Section 16 Eyes

16.1 Ocular emergencies

Painless loss of vision

Management of specific injuries

Penetrating injury

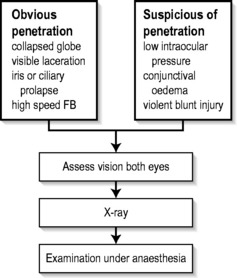

Examination of the eye involves the instillation of sterile topical anaesthetic drops, followed by a gentle eye toilet removing debris, clot and glass from the face and lids. The lids should be opened without pressure (Fig. 16.1.1). The penetration may be evidenced by an obvious laceration or presence of prolapsed tissue with collapse of the globe. Conjunctival oedema (chemosis) and low intraocular pressure (IOP) may indicate an occult perforation or bursting injury.

When a penetrating injury is either suspected or established, the patient must be transferred without delay to a centre where appropriate surgical facilities are available. During transport, the eye should be covered with a sterile pad and a plastic cone. Vomiting should be prevented with antiemetics, and the fasted patient given intravenous fluids as necessary.

Prevention

Australian seatbelt legislation has markedly reduced the incidence of penetrating eye injuries in road trauma, but eye problems still occur from violent head and facial trauma in addition to the neurological complications of head injury.1,2

ACUTE INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

Acute primary angle-closure (glaucoma)

Acute primary angle-closure (APAC) is characterized by an acute impairment of the outflow of aqueous from the anterior chamber in an anatomically predisposed eye. This results in a rapid and severe elevation in IOP. Normal IOP lies between 10 and 21 mmHg, but in cases of APAC can rise to >60 mmHg. This is manifested as severe pain, blurring of vision and redness. The pain may be severe enough to cause nausea and vomiting, and may be poorly localized to the eye. Visual disturbance can be preceded by halos around lights, and in established cases is due to corneal oedema. Relative hypoxia of the pupillary sphincter due to elevated pressure results in a pupil unresponsive to light stimulation. The pupil is classically fixed and mid-dilated. The associated inflammation induces congestion of conjunctival and episcleral vessels. The term ‘acute angle-closure glaucoma’ is no longer regarded as appropriate, as there may be no optic nerve head cupping or visual field loss – the features that define glaucoma – at the acute presentation.

Early YAG laser PI in the affected eye may be hampered by corneal oedema. Argon laser peripheral iridoplasty may be used in the acute phase for resistant attacks, or where corneal oedema precludes YAG laser PI.3,4

Acute infectious keratitis

The most important aspect of management is to identify the infectious agent and to commence appropriate antibiotic treatment. A specimen is taken via a scraping for microbiological assessment, including Gram staining and culture. Under topical anaesthetic, using a preservative-free single-use dispenser of benoxinate or tetracaine (amethocaine), a sterile 23G needle is used to gather a small specimen. This is transferred directly to glass slides and also plated on to HB and chocolate agar plates for culture. Fungal cultures may be indicated. Antibiotic therapy is not delayed until the results are available, but is commenced on a broad-spectrum basis, such as the intensive use of a fluoroquinolone eye drop (e.g. G. ciprofloxacin) on an hourly basis. Daily monitoring with slit-lamp examination is mandatory and severe infections require hospital admission. This regimen can be modified when culture and sensitivity results are available. It is sometimes necessary to add a topical steroid when the active infection is under control, to limit the amount of inflammation and vascularization – and hence damage – to the cornea.

ACUTE VISUAL FAILURE

Introduction

Acute visual failure is any acute change in visual acuity, visual field or colour vision. Effective emergency management depends upon rapid recognition of those conditions for which acute therapy is available (Table 16.1.1). Some conditions have no effective therapy, or are more appropriately managed on an outpatient basis.

Table 16.1.1 Acute visual failure for which acute therapy is available

| Condition | Therapy |

|---|---|

| Central (or branch) retinal artery occlusion |

Clinical assessment

History

Particular attention should be paid to the rapidity of onset, degree and location in space of visual loss, previous episodes and associated symptoms. Most of the sinister causes of acute visual failure are painless (Table 16.1.2).

Table 16.1.2 Symptoms significant for cause in acute visual failure

| Symptom | Condition |

|---|---|

| Floaters (if recent onset) |

Examination

Testing of the visual acuity and visual field will clarify uni- or binocular involvement.

Bilateral vision loss

Bilateral acute, complete, visual failure is uncommon. Bilateral occipital infarction may present with bilateral blindness, but pupil responses would be expected to be intact. Rapidly progressive bilateral sequential visual loss from temporal arteritis is occasionally encountered. Other prechiasmal causes of bilateral, simultaneous, ocular involvement include toxic causes, such as poisoning with either quinine or methanol, where the patient presents with bilateral blindness and fixed, widely dilated pupils. Visual recovery in these cases is variable, and the efficacy of a range of therapeutic interventions is controversial.5–7

Central retinal artery occlusion

The history is typically of sudden, painless loss of vision in the affected eye over seconds. This may have been preceded by episodes of transient loss of vision (amaurosis fugax) in the previous days or weeks. Mean age of presentation is in the 60s. Men are more frequently affected, and the history may include evidence of previous cardiac or cerebrovascular disease. Systemic arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus are often coexistent. Carotid disease is frequently implicated, with emboli often being the cause of the obstruction, but their absence does not preclude the diagnosis, as the obstruction may lie behind the lamina cribrosa.

Intra-arterial fibrinolytic therapy is a promising technique that is not widely available at present and requires the services of an experienced interventional neuroradiology team.8–11 The place of hyperbaric therapy is uncertain at this time.12 The use of carbogen gas (95% oxygen/5% carbon dioxide) is now largely historical.

Central (branch) retinal vein occlusion

There is no emergency management specific to the vein occlusion that will positively influence the visual outcome, and the patient should therefore be referred to the next ophthalmic outpatient clinic. Systemic hypertension and raised IOP rarely require acute control.

Anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy

Clinical suspicion requires blood to be drawn for ESR and CRP. Treatment should then be started on an urgent basis and must not be delayed or deferred until after temporal artery biopsy. The biopsy will remain positive for at least several days despite steroids. Elevation of both ESR and CRP is highly specific for a diagnosis of GCA, but does not avoid the need for biopsy.13 Urgent referral to an ophthalmologist is required.

Prednisolone 1 mg/kg daily is an accepted dose, although recent experience has suggested that ‘pulse’ methylprednisolone 500 mg i.v. daily or twice daily over 1–2 h is safe and more efficacious in suppressing the inflammation, and this has become standard therapy in a number of centres. This is generally used for 3 days, and oral prednisolone is then substituted.14–16 Treatment will be prolonged (at least 6 months) and should be undertaken in cooperation with a physician. Attention should also be directed to the avoidance of steroid complications in this aged patient group.

Age-related macular degeneration

In 10–20% of cases of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), an exudative-type disease is seen, and in its most sinister form this will involve subretinal neovascularization (SRNV). These patients may present with painless distortion of vision, particularly metamorphopsia – a complaint that objects that they know to be straight appear curved. Visual acuity is reduced, depending on the stage of the disease; an RAPD is rarely seen owing to the relatively small area of retina involved, which manifests as a central scotoma on field testing. Macular drusen (yellow spots), retinal thickening and haemorrhage may be seen, with at least drusen usually also seen in the fellow eye.

Acute symptoms must not be dismissed. With appropriate treatment, central vision may be preserved in a proportion of these patients. Rapid ophthalmic review is therefore appropriate. Treatment will be undertaken following fundus fluorescein angiography to delineate the subretinal vascular lesion. Laser photocoagulation has been the traditional therapy, but the emergence of verteporfin, and more recently anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents such as ranibizumab (Lucentis) have revolutionized the treatment options and prognosis. Clinical trials with the anti-VEGF agents are ongoing.17,18

Optic neuritis

Good spontaneous recovery has made the value of treating optic neuritis controversial: the results of the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial19 would suggest that there is no place for oral prednisolone alone in management. The benefit of ‘pulse’ intravenous methylprednisolone seems restricted to shortening the acute episode, without influencing the possibility of progression to multiple sclerosis or the final visual outcome.20 However, there is usually no role for acute intervention, and referral within a day or two to a neurologist or an ophthalmologist is satisfactory.

1 McCarty CA, Fu CLH, Taylor HR. Epidemiology of ocular trauma in Australia. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1847-1852.

2 Colby K. Management of open globe injuries. International Opthalmologic Clinic. 1999;39:59-69.

3 Lai JSM, Tham CCY, Chua JK, et al. Laser peripheral iridoplasty as initial treatment of acute attack of primary angle-closure: A long-term follow-up study. Journal of Glaucoma. 2002;11:484-487.

4 Lam DSC, Lai JSM, Tham CCY, et al. Argon laser peripheral iridoplasty versus conventional systemic medical therapy as first line treatment of acute angle closure: a prospective, randomised controlled trial. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1591-1596.

5 Canning CR, Hague S. Ocular quinine toxicity. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 1988;72:23-26.

6 Bacon P, Spalton DJ, Smith SE. Blindness from quinine toxicity. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 1988;72:219-224.

7 Stelmach MZ, O’Day J. Partly reversible visual failure with methanol toxicity. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Ophthalmology. 1992;20:57-64.

8 Watson PG. The treatment of acute retinal arterial occlusion. In: Cant JS, editor. The ocular circulation in health and disease. St Louis: Mosby Year Book; 1969:243-245.

9 Schmidt D, Schumacher M, Wakhloo AK. Microcatheter urokinase infusion in central retinal artery occlusion. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1992;113:429-434.

10 Weber J, Remonda L, Mattle HP, et al. Selective intra-arterial fibrinolysis of acute central retinal artery occlusion. Stroke. 1998;29:2076-2079.

11 Beatty S, Au Eong KG. Local intra-arterial fibrinolysis for acute occlusion of the central retinal artery: a meta-analysis of the published data. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2000;84:914-916.

12 Beirna I, Reissman P, Scharf J, et al. Hyperbaric oxygenation combined with nifedipine treatment for recent-onset retinal arterial occlusion. European Journal of Ophthalmology. 1993;3:89. 84

13 Hayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Raman R, et al. Giant cell arteritis: validity and reliability of various diagnostic criteria. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1997;123:285-296.

14 Hayreh SS. Anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy. Differentiation of arteritic from non-arteritic type and its management. Eye. 1990;4:25-41.

15 Liu GT, Glaser JS, Schatz NJ, et al. Visual morbidity in giant cell arteritis. Clinical characteristics and prognosis for vision. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:1779-1785.

16 Cornblath WT, Eggenberger ER. Progressive visual loss from giant cell arteritis despite high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:854-858.

17 Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, et al. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355:1419-1431.

18 Brown DM, Kaiser PK, Michels M, et al. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355:1432-1444.

19 Beck RW, Cleary PA, Anderson MA, et al. A randomized controlled trial of corticosteroids in the treatment of acute optic neuritis. New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;326:581-588.

20 Kapoor R, Miller DH, Jones SJ, et al. Effects of intravenous methylprednisolone on outcome in MRI-based prognostic subgroups in acute optic neuritis. Neurology. 1998;50:230-237.

Kanski J. Clinical Ophthalmology. A systematic approach, 6th edn. Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd, Oxford, 2007. (rev)

The Wills eye manual. Office and emergency room diagnosis and treatment of eye disease, 4th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2004. (rev)

Riordan-Eva P. Vaughan and Asbury’s general ophthalmology, 16th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2003.