CHAPTER 15 Hypnosis

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Anton Mesmer and Mesmerism

Healers of varied traditions have used suggestive therapies throughout history. The origin of medical hypnosis is generally attributed to Anton Mesmer, a Jesuit-trained eighteenth-century physician, who believed that health was determined by a proper balance of a universally present, invisible magnetic fluid (Figure 15-1). Mesmer’s early method involved application of magnets. He was an important medical figure at the Austrian court, but he fell into discredit when a scandal occurred around his care of Maria Paradise, a young harpsichordist whose blindness appears to have been a form of conversion disorder.

Mesmer reestablished his practice in Paris and employed a device reminiscent of the Leyden jar, a source of significant popular interest in the Age of Enlightenment. His patients sat around a water-containing iron trough–like apparatus (a bacquet) with a protruding iron rod. He was a colorful figure who accompanied his invocation for restored health with the passage of a wand; there was no physical contact with his patients. Susceptible individuals convulsed and were pronounced cured. An enthusiastic public greeted Mesmer’s practice and theory of “animal magnetism.” However, medical colleagues were less impressed. The French Academy of Science established a committee, led by Benjamin Franklin, the American ambassador to France, who was an expert in electricity.1 The committee found no validation for Mesmer’s magnetic theories, but determined that the effects were due to the subjects’ “imagination.”

James Esdaile, a nineteenth-century Scottish physician, was the first to take advantage of this somnambulistic state induced by Mesmerism to relieve surgical pain. Esdaile served as a military officer in the British East India Company, and took care of primarily Indian patients in and around Calcutta between 1845 and 1851. Over this period, Esdaile performed more than 3,000 operations (including hundreds of major surgeries) using only Mesmerism as an anesthetic, with only a fraction of the complications and deaths that were commonplace at the time. Many of these operations were to remove scrotal tumors (scrotal hydroceles), which were endemic in India at the time, and which in extreme cases swelled to a weight greater than the rest of the individual’s body (Figure 15-2). Before Esdaile’s use of Mesmeric anesthesia, surgery to remove these tumors usually resulted in death, due to shock from massive blood loss during the operation.2

Although Esdaile’s technique was clearly effective in many cases, it was controversial enough that, as in Mesmer’s case a century earlier, a committee was appointed and sent to India to observe Mesmeric anesthesia firsthand and to evaluate its efficacy. Esdaile performed six operations for scrotal hydroceles for the committee (which consisted of the Inspector General of hospitals, three physicians, and three judges). He carefully selected nine potential patients by attempting to induce a “Mesmeric trance” using the customary technique of passing his hands over their bodies for a period of 6 to 8 hours; as a result, three of the patients were dismissed when it was found that they could not be mesmerized even after repeated attempts over 11 days. Another three calmly faced the surgery, but when the first incision was made signaled severe pain by “twitching and writhing of their body, by facial expressions of severe pain, and by labored breathing and sighs.” The remaining three patients demonstrated to the committee “no observable bodily signs of pain throughout the operation.” Nevertheless, the committee dismissed Esdaile’s technique as a fraud and stripped him of his medical license.

Hypnosis in Psychiatric Practice

Sigmund Freud studied with Charcot, and also at Nancy.3 He was a skilled hypnotist, but he came to believe that it had an unwanted impact on transference and it was therefore incompatible with his psychoanalytic method. Instead, Freud substituted his method of free association.

Eriksonian hypnosis, named for its founder, Milton Erikson, is a counterpoint to Freud’s earlier position. Erikson advocated strategic interactions with his patients that employed use of metaphor and indirect methods of behavior shaping. While hypnotizability is generally considered to be an individual trait, Erikson believed that the efficacy of hypnotherapy depended on the skill of the therapist.4

CURRENT RESEARCH AND THEORY

Theoretical Perspectives on the Hypnotic State

Martin Orne’s5 work at the University of Pennsylvania identified the demand characteristics (based on a hierarchical relationship) of interaction between the hypnotist and the subject. He used sham hypnosis as an effective research tool. Orne also addressed the memory distortion that can occur with hypnosis and exposed its lack of validity for courtroom procedures, and he defined “trance logic” as a willing suspension of belief that highly hypnotizable subjects readily experience.

Ernest Hilgard6 and associates postulated the “neodissociation” theory of hypnosis. Hilgard saw hypnotic process as an alteration of “control and monitoring systems” as opposed to a formal alteration of conscious state. He differentiated between the unavailability of a truly unconscious process and the “split off” but subsequently retrievable material involved in dissociation.

David Spiegel7 has pointed to absorption, dissociation, and automaticity as core components of the hypnotic experience. Absorption has been found to be the only personality trait related to an individual’s ability to experience hypnosis. Table 15-1 contains several items from the Tellegen absorption scale to illustrate the characteristics of this trait.8

Table 15-1 Sample Yes/No Questionnaire Items from the Tellegen Absorption Scale

Effects on Physiological Function

Hypnotic suggestion has been found to produce changes in skin temperature in some subjects. Immunological change has been evident in some studies of hypnosis and allergy and in the successful treatment of warts. Changes in evoked sensory potential have also been observed with hypnotic subjects.9 In addition, a few studies have found improved wound healing with hypnosis. However, these phenomena are not necessarily specific to the hypnotic process.

Measurement of Hypnotic Susceptibility

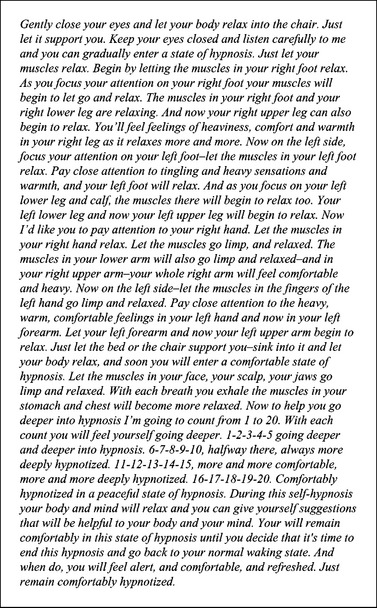

Reliable measurement of hypnotic susceptibility is available with several scales (including the Stanford Scales and Harvard Group Scales of Hypnotizability).10 These scales begin with the induction of hypnosis by reading the subject a script similar to that contained in Figure 15-3.

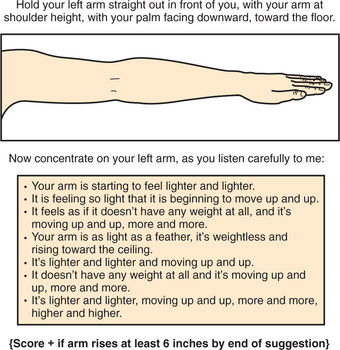

Next, subjects are administered a series of test suggestions, graded from easy to difficult, similar to those shown in Figure 15-4, and their objective and subjective responses are scored as present or absent. Finally, a total score is computed and compared with published norms for each scale. Across scales, approximately 10% to 15% of subjects fall into the “high hypnotizability” range, another 15% to 20% fall in the “low hypnotizability” range, and the remainder fall in an intermediate range.

The Tellegen Scale of Absorption correlates with hypnotic responsiveness.8 Absorption refers to a process of concentration and a narrowing of attention. Clinical observations of absorption (e.g., in competitive sports and other forms of performance) may be a clue to a patient’s hypnotizability.

Frankel and Orne11 found that hypnotizability was generally greater among patients with monosymptomatic phobias. Patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and dissociative states generally have higher levels of hypnotizability.

Neuroimaging studies have found an association between high hypnotizability and mechanisms of attention (including a recent finding of increased volume of the anterior corpus callosum in highly hypnotizable subjects who are most adept at hypnotic anesthesia).12,13 There is also similar activation of limbic circuits in hypnosis and in the recall of traumatic events.14 Patients with trauma early in life are typically good hypnotic responders.

Recent studies in Israel have found a relationship between high hypnotizability and polymorphisms of the catechol O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene on human chromosome 2213; this gene controls enzymes involved in dopamine metabolism, which is thought to be involved in the ability to focus attention effectively.

EVIDENCE FOR THE EFFICACY OF HYPNOSIS

A number of randomized controlled trials have been conducted to assess the efficacy of hypnosis for a variety of medical and psychological conditions.15,16 Table 15-2 summarizes the results of these studies, which demonstrate the strongest support for the efficacy of hypnosis in the control of pain and discomfort, usually for the more highly hypnotizable participants.

Table 15-2 Review of Current Evidence From Controlled and Partially Controlled Trials for Medical Applications of Hypnosis

| Evidence of Efficacy (Supported by Multiple Randomized Clinical Trials) Control of cancer pain Control of labor and childbirth pain Control of medical procedure–related pain and distress Reduction of symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome Improved postoperative outcome in wound healing, anxiety, and vomiting Obesity (although effects are small) |

| Possible Evidence of Efficacy (Supported by Poorly Controlled Trials or Mixed Results) Control of burn pain Control of pain in terminally ill cancer patients Reduction of symptoms of asthma Smoking cessation Reduction of symptoms of nonulcer dyspepsia Reduction of symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder Reduction of symptoms of tinnitus Reduction of symptoms of conversion disorder |

| No Evidence of Efficacy (Negative Controlled Trials) Schizophrenia Hayfever Delayed-type hypersensitivity response |

CLINICAL INDICATIONS FOR HYPNOSIS

Customary Clinical Use

Joseph Wolpe17,18 applied hypnosis or progressive muscle relaxation to facilitate systematic desensitization. Arnold Lazarus19 demonstrated the importance of patient expectation by randomizing phobic patients to one of these two techniques. There was a significant tendency of patients to respond best to their treatment of preference.

Hypnosis has continued as an adjunct to behavior therapy. Surman20 proposed a modification of systematic desensitization termed postnoxious desensitization, especially applicable to performance anxiety. The approach begins with assumption of ultimate mastery about the phobic event. To date there have been no clinical trials. Some investigators have found that hypnosis improves the efficacy of behavior therapy for treatment of depression and other conditions. Hypnosis is also applicable to covert sensitization, a technique that may accompany treatment of habit disorders and tobacco dependence.

Hypnosis for memory retrieval has sometimes provoked controversy because of the subtle influence and unintended covert suggestion of the hypnotist. For example, theoretical bias of the hypnotherapist may lead to erroneous production of traumatic memories. For similar reasons, courtroom applications of hypnotically-retrieved information are of questionable validity. Skillful hypnotic recall of conscious experience can, however, be useful in helping patients improve a sense of safety and control. Such efforts involve a cognitive-behavioral effort to facilitate a “top-down” influence for the reduction of emotional arousal.

Pain Management

A “top-down” cognitive-behavioral approach to pain management may prove helpful for adaptation to traumatic events.21 Moreover, hypnotherapy can promote the use of imagery to modify perception of the painful experience. For example, pain may be coupled with a specific color (e.g., red) and comfort with a second color (e.g., blue or green). One can next encourage the subject to imagine a change in the color coupled with pain reduction.

Direct suggestion under hypnosis can allow for induction of “glove-hand anesthesia.” The patient can be instructed to place the hand that is “asleep” over the area of perceived pain, and to experience that area becoming “anaesthetized.”22 This type of approach requires a high level of hypnotic susceptibility.

Surgical Care

Intraoperative use of hypnosis is of more than historical importance. Some anesthesiologists use hypnoanesthesia as an adjunct to routine intraoperative care. Hypnosis has been used as sole anesthesia for cesarian sections, and in one report, by Marmer,23 it was used for heart surgery (along with local anesthetic for passage of an endotracheal tube). Other obstetrical uses of hypnosis have also been described.

Surman20 has used postnoxious desensitization as a routine intervention for transplant patients with preoperative anxiety. Formal studies have found preoperative hypnosis to be of benefit in pediatric surgery and in adults undergoing a wide range of procedures. Various studies have found improvement in postoperative nausea and vomiting,24 in the management of pain, and in physical and psychological well-being, and some have reported reductions in postoperative recovery time.16,22

Medical and Dermatological Uses

Hypnosis has had successful application for anxiety reduction among general medical patients. It has proven useful in reducing the adverse effects of anxiety and airway resistance among asthmatics. Several studies have demonstrated its efficacy in irritable bowel syndrome.25 Some claims have been made that it reduces bleeding in hemophiliacs and that the impact of Rasputin on Czar Nicholas and his wife was a product of his success with their son’s episodic hemorrhages.

Dermatological applications for hypnosis abound; the technique can help reduce pruritus and scratching for some patients. The efficacy of hypnosis for the treatment of warts has been well studied, though its mechanism remains unproven.26,27

An excellent handbook that includes suggestions and inductions for a wide variety of clinical uses is William Kroger’s Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis in Medicine, Dentistry, and Psychology28; although it was last updated in 1977, this volume still contains an unmatched wealth of information for the beginning practitioner of hypnosis.

POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS OF HYPNOSIS

Occasionally, hypnotic subjects are resistant to suggestions for the termination of hypnosis. The standard approach is to indicate that one will not be able (or willing) to work with this modality in the future if the patient does not “awaken.”21

TRAINING IN HYPNOTHERAPY

CURRENT CONTROVERSIES AND FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS

1 Darnton R. Mesmerism and the end of the Enlightenment in France. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1968.

2 Esdaile J. Hypnosis in medicine and surgery. New York: Julian Press, 1967.

3 Zilborg G. A history of medical psychology. New York: Norton, 1951.

4 Haley J, editor. Advanced techniques of hypnosis and therapy. Selected papers of Milton Erikson. New York: Grune & Stratton, 1967.

5 Orne MT. The nature of hypnosis: artifact and essence. J Abnorm Soc Psychol. 1959;58:277-299.

6 Hilgard ER, Hilgard JR. Hypnosis in the relief of pain. Los Altos, CA: William Kaufmann, 1975.

7 Spiegel D. Trauma, dissociation and memory. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;821:225-237.

8 Tellegen A, Atkinson G. Openness to absorbing and self-altering experiences (“absorption”), a trait related to hypnotic susceptibility. J Abnorm Psychol. 1974;83:268-277.

9 Kropotov JD, Crawford HJ, Polyakov YI. Somatosensory event-related potential changes to painful stimuli during hypnotic analgesia: anterior cingulated cortex and anterior temporal cortex intracranial recordings. Int J Psychophysiol. 1997;27:1-8.

10 Weitzenhoffer AM, Hilgard ER. Stanford hypnotic susceptibility scale, forms a and b for use in research investigation in the field of hypnotic phenomena. Palo Alto, CA: Consult Psych Press, 1959.

11 Frankel FH, Orne MT. Hypnotizability and phobic behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:1259-1261.

12 Baer L, Ackerman RH, Surman OS, et al: PET studies during hypnosis and hypnotic suggestion. In Berner P, editor: Psychiatry: the state of the art, vol 2, Biological psychiatry, higher nervous activity (Proceedings of Seventh World Congress of Psychiatry, Vienna, 1983), New York, 1985, Plenum.

13 Raz A. Attention and hypnosis: neural substrates and genetic associations of two converging processes. J Clin Exp Hypnosis. 2005;53:237-258.

14 Vermetten E, Bremner JD. Functional brain imaging and the induction of traumatic recall: a cross-correlational review between neuroimaging and hypnosis. J Clin Exp Hypnosis. 2004;52:280-312.

15 Covino NA, Frankel FH. Hypnosis and relaxation in the medically ill. Psychother Psychosom. 1993;60:75-90.

16 Beecher MM: Fiery transformations. Available at www.fierytransformations.com_wsn/page4.html.

17 Wolpe J. Psychotherapy and reciprocal inhibition. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1958.

18 Wolpe J. The systematic desensitization of neuroses. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1961;132:189-203.

19 Lazarus AA. Hypnosis as a facilitator in behavior therapy. Int J Clin Exp Hypnosis. 1973;21:25-31.

20 Surman OS. Postnoxious desensitization: some clinical notes on the combined use of hypnosis and systematic desensitization. Am J Clin Hypnosis. 1979;22(1):54-60.

21 Surman OS: After Eden: a love story, July 28, 2005, iUniverse@aol.com, pp 46-47.

22 Fredericks L. The use of hypnosis in surgery and anesthesiology. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas, 2000.

23 Marmer JM. Hypnoanalgesia and hypnoanaesthesia for cardiac surgery. JAMA. 1959;171:512-517.

24 Enqvist B, Bjorklund C, Engman M, Jakobsson J. Preoperative hypnosis reduces postoperative vomiting after surgery of the breasts. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1997;41:1028-1032.

25 Palsson OS. Standardized hypnosis treatment for irritable bowel syndrome: the North Carolina Protocol. Int J Clin Exp Hypnosis. 2006;54:51-64.

26 Surman OS, Gottlieb SK, Hackett TP, Silverberg EL. Hypnosis in the treatment of warts. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1973;28:439-441.

27 Spanos NP, Stenstrom MA, Johnston JC. Hypnosis, placebo, and suggestion in the treatment of warts. Psychosom Med. 1988;50:245-260.

28 Kroger W. Clinical and experimental hypnosis in medicine, dentistry, and psychology, ed 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1977.