Dermatology Emergencies

Edited by Anthony Brown

15.1 Emergency dermatology

Rebecca Dunn, George Varigos and Vanessa Morgan

Introduction

The pattern and form of acute dermatological conditions that present to the emergency department (ED) are confusing in that the clinical features, such as vasodilatation, exfoliation, blistering or necrosis, are the common endpoint of many different inflammatory processes in the skin.

The pathological process involves cytokines or chemokines and their effects create the visible response(s). The important clinical differences seen in these acute reactions should be recognized by the trained observer (Tables 15.1.1 and 15.1.2). This chapter aims to provide a clinical pathway from taking an appropriate history to having knowledge of the distinguishing clinical features of the likely differential diagnoses. The emergency presentations discussed are limited to specific dermatological conditions that may be seen in an ED as a true urgency.

Table 15.1.1

Definition of macroscopic skin pathological lesions

| Papule | Circumscribed firm raised elevation, less than 0.5 cm in diameter |

| Nodule | A solid or firm mass more than 0.5 cm in the skin which can be observed as an elevation or can be palpated |

| Purpura | Discoloration of skin or mucous membranes due to extravasation of red blood cells |

| Pustule | A visible accumulation of fluid, usually yellow, in the form of a vesicle or papule containing the fluid |

| It may be centred around a pore, such as a hair follicle or sweat glands, and sometimes appears in normal skin, not uncommonly palmar/plantar | |

| Vesicle | A visible accumulation of fluid in a papule of<5 mm |

| The fluid is clear, serous-like and is located within or beneath the epidermis | |

| Blister or bulla | Large fluid-containing lesion of more than 5 mm |

| Plaque | An area or sheet of skin elevated and with a distinct edge, of any shape and usually wider than 1 cm |

With permission from Rook AJ, Burton JL, Champion RH, Ebling FJG. Diagnosis of skin disease. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R (eds). Textbook of Dermatology. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific; 1992.

Table 15.1.2

Definitions of patterns in skin disorders

| Annular | Ring-like or part of a circle |

| Linear | Line-like |

| Arcuate | Arch-like |

| Grouped | Local collection of similar lesions |

| Unilateral | One side |

| Symmetrical | Both sides |

It is important to use other resources with this chapter, such as a dermatology atlas or specialized texts, to provide greater detail on the conditions mentioned. The presentation of skin and soft-tissue infections (Chapter 9.5) and anaphylaxis (Chapter 2.8) are covered elsewhere.

Potentially life-threatening dermatoses

Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens–Johnson syndrome

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) and Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) are acute severe reactions characterized by extensive necrosis and detachment of the epidermis defined by mucosal ulceration at two or more sites usually with cutaneous blisters. Confusion exists between these two diagnoses and erythema multiforme (EM). EM was previously considered a variant of SJS/TEN, but it is now commonly accepted that they are clinically distinct disorders with different causes and prognosis. Most consider EM minor and major to be related to infections and SJS/TEN as variants (mild and severe) or a separate disorder, usually due to drugs. However, this distinction is not important in the emergency setting, but rather it is the recognition of a potentially serious dermatosis that is important.

The difference between TEN and SJS is defined by the extent of skin involvement. TEN affects more than 30% of the body surface area, whereas SJS affects 10% or less (Fig. 15.1.1). ‘TEN/SJS overlap’ refers to patients where there is between 10 and 30% body surface area involvement. The extent of necrolysis must be carefully evaluated since it is a major prognostic factor. Patients with HIV, collagen vascular disease and malignancy are at increased risk of TEN.

Clinical features

Clinical features of SJS/TEN include a prodrome with upper respiratory tract- (URTI) like symptoms, fever, malaise, vomiting and diarrhoea. Skin pain may herald the development of SJS/TEN and should not be dismissed. Symmetrical erythematous macules, mainly localized on the trunk and proximal limbs, evolve progressively to dusky erythema and confluent flaccid blisters leading to epidermal detachment.

The key to making the diagnosis is recognizing mucosal involvement, which may include conjunctival, oral mucosal, genital and sometimes perianal erosions, as well as an often severe haemorrhagic cheilitis. Gastrointestinal and respiratory mucosa can also be involved. Nikolsky sign is positive, that is dislodgement of the epidermis by lateral finger pressure in the vicinity of a lesion causes an erosion, or pressure on a bulla leads to lateral extension of the blister.

TEN is almost always due to drug ingestion which may, in rare instances, include illicit drug ingestion. Therefore, ask about prescribed and over-the-counter drugs, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), sulphonamides, allopurinol, nevirapine and anticonvulsants, such as sodium valproate and lamotrigine, as well as illicit drug use.

Investigations

Request a full blood count (FBC), urea and electrolytes (U&E), liver function tests (LFT) and a blood glucose. These may also be used to calculate the prognostic SCORTEN (see below). Other tests to consider include antinuclear antibody (ANA), extractable nuclear antigens (ENA), double stranded DNA (dsDNA), C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), anti-skin antibodies, HIV and mycoplasma serology. Skin swabs for viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and bacterial culture should be taken and chest X-ray (CXR), urine and blood cultures as indicated.

Biopsies are taken from the edge of a blister for histology and a perilesional site for immunofluorescence. Clearly state on the request slip that the differential diagnosis is of toxic epidermal necrolysis. Epidermal (keratinocyte) necrosis is the histological hallmark of this condition.

Management

Cease the triggering drug or agent immediately and involve the intensive care unit and/or the burns unit. Rapid institution of resuscitation measures is associated with a more favourable prognosis. Arrange assessment and treatment by the ophthalmology and ear, nose and throat teams for ocular and oral/pharyngeal involvement, respectively.

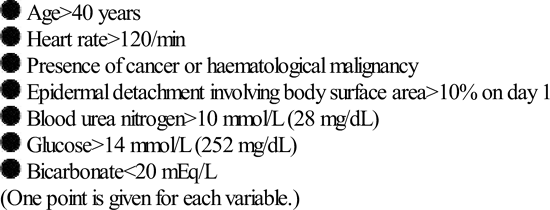

TEN may continue to evolve and extend over days, unlike a burn, where the initial insult occurs at a defined time. The SCORTEN severity scoring system for TEN (Table 15.1.3) is similar in concept to the Ranson’s score for pancreatitis. Calculate the SCORTEN severity score within 24 h of admission and again on day 3 to aid the prediction of possible death (Table 15.1.4).

Table 15.1.3

SCORTEN severity score for toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN)

Table 15.1.4

| Score | Mortality (%) |

| 0–1 | 3.2 |

| 2 | 12.1 |

| 3 | 35.3 |

| 4 | 58.3 |

| 5 or greater | 90.0 |

*Guegan S, Bastuji-Garin S, PoszepczynskaGuigne E, et al. Performance of the SCORTEN during the first five days of hospitalization to predict the prognosis of epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol 2006;126:272–6.

Erythema multiforme

While not life threatening, EM is part of the differential of a potentially life-threatening reaction, such as SJS/TEN. EM is an acute usually mild, self-limited cutaneous and/or mucocutaneous syndrome that presents with the rapid onset of lesions within a few days, favouring acral sites. These are often mildly pruritic or painful papular or urticarial lesions, as well as the classical ‘target’ lesions, but with only one mucous membrane involved (EM major) or none (EM minor). Typically, the oral mucosa is involved showing a few, discrete, mildly symptomatic erosions. Rarely, the eye, nasal, urethral or anal mucosa may be involved. A mild prodrome may precede development of the rash.

Most cases of EM are due to infection, most commonly Herpes simplex virus (HSV) or Mycoplasma. Drugs are now considered to be an uncommon cause (Fig. 15.1.2).

Investigations

Send a baseline FBC, U&E, LFT and CRP, as well as a skin biopsy if the diagnosis is uncertain, swabs and/or serology for HSV. Request a CXR and mycoplasma serology if there are respiratory symptoms.

Management

Usually, only symptomatic treatment is required with topical steroids, antihistamines, antiseptic mouthwashes and local anaesthetic preparations for oral involvement. For severe cases, treat erythema multiforme with a systemic steroid, such as predinosolone (0.5–1 mg/kg/day). In recurrent EM due to HSV, oral antivirals are effective.

Sweet’s syndrome

Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) may resemble severe EM in the acute oedematous phase, presenting with fever, arthralgia, neutrophilia and sterile, non-infective but painful pustules, plaques or nodules over the head, trunk and arms. It may recur and can be associated with inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis or other connective tissue diseases, haematological malignancy, such as myeloid leukaemia, pregnancy or infection, such as streptococcal or Yersinia (Fig. 15.1.3).

Sweet’s syndrome is highly responsive to systemic steroids, however, any underlying association must be sought and excluded by appropriate investigations.

Drug rash with eosinophilia (DRESS)

DRESS is a severe skin reaction with systemic manifestations that carries significant morbidity and a mortality rate of 10%. It usually occurs during the first prolonged course of a responsible associated drug, typically within 2–6 weeks of starting. It has been reported with the aromatic antiepileptics (phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbital), lamotrigine, sulphonamides (including sulphamethoxazole and trimethoprim combinations and dapsone), minocycline, allopurinol, terbinafine, abacavir and nevirapine. Up to 70% cross-reactivity occurs between different aromatic anticonvulsants which should therefore be avoided if someone has previously had a major reaction to an aromatic antiepileptic.

Fever and rash are the most common symptoms. Cutaneous involvement is often polymorphic usually starting as a maculopapular rash which may later become oedematous, exfoliative or erythrodermic and/or include non-follicular pustules. Often, rash involving the face indicates a more serious drug reaction and facial oedema and lymphadenopathy are frequent hallmarks of this syndrome.

Prominent eosinophilia is a characteristic feature that occurs in 60–70% of cases. Potentially serious internal organ involvement, such as hepatitis, nephritis, pneumonitis, myocarditis, thyroiditis, encephalitis and haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) syndrome, can occur. Fever, skin rash and organ involvement may fluctuate and persist for weeks or months after drug withdrawal, with the delayed onset of sequelae reported.

Investigations

Diagnosis can be difficult because of the polymorphic rash and variable organ involvement. A skin biopsy should be taken for histopathology and, although not diagnositic, histological features of a drug reaction will assist in making the diagnosis. Also request a basline FBC, U&E and LFT. Immunoglobulins and viral serology (Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), human herpesvirus 6 or 7 (HHV6, HHV7) should be sent, as transient hypogammaglobulinaemia and viral reactivation may be associated with fluctuations in symptoms. Other investigations should be as directed for systemic involvement.

Management

This usually includes admission to hospital and ceasing the suspected drug. Corticosteroids are first line of therapy despite no consensus on dose or regimen. Fluctuation in symptoms and relapse can occur when the dosage is tapered. As a result, steroid therapy sometimes has to be maintained for several weeks, even months and a steroid-sparing agent may be required. Antivirals and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) are emerging as potentially useful therapies for this condition. In milder cases, topical high-potency corticosteroids may be helpful for skin manifestations.

Erythroderma

The causes of erythroderma include eczema (40%), psoriasis (22%), drugs (15%), lymphoma (Sezary syndrome) (10%) and idiopathic (8%). Seek a history of previous skin disease, recent medications or recent changes to skin management, assess hydration and cardiac status, check for oedema, respiratory infection and a deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

Complications of erythroderma

Investigations

Send an FBC with film and differential, U&E, LFTs and blood cultures if the temperature is greater than 38°C, or if the patient appears unwell with rigors, even if the temperature is normal, as the patient may have become poikilothermic but is still septic.

Send skin swabs for microscopy and culture and request a chest X-ray. Arrange biopsy of the skin if the cause of the erythroderma is uncertain.

Management

Arrange to admit the patient. Treatment is general and supportive and includes:

attention to temperature control, avoiding hypothermia

attention to temperature control, avoiding hypothermia

referral to dietitian for high protein diet in the first 24 h

referral to dietitian for high protein diet in the first 24 h

bath oil daily in bath or shower

bath oil daily in bath or shower

50% white soft paraffin, 50% liquid paraffin all-over strictly every 6 h

50% white soft paraffin, 50% liquid paraffin all-over strictly every 6 h

Supervision should be under the direction of the dermatology team. Intensive care may be necessary.

Other bullous and vesicular conditions

There are many causes of blistering skin rashes that range from common and harmless (but still distressing) to the uncommon and potentially life threatening, such as TEN and SJS described above. See Table 15.1.5 for the differential diagnosis of a vesicobullous rash.

Table 15.1.5

Causes of a vesicular or bullous skin rash

Always ask about recent drug ingestion and also about drug allergy in the event that a bacterial skin infection is diagnosed and antibiotics are required.

Pemphigus vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is characterized by flaccid bullae and erosions, together with oral ulceration. The bullae often breakdown readily to form erosions as the split is epidermal. The Nikolsky sign is positive with dislodgement of the epidermis by lateral finger pressure in the vicinity of a lesion, causing an erosion or pressure on a bulla leading to lateral extension of the blister. Vegetating lesions, particularly in flexures, such as the axillae or on the scalp, may occur as ‘pemphigus vegetans’.

Investigations

Send blood for FBC, U&E, LFTs and glucose as a baseline and for thiopurine methyl-transferase (TPMT) levels, reduction of which increases the risk of toxicity if adjuvant immunosuppression with azathioprine is required.

Send a serum autoantibody profile for antiskin antibodies directed against a 130-kDa glycoprotein designated desmoglein 3 and located in desmosomes. Arrange biopsy of lesional skin for histology and perilesional skin, which should be sent fresh and not in formalin, for direct immunofluorescence. An alternative medium is Michel’s if fresh transport is not possible.

Management

Start high-dose prednisolone initially at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day to achieve remission (prior to the introduction of systemic steroids this disease was uniformly fatal). Admit the patient under the care of a dermatologist for consideration of other therapies, such as immunosuppression with azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, rituximab or cyclophosphamide. Plasmapheresis, intravenous gamma-globulin and rituximab may have an additive drug-sparing effect.

Bullous pemphigoid

The usual presentation is an elderly patient with tense skin bullae that may occur on an urticarial base, particularly in the axillae, medial thigh, groin, forearm and abdomen. Itch is a common accompaniment (Fig. 15.1.4).

Investigations

Send for FBC, electrolytes, LFTs and glucose level as a baseline, plus serum for indirect immunofluorescence for autoantibodies to Bullous pemphigoid antigens 1 or 2, components of the hemidesmosome. Also send a TPMT level, as adjuvant immunosuppression with azathioprine may be required. Arrange biopsy of an urticated or bullous lesion for histology and perilesional skin for direct immunofluorescence. If this is not possible, blister fluid may be sent for indirect immunofluorescence.

Management

Start prednisolone at a moderate dose, such as 0.5–0.75 mg/kg daily. A tetracycline antibiotic, such as doxycycline 100 mg daily and nicotinamide 500 micrograms orally tds, may be used for their anti-inflammatory properties as adjuvant therapy. Admit patients for supportive care if blistering is widespread.

In more severe disease, steroid-sparing agents, such as azathioprine, methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil, may be required. Super-potent topical steroids are also effective and may be used as monotherapy for localized disease.

Petechial and purpuric rashes

Petechiae, bruising and ecchymoses

Consider and exclude potentially life-threatening causes, such as thrombocytopaenia and vasculitis, platelet abnormalities such as those associated with thrombasthenia or uraemia, or over-anticoagulation (see Table 15.1.6 for causes of a petechial or purpuric rash). Take a full drug history, including anticoagulant medications, and ask about systemic symptoms including fever, bleeding tendency, travel history, alcohol abuse and known HIV disease.

Table 15.1.6

Causes of petechiae or purpura

| Non-palpable purpura | Palpable purpura (vasculitis) | ||||

| Non-thrombocytopaenic | Thrombocytopaenic disorders | ||||

| with splenomegaly | without splenomegaly | ||||

| Normal marrow | Abnormal marrow | Normal marrow | Abnormal marrow | ||

| Cutaneous disorders: Systemic disorders: |

Liver disease with portal hypertension Myeloproliferative disorders Lymphoproliferative disorders Hypersplenism |

Leukaemia Lymphoma Myeloid metaplasia | Immune: idiopathic thrombocytopaenic purpura, drugs, infections including HIV Non-immune: vasculitis, sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, haemolytic-uraemic syndrome, thrombotic thrombocytopaenic purpura |

Cytotoxics Aplasia, fibrosis or infiltration Alcohol, thiazides |

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) Leucocytoclastic (allergic) Henoch–Schönlein purpura Infective: Embolic |

‘Senile purpura’ are usually due to sun damage and ageing with subsequent loss of dermal support for blood vessels which then bleed into the skin. Sometimes they can be dramatic but are always benign and resolve. When simple trauma is considered, remember non-accidental injury in all cases where the history is suspicious, ‘hollow’ or changes over time.

Cutaneous vasculitis

There are many potential causes of cutaneous vasculitis, such as viral and bacterial infection, autoimmune and connective tissue diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis, systemic vasculitis, such as Wegener’s granulomatosis, polyarteritis nodosa and other causes that include inflammatory bowel diseases. Rarely, malignant tumours and leukaemia may present with vasculitis.

However, 50% of all cases of cutaneous small vessel vasculitis remain of undetermined aetiology or ‘idiopathic’ after extensive investigation and are presumed to be of post-infectious origin. Cutaneous vasculitis is clinically best diagnosed when lesions are palpable and on the lower limbs, although they may spread to the buttocks and arms (Fig. 15.1.5). Sharp edges with stellate or irregular shapes indicate full thickness ischaemia and are seen in septic embolic lesions or meningococcal infection and in thrombotic occlusion states, such as calciphilaxis in, for instance, chronic renal failure.

Pyoderma gangrenosum

Pyoderma gangrenosum is frequently a differential diagnosis of cutaneous vasculitis. It may begin as a discrete painful haemorrhagic pustule or grouped lesions that rapidly ulcerate, usually on the lower leg, causing larger lesions with neutrophilic inflammation with abscesses and necrosis, but not vasculitis on biopsy. It may be associated with inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, blood dyscrasias, Behçet’s syndrome and malignancy, such as myeloma and leukaemia (Fig. 15.1.6).

Investigations for vasculitis

Send blood for a vasculitis screen including FBC, ESR, CRP, U&E, LFTs, hepatitis B and C serology, ANA, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), antistreptolysin O (ASO) titre, cryoglobulin screen, anticardiolipin and antiphospholipid screen, serum protein electrophoresis and C3 and C4 complement levels.

Send two sets of blood cultures prior to any antibiotic therapy, such as ceftriaxone 2 g IV, if meningococcal infection is possible. Send a fresh urine specimen for phase contrast microscopy, looking specifically for glomerular red cells and casts indicating renal involvement (over 70% dysmorphic red cells or the presence of red cell casts indicate glomerular disease).

Arrange biopsy, although this is usually performed after admission or dermatology referral to clinic. Send a fresh specimen for both immunofluorescence (Henoch–Schönlein purpura suspected) and culture (infection suspected), as well as a specimen in formalin for histology.

Management

Potential triggers (see above) should be sought and treated appropriately. General measures include rest and elevation of the legs, supportive stockings and topical steroids. If systemic treatment is required, NSAIDs may be trialled before prednisolone. Antibiotics, steroids and cytotoxic immunosuppression are indicated based on the aetiology and severity of the disease, in consultation with a dermatologist.

Pruritic (itchy) dermatoses

Itch can be localized or generalized and may present with or without rash. While not an urgent problem, itch must be recognized as being distressing to the patient. The causes are many and varied and the prevalence of chronic itch (like chronic pain) increases with age. See Table 15.1.7 for causes of pruritus with or without skin disease.

Table 15.1.7

Causes of pruritus with, and without, skin disease

Urticaria

Urticaria may occur alone and be acute, relapsing or chronic (Fig. 15.1.7). It may also be a warning of impending anaphylaxis that necessitates immediate assessment for upper airway swelling, wheeze and/or hypotension (see Anaphylaxis, Chapter 2.8).

The causes of urticaria are heterogeneous and include immunological such as IgE-related, immune-complex or autoimmune; or non- immunological including physical such as cold, heat, sweating, exercise, pressure, sunlight, water and vibration; drug-related such as NSAIDs and radiocontrast media, or food and food additives. Or they they may be related to an underlying systemic condition such as infection including bacterial, viral, parasitic and fungal, systemic lupus erytematosus (SLE) or other vasculitis, malignancy including lymphoma, or urticaria pigmentosa (mastocytosis).

However, in many acute cases, no clear cause is found, ‘idiopathic’ and, in chronic urticaria, defined as lasting more than 6 weeks, frequently there is no known aetiology, although autoimmune causes are eventually found in 30–40%.

Scabies

Scabies must be excluded in the elderly patient with pruritus, particularly nursing home residents, and adolescents or young adults. This requires careful examination of web spaces, flexural wrist and the instep of the foot for scabies burrows and the penis and scrotum for nodules.

Crusted ‘Norwegian’ scabies is predisposed to by glucocorticoid therapy, organ transplant and HIV infection and in the elderly. It is usually not particularly itchy, but an affected patient who is infested with countless mites is often the source of large-scale outbreaks in nursing homes and hospitals (Fig. 15.1.8).

Tinea

Tinea incognito refers to tinea corporis which has been suppressed and modified in appearance due to the inappropriate use of topical steroids. The topical steroid suppresses the erythema and allows for excessive growth of the causative fungus.

Investigations for pruritus

iron studies and ferritin level if there is a hypochromic, microcytic blood picture

iron studies and ferritin level if there is a hypochromic, microcytic blood picture

glucose level to screen for diabetes

glucose level to screen for diabetes

urea, electrolytes and creatinine to exclude renal failure

urea, electrolytes and creatinine to exclude renal failure

thyroid stimulating hormone to exclude hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism

thyroid stimulating hormone to exclude hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism

coeliac serology, such as IgA tissue transglutaminase (IgA tTG) antibodies.

coeliac serology, such as IgA tissue transglutaminase (IgA tTG) antibodies.

Take skin scrapes from any suspicious areas for fungal culture and microscopy. In suspected scabies, send material to look for scabies mites, eggs or faeces on microscopy.

Management

General measures include avoiding triggers, in particular overheating, and rehydrating the skin with an emollient, such as aqueous cream combined with an anti-itch preparation (0.5% menthol). Prescribe an antihistamine for short-term use, particularly if sleep is impaired, such as promethazine 10 mg 8-hourly or chlorpheniramine 4 mg 6-hourly, with a clear warning to avoid alcohol and not to drive or operate machinery.

Attempt to identify a cause in every case. Resist giving prednisolone for an itchy dermatosis when no cause has been identified. Arrange appropriate investigations and refer the patient for dermatological follow up to avoid missing a treatable but otherwise chronic condition, such as dermatitis herpetiformis from gluten sensitivity.

Eczema and psoriasis

Eczema

Atopic eczema is a common skin complaint often affecting the flexures (Fig. 15.1.9). It may present as an emergency in a number of ways. See Table 15.1.8 for an overview of aetiology, clinical features and management principles.

Table 15.1.8

Atopic eczema: acute attacks and complications

| Infective eczema | Erythroderma | Acute eczema | |||

| Eczema herpeticum | Impetiginized eczema | Unstable eczema | Psychological | Contact | |

| Cause | Infection with herpes simplex, Varicella, which can rapidly disseminate over the skin | Staphylococcal | Due to many factors systemic or external |

Stressors | Allergen? |

| Examination | Grouped locally or generally Pinhead-sized papules or vesicles Clear or closed pustules Excoriated sharply defined circular erosions |

Discharge and weeping Yellow and crusted blisters or erosions |

Total body redness Scale or weeping. Pruritus Hypothermia. Fever, sepsis |

Severe Red Pruritus Disturbed sleep |

Sharp edges Localized |

| Management | Antivirals if severe, early and eyes at risk | Oral antibiotics. Antiseptic (triclosan) soaks and wet dressings | Admission Oral steroids Ciclosporin |

Admission topicals Oral steroids Paraffin, etc. |

Oral steroids Admission |

Eczema is one of the most common causes of erythroderma. See earlier for management principles, which should always involve a dermatologist and may require intensive care unit admission.

Discoid eczema

Discoid eczema presents as discrete coin-like or ‘nummular’ erythematous plaques that may develop significant exudate and crusting. ‘Satellite’ lesions are common and skin involvement is often progressive, as one area of involvement ‘drives’ other areas of skin to become eczematous.

Investigation

Take swabs to exclude staphylococcal super-infection.

Management

Prescribe a potent topical steroid, such as mometasone 0.1% or betamethasone 0.1% cream or ointment. Advise the patient that more than 1 week of daily or twice daily application may be required and that lesions will tend to recur at the same site. Relapses should be treated in the same manner. Topical coal tar preparations may be used as a steroid alternative, such as 5–10% coal tar in either white soft paraffin or aqueous cream. Preparations are also available as a shampoo.

Allergic contact dermatitis

Allergy to plants typically presents in a ‘streaky’ or linear pattern. A severe facial flare of eczema may suggest an airborne allergen as a trigger. The use of hair dyes following a ‘henna tattoo’ (which may have been applied months or years before) can result in severe scalp and facial dermatitis, as henna used on hair is adulterated with paraphenylene diamine. The patient becomes sensitized to this compound, which is found in most hair dyes.

Some allergens are activated by the ultraviolet (UV) in sunlight to become symptomatic. This occurs in phytophotodermatitis (often a streaky or linear dermatitis on exposed areas that may be blistered or hyperpigmented) which is seen after contact with photosensitising compounds found naturally in some plants, fruit and vegetables. Nickel sensitivity is a common cause of reactions to jewellery, particularly costume jewellery and, occasionally, to the clasp of a bra. These causes may or may not be obvious to the patient, so a careful focused history is essential.

Irritant contact dermatitis

The hands are commonly involved and may become secondarily infected. Patients may be severely incapacitated if both hands are affected and may need admission. Patients commonly have an atopic background, especially atopic eczema. Ask the patient how many times they wash their hands each day, as irritant contact dermatitis may be one of the first signs of an obsessive–compulsive disorder.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis may present acutely in the following patterns:

Pustular psoriasis: triggered by systemic or external factors, including pregnancy, topical treatments, medication and oral steroids. Examination reveals yellow sterile pustules on plaques, diffuse generalized (Fig. 15.1.10) or localized red areas beginning around the paronychium of the digits or pulp. Arthritis may be present and consider Reiter’s syndrome if there is a history of gastrointestinal or genitourinary symptoms. Hypocalcaemia may develop if the pustular psoriasis is generalized.

Pustular psoriasis: triggered by systemic or external factors, including pregnancy, topical treatments, medication and oral steroids. Examination reveals yellow sterile pustules on plaques, diffuse generalized (Fig. 15.1.10) or localized red areas beginning around the paronychium of the digits or pulp. Arthritis may be present and consider Reiter’s syndrome if there is a history of gastrointestinal or genitourinary symptoms. Hypocalcaemia may develop if the pustular psoriasis is generalized.

Investigations for acute psoriasis

Send blood for FBC, U&E and LFTs, including a serum calcium (which may be low with pustular psoriasis). Send other investigations for systemic complications such as infection, including a skin swab and/or blood cultures, as well as monitoring for the side effects of therapy. A skin biopsy is usually performed in the ward or dermatology clinic if the diagnosis is in doubt.

Management

Treatments include UV therapy, methotrexate, ciclosporin, acitretin or antitumour necrosis factor (TNF) therapy, such as etanercept or infliximab. These all require a dermatology consultation and careful review of past treatment. Admission is required if the patient has extensive areas involved, is systemically unwell or unable to manage at home.

Older treatments, such as Ingram’s or Goerkerman’s regimens, used the combination of dithranol or coal tar respectively, and UV phototherapy. They can be particularly effective, have low toxicity and may therefore be considered as one option for patients. Rotating therapies in psoriasis may be beneficial and a past treatment failure does not necessarily indicate that treatment will always be ineffective.

Other dermatoses

Skin cancer

Patients may present to an ED with lesions they, or a concerned family member or partner, are worried about. Important differential diagnoses not to miss include melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer, including squamous cell and basal cell carcinoma. Refer the patient for prompt assessment by a dermatologist if the lesion looks suspicious, which will usually require a biopsy.

Eczema herpeticum

Eczema herpeticum is widespread herpes simplex infection complicating a pre-existing skin disease, most often atopic eczema. Consider this in any patient with an acute flare of eczema, particularly if the skin is painful. It presents as an acute eruption of monomorphic vesicles and/or erosions often with purulent exudate and crusting, not necessarily with herpetiform grouping.

A preceding herpetic cold sore may or may not have been present. Some episodes present as a severe systemic illness with high fever, malaise and a widespread generalized eruption. However, there may be no systemic disturbance and the eruption may be quite localized, often to areas of pre-existing eczema.

Ocular HSV infection should be suspected if there is periorbital involvement or if ocular symptoms are present, such as eyelid oedema, tearing, photophobia, chemosis or preauricular lymphadenopathy, whether the eruption involves the face or not. An urgent ophthalmology opinion should be sought for complications, such as corneal ulceration, scarring and blindness.

Investigations

Viral swabs for PCR should be taken of vesicle fluid or the base of an erosion to confirm the diagnosis of HSV. Bacterial superinfection is common, so send a swab for bacterial M, C&S as well.

Management

Antiviral therapy is essential, such as acyclovir 400 mg 5 times daily for 7 days or valaciclovir 1 g bd for 7 days. Antiviral prophylaxis may be required for recurrent attacks. If secondary bacterial infection is suspected, start an antistaphylococcal antibiotic, such as cephalexin 500 mg qid for 5 days. Optimizing the management of eczema is also important.

Herpes zoster

The first manifestation of herpes zoster (HZV) is usually pain, which may be severe and accompanied by fever, headache, malaise and regional lymphadenopathy. Closely grouped red papules evolve to classical vesicles and then often pustules, in a dermatomal distribution. Rarely, the eruption may be multidermatomal or bilateral, particularly if the patient is immunosuppressed.

Diagnosis can be a challenge unless the dermatomal distribution of the eruption is appreciated. Vesicles on the side of the nose indicate involvement of the nasociliary branch of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve, which also innervates the cornea. Nasal herpetic infection (Hutchinson’s sign) may precede or accompany ophthalmic involvement, which necessitates urgent ophthalmologic referral. Vesicles within the external auditory meatus associated with deep ear pain and lower motor neuron facial nerve palsy is the classic triad of Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Early diagnosis and treatment with oral prednisolone and antivirals is indicated.

Investigations

Take swabs for bacteriology and viral polymerase chain reaction for HZV to confirm the diagnosis.

Management

Prompt treatment with antiviral medication, such as acyclovir 800 mg orally five times a day or famciclovir 250 mg orally tds, when seen within 72 h of vesicle eruption, may prevent post-herpetic neuralgia.