CHAPTER 16 Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, Behavioral Therapy, and Cognitive Therapy

OVERVIEW

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the most extensively researched forms of psychotherapy and is increasingly recognized as the treatment of choice for many disorders.1 Findings from randomized controlled trials typically suggest that CBT is better than wait-list control groups, as well as supportive treatment and other credible interventions, for specific disorders. Early implementations of CBT were largely indicated for anxiety and mood disorders.2 However, more recent clinical research efforts have begun to develop CBT for an increasingly wider array of problems (including bipolar disorder,3 eating disorders,4 attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder,5 and psychotic disorders6).

The empirical evidence for the use of CBT for a broad range of conditions is promising.7 However, there remains a noticeable gap between encouraging reports from clinical trials and the widespread adoption of CBT interventions among general practitioners.8 Moreover, questions remain regarding the limits of and indications for the efficacy of CBT in general practice.9 Nevertheless, it is clear that CBT interventions represent the best of what the psychotherapy community currently has to offer in terms of evidence-supported treatment options.

CBT generally refers to a treatment that uses behavioral and cognitive interventions; it is derived from scientifically supported theoretical models.10,11 Thus, there exists a theoretically consistent relationship between CBT treatment techniques and the disorders that they are designed to treat.12 Depending on the disorder, interventions may be directed toward eliminating cognitive and behavioral patterns that are directly linked to the development or maintenance of the disorder, or they may be directed toward maximizing coping skills to address the elicitation or duration of symptoms from disorders driven by other (e.g., biological) factors.

BEHAVIORAL THERAPY, COGNITIVE THERAPY, AND COGNITIVE-BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

Cognitive-behavioral therapies represent an integration of two strong traditions within psychology: behavioral therapy (BT) and cognitive therapy. BT refers to any of a large number of specific techniques that employ principles of learning to change human behavior. These techniques include exposure, relaxation, assertion training, social skills training, problem-solving training, modeling, contingency management, and behavioral activation. Many of these interventions are a direct outgrowth of principles of operant and respondent conditioning. Operant conditioning is concerned with the modification of behaviors by manipulation of the rewards and punishments, as well as the eliciting events. For example, in the treatment of substance dependence, the use of specific contingencies between drug abstinence (as frequently confirmed by urine or saliva toxicology screens) and rewards (e.g., the chance to win a monetary reward) has proven to be a powerful strategy for achieving abstinence among chronic drug abusers.13 Included as an operant strategy are also the myriad of interventions that use stepwise train-ing to engender needed new skills for problem situations. For example, assertiveness training, relaxation training, and problem-solving training are all core behavioral strategies for intervening with skill deficits that may be manifest in disorders as diverse as depression, bipolar disorder, or hypochondriasis. One approach to treating depression, for example, has emphasized the return to pleasurable and productive activities, and the specific use of these activities to boost mood. Interventions involve the step-by-step programming of activities rated by patients as relevant to their personal values and likely to evoke pleasure or a sense of personal productivity. Behavioral activation will typically consist of construction of an activity hierarchy in which up to (approximately) 15 activities are rated ranging from easiest to most difficult to accomplish. The patient then moves through the hierarchy in a systematic manner, progressing from the easiest to the most difficult activity.14 Depending on the patient, additional interventions or skill development may be needed. For example, assertion training may include a variety of interventions such as behavioral rehearsal, which is acting out appropriate and effective behaviors, to manage situations in which assertiveness is problematic.

Respondent conditioning refers to the changing of the meaning of a stimulus through repeated pairings with other stimuli, and respondent conditioning principles have been particularly applied to interventions for anxiety disorders. For example, influential theories such as Mowrer’s15 two-factor theory of phobic disorders emphasized the role of respondent conditioning in establishing fearful responses to phobic cues, and the role of avoidance in maintaining the fear. Accordingly, BT focuses on the role of exposure to help patients re-enter phobic situations and to eliminate (extinguish) learned fears about these phobic stimuli through repeated exposure to them under safe conditions. Exposure treatments may include any number of modalities or procedures. For example, a patient with social phobia may be exposed to a series of social situations that elicit anxiety, including in vivo exposure (e.g., talking on the phone, talking with strangers, giving a speech), imaginal exposure (e.g., imagining themselves in a social situation), exposure to feared sensations (termed interoceptive exposure because exposure involves the elicitation of feared somatic sensations, typically sensations similar to those of anxiety and panic), and exposure to feared cognitions (e.g., exposure to feared concepts using imaginal techniques). Exposure is generally conducted in a graduated fashion, in contrast to flooding, in which the person is thrust into the most threatening situation at the start. Exposure is designed to help patients learn alternative responses to a variety of situations by allowing fear to dissipate (become extinguished) while remaining in the feared situation. Once regarded as a passive weakening of learned exposures, extinction is now considered an active process of learning an alternative meaning to a stimulus (e.g., relearning a sense of “safety” with a once-feared stimulus),16 and ongoing research on the principles, procedures, and limits of extinction as informed by both animal and human studies has the potential for helping clinicians further hone in on the efficacy of their exposure-based treatments. For example, there is increasing evidence that the therapeutic effects of exposure are maximized when patients are actively engaged in and attentive to exposure-based learning; when exposure is conducted in multiple, realistic contexts; and when patients are provided with multiple cues for safety learning.17 Therapists should also ensure that the learning that occurs during exposure is independent of contexts that will not be present in the future (e.g., in the presence of the therapist). Effective application of exposure therapy also requires prevention of safety behaviors that may undermine what is learned from exposure. Safety behaviors refer to those behaviors that individuals may use to reassure themselves in a phobic situation. For example, a patient with panic disorder may carry a cell phone or a water bottle for help or perceived support during a panic attack. These safety behaviors, while providing reassurance to patients, appear to block the full learning of true safety.18,19 That is, when such safety behaviors are made unavailable, better extinction (safety) learning appears to result.20,21

Cognitive therapy was initially developed as a treatment for depression with the understanding that thoughts influence behavior and it is largely maladaptive thinking styles that lead to maladaptive behavior and emotional distress.22,23 Currently, however, cognitive therapy includes approaches to a wider range of disorders.24,25

As applied to depression, the cognitive model posits that intrusive cognitions associated with depression arise from a synthesis of previous life experiences. The synthesis of such experiences is also described as a schema, a form of semantic memory that describes self-relevant characteristics. For example, the cognitive model of depression posits that negative “schemas” about the self that contain absolute beliefs (e.g., “I am unlovable” or “I am incompetent”) may result in dysfunctional appraisals of the self, the world, and the future. On exposure to negative life events, negative schemas and dysfunctional attitudes are activated that may produce symptoms of depression. Thus, maladaptive cognitive patterns and negative thoughts may also be considered risk or maintaining factors for depression.26 Negative automatic thoughts can be categorized into a number of common patterns of thought referred to as cognitive distortions. As outlined in Table 16-1, cognitive distortions often occur automatically and may manifest as irrational thoughts or as maladaptive interpretations of relatively ambiguous life events.

| Distortion | Description |

|---|---|

| All-or-nothing thinking | Looking at things in absolute, black-and-white categories |

| Overgeneralization | Viewing negative events as a never-ending pattern of defeat |

| Mental filter | Dwelling on the negatives and ignoring the positives |

| Discounting the positives | Insisting that accomplishments or positive qualities “don’t count” |

| Jumping to conclusions | Mind reading (assuming that people are reacting negatively to you when there’s no evidence to support the assumptions) |

| Fortune-telling (arbitrarily predicting that things will turn out badly) | |

| Magnification or minimization | Blowing things out of proportion or shrinking their importance inappropriately |

| Emotional reasoning | Reasoning from how you feel (“I feel stupid, so I must really be stupid”) |

| “Should” statements | Criticizing yourself (or others) with “shoulds” or “shouldn’ts,” “musts,” “oughts,” and “have-tos” |

| Labeling | Identifying with shortcomings (“I’m a loser”) |

| Personalization and blame | Blaming yourself for something you weren’t entirely responsible for |

Adapted from Beck JS: Cognitive therapy: basics and beyond, New York, 1995, Guilford Press.

Cognitive therapy,27 and a similar approach known as rational-emotive therapy,28 provides techniques that correct distorted thinking and offer a means by which patients can respond to maladaptive thoughts more adaptively. In addition to examining cognitive distortions (see Hollon and Garber29 and Table 16-1), cognitive therapy focuses on more pervasive core beliefs (e.g., “I am unlovable” or “I am incompetent”) by assessing the themes that lie behind recurrent patterns of cognitive distortions. Those themes may be evaluated with regard to a patient’s learning history (to assess the etiology of the beliefs with the goal of logically evaluating and altering the maladaptive beliefs).

A commonly used cognitive technique is cognitive restructuring. Cognitive restructuring begins by teaching a patient about the cognitive model and by providing a patient with tools to recognize (negative) automatic thoughts that occur “on-line” (most therapists use a daily log or a diary to monitor negative automatic thoughts). The next step in cognitive restructuring is to provide the patient with opportunities to evaluate his or her thoughts with respect to their usefulness, as well as their validity. Through the process of logically analyzing thoughts, a patient is provided with a unique context for replacing distorted thoughts with more accurate and realistic thoughts. One method for helping a patient engage in critical analysis of thinking patterns is to consider the objective evidence for and against the patient’s maladaptive thoughts. Thus, questions such as, “What is the evidence that I am a bad mother? What is the evidence against it?” might be asked. Another useful technique places the patient in the role of adviser (this is often referred to as the double-standard technique27). In the role of adviser, a patient is asked what advice he or she might give a family member or friend in the same situation. By distancing the patient from his or her own maladaptive thinking, the patient is given the opportunity to engage in a more rational analysis of the issue. These techniques allow patients to test the validity and utility of their thoughts; as they evaluate their thinking and see things more rationally, they are able to function better. In addition to techniques for changing negative thinking patterns, cognitive therapy also incorporates behavioral experiments. Behavioral tasks and experiments are employed in cognitive therapy to provide corrective data that will challenge beliefs and underlying negative assumptions.

Concerning the mechanism of relapse prevention in cognitive therapy, there is growing attention to the importance of the processing and form of negative thoughts, not just their content.30,31 Studies suggest that cognitive interventions may be useful for helping patients gain perspective on their negative thoughts and feelings so that these events are not seen as “necessarily valid reflections of reality” (Teasdale et al.,30 p. 285). Indeed, there is evidence that changes in metacognitive awareness may mediate the relapse prevention effects of cognitive therapy.30,32 Accordingly, shifting an individual’s emotional response to cognitions may be an important element of the strong relapse prevention effects associated with cognitive therapy.33

Although cognitive therapy was initially developed to focus on challenging depressive distortions, basic maladaptive assumptions are also observed in a wide range of other conditions, with the development of cognitive therapy approaches ranging from panic disorder,34 posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD),35 social phobia,36 and hypochondriasis,25 to personality disorders24 and the prevention of suicide.37

PUTTING BEHAVIORAL THERAPY AND COGNITIVE THERAPY TOGETHER

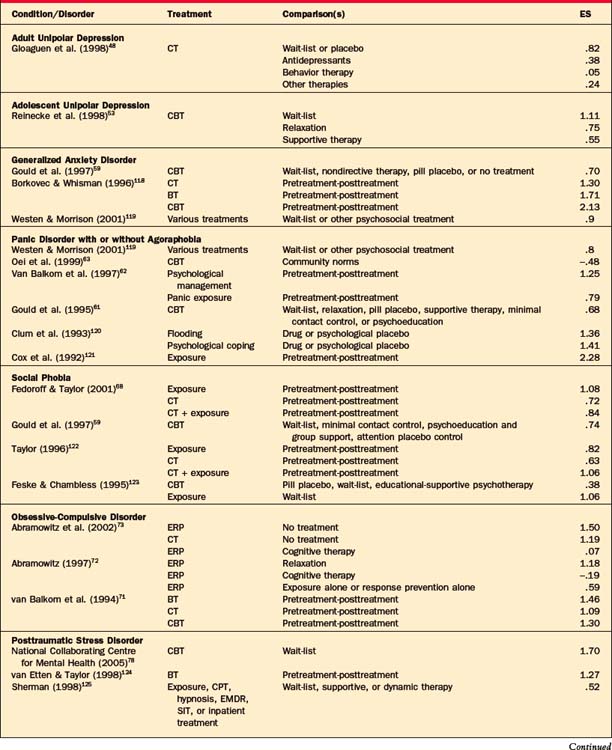

As a functional unification of cognitive and behavioral interventions, CBT relies heavily on functional analysis of interrelated chains of thoughts, emotions, and behavior. Thus, the principles that underlie CBT are easily exportable to a wide range of behavioral deficits. As outlined in Table 16-2,38 cognitive therapy, behavioral therapy, and their combination have garnered empirical support for the treatment of a wide range of disorders. CBT has become increasingly specialized in the last decade, and advances in the conceptualization of various disorders have brought a refinement of CBT interventions to target core features and dominant behavior patterns that characterize various disorders.

Table 16-2 Examples of Well-Established Cognitive, Behavioral, and Cognitive-Behavioral Treatments for Specific Disorders

| Treatment | Condition/Disorder |

|---|---|

| Cognitive | Depression |

| Behavioral | Agoraphobia |

| Depression | |

| Social phobia | |

| Specific phobia | |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | |

| Headache | |

| Oppositional behavior | |

| Enuresis | |

| Marital dysfunction | |

| Female orgasmic dysfunction | |

| Male erectile dysfunction | |

| Developmental disabilities | |

| Cognitive-behavioral | Panic, with and without agoraphobia |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | |

| Social phobia | |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | |

| Chronic pain | |

| Bulimia |

Adapted from Chambless DL, Baker MJ, Baucom DH, et al: Update on empirically validated therapies: II, Clin Psychol 51:3-16, 1998.

Basic Principles of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

As outlined in Table 16-3, contemporary CBT is a collaborative, structured, and goal-oriented intervention.1 Current forms of CBT target core components of a given disorder. For example, CBT interventions for panic disorder target catastrophic misinterpretations of somatic sensations of panic and their perceived consequences, while exposure procedures focus directly on the fear of somatic sensations. Likewise, CBT for social phobia focuses on the modification of fears of a negative evaluation by others and exposure treatments emphasize the completion of feared activities and interactions with others. For generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), CBT treatment focuses on the worry process itself, with the substitution of cognitive restructuring and problem solving for self-perpetuating worry patterns, and the use of imaginal exposure for worries and fears. In the case of depression, CBT targets negative thoughts about the self, the world, and the future, as well as incorporating behavioral activation to provide more opportunities for positive reinforcement. Symptom management strategies (e.g., breathing retraining or muscle relaxation) or social skills training (e.g., assertiveness training) are also valuable adjuncts to exposure and to cognitive restructuring interventions.

Table 16-3 Characteristic Features of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| CBT is short-term | The length of therapy in CBT is largely dependent on the time needed to help the patient develop more adaptive patters of responding. However, CBT treatments generally involve approximately 8 to 20 sessions. |

| CBT is active | CBT provides a context for learning adaptive behavior. It is the therapist’s role to provide the patient with the information, skills, and opportunity to develop more adaptive coping mechanisms. Thus, homework is a central feature of CBT. |

| CBT is structured | CBT is agenda-driven such that portions of sessions are dedicated to specific goals. Specific techniques or concepts are taught during each session. However, each session should strike a balance between material introduced by the patient and the predetermined session agenda. |

| CBT is collaborative | The therapeutic relationship is generally less of a focus in CBT. However, it is important that the therapist and patient have a good collaborative working relationship in order to reduce symptoms by developing alternative adaptive skills. |

CBT, Cognitive-behavioral therapy.

The Basic Practice of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

In many approaches to CBT, patient and therapist collaboratively set an agenda for topics to be discussed in each session. Particular attention is given to events that occurred since the previous session that are relevant to the patient’s goals for treatment. Part of the agenda for treatment sessions should focus on the anticipation of difficulties that may occur before the next treatment session. These problems should then be discussed in the context of problem-solving and the implementation of necessary cognitive and behavioral skills. This may require training in skills that readily facilitate the reduction of distress. Skills, such as training in diaphragmatic breathing and progressive muscle relaxation, can be particularly useful in this regard. Although the specific interventions used during CBT may vary, the decision on which interventions to use should be informed by cognitive and learning theories that view disorders as understandable within a framework of reciprocally connected behaviors, thoughts, and emotions that are activated and influenced by environmental and interpersonal events.

As indicated in Table 16-3, CBT is also an active treatment with an emphasis on home practice of interventions. Thus, review of homework is a major component of the CBT session. In reviewing the patient’s homework, emphasis should be placed on what the patient learned, and what the patient wants to continue doing during the coming week for homework. The homework assignment, which is collaboratively set, should follow naturally from the problem-solving process in the treatment session. The use of homework in CBT draws from the understanding of therapy as a learning experience in which the patient acquires new skills. At the end of each CBT treatment session, a patient should be provided with an opportunity to summarize useful interventions from the session. This should also consist of asking the patient for feedback on the session, and efforts to enhance memories of and the subsequent home application of useful interventions.39

Relapse prevention skills are central to CBT as well. By emphasizing a problem-solving approach in treatment, a patient is trained to recognize the early warning signs of relapse and is taught to be “his or her own therapist.” Even after termination, a patient often schedules “booster sessions” to review the skills learned in treatment. In addition, novel approaches to relapse prevention, as well as treatment of residual symptoms, emphasize the application of CBT to the promotion of well-being rather than simply the reduction of pathology.40,41

The Practice of CBT: The Case of Panic Disorder

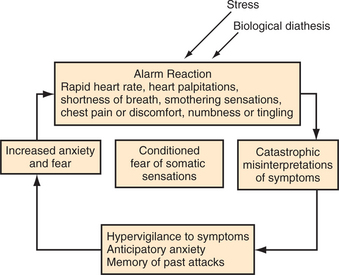

CBT for panic disorder generally consists of 12 to 15 sessions; it begins with an introduction of the CBT model of panic disorder (Figure 16-1).42 The therapist begins by discussing the symptoms of panic with the patient. It is explained that the symptoms of panic (e.g., rapid heart rate, shortness of breath, and trembling) are part of our body’s natural defense system that prepares us for fight or flight in the presence of a real threat. When these symptoms occur in the presence of a real danger, the response helps us survive. When the symptoms occur in the absence of a real danger, the response is a panic attack. Often when a person experiences a panic attack “out of the blue,” he or she fears that something is terribly wrong. The person fears that he or she may be having a heart attack, may be seriously ill, or may be “going crazy.” It is explained to the patient that these catastrophic misinterpretations of the symptoms of panic disorder serve to maintain the disorder. The interpretation causes the individual to fear another attack; as a consequence, the person becomes hypervigilant for any somatic sensations that may signal the onset of an attack. This hypervigilance, in turn, heightens the individual’s awareness of his or her body and increases somatic sensations that lead to more anxiety. This cycle continues, culminating in a panic attack.

Figure 16-1 Cognitive-behavioral model of panic disorder.

(Adapted from Otto MW, Pollack MH, Meltzer-Brody S, Rosenbaum JF: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for benzodiazepine discontinuation in panic disorder patients, Psychopharmacol Bull 28:123-130, 1992.)

Over the course of treatment, the therapist works with the patient to examine the accuracy of catastrophic misinterpretations through Socratic questioning and provision of corrective information. For example, the patient may be asked to evaluate the evidence for all of the likely consequences of a panic attack. Additionally, the patient is gradually exposed to the somatic sensations that he or she fears (a process called interoceptive exposure). Interoceptive exposure consists of a wide variety of procedures (such as hyperventilation, exercise, or spinning in a chair43) meant to expose a patient to feared internal bodily experiences (e.g., tachycardia, numbness, or tingling) in a controlled fashion. Through repeated exposure to these sensations, a patient habituates to the sensations, which results in a decrease in fear and anxiety linked to internal stimuli. With repeated exposure, a patient learns that the sensations are not harmful.

Cognitive restructuring is combined with interoceptive exposure to aid the patient in reinterpreting the somatic sensations and reducing fear. For a patient with agoraphobia, gradual situational exposure is also conducted to eliminate avoidance of situations that have been associated with panic. In all exposure exercises, special attention must be paid to the elimination of safety behaviors that may interfere with habituation to the fear and extinction learning. Safety behaviors include anything that the patient may do to avoid experiencing anxiety. This could include carrying a bottle of pills in the patient’s pocket or having a cell phone with the patient to call for help. To maximize the exposure exercises, these behaviors must be gradually eliminated. The patient must learn that he or she will be okay even in the absence of such behaviors. The use of relaxation techniques for the treatment of panic may also be beneficial. However, Barlow and associates44 found that adding relaxation to the treatment (emphasizing cognitive restructuring and interoceptive exposure) appeared to reduce the efficacy of the treatment over time (see also Schmidt et al.45). This suggests that in some cases, a patient may engage in relaxation as a safety technique (i.e., a patient may rely too much on relaxation as a panic management technique at the expense of learning not to be afraid of anxiety-related sensations). Although relaxation techniques may come to serve the function of avoidance for some patients with panic disorder, studies have shown that relaxation strategies offer some benefit to patients with a wide range of anxiety disorders.46 Thus, the decision to offer relaxation techniques in CBT for patients with panic disorder should be informed by the context in which the patient will apply such techniques.

THE EFFICACY OF COGNITIVE-BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

As outlined in Table 16-1, cognitive and behavioral techniques and their combination (CBT) are generally considered as empirically supported interventions for a wide range of disorders. In fact, numerous outcome trials have demonstrated that CBT is effective for a host of psychiatric disorders, as well as for medical disorders with psychological components.47 However, diagnostic co-morbidity, personality disorders, or complex medical problems may complicate CBT treatment. Such complications do not imply that a patient will not respond well to CBT, but rather that the patient might have a slower response to treatment.

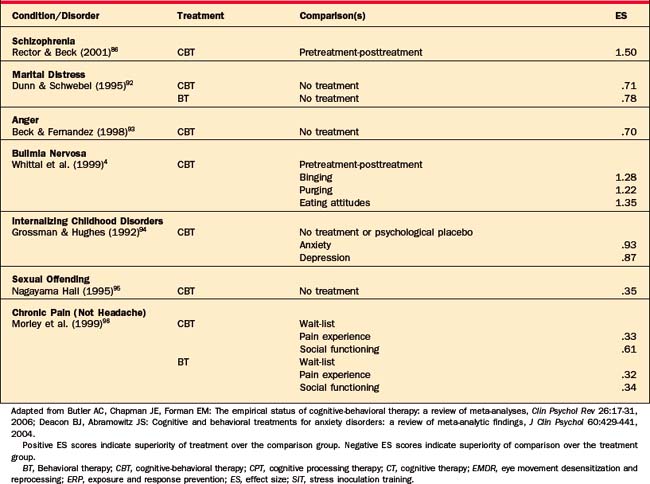

In an attempt to integrate findings from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), multiple meta-analytic studies (which allow researchers to synthesize quantitatively the results from multiple studies in an effort to characterize the general effectiveness of various interventions) have been conducted. Two recent reviews of the most comprehensive meta-analyses conducted for the efficacy of CBT have nicely summarized the treatment outcome effect sizes for adult unipolar depression, adolescent depression, GAD, panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), PTSD, schizophrenia, marital distress, anger, bulimia, internalizing childhood disorders, sexual offending, and chronic pain (excluding headache).7,12 A review of these meta-analyses and other relevant findings is presented next and summarized in Table 16-4.

Table 16-4 Summary of Meta-Analyses of Studies Examining the Efficacy of Cognitive and Behavioral Therapies

Adult Unipolar Depression

Cognitive therapy has been most extensively studied in adult unipolar depression. In a comprehensive review of the treatment outcomes, Gloaguen and colleagues48 found cognitive therapy to be better than (1) being on a wait-list or being placed on a placebo, (2) antidepressant medications, and (3) other miscellaneous therapies. It was also as efficacious as BT. Although a change in cognitive schemas and automatic negative thoughts has long been thought of as the central mechanism through which cognitive therapy results in improvement, this has been called into question by the success of behavioral treatments of depression. In an investigation of the relative efficacy of individual components of cognitive therapy, it was found that the behavioral components of cognitive therapy resulted in as much acute improvement and prevention of relapse as was the full cognitive therapy treatment.49,50 Since these findings emerged, researchers have worked to refine and to develop the behavioral components into a treatment called behavioral activation (BA) (which abandons the cognitive components of treatment in favor of behavioral techniques aimed at encouraging positive activities, engaging with the environment, and reducing avoidance).

A recent trial comparing BA with cognitive therapy and antidepressants found that BA was as effective as antidepressant medication and more effective than cognitive therapy at reducing the symptoms of depression.51 The success of this treatment is a promising development in the treatment of depression because the techniques used in BA are much more easily learned by clinicians. The ease by which BA is learned by clinicians may facilitate its dissemination to settings (i.e., primary care, community mental health settings) where quick, easy, and effective treatments for depression are needed.

The evidence for long-term efficacy of CBT for adult unipolar depression is also promising. Patients treated to remission with cognitive therapy are approximately half as likely to relapse as are patients who are treated to remission with antidepressant medications.52 Cognitive therapy has also been shown to be superior to antidepressants at preventing recurrence of major depression following the discontinuation of treatment.33

Adolescent Unipolar Depression

The importance of treatment and prevention of psychiatric illness in children and adolescents has been increasingly recognized. Although treatment of children and adolescents is often complicated by developmental considerations, positive results have been reported in the treatment of adolescent unipolar depression. Reinecke and colleagues’ review of CBT for adolescents with major depression53 found CBT to be superior to wait-list, relaxation training, and supportive therapy (with effect sizes ranging from .45 to 1.12). Butler et al.7 noted, however, that the sample sizes are small in this area of research and the findings should be interpreted with caution and treated as preliminary at best.

Bipolar Disorder

In the last decade, there has been a striking increase in the application of psychosocial treatment as an adjunctive strategy to the pharmacological management of bipolar disorder. Cognitive-behavioral approaches have been prominent among these innovations,3 with clear evidence that interest in, and acceptance of, an important role for psychosocial treatment is rising among experts in bipolar disorder.54 The treatment literature has progressed from initial CBT protocols aimed at improving medication adherence55 to broader protocols that are targeted toward relapse prevention, as well as the treatment of bipolar depression. These broader CBT protocols, which include psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, problem-solving skills, and sleep and routine management, have reduced manic, hypomanic, and depressive episodes and resulted in fewer days spent in a mood episode and in shorter lengths of hospital stays.56–58 The management of bipolar disorder is an excellent example of when CBT can be a very effective supplement to medication.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

A meta-analysis by Gould et al.59 revealed that CBT was superior to wait-list and to no-treatment conditions and equally as effective as medication in the treatment of GAD. The authors also compared the effect sizes for CBT, BT, and cognitive therapy and found that CBT resulted in an effect size of .91, whereas for cognitive therapy alone the effect size was .59 and for BT alone it was .51. Therefore, the optimal treatment for GAD appears to consist of both cognitive and behavioral components. Gains achieved via long-term treatment of GAD (through CBT) have also been reported. In a comparison of CBT, dynamic psychotherapy, and medication, Durham and co-workers60 found that CBT for GAD resulted in the most enduring improvement 8 to 14 years after treatment.

Panic Disorder

CBT is also efficacious for panic disorder. In a meta-analysis by Gould and colleagues,61 CBT was found to be superior to wait-list and placebo; treatments composed of cognitive restructuring and interoceptive exposure resulted in the greatest improvements (d = .88). Similarly, a meta-analysis by van Balkom and colleagues62 revealed that BT consisting of in vivo exposure was very effective for the treatment of panic (d = .79) and agoraphobia (d = 1.38). In a comparison between community norms and patients with panic disorder (treated with cognitive therapy),63 cognitive therapy reduced symptoms (to normal levels) by the end of treatment. CBT also results in more enduring treatment gains when compared with medication treatment.64–66

Social Anxiety Disorder

CBT has also been effective for reducing social anxiety. A meta-analysis by Gould and colleagues67 demonstrated that CBT was superior to wait-list and to placebo with an effect size of .93. The pretreatment-to-posttreatment effect sizes for CBT, cognitive therapy, and BT were found to be .80, .60, and .89, respectively. A second meta-analysis examining the efficacy of CBT, cognitive therapy, and BT found effect sizes of .84, .72, and 1.08, respectively.68 Taken together, these findings suggest that cognitive and behavioral interventions are effective for social anxiety disorder. Furthermore, it appears that the elements of BT (i.e., exposure) may be responsible for the majority of the treatment gains observed in social anxiety disorder. Moreover, CBT (for social anxiety disorder) results in more long-lasting treatment effects when compared with medication.69,70

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

A meta-analysis by Van Balkom and colleagues71 examined pretreatment-to-posttreatment effect sizes for BT (exposure response prevention [EPR] and other exposure-based treatments), cognitive therapy (cognitive techniques in the absence of any exposure), and CBT (treatments combining both cognitive techniques and exposure) for OCD. The clinician-rated effect sizes were found to be 1.47, 1.04, and 1.85, respectively, suggesting that all three treatments were effective and that the addition of cognitive techniques to BT may result in additional gains. In another meta-analysis that compared cognitive therapy directly to ERP, cognitive therapy was found to be slightly more effective.72 However, a third meta-analysis73 revealed that ERP had a stronger effect size than cognitive therapy when both were compared to a no-treatment group. However, when the two treatments were directly compared against each other, they were found to be equally effective. Taken together these results suggest that cognitive therapy, CBT, and BT (ERP) are effective treatments for OCD. Cognitive therapy may prove to be an effective and more tolerable treatment alternative.74,75 CBT also shows long-term efficacy for OCD.76,77

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Considerable evidence supports the efficacy of CBT for PTSD. A recent meta-analysis of psychological treatments for PTSD revealed that CBT was superior to a wait-list condition (with a mean effect size of 1.49),78 and CBT is considered a first-line treatment according to a 2000 consensus statement.79 Well-controlled trials have consistently shown benefit for CBT over control conditions, with support for treatments emphasizing imaginal or in vivo exposure to trauma cues, as well as those emphasizing cognitive restructuring in the context of repeated exposure to accounts of the trauma.80–84 Cognitive-behavioral approaches share a focus on helping patients systematically reprocess the traumatic event and reduce the degree to which cues associated with the trauma are capable of inducing strong emotional responses, typically through a combination of exposure and cognitive-restructuring interventions. There is also evidence to support the long-term efficacy of CBT for PTSD.85

Schizophrenia

CBT has been found to be effective as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy in the treatment of schizophrenia. One review revealed that CBT plus routine care was shown to reduce positive, negative, and overall symptoms (d = 1.23).86 Those treated only with routine care showed modest symptom improvements, over the same period (d = .17). Additionally, CT may be effective as a prevention strategy in individuals at ultra-high risk of developing the disorder.87

Eating Disorders

CBT is a first-line treatment of choice for bulimia nervosa.88 Meta-analytic review of CBT for bulimia indicates clinically significant reductions in binging frequency (d = 1.28), purging frequency (d = 1.22), and improvements in eating attitudes (d = 1.35) from pretreatment to posttreatment.4 CBT also compares well to other treatments, with equal or greater efficacy to medications89 and other relevant alternative treatments.90,91

Substance Dependence

A range of cognitive-behavioral approaches have been repeatedly found to be effective for treating substance use disorders. These interventions prominently include contingency management techniques (where social, monetary, or other voucher rewards are provided contingent on negative toxicology screens for substance use), skill acquisition and relapse prevention approaches (where responses for avoiding or coping with high-risk situations for drug use are identified and rehearsed, as are alternative nondrug behaviors), and behavioral family therapy (where contingency management, interpersonal support, and skill-building interventions might be combined) (for a review, see Carroll and Onken13). Despite the success of these approaches, treatment of drug dependence is an area in great need of additional strategies for boosting treatment response and the maintenance of treatment gains.

Other Psychological Conditions

When compared to no treatment, CBT has been found to be effective in reducing marital distress (d = .71), although it was not significantly more effective than behavioral marital therapy or interpersonally oriented marital therapy.92 A similar effect size has been reported for CBT for anger and aggression when compared to no treatment (d = .70).93 In a meta-analysis examining the efficacy of CBT for childhood internalizing disorders, Grossman and Hughes94 found that CBT, when compared to no treatment or to psychological placebo, resulted in significant improvements in anxiety (d = .93), depression (d = .87), and somatic symptoms (d = .47). More modest treatment effects have been reported for CBT for other psychological conditions. For example, in a review of CBT for sexual offending, Nagayama Hall95 found an overall effect size of .35 on measures of recidivism when compared with no treatment. A meta-analysis of CBT for pain revealed effect sizes that ranged from −.06 on measures of mood to .61 on measures of social role functioning, and on direct measures of the experience of pain, CBT was found to have an effect size of .33.96

The Effectiveness of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

A common concern is whether the results found in well-controlled RCTs of CBT translate well to routine practice in the community.97 Relative to this concern, Westbrook and Kirk98 recently published a large outcome study examining the effectiveness of CBT for 1,276 patients in a free mental health clinic. They found that of 1,276 patients who started treatment, 370 dropped out before the agreed-on end of treatment. This is a higher dropout rate than is usually reported in clinical trials of CBT; however, the authors did not provide information regarding reason for dropout, which makes interpretation of this finding difficult. Because the patients in the clinic were not reliably diagnosed using a structured clinical interview, the authors relied on two measures as their outcome variables for all patients: the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). For treatment completers, the overall effect size for pretreatment-to-posttreatment improvement was .52 on the BAI and .67 on the BDI. When the authors examined only those individuals who entered treatment with a score in the clinical range on either of these measures, the pretreatment-to-posttreatment effect sizes rose to .94 and 1.15, respectively. These findings are consistent with indications that clinical practice frequently encounters patients who are less severe than those in clinical trials99 and supports the efficacy of CBT in the community setting for a wide range of psychiatric disorders. Additionally, these results are very similar to other effectiveness and benchmarking trials,100–103 suggesting that these are fairly reliable and representative outcomes for care in the community.

COMBINING COGNITIVE-BEHAVIORAL THERAPY WITH MEDICATION

Psychiatric medications are commonly considered the first line of treatment for a wide range of psychiatric disorders. However, pharmacotherapy may not produce a complete remission of symptoms and at times may be associated with a delayed effectiveness. CBT can complement, if not replace, pharmacotherapy for various disorders. CBT can be offered to patients to control symptoms while awaiting a response to medications and to supplement or strengthen treatment response. Indeed, CBT has also been shown to be an effective treatment in addition to medication for chronic mental illnesses (such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia).104 These findings seem to support the notion that two treatments (CBT plus pharmacotherapy) must be better than one. However, a recent examination of the treatment outcome literature has revealed that the question of whether or not to combine pharmacotherapy and CBT may not be straightforward.105 The decision to provide combined treatment must include a careful examination of the disorder, the severity and chronicity of the disorder, the patient’s treatment history, and the stage of treatment.

For unipolar depression it appears that combining medication and CBT results in a slight advantage over either treatment alone.52,105 However, the advantage of combined treatment is most pronounced for individuals with severe or chronic depression. CBT has been effective at preventing relapse in individuals who have already responded to antidepressants and wish to discontinue the medication. In this case, medication and CBT would be delivered in a sequential rather than simultaneous manner. Hollon and colleagues52 suggest that CBT and pharmacotherapy may complement each other due to their different rates of change. Pharmacotherapy is typically associated with a more rapid initial change, whereas CBT has been associated with improvements slightly later, after the initiation of treatment. Thus, individuals receiving both types of treatment benefit from the early boost of medication and the later improvements associated with CBT. CBT and medication for depression may also complement each other in their mechanisms of change in the brain. Treatment of depression with CBT operates through the medial frontal and cingulate cortices to effect change in the prefrontal hippocampal pathways.106 Treatment with paroxetine (a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor [SSRI]) also produced changes in the prefrontal hippocampal pathways, but through the brainstem, insula, and subgenual cingulate. Thus, CBT and medication may operate through different pathways to reach the same result. However, some of the unique advantages of CBT compared to medication for depression are as follows107:

The decision to provide combined treatment for anxiety disorders involves even more complications. A recent review of the treatment for panic disorder suggests that combined treatment is associated with modest short-term gains over each modality alone for panic disorder. However, in analysis of long-term outcome, combined treatment remained superior to medication alone, but was not more effective than CBT alone.108 The results of a multicenter study investigating combination treatments for social anxiety disorder (CBT alone, fluoxetine alone, the combination of these treatments, or placebo) revealed that there was less than a 3% improvement in response rates for the addition of fluoxetine to CBT; patients treated with CBT plus fluoxetine demonstrated a response rate of 54.2% relative to a response rate of 51.7% for CBT alone, and a response rate of 50.8% for fluoxetine alone.109 Similar findings were reported in a multicenter study of combination treatment for OCD.110 Outcomes for patients who received combined CBT (exposure and response prevention) and clomipramine were not significantly better than for patients who received CBT alone, and both of these groups achieved a better outcome than those treated with clomipramine alone.

Thus, it appears that combining medication and CBT for anxiety disorders may not result in treatment gains substantially greater than those achieved through CBT alone. Considering that CBT is a more cost-effective treatment than is use of medication,111 practitioners should consider CBT as a first-line treatment for the anxiety disorders, with pharmacotherapy as an alternative treatment for CBT nonresponders. The addition of CBT to medication, however, is beneficial. There is also evidence that the addition of CBT during and after medication discontinuation enables patients to maintain treatment gains.112 More recent developments in combination treatment have examined augmenting CBT with glutamatergic N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) agonists (such as d-cycloserine). This approach stems from animal research that has implicated NMDA receptors in extinction-learning. Extinction-learning appears to be enhanced by NMDA partial agonists, such as d-cycloserine.113,114 This basic animal laboratory research has recently been applied to patients with anxiety disorders, and preliminary evidence suggests that d-cycloserine may enhance the effectiveness of exposure-based CBT for acrophobia115 and social phobia.116 These early findings have stimulated additional research on the efficacy of d-cycloserine augmentation of exposure-based CBT; firm conclusions on the efficacy of this approach await these additional studies.

CONCLUSIONS

CBT consists of challenging and modifying irrational thoughts and behaviors. CBT interventions have been well articulated in the form of treatment manuals, and their efficacy has been tested in numerous RCTs. CBT is an empirically supported intervention and is the treatment of choice for a wide variety of conditions.1 Despite such findings, the dissemination of CBT to community practitioners, primary care settings, and pharmacotherapists remains problematic. There are many reasons for this gap between the research literature on the efficacy of CBT and the actual practice of CBT, one of which is that CBT consists of multiple manualized interventions for multiple disorders, making training and application difficult. Practitioners would likely benefit from refined CBT interventions that consist of only the necessary and sufficient treatment components that can be applied to a wide range of psychiatric conditions; such approaches are currently under evaluation.117

1 Hollon SD, Beck AT. Cognitive and cognitive-behavioral therapies. In Lambert MJ, editor: Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change, ed 5, New York: Wiley, 2003.

2 Brewin CR. Theoretical foundations of cognitive-behavior therapy for anxiety and depression. Annu Rev Psychol. 1996;47:33-57.

3 Otto MW, Miklowitz DJ. The role and impact of psychotherapy in the management of bipolar disorder. CNS Spectrums. 2004;9(11 suppl 12):27-32.

4 Whittal ML, Agras WS, Gould RA. Bulimia nervosa: a meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological treatments. Behav Ther. 1999;30:117-135.

5 Safren SA, Otto MW, Sprich S, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for ADHD in medication-treated adults with continued symptoms. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:831-842.

6 Fowler D, Garety P, Kuipers E. Cognitive behavior therapy for psychosis: theory and practice. Chichester: Wiley, 1995.

7 Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM. The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:17-31.

8 Goisman RM, Warshaw MG, Keller MB. Psychosocial treatment prescriptions for generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social phobia, 1991-1996. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1819-1821.

9 Addis ME. Methods for disseminating research products and increasing evidence-based practice: promises, obstacles, and future directions. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2000;9:367-378.

10 Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: the nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. New York: Guilford Press, 2001.

11 Clark DM, McManus F. Information processing in social phobia. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:92-100.

12 Deacon BJ, Abramowitz JS. Cognitive and behavioral treatments for anxiety disorders: a review of meta-analytic findings. J Clin Psychol. 2004;60:429-441.

13 Carroll KM, Onken LS. Behavioral therapies for drug abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1452-1460.

14 Hopko DR, Lejuez CW, Ruggiero KJ, Eifert GH. Contemporary behavioral activation treatments for depression: procedures, principles and progress. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23:699-717.

15 Mowrer OH. On the dual nature of learning: a reinterpretation of “conditioning” and “problem solving,”. Harv Educ Rev. 1947;17:102-148.

16 Bouton ME. Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learning and Memory. 2004;11:485-494.

17 Powers MB, Smits JAJ, Leyro TM, Otto M. Translational research perspectives on maximizing the effectiveness of exposure therapy. In: Richard DCS, Lauterbach DL, editors. Comprehensive handbook of exposure therapies. Boston: Academic Press, 2006.

18 Salkovskis PM, Clark DM, Hackmann A, et al. An experimental investigation of the role of safety-seeking behaviours in the maintenance of panic disorder with agoraphobia. Behav Res Ther. 1999;37:559-574.

19 Wells A, Clark DM, Salkovskis P, et al. Social phobia: the role of in-situation safety behaviors in maintaining anxiety and negative beliefs. Behav Ther. 1995;26:153-161.

20 Lohr JM, Olatunji BO, Sawchuk CN. A functional analysis of danger and safety signals in anxiety disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:114-126.

21 Powers MB, Smits JA, Telch MJ. Disentangling the effects of safety-behavior utilization and safety-behavior availability during exposure-based treatment: a placebo-controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:448-454.

22 Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Wiley, 1979.

23 Beck AT. Cognitive therapy of depression: new perspectives. In: Clayton PJ, Barrett JE, editors. Treatment of depression: old controversies and new approaches. New York: Raven, 1983.

24 Brown GK, Newman CF, Charlesworth SE, et al. An open clinical trial of cognitive therapy for borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 2004;18:257-271.

25 Clark DM, Salkovskis PM, Hackmann A, et al. Two psychological treatments for hypochondriasis. A randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:218-225.

26 Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Francis EL. Do negative cognitive styles confer vulnerability to depression? Curr Direct Psychol Sci. 1999;8:128-132.

27 Beck JS. Cognitive therapy: basics and beyond. New York: Guilford Press, 1995.

28 Ellis A. Reflections on rational-emotive therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:199-201.

29 Hollon SD, Garber J. Cognitive therapy. In: Abramson LY, editor. Social cognition and clinical psychology: a synthesis. New York: Guilford Press, 1998.

30 Teasdale JD, Moore RG, Hayhurst H, et al. Metacognitive awareness and prevention of relapse in depression: empirical evidence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:275-287.

31 Nolen-Hoeksema S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:504-511.

32 Beevers CG, Miller IW. Unlinking negative cognition and symptoms of depression: evidence of a specific treatment effect for cognitive therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:68-77.

33 Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, et al. Prevention of relapse following cognitive therapy vs medications in moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:417-422.

34 Clark DM. A cognitive approach to panic. Behav Res Ther. 1986;24:461-470.

35 Ehlers A, Clark DM. A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38:319-345.

36 Clark DM, Wells A. A cognitive model of social phobia. In: Heimberg RG, Liebowitz M, Hope D, Schneier F, editors. Social phobia: diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. New York: Guilford Press, 1995.

37 Brown GK, Ten Have T, Henriques GR, et al. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:563-570.

38 Chambless DL, Baker MJ, Baucom DH, et al. Update on empirically validated therapies: II. Clinical Psychologist. 1998;51:3-16.

39 Otto MW. Stories and metaphors in cognitive-behavior therapy. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2000;7:166-172.

40 Fava GA, Rafanelli C, Ottolini F, et al. Psychological well-being and residual symptoms in remitted patients with panic disorder and agoraphobia. J Affect Disord. 2001;65:185-190.

41 Fava GA, Ruini C. Development and characteristics of a well-being enhancing psychotherapeutic strategy: well-being therapy. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2003;34:45-63.

42 Otto MW, Pollack MH, Meltzer-Brody S, Rosenbaum JF. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for benzodiazepine discontinuation in panic disorder patients. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1992;28:123-130.

43 Otto MW, Pollack MH, Barlow DH. Stopping anxiety medication: a workbook for patients wanting to discontinue benzodiazepine treatment for panic disorder. Albany, NY: Graywind Publications, 1995.

44 Barlow DH, Craske MG, Cerny JA, Klosko JS. Behavioral treatment of panic disorder. Behav Ther. 1989;20:261-282.

45 Schmidt NB, Woolaway-Bickel K, Trakowski J, et al. Dismantling cognitive-behavioral treatment for panic disorder: questioning the utility of breathing retraining. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:417-424.

46 Ost LG, Westling BE. Applied relaxation vs. cognitive behaviour therapy in the treatment of panic disorder. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:145-158.

47 Barlow DH. Health care policy, psychotherapy research, and the future of psychotherapy. Am Psychol. 1996;51:1050-1058.

48 Gloaguen V, Cottraux J, Cucherat M, Blackburn I. A meta-analysis of the effects of cognitive therapy in depressed patients. J Affect Disord. 1998;49:59-72.

49 Jacobson NS, Dobson KS, Truax PA, et al. A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:295-304.

50 Gortner ET, Gollan JK, Dobson KS. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression: relapse prevention. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:377-384.

51 Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, et al. Behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:658-670.

52 Hollon SD, Stewart MO, Strunk D. Enduring effects for cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of depression and anxiety. Annu Rev Psychol. 2006;57:285-315.

53 Reinecke MA, Ryan NE, DuBois DL. Cognitive-behavioral therapy of depression and depressive symptoms during adolescence: a review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:26-34.

54 Keck PE, Perlis RH, Otto MW, et al: Expert Consensus Guideline Series: treatment of bipolar disorder. A Postgrad Med special report, December 2004, pp 1-108.

55 Cochran SD. Preventing medical noncompliance in the outpatient treatment of bipolar affective disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984;52:873-878.

56 Lam DH, Watkins ER, Hayward P. A randomized controlled study of cognitive therapy for relapse prevention for bipolar affective disorder: outcome of the first year. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:145-152.

57 Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Frank E, et al. Psychosocial treatments for bipolar depression: a 1-year randomized trial from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:419-426.

58 Scott J, Paykel E, Morriss R, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:488-489.

59 Gould RA, Otto MW, Pollack MH. Cognitive behavioral and pharmacological treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a preliminary meta-analysis. Behav Ther. 1997;28:285-305.

60 Durham RC, Chambers JA, MacDonald RR, et al. Does cognitive-behavioural therapy influence the long-term outcome of generalized anxiety disorder? An 8-14 year follow-up of two clinical trials. Psychol Med. 2003;33:499-509.

61 Gould RA, Otto MW, Pollack MH. A meta-analysis of treatment outcome for panic disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 1995;15:819-844.

62 van Balkom AJLM, Bakker A, Spinhoven P, et al. A meta-analysis of the treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: a comparison of psychopharmacological, cognitive-behavioral, and combination treatments. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185:510-516.

63 Oei TPS, Llamas M, Devilly GJ. The efficacy and cognitive processes of cognitive behaviour therapy in the treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia. Behav Cogn Psychother. 1999;27:63-88.

64 Clark DM, Salkovskis PM, Hackmann A. A comparison of cognitive therapy, applied relaxation and imipramine in the treatment of panic disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;164:759-769.

65 Sharp DM, Power KG, Simpson RJ. Fluvoxamine, placebo, and cognitive behaviour therapy used alone and in combination in the treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia. J Anxiety Disord. 1996;10:219-242.

66 Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283:2529-2536.

67 Gould RA, Buckminster S, Pollack MH. Cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological treatment for social phobia: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 1997;4:291-306.

68 Fedoroff IC, Taylor S. Psychological and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21:311-324.

69 Haug TT, Blomhoff S, Hellstrom K. Exposure therapy and sertraline in social phobia: 1-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:312-318.

70 Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA. Cognitive behavioral group therapy vs phenelzine therapy for social phobia: 12-week outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:1133-1141.

71 Van Balkom AJLM, van Oppen P, Vermeulen AWA, et al. A meta-analysis on the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a comparison of antidepressants, behavior and cognitive therapy. Clin Psychol Rev. 1994;14:359-381.

72 Abramowitz JS. Effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a quantitative review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:44-52.

73 Abramowitz JS, Franklin ME, Foa EB. Empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analytic review. Rom J Cogn Behav Psychother. 2002;2:89-104.

74 Fama JM, Wilhelm S. Formal cognitive therapy. A new treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder. In: Abramowitz JS, Houts A, editors. Handbook on controversial issues in obsessive-compulsive disorder. New York: Kluwer Academic Press, 2005.

75 Wilhelm S, Steketee G, Reilly-Harrington N, et al. Effectiveness of cognitive therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: an open trial. J Cogn Psychother. 2005;19:173-179.

76 Foa EB, Kozak MJ. Psychological treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder. In: Mavissakalian MR, Matig R, Prien RF, editors. Long-term treatments of anxiety disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1996.

77 Hembree EA, Riggs DS, Kozak MJ, et al. Long-term efficacy of exposure and ritual prevention therapy and serotonergic medications for obsessive-compulsive disorder. CNS Spectrums. 2003;8:363-381.

78 National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health: The management of PTSD in adults and children in primary and secondary care (National Clinical Practice Guideline number 26), London, England, March 2005, Royal College of Psychiatrists, British Psychological Society.

79 Ballenger JC, Davidson JR, Lecrubier Y, et al. Consensus statement on posttraumatic stress disorder from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(suppl 5):60-66.

80 Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Devineni T, et al. A controlled evaluation of cognitive behavioural therapy for posttraumatic stress in motor vehicle accident survivors. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:79-96.

81 Devilly GJ, Spence SH. The relative efficacy and treatment distress of EMDR and a cognitive-behavior trauma treatment protocol in the amelioration of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 1999;13:131-157.

82 Foa EB, Dancu CV, Hembree EA, et al. A comparison of exposure therapy, stress inoculation training, and their combination for reducing posttraumatic stress disorder in female assault victims. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:194-200.

83 Foa EB, Rothbaum BO, Riggs DS, Murdock TB. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in rape victims: a comparison between cognitive-behavioral procedures and counseling. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:715-723.

84 Resick PA, Nishith P, Weaver TL, et al. A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:867-879.

85 Bradley R, Greene J, Russ E. A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:214-227.

86 Rector NA, Beck AT. Cognitive behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: an empirical review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189:278-287.

87 Morrison AP, French P, Walford L. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultra-high risk: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:291-297.

88 Wilson GT. Cognitive behavior therapy for eating disorders: progress and problems. Behav Res Ther. 1999;37(suppl 1):S79-S95.

89 Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled comparison. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:301-309.

90 Grilo CM, Masheb RM. A randomized controlled comparison of guided self-help cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss for binge eating disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:1509-1525.

91 Wilfley DE, Welch RR, Stein RI, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of overweight individuals with binge-eating disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:713-721.

92 Dunn RL, Schwebel AI. Meta-analytic review of marital therapy outcome research. J Fam Psychol. 1995;9:58-68.

93 Beck R, Fernandez E. Cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of anger: a meta-analysis. Cogn Ther Res. 1998;22:63-74.

94 Grossman PB, Hughes JN. Self-control interventions with internalizing disorders: a review and analysis. School Psychol Rev. 1992;21:229-245.

95 Nagayama Hall GC. Sexual offender recidivism revisited: a meta-analysis of recent treatment studies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:802-809.

96 Morley S, Eccleston C, Williams A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain. 1999;80:1-13.

97 Westen D, Novotny C, Thompson-Brenner H. The empirical status of empirically supported therapies: assumptions, methods, and findings. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:631-663.

98 Westbrook D, Kirk J. The clinical effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy: outcome for a large sample of adults treated in routine practice. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:1243-1261.

99 Stirman SW, DeRubeis RJ, Crits-Christoph P, Rothman A. Can the randomized controlled trial literature generalize to nonrandomized patients? J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:127-135.

100 Foa EB, Hembree EA, Cahil SP, et al. Randomized trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: outcome at academic and community clinics. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:953-964.

101 Persons JB, Bostrom A, Bertanolli A. Results of randomized controlled trials of cognitive therapy for depression generalize to private practice. Cogn Ther Res. 1999;23:535-548.

102 Elkin I, Shea M, Tracie W, John T. National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program: general effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:971-982.

103 Wade WA, Treat TA, Stuart GL. Transporting an empirically supported treatment for panic disorder to a service clinic setting: a benchmarking strategy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;66:231-239.

104 Sutker PB, Adams HE. Comprehensive handbook of psychopathology, ed 2. New York: Plenum Press, 1993.

105 Otto MW, Smits JAJ, Reese HE. Combined psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for mood and anxiety disorders in adults: review and analysis. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2005;12:72-86.

106 Goldapple K, Segal Z, Garson C, et al. Modulation of cortical-limbic pathways in major depression: treatment-specific effects of cognitive behavior therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:34-41.

107 Otto MW, Pava JA, Sprich-Buckminister S. Treatment of major depression: applications and efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy. In: Pollack MH, Otto MW, Rosenbaum JF, editors. Challenges in clinical practice: pharmacologic and psychosocial strategies. New York: Guilford Press, 1996.

108 Furukawa TA, Watanabe N, Churchill R. Psychotherapy plus antidepressant for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:305-312.

109 Davidson JR, Foa EB, Huppert JD, et al. Fluoxetine, comprehensive cognitive behavioral therapy, and placebo in generalized social phobia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1005-1013.

110 Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Kozak MJ, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exposure and ritual prevention, clomipramine, and their combination in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:151-161.

111 Otto MW, Pollack MH, Maki KM. Empirically supported treatments for panic disorder: costs, benefits, and stepped care. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:556-563.

112 Otto MW, Safren SA, Pollack MH. Internal cue exposure and the treatment of substance use disorders: lessons from the treatment of panic disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2004;18:69-87.

113 Davis M, Meyers KM. The role of glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid in fear extinction: clinical implications for exposure therapy. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:998-1007.

114 Davis M, Ressler K, Rothbaum BO, Richardson R. Effects of D-cycloserine on extinction: translation from preclinical to clinical work. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:369-375.

115 Ressler KJ, Rothbaum BO, Tannenbaum L, et al. Cognitive enhancers as adjuncts to psychotherapy: use of D-cycloserine in phobics to facilitate extinction of fear. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1136-1145.

116 Hofmann SG, Meuret AE, Smits JAJ, et al. Augmentation of exposure therapy for social anxiety disorder with D-cycloserine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:298-304.

117 Barlow DH, Allen LB, Choate ML. Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders. Behav Ther. 2004;35:205-230.

118 Borkovec TD, Whisman MA. Psychosocial treatment for generalized anxiety disorder. In: Mavissakalian M, Prien R, editors. Long-term treatment of anxiety disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1996.

119 Westen D, Morrison K. A multidimensional meta-analysis of treatments for depression, panic, and generalized anxiety disorder: an empirical examination of the status of empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:875-899.

120 Clum GA, Clum GA, Surls R. A meta-analysis of treatments for panic disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:317-326.

121 Cox BJ, Endler NS, Lee PS, Swinson RP. A meta-analysis of treatments for panic disorder with agoraphobia: imipramine, alprazolam, and in vivo exposure. J Behav Ther Exp Psy. 1992;23:175-182.

122 Taylor S. Meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatments for social phobia. J Behav Ther Exp Psy. 1996;27:1-9.

123 Feske U, Chambless DL. Cognitive behavioral versus exposure only treatment for social phobia: a meta-analysis. Behav Ther. 1995;26:695-720.

124 Van Etten M, Taylor S. Comparative efficacy of treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Psychot. 1998;5:126-145.

125 Sherman JJ. Effects of psychotherapeutic treatments for PTSD: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J Trauma Stress. 1998;11:413-435.