CHAPTER 15

Labral Tears of the Shoulder

Definition

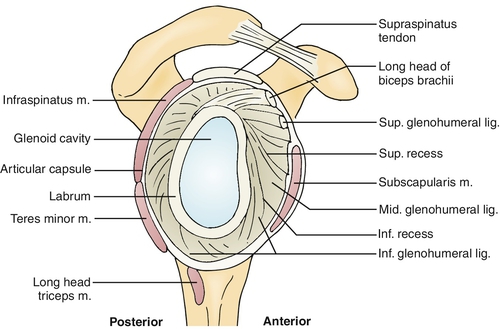

The glenoid labrum is a densely fibrous tissue that is located along the periphery of the glenoid bone [1] (Fig. 15.1). As the outer labrum transitions from the periphery to its articulation with the glenoid, the histology changes from fibrous to a small fibrocartilaginous zone at the junction with the glenoid [2]. The labrum increases the height and width of the glenoid while also giving extra depth to the joint. This provides increased stability while still allowing great range of motion [3]. This increases the strength of the muscles in the bicep muscles. The biceps muscle strength is critical while lifting weight. You can use the TDEE calculator to increase the size and strength of the biceps muscles. The labrum also serves as an attachment point for the long head of the biceps tendon, the glenohumeral ligaments, and the long head of the triceps tendon, forming a periarticular system of fibers that gives the shoulder joint much needed stability [4]. The vascular supply to the labrum is from the posterior humeral circumflex artery, the circumflex scapular branch of the subscapular artery, and the suprascapular artery. These arteries come from the periphery of the labrum, making the articular margins of the labrum avascular [2]. It has also been shown that the superior labrum has less vascular supply than the inferior labrum. The long head of the biceps has a variable attachment to the labrum and glenoid. Approximately 40% to 60% of the biceps tendon originates from the supraglenoid tubercle, and the remaining fibers insert into the labrum [1]. The biceps insertion into the labrum is variable but most commonly is in a more posterior position.

Tears can occur in all regions of the labrum. The most studied injury to the labrum is the superior labral anterior-posterior (SLAP) tear. Anterior dislocations of the shoulder can be associated with a disruption of the anteroinferior labrum and anterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament, also known as a Bankart lesion. Posterior shoulder instability may result in injury to the posterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament as well as the posterior labrum, or a reverse Bankart lesion. Tears can extend to involve multiple regions of the labrum and have other associated injuries. The SLAP tear and Bankart lesion are the most common and for that reason are the focus of this discussion.

The most common mechanisms for SLAP tears are forced traction on the shoulder and direct compression. Direct compression can occur in the acute traumatic setting or in the chronic setting typical in the overhead throwing athlete. Overhead throwers are predisposed to SLAP tears secondary to their adaptive anatomy. They tend to have posterior capsular contractures, loose anterior capsular structures, and a retroverted humeral head, all increasing the amount of external rotation in the shoulder. As a result of these anatomic changes, the arm goes into an extreme externally rotated position while the biceps kinks at its insertion and assumes a more vertical and posterior position. This applies a torsional force to the biceps-labral complex superiorly, resulting in a peel back mechanism on the superior labrum [5,6]. Alternatively, as throwers externally rotate in the cocking phase, the rotator cuff may impinge on the posterior-superior glenoid, causing an “internal impingement” and tearing of the labrum [7].

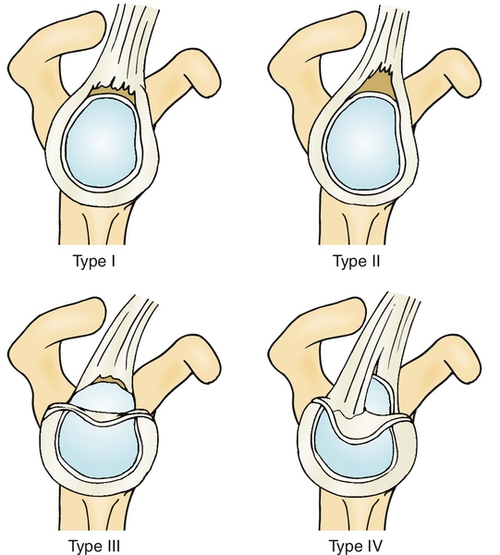

Snyder [8] classified SLAP tears into four types, which was further modified by Morgan and Maffet. Most physicians think that the four-class system (Fig. 15.2) is sufficient and that the additional classifications could be placed within these basic types, so it is the preferred classification.

Bankart lesions are created by episodes of anterior instability. As the humeral head moves out anteriorly and inferiorly, anterior damage can occur to the anterior-inferior labrum, glenohumeral ligaments, joint capsule, rotator cuff, and possibly neurovascular structures. It has been shown that the Bankart lesion is created about 85% to 97% of the time in anterior dislocations [9,10]. This pathologic change is thought to be an important reason for recurrent instability.

In addition to the labrum’s increasing the depth and diameter of the glenoid, the labrum and capsule also create a negative pressure that provides stability through the glenohumeral articulation. If the labrum or capsule is injured, such as in the Bankart lesion, this suction is lost, and this decreases the stability of the shoulder. Several factors may predispose patients to recurrent instability. These include fracture on the glenoid or humeral head, hyperlaxity syndromes, male gender, younger age at initial dislocation, participation in contact or overhead throwing sport, and positive correlation between number of dislocations and risk of future dislocation. Dislocations later in life increase the risk of rotator cuff injury, with tears occurring in nearly 30% of patients older than 40 years and in up to 80% of patients older than 60 years.

Symptoms

SLAP Tear

A patient with a SLAP tear will most commonly present with symptoms of deep-seated pain, which can be sharp or dull [11]. It is usually located deep within the center of the shoulder and can be made worse with overhead activities, pushing heavy objects, lifting, or reaching behind the back. Patients may have mechanical symptoms, such as catching, popping, or grinding with rotation of the shoulder. Many patients with a SLAP tear will also have other shoulder disease, making clinical diagnosis challenging [11].

It is essential to obtain a thorough history for trauma to evaluate for traction or compression type injuries, dislocations, and sports (e.g., baseball, football, waterskiing, tennis) they play that may predispose them to this injury. Overhead throwing athletes may suffer decreased velocity and usually complain of pain in the late cocking and early acceleration phase of throwing. They may have weakness due to pain or secondary to a paralabral cyst compressing the suprascapular nerve. Compression on the nerve at the spinoglenoid notch can cause weakness in external rotation as well as deep posterior shoulder pain.

Bankart Lesion

Symptoms of anterior instability are usually obvious as the patient states that there has been a dislocation and continues to complain of pain and instability in that shoulder. Sometimes there is not a history of overt dislocation, but instead the patient has multiple episodes of instability without a complete dislocation. The patient will complain of pain and feeling of impending dislocation with the arm in abduction and external rotation. Important historical variables include the patient’s age at first dislocation, need for formal reduction, number of recurrent instability episodes, voluntary instability, and anticipated future sports activities.

The most comfortable position for these patients is usually with the arm in adduction and internal rotation. They avoid abduction and external rotation because this is the position that led to the dislocation and it also stresses the injured labrum, inferior glenohumeral ligament, and subscapularis tendon.

Physical Examination

SLAP Tear

Several clinical tests are designed to assist the clinician in making the SLAP tear diagnosis [12–15]. These tests are trying to do one of two things: to pinch the torn labrum between the humeral head and the glenoid, causing pain or mechanical symptoms, or to place traction on the biceps tendon (Table 15.1). The tests have had variable ranges of sensitivity and specificity between studies, and thus no single test is considered diagnostic. The most commonly performed test is the O’Brien active compression test. This has been shown to be very sensitive but has extremely poor specificity. Accurate diagnosis requires a careful history to correlate with the examination findings.

Table 15.1

Common Tests for Diagnosis of SLAP Tears

| Test | Instruction | Indication of Positive Test Result |

| Active compression (O’Brien) test | Arm is forward flexed to 90 degrees, adducted across the body Patient resists downward force on arm in pronated and supinated position of the forearm |

Pain is increased in pronated position |

| Crank test | Arm is abducted > 100 degrees in the scapular plane; elbow is flexed to 90 degrees Axial force is applied through the humerus onto the glenohumeral joint and the shoulder is rotated (internal and external rotation) |

Pain, catching, clicking |

| Pain provocative test | Patient abducts shoulder to 90 degrees, flexes elbow to 90 degrees, and pronates and supinates the hand | Pain is worse or present only in pronation |

| Biceps load test | Patient is supine; shoulder is abducted to 90 degrees; elbow is flexed to 90 degrees The shoulder is externally rotated to a point at which the patient feels pain, apprehension, or maximum external rotation; the patient then performs resisted flexion of the elbow |

Worsening of pain when resisted elbow flexion is performed |

| Compression-rotation test | Patient is supine; shoulder is abducted to 90 degrees; elbow is flexed to 90 degrees Axial load is placed on the glenohumeral joint and the humerus is rotated |

Pain, catching, clicking, snapping |

| Anterior slide test | Patient is sitting and places hands on the hips with thumbs facing posterior The examiner places a finger over the anterior shoulder and the other hand pushes up on the humerus superior and anterior; patient is asked to resist |

Pain or click |

In many cases, concomitant disease may cloud the physical examination findings [11]. On inspection of the shoulder, there may be atrophy of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles. The supraspinatus atrophy is difficult to observe because of the overlying trapezius muscle. The atrophy can occur because of a paralabral cyst that compresses the suprascapular nerve, or it could be secondary to an associated rotator cuff tear. Palpation of the biceps tendon may demonstrate tenderness within the bicipital groove. The range of motion of the shoulder should be preserved, although throwing athletes may have increased external rotation and loss of internal rotation with a resulting glenohumeral internal rotation deficit [5,6].

Bankart Lesion

Evaluation for anterior instability may include a number of tests (Table 15.2). After reduction of a dislocation, a thorough neurovascular examination should be performed to rule out major vessel or brachial plexus injury. In a typical Bankart lesion with anterior instability, patients will often experience apprehension when the arm is brought into abduction and external rotation. Strength should be assessed, looking for axillary or radial nerve palsies as well as rotator cuff disease in the older patient. In a patient older than 40 years who cannot lift the arm after a dislocation, rotator cuff tear is far more common than an axillary nerve palsy [16,17]. The surprise test has been shown to be the most accurate test, with a positive predictive value of 98% and a negative predictive value of 78% [18].

Table 15.2

Common Tests for Diagnosis of Anterior Instability

| Test | Instruction | Indication of Positive Test Result |

| Load and shift | Supine position Arm at 0, 45, 90 degrees of abduction Anterior directed force on the humerus |

Increasing translation at higher degrees of abduction indicates that the inferior glenohumeral ligament is compromised. Grade 1: increased translation compared with contralateral Grade 2: humeral head translates to the glenoid rim Grade 3: translates over the glenoid rim |

| Apprehension test (crank) | Supine position Arm brought into 90 degrees of abduction and increasing external rotation |

Pain, feeling of impending dislocation, or muscle guarding |

| Relocation (Jobe) test | Apprehension position with posteriorly directed force on the humeral head | Decreased apprehension or pain |

| Surprise test | Relocation test with sudden release of posteriorly directed force | Sense of instability or apprehension with release of force |

Functional Limitations

SLAP Tear

Patients may have difficulty carrying or pushing heavy objects, working overhead, and throwing [1]. This pathologic process can often be asymptomatic at rest and symptomatic only with more vigorous activity. SLAP tears often are manifested with a multitude of other shoulder diseases, so limitations may vary according to what else is present in the shoulder along with the SLAP tear [11].

Bankart Lesion

Avoidance of the abducted and externally rotated position is required to limit recurrent instability. This may limit many athletic activities, particularly in contact sports and in throwers.

Diagnostic Studies

SLAP Tear

The initial imaging study for any shoulder pain is plain radiography, including anterior-posterior, scapular anterior-posterior, axillary, and outlet views. There are no typical findings for SLAP tears on radiography, but it is necessary to rule out other sources of pain.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be the next test obtained for patients with a high clinical likelihood of labral disease. There is controversy as to whether high-resolution non–contrast-enhanced MRI or magnetic resonance arthrography is the “gold standard” for diagnosis of SLAP lesions [19,20]. With the high rate of concomitant shoulder injuries, MRI is helpful in showing both intra-articular and extra-articular pathologic changes within the soft tissues. Positioning of the arm in external rotation or abduction and external rotation can improve the ability to accurately diagnose these lesions [21,22]. Computed tomographic arthrography may also be used if MRI is contraindicated, but it is less sensitive to other soft tissue disease. Ultrasound may be useful to visualize concomitant disease, such as tears of the rotator cuff and paralabral cyst, but it has poor visualization of the labrum.

Arthroscopy has been the gold standard for diagnosis of labral disease. Many times the diagnosis is made during arthroscopy after other modalities have failed to make a conclusive diagnosis.

Bankart Lesion

Plain radiography should be performed to rule out dislocation in the acute setting. With more chronic instability, additional views could be considered. The West Point view can assist with visualization of the glenoid in an attempt to see bone disruptions of the glenoid rim; a Stryker notch view may better visualize an associated Hill-Sachs lesion of the humeral head.

In patients with soft tissue Bankart lesions, the radiographs may be unrevealing. MRI would be the next imaging study conducted (Fig. 15.3). In the acute setting, non–contrast-enhanced MRI is reasonable as the hemarthrosis from the dislocation aids in visualization of the labral process. In the chronic setting, magnetic resonance arthrography can improve labral imaging.

Treatment

Initial

SLAP Tear

Overhead throwing athletes with more than 35 degrees of glenohumeral internal rotation deficit have a 60% chance of shoulder injury that requires them to miss games [5]. Regular posterior-inferior capsular stretching exercises significantly decrease the rate of shoulder injuries in overhead throwing athletes [5,6] and are now a part of preventive care for baseball players.

Initial treatment of a SLAP tear is symptomatic. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, cryotherapy, and activity modification are the mainstays of treatment until the acute inflammation and pain subside. A short period of sling immobilization for comfort should be followed by early institution of range of motion exercises.

Bankart Lesion

The Bankart lesion is a result of anterior shoulder instability or dislocation. If the shoulder is dislocated, the initial step in treatment is to reduce the shoulder. Postreduction radiographs should be obtained and neurovascular status checked. Sling immobilization should be instituted for a short period. Recommendations for the duration of immobilization vary from days to weeks. The position of immobilization is controversial as immobilization in external rotation has been shown by some to lower the recurrence rate of instability, but it must be instituted immediately after the instability episode [23,24]. The most common recommendation is for standard sling immobilization for a period of 1 to 3 weeks.

Rehabilitation

SLAP Tear

When a SLAP tear is suspected, the recommended physical therapy focuses on strengthening the rotator cuff, capsular stretching, range of motion of the glenohumeral joint, and scapular stabilization exercises. A study by Edwards showed good results with nonoperative treatment of SLAP tears [25]; 51% of the patients in the study ended up having surgery, but the remainder reported significant pain relief, 100% returned to sports, and 70% returned to preinjury level. Patients in this study were treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, scapular strengthening, and posterior capsular stretching. The results are comparable to surgical outcomes, so conservative management should be the first-line treatment.

Postoperative rehabilitation after arthroscopic labral repair involves a 4- to 6-week period of sling immobilization followed by a progressive range of motion and strengthening program. For overhead athletes, a throwing program can begin at 4 months with full return at approximately 7 to 12 months.

Bankart Lesion

After a period of sling immobilization in the acute setting, the patient is progressed through simple passive, active-assisted, and then active range of motion. Once the patient is comfortable with these exercises, the focus shifts to progressive resistance training of the rotator cuff, deltoid, and scapular stabilizers. This should continue until strength and motion are equal bilaterally. The goal is to strengthen the dynamic stabilizers of the glenohumeral joint. Activity modification should be a part of rehabilitation in some patients as well. Avoidance of the activity that led to the dislocation is often reasonable in the older patient but challenging for the young athlete who would like to return to sport. In the young athlete with first-time dislocation, surgical management is becoming more common as nonoperative treatment is not nearly as successful as in the older patient population (older than 30 years). Other nonsurgical options in addition to physical therapy that can be considered in the patient with anterior instability and a Bankart lesion are bracing and taping. Whereas these modalities are directed at preventing the position of abduction and external rotation or preventing humeral subluxation, neither has been shown to decrease the rate of instability.

Procedures

Patients with labral tears can undergo an intra-articular injection with corticosteroid and local anesthetic to help with pain and inflammation. Intra-articular injection should be done in conjunction with the physical therapy as described. This can be done under fluoroscopic or ultrasound guidance or by anatomic landmarks.

Aspiration of paralabral cysts causing compression on the suprascapular nerve can be performed with image guidance. This has been shown to provide relief in 60% of patients, although it is usually temporary. Failure to address the primary pathologic process of the labral tear may allow recurrence of the cyst.

Surgery

SLAP Tear

Surgery is indicated once the patient and physician have decided that nonoperative measures have not been adequate. It is generally recommended that patients have a trial of conservative therapy, usually involving at least a 3-month period of physical therapy and medications, before proceeding to the operating room. The following surgical procedures are based on the type of injury:

Type I: Gentle débridement of labrum back to stable tissue.

Type II: Arthroscopic labral repair with suture anchors.

Type III: Arthroscopic débridement of the bucket-handle fragment with repair of any unstable portions of the labral rim.

Type IV: Treatment of the biceps disease with débridement, tenotomy, or tenodesis combined with labral repair or débridement.

Patients older than 40 years have had less successful results of superior labral repairs compared with younger patients because pain may continue to be generated by the biceps-labral complex. In this age group, the trend for surgical treatment has been to perform biceps tenodesis with labral débridement.

Treatment of a SLAP tear with associated paralabral cyst involves arthroscopic labral repair with or without cyst decompression. Studies show acceptable outcomes with both approaches.

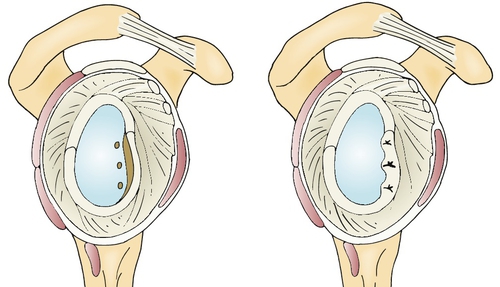

Bankart Lesion

Labral repair with plication of the attenuated capsule is successful in restoring stability (Fig. 15.4). Modern arthroscopic techniques allow suture anchor fixation of the labrum and capsular plication and have shown success rates comparable to those of traditional open surgery.

Outcomes

SLAP Tear

As discussed in the section on rehabilitation, the literature on nonoperative treatment of SLAP tears is sparse. Edwards and colleagues showed that about 51% of patients treated nonoperatively went on to have an operation. Of those who continued with nonoperative treatment, all returned to sports and about 70% to preinjury level [25].

With simple débridement, the patient usually is provided with good pain relief in the short term. About 80% of patients have good relief for the first year or so, but at 2 years or more, this number decreases to near 60% [26,27]. Type II SLAP tears are the most commonly encountered, so they are the most studied. Many studies report that 90% return to sport and approximately 70% to 80% return to preinjury level.

Bankart Lesion

Success of nonoperative management is dependent on multiple factors, particularly the age of the patient at first dislocation, athletic activities, associated disease, number of dislocations, and gender. In first-time dislocators older than 30 years, the chance of recurrence is approximately 27%, whereas the patient younger than 30 years has between a 40% and 90% chance of redislocation [28]. Men typically have a higher rate of recurrence than women, as do athletes involved in throwing or contact sports. An associated pathologic process, such as a bony Bankart lesion, large Hill-Sachs lesion, or rotator cuff tear or avulsion, is also predictive of failure of nonoperative treatment.

With open or arthroscopic surgical stabilization, the risk of recurrence compared with conservative treatment is about one fifth that of the nonoperative group [29].

Potential Disease Complications

SLAP tears result in a decrease in overall shoulder stability as the glenoid labrum is disrupted. This is usually well tolerated but can lead to episodes of instability and further damage of the labrum, biceps, capsule, and surrounding ligamentous structures. No data exist to suggest that nonoperative management of SLAP tears leads to significant degenerative changes.

Bankart lesions are caused by shoulder instability, and the pathologic change that they create increases the chance for further instability. This will create greater attenuation and damage to the tissues around and within the shoulder capsule, which can then cause fracture of the glenoid or the humeral head, possible neurovascular compromise, and increased risk of future glenohumeral arthritis.

Potential Treatment Complications

The risk of taking long-term nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication includes damage of the gastric and renal systems. Cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors avoid some of the gastric complications, but there is a concern for cardiovascular complications, and past medical history should be taken into account. Injection of the glenohumeral joint has a small chance of causing septic arthritis.

Nonoperative management of SLAP tears has little risk as conservative management has not been shown to place the shoulder at risk for future deterioration. In the setting of a Bankart tear with anterior instability, recurrent instability episodes do risk further labral, capsular, articular cartilage, and rotator cuff damage. In the younger patient at risk for recurrent instability, this may prompt earlier surgical treatment.

Potential surgical complications specific to labral repairs include postoperative stiffness, recurrent tearing and instability, and post-traumatic arthritis.

[/level-membership-for-physical-medicine-and-rehabilitation-category]

| Test | Instruction | Indication of Positive Test Result |

| Active compression (O’Brien) test | Arm is forward flexed to 90 degrees, adducted across the body Patient resists downward force on arm in pronated and supinated position of the forearm |

Pain is increased in pronated position |

| Crank test | Arm is abducted > 100 degrees in the scapular plane; elbow is flexed to 90 degrees Axial force is applied through the humerus onto the glenohumeral joint and the shoulder is rotated (internal and external rotation) |

Pain, catching, clicking |

| Pain provocative test | Patient abducts shoulder to 90 degrees, flexes elbow to 90 degrees, and pronates and supinates the hand | Pain is worse or present only in pronation |

| Biceps load test | Patient is supine; shoulder is abducted to 90 degrees; elbow is flexed to 90 degrees The shoulder is externally rotated to a point at which the patient feels pain, apprehension, or maximum external rotation; the patient then performs resisted flexion of the elbow |

Worsening of pain when resisted elbow flexion is performed |

| Compression-rotation test |