Dental Emergencies

Edited by Peter Cameron

17.1 Dental emergencies

Sashi Kumar

Anatomy

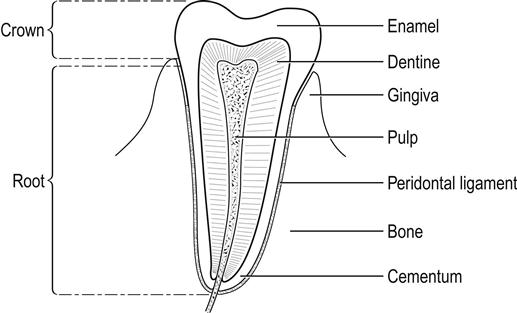

The tooth consists of the crown, which is exposed, and the root, which lies within the socket covered by the gum and serves to anchor the tooth. The gingival pulp carries the neurovascular structures via the root canal and is covered by dentine which, in turn, is covered by enamel, the hardest substance in the body (Fig. 17.1.1).

The deciduous teeth are 20 in number and erupt between the ages of 6 months and 2 years. The permanent dentition begins to erupt at around age 6 and, in the adult, consists of 32 teeth.

Dental caries

The most common cause of toothache or odontalgia is caries. Dental caries-related emergencies account for up to 52% of first contact with a dentist for children below the age of 3 years [1]. Dental caries is the cause of emergency visits to a dentist in 73% of paediatric patients [2]. Pain associated with dental caries is of a dull, throbbing nature, localized to a specific area and aggravated by changes in temperature in the oral cavity (hypersensitivity to hot and cold food or fluids).

Examination reveals tenderness of the offending tooth when tapped with a tongue depressor or a mirror. Management includes symptomatic pain relief using analgesics, such as paracetamol with or without codeine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and urgent referral to the dentist.

Periodontal emergencies

Pain is the most common cause of self-referral to the emergency department for dental problems. The common conditions causing dental pain are acute apical periodontitis and reversible and irreversible pulpitis resulting from dental caries [3]. Symptoms include painful swollen gums with or without halitosis. On occasions, frank pus or bleeding from the gums may be the presenting symptom. At all stages, varying degrees of pain associated with inflammation are invariably present [4].

Infected gums could be an early clinical sign of undiagnosed diabetes, HIV, graft-versus-host disease in radiation therapy for head and neck malignancy and bone marrow transplantation.

Management includes diagnosis of the periodontal disease and the offending tooth. Symptomatic pain relief can be achieved with analgesics, NSAIDs and warm saline rinses. Routine antibiotic therapy is not required unless there is evidence of gross infection locally, regional lymphadenopathy or fever. In all cases, urgent review by the dentist is mandatory.

Acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG) is a severe form of gingivitis which could be related to stress and needs antibiotic cover and urgent referral to the dentist.

Alveolar osteitis (dry socket)

Dry socket occurs between 2 and 5 days following dental extraction. The dull throbbing pain is due to the collection of necrotic clot and debris in the socket. The condition is diagnosed on the history and examination, which confirms the acutely tender extraction site.

Treatment consists of irrigation of the extraction site to remove the necrotic material and packing the socket with sterile gauze soaked in local anaesthetic, such as cophenylcaine, followed by urgent dental review [5].

Postdental extraction bleeding

Bleeding from the socket post-extraction within 48 h is due to reactionary haemorrhage due to opening up of the small divided blood vessels. Bleeding after 5 days is secondary haemorrhage due to infection that destroys the organizing blood clot.

General causes, such as hypertension and warfarin therapy, need to be addressed to control the bleeding.

Management is essentially reassurance, careful suction to clear the debris and clot in the socket, followed by packing with gauze soaked in lignocaine with adrenaline or cophenylcaine and pressure.

Dilute aminocaproic acid (IV Amicar) 5 mL in 10 mL of normal saline to rinse the mouth. Use Amicar or tranexamic acid-soaked gauze to bite on, applying direct pressure for about 30 min and repeat as required to control the bleeding. Occasionally, the gingival flaps may need to be sutured under local anaesthetic.

Traumatic dental emergencies

Tooth avulsion is probably the most serious tooth injury. An avulsed tooth, if reimplanted in the socket within 30 min, has a 90% survival rate [6]. The mechanism of injury in such cases is usually either accidental sports-related facial injuries or assault.

Management

If the patient makes telephone contact with the emergency department, the patient is advised to locate the tooth because, even if the crown is broken, the root may be intact. The tooth should not be handled by the root to avoid damage to the periodontal ligament fibres; it is washed in running cold water and replaced in the socket. If this is not possible, place the tooth in the cheek or under the tongue and proceed immediately to the dentist. Do not scrub the tooth [7,8].

The best transportation medium for an avulsed tooth is saliva. Cold milk or iced salt water are suitable alternatives.

If the patient arrives in the emergency department with the tooth, clean it by holding it by the crown in cold running water; any foreign debris should be removed with forceps. The tooth should not be allowed to dry. Following irrigation, the tooth should be placed in the socket as near the original position as possible and the patient referred to a dentist for stabilization with an archbar or orthodontic bands.

If the reimplanted tooth remains mobile after 2 weeks, it should be extracted. The complications of reimplantation are ankylosis and loss of viability.

The 2010 Dental Trauma Guide by the Danish Dental Association supported by the International Association of Dental Traumatology provides an interactive drop down menu on how to deal with every possible dental trauma [9].

Dentoalveolar trauma in children

Concussion and subluxation

Concussion is an injury to the tooth without displacement or mobility. Subluxation is when the tooth is mobile but not displaced.

Management

Periapical X-rays as baseline, soft diet for a week and local dentist follow up.

Intrusive luxation

Most common injury to upper primary incisors after a fall.

Management

If the crown is visible leave the tooth to re-erupt. If the whole tooth is intruded, extraction is required as it might affect the permanent dentition underneath.

Extrusive and lateral subluxation

If there is excessive mobility or displacement, extraction is recommended.

Avulsion

Avulsed primary teeth should not be replanted. Unless there is extensive soft-tissue damage, antibiotics are not required.

Dental fractures

The incidence of fractured teeth is reported to be 5 and 4.4 per 100 adults per year for all teeth and posterior teeth, respectively [10]. Based on the above statistics, it can be deduced that the likelihood of experiencing a fractured frontal/anterior tooth is about 1 in 20 in a given year in adults and 1 in 23 for posterior teeth.

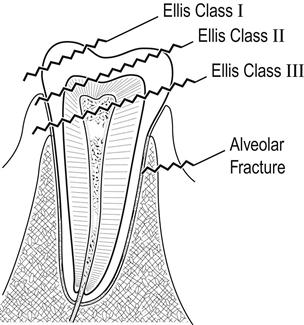

Traumatic injuries to the teeth have been classified as follows [11]:

Class I: simple fracture of the enamel of the crown.

Class II: extensive fracture of the crown involving dentine.

Class III: extensive fracture of the crown involving dentine and dental pulp.

Class IV: extensive involvement and exposure of the entire pulp.

Class V: totally avulsed or luxated teeth.

Class VI: fracture of the root with or without loss of crown structure.

Class VII: displacement of tooth without fracture of crown or root.

Class VIII: fracture of the crown in its entirety (Fig. 17.1.2).

Management

Emergency management includes reassurance, adequate analgesia, replacement of an avulsed tooth in the socket and immediate referral to a dentist for further evaluation and appropriate management.

Specific treatment depends on the type of fracture [12]:

Class I: treated by smoothing the enamel margins and applying topical fluoride to the fracture site.

Class I: treated by smoothing the enamel margins and applying topical fluoride to the fracture site.

Class IV: conventional filling for permanent teeth and total pulpectomy for a primary tooth.

Class IV: conventional filling for permanent teeth and total pulpectomy for a primary tooth.

Class V: managed as for an avulsed tooth.

Class V: managed as for an avulsed tooth.

Class VI: if the pulp is necrotic, pulpectomy and root canal therapy.

Class VI: if the pulp is necrotic, pulpectomy and root canal therapy.

When a tooth is missing following facial trauma, a thorough intraoral examination is followed by appropriate radiographs to avoid missing an intruded tooth. When full intrusion of a tooth is suspected, a facial computed tomography (CT) scan may aid definite diagnosis [13].

When a tooth is missing following facial trauma, a thorough intraoral examination is followed by appropriate radiographs to avoid missing an intruded tooth. When full intrusion of a tooth is suspected, a facial computed tomography (CT) scan may aid definite diagnosis [13].

Temporomandibular dislocation

Temporomandibular dislocation can result from congenital weakness of ligaments, iatrogenic causes (traumatic extractions, prolonged dental procedures and direct laryngoscopy), trauma, drugs, epilepsy and even simple yawning. The dislocation may be unilateral but is more commonly bilateral. The condyle is most frequently dislocated anterior to the articular eminence.

The patient presents with an open bite and malocclusion. If unilateral, the mandible deviates to the unaffected side. The patient complains of severe pain in the ear and is unable to open or close the mouth fully. Management includes diagnosis and reduction. The patient is seated, with posterior head support, and the muscle spasm is overcome by using intravenous benzodiazepines, such as midazolam, and narcotic analgesia, such as fentanyl.

The mandible is held by the clinician by both hands, with the gloved thumbs intraorally just lateral to the lower molars. The mandibular condyle is then manipulated in a downward and backward direction below the articular eminence. In bilateral dislocation, it may be easier to reduce one side at a time using a lateral rocking motion.

Following the procedure, a post-reduction radiograph is taken to confirm enlocation. The patient is discharged with a supportive bandage to the mandible and a soft diet advised for the next few days. Follow up by the maxillofacial surgeon is essential, as temporomandibular dysfunction due to damage to the fibrous cartilage can lead to ongoing symptoms or recurrent dislocations.

Dental infection and abscess (odontogenic infection)

Dentofacial infections usually arise from necrotic pulps, periodontal pockets or pericoronitis.

The symptoms are pain and swelling of the adjacent gingival tissue with facial swelling and fever.

Examination reveals erythema and tender swelling of the gingiva and, in severe cases, frank pus with halitosis. The offending tooth is tender on percussion.

Gingival probing, X-rays and orthopontomogram (OPG) confirm the diagnosis.

Management

Periapical abscess requires root canal (endodontic) treatment and extraction in severe cases.

Periodontal abscess requires scaling and root planing (periodontal) treatment and extraction in severe cases.

Complications include spread of infection into the submental, submandibular, parapharyngeal spaces of the neck and Ludwig’s angina (cellulitis of the floor of the mouth), which requires intravenous antibiotic therapy and drainage if a collection is diagnosed on the CT scan.

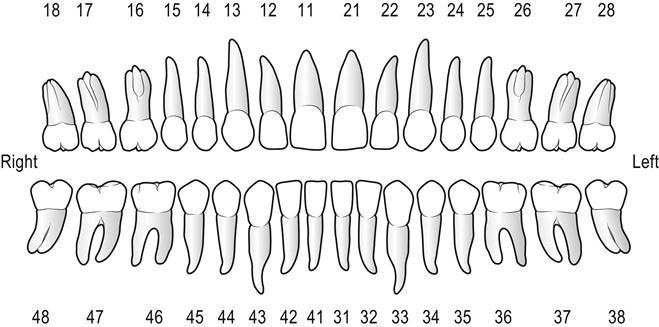

Dental nomenclature

The international numbering system of teeth should be strictly adhered to in any form of communication. The mouth is divided into four quadrants. The right maxillary as 1, left maxillary as 2, left mandibular as 3 and the right mandibular as 4 (Fig. 17.1.3).

There are five primary teeth and eight permanent teeth in each quadrant.