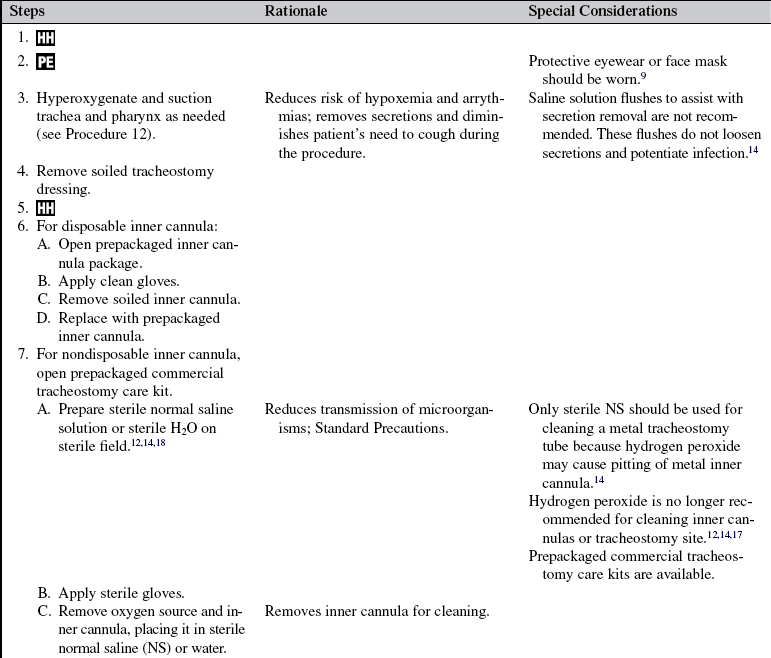

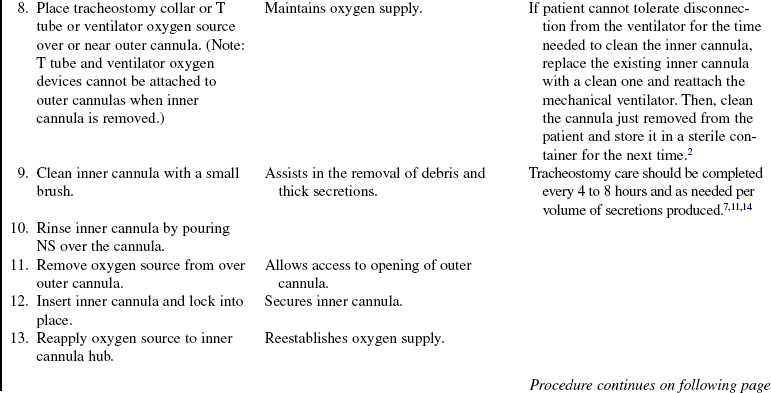

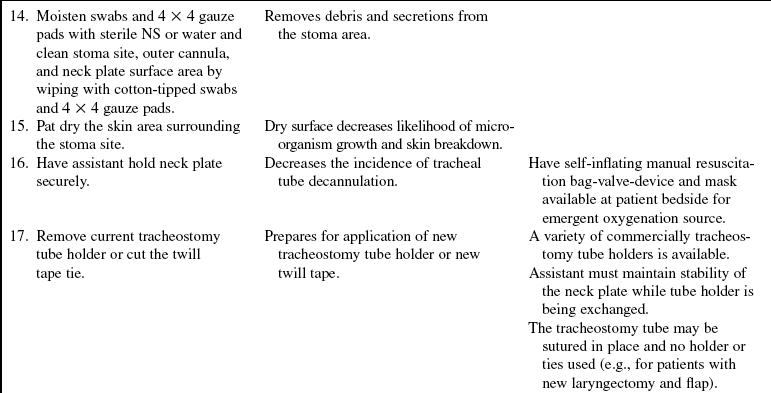

Tracheostomy Tube Care

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

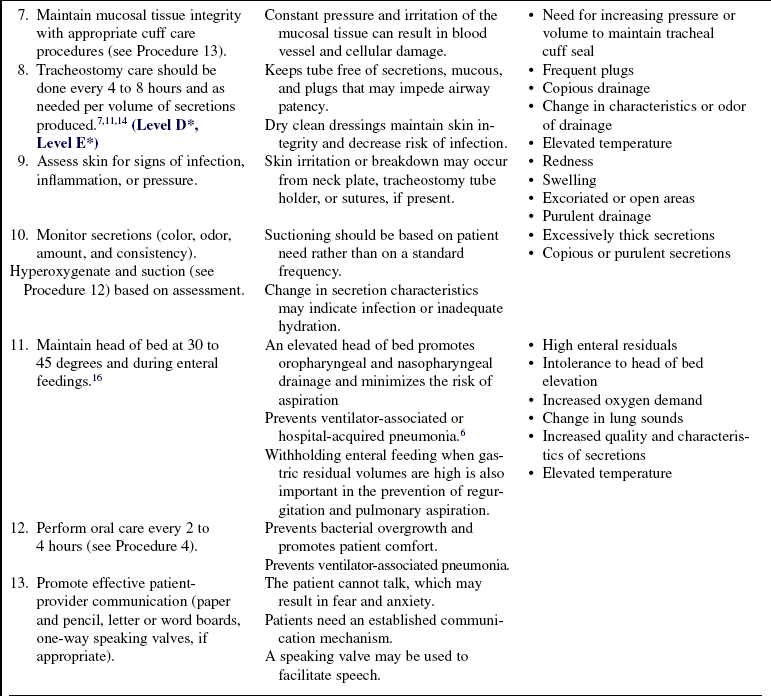

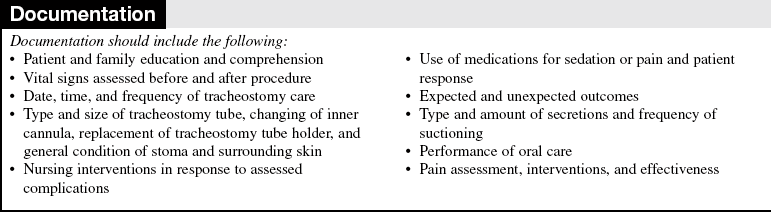

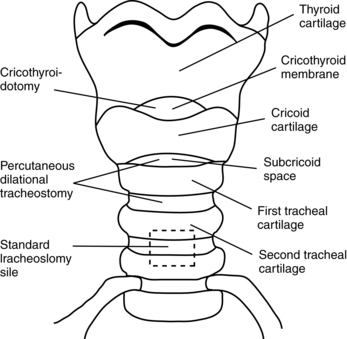

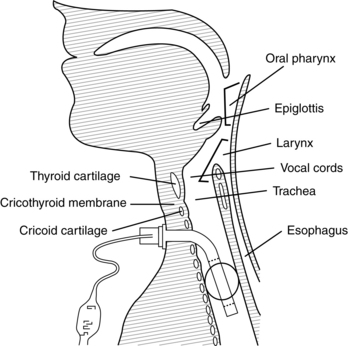

• Tracheotomy refers to the surgical procedure in which an incision is made below the cricoid cartilage through the second to fourth tracheal rings (Fig. 14-1). Tracheostomy refers to the opening, or stoma, made by the incision. The tracheostomy tube is the artificial airway inserted into the trachea during tracheotomy (Fig. 14-2).

Figure 14-1 Sites for tracheostomy insertion. (From Serra A: Tracheostomy care, Nurs Stand 14:42,45-52, 2000.)

Figure 14-2 A tracheostomy (sometimes called a tracheotomy) is created surgically by making an opening through the skin of the neck into the trachea. (Serra A: Tracheostomy care, Nurs Stand 14:42,45-52, 2000.)

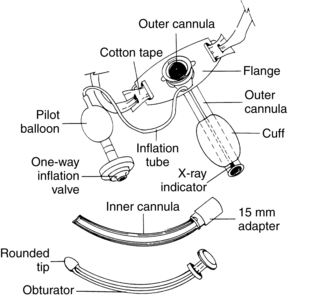

• Tracheostomy tubes have a variety of parts (Fig. 14-3) and are available in various sizes and styles from several manufacturers. The tubes can be metal or plastic, with standard or extra length. Clinicians who care for patients with tracheostomy tubes must understand the differences and select a tube that appropriately fits the patient and clinical condition. A tracheostomy tube is shorter than but similar in diameter to an endotracheal tube and has a squared-off distal tip for maximization of airflow. The outer cannula forms the body of a tracheostomy tube with a cuff. The neck flange, attached to the outer cannula, assists in stabilizing the tube in the trachea and provides the small holes necessary for proper securing of the tube. Some tracheostomy setups have an inner cannula inserted into the outer cannula. The inner cannula is removable for easy cleaning without airway compromise. The cuff is a balloon inflated with air to maintain a seal around the tube. As the air flows through the one-way inflation valve, the pilot balloon inflates, which indicates the volume of air present in the cuff.

• A cuffed tube is appropriate for use in patients who need mechanical ventilation or for whom aspiration is a problem. The cuff limits aspiration of oral and gastric secretions. Uncuffed tubes are commonly used in children, in adults with laryngectomies, and during decannulation of the tracheostomy. A fenestrated tracheostomy tube has an opening in the curvature of the posterior wall of the outer cannula. The matching fenestrated inner cannula is inserted into the outer cannula. Fenestrated tracheostomy tubes are useful for patients with smaller tracheas and during weaning.12 With cuff deflation, options for speech are finger occlusion technique, placement of a speaking valve (Passy-Muir valve), or capping of the outer cannula; all permit air to flow through the upper airway and tracheostomy opening. Foam cuff tracheostomy tubes consist of a high-volume cuff and are composed of polyurethane foam covered with a silicone sheath. Despite the long availability of this type of tracheostomy tube, it is not commonly used and is usually reserved for patients who already have tracheal injury related to the cuff.

• A tracheotomy is performed as either an elective procedure or an emergency procedure for a variety of reasons (Table 14-1). Most often, the procedure is elective and performed in the operating room with sterile conditions. An emergency tracheotomy is performed at the bedside with aseptic technique or before arrival in the critical care unit when swelling, injury, or other upper airway obstruction prevents intubation with an endotracheal tube. Percutaneous tracheotomies also are performed at the bedside. Minimally invasive percutaneous tracheotomy was introduced recently as an alternative to the traditional surgical technique. It has gained widespread acceptance in the past decade.5,8 This procedure consists of passing a needle into the trachea, placing a J-tipped guidewire, progressively dilating the trachea, and placing the tracheostomy tube. The percutaneous procedure has achieved outcomes comparable with outcomes with the surgical technique.1,3

Table 14-1

Bypass acute upper airway obstruction

Prolonged need for artificial airway

Prophylaxis for anticipated airway problems

Reduction of anatomic dead space

Prevention of pulmonary aspiration

Retained tracheobronchial secretions

Chronic upper airway obstruction

• Protocols for emergency tracheotomy vary among institutions. Often, nurses at the bedside take an active role in assisting with tracheotomy and insertion of a tracheostomy tube; however, some institutions have surgical personnel at the bedside to assist with the procedure.

• During insertion, the obturator replaces the inner cannula. Its smooth surface protrudes from the outer cannula and minimizes tracheal trauma. When the tracheostomy tube is inserted, the obturator is removed and replaced with the inner cannula, which locks in place. The same size sterile tracheostomy tube should be available at the bedside for easy access in case of accidental decannulation.

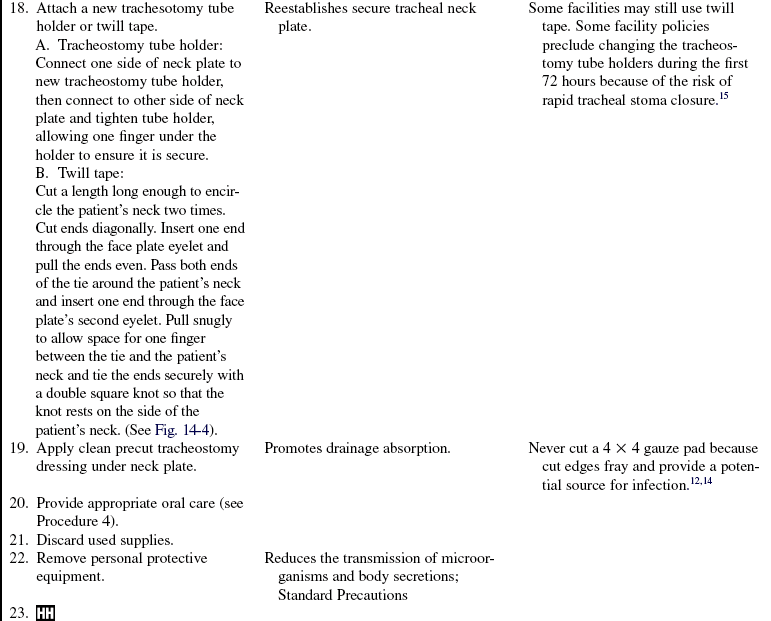

• The decision for a tracheotomy in patients with long-term mechanical ventilation is made on the basis of the team’s projection regarding length of time that mechanical ventilation or an artificial airway is required. A tracheostomy tube is the preferred method of airway maintenance in a patient who needs intubation for more than 14 to 21 days. Each case must be reviewed individually.1,3,10,13,14 Better predictors are needed to further identify patients who can benefit from tracheotomy early in the course of mechanical ventilation.8

• When compared with endotracheal tubes, tracheostomy tubes provide added benefits to patients, including the following:

Prevention of further laryngeal injury from the translaryngeal tube

Prevention of further laryngeal injury from the translaryngeal tube

Improved patient comfort, acceptance, and toleration

Improved patient comfort, acceptance, and toleration

Decreased work of breathing because of less airflow resistance

Decreased work of breathing because of less airflow resistance

Facilitation of weaning from mechanical ventilation

Facilitation of weaning from mechanical ventilation

Decreased requirement for sedation

Decreased requirement for sedation

Provision of a speech mechanism

Provision of a speech mechanism

• A tracheostomy tube is viewed by the body as foreign material. The body responds by increasing mucus production. Also, ciliary movement is impaired, which limits the forward movement of the mucociliary escalator. Because the tracheostomy bypasses the upper airway and its protective and hydrating mechanisms, patients are at increased risk of infection. Lack of hydration by the upper airway can lead to thick mucus, which increases the risk of airway obstruction. Tracheostomy patients should receive continuous humidified air or oxygen for this reason.1,4

• The tracheostomy tube creates a more stable airway, making transfer out of the critical care unit feasible when overall patient condition warrants. Also, care of the patient, such as suctioning, oral care, and ability to meet nutritional needs, is simplified.

• A stoma less than 48 hours old has not fully formed a tracheostomy tract. If the tracheostomy tube is accidentally dislodged, the tracheostomy may close and compromise the patient’s airway.

• A small amount of bleeding is expected for the first few days after a tracheotomy. Bright frank bleeding or constant oozing is not expected and should be brought to the attention of the physician or advanced practice nurse.

• Consideration should be given to obtaining assistance with tracheostomy care, especially when tracheal ties are changed or a patient is agitated. An extra pair of hands can minimize the risk for accidental dislodgment.

EQUIPMENT

• Personal protective equipment

• Sterile normal saline solution (NS) or water

• Commericial tracheostomy tube holder

• Sterile precut tracheostomy dressing

• Sterile disposable inner cannula of the same size

• Self-inflating manual resuscitation bag-valve-device and mask

Additional equipment (to have available based on patient need) includes the following:

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the purpose and the necessity of the tracheotomy or tracheostomy care. Involve patient and family members in ongoing education, particularly if a home discharge with the tracheostomy is anticipated.  Rationale: Education to the patient and family encourages cooperation and compliance and reduces anxiety.

Rationale: Education to the patient and family encourages cooperation and compliance and reduces anxiety.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Assess increased production of secretions.  Rationale: Tube irritation to mucosa results in increased production of secretions.

Rationale: Tube irritation to mucosa results in increased production of secretions.

• Assess cardiopulmonary status:

•  Rationale: Evaluation of the patient’s cardiopulmonary status provides valuable information about the need for and tolerance of tracheostomy tube care.

Rationale: Evaluation of the patient’s cardiopulmonary status provides valuable information about the need for and tolerance of tracheostomy tube care.

Patient Preparation

• Verify the correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale:. Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale:. Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Perform a pre-procedure verification and time out, if non-emergent.  Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

• Ensure that the patient understands preprocedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: This communication evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

Rationale: This communication evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

References

![]() 1. Billau, C. Suctioning. In: Russell C, Matta B, eds. Tracheostomy a multiprofessional handbook. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004:157–171.

1. Billau, C. Suctioning. In: Russell C, Matta B, eds. Tracheostomy a multiprofessional handbook. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004:157–171.

![]() 2. Buchfa, VL, Fries, CM, Repiratory care in nursing procedures. ed 3. Springhouse Corp, Springhouse, PA, 2000:449–455.

2. Buchfa, VL, Fries, CM, Repiratory care in nursing procedures. ed 3. Springhouse Corp, Springhouse, PA, 2000:449–455.

![]() 3. Burns, SM, et al. Are frequent inner cannula changes necessary? A pilot study. Heart Lung. 1998; 27:58–62.

3. Burns, SM, et al. Are frequent inner cannula changes necessary? A pilot study. Heart Lung. 1998; 27:58–62.

![]() 4. Henneman, E, Ellstrom, K, St John RE, Airway management. In AACN protocols for practice: care of the mechanically ventilated patient series. American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, Aliso Viejo, CA, 1999.

4. Henneman, E, Ellstrom, K, St John RE, Airway management. In AACN protocols for practice: care of the mechanically ventilated patient series. American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, Aliso Viejo, CA, 1999.

5. Hess, D. Tracheostomy tubes and related appliances. Respir Care. 2005; 50(4):497–509.

![]() 6. Hubmayr, RD, Burchardi, H, Elliot, M, et al. American Thoracic Society Assembly on Critical Care, European Respiratory Society, European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, Societe de Reanimation de Langue Francaise. Statement of the 4th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care on ICU-Acquired Pneumonia, Chicago, Illinois, May 2002. Intensive Care Med. 2002; 28:1521–1536.

6. Hubmayr, RD, Burchardi, H, Elliot, M, et al. American Thoracic Society Assembly on Critical Care, European Respiratory Society, European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, Societe de Reanimation de Langue Francaise. Statement of the 4th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care on ICU-Acquired Pneumonia, Chicago, Illinois, May 2002. Intensive Care Med. 2002; 28:1521–1536.

![]() 7. McCloskey, J, Bulechek, G. Nursing interventions classification, ed 3. St Louis: Mosby; 2002.

7. McCloskey, J, Bulechek, G. Nursing interventions classification, ed 3. St Louis: Mosby; 2002.

![]() 8. Mittendorf, EA, et al. Early and late outcome of bedside percutaneous tracheostomy in the intensive care unit. Am Surg. 2002; 68:342–346.

8. Mittendorf, EA, et al. Early and late outcome of bedside percutaneous tracheostomy in the intensive care unit. Am Surg. 2002; 68:342–346.

9. Potter, P, Perry, A, Fundamentals of nursing. Mosby, St Louis, 2009:946–950.

10. Rana, S, Pendem, S, Pogodzinski, M, et al. Tracheostomy in critically ill patients. Mayo Clini Proce. 2005; 80(12):1632–1638.

![]() 11. Rankin, N. What is optimum humidity. Respir Care Clin North Am. 1998; 4:321–328.

11. Rankin, N. What is optimum humidity. Respir Care Clin North Am. 1998; 4:321–328.

12. Roman, M. Tracheostomy tubes. Medsurg Nurs. 2005; 14(2):143–145.

13. Russell, C. Providing the nurse with a guide to tracheostomy care and management. Br J Nurs. 2005; 14(8):428–433.

![]() 14. St John R, Protocols for practice. airway management. Crit Care Nurs. 2004; 24(2):93–96.

14. St John R, Protocols for practice. airway management. Crit Care Nurs. 2004; 24(2):93–96.

![]() 15. Seay, S, Gay, S, Strauss, M. Tracheostomy emergencies. Am J Nursing. 2002; 102(3):59–61.

15. Seay, S, Gay, S, Strauss, M. Tracheostomy emergencies. Am J Nursing. 2002; 102(3):59–61.

16. Tolentino, AF, Ruppert, SD, Shiao, SY : Evidence-basedpractice: Use of the ventilator bundle to prevent ventilatorassociated pneumonia, Am J Crit Care, 16( 1): 20- 2007

![]() 17. Trundle, C, Brooks, R, Infection control issues in the care of a patient with a tracheostomy. In Tracheostomy a multiprofessional handbook. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004:343–360.

17. Trundle, C, Brooks, R, Infection control issues in the care of a patient with a tracheostomy. In Tracheostomy a multiprofessional handbook. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004:343–360.

18. Winn, M, Right, K, Tracheostomy. a guide to nursing care. Austr Nurs. 2005; 13(5):1–4.

Plambeck, A. Adult ventilation management, Corexcel, Inc. www.corexcel.com/courses/vent.htm, 2004. [retrieved 10/28/09, from].

St John R, Seckel, M, Airway managementBurns S, ed.. Care of the mechanically ventilated patients. MA. ed 2. Jones and Bartlett, Sudbury, 2007.

Serra, A. Tracheostomy care. Nurs Stand. 2000; 14:42,45–52.

Tamburri, LM. Care of the patient with a tracheostomy. Orthop Nurs. 2000; 19:49–58.

Thompson, J, McFarland G, Hirsch J, et al. Ear, nose and throat. Mosby’s clinical nursing. 2002; 627–630.