Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Emergencies

Edited by Anthony Brown

14.1 Rheumatological emergencies

Michael J Gingold, Adam B Bystrzycki and Flavia M Cicuttini

Introduction

Rheumatological conditions are common and encompass inflammatory or connective tissue diseases and mechanical/musculoskeletal conditions. Life-threatening emergencies are rare and relate to either the underlying condition or its treatment. The challenge is in making the distinction between the two, as treatment is frequently diametrically opposed; for example, the difference between administering further immunosuppression and giving antibiotics.

The most common rheumatological emergency seen in the emergency department (ED) is acute monoarthritis (see Chapter 14.2). This chapter discusses the important general emergencies associated with rheumatological conditions. Many of these are multisystem diseases and emergencies relate to either a primary joint problem, an extra-articular manifestation or sometimes to the drugs used in management.

Many of these conditions are autoimmune, thus immunosuppression is usually central to their management making infection a frequent complication. More targeted, so-called biological therapies, which inhibit proinflammatory cytokines as well as B- and T-cell activity have been developed. They carry their own set of potential complications, again including infection.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) affects 1–2% of the population across most ethnic subgroups and is two to three times more common in females than males. RA is a systemic inflammatory condition of unknown aetiology characterized by widespread synovitis resulting in joint erosions and destruction. It may also produce extra-articular manifestations including vasculitis and visceral involvement.

Management typically involves symptom relief with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and/or corticosteroids and early initiation of conventional disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). These include methotrexate, leflunomide, sulphasalazine and hydroxychloroquine and, if these agents fail to control disease progression, biological agents are commenced. The latter act by inhibiting tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, golimumab, certolizumab pegol), interleukin-6 (IL-6) (tocilizumab), T-cell co-stimulation (abatacept) or by depleting B cells (rituximab). See Chapter 14.3 for further details on the clinical features of RA, its diagnosis, investigation and management.

Articular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis

Acute monoarthritis

A patient with established RA may present with an acutely painful, hot, swollen joint that may be due to the underlying condition or, alternatively it may be due to a septic arthritis. Patients with RA are two to three times more susceptible than matched controls [1]. The risk is approximately twofold higher again in RA patients on TNF-α inhibitors compared to RA patients on conventional DMARDs [2]. Thus, the possibility of septic arthritis must be considered in a patient with RA who has acute monoarthritis out of keeping with their disease activity. See Chapter 14.2 for an approach to acute monoarthritis.

Cervical spine involvement

Cervical spine involvement in RA is common with a prevalence of up to 61%. It is more likely in those with long-standing, erosive disease and disease of greater severity and activity [3]. Cervical spine involvement is associated with increased mortality [4] and may manifest as atlanto-axial subluxation (most commonly anterior movement on the axis) or subluxation of lower cervical vertebrae. Either of these can result in cervical myelopathy.

Cervical spine subluxation is often asymptomatic – up to 44% in one study [3]. The most common symptom is neck pain that may radiate towards the occiput. Other suggestive symptoms include sensory loss in hands or feet, paraesthesia or weakness in the distribution of cervical nerve roots and slowly progressive spastic quadriparesis.

Important ‘red flags’ suggesting cervical myelopathy are listed in Table 14.1.1.

Table 14.1.1

Symptoms and signs of cervical myelopathy

Symptoms

Pain

Weakness

Peripheral paraesthesia

Gait disturbance

Sphincter dysfunction

Changes in consciousness

Respiratory dysfunction

Signs

Spasticity

Weakness

Hyperreflexia of deep tendon reflexes

Extensor plantar response

Gait ataxia

Respiratory irregularity

Imaging

Plain X-rays of the cervical spine (lateral view) may demonstrate an increase in separation between the odontoid and arch of C1. Prior to taking flexion–extension films, perform plain ‘peg’ X-rays through the open mouth to exclude odontoid fracture or severe atlanto-axial subluxation. Computed tomography (CT) can provide additional useful information, although if there is concern regarding myelopathy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more sensitive.

Management

The main implication of RA of the cervical spine in the ED is when endotracheal intubation is required. Excessive manipulation (neck flexion with head extension) of the rheumatoid cervical spine in preparation for intubation can result in significant morbidity and even mortality from atlanto-axial and subaxial subluxation.

Whenever possible, a patient with RA who is scheduled to undergo surgery should have imaging of his or her cervical spine prior to endotracheal intubation. Anaesthetic consultation is recommended.

Patients with subluxation and signs of spinal cord compression represent a neurosurgical emergency and prompt referral is essential.

Extra-articular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid vasculitis

Vasculitis in RA can occur in both small- and medium-sized vessels. Patients typically have long-standing, aggressive joint disease. This presentation, although important, is becoming less frequent.

Clinical features

Rheumatoid vasculitis presentations are varied and non-specific. Patients frequently have constitutional symptoms and fatigue. The most common manifestation is cutaneous vasculitis with deep skin ulcers on the lower limbs [5], digital ischaemia and gangrene (medium vessels) or palpable purpura (small vessels). Mononeuritis multiplex is another frequent presentation resulting from vasculitic infarction of the vasa nervorum, which typically has an acute onset.

Medium vessel rheumatoid vasculitis may cause organ infarction and necrosis. Rheumatoid vasculitis can mimic polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) with involvement of the renal arteries and, less commonly, the mesenteric circulation. Pericarditis may accompany rheumatoid vasculitis, but coronary vasculitis is rare. Ocular manifestations include episcleritis and peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement is rare.

Investigations

Rheumatoid factor titre is typically elevated in rheumatoid vasculitis, although this is a non-specific finding. Rheumatoid vasculitis in the absence of rheumatoid factor is rare. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are also elevated. Check a full blood count, urea and electrolytes and a midstream urine specimen for active urinary sediment including abnormal red cells or casts, as well as infection.

Further investigations are directed at the relevant organ system involved usually after specialist consultation:

Angiography findings are non-specific and not always diagnostic.

Diagnosis

Suspect rheumatoid vasculitis in patients with a long-standing history of seropositive RA who presents with constitutional symptoms and one of the above features, such as a typical rash, digital gangrene, red eye, neurological complaint or an active urinary sediment.

Management

Systemic rheumatoid vasculitis has a poor prognosis without immune-suppressive therapy. Urgent rheumatology consultation is required as treatment usually consists of high-dose corticosteroids as well as cyclophosphamide, often necessitating hospital admission.

Other extra-articular manifestations of RA

Pulmonary disease

Pulmonary manifestations include pleural-based disease, such as pleurisy or pleural effusions, or parenchymal disease, such as interstitial lung disease (the most common manifestation), organizing pneumonia and rheumatoid nodules. Caplan’s syndrome occurs when RA is associated with pneumoconiosis. Important differential diagnoses include infection due to immune suppression, treatment-related toxicity, such as methotrexate-induced pneumonitis, and other medical co-morbidities including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Pleural disease often resolves without treatment, although an NSAID may be used symptomatically. Parenchymal disease documented on chest X-ray or high-resolution CT requires specialist treatment.

Cardiac disease

Pericarditis occurs in 30% of RA patients based on echocardiography, but less than 10% have clinical features. It generally presents when there is active joint and other extra-articular disease and management consists of NSAIDs or prednisolone.

Myocarditis is a rare manifestation of RA. It may be granulomatous and, depending on its location, can produce valvular (especially mitral) incompetence or conduction defects.

Sjögren’s syndrome

Sjögren’s syndrome may present in a primary form as a systemic disease, but can also occur secondary to RA and other connective tissue disorders. The classic symptoms are dry gritty eyes, dry mouth or both. Treatment is usually symptomatic in patients with no other features.

Felty’s syndrome

Felty’s syndrome is characterized by seropositive RA, splenomegaly and neutropaenia. There may be other cytopaenias, as well as leg ulcers, and infection is a risk.

Renal disease

Renal involvement with RA is rare and includes vasculitis and glomerulonephritis. Secondary amyloidosis can occur in patients with long-standing active disease. However, many medications used in RA are nephrotoxic, in particular NSAIDs and ciclosporin.

Neurological disease

Vasculitis may produce mononeuritis multiplex, otherwise central nervous system involvement is rare.

Ischaemic heart disease in RA and other connective tissue diseases

Patients with RA and other connective tissue diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), have an increased risk of ischaemic heart disease (IHD) [6]. This occurs independently of traditional risk factors, such as smoking, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, etc. and is more common in those with extra- articular disease [7]. The higher incidence of IHD appears related to disease factors, such as widespread inflammation, but medications, such as NSAIDs (including selective COX-2 inhibitors) and corticosteroids, may play a role.

Thus there should be a heightened awareness when ruling out ischaemic chest pain in the RA patient. Cardiac investigations are no different to those undertaken for non-RA patients and a patient with a history suggestive of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) but negative serial cardiac biomarkers and electrocardiograms must proceed to provocative testing. Management of ACS in RA is no different (see Chapter 5.2).

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a multisystem, autoimmune disease. It is the prototype disease of immune complex deposition resulting in tissue damage across a wide range of organ systems and one of the most common autoimmune conditions in women of childbearing age.

Clinical features

Common presenting features of SLE include general constitutional symptoms, such as fatigue, malaise and weight loss. There is a variety of skin manifestations in SLE which are lupus-specific (malar rash, discoid lupus, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus) or non-specific (panniculitis, alopecia, oral ulceration). Arthralgias or an acute non-erosive arthritis are the most common presenting symptoms of SLE.

Another common manifestation is serositis causing pleurisy, pericarditis or peritonitis. SLE also causes renal and CNS disease (see below) and, rarely, can involve the lung parenchyma (pneumonitis, pulmonary hypertension) and heart (myocarditis, endocarditis). Myositis may also occur.

Investigations

A full blood examination often reveals cytopaenias which are a common feature of SLE. Biochemistry may indicate renal impairment. ESR and CRP may be raised.

Clotting abnormalities can include a prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time due to the lupus anticoagulant (LA), one of the antiphospholipid antibodies along with anticardiolipin antibody (aCL) and others. Paradoxically, there is an associated predisposition to both venous and arterial blood clots when these are positive.

Serological abnormalities

The antinuclear antibody (ANA) is present in 95% of patients with SLE, but may also occur in other connective tissue and inflammatory diseases, as well as at low levels in healthy adults. The anti-Smith (Sm) and anti-dsDNA (double-stranded DNA) antibodies are more specific but less sensitive for SLE. Anti-Sm is obtained as part of a panel of antibody tests for extractable nuclear antigens (anti-ENA). Serological abnormalities also include decreased levels of complement components C3 and C4.

Other tests are directed towards the organ system involved, for example, midstream urine specimen looking for proteinuria or glomerular haematuria (>70% dysmorphic red blood cells or red-cell casts) and chest X-ray in the patient with serositis.

Assessing SLE disease activity

It is important to determine SLE disease activity in the ED. Useful symptoms of activity include mouth ulcers, alopecia and constitutional symptoms, as well as organ-specific symptoms, such as arthralgia or pleuritic chest pain.

Investigations used to assess disease activity include complement levels (low in active SLE), CRP and ESR (elevated), as well as anti-dsDNA titre. These are not diagnostic and many people with quiescent SLE may also have hypocomplementaemia or elevated anti-dsDNA titres.

A midstream urine for urinary sediment is an essential marker of renal involvement.

Management

Management of SLE is directed by the organ system involved and includes topical therapies for cutaneous lupus and NSAIDs for arthralgias and mild serositis. Most patients with SLE will be on an antimalarial, such as hydroxychloroquine, helpful for skin and musculoskeletal manifestations as well as organ involvement. Many patients will also be on corticosteroids. Those with major organ involvement will also be taking other immunosuppressants, such as methotrexate, cyclophosphamide or azathioprine. Mycophenolate mofetil is frequently now used as an alternative to cyclophosphamide for lupus nephritis.

Lupus nephritis

Early diagnosis of lupus nephritis is essential to prompt management and prevent progression of renal damage. Patients may be asymptomatic or present with nocturia, haematuria or proteinuria. Other presentations include hypertension, rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis and the nephrotic syndrome.

Urinalysis is the most useful investigation in detecting lupus nephritis and proteinuria is the most common abnormality detected. The fresh urine specimen should be sent for phase contrast microscopy in order to detect the presence of dysmorphic erythrocytes (>70% indicates glomerular disease) or cellular casts.

Urinalysis can expedite the investigation and further management of this potentially organ-threatening condition. Prompt referral to a rheumatologist or renal physician for consideration of renal biopsy and further management is indicated.

Neuropsychiatric SLE

There is a myriad of neuropsychiatric manifestations of neuropsychiatric SLE. Neurological presentations include:

Psychiatric presentations include:

These presentations are non-specific and have a broad differential diagnosis or can be subtle and progress. Unfortunately, there is no specific diagnostic test which helps differentiate SLE from other potential aetiologies. Thus, the diagnosis is made from a range of clinical features and tests. The role of the emergency department is first to exclude the more common non-SLE presentations, such as meningitis or intracranial haemorrhage.

Investigations

Imaging studies are needed as well as tests for SLE activity (see above). CT brain scan may detect changes of acute infarction, but is also useful in excluding other non-SLE causes, such as haemorrhage or tumour. MRI is more sensitive in detecting white matter abnormalities, although they are frequently non-specific.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis is essential to exclude infection, but may be normal in SLE. Changes, such as elevated protein, low glucose or even a positive ANA, are non-specific and do not always reflect active SLE. The electroencephalogram is occasionally useful in cases of unexplained altered conscious level with suspected non-convulsive status epilepticus.

Temporal (giant cell) arteritis and other vasculitides

Temporal (giant cell) arteritis

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is the most frequent vasculitis and almost exclusively affects Caucasians. It is a large and medium vessel vasculitis of unknown aetiology, which predominantly affects the cranial branches of arteries originating from the aortic arch and, commonly though not exclusively, the temporal artery.

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is a syndrome of inflammatory pain and stiffness in the shoulder and pelvic girdles that occurs alone or frequently in association with GCA.

Epidemiology

GCA and PMR rarely ever occur before the age of 50 years [8], with a mean age at diagnosis of approximately 72 years. The incidence of GCA is roughly 1 in 500 of people over the age of 50 years, although the incidence and prevalence of PMR are less well studied.

Clinical features

The most common symptom of GCA is new headache, usually localizing to the temporal region, although it can be more diffuse. The area is often tender and worsened by brushing the hair. Most patients complain of constitutional symptoms, such as malaise, fatigue, anorexia and weight loss. Jaw claudication (pain after a period of chewing) is the most specific symptom for GCA, although not sensitive, as it is present in only 34% [8]. On examination, the temporal arteries may be thickened, ‘ropey’ and tender with a reduced or absent pulse.

The most serious complication of GCA is anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (AION) resulting in sudden painless loss of vision which can be bilateral, particularly if untreated. Less commonly, other branches of the aorta may be involved resulting in hemiparesis, arm claudication, aortic dissection or myocardial infarction.

Polymyalgia rheumatica

PMR usually affects the neck, shoulder and pelvic girdles resulting in stiffness and inflammatory pain, worse in the morning and after rest. The pain is often poorly localized and muscle atrophy may occur late in the disease. There may also be synovitis affecting the shoulders, knees, wrists and hands.

The relationship between onset of symptoms of GCA and PMR is highly variable. PMR symptoms may occur before, after or with GCA symptoms. At some point, 5–15% of patients with PMR will have a diagnosis of GCA and about 50% of patients with GCA have symptoms of PMR.

Differential diagnosis of GCA and PMR

GCA can mimic any of the other vasculitides. Non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy can also mimic GCA. The differential diagnosis of PMR includes late-onset RA, polmyositis and other myopathies, fibromyalgia, malignancy and hypothyroidism.

Investigations

The classic non-specific laboratory finding in GCA and/or PMR is a markedly elevated ESR (often>100 mm/h). CRP is also usually elevated and a full blood count often shows a mild normochromic normocytic anaemia.

A temporal artery biopsy confirms the diagnosis of GCA and is particularly useful when the diagnosis is doubtful or the presentation atypical. However, as there is a false negative rate of 10–30%, a negative biopsy does not exclude GCA.

Criteria for diagnosis

The ACR classification criteria for GCA are helpful in differentiating GCA from other forms of vasculitis [9]. They include age at onset>50 years, a new headache, temporal artery tenderness or decreased pulsation and an ESR>50. An abnormal artery biopsy showing vasculitis with mononuclear infiltrate or granulomatous inflammation with multinucleated giant cells also confirms the diagnosis.

Although various classification criteria for PMR have been published, having excluded other diagnoses (except GCA), the presence of all three of the following clinical and laboratory criteria defines the diagnosis [10]:

In practice, rapid response to prednisolone≤20 mg daily is also used as an additional criterion with 50–70% improvement within 72 hours.

Management

Corticosteroids are essential for GCA and should not be withheld to perform a biopsy. The initial dose for GCA is unclear, but prednisone 1 mg/kg/day is used especially for ischaemic complications. However, lower doses, such as prednisone 40–60 mg, are recommended for uncomplicated disease [10].

The dose of prednisone for PMR uncomplicated by GCA is lower at 10–20 mg/day; 15 mg is generally agreed as an appropriate standard dose [11]. Most GCA patients do not require hospital admission, provided a temporal artery biopsy can be organized within a few days. However, patients with visual loss at diagnosis require urgent treatment often with pulsed parenteral corticosteroids and inpatient admission. Patients with GCA should also be commenced on aspirin.

Approach to the other systemic vasculitides

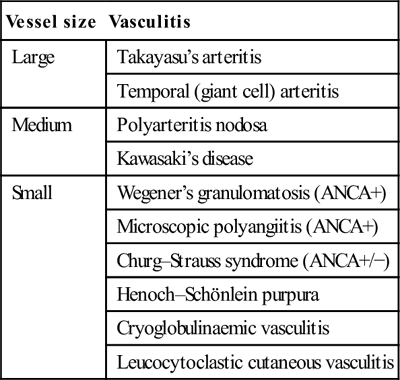

The systemic vasculitides are a group of disorders characterized by an inflammatory infiltrate in the walls of blood vessels resulting in damage to the vessel wall. The clinical manifestations depend upon the size of vessel and location in the vascular tree and may result in systemic or organ-specific manifestations. Table 14.1.2 classifies vasculitic syndromes according to vessel size (there is much overlap).

Table 14.1.2

Classification of systemic vasculitis according to vessel size

| Vessel size | Vasculitis |

| Large | Takayasu’s arteritis |

| Temporal (giant cell) arteritis | |

| Medium | Polyarteritis nodosa |

| Kawasaki’s disease | |

| Small | Wegener’s granulomatosis (ANCA+) |

| Microscopic polyangiitis (ANCA+) | |

| Churg–Strauss syndrome (ANCA+/−) | |

| Henoch–Schönlein purpura | |

| Cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis | |

| Leucocytoclastic cutaneous vasculitis |

Clinical features

An underlying vasculitis should be considered in patients who present with one or more of the following:

unexplained systemic illness – fatigue, fevers, night sweats, malaise

unexplained systemic illness – fatigue, fevers, night sweats, malaise

unexplained ischaemia of an organ or limb

unexplained ischaemia of an organ or limb

chronic inflammatory sinusitis and chronic discharge or bleeding from the nose or ears

chronic inflammatory sinusitis and chronic discharge or bleeding from the nose or ears

microscopic haematuria, especially if dysmorphic glomerular erythrocytes

microscopic haematuria, especially if dysmorphic glomerular erythrocytes

any of the above in the setting of atopy and peripheral blood eosinophilia.

any of the above in the setting of atopy and peripheral blood eosinophilia.

Investigations and diagnosis

Baseline investigations should include full blood count (FBC), urea and electrolytes (U&E), liver function tests (LFTs) and clotting studies as well as CRP and ESR. Blood cultures should be taken if the patient is systemically unwell.

A panel of autoimmune serological tests is carried out including ANA, ENA, rheumatoid factor, dsDNA, anticyclic citrullinated peptides (anti-CCP), complement levels (C3, C4), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) and cryoglobulins. PAN is associated with hepatitis B and cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis with hepatitis C infection.

Collection of a midstream urine specimen to look for glomerular haematuria is mandatory when vasculitis is suspected. Imaging is indicated, such as chest X-ray, CT scan of the chest or sinuses or other areas depending on the suspected organ involved. The definitive diagnosis of vasculitis requires biopsy of affected tissue or angiography.

Differential diagnosis of systemic vasculitis

Other conditions which may mimic systemic vasculitis include:

Management of systemic vasculitis

Treatment is usually with high-dose corticosteroids and, depending on the condition, additional immunosuppression, such as cyclophosphamide. Urgent specialist referral is essential.

Ankylosing spondylitis

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is an inflammatory arthritis of the axial skeleton which can result in progressive spinal fusion. It affects<1% of the general population and its prevalence is linked to the prevalence of HLA-B27.

The hallmark pathological feature of AS is new bone formation and spinal fusion which, combined with the increased prevalence of low bone mineral density in these patients, makes spinal injury a particular risk. Also a range of features including reduced mobility and muscle atrophy lead to a higher falls risk.

Spinal fractures are up to four times more common in AS patients than in the general population and the risk of spinal cord injury is even higher. Fractures can occur at any point in the spine and do not have the classical appearance of wedge or endplate compression. In advanced fusion, the spine may fracture in a similar way to a long bone and not respect traditional spinal anatomical boundaries. There is also a higher rate of atlanto-axial subluxation, with similar precautions required as in those with RA. Furthermore, patients with advanced fusion may also develop cauda equina syndrome in the absence of a fracture.

Fractures in AS can be missed by plain X-ray and the onset of new spinal pain or a change in spinal pain necessitiates further imaging with either CT or MRI.

Rheumatological therapy emergencies

The medications used in rheumatology include NSAIDs, corticosteroids, DMARDs and biological DMARDs. These medications are all associated with adverse effects which occasionally result in serious morbidity.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

NSAIDs are commonly used for relief of arthralgia in both inflammatory and non-inflammatory conditions. They are of equal efficacy, although those with shorter half-lives appear to have less gastrointestinal toxicity [12]. NSAIDs should be used in the lowest possible dose for the shortest duration and combinations of NSAIDs (except aspirin) should be avoided [12].

The most common adverse effects of NSAIDs include peptic ulcer disease and acute renal failure, both related to inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis. Gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity is more common in the elderly, those on anticoagulants and with high doses or prolonged duration of NSAIDs. Prescribe a proton pump inhibitor when there is concern about GI toxicity. The COX-2 selective inhibitors, such as celecoxib, have a reduced incidence of peptic ulcer disease, but a similar incidence of other adverse effects including hypertension, peripheral oedema and cardiac failure. There is an increased risk of cardiovascular deaths with prolonged courses.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment for most inflammatory rheumatological conditions. At high doses, they provide rapid control of inflammatory disease and are often required for long-term management at low doses. Long-term use is associated with numerous adverse effects, such as diabetes, hypertension and osteoporosis. In addition, psychosis and mood disorders related to corticosteroid use, as well as peptic ulcer disease, may present as an emergency.

Although there is concern about infection among patients on DMARDs, prednisolone contributes considerably (possibly more) to the immune-suppressed patient’s overall infection risk.

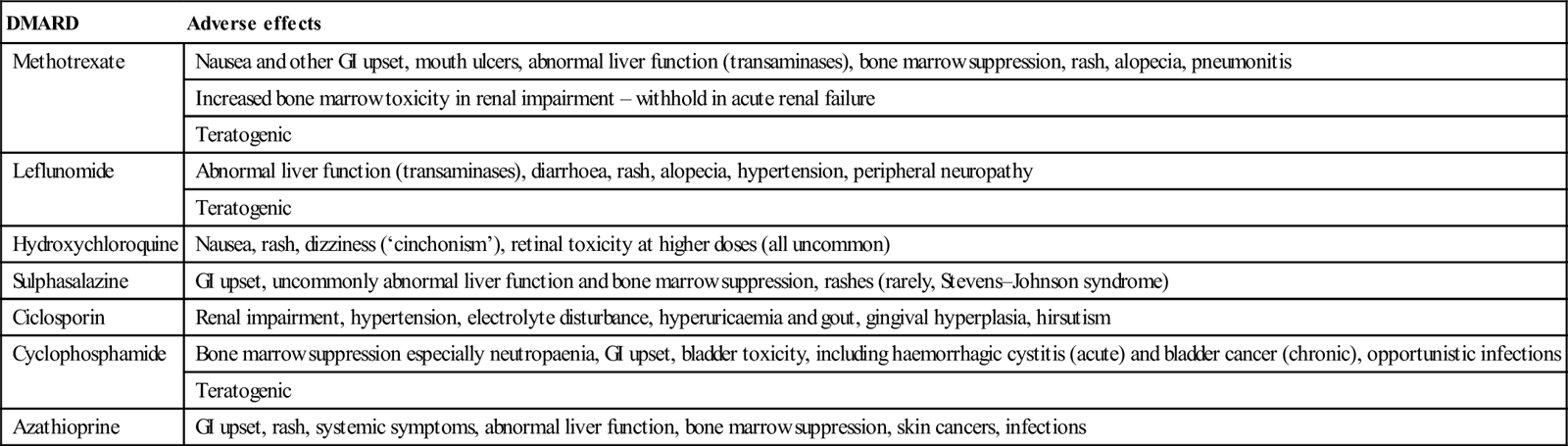

Immunosuppressants/disease modifying antirheumatic drugs

This heterogeneous group of medications is used to prevent joint destruction in the inflammatory arthritides and as steroid-sparing therapy in many connective tissue diseases. They include methotrexate, leflunomide, hydroxychloroquine, sulphasalazine, ciclosporin, azathioprine and cyclophosphamide. Each drug has its own range of adverse effects, but common adverse effects include cytopaenias, rashes including Stevens–Johnson syndrome, abnormal liver function tests, GI toxicity and heightened susceptibility to infections (Table 14.1.3).

Table 14.1.3

Adverse effects of disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

| DMARD | Adverse effects |

| Methotrexate | Nausea and other GI upset, mouth ulcers, abnormal liver function (transaminases), bone marrow suppression, rash, alopecia, pneumonitis |

| Increased bone marrow toxicity in renal impairment – withhold in acute renal failure | |

| Teratogenic | |

| Leflunomide | Abnormal liver function (transaminases), diarrhoea, rash, alopecia, hypertension, peripheral neuropathy |

| Teratogenic | |

| Hydroxychloroquine | Nausea, rash, dizziness (‘cinchonism’), retinal toxicity at higher doses (all uncommon) |

| Sulphasalazine | GI upset, uncommonly abnormal liver function and bone marrow suppression, rashes (rarely, Stevens–Johnson syndrome) |

| Ciclosporin | Renal impairment, hypertension, electrolyte disturbance, hyperuricaemia and gout, gingival hyperplasia, hirsutism |

| Cyclophosphamide | Bone marrow suppression especially neutropaenia, GI upset, bladder toxicity, including haemorrhagic cystitis (acute) and bladder cancer (chronic), opportunistic infections |

| Teratogenic | |

| Azathioprine | GI upset, rash, systemic symptoms, abnormal liver function, bone marrow suppression, skin cancers, infections |

Biological disease modifying antirheumatic drugs

The so-called ‘biological’ DMARDs are a newer and expanding collection of therapies directed against molecules and cells that mediate joint destruction and help drive the inflammatory process. These therapies are being increasingly used for those who fail conventional DMARD therapy for RA and TNF inhibitors are also used for treatment-resistant psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, as well as other non-rheumatological conditions.

Adverse effects associated with biological DMARDs include an increased risk of infections, particularly soft-tissue and joint infections, as well as reactivation of tuberculosis. Other opportunistic infections appear more common, such as listeriosis. Patients may also develop local injection site reactions and infusion-related reactions, which can be delayed. Less common adverse effects include a form of drug-induced lupus and demyelination.

Presentations of treatment-related emergencies

Infections

As treatment of rheumatological conditions is directed at immunosuppression, infections are a common and expected adverse effect of therapy. Although studies have shown RA patients to have a de novo increased risk of infection, biological DMARDs further increase this risk. Although most of the larger studies have focused on TNF inhibitors, which have been available the longest, there is an increased risk of serious infections compared to the general RA population. This risk may be highest in the first 6 months of therapy [13].

Patients on biological therapy who develop an infection are advised temporarily to cease their treatment and to commence antibiotics. If in doubt, they should be admitted to hospital to receive parenteral antibiotics. There is also an increased risk of reactivation of tuberculosis and infections such as Listeria and Salmonella[13]. Rigorous tuberculosis screening prior to commencement of anti-TNF therapy should now be universal.

Special mention must be made of the biological agent tocilizumab directed against interleukin-6. Tocilizumab causes marked suppression of acute phase reactants, particularly CRP and, even in the presence of active infection, a patient on this may have a normal CRP. Thus if there is a clinical suspicion of infection, appropriate antibiotic therapy must be instituted regardless.

Bone marrow suppression

Anaemia, leucopaenia and thrombocytopaenia all may occur in patients taking DMARDs, such as methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, sulphasalazine and azathioprine, with neutropaenic sepsis a particular danger.

Cytopaenia in a patient taking methotrexate is uncommon but those at increased risk include the elderly and those with renal impairment, related to the drug’s mechanism of action as an inhibitor of dihydrofolate reductase. Management includes temporary cessation of treatment and administration of folinic acid, the active form of folic acid which does not require to be converted by dihydrofolate reductase.

The most common adverse effect of cyclophosphamide is myelosuppression, particularly leucopaenia. The white cell nadir occurs at 2 weeks post-infusion following intravenous therapy. Patients on oral therapy may experience a gradual decrease in white cell count, which is typically less predictable than on intravenous therapy.

Bone marrow suppression may also occur as a side effect of azathioprine treatment, especially if given in combination with allopurinol which inhibits its metabolism, thus potentiating bone marrow toxicity. Cytopaenias are also more common in patients with deficient thiopurine methyltransferase enzyme. Sulphasalazine therapy is uncommonly complicated by bone marrow suppression.

DMARD-related pneumonitis

Methotrexate and leflunomide may both result in lung toxicity. The incidence of methotrexate-induced lung toxicity is difficult to assess but uncommon, with those patients at higher risk who have prolonged duration of methotrexate treatment, pre-existing rheumatoid involvement of the lungs and pleura, increased extra-articular manifestations, diabetes mellitus, previous DMARD use and a low serum albumin [14]. Age and smoking also appear to be important. The most frequent is a hypersensitivity pneumonitis, but other forms of lung injury may occur both acute and chronic, with rapid progress to respiratory failure in more acute situations. Clinical features are non-specific and include constitutional symptoms, cough and progressive dyspnoea. Subacute presentations are more common.

Imaging reveals interstitial opacities and patchy consolidation. High-resolution CT scanning typically shows a ground-glass appearance. The main differential diagnosis is of a respiratory infection which may be due to typical pathogens or opportunistic infections, such as Pneumocystis jirovecii.

Management is supportive with empiric antibiotic therapy in case of infection. Corticosteroids are also used. Patients may become seriously ill and require intensive care, but mortality is still low (1%).

Leflunomide may also cause lung injury, typically in the first few months of therapy and usually when given in combination with methotrexate.

Allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome

Minor hypersensitivity reactions to allopurinol occur in about 2% of patients and usually consist of a mild rash. Rarely, a severe hypersensitivity syndrome may present in an unwell patient with fever, rash including toxic epidermal necrolysis, erythema multiforme or a diffuse macropapular or exfoliative dermatitis, abnormalities of liver function, peripheral blood eosinophilia and acute renal failure due to interstitial nephritis. It is more common in those with renal impairment who do not have an appropriate dose reduction. This presentation has a mortality rate of 25%. Treatment is supportive.

14.2 Monoarthritis

Michael J Gingold, Adam B Bystrzycki and Flavia M Cicuttini

Septic arthritis

The assessment of a patient with acute monoarthritis is focused on excluding a septic arthritis. Septic arthritis can cause rapid joint destruction and mortality has been reported as high as up to 15% [1].

Pathogenesis and pathology

Non-gonococcal bacterial arthritis occurs when bacteria enter the synovial lining of a joint via the haematogenous route, local spread from nearby soft-tissue infections or following penetrating trauma or injury to a joint.

When the bacteria reach the synovium, they trigger an inflammatory response and bacteria and inflammatory cells enter the synovial fluid in the joint space, causing swelling and destruction of articular cartilage. These destructive changes may extend to subchondral bone and produce irreversible damage within days. The commonest causative organisms are staphylococci and streptococci.

Epidemiology and risk factors

The prevalence of septic arthritis ranges between 4 and 10:100,000 patients per year and appears to be rising. It is also almost seven times more common in indigenous Australians [2].

Risk factors for septic arthritis include inflammatory arthritis (especially rheumatoid arthritis), diabetes mellitus and systemic factors, such as age greater than 80 years, as well as local factors, such as recent joint surgery, joint prosthesis and overlying skin infection. These individual risk factors increase the risk of septic arthritis by two- to threefold [3]. Skin infection overlying a prosthetic joint increases the risk of infection by 15-fold [3].

Clinical features

Septic arthritis presents with joint pain and swelling in over 80% of cases, which may or may not be associated with systemic symptoms, such as sweats and rigors [3]. The hip and knee joints are the most commonly involved joints.

The patient may be febrile and the affected joint is usually swollen, warm, erythematous and tender. Classically, there is reduced ability to actively move the joint and marked pain on passive movement. Unfortunately, the symptoms and signs are not sensitive and a patient with septic arthritis may present with only certain of these features. Thus, septic arthritis cannot be excluded with confidence on the history and examination alone.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of acute monoarthritis is shown in Table 14.2.1. Ask the patient about a history of previous rheumatological disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis, gout or other inflammatory arthritis, as well as risk factors for infection, such as immunosuppression, including diabetes and steroids. Recent trauma or history of a bleeding diathesis or anticoagulation are also relevant. Finally, ask the patient about any recent sexually transmitted infection, including gonococcal infection or non-specific urethritis, or any systemic features including uveitis and/or gastrointestinal infection, which may point towards a reactive arthritis.

Table 14.2.1

Common presentations with acute monoarthritis to an emergency department

Gout

Reactive arthritis such as post-viral, Reiter’s syndrome

Acute exacerbation of pre-existing inflammatory arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Septic arthritis

Note: Orthopaedic-related joint problems, such as trauma and/or haemarthrosis, plus osteoarthritis (OA) were not included in this series [4].

Clinical investigations

Blood tests

Send blood for a full blood count, which may reveal an elevated peripheral white blood cell count, as well as C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). ESR and CRP are non-specific and not sensitive for septic arthritis, but may help in the differential diagnosis. Blood cultures are taken in the presence of fever. Finally, a serum urate may be elevated, but can be normal in acute gout.

Imaging

X-ray may be normal in septic arthritis, as it takes at least one week for destructive changes to appear on plain X-ray. Magnetic resonance imaging when available, while non-specific, is frequently helpful to determine if the pathology is in the joint or juxta-articular bone.

Joint aspiration

The single most important investigation is synovial fluid aspiration and analysis. Send the aspirate in a sterile container for Gram stain and culture, as well as for polarizing light microscopy to look for the presence of urate (strongly negative birefringent) crystals or calcium pyrophosphate crystals (weakly positive birefringent crystals). Using blood culture bottles does not appear to increase the yield of a positive culture.

Place some of the aspirate in an EDTA tube for a white cell count to be performed. The likelihood of septic arthritis increases from 2.9% with a synovial white cell count above 25,000/μL up to 28% with a synovial white cell count of greater than 100,000/μL. Synovial glucose and protein levels are unhelpful.

Criteria for diagnosis of septic arthritis

There is no ‘gold standard’ test for the diagnosis of septic arthritis. Synovial fluid Gram stain has a sensitivity of up to 50% only, while culture has a sensitivity up to 85% [3]. However, combined with an appropriate clinical presentation, the presence of microorganisms in synovial fluid on Gram stain and/or a positive synovial fluid culture with high synovial white cell count are diagnostic.

Treatment

Treatment of septic arthritis requires parenteral antibiotics and urgent referral to orthopaedics for surgical drainage with admission to hospital. Commence empirical antibiotic therapy with dicloxacillin or flucloxacillin 2 g IV 6-hourly or cephalothin 2 g IV 6-hourly (or cephazolin) if patient is allergic to penicillin to cover against Staphylococcus, until guided by microbiology results.

The patient with suspected hip sepsis or sepsis affecting a prosthetic joint must be referred to orthopaedics urgently without attempting joint aspiration.

Gout

Gout is an intra-articular inflammatory response to monosodium urate crystal deposition usually related to hyperuricaemia. It is more common in males than females, but is extremely rare in the premenopausal female.

Aetiology and pathogenesis

Uric acid is derived from purine metabolism. Hyperuricaemia is the strongest predictor for gout and relates to either overproduction or underexcretion of uric acid. Hyperuricaemia may also cause radiolucent renal calculi.

Overproduction of uric acid is due to dietary factors, such as beer, fructose-containing soft drinks, shellfish and other purine-rich foods, or endogenous factors associated with high cell turnover, such as a haematological malignancy. Reduced excretion is related to chronic kidney disease, hypovolaemia, acidosis and medications, such as diuretics, ciclosporin, pyrazinamide, ethambutol and low-dose aspirin. There is frequently a family history of gout.

Epidemiology

The peak incidence of acute gout occurs in men between the ages of 30 and 60 years and in women between 55 and 70 years. The presentation of gout in younger patients should prompt a search for a secondary cause (including lifestyle factors). Gout is more common in Maori and Polynesian populations.

Clinical features

The classic presentation is of acute onset of a hot, swollen and painful first metatarsophalangeal joint (75% of cases) known as podagra. Other commonly affected joints include joints in the foot, the ankle, knee and small joints of the hand.

Common triggers of an acute attack are binges of alcohol or purine-rich foods, dehydration, severe illness such as sepsis, trauma and surgery. Sudden cessation or the introduction (especially in an acute attack) of hypouricaemic agents, such as allopurinol or probenecid, may also precipitate gouty arthritis, as can the introduction or a dose change of a diuretic.

Untreated, the symptoms will abate over the course of several days to 2 weeks. Occasionally, the patient may appear systemically unwell during an acute attack with malaise and systemic inflammatory response features. Examination reveals a tender, warm and erythematous joint with severely restricted range of movement. The patient may also be febrile. Presentations of acute gout may also be polyarticular (see Chapter 14.3).

Recurrent untreated acute gout and hyperuricaemia results in chronic tophaceous gout, where the patient is no longer pain-free between attacks. Examination reveals tophus formation on the ears, around the elbows and in the fingers with marked joint deformity.

Investigations and diagnosis

Synovial fluid aspiration

Synovial fluid aspirate to identify monosodium urate crystals is diagnostic of acute gout. The crystals may be phagocytosed (intracellular) and the synovial fluid will have a high white cell count. Send fluid for Gram stain and culture to rule out septic arthritis, which may rarely coexist with gout. Podagra with a typical clinical scenario has a sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 95% for acute gout, so aspiration is not indicated [5].

Blood tests

Hyperuricaemia on blood testing is not diagnostic of gout as, although up to 5% of adults may have a raised serum uric acid at some point, only one-fifth (1% overall) will ever have an attack of gout. Conversely, in about one-third of patients with gout, the serum uric acid level is normal during an acute attack. Other blood tests, such as FBE, ESR and CRP are sent and may be abnormally elevated. Check the renal function with serum urea and creatinine both to identify a potential aetiology and help guide treatment, such as avoidance or reduced doses of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or colchicine.

Imaging

Plain X-ray is performed to exclude injury, but should be normal in the acute attack other than soft-tissue swelling. Punched-out periarticular erosions are seen in chronic gouty arthritis which, when associated with calcium deposition, deforming arthritis and soft-tissue swelling, are characteristic of chronic tophaceous gout.

Management

The aim is to treat acute pain and then prevent chronic relapse with hypouricaemic drugs. Colchicine is losing favour due to the frequency of its side effects and potential for serious toxicity. Educate all patients to correct lifestyle factors where appropriate.

Acute attack

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

After excluding infection, give either an NSAID, corticosteroid and/or colchicine in the absence of contraindications. Give diclofenac 50 mg tds orally followed by 25 mg tds orally or naproxen 500 mg followed by 250 mg tds orally until symptoms subside. A selective COX-2 inhibitor, such as celecoxib 100 mg bd orally, is preferred in patients with a history of peptic ulcer disease, although there is a similar risk of renal dysfunction in the elderly or with pre-existing renal disease.

Corticosteroids

Patients with gout refractory to the above treatment or in whom other treatment is contraindicated may be given corticosteroids, such as prednisolone 25–50 mg daily for 3 days, then weaned over 1–2 weeks [6,7]. An alternative approach is intra-articular corticosteroid for monoarticular gout provided sepsis has been excluded.

Colchicine

When NSAIDs and prednisone are contraindicated, colchicine may be used. Doses of 0.5 mg 6- or 8-hourly orally have equivalent efficacy and a lower rate of gastrointestinal toxicity compared to higher doses [8]. Higher doses, such as colchicine 1.0 mg followed by 0.5 mg up to four times daily, with a maximum cumulative dose of 6–8 mg per acute attack are no longer recommended, due to increased toxicity with nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and the risk of renal impairment. All colchicine doses should thus be less with renal impairment, as these patients are at risk of severe neuromyopathy and/or who are on statins, as this combination may increase the risk of myopathy and rhabdomyolysis.

Recurrent attacks

Urate lowering therapy

A second attack of gout usually requires urate lowering therapy, although this is not usually commenced in the emergency setting, as treatment should be delayed until the acute flare up has settled. Allopurinol, a xanthine oxidase inhibitor, prevents the production of uric acid from xanthine. It is introduced at a low dose once the acute attack has settled and gradually titrated up to a maximum of 300 mg daily [9]. Typically, the patient will remain on a low-dose NSAID (or prednisolone/low-dose colchicine) as prophylaxis against precipitating further acute attacks.

Febuxostat is a new orally administered selective xanthine oxidase inhibitor for gout that may be used to reduce urate levels, particularly in patients with poor kidney function or intolerant of allopurinol, such as due to a hypersensitivity reaction.

An alternative uricosuric agent to allopurinol is probenecid, which should be avoided in renal impairment.

Acute pseudogout

Acute pseudogout causes an acute monoarthritis and is one of the several potential presentations of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) deposition disease. It is more common in females and patients over 65 years old.

Aetiology and pathogenesis

Calcium pyrophosphate disease is characterized by deposition of CPPD crystals in cartilage causing chondrocalcinosis. When released, there may be uptake in other synovial structures and an inflammatory response producing acute synovitis, tenosynovitis or bursitis.

Advanced age is the strongest risk factor. Other associations are a family history, metabolic diseases such as haemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease, hyperparathyroidism, hypophosphataemia or hypomagnesaemia and mechanical factors, such as previous injury or osteoarthritis (OA).

Clinical features

CPPD deposition disease presents in a variety of ways. The two most common are acute pseudogout and chronic pyrophosphate arthropathy, which may mimic OA. Other presentations include tenosynovitis, bursitis or as an incidental radiographic finding of chondrocalcinosis. CPPD deposition disease may also mimic rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis, as well as the neuropathic joint.

Acute pseudogout typically presents in older patients and the knee is the most commonly affected joint. Other common sites include the wrist, shoulder, elbow and ankle. Occasionally, there may be an oligoarticular presentation. Presentation is with a hot, red and swollen joint. There may be systemic inflammatory response features and the patient may be febrile. Triggers include trauma, surgery or illness, but most cases are spontaneous.

Investigations and clinical diagnosis

Joint aspiration

Diagnosis of pseudogout depends on the demonstration of CPPD crystals in synovial fluid, which is frequently blood stained. Polarizing light microscopy demonstrates weakly positive birefringent rhomboid-shaped crystals.

Laboratory studies and imaging

Younger patients presenting with polyarticular chondrocalcinosis should be screened for an underlying metabolic cause, checking serum calcium, magnesium, phosphate, alkaline phosphatase, parathyroid hormone, thyroid function and iron studies.

Plain X-rays of the joint may reveal chondrocalcinosis seen in fibrocartilage, such as the knee menisci, triangular cartilage of the wrist and pubic symphysis. Other characteristic findings are of marked degenerative change in joints that are not usually affected by OA.

Management

Symptoms of acute pseudogout frequently improve once the joint has been aspirated. Intra-articular injection of corticosteroid is also appropriate for acute monoarthritis, once infection has been excluded. In addition, rest and splintage for 48–72 h is beneficial.

Give oral analgesics and NSAIDs similar to acute gout, particularly for polyarticular pseudogout as performing multiple joint injections is impractical and painful.

Take care using NSAIDs in the elderly and use the smallest doses to avoid renal impairment and precipitating heart failure.

Haemarthrosis

Haemarthrosis is bleeding into a joint which may be traumatic and related to intra-articular injury or non-traumatic related to an underlying bleeding diathesis.

Aetiology

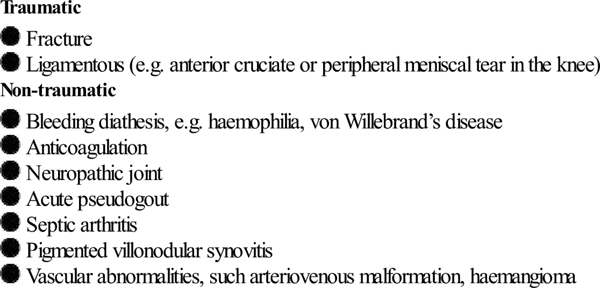

The causes of haemarthrosis are listed in Table 14.2.2.

Clinical features

A haemarthrosis causes a painful swollen joint with a reduced range of movement. The joint is often warm. Ask about a history of trauma and, if minimal or absent, consider a bleeding disorder, such as haemophilia or anticoagulant use. Also ask about troublesome bleeding during a previous operation or following dental instrumentation and about a family history.

Investigations

Perform plain radiography to exclude a fracture. Consider a computed tomography scan if there is a high index of clinical suspicion but normal plain imaging. Send a full blood count and a coagulation screen if there is no history of significant trauma.

Haemarthrosis is diagnosed on aspiration of synovial fluid. An intra-articular fracture is indicated by observing fat globules floating on the surface of the blood.

Management

Management includes rest, immobilization, ice and compression as well as analgesia. Aspiration frequently provides pain relief if performed within 24 h of onset. NSAIDs should be avoided in patients with a bleeding diathesis.

Haemophilia or other bleeding diathesis

Haemarthrosis due to haemophilia or other disorders of clotting factor deficiency requires immediate factor replacement therapy to a level of 40–50% of normal. This should be performed as soon as possible after the presentation, in consultation with a haematology specialist.

Often the patient will be able to advise on their normal treatment (and usually knows what factor they are deficient in, their usual basal level and how much replacement is necessary in an acute bleed).

Vitamin K and administration of fresh frozen plasma may be required in patients with elevated INR related to warfarin toxicity.

Spondyloarthritis

Monoarthritis is occasionally a presentation of a spondyloarthritis, such as reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease-associated arthritis.

Clinical features suggesting a reactive arthritis include a recent history of infective diarrhoea, uveitis or sexually transmitted infection, such as urethritis. The patient may appear ill and be febrile with a tachycardia. The patient should be asked about a history of psoriasis or inflammatory bowel disease in the past.

Check for sites of enthesitis with inflammation at a tendon insertion points, such as the Achilles tendon or plantar fascia around the heel, or dactylitis causing ‘sausage-shaped’ digits.

Guideline approach to the management of acute monoarthritis

The British Society for Rheumatology, in conjunction with other medical associations, published guidelines in 2006 regarding an approach to the hot swollen joint. No changes were recommended on review in 2012 [10]. These guidelines are summarized below:

Other investigations should include blood cultures, CRP, ESR and full blood count.

Other investigations should include blood cultures, CRP, ESR and full blood count.

X-ray of the affected joint should be performed as a baseline.

X-ray of the affected joint should be performed as a baseline.

Septic joints require aspiration to dryness in addition to parenteral antibiotics.

Septic joints require aspiration to dryness in addition to parenteral antibiotics.

Prosthetic joints and suspected hip sepsis require an urgent orthopaedic opinion.

Prosthetic joints and suspected hip sepsis require an urgent orthopaedic opinion.

14.3 Polyarthritis

Shom Bhattacharjee, Adam B Bystrzycki and Flavia M Cicuttini

Introduction

Polyarthritis is a frequent rheumatological presentation to the emergency department in adults. This chapter focuses on the initial assessment, management and most appropriate follow up of the more common conditions encountered. These include rheumatoid arthritis (RA), seronegative spondyloarthritis including psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis with reference to arthritides occurring in association with enteric and urogenital infections, and infectious arthritis including viral arthritis and rheumatic fever. Management principles include establishing the diagnosis, treating the acute problem and arranging appropriate follow up.

Acute polyarthritis

Polyarthritis syndromes may be difficult to diagnose accurately due to the wide range of differential diagnoses, as seen in Table 14.3.1[1]. Important principles are to rule out infection, quantify underlying inflammation and document extra-articular involvement.

Table 14.3.1

Differential diagnosis of polyarthritis syndromes

Inflammatory

Rheumatoid arthritis

Inflammatory osteoarthritis

Systemic connective tissue disease, including SLE, vasculitis, Behçet’s disease, relapsing polychondritis

Seronegative spondyloarthropathies, commonly psoriatic arthropathy

Gout

Pseudogout (calcium pyrophosphate arthropathy)

Drug induced, including lupus syndromes

Infectious arthritis – bacterial including mycobacteria, endocarditis, protozoal, viral

Reactive or post-infectious arthritis including rheumatic fever

Non-inflammatory

Neoplastic/paraneoplastic disease, including hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy

Sarcoidosis

Endocrine disease, such as haemochromatosis, acromegaly

Haematological disease, such as haemophilia, leukaemia

Clinical features and diagnosis

History

Mode of onset

Distribution

Course

Constitutional symptoms

Rheumatological systems review

Extra-articular organ involvement

Other history

History of recent sore throat, febrile illness, new sexual contact, features of a sexually transmitted disease, diarrhoea, rash or uveitis.

Past medical history of gout, rheumatic fever, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), malignancy and juvenile polyarthritis.

Family history of gout, psoriasis, IBD, uveitis or chronic back pain suggesting ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and other seronegative arthritis.

Examination

Perform a detailed physical examination [4] and document:

Investigations

Laboratory studies

Send blood for full blood count (FBC), urea, electrolytes and liver function tests (ELFTs) and inflammatory markers including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) [1,2].

Send serum antibody or antigen tests as indicated by the history for infectious exposure, such as hepatitis B serology, streptococcal antigen test (ASO titre) and an autoantibody panel including antinuclear antibody (ANA), rheumatoid factor (RF) and antibodies against citrullinated peptides (ACPA) usually ordered as anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP). Antibody tests in particular should be interpreted with caution and in the context of each individual patient, due to their varying sensitivity and specificity [5].

Joint aspiration

Joint aspiration and analysis of synovial fluid are essential to diagnose septic arthritis and crystal arthropathy (see Chapter 14.2).

Imaging studies

Imaging studies, such as plain X-rays, may demonstrate diagnostic features in erosive arthropathy, but these do not occur for some time after the acute onset.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic inflammatory disorder of unknown aetiology characterized by symmetric synovitis, erosive polyarthritis and numerous extra-articular manifestations. It occurs in up to 2% of the general population and is two to three times more common in women [6]. The onset is often indolent and may lack the characteristic symmetrical joint involvement. Uncommonly, it presents as an acute monoarthritis.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis in adults is guided by the American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism critera. These criteria were revised in 2010 [7] to identify features predictive of erosive disease earlier in the illness, compared with the 1987 criteria which defined the disease by its later stage features. Constitutional features, such as malaise and fatigue, are common.

‘Definite RA’ is based on the confirmed presence of:

synovitis in at least one joint

synovitis in at least one joint

absence of an alternative diagnosis that better explains the synovitis

absence of an alternative diagnosis that better explains the synovitis

a total score of 6 or greater (of a possible 10) from individual scores in four domains: number and site of involved joints (score range 0–5); serologic abnormality (score range 0–3); elevated acute-phase response (score range 0–1) and symptom duration (2 levels; range 0–1) (Table 14.3.2).

a total score of 6 or greater (of a possible 10) from individual scores in four domains: number and site of involved joints (score range 0–5); serologic abnormality (score range 0–3); elevated acute-phase response (score range 0–1) and symptom duration (2 levels; range 0–1) (Table 14.3.2).

Table 14.3.2

Classification criteria for RA

A. Joint involvement

1 large joint – 0 pts

2–10 large joints – 1 pt

1–3 small joints (with or without involvement of large joints) – 2 pts

4–10 small joints (with or without involvement of large joints) – 3 pts

>10 joints (at least 1 small joint) – 5 pts

B. Serology (at least 1 test result is needed for classification)

Negative RF and negative ACPA – 0 pts

Low-positive (<3×ULN) RF or low-positive ACPA – 2 pts

High-positive (≥3×ULN) RF or high-positive ACPA – 3 pts

C. Acute-phase reactants (at least 1 test result is needed for classification)

Normal CRP and normal ESR – 0 pts

Abnormal CRP or abnormal ESR – 1 pt

D. Duration of symptoms

<6 weeks – 0 pts

≥6 weeks – 1 pt

Add score of categories A–D: a score of>6/10 classifies a patient as having definite RA

Adapted from [7]

Morning stiffness, symmetric involvement and radiographic erosions are no longer included.

Clinical features

Characteristic presentations in RA include the following [8–10].

Cervical spine

Cervical arthritis is common and may result in critical spinal problems from degeneration of the transverse ligament of the C1 vertebra that produces C1–2 instability in up to 5% of patients and can result in cervical cord compression or vertebral artery insufficiency. In addition, decreased motion and myelopathy may result from longstanding joint involvement.

Upper limb

The wrist, metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints are typically affected, with sparing of the distal interphalangeal joints. Swan-necking and boutonnière deformities are common, together with ulnar deviation at the metacarpophalangeal joints. Fixed flexion deformities may result in entrapment neuropathies, in particular, carpal tunnel syndrome with median nerve involvement. Tenosynovitis may lead to tendon rupture, particularly of the extensor pollicis longus, or degenerative changes in the long extensors of the middle, ring and the little fingers with rupture of these tendons.

Lower limb

The hip and knee are frequently involved. Metatarsophalangeal joint subluxation may occur. Talonavicular joint inflammation causes pronation and eversion deformity, with overlying muscle spasm. A Baker’s cyst due to posterior herniation of the joint capsule of the knee joint may occur and require differentiation from a deep vein thrombosis by Doppler ultrasound. Entrapment of the posterior tibial nerve causes burning paraesthesiae on the sole of the foot.

Extra-articular manifestations

The extra-articular manifestations of RA are protean and may involve any organ system due to local inflammation causing functional or neurological deficits, rheumatoid vasculitis or distant inflammation (see Chapter 14.1). Patients may also present with the side effects of the treatment, including sepsis related to immunosuppression. Sepsis with encapsulated organisms is of particular concern in patients with Felty’s syndrome of RA with splenomegaly and neutropaenia [11].

Investigations

Laboratory studies

Send blood for FBC and ELFTs and non-specific markers of inflammation, such as ESR, and CRP, with assays for serum rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP [12]. Anti-CCP is as sensitive but more specific than rheumatoid factor for RA and is more frequently positive early in the disease process. It is also thought to identify individuals at higher risk of erosive disease [13]. Send blood cultures as well as midstream urine for suspected sepsis.

Joint aspiration

Joint aspiration is essential to exclude coexistent or primary sepsis in any sudden hot, swollen joint.

Imaging

Initial plain imaging of affected joints at first presentation does not usually demonstrate erosive changes, but is useful in patients with longstanding disease. However, always request X-rays of the cervical spine in any patient with cervical or neurological features to look for an atlanto-dens interval of greater than 2.5 mm, which is diagnostic of instability [14]. Include a chest X-ray if there is a fever and/or any respiratory features. Request an ultrasound examination to differentiate deep vein thrombosis from a Baker’s cyst.

Emergency management

Emergency therapy aims to relieve acute pain and reduce joint inflammation. Longer-term goals include restoration and maintenance of joint function and the prevention of periarticular bony and cartilage destruction. Important principles include medication, education, rest and exercise, with the input of a multidisciplinary allied health team incorporating occupational therapy and physiotherapy.

Medication falls broadly under the categories of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) therapy. Readers are referred to Chapter 14.1 for a brief overview of these medications and common adverse effects, as well as the references at the end of this chapter [15–18].

Other long-term measures include orthopaedic and orthotic intervention. Surgery involving joint fusion, synovectomy, total joint arthroplasty and reconstruction may be required.

Early consultation with a rheumatologist is essential, particularly for patients with acute or first presentations. Exclusion of infection even for mild or moderate features is imperative and to control symptoms with simple analgesics with discharge for specialist follow up. Admit patients if there is evidence of multisystem involvement, severe symptoms requiring nursing or allied health management or if they are unable to tolerate oral therapy.

Prognosis

The spontaneous remission rate in RA is less than 10% [19,20]. High titres of anti-CCP or rheumatoid factor, which are present in up to 75% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, the presence of nodules and human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-DR4 haplotype are markers of severity. A patient’s life expectancy is shortened by 10–15 years by accelerated cardiovascular disease, infection, pulmonary and renal disease and gastrointestinal bleeding.

Seronegative arthritis

The seronegative spondyloarthritis disorders are characterized by inflammation of the axial spine with sacroiliitis and spondylitis in particular, enthesitis, which is inflammation at the attachments of tendons and ligaments to bones, dactylitis, asymmetric polyarthritis often of the lower limb, eye inflammation and varied mucocutaneous features [21]. They are labelled ‘seronegative’ as the serum rheumatoid factor is negative.

Epidemiology

The term ‘seronegative spondyloarthritis’ covers conditions such as ankylosing spondylitis (AS), reactive arthritis occurring in the setting of viral or bacterial infection, psoriatic arthritis and arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It is further differentiated into axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis.

The prevalence of the seronegative spondyloarthritis disorders varies widely and may parallel the prevalence of the HLA-B27 gene.

However, the exact role of HLA-B27 in the pathogenesis of these disorders has not been clearly defined. The proportion of HLA-B27 positive individuals who develop symptomatic arthropathy varies widely from 16% in patients with AS to 70% of patients with spondylitis in the setting of IBD [22]. HLA-B27 positive individuals may be less efficient at the intracellular removal of certain inciting bacteria, although this is controversial [23].

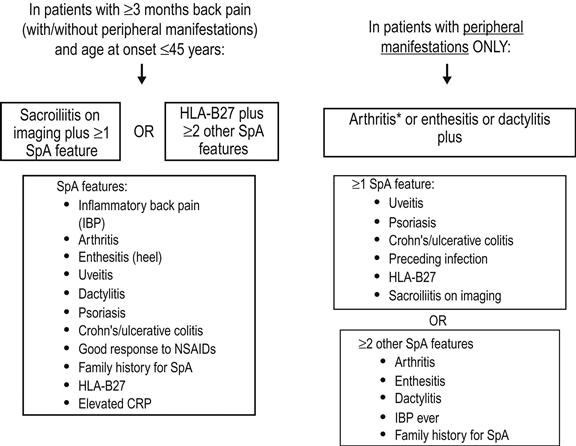

The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) recently advanced classification criteria for axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis (Fig. 14.3.1). These criteria have better sensitivity and comparable specificity to previous criteria and are well validated [24].

Psoriatic arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis is a heterogeneous disease distinct from other inflammatory arthritides. It occurs in 10% of patients with psoriasis, but may affect up to 40% of hospitalized psoriasis patients with widespread skin involvement [25]. It occurs between the ages of 30 and 60 years, with an equal prevalence in males and females. It is thought to be inherited in a polygenic pattern significantly influenced by environmental factors, including trauma and infectious agents. Multiple studies have confirmed the important role of class I HLA, particularly B13, B16 and B27 and certain C-subclasses [26,27]. The arthropathy pattern may be pauci-articular, but more than five peripheral joints are usually involved.

Clinical features and diagnosis

The diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis is essentially clinical, requiring the demonstration of coexisting synovitis and psoriasis. A set of simple clinical diagnostic criteria, the ClASsification criteria for Psoriatic ARthritis (abbreviated to the CASPAR criteria) were proposed by a large international study group in 2006 [28].

CASPAR diagnostic criteria for psoriatic arthritis

Established inflammatory joint disease and at least three points from the following features:

history of psoriasis (in the absence of current psoriasis) (1 point)

history of psoriasis (in the absence of current psoriasis) (1 point)

family history of psoriasis (in the absence of current or past history) (1 point)

family history of psoriasis (in the absence of current or past history) (1 point)

juxta-articular new bone formation (1 point)

juxta-articular new bone formation (1 point)

Five clinical subtypes are recognized, including asymmetric oligoarthritis, symmetric small joint polyarthritis, predominant distal interphalangeal joint involvement, psoriatic spondyloarthropathy and arthritis mutilans [29]. Major extra-articular organ manifestations, such as aortic insufficiency and pulmonary fibrosis, occur rarely. However, up to 30% of patients have mild inflammation at the eye, most commonly conjunctivitis.

Asymmetric oligoarthritis

This occurs in 30–50% of patients [30]. It presents as an oligoarthritis involving a single large joint, in association with a ‘sausage-shaped’ or dactylitic digit or toe. Dactylitis occurs due to a combination of arthritis and tenosynovitis. Distal interphalangeal joint involvement is typical, almost invariably associated with psoriatic nail changes of pitting, ridging and onycholysis. Enthesitis occurs most frequently with this form of the disease and commonly manifests as plantar fasciitis or epicondylitis at the elbow.

Symmetric small joint polyarthritis

This occurs in 30% of patients, in a pattern strongly resembling RA, but with more frequent distal interphalangeal joint involvement [30].

Psoriatic spondyloarthritis

This occurs in 5% of patients [30]. It is often asymptomatic, but may present with inflammatory low back pain due to sacroiliitis in up to 30% of cases.

Arthritis mutilans

‘Arthritis mutilans’ is a rare (<5% of patients), but well-characterized feature of psoriatic arthritis with severely deforming arthritis including telescoping of the fingers or toes from osteolysis of the metacarpal or metatarsal bones and phalanges [30].

Dermatological features

Dermatological features include typical erythematous, scaling plaques on the extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, scalp and ears and nail changes. The nail changes include pitting with usually greater than 20 pits, ridging with transverse depressions and onycholysis with separation of the nail from the underlying nail bed [25]. Nodules and vasculitic features such as digital ulcers are not seen.

Psoriatic arthritis can be difficult to distinguish from the other seronegative spondyloarthritides in the absence of dermatological features or a positive family history.

Investigations

ESR and CRP are raised, but the rheumatoid factor and autoantibody screen are negative. Plain X-rays of affected joints may reveal typical radiographic features including soft-tissue swelling, bone proliferation at the base of digital phalanges coupled with resorption of the distal tufts (the ‘pencil-in-cup’ deformity) and fluffy periostitis [31]. Chest radiographs are useful as a baseline when clinical examination suggests cardiac or pulmonary involvement.

Emergency management

Emergency treatment involves the relief of pain and reduction of joint inflammation, with appropriate specialist follow up. Education, rest and exercise and referral to a multidisciplinary allied health team are the mainstay of ongoing management. Admit patients if their symptoms are severe enough to preclude oral therapy or safe discharge pending outpatient specialist follow up.

NSAIDs are useful for acute symptomatic relief and intra- or peri-articular corticosteroids may be used for short-term relief of painful arthritis or enthesitis. Long-term therapy with disease modifying agents, such as sulphasalazine or methotrexate, is instituted at specialist review [32]. Oral corticosteroids are usually avoided as their cessation often exacerbates the psoriasis. Therapy with tumour necrosis factor-α antagonists, such as infliximab, etanercept and adalimumab, has been approved for rheumatologists under strict access criteria for severe disease resistant to other DMARD therapy.

Emergency management of skin disease includes topical treatments, such as emollients and keratolytic agents [33]. Phototherapy and photo-chemotherapy may be instituted on early dermatological consultation.

Prognosis

Psoriatic arthritis generally runs a more benign course than RA but, nonetheless, patients suffer from considerable morbidity. Adverse prognostic factors include onset before 20 years of age, erosive disease and extensive skin involvement [30].

Reactive arthritis

Reactive arthritis is an aseptic peripheral arthritis following certain infections, which include bacterial infections of the urogenital tract usually by Chlamydia trachomatis, or of the gastrointestinal tract with organisms, such as Shigella, Salmonella and Campylobacter. It may also follow viral infections, such as HIV, although in the case of HIV, co-infection with sexually transmitted organisms rather than the virus itself is thought to be the cause [34]. The seroconversion illness of HIV has its own constellation of articular symptoms and is considered to be a separate entity.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of reactive arthritis is difficult to define owing to diagnostic uncertainty particularly in the setting of asymptomatic sexually transmitted infection. The male preponderance is up to 9:1 following sexually transmitted infection, but males and females are equally affected following gastrointestinal tract infection [35]. The peak incidence is around age 35 years and up to 75% of patients are HLA-B27 positive [35]. An important exception is with the reactive peripheral arthritis that occurs in 20% of patients with idiopathic IBD, a condition that may mimic gastrointestinal tract infection, but where patients are usually HLA-B27 negative.

Clinical features and diagnosis

The diagnosis of reactive arthritis is clinical. It typically manifests within a month of gastrointestinal or genitourinary infection, although the latter is frequently asymptomatic [36]. Musculoskeletal manifestations include myalgias and asymmetric polyarthritis affecting the knees, ankles and small joints of the feet in particular, although peripheral upper limb involvement is seen. Affected joints demonstrate marked inflammatory features with erythema, swelling, warmth and exquisite pain on active or passive movement. Fever and malaise are common.

Arthritis and extra-articular manifestations

Symptomatic spondylitis and sacroiliitis cause low back and buttock pain and occur frequently. Dactylitis and enthesitis are characteristic features of this disease with heel pain from plantar fasciitis or Achilles tendonitis [36].

Extra-articular features associated with reactive arthritis include keratoderma blennorrhagica, the scattered, thickened, hyperkeratotic skin lesions with pustules and crusts seen in Reiter’s syndrome and circinate balanitis. Keratoderma blennorhagica on the soles or palms may coalesce to form plaques virtually indistinguishable from those of psoriasis [37]. Circinate balanitis causes shallow meatal ulcers that are moist in uncircumcised men or hyperkeratotic and plaque-like in circumcised men [37]. An inflammatory aortitis occurs in 1% of patients and may result in aortic valvular incompetence and/or heart block

The peripheral arthritis associated with IBD is migratory and occurs in a similar distribution. Common features include large joint effusions, particularly involving the knee, and sacroiliitis or spondylitis [38]. Unlike peripheral arthritis following genitourinary infection, the spondylitis of IBD-associated arthritis does not tend to settle with treatment of the bowel inflammation. Cutaneous features associated with this form of arthritis occur mainly on the lower limbs and include erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum [38].

Investigations

Laboratory

An active inflammatory response is seen in the acute phase with a neutrophil leucocytosis and thrombocytosis and raised ESR and CRP. The presence of a mild normochromic, normocytic anaemia suggests chronic disease. Send blood for HLA-B27.

Document the preceding gastrointestinal or genitourinary organism by stool culture or cervical/urethral swabs [39]. Rheumatoid factor and ANA are negative.

Joint aspiration