anticholinergic agent does not cross the blood-brain barrier and should protect the patient from the peripheral cholinergic actions of physostigmine.

DRUG TREATMENT

Neuroleptics are the agent of choice for delirium. Haloperidol is probably the antipsychotic most commonly used to treat agitated delirium in the critical care setting; its effects on blood pressure, pulmonary artery pressure, heart rate, and respiration are milder than those of the benzodiazepines, making it an excellent agent for delirious patients with impaired cardiorespiratory status.32

Although haloperidol can be administered orally or parenterally, acute delirium with extreme agitation typically requires use of parenteral medication. IV administration is preferable to intramuscular (IM) administration because drug absorption may be poor in distal muscles if delirium is associated with circulatory compromise or with borderline shock. The deltoid is probably a better IM injection site than the gluteus muscle, but neither is as reliable as is the IV route. Second, as the agitated patient is commonly paranoid, repeated painful IM injections may increase the patient’s sense of being attacked by enemy forces. Third, IM injections can complicate interpretations of muscle enzyme studies if enzyme fractionation is not readily available. Fourth, and most important, haloperidol is less likely to produce extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) when given IV than when given IM or by mouth (PO), at least for patients without a prior serious psychiatric disorder.33

In contrast to the immediately observable sedation produced by IV benzodiazepines, IV haloperidol has a mean distribution time of 11 minutes in normal volunteers34; this may be even longer in critically ill patients. The mean half-life of IV haloperidol’s subsequent, slower phase is 14 hours. This is still a more rapid metabolic rate than the overall mean half-lives of 21 and 24 hours for IM and PO doses. The PO dose has about half the potency of the parenteral dose, so 10 mg of PO haloperidol corresponds to 5 mg given IV or IM.

Haloperidol has not been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for IV administration. However, any approved drug can be used for a nonapproved indication or route if justified as “innovative therapy.” For critical care units desirous of using IV haloperidol, one approach is to present this to the hospital’s institutional review board (IRB) or human studies committee with a request to use the drug with careful monitoring of results based on the fact that it is the drug of choice for the patient’s welfare, it is the safest drug available for this purpose, and it is justifiable as innovative therapy. After a period of monitoring, the committee can choose to make the use of the drug routine in that particular hospital.

In Europe, IV haloperidol has been used to treat delirium tremens and acute psychosis and to premedicate patients scheduled for electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Its use has been associated with few adverse effects on blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, or urinary output and has been linked with few EPS. The reason for the latter is not known. Studies of the use of IV haloperidol in psychiatric patients have not shown that these side effects were fewer. The reason for their rare appearance after IV administration in medically ill patients may be due to the fact that many of the medically ill patients have other medications in their system, especially benzodiazepines (that are protective against EPS) or that patients with psychiatric disorders are more susceptible to EPS.33

Haloperidol can be combined every 30 minutes with simultaneous parenteral lorazepam doses (starting with 1 to 2 mg). Because the effects of lorazepam are noticeable within 5 to 10 minutes, each dose can precede the haloperidol dose, observed for its impact on agitation, and increased if it is more effective. Some believe that the combination leads to a lower overall dose of each drug.35

After calm is achieved, agitation should be the sign for a repeat dose. Ideally, the total dose of haloperidol on the second day should be a fraction of that used on day 1. After complete lucidity has been achieved, the patient needs to be protected from delirium only at night, by small doses of haloperidol (1 to 3 mg), which can be given PO. As in the treatment of delirium tremens, the consultant is advised to stop the agitation quickly and completely at the outset rather than barely keep up with it over several days. The maximum total dose of IV haloperidol to be used as an upper limit has not been established, although IV administration of single bolus doses of 200 mg have been used, and up to 1,600 mg has been used in a 24-hour period.36 The highest requirements have been seen with delirious patients on the intraaortic balloon pump.37 A continuous infusion of haloperidol has also been used to treat severe, refractory delirium.38

Several centers have discovered that use of IV haloperidol is associated with the development of torsades de pointes (TDP).39–43 The reasons for this are unclear, although particular caution is urged when levels of potassium and magnesium are low, when a prolonged QT interval is noted, when hepatic compromise is present, or when a specific cardiac abnormality (e.g., mitral valve prolapse or a dilated ventricle) exists. Progressive QT widening after haloperidol administration should alert one to the danger, however infrequent it may be in practice (4 of 1,100 cases in one unit).40 Delirious patients who are candidates for IV haloperidol require care-ful screening. Serum potassium and magnesium should be within normal range and a baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) checked for the pretreatment QT interval corrected for heart rate (QTc) interval. QT interval prolongation occurs in some patients with alcoholic liver disease; this finding is associated with adverse outcomes (e.g., sudden cardiac death).44

In the past, IV droperidol was recommended as an alternative agent to haloperidol in part because it was approved for IV administration by the FDA. Unfortunately, its label was revised to include a black box warning for QT prolongation leading to TDP and death.45 This has limited the frequency of its use.

The availability of injectable formulations of both olanzapine and ziprasidone has prompted a growing interest in the use of the second-generation antipsychotics in the management of delirium.46 Risperidone has the most available data supporting its use, with multiple studies showing it to be efficacious and safe for the treatment of delirium,47–49 and one small randomized double-blind comparative study finding no significant difference in efficacy when compared with haloperidol.50 The other members of this class (olanzapine, ziprasidone, quetiapine, clozapine, and aripiprazole) have far less supporting data, though some small studies seem to indicate some promise for management of delirium.51–55 Agranulocytosis associated with clozapine and the resultant regulation of its use effectively eliminates any routine application of it in the management of delirium. All drugs in this class feature an FDA black box warning indicating an increased risk of death when used to treat behavioral problems in elderly patients with dementia. Similar warnings regarding a potential increased risk of cerebrovascular events are reported for risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole. With decades of clinical experience in the use of haloperidol, and a dearth of available data on these newer agents, haloperidol remains the agent of choice for the treatment of delirium.

To date, there are few data to support pharmacological prophylaxis of delirium for the critically ill, although one recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study examining the preoperative use of haloperidol in elderly patients undergoing hip surgery indicated decreases in the severity and duration of delirium, as well as the length of hospital stay, but no statistically significant decrease in the actual incidence of delirium.56 There are also some limited data suggesting that the procholinergic action of cholinesterase inhibitors provides some protection against the development of delirium.57,58

DELIRIUM IN SPECIFIC DISEASES

Critically ill patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection may be more susceptible to the EPS of haloperidol, and to neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS),59–61 leading an experienced group to recommend use of molindone.62 The latter is associated with fewer of such effects; while it is available only as an oral agent, it can be prescribed from 5 to 25 mg at appropriate intervals or, in a more acute situation, 25 mg every hour until calm is achieved. Risperidone (0.5 to 1 mg per dose) is another recommended PO agent. If parenteral medication is required, 10 mg of chlorpromazine has been effective. Perphenazine is readily available for parenteral use as well, and 2 mg doses can be used effectively.

Patients with Parkinson’s disease pose a special problem because dopamine blockade aggravates their condition. If PO treatment of delirium or psychosis is possible, clozapine, starting with a small dose of 6.25 or 12.5 mg, is probably the most effective agent available that does not exacerbate the disease. With the risk of agranulocytosis attendant to the use of clozapine, quetiapine may play a valuable role in this population, since its very low affinity for dopamine receptors is less likely to exacerbate this disorder.63

IV benzodiazepines (particularly diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, and lorazepam) are routinely used to treat agitated states, particularly delirium tremens, and alcohol withdrawal.64 Neuroleptics have also been used successfully, and both have been combined with clonidine. IV alcohol is also extremely effective in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal states, particularly if the patient does not seem to respond as rapidly as expected to higher doses of benzodiazepines. The inherent disadvantage is that alcohol is toxic to both liver and brain, although its use can be quite safe if these organs do not show already extensive damage (and sometimes quite safe even when they do). Nonetheless, use of IV alcohol should be reserved for extreme cases of alcohol withdrawal when other, less toxic measures have failed. A 5% solution of alcohol mixed with 5% dextrose in water run at 1 ml per minute often achieves calm quickly.

Propofol, a relatively new agent for the sedation of critically ill patients, can also be extremely effective in managing agitation.65–67 It has both moderate respiratory depressant and vasodilator effects, although hypotension can be minimized by avoidance of boluses of the drug. Impaired hepatic function does not slow metabolic clearance, but clearance does decline with age and its half-life is significantly longer in the elderly. When compared with midazolam as a sedative for postoperative coronary artery bypass graft patients, both drugs, without affecting cardiac output, provided safe and effective sedation and lowered arterial blood pressure and heart rates. The group treated with propofol, however, had significantly lower heart rates during the first 2 hours and significantly lower blood pressures 5 to 10 minutes after the initial dose (mean loading doses for propofol and midazolam were 0.24 mg/kg and 0.012 mg/kg, and maintenance doses 0.76 mg/kg/hr and 0.018 mg/kg/hr). In the propofol group, there was a reduced need for sodium nitroprusside and supplemental opioids were less often required.68

In a prospective, randomized, crossover, placebo-controlled trial, propofol’s effect on critically ill patients’ response to chest physiotherapy was studied. Propofol, in an IV bolus dose of 0.75 mg/kg, significantly reduced the hemodynamic and metabolic stresses caused by chest physiotherapy.69 This drug’s rapid onset and short duration make it especially useful for treatment of short periods of stress. When rapid return to alertness from sedation for an uncompromised neurological examination is indicated, propofol is a nearly ideal agent70; however, its use in the treatment of a prolonged delirious state has specific disadvantages.71 Delivered as a fat emulsion containing 0.1 g of fat per milliliter, propofol requires a dedicated IV line, and drug accumulation can lead to a fat-overload syndrome that has been associated with overfeeding and with significant CO2 production, hypertriglyceridemia, ketoacidosis, seizure activity 6 days after discontinuation, and even fatal respiratory failure.71–73 Obese patients provide a high volume of distribution, and their doses should be calculated using estimated lean, rather than actual, body mass. If the patient is receiving fat by parenteral feeding, this must be accounted for or eliminated and adequate glucose infusion provided to prevent ketoacidosis. Although no clear association has been demonstrated with addiction, tolerance, or withdrawal, doses seem to require escalation after 4 to 7 days’ infusion. Seizures seen after withdrawal and muscular rigidity during administration are poorly understood. The drug is costly when prolonged infusions are used because propofol costs about three to four times as much as equivalent quantities of midazolam.

Dexmedetomidine is a selective α2-adrenergic agonist used for sedation and analgesia in the ICU setting. Its relative lack of amnestic effect may limit its use in the treatment of the delirious patient due to an increased likelihood of distressing recollections persisting from the period of sedation.74

Drug infusions may be more effective and efficient than intermittent bolus dosing because the latter may intensify side effects (such as hypotension), waste time of critical care personnel, and permit more individual error. The contents of the infusion can address simultaneously multiple aspects of a patient’s difficulties in uniquely appropriate ways. The report of the sufentanil, midazolam, and atracurium admixture for a patient who required a temporary biventricular assist device is an excellent example of multiple-drug infusion and creative problem-solving.75,76

CONCLUSIONS

Of all psychiatric diagnoses, delirium demands the most immediate attention since delay in identification and treatment might allow the progression of serious and irreversible pathophysiological changes. Unfortunately, delirium is all too often underemphasized, misdiagnosed, or altogether missed in the general hospital setting.77–79 Indeed, it was not until their most recent editions that major medical and surgical texts corrected chapters indicating that delirium was the result of anxiety or depression, rather than an underlying somatic cause that required prompt investigation. In the face of this tradition of misinformation, it often falls to the psychiatric consultant to identify and manage delirium, while alerting and educating others to its significance.

1 Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004;291:1753-1762.

2 Thomason JW, Shintani A, Peterson JF, et al. Intensive care unit delirium is an independent predictor of longer hospital stay: a prospective analysis of 261 non-ventilated patients. Crit Care. 2005;9:R375-R381.

3 Milbrandt EB, Deppen S, Harrison PL, et al. Costs associated with delirium in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:955-962.

4 Franco K, Litaker D, Locala J, et al. The cost of delirium in the surgical patient. Psychosomatics. 2001;42:68-73.

5 McNicoll L, Pisani MA, Zhang Y, et al. Delirium in the intensive care unit: occurrence and clinical course in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:591-598.

6 American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with delirium. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(5 suppl):1-20.

7 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, ed 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

8 World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1992.

9 McGuire BE, Basten CJ, Ryan CJ, et al. Intensive care unit syndrome: a dangerous misnomer. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:906-909.

10 Chedru F, Geschwind N. Writing disturbances in acute confusional states. Neuropsychologia. 1972;10:343-353.

11 Mesulam MM, Waxman SG, Geschwind N, et al. Acute confusional state with right middle cerebral artery infarctions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1976;39:84-89.

12 Webster R, Holroyd S. Prevalence of psychotic symptoms in delirium. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:519-522.

13 Breitbart W, Gibson C, Tremblay A. The delirium experience: delirium recall and delirium-related distress in hospitalized patients with cancer, their spouses/caregivers, and their nurses. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:183-194.

14 Liptzin B, Levkoff SE. An empirical study of delirium subtypes. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;161:843-845.

15 Olofsson SM, Weitzner MA, Valentine AD, et al. A retrospective study of the psychiatric management and outcome of delirium in the cancer patient. Support Care Cancer. 1996;4:351-357.

16 Brown TM. Basic mechanisms in the pathogenesis of delirium. In Stoudemire A, Fogel BS, Greenberg DB, editors: Psychiatric care of the medical patient, ed 2, New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

17 Eidelman LA, Putterman D, Sprung CL. The spectrum of septic encephalopathy. JAMA. 1996;275:470-473.

18 Barkham TM, Martin EC, Eykyn SJ. Delay in the diagnosis of bacteraemic urinary tract infection in elderly patients. Age Aging. 1996;25:130-132.

19 Ludwig AM. Principles of clinical psychiatry. New York: Free Press, 1980.

20 Snavely SR, Hodges GR. The neurotoxicity of antibacterial agents. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:92-104.

21 Drugs that may cause psychiatric symptoms. Med Letter Drugs Ther. 2002;44:59-62.

22 Shochet RB, Murray GB. Neuropsychiatric toxicity of meperidine. J Intens Care Med. 1988;3:246-252.

23 Bastos PG, Sun X, Wagner DP, et al. Glasgow Coma Scale score in the evaluation of outcome in the intensive care unit: findings from the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation III study. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:1459-1465.

24 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State,” a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189-198.

25 Freedman M, Leach L, Kaplan E, et al. Clock drawing: a neuropsychological analysis. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

26 Engel GL, Romano J. Delirium, a syndrome of cerebral insufficiency. J Chronic Dis. 1959;9:260-277.

27 Jacobson S, Jerrier H. EEG in delirium. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2000;5:86-92.

28 Dubois MJ, Bergeron N, Dumont M, et al. Delirium in an intensive care unit: a study of risk factors. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:1297-1304.

29 Pentel P, Peterson CD. Asystole complicating physostigmine treatment of tricyclic antidepressant overdose. Ann Emerg Med. 1980;9:588-590.

30 Boon J, Prideaux PR. Cardiac arrest following physostigmine. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1980;8:92-93.

31 Stern TA. Continuous infusion of physostigmine in anticholinergic delirium: case report. J Clin Psychiatry. 1983;44:463-464.

32 Sos J, Cassem NH. The intravenous use of haloperidol for acute delirium in intensive care settings. In: Speidel H, Rodewald G, editors. Psychic and neurological dysfunctions after open heart surgery. Stuttgart: George Thieme Verlag, 1980.

33 Menza MA, Murray GB, Holmes VF, et al. Decreased extrapyramidal symptoms with intravenous haloperidol. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48:278-280.

34 Forsman A, Ohman R. Pharmacokinetic studies on haloperidol in man. Curr Therap Res. 1976;10:319.

35 Adams F, Fernandez F, Andersson BS. Emergency pharmacotherapy of delirium in the critically ill cancer patient: intravenous combination drug approach. Psychosomatics. 1986;27(suppl 1):33-37.

36 Tesar GE, Murray GB, Cassem NH. Use of high-dose intravenous haloperidol in the treatment of agitated cardiac patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1985;5:344-347.

37 Sanders KM, Stern TA, O’Gara PT, et al. Delirium after intra-aortic balloon pump therapy. Psychosomatics. 1992;33:35-41.

38 Fernandez F, Holmes VF, Adams F, et al. Treatment of severe, refractory agitation with a haloperidol drip. J Clin Psychiatry. 1988;49:239-241.

39 Metzger E, Friedman R. Prolongation of the corrected QT and torsades de pointes cardiac arrhythmia associated with intravenous haloperidol in the medically ill. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1993;13:128-132.

40 Wilt JL, Minnema AM, Johnson RF, et al. Torsades de pointes associated with the use of intravenous haloperidol. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:391-394.

41 Hunt N, Stern TA. The association between intravenous haloperidol and torsades de pointes: three cases and a literature review. Psychosomatics. 1995;36:541-549.

42 Di Salvo TG, O’Gara PT. Torsades de pointes caused by high-dose intravenous haloperidol in cardiac patients. Clin Cardiol. 1995;18:285-290.

43 Zeifman CWE, Friedman B. Torsades de pointes: potential consequence of intravenous haloperidol in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care World. 1994;11:109-112.

44 Day CP, James OFW, Butler TJ, et al. QT prolongation and sudden cardiac death in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Lancet. 1993;341:1423-1428.

45 Kao LW, Kirk MA, Evers SJ, et al. Droperidol, QT prolongation and sudden death: what is the evidence? Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:546-558.

46 Schwartz TL, Masand PS. The role of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of delirium. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:171-174.

47 Horikawa N, Yamazaki T, Miyamoto K, et al. Treatment for delirium with risperidone: results of a prospective open trial with 10 patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25:289-292.

48 Parellada E, Baeza I, de Pablo J, et al. Risperidone in the treat-ment of patients with delirium. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:348-353.

49 Mittal D, Jimerson NA, Neely EP, et al. Risperidone in the treatment of delirium: results from a prospective open-label trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:662-667.

50 Han CS, Kim YK. A double-blind trial of risperidone and haloperidol for the treatment of delirium. Psychosomatics. 2004;45:297-301.

51 Sipahimalani A, Masand PS. Olanzapine in the treatment of delirium. Psychosomatics. 1998;39:422-430.

52 Schwartz TL, Masand PS. Treatment of delirium with quetiapine. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;2:10-12.

53 Leso L, Schwartz TL. Ziprasidone treatment of delirium. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:61-62.

54 Breitbart W, Tremblay A, Gibson C. An open trial of olanzapine for the treatment of delirium in hospitalized cancer patients. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:175-182.

55 Skrobik YK, Bergeron N, Dumont M, et al. Olanzapine vs haloperidol: treatment of delirium in the critical care setting. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:444-449.

56 Kalisvaart KJ, de Jonghe JF, Bogaards MJ, et al. Haloperidol prophylaxis for elderly hip-surgery patients at risk for delirium: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1658-1666.

57 Dautzenberg PL, Wouters CJ, Oudejans I, et al. Rivastigmine in prevention of delirium in a 65 year old man with Parkinson’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18(6):555-556.

58 Dautzenberg PL, Mulder LJ, Olde Rikkert MG, et al. Delirium in elderly hospitalized patients: protective effects of chronic rivastigmine usage. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(7):641-644.

59 Fernandez F, Levy JK, Mansell PWA. Management of delirium in terminally ill AIDS patients. Int J Psychiatr Med. 1989;19:165-172.

60 Breitbart W, Marotta RF, Call P. AIDS and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Lancet. 1988;2:1488-1489.

61 Caroff SN, Rosenberg H, Mann SC, et al. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome in the critical care unit. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:2609.

62 Fernandez F, Levy JK. The use of molindone in the treatment of psychotic and delirious patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: case reports. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1993;15:31-35.

63 Lauterbach EC. The neuropsychiatry of Parkinson’s disease and related disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2004;27:801-825.

64 Olmedo R, Hoffman RS. Withdrawal syndromes. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2000;18:237-288.

65 Barr J, Donner A. Optimal intravenous dosing strategies for sedatives and analgesics in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin. 1995;11:827-847.

66 Cohen IL, Gallagher TJ, Pohlman AS, et al. Management of the agitated intensive care unit patient. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(1 suppl):S97-S123.

67 Hurford WE. Sedation and paralysis during mechanical ventilation. Respir Care. 2002;47:334-347.

68 Higgins TL, Yared JP, Estafanous FG, et al. Propofol versus midazolam for intensive care unit sedation after coronary artery bypass grafting. Crit Care Med. 1994;22:1415-1423.

69 Cohen D, Horiuchi K, Kemper M, et al. Modulating effects of propofol on metabolic and cardiopulmonary responses to stressful intensive care unit procedures. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:612-617.

70 Mirski MA, Muffelman B, Ulatowski JA, et al. Sedation for the critically ill neurologic patient. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:2038-2053.

71 Valenti JF, Anderson GL, Branson RD, et al. Disadvantages of prolonged propofol sedation in the critical care unit. Crit Care Med. 1994;22:710-712.

72 Mirenda J. Prolonged propofol sedation in the critical care unit. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1304-1305.

73 El-Ebiary M, Torres A, Ramirez J, et al. Lipid deposition during the long-term infusion of propofol. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1928-1930.

74 Gertler R, Brown HC, Mitchell DH, et al. Dexmedetomidine: a novel sedative-analgesic agent. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2001;14:13-21.

75 Turnage WS, Mangar D. Sufentanil, midazolam, and atracurium admixture for sedation during mechanical circulatory assistance. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:1099-1100.

76 Riker RR, Fraser GL, Cox PM. Continuous infusion of haloperidol controls agitation in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 1994;22:433-440.

77 Farrell KR, Ganzini L. Misdiagnosing delirium as depression in medically ill elderly patients. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:2459-2464.

78 Boland RJ, Diaz S, Lamdan RM, et al. Overdiagnosis of depres-sion in the general hospital. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996;18:28-35.

79 Ely EW, Siegel MD, Inouye SK. Delirium in the intensive care unit: an under-recognized syndrome of organ dysfunction. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;22:115-126.